1. Introduction

In 1962, the Swedish author Jan Myrdal lived for one month in the village Liulin in China’s Shaanxi province and interviewed peasants about their experiences of land collectivization and village life. Three years later the book “Report from a Chinese Village” was published in English [

1] and became a unique account from the transformation of a, at that time, very closed country. With a case study of one single village, Myrdal was able to show the transformation of rural China after the communist takeover of 1949. Today, almost sixty years later, the conditions in rural China are very different. This paper uses the same method as Myrdal, a single case study, to report about the transformation of a Chinese village in a new time.

Rural population shares are declining across the world and calls for rural vitalization have been raised [

2]. Urbanization is a global trend but national governments’ measures for rural areas vary and so do their abilities to act. This study focuses on China, the country with probably the strongest government in the world, making the experiences hard to transfer to other countries. However, how the most populous country in the world transforms its countryside is a process of global interest.

The economic reforms that were implemented in China from 1978 onwards have had an enormous influence on China’s economic growth and the inhabitants’ living standards. However, they have also contributed to increased urban–rural inequalities in wages and living standards. Hundreds of millions of people have moved from the countryside to cities and the human resources of the countryside have been weakened. Therefore, when the central government now lays strong emphasis on rural vitalization, it is necessary to initiate a general discussion on what is needed for rural revitalization at the basic level, the village.

With the economic transition and changes in urban–rural relationships, rural revitalization has become a great political concern for the Chinese central government. Rural revitalization mainly aims at increased production, rural development, higher standards of living, clean and tidy villages, and effective governance. However, how this is being implemented at the village level is so far insufficiently analyzed.

Some authors consider that a reform of the land system (land institutions and policy) is a significant prerequisite for rural revitalization to take place [

3,

4]. Rural land in China is often classified into three types: agricultural land, collective construction land, and unutilized land. Rural collective construction land can further be divided into commercial land, rural homesteads, and public land. The rural homesteads account for the largest share of rural collective construction land. With increasing living standards, many farmers have built new houses and many households have come to possess two or even three homesteads since they have not torn down the old vacant ones. The result has been a low utilization rate of the rural land areas and even the phenomenon of “hollowing villages” (villages with a majority of abandoned houses and homesteads). Important reasons for this have been a lack of a functioning market for homestead transfer and a lack of flexible and effective policy support [

5]. In 2015, the central government put forward the homestead system reform, which aims at developing the utilization efficiency and increase the households’ property income. Different models of homestead transfer have been tested in various regions. The question of how to activate and make use of homestead transfers in order to provide support for rural revitalization is both an important political concern and the focus of this paper.

Previous research has focused on the necessity of homestead withdrawal, the influencing factors of withdrawing, the withdrawal mechanisms and the compensation for withdrawal. Regarding the necessity of homestead withdrawal, some scholars consider the rural homestead to be a kind of social welfare good or social security product, which was distributed for free to farmers as a place of residence under the arrangements of collective ownership of properties in the planned economy [

6,

7,

8]. However, with the increasing degree of urban real estate marketization, the continued non-capitalization and non-commercialization of rural homesteads will damage the “property rights” of farmers and obstruct the realization of capitalization of farmers’ homesteads [

6,

9,

10]. Regarding the influencing factors of homestead withdrawing, previous research has identified a number of significant factors: the distance between the homestead and the city; the number of persons permanently living in the household; if the household has any children working in the city; whether the real estate property has been titled or not, and the legal status of the inheritance and mortgage rights [

8,

11,

12]. As for the homestead withdrawal mechanism, different modes have been developed across China. Examples are the “land ticket transaction” in Chongqing; the “homestead replacement for housing” in Tianjin; the “two separate, two replacements” in Jiaxing, Zhejiang province; the “land comprehensive consolidation as well as the homestead purchase and reservation” in Chengdu, Sichuan province; and so on. All these modes have brought about certain benefits in terms of increased land supply and the (financial) improvements of farmers’ life [

10,

13,

14]. They have promoted the improvement of the efficiency of rural land resource allocation and brought about improvements in farmers’ income and welfare in the short run. However, they have also weakened the farmers’ land rights and interests to a certain extent, resulting in unsustainable livelihoods for the farmers due to loss of their employment and/or revenues from the land.

It has been argued that the value of the functions of social security and unemployment insurance of the homestead is much higher than the actual compensation for withdrawal [

11,

12,

15]. Consequently, the government should pay attention to the social security and insurance function of homesteads, in order to ensure that the living standard of households does not deteriorate after the homestead withdrawal [

8,

16]. There is also research concerned with the impacts of farmland transfer on households’ income and welfare [

17,

18]. Zhang and Feng investigated the impact of farmland transfers on the households’ income using household data from the Jiangsu province [

18]. You and Wu analyzed farmland transfers, off-farm employment and farmers’ welfare, using a structural equations model to test the relationship between these three aspects [

19]. Liu analyzed the impact of farmland transfer on the households’ income and found four different mechanisms that have influenced increases of farmers’ income [

16]. Shanguan et al. investigated the impact of different models of homestead replacement on the farmers’ welfare by using household data from three different areas and found that the influences of each model with respect to farmers’ well-being (family’s financial situation, living conditions, social security status, social capital status, farmers’ satisfaction) were different [

20].

