1. Introduction

In September 2015, the world leaders gathered to endorse seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), demonstrating a paradigm shift for people and the planet built on “shared values, principles, and priorities for a common destiny” [

1] as stated by the UN Secretary General Baan-Ki Moon. The notion of

shared values refers in this sense to values contributing to sustainable development. With an inclusive approach, the SDGs put emphasis on private sector participation by including civil society organizations and businesses in the negotiation process, consequently legitimizing the SDGs and creating incentives for companies to engage [

2]. Two important issues raised in the consultations were to “create a systemic change in order to better measure and value true performance of business” [

3], and to integrate sustainability into long-term risk assessments and core business strategies [

3]. The first issue deals with the quality and application of methods to appropriately determine social and environmental impacts, which subsequently serves as decision support for defining company priorities and orientation of efforts. The second issue concerns the integration of sustainability into business strategies, not as a complement, but rather as something permeated in all business operations and decisions. Both issues lead back to the proclaimed paradigm shift built on shared values for a sustainable future as demonstrated by the SDGs.

Sustainability reporting as a form of corporate communication refers to the way in which companies communicate its sustainability commitments and performance to its stakeholders [

4]. According to the 2017 KPMG survey on sustainability reporting, among a sample of 4900 companies worldwide including the 250 largest companies, the SDGs are fueling demands for impact data [

5]. Non-financial disclosures, including the SDGs, are for instance requested from investors as decision support to make sustainable investments. To make sustainable investments, capital should be directed to companies that, apart from seeking profit, want to contribute to a better world. Sustainability reports may therefore play a significant role in attracting investor capital. In this sense, sustainability reporting, as part of a company’s communication strategy, may expand the scope of value-based stakeholder relationship from one that benefits the company and its stakeholders to one that also creates value for society at large [

6]. The scope of disclosure, positive and negative progress reports, is also part of the communicational strategy [

7].

Approximately four in ten sustainability reports in the KPMG survey make a connection between business activities and the SDGs [

5]. This is a clear trend that has emerged in a short period of time and strongly suggests that the SDGs will continue to serve as a growing profile in sustainability reporting in the coming years [

5]. Yet, according to the 2018 SDG reporting challenge report by PwC [

8], a gap remains between companies’ intentions and their ability to embed the SDGs into the core business. Only 23% of 729 reviewed sustainability reports across 21 territories disclose meaningful targets and Key Performance Indicators (

KPI, Key Performance Indicators “are a set of quantifiable measures that a company uses to gauge its performance over time. These metrics are used to determine a company’s progress in achieving its strategic and operational goals” [

9]) related to the SDGs [

8]. According to the study, the reason for superficial engagement may be due to inadequate guidance on how to measure impact in key areas. Previous research on sustainability reporting focuses on, for example, human relation management [

10], leadership that is guided by values [

11], employment forms [

12], performance measurements [

13], gender aspects [

14], and sustainability reporting as a part of branding [

15]. All of these aspects serve as grounds for understanding context bound motives, ambition levels, and formats for sustainability reporting.

The retail industry, including the apparel sector, are among the first adopters to integrate the SDGs into their sustainability reports. According to KPMG, 57% of the companies connect their sustainability work with the goals [

5]. Yet, a qualitative integration of the goals is still in an early stage for most companies [

8]. Aditionally, there is currently no uniform practice for how businesses measure and communicate their impact and progress on the SDGs. Until recently, most companies used reporting standards pre-dated to the SDGs [

16,

17,

18]. Although the existing frameworks are comprehensive and thorough, the complexity and sheer volume of the various targets and indicators hinder many companies, especially small and medium-sized enterprises from reporting on their sustainability performance and contributions to the SDGs. Despite the various procedures for reporting, the research question relates to the perceived value of SDG integration in corporate apparel communication. A discourse analysis was conducted on six sustainability reports published by two apparel retail companies. The study outlines theoretical perspectives and discussion with regards to value creation and sustainability reporting strategies. It further presents a conceptual framework developed for the purpose of the discourse analysis, which focuses on two variables, “communicated motives for SDG integration” and “methods to measure and report on goal fulfilment”.

