1. Introduction

Specialized farmers’ cooperatives (“cooperative” hereinafter) in China are mutual economic organizations based on rural household contract institutions, in which agricultural producers or agricultural service providers and users are cooperating on a voluntary basis. Their members produce same kind of agricultural products or provide services for production of these products. Cooperatives mainly serve their members in purchasing inputs, marketing, processing, transporting and storing agricultural products, and providing new technologies and information. Due to the characteristics of cooperatives, such as mutual-help orientation, geographically limited activities and commitment to community development, it is expected that the cooperative system takes naturally into account social responsibilities [

1].

In recent years, the number of Chinese cooperatives has increased rapidly (see

Figure 1). By the end of October 2019, 2.203 million farmers’ cooperatives were registered. Almost half of farmers in China were members of cooperatives. The average annual income of a cooperative member was 32% higher than that of a non-member, which shows that the cooperatives could have a great potential in China’s rural revitalization [

2]. However, due to resource constraints, blind promotion of cooperatives by the administration, excessive pursuit for profits, and other reasons, Chinese farmers’ cooperatives have a high rate of empty shells and poor vitality [

3]. The average lifetime of cooperatives in China has been less than 3 years [

4], and the proportion of empty-shelled cooperatives reaches 30–60% [

5]. Thus, the development in the starting phase of many farmers’ cooperatives has not been successful and economically viable, which is undesirable in many respects.

In this context, studying the cooperative social responsibility is of great importance. However, most of the prior researches focus on corporate but not cooperative social responsibility. The research shows that although corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities of the company can be driven by business ethics and reputation, they are also attractive due to the search for competitive advantage and therefore, also related to the opportunistic goals in the firm strategy. Accordingly, the demand for CSR comes from consumers and the company’s stakeholders [

6]. The ability to meet the requirements of CSR are related to the company’s financial performance and the availability of slack resources [

7]. If ethical/reputation concerns and financial performance vary with the life cycle of the company, it is likely that CSR activities and the life cycle are interlinked [

6,

8]. Hasan and Habib [

8] argue further that richness of resources and better financial performance allow mature firms to invest more in CSR activities than early-stage firms.

Firms at different phases of their life cycle are associated with different resources that shape their CSR behavior. Penrose [

9] presents a general theory of the growth of the firm and argues that firms’ growth depends on their resources and production capabilities. Therefore, Helfat and Peteraf [

10] state that the resource-based view must incorporate the development of the firm’s resources and capabilities over time and, hence, they introduced ‘‘the dynamic resource-based theory” as a follow-up to the resource based view by Wernerfelt [

11] and the resource based view of competitive advantage by Barney [

12]. The “dynamic resource-based theory” refers to general patterns of changes in the firm’s capabilities over time. Therefore, it is important to understand the associations between the phases of life cycle and CSR involvement [

8]. It is especially interesting to see how these two are interlinked in the evolution of producer cooperatives.

In China, there are very few studies on cooperative social responsibility (CoopSR) and cooperative’s life cycle. Therefore, we construct a “life cycle-cooperative social responsibility framework (LC-CoopSRF)” and discussed different social responsibility targets. In order to further explain the inherent logic in this design, we refer to Lee and Choi’s [

13] research and introduce operational capacity and ethical expectations as the main conditions for analysis. Our main research problems are: How should cooperatives fulfill their social responsibilities over time, and what are the aims and means of fulfilling them? In order to verify that the “LC-CoopSRF” is reproducible and operational, we analyze a successful cooperative case, Chongxin Apiculture Specialized Cooperative of Qionglai, Sichuan Province. CX Cooperative was established in 2007 and the business has been growing for more than ten years. It has gone through the predefined phases of the life cycle and provides an interesting case study to this article.

3. A Case Study

In the following, we first introduce the case, and then apply the “LC-CoopSRF” as delineated above to analyze the social responsibilities of CX Cooperative in different phases of the life cycle.