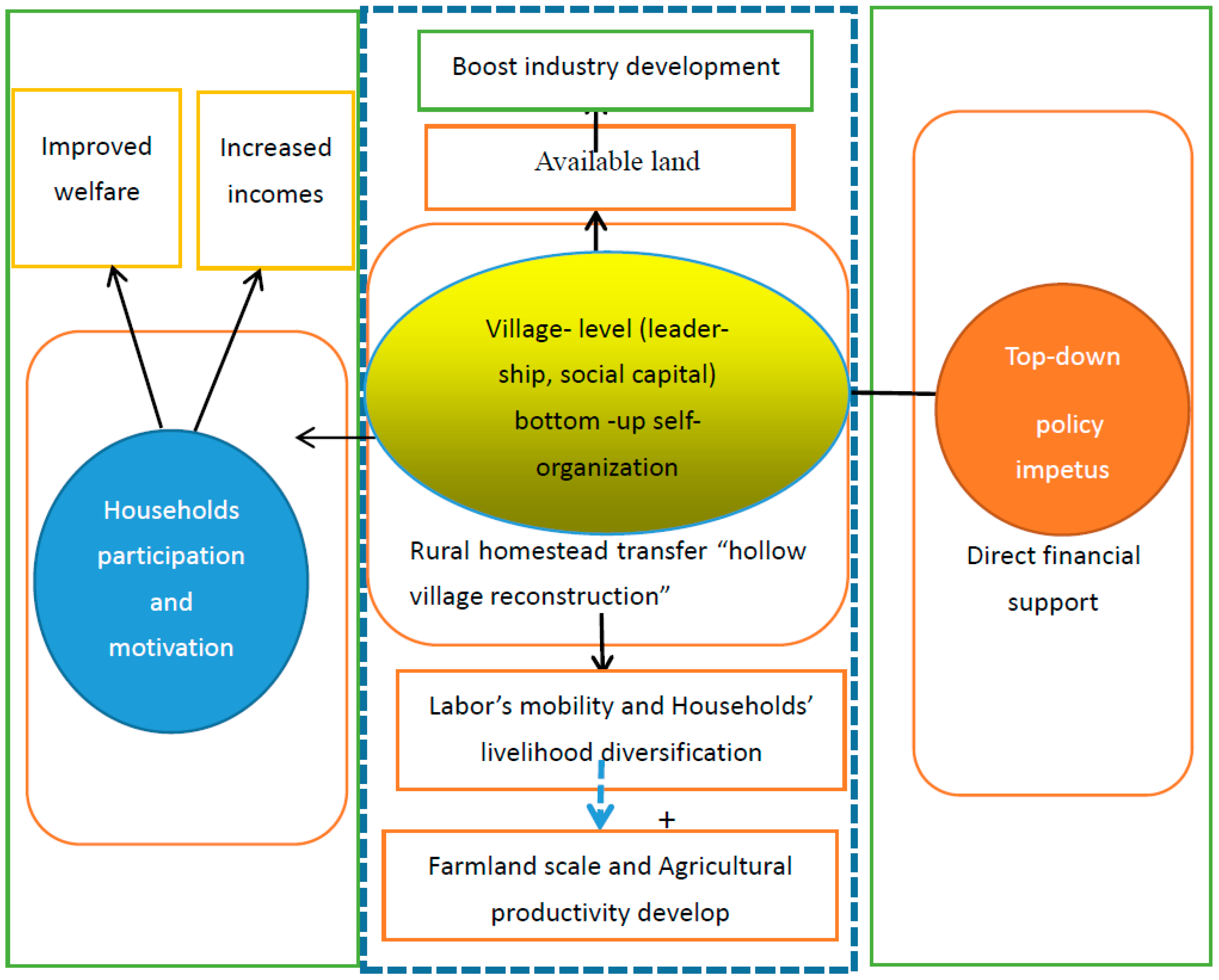

Another aspect highlighted in the literature is the role of government in rural revitalization [

21,

22]. Also, the combination of bottom-up initiatives, participation in the rural reforming practices, and the top-down policies have shown to be important in rural economic development and poverty reduction [

9,

22,

23,

24,

25]. However, the role of independent initiatives and leadership at the local level are, with few exceptions [

26], not noticed in the Chinese rural development literature.