2. Sustainable Development Goals and Challenges in the Apparel Industry

Challenges with reporting and communicating on sustainability impacts are evident regardless of size [

16,

19]. The textile and apparel industry, while endowed with enormous potential related to the development of countries given its labor-intensive character and easy start-up, has drawn increased attention to its negative impacts along the value chain [

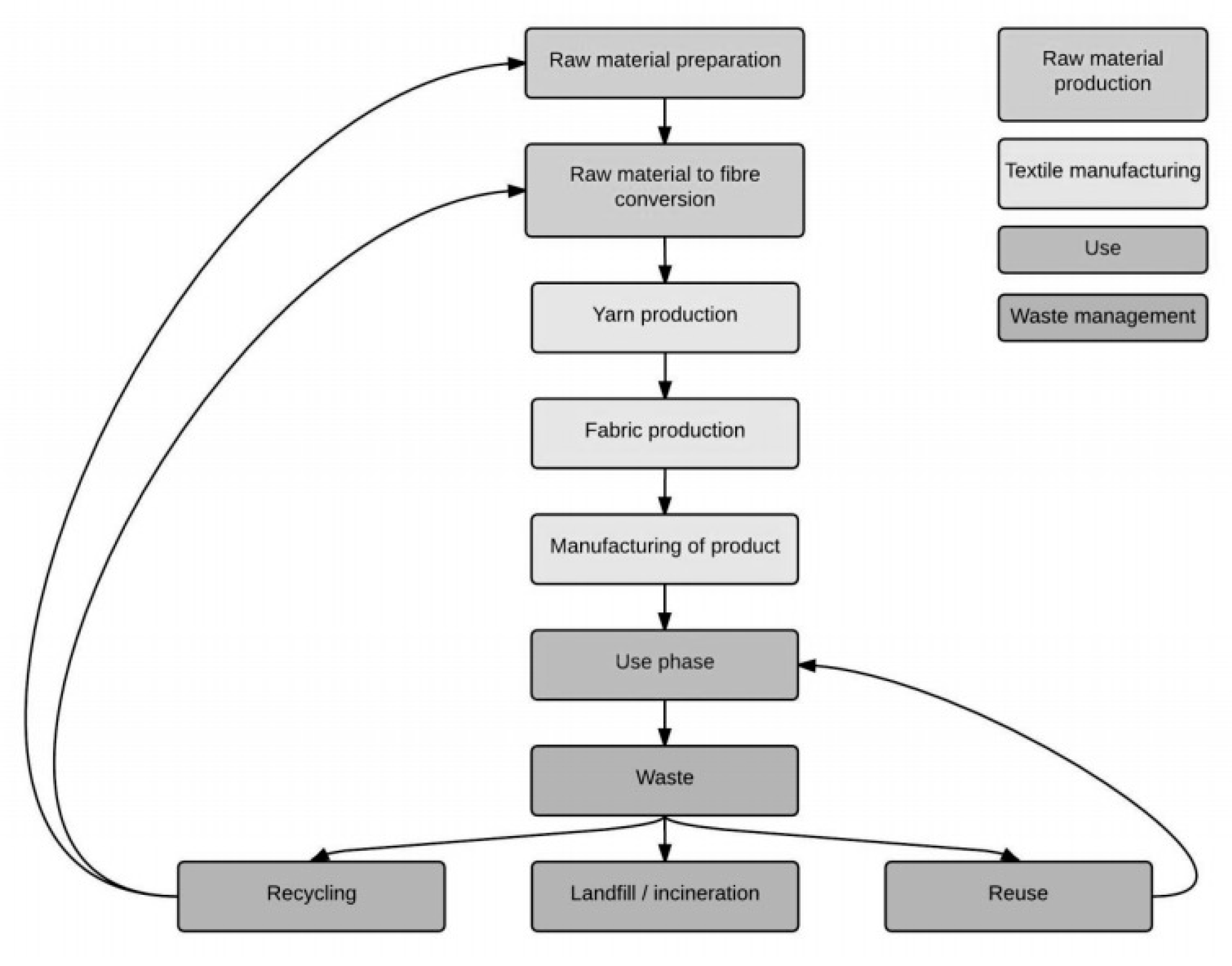

20]. Most apparel supply chains are long and complex. What might be seen as an integrated network is often depicted as a simplified value chain for an apparel product life cycle (