Previous studies have mainly focused on the various models and the performances of homestead transfers, the distribution of value-added income from homestead transfer and the impact of homestead transfer on the welfare of farmers [

4,

14,

17,

20,

22,

27,

28]. However, the effect of homestead transfer on rural revitalization remains an unsolved issue. This article aims at analyzing the effects of one of the tested homestead transfer models on rural revitalization, by empirically studying the role of the village collective and local leadership in the process of homestead transfer. We raise two research questions:

In which ways does the rural homestead transfer promote rural revitalization? What is the role of the village leadership and the village collective in the process of rural vitalization? The insights obtained from this article can provide an input to the design of appropriate policies to improve the functioning of rural homestead transfer. This connects to the national government’s goal to achieve rural vitalization, but also to local governments’ role in creating institutional space for establishment of new industries.

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides a theoretical basis and analysis framework for the role of homestead transfer in rural revitalization.

Section 3 gives a brief description of the study method, data source, and study area, as well as the results of the empirical analysis of homestead transfer and rural revitalization. The discussion is presented in

Section 4.

Section 5, finally, presents conclusions, policy implications and possible further research.

3. The “Hollow Village Reconstruction” of Wantang: Empirical Case Analysis

3.1. Case and Research Area Overview

In January 2015, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the State Council enacted “the opinions of rural land acquisition, the collective commercial construction land shall be put into the market and the homestead system reform”, which was passed by the Central Leading Group for Comprehensively Continuing Reform. Specific to the homestead system reform, three significant pilot contents have been proposed: (1) to explore the different kinds of forms of residence for all the households, (2) to establish various mechanisms of paid use and paid quitting, (3) to attempt the mortgage route of homestead property rights. Yiwu was chosen as a pilot county, and different kinds of homestead transfer models has been tested, the Wantang village in Chi’an town is a typical pilot.

Following the discussion above, we have chosen a case of a village development. The village has some advantaged endowments of resources and has certain market connections with urban areas. First, it is a new homestead transfer model practice that previous literature have rarely mentioned before. Second, the village analyzed here is neither a village in a remote mountain area nor a village in the suburbs of the city. It is a Chinese countryside village in a general sense with certain access to transportation networks and maintains a certain relationship and also market connections with urban areas.

In China, public administration take place at six levels: nation, province, city, county, town, and village. In 2015, the Chinese central government selected 15 counties as the homestead system reform pilots, and Yiwu County was one of them. Taking advantage of the opportunity, Yiwu has tested different models. Wantang is one of the pilots of “hollow village reconstruction”, and have attracted much attention. Because of possessing the potential to develop tourism, it has attracted a large number of tourists to come and visit the tourist attractions of the village, which include fruit and berry picking gardens and leisure gardens.

Chi’an town is located in the south of Yiwu, Zhejiang province. The land use structure is sixty percent mountains, five percent water, thirty percent farmland, and five percent transportation and residential sites. Chi’an town has a long history and the cultural landscape and tourism resources are considered rich. Chi’an town’s development strategy is “strong towns for cultural, ecological and leisure tourism”. This means paying close attention to project construction and effective investment, expanding the space for economic development, promoting the construction of beautiful countryside, and improving the social management mechanism. The total number of census-registered households of the town was 35,022 in 2017 [

51].

Wantang village is a part of Chi’an town, located in the south-west of Yiwu and close to the Five Finger Mountain scenic area. Surrounded by mountains and beautiful scenery, it is a popular leisure tourism area for urban residents. Wantang is located 18 km from Yiwu city and 132 km from Hangzhou city (as presented in

Figure 2). There are 196 households in the village, 405 inhabitants in total. Since 2012, it has carried out the assignment of “hollow village construction”. It has torn down more than 80 units of derelict houses, corresponding to 7720 m

2. In January 2013, the enforcement regulation of “hollow village reconstruction” of Wantang was approved by Chi’an people’s government and agreed for implementation. It has accomplished the assignment of homestead distribution and approval, which involved the first batch of 37 households and then a second batch. By the end of 2019, nearly all of these households had accomplished building new homes, the remaining small number of houses are under construction.

3.2. Research Methods and Data Source

This article uses the case study method. We have adopted the “purpose sampling” strategy in non-probability sampling. The advantage of a case study is that it can give detailed information and if it investigates a general process, it can contribute to illuminating general features of this process. However, as local conditions, access to markets, etc., vary very much in China, we cannot expect that all the conclusions drawn from a single case study are valid for all Chinese villages. Wantang is a village at the urban-rural fringe and this is a position it shares with thousands of villages in China. As shown above, Wantang is a small village and this means that the results of rural homestead transfer are small in absolute numbers, but if similar results were achieved in thousands of similar villages, it would mean a great change.

Numbers, areas and investments of “hollow village reconstruction”, as well as the land use structure were collected from the official statistics of the Wantang village committee. Benefits and incomes of “hollow village reconstruction”, the various data on the income and welfare status of the farmers, before and after the homestead transfer were analyzed based on questionnaire surveys and face-to-face interviews. “Green farming Wantang” Co., Ltd. were interviewed to explain how households’ activities and livelihood changes as a result of the modern scale agriculture and agricultural tourism industry development under the innovated land policy in Wantang village. The main author visited the village twice, in January 2018 and July 2019 and performed semi-structured interviews with several types of actors: (1) The director of the village collective, who has participated in the introduction of the enterprise, and was responsible for the entire process of homestead transfer in the village. (2) A retired village accountant that has full information on the village’s economy, population, and other conditions. (3) A woman being employed by the enterprise, and who has a clear picture of the employment conditions in the village. The reasons for choosing these interviewees are that they are all very familiar with the project of homestead transfer in the village, and they have participated in the project personally.

The director of Wantang village, Mr. Zhu, has ten years of experience in living and working in Hangzhou, the capital city of Zhejiang before he came back to the village. He is an example of a returning migrant although he functions more like a village elite. The woman being employed by the enterprise is a typical representative of a returning local employee. The retired accountant possesses a lot of information on the village, including the situation of the households who oppose homestead transfer (none of the households that opposed homestead transfer wanted to be interviewed).

After a long experience in the big city, Mr. Zhu had accumulated a great deal of financial capital and knowledge about how the market economy works. He had also built up an extensive amount of social capital, not only in the village but also outside it, therefore all the villagers elected him as director unanimously. The interview with Mr. Zhu included the fundamental situation of the village, the resource conditions of the village, the project of “hollow village reconstruction”, the new enterprise and its operations, the change in the households’ living conditions, and the village collective’s efforts in the “hollow village reconstruction”. Mr. Zhu provided the researchers with all the quantitative figures on the village’s development being used in this paper. In addition, we have also interviewed Manager He of the village enterprise, the secretary of the village, the administrator of the cultural hall, and three households (F1, F2, and M3).F1 is an old lady employed in the public dining room of the village, F2 is a young women who works as the office assistant of the village collective, M3 is an old farmer who is familiar with the conditions of the village and who has held the post of accountant in the village for several years. The interviews were performed in the office building of the village committee and in the households’ houses. The contents mainly focused on the reconstruction condition of their homestead, the user conditions of their homestead, their living and production situation, the households’ labors employment condition, and the change in their income and well-being. We also asked about the subjective feelings about the environment and the status of democratic participation). The author has also made a detailed collected policy documents and announcements from the town and county government.

3.3. Results

3.3.1. Agricultural Production and Income Increase

Before the “hollow village reconstruction”, the cultivated land area was 11.47 ha. The main planting varieties were peach, pear, watermelon, etc. The agribusiness entities were small household farmers only. After the “hollow village reconstruction”, the cultivated land area increased by 16.2% to 13.33 ha, and the plant varieties became more abundant. Now, the main agribusiness entities are the agricultural company and farmer cooperatives. The proportion of small household farmers is now only 15% and the share of cultivated land transferred is 85% (as shown in

Table 1). The farmland transfer price is 400–500 yuan/mu/year (1 mu = 0.067 ha). Furthermore, the household can not only obtain the land rentals, but also capture the collective share dividend from the village according to the principle of equal distribution.

3.3.2. Densification of Housing, Land Use Intensification and Availability for New Industries

Before the renovation, the village was in a state of decay. Several homesteads were idle, abandoned and disorganized, multiple houses were owned by one household. Some households built the new house without tearing down the old. Hence, some of the old houses were not used in the old village. Land use efficiency in the village was low, the infrastructure facilities were very run down, and the land use layout was extremely sprawled (as showed in

Figure 3).

From the pictures of the hollow village before and after renovation, we can easily see that it has taken on a completely new appearance. After the renovation, the houses are uniform, well-located, with good infrastructure. Land use is more efficient, and the land use structure is more reasonable. A newly designed countryside (as shown in

Figure 4).

Through the “hollow village reconstruction”, the farmers have moved to a concentrated community with the form of independent houses. Most of them have moved into the centralized, re-planned areas, which has promoted a more intensive use of land. Before the “hollow village reconstruction”, the locals described the village as “yi qu er san li, yantu si wu jia”, which means “quite disordered and messy”. Now all members of the village collective have obtained their newly distributed homestead in the centralized planning area (as seen in

Table 2). Therefore, a large area of collective construction land has been saved. Taking advantage of this, the village committee has set up a variety of public facilities, including an office building, a sports field and a variety of cultural and entertainment facilities, including a big cultural hall. They hired an architect to work out the design of a combination of places for performances, reading, classrooms and other use venues (the details can be seen in

Table 3). As soon as this was finished, it started attracting a large number of tourists. The entertainment space for the households is much bigger compared to before. The whole village is can be accessed by broadened concrete roads, and the water and electricity facilities have been improved. Consequently, the life of households in the village is much more convenient and comfortable than before.