Figure 1). These value chains are global and decentralized, and therefore particularly complex [

21]. The specific impacts of the textile and apparel industry also set the foundation for which SDGs are relevant for a company’s sustainability efforts. Although all goals are indirectly relevant as they are interconnected, assessing where the industry has greatest impact-focused efforts may contribute to value creation for sustainable development if goals are appropriately directed. Thus, a growing awareness of sustainability impacts along global supply chains creates incentives to conduct risk assessments and to communicate strategic objectives as well as outcomes in sustainability reports. The reports may serve as part of a strategy to mitigate negative feedback from stakeholders or to attract benefits such as investment capital [

22].

All stages (

Figure 1) in the life cycle of a garment have a sustainability impact. The industry employs approximately 26.5 million people globally, with women representing about 70% of the industrial workers [

23,

24], and it is specifically known for occurrences of hazardous working conditions and violations of human rights. Social issues are thus specifically relevant to SDG 5 “Gender Equality” and SDG 8 “Decent Work”.

The industry’s resource intensive production methods often involve high levels of contamination and pollution [

25]. With regards to SDG 6 “Clean Water and Sanitation”, the cotton grown for a single plain shirt require approximately 10,000 L of fresh water [

26]. The industry is further particularly chemical intensive. According to the Environmental Justice Foundation, cotton production corresponds to 2.5% of the world’s cultivated land and 16% of the global insecticides are used on the crop. This is higher than the use for any other major single crop [

21]. Resources are further “needed to transport, wash and prepare the cotton, after which it is weaved, dyed and sewn” [

27]. All of these processes create a negative ecological footprint in the form of freshwater use, the release of greenhouse gases, and chemicals which consequently affect ecosystems [

28]. Congruently, the apparel industry has been ranked as the second most polluting industry in the world after the oil sector [

25,

29].

According to the report on environmental impact in the apparel industry [

30], the only way to address environmental effects is to slow down the production—consumption cycle, i.e., slow fashion. In addition, fossil fuels need to be phased out of every aspect of the apparel value chain. The carbon footprint of the apparel industry corresponds to 6.7% of the global greenhouse gas emission, equal to the footprint of the European Union [

22]. Furthermore, the consumption and disposal of textiles are constantly increasing as the global population grows and becomes more affluent [

21], consequently adding increased demand for textile products pressured by shortened delivery times from consumers [

31]. Environmental issues throughout the value chain are therefore highly related to both SDG 12 “Responsible Consumption and Production” and SDG 13 “Climate Action”.

2.1. Aim

This study embarked from a consideration of facts; trends display increasing numbers of companies that integrate SGDs into their sustainability reports, and observations; motives and methods for integrating and communicating on the goals seem to vary, which possibly limits the added value. Given these preconditions, the aim of this study was to explain the perceived value of Sustainable Development Goals integration in sustainability reporting within the apparel industry. Value, in this case, refers to trustworthy grounds for communicating contribution to the SDGs as part of a scope that goes beyond a traditional value-based stakeholder relationship, from one that benefits the company and its stakeholders to one that also creates value for the society at large. In order to fulfil the aim, the study focused on communicated motives for working with the SDGs and the outcome of this communication in terms of SDG integration.