3.3.3. Promotion of the Agglomeration of Housing and Industry

The densification of housing gave access to previously idle homestead resources, made the land more intensively used, provided land for the industries, as well as the construction of public office building and facilities. The village re-planning and intensification of land-use, which saved a certain amount of land space, made it possible for the “Green farming of Wantang development and construction company Ltd.” to settle in the village and form an industrial park. The enterprise was introduced by the town government, who is in charge of attracting businesses and firms, and negotiates terms with them. Specifically, it is the agriculture department of the town government who is responsible for the negotiation, but the contents of the contract are discussed between the firm and the village collective. After approval during a meeting of the village collective, the contract with the enterprise was signed. The firm running the agricultural business, which include the cultivation of different kinds of fruit, it also running the processing industry for the agricultural products. It has a registered capital of 5.68 million RMB (the details can be seen in

Table 4). The village collective owns 10% of the shares, the individual villagers are not shareholders, but they obtain income distributed by the village collective.

The village collective dismantled the idle and abandoned houses, organized the construction of modern buildings, which are all three and a half floors high. Taking advantage of the modern style and well-planned houses, the two upper stories are planned to be used as guest rooms for tourists. The stories below are used as farmhouses and for catering services. The operation of guest rooms and farmhouses are determined by the surrounding environment, in this case the tourism and cultural resources. In this respect the Wantang village happens to possess advantageous resource endowments. Therefore, the households are willing to participate in the operation of farmhouse and guest rooms without protests. There are also limited amounts of saved construction land that the village collective has transferred to the “Green farming of Wantang”, where it is planned to build a “holiday village”.

The enterprise, the village collective, and the households have different responsibilities in the industrial management. The enterprise takes care of brand building and attracting visitors, the village collective is responsible for arranging and supplying different kinds of facilities, while the farmers are in charge of providing catering and accommodation services. Taking advantage of the transferred farmland from the households, the enterprise uses it for the construction of business and leisure facilities. It has formed a large ecologic industry garden, containing plantations, picking gardens, ecologic gardens, and tourist leisure gardens. The water reservoir is used by the tourists for fishing. The village collective charge rent from the enterprise and the benefits are distributed between the village collective and the enterprise in accordance with the shareholdings. With the office building and the cultural hall as the carrier of tourism, the village has also been equipped with cultural facilities and a small library, which are amenities attractive for tourists.

3.3.4. Promotion of the Resource Diversification of Labor

Based on the collective land, which has been transferred for the construction of the ecologic industrial garden, the farmers in the village have a priority to benefit from the garden. Under the basis of equal wage and treatments, employment priorities are given to the local farmers. The old farmers who have stayed in the village, who gradually lose the ability to work and are unable to perform the hard work in the city, can work with some simpler tasks connected to the picking and planting in the gardens of the enterprise like weeding, cleaning, and other tasks. This kind of work is mostly performed by farmers in their 60s and 70s.

Because of the construction of the ecologic garden (which contains a leisure park, a medium-sized farm, and guest rooms) which will be built soon, some of the farmers will have easy access to local off-farm employment, in addition to running their own farmland (as we can see in

Table 5). Normally, the founding of industries go hand in hand with the resettlement housing for farmers. This vastly reduces the commuting costs, search costs, costs associated with risk, and housing cost. Because of the establishment of the industry, which have increased the local wage level and provided a great deal of off-farm work opportunities for the local people, some farmers even come back to the village and proceed to engaging in local off-farm work in the industries [

9,

16,

18,

19]. They earn wages from the enterprise that are not much lower than those in the city. According to the information we have received, it has provided employment for 20–30 farmers in the village. With the development of the industry, it will absorb more local labor. Furthermore, the number of returning farmers will reach up to 20–30 people (as shown in

Table 6). Hence, the “hollow village reconstruction” has restructured the villager’s livelihood strategies.

Thanks to the new, secure tenure, the households do no need to worry about their homestead and the farmers can rent out or sell (this is comparatively scarce) their homestead and house, which has brought about great benefits from the property. This has helped the farmers to accumulate capital and enhanced the ability to move to town. It has promoted the migration of farmers to off-farm employment in the urban areas and indirectly increased the farmers’ incomes. While the remittances from out-migrant labor may have a slightly positive effect on the revitalization of local villages, as well as the market connections, the knowledge structure and innovation capacity, which they may bring through a round-trip migration, is more important.

Through the “hollow village reconstruction”, the farmers in Wantang have realized a labor resource diversification. This entails three different types of employment: local off-farm employment, out-going migration and return migration for off-farm employment, all of which have increased the farmers’ income.

3.3.5. Financial and Social Capital Assisting Low-Level Urbanization

Capital for the Reconstruction

Yiwu city government permitted that a part of previous wasteland (slopes and private plots) could be transformed into homesteads that were distributed to the households. In the “hollow village reconstruction”, if the household choose to quit their homestead in exchange for money, they can obtain a standard compensation by 1500 Yuan per m2, which includes previous surplus homestead and also a reimbursement for the right to receive a new homestead. However, the households who quit for monetary compensation will no longer enjoy the right of homestead distribution. After accepting monetary compensation, the homestead will be controlled by the village committee. The households that withdraw will accumulate their property income, those who do not ask for the monetary compensation will be compensated by a new homestead in the new re-planned area (1–2 persons are compensated by 108 m2, 3–4 persons by 126 m2, above 5 are compensated by 126 m2). All the new redistributed homesteads have been formally titled. The new houses are built by the households themselves. They have to calculate the benefits and costs for the demolition and new construction.

The newly distributed homesteads have all been issued certificates of use, this increase the households’ expectation of security. They can enjoy the rights for usufruct of the homestead and promote the transfer of houses.

The external policy support from the government has also facilitated the “hollow village reconstruction”. First, the county government has provided 3 million Yuan as incentive payments to encourage the village collective to demolish abandoned houses. Secondly, the village collective has also transformed the slopes and hillside fields into terraced fields, which has given 1.3 million Yuan in reward from the county government.

The village committee has made great efforts to generate revenues for the village. The village collective has introduced the enterprise, in which the village collective own 10% of the stocks. The saved construction land has also been utilized for public office building. The village collective rents out the upper stories of them, mainly for migrants from the outside who are working in the surroundings.

The households were charged fees for site selection. After that, the village was re-planned, the households choose the sites and rebuild their houses. The charged fees varied depending on the location of the homestead; the total revenues reached nearly 1.5 million Yuan.

Finally, the enterprise creates rental incomes for the village collective, with nearly 289,000 yuan per year.

Leadership and Social Capital

As mentioned, the director of the village has returned from a long period in the cities of Yiwu and Hangzhou. With his return, he brought a large network of social and business relationships, which has been used in the transformation of the village. Moreover, his leadership has brought knowledge about market thinking and contractual relationships between businesses and the village. This have showed two things: on the one hand, the market sense, knowledge, and capacity for innovation that has been accumulated during the period outside in the big cities, promote the market linkages with companies/enterprises and the connections with local government represents a significant amount of external social capital for the village. On the other hand, the entrepreneurship and the leadership established by the traditional social connections among the villagers through the long-term village experience accumulation, represent the significant amount of internal social capital in the village. The village cooperative coordinates mass work, dealing with the relationship between enterprise and farmers and implement the dividend promised by enterprise to farmers, as well as arrange and ensure that the benefits and dividends are distributed fairly and equitably among the households. This solid social capital reduces transaction cost between the enterprise and households, the village collective and the households, and facilitates collective action at the village level. Thus, the village director has contributed to an extended external/bridging social capital for the village, concerning both networks, norms and values.

The internal/bonding social capital of the village is based on strong traditional social ties. According to our field investigation, the village has clear rules and regulations that are posted on the notice board. The villagers have long-lasting relationships and can cooperate mutually even if not all homesteads have taken part in the homestead transfer. (Persons who have moved to the city and are waiting for a higher bid on their homestead rights hold several of the homesteads that have not participated in the transfer process). Owing to the cultural heritage of a brown sugar mill, which has become the common cultural heritage of the villagers, as the local villages said “brown sugar is a childhood memory and symbol of the hard work of our ancestors”. It has acted as the traditional blood and the crystallization of the collective labor of ancestors; the village members express great trust and networking. These features did not only help the village director to implement the homestead transfer quite smoothly but also to promote the successful introduction of the enterprise.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Achievement of Overall Revenue Growth

Rural revitalization may be difficult without support from the government. The Government can provide support through direct financial payments and by indirect subsidies. They can also create incentives to stimulate intensive land-use and innovation in the villages. The village collective can also raise some funds on their own. Lease of collective construction land and unified transfers of agricultural land can create a collective operating income. Village collectives can also be the main actor in joint investments, such as the construction of collective public rental housing and factory buildings for rental and transfer. The households, having institutionalized usufruct, can choose to rent out their house, or even transfer their homestead and house properties, which can accumulate property income.

The second significant component of rural revitalization is the intensification of land use and the agglomeration of industries. By effectively activating the redundant homestead resources, land space for new enterprises and developers is released. The original homestead resource can become the home for industrial park construction and a small industrial agglomeration. If this happens, it will give the farmers higher payed local off-farm employment.