2.2. Approach

The importance of a value chain perspective when studying corporate communication in the apparel retail is explained by the role of connecting manufacturing and use (in

Figure 1). It is the apparel retail that can make a linear model circular through reuse and recycling. Furthermore, it is the apparel retail companies that are held accountable for the most part by consumers. An empirical case study is based on a critical discourse analysis of two Swedish apparel retail companies, Lindex and Filippa K, by reviewing publicly available sustainability reports from 2015 to 2017 [

32]. The Swedish fashion industry was chosen as it has been in the forefront of sustainability initiatives such as Mistra Future Fashion and Swedish Fashion Council. Swedish companies are further subject to the Swedish sustainability law incorporated into the Annual Accounting Act, which requires companies to establish a sustainability report. The choice of unit of analysis was based on common criteria which included:

National context where the apparel retail has operations with a global reach,

reported net sales of more than 350 million SEK on average (financial criteria for which large companies within the European Union are required to publish a sustainability report),

having officially published reports, and

communicating on the SDGs.

While sharing these common characteristics, the companies differ in many ways. Lindex is considerable larger in terms of market presence and has a turnover of almost ten times that of Filippa K. While Lindex constitutes a retailer that sells a wide range of different brands, Filippa K is a single brand company where the apparel is sold in either brand stores or by other retailers. Finally, Lindex is using the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) reporting standard for sustainable development, and Filippa K is not. The sustainability reports from both companies (2015–2017) were selected for a discourse analysis.

While an abductive research design was applied by correlating and integrating facts and observations with the help of theoretical models into a more general description and relating them into a wider context [

33], a critical discourse analysis is particularly suitable for understanding a change process [

34]. As language tends to draw on former discursive structures, language users reproduce already established meanings. This can be understood through Fairclough’s concept of intertextuality, namely how one text draws on preexisting discourses and elements of other texts [

34]. By combining elements from various discourses, communication can change single discourses and thus, the social and cultural world. Critical discourse analysis attempts to determine and unite the relationship between three levels of analysis. The first level of analysis deals with the content of the text. The second level deals with the discursive practices where the texts represent communication of an event and the construction of identity as well as strategies to frame the content in the message. The third level deals with the social context that impacts the discursive practices [

35]. Therefore, qualitative data collection was particularly suitable for the purpose of understanding perceptions and motives behind the communicated materials [

36]. Discourse analysis has been applied on the collected empiric data through the three levels of analysis.

After structuring the empiric data into a matrix, the data have been processed by first assessing the content of the respective indicator and how it has changed over time. The discourse analysis further included a search for similarities, differences, and patterns. In addition, with regards to strategies for how the variables of motive have been framed. In the case of Lindex and Filippa K, the strategies to frame the content of the message include circular economy and the SDGs. With these strategies in mind it was possible to analyze intertextuality by searching for introduction of new concepts with pre-established meanings and how these have contributed to the production of new meanings. The third level of analysis has been conducted by reviewing the correlation between the variables motive and method, but also by reviewing the results in relation to the existing research field.

3. Theoretical Perspectives on Value Creation

Value creation in this study departs from the notion of shared values and refers to values contributing to sustainable development. The value of sustainable development lies not only in the intrinsic value of a resilient earth system, but also to uphold a safe operating space for humanity [

37] which includes long-term risk management in business operations [

38].

According to Stevens and Kanie [

39] the SDGs have a transformative potential. They argue that the SDGs provide an opportunity to transform the nature of development and make environmental and social sustainability a defining characteristic of economic activity. Thus, the SDGs can “move beyond the narrow silos of action which define most development efforts” [

39], as reflected in the title given to the agenda “Transforming our world—the Agenda 2030” [

40]. As such, value creation refers to our shared experiences along with future generations’ rights to prosperity, commonly used in definitions of sustainable development. In terms of prosperity, however, one of the biggest dualisms within the sustainability discourse relates to the conflict between growth and development. Opposing ideologies rest on how to value and redefine growth, notably in the debate on value creation through Porter and Kramer’s [

41,

42] concept of Creating Shared Value (CSV) used to contest their understanding of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). CSV is argued to differ from CSR as it focuses on integrating shared values in the core business driven by positive motives as opposed to the latter, which is considered to be driven by negative drivers (ibid.).