A possible third component of rural revitalization is labor’s resource diversification. Through the homestead transfer, farmers can rent out or sell their right to idle houses and homestead and realize the value of the land resource. This has increased households’ capital accumulation, strengthened their transfer ability and enhanced the confidence of transformation. It has promoted the migration of rural labor, helped the farmers move to the city and replaced low-productive farm work with higher productive work [

18,

19]. This has increased the households’ incomes and welfare. The average income in the village was almost 96,000 Yuan before the homestead transfer in 2014 and this came almost solely from the off-farm income. In 2018, the average income of the households had increased to 125,174 Yuan. (From our field investigation, the average agricultural income of the households in 2018 was 870 Yuan, while the average non-farm incomes of the households was 124,334 Yuan, coming from a variety of sources, the data comes from the researcher’s field work and interviews with the local farmers, and through the questionnaire sorting and statistics). The income sources are diverse: the land transfer rentals, urban employment and local off-farm employment wage income, the collective benefits distribution, and even small amounts of agricultural operating income. The percentage of income from urban jobs occupied about 50%, which is a lower share than before. The increase comes from a wide range of sources: the agricultural operating income, the rental income from the farmland transfer, the rental and transfer income of the house, and the collective profits distribution. Also, wage income from those who commute and work in the cities but live in the village contribute to the increase. Regarding those who have moved to the cities, they contribute to rural revitalization if they bring back remittances to their families in the village. All in all (1) higher productivity in agriculture; (2) housing densification and land intensification; (3) land available for industry agglomeration in the local area; (4) labors’ multiple paths of migration and livelihood diversification; and (5) the bridging external social capital and bonding internal social capital–these five factors coupled together and mutually cooperating are the keys to rural revitalization.

An important question is to what extent the income of this village comes from the city before and after the proposed initiative. Before the RHT, the only urban contribution was the wage income earned by farmers from non-agricultural employment in cities. After the RHT, the enterprise was established, which promoted the employment of local farmers and brought wage income. The industry park and public facilities have also attracted urban tourists, which have been the source for new incomes. The financial subsidies from the city government also directly promoted the process of village reconstruction and the development of the local economy. Hence, the importance of urban areas for the village’s development is undisputed.

The different stakeholders may take their respective initiatives in the process of rural homestead transfer. The local government provides financial support for industry and project introduction and acts as the role of server. The village collective is responsible for the mobilization, the bonding social capital to advocate the households to participate in the homestead transfer, as well as the mediation of the issues between the enterprises and the households. The households collaborate, take part in the homestead transfer and the construction of the new, “urban” village. We also find that the bottom-up initiatives from the village collective and the leadership presented by the village cadres have played a significant function in the rural revitalization. The village collective’s market insights, mobilization ability, negotiation with the enterprise and services for the households, as well as the organization of income distribution have made great contributions to rural vitalization.

To summarize, we can answer the research questions in the following way:

The rural homestead transfer has promoted rural revitalization by farmers’ capitalizing on the homesteads, densification of housing to free land for industries and local public and commercial services, and by the households’ livelihood diversification.

The village leadership has through its social networks and trustworthiness (i.e., its social capital) acted as the central node that has linked the households and the village collective with the enterprise and external capital and officials. The village leadership has succeeded in mobilizing, organizing and coordinating the external and internal actors. This has smoothed the process of RHT, the establishment of the enterprise and the premises for public services, raised and diversified the farmers’ incomes and thereby promoted the rural revitalization.

4.2. Remaining Problems of the “Hollow Village Reconstruction”

In the process of “hollow village reconstruction”, the emotional factors associated with the ancestral houses must not be neglected. There are still 5–10% of the households that have not participated in the “hollow village reconstruction”. There are two main reasons to this: (1) Some of the households who has moved and bought houses in Yiwu city, lack money to build new houses in the village, but they have a strong sentiment for the property, which is called “locking the bamboo”. (2) There are also households who are “insured, closed, and old-fashioned”, and not willing to participate in the “hollow village reconstruction”. Therefore, the village collective has not been able to mobilize them, and they did not want to be interviewed for this study. The opinion of those that we interviewed was that these people had been left behind when their relatives moved and settled in the city, and that these people were introvert, isolated, and not willing to communicate with their neighbors and other villagers. This complicated situation makes them unable to achieve any change of their current status. There are reasons to believe that these farmers may have to consider the change of benefits and costs as well as the loss of functions and utility due to the homestead transfer. They may not be able to bear the various consequences of the homestead transfer that may bring about changes on their livelihoods. Homestead transfer should take full consideration of the willingness of farmers. Land is the root of farmers’ survival and development. The success of any homestead transfer program, therefore, depends on how well farmers’ needs, capabilities and aspirations are reconciled and integrated into it [

50]. Only when the rights and interests of farmers, as well as the mental and emotional respect of farmers are not impaired, farmers can maximize their enthusiasm and participate in “hollow village reconstruction”. Therefore, in the process of “hollow village reconstruction”, the specific care and key assistance for the actual situation of some farmers is necessary.