Drawing on the debate between CSV and CSR, one can distinguish between negative (reaction-driven), positive (value-driven), and utilitarian (performance-driven) drivers of change towards sustainability within companies [

22]. In this sense, value is created as businesses take action to integrate sustainability into their business practices. The negative drivers of change come from stakeholder influence and pressures [

43], where change is viewed as a commitment to avoid negative sanctions from stakeholders. The positive drivers, on the other hand, are proactive and often voluntary. They materialize from accepting relevant and justified needs. Besides the negative and positive drivers, the utilitarian drivers are based on pragmatic considerations. The major objectives lie with long-term reputational strategies or with respect to financial, marketing, and public relations [

22]. Regardless of the drivers of change, sustainability communication “allows [a] company to show it is contributing to greater long-term shareholder value by retaining its social license” [

44]. This is facilitated by communicating progress on KPIs aligned with a long-term strategy that creates societal value [

44].

Application of Value Theory

When trying to understand how integrating SDGs into sustainability reporting creates value, value creation may be broken down into two main variables, namely motives and methods. Both variables contribute more or less to shared values. Motives refer both to the positive, negative, or utilitarian drivers of sustainability actions as described by Buelens [

22] as well as the first steps in which a company examines the case to measure impact and identify relevant impact areas in its value chain presented in

Table 1. For instance, a company producing computers may be motivated to limit the risk of conflict minerals in their supply chain after pressures from stakeholders, but also by mapping its value chain and identifying mineral extraction as a high-risk impact area. The perceived motive in this case refers to the communicated reasons for working with the identified sustainability aspect.

4. Empirical Findings

A review of the sustainability reports from 2015 to 2017 for Lindex [

45,

46,

47] and Filippa K [

48,

49,

50] serves as empirical case studies. The common SDGs reported on by Lindex and Filippa K are SDG 5 “Gender Equality”, SDG 6 “Clean Water and Sanitation”, SDG 8 “decent work”, SDG 12 “Responsible Consumption and Production”, and SDG 13 “Climate Action”. Empirical findings (

Table 2) show that both Lindex and Filippa K are using the SDGs as a communicative tool to point to the conceptual motives which drive the sustainability work. Fairclough’s concept of intertextuality is manifested by the use of concepts such as “decent work”, “climate action”, and “responsible consumption” prevalent in both Lindex and Filippa K’s sustainability reports.

Empirical findings show that the companies did not follow the steps according to the SDG compass (

Table 1), yet were able to report on contribution to the SDGs. Lindex displays discursive changes related to motive between 2015 to 2017, representing an extended scope of responsibility. Filippa Ks communicated motives, on the other hand, are inconsistent. Nevertheless, Filippa K’s sustainability reports show that although the company did not communicate an understanding of the sustainability issues they aspire to work with, the methods used to integrate sustainability into their business are similar to Lindex that in their reports provide an extensive and advanced communicated level of awareness over time. Filippa K also shows progress over time in terms of accelerated initiatives motivated by participation in industry dialogue concerning circular fashion. In terms of congruency between communicated motive and quality of the method: If Filippa K would have conducted an extended impact assessment of their value chain and thereby provided a more solid foundation for their motives, the communicated focus on social aspects in their supply chain could possibly be strengthened.

Filippa Ks KPIs show both high and low levels of data quality. The data presented in relation to goal fulfillment, namely materials and fibers, are clear, comparable, and appear accurate. The company discloses composition of fibers in charts and tables with information on the proportion of materials and fibers used, which is interpreted as transparent and reliable. However, the KPI for climate action is not comparable or clear, and therefore it appears inexplicit. Lindex carbon emissions data are communicated in a table with progress over time presented in both figures and percentages. Overall, all of the Lindex data is compiled, calculated, and presented according to the GRI Standards, which consequently affect the perception of quality of the disclosed information and is thus seen as reliable.

5. Analysis and Discussion

According to the GRI, UNGC, United Nationsl Global Compact, and WBCSD, World Business Council for Sustainable Devleopment, by utilizing the SDG compass (

Table 1), companies can create shared values [

51]. This means that by first understanding the SDGs and then following the next four steps including impact assessment, goal setting, anchoring, and reporting, sustainability performance may be accelerated as the processes is repeated over time. Thus, in theory, by integrating the SDGs in the annual cycle of sustainability reporting and management, shared value is created, and progress should be demonstrated over time as a part of communication for a better world. However, as in the cases of Lindex and Filippa K, companies do not always follow the steps according to the SDG compass. Although sustainability reporting is a method to increase transparency and be held accountable to stakeholders [

17], there may be a discrepancy between action and what is communicated. The implications of the empirical study are further discussed in terms of theoretical and managerial implications.