The procedures of the “hollow village reconstruction” are quite complex regarding organization and management. They include negotiations and transactions between the village collective and the households, and the village collective and the enterprise. To introduce a market system in the process of “hollow village reconstruction” involves the disintegration of the whole process: the investigation of existing resources, the village planning, negotiation with the households and the enterprise, signing the agreements, contribution of capital, land transfer, making compensations, income distributions, employment arrangements, supervision, and so on [

52]. In the process of the “hollow village reconstruction” in Wantang, the households were not clear over what kind of operating strength and business philosophy of enterprise they were going to transfer, there was no public bidding process or any competition mechanism. A strict contract form and market approach could have given other results and reduced possible frictions and problems and enhanced the efficiency of the resource allocation.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

The case study of Wantang village in Chi’an Town verified and answered the two questions that were raised in this paper. The homestead transfer has realized an overall rural revitalization, through a capitalization effect on homestead values, a densification effect of housing, and a diversification effect of labor resources.

A general conclusion is that both external, top-down policy support and endogenous bottom-up initiatives has been decisive in achieving rural revitalization. The homestead transfer has played the role of utilized carrier, which has integrated the different parts and aspects in the process of rural revitalization.

In the concrete process of homestead transfer, the village collective has represented the endogenous driving force for rural revitalization. Our findings emphasize the need for bottom-up initiatives from the village collective, which, through an image of credibility advocated the households to participate in the “hollow village reconstruction”, established various channels to solve the funding of the reconstruction, introduced an enterprise and an industrial park, developed the collective economy, and helped arranging the farmers’ employment. The leadership demonstrated by the local village collective’s self-organized actions played an important role in carrying out revitalization initiatives [

26,

37]. It indicated that the quality, leadership, and entrepreneurship of the village cadres gave play to significant impacts of the homestead transfer [

21]. However, although the homestead transfer in Wantang has achieved a “low-level rural revitalization”, some critical perspectives still need to be considered. The farmers’ demands and expectations in the transfer of homesteads may be heterogeneous. In addition to the basic monetary and housing demands, it is still necessary to take into consideration the emotional and psychological needs of farmers.

Therefore, in order to achieve rural vitalization at the village level, a number of issues must be dealt with: capitalization of homesteads, densification of housing and releasing of land, establishing of industry, and intensification of labor diversification.

Based on the case study the following implications for policy can be drawn:

First, the building of industry together with the local resource endowments is the key factor for the village’s revitalization. It does not only develop the efficient use of land resources but also creates off-farm employment for the local farmers. In the process of homestead transfer, the saved construction land space provided for the industries should be emphasized.

Second, the households’ positive participation is an important prerequisite for the success of the homestead system reform. This can be achieved by strengthening farmers’ rights of participation, awareness and decision-making, and by improving the public participation mechanism, reducing the information asymmetry, and avoiding redundant transaction costs.

Third, it is necessary to strengthen the ability and quality of local leadership (village cadres), to promote the return of successful migrants and young workers and promote them to play leading roles in rural revitalization. The powerful internal social capital from the traditional social ties combined with the external social capital from modern entrepreneurship need to be emphasized and fostered. This will promote effective collective action at the village level, and act as bridge and linkage between enterprises and the households, which is especially indispensable in the process of rural revitalization. To combine rural governance and co-governance, with bottom up and top-down initiatives seems to be an effective method.

Fourth, the rural revitalization also needs external policy support. A service-oriented county government that provides public policies and products is particularly critical in the homestead transfer. It should also play a leading role in planning, organizing, promoting, integrating resources, providing services, and strengthening management in the reform of the homestead system, to handle possible frictions and obstacles.

In this paper, we have examined how a village takes action to realize rural revitalization through the capitalization of homestead value, the densification of housing, and the diversification of labor. We found among other things that the village collective plays an indispensable role in the process of “hollow village reconstruction”. External policy and internal endogenous forces are important in the rural revitalization. These are necessary conditions for the development of all varieties of villages. However, this is a case study, and the role of amenities and the fortune of the homestead indicators cannot simply be copied to other villages. In particular, villages in remote rural areas and villages with poor geographic location conditions might lack the necessary resource endowments and access to markets and may therefore not achieve rural revitalization in this way. China is a large country with many different types of rural areas and a one-size-fit-all policy for rural revitalization is not possible. However, thousands of villages in the urban-rural fringe areas can realize the development and revival of the village economy in a similar way to Wantang because of their geographical conditions and resource endowments. How village collective, government, rural resource endowments, and social capital combine and incorporate well to reach rural revitalization is still an issue that must be solved at the local level.