5.1. Theoretical Implications—Sustainability Communication

Challenges associated with sustainability communication and reporting are constantly subject to scrutiny [

52] that calls for reinvention of communication approaches [

53]. According to Elving et al. [

54], corporate sustainability is increasingly equated with transparency and accountability. However, on many occasions, the idealism of sustainability communication diverges from the reality of daily business operations. Sustainability initiatives are sometimes perceived simply as opportunistic tactics to win public approval while covering dubious practices [

22]. Lack of congruency between communication and action is explicitly expressed in terms like “green-washing”. Such metaphors illustrate perceived discrepancies between talk and action [

54]. Problematic situations like these contribute to a perception of arbitrariness and hypocrisy. Sometimes “with the paradoxical consequence that the sincerity of company managers’ motive is questioned even when their [sustainability] efforts are genuine” [

22]. Sincerity, in this context, is the level of conformity between discourse and practice and congruity between words and deeds [

22]. In other words, sincerity can be perceived as “walking the talk”.

In cases of limited sustainability communication, an aspect to consider is that sincere and positively motivated companies may not have the capital or capacity to execute an extensive sustainability report. Furthermore, for companies that just embarked on their sustainability journey, it may take a couple of years until they have produced and implemented sustainability policies, educated all their employees, set goals, action plans, and implemented systems for collecting data. This does not mean that they are not working with sustainability, but rather that its systematic sustainability governance is maturing within their organization [

55]. The potential value of the sustainability performance within a company may thus not be seen after a couple of years. In these cases, a discursive change should be evident in the sustainability communication over time.

5.2. Managerial Implications—Circularity as Motive and Strategy

Discourses on sustainable development are constantly given new meaning in different genres as it is merged with other discourses and practices [

56]. Sustainability reporting has, according to Zappettini and Unerman [

56], emerged as a new hybrid discourse through which organizations interlink financial information with the social and environmental impacts of their activities. They argue that discourses of sustainability have been re-contextualized into macroeconomic discourses and that intertextual and interdiscursive relations also have conditioned the evolution of sustainability discourses [

56]. This is evident in the intertextual discursive strategies to frame Lindex and Filippa K’s sustainability methods by integrating the concept of circularity. The findings show that both companies are using the SDGs as a structural tool for corporate communication to point to the conceptual motives which drive the sustainability work. Circularity in the apparel industry is directly linked to values associated with SDG 12, as well as indirectly to SDG 6 and SDG 13 through and outside in a perspective where the apparel industry has understood the marketing value of circular business strategies. In Filippa Ks case, branding business operations as “circular fashion” goes in line with Porter and Kramer’s [

42] argument that shared values can be used as a driver for economic growth. By reproducing concepts with pre-established meanings related to the SDGs in economic discourses, value is created by providing a common language with a shared purpose and meaning in a new context.

5.3. Impact Assessment as a Means to Identify Relevant Sustainable Development Goals

Although sustainability reporting is a form of communication, it differs from merely spreading information to educate the public, as it is the practice of “measuring, disclosing, and being accountable to internal and external stakeholders for organizational performance towards the goal of sustainable development” [

4]. In the case of Filippa K, the company communicates on SDG 5 and SDG 8 in its reports. This indicates an awareness of social impacts along their value chain. Transparent communication of motives such as explaining how and why the aspects are material is however lacking, and methods to address the issues may be deemed as insufficient as merely minor progress is communicated over the years. This study supports Einwiller and Carrol’s [

7] findings that much of sustainability disclosures are aimed at reporting about progress in positive messages. Negative disclosures relating to failure and challenges are rarely communicated. It further supports the idea that an understanding of the issues behind the SDGs affects which methods are used to contribute to the goals. This also supports the concern raised by Pingeot [

3], which deals with the quality and application of methods to determine social and environmental impacts of companies, which subsequently serves as decision support for defining company priorities and orientation of efforts [

57]. Hence, it is not only awareness of the impacts that are relevant, but rather how the knowledge is utilized.

In terms of goal setting, both cases show improvement over the three years, particularly in the 2017 reports. In order to contribute to SDG, fulfillment goals should be specific, measurable, and time-bound, as they are easier to track and advance as progress or stagnation becomes explicit. Although both companies link their goals to the SDGs, none of the companies have broken down the SDGs into sub-targets, but rather use internal goals to communicate contribution. Empirical findings show that goal setting within Lindex and Filippa K differs depending on the SDG. Neither of the companies present specific goals related to gender equality, water, or climate change, but rather bigger overarching goals which encompass these issues. Formulation such as “ambitions”, “strives”, “looking into the future”, and “overall aim” are prevalent in both cases and are neither specific, measurable, nor time-bound, and has therefore limited value. While they are valuable in terms of normative notions representing the will to work with sustainability issues, they also risk being interpreted as green washing, as they allude to communication strategies without action, as argued by Buelens [

22].

Filippa Ks goals “only sustainable materials” and “only recyclable styles” along with the Lindex goal “by 2020 all cotton Lindex use will come from sustainable sources and at least 80% of our garments will be produced with more sustainable manufacturing processes” [

46] all aspire to reduce consumption of water, energy, and chemicals which contribute to SDG 6, 12, and 13. The goals per se are ambitious, highly relevant, quantifiable, and, in the Lindex case, time-bound, yet they are not communicated rather specifically. Furthermore, “reduced amounts of water, energy, and chemicals” does not reflect the level of ambition for which reductions are made. Hypothetically, if 100% of the garments could be produced using 2% less water, energy, and chemicals while at the same time the production volume increases 30%, the environmental impact would be higher than the potential outcome from the ambition of the set goal. Thus, a crucial point in terms of value creation when it comes to goal setting is level of ambition and appropriate goal setting that goes in line with company growth. As such, the ambition level affects the value and structure of the goals with the risk of limiting the value if not defined appropriately.

5.4. Methods to Facilitate Sustainable Development Goal Contributions

Goal fulfilment depends on an effective integration of the goals into everyday business practices. Although both Lindex and Filippa K are exploring methods to recycle fibers and collect clothes in their stores, the acceleration of initiatives between 2015 and 2017 are most prevalent within Filippa K, which also communicate an emphasis on responsible consumption. Use and disposal of a garment is directly affected by consumer behavior. Each option has environmental impacts and benefits. Methods to prolong the life of a garment creates value in support of sustainable development. According to Quantis [

30], the only way to genuinely address circular fashion is to slow down the cycle of garment production and consumption. In both cases, methods to facilitate progress with SDG 8, decent work, relate to audits. In both cases, audits are communicated to secure labor rights. Conclusions from previous research by Muthu [

28] argue that there is a correlation between companies’ procurement practices that push for a reduction of production costs, which have a negative effect on labor standards such as living wages and working hours. With regards to procurement relationships, findings from both cases indicate long-term supplier relationships which show a potential for increased leverage that may facilitate consolidation of shared values such as human and labor rights.

Communicating on KPIs does not necessitate benchmarking against goals, as seen in the case of Lindex and Filippa K. A disconnection between data and goal does not limit contributions to the SDGs if the data relates to the orientation of the goal, however the quality of the data may affect the level of the value. According to the GRI [

17] reporting standard, quality data correspond to information that is comparable, reliable, accurate, and clear. In terms of reporting on KPIs, findings show that data disconnected from goals have lower quality in the reports. Although communicating on KPIs does not necessitate benchmarking against goal setting, as seen in the case of Lindex and Filippa K, the quality of the disclosed information affects the value. Given that a part of the value of the reported performance indicators is comparability, it is important that the structure of reporting is consistent over time. Data presentation that lacks information on context does not give an indication of whether the data are unusually high or reasonable, which limits the quality and effect of its proposed value [

58]. Quality data further suggest that by reporting on sustainability performance in the same measurement as acknowledged frameworks, the sustainability benchmark is simplified. It may also facilitate internal changes as it triggers performance reviews. Ideally, value creation should be measured with accurate, reliable, consistent, and comparable data. This means that qualitative data is more likely to reflect true performance [

3] and will help companies’ direct efforts to where they are most useful, rather than where the business case is easiest. Data presentation, regardless if it is qualitative or quantitative, should further be presented so that stakeholders, such as investors and customers, can make substantiated decisions [

7,

18].

According to Elkington [

59], only companies that, apart from measuring economic performance, also measure social and environmental performance are taking account of the full cost of doing business. The triple bottom line is useful for companies as it is directly applicable. However, a significant challenge with measuring impact is evident through the notion of externalities, i.e., the hidden cost of production. Externalities are with other words the indirect impact of production and consumption, which is not included in the price of the good or service [

60], such as air pollution. Given the indirect impacts, an extended scope of value creation is important for companies that attempt to get an accurate picture of the true impacts along their value chains. Yet, given that there is no uniform practice to measure [

16] and accurately determine sustainability impacts, measurements will continue to be flawed as argued by Pingeot [

3].

5.5. Connection between Communication and Value Creation for Sustainable Development

The two issues raised by business leaders in the consultations leading up to the formulation of the SDGs was to measure and value true performance of business more accurately and to integrate sustainability into long-term risk assessments and core business strategies [

3]. Both issues lead back to the proclaimed paradigm shift built on shared values for a sustainable future demonstrated by the SDGs. The cases in this study have been reviewed according to the five steps in the SDG compass to deal with these issues. By reviewing whether there is a qualitative connection between motive and method and a connection between communication and SDG contribution, there is a theoretical support indicating that a strong connection creates shared values related to sustainable development, as it is more likely to direct efforts to where they have a greater impact.

Empirically, there is however an issue that the business world is more complex than something that can be assessed in a black and white dichotomy of communication and action, and needs a much more sophisticated approach to bridge the gap between promise and performance as argued by Buelens [

22]. As seen in the cases of Lindex and Filippa K, SDG integration does not necessarily need to be carried out in accordance with the steps in the SDG compass. It is possible to create value and contribute to the SDGs without having goals that guide actions or an impact assessment that guides methods. However, the quality of the communicated content will have an effect on how trustworthy the company is perceived in terms of connection between communication and action. Limited sustainability communication should initially not be regarded as insignificant, as companies with less reporting experience need time to create internal processes. SDG integration depends on many factors, such as competence, knowledge, and capacity to realize efforts. However, this means that progress should be visible discursively over time. As a company matures in its sustainability management processes, the quality of communicated motives and methods tend to increase, which consequently affect SDG contribution and value creation.

The maturity of corporate sustainability communication may come from internal drivers, but also from external influence such as investor and customer demands. Regardless of whether the development is sprung from negative, positive, or utilitarian drivers, the connection between action and communication is more likely to contribute to creation of shared values if the change process has a value chain approach [

6]. In the case of the apparel retail companies reviewed in this study, both companies take into consideration sustainability issues that go beyond the company’s primary operations to also include issues in the supply chain and consumer phase of its value chain. With a strong connection between motive, method, and performance, the SDGs are not only expanding the scope of impact and value by serving as guiding principles for corporate conduct. They may also be perceived to expand the scope of a value-based stakeholder relationship from one that benefits the company and its stakeholders to one that also creates value for the society at large [

6] if integrated appropriately.

From a macro perspective, expanding the scope of impact and value can be seen as an example of how discourses of sustainable development are continuously evolving, in support of Zappettini and Unerman [

56] who argue that sustainability reporting has emerged as a new hybrid marketing discourse through which organizations interlink financial information with the social and environmental impacts of their activities. By integrating the SDGs into sustainability reporting, the discourse is added with more intertextual and interdiscursive characteristics that expand the scope of impact and value.