3.1. Case Context

The object of this case study is Chongxin Apiculture Specialized Cooperative of Qionglai, Sichuan Province (“CX Cooperative” hereinafter). By the end of October 2019, 103,000 cooperatives had been registered in Sichuan. However, according to the survey, only 10% of cooperatives were in fact running [

31]. CX Cooperative was founded in 2007 and has developed for more than ten years. It has gone through a relatively complete life cycle, which can provide explanation and reference for this study.

CX Cooperative was founded in 2007 by Wang Shun and his colleagues. Through development over the past ten years, the registered capital of CX Cooperative is now 18.75 million yuan and there are 436 members who are from Qionglai and its neighboring counties/districts/cities, and even from Mianyang, Ya’an, Ganzi Prefecture, Liangshan Prefecture, A’ba Prefecture, Panzhihua, Gansu, Ningxia, and Guizhou; and there are more than 90,000 swarms, with over 4000 tons of annual production of bee products, over 60 million yuan of annual output value, and over 10 million yuan of accumulated dividends for farmers raising bees. The nectar source involves over ten provinces including Sichuan, Henan, Shanxi, Gansu, Ningxia, and Qinghai. Chongxin Bee Breeding Station, Chongxin Apiculture Association, and Chongxin Biotechnology Co., Ltd. have been established, and 7 brands, i.e., Chongxin, Home of Nectar, Holy Bee Hall, Holy Bee Valley, Tianlekang, and Bestowed Nectar, have been registered. Its products include honey, royal jelly, bee pollen, propolis, and so on.

3.2. Methods and Data

This study applies the case study method. The case study is a research strategy, which focuses on understanding the dynamics within single settings [

32]. Case studies usually need to pay attention to four issues: making controlled observations, making controlled deductions, allowing for replicability, and allowing for generalizability or transferability [

33]. Compared with other research methods, case studies can not only describe the case in detail and understand it systematically, but also control the interaction processes and context of the case [

34]. Case studies always employ an embedded design, that is, multiple levels of analysis within a single study [

35]. As earlier studies on life cycle and social responsibility mainly focus on corporates rather than cooperatives and as it is almost impossible to collect a representative statistical panel dataset from Chinese cooperatives, the longitudinal case study is in practice the only applicable approach for our study. We also carefully examine the business conditions at each phase and include them in the case analysis.

Case studies typically combine data collection methods such as archives, interviews, questionnaires, and observations [

32]. In a depth analysis of the cooperative case, we use several data sources. The digital data comes from government websites such as the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China, Sichuan Provincial Department of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, and research articles and news that have been published, and annual reports of the cooperative. The introduction of the cooperative comes from the cooperative website. The practice of cooperative’s social responsibility comes from online interviews of the manager and other related personnel of the case. We also conducted a field survey in August 2019. Thus, we utilize triangulation, which increases the reliability of our results.

3.3. Analysis from the “LC-CoopSRF”

In this part, we first analyze the realistic conditions of CX Cooperative in different life cycle phases from the perspective of operational capability and ethical expectations, and then analyze the social responsibility activities of CX Cooperative. According to the interviews with cooperative manager and field survey, we determined the life cycle phases of CX Cooperative: establishment (2007–2009), growth (2010–2014), maturity (2015–2018), differentiation (2019). Besides, as the main business of CX Cooperative is the production and sales of bee products, with the development of the characteristic fruit business of CX Cooperative, we have reason to believe that CX Cooperative has entered the phase of re-development.

3.3.1. Establishment

Conditions Analysis

CX Cooperative was established in November 2007; this year is also known as the first year of Chinese cooperatives. In July of that year, China promulgated the “Law of Farmers’ Specialized Cooperative of PRC“, and cooperatives have embarked on a path of development in accordance with the law. However, due to the failure of the Chinese cooperative movement in the 1960s, most farmers had no expectations or even doubts about the cooperatives, and their enthusiasm for participation was not high. By the end of 2007, there were only 26,400 registered cooperatives in China. In this context, as a first mover, Wang Shun, an old bee farmer, selected some bee farmers with good scale and reputation to build CX Cooperative together. At the time of establishment, CX Cooperative had only 22 members and 6500 swarms. Due to the small number of members, limited assets, and large funding gaps, CX Cooperative faced great pressure to survive. At this time, survival is the primary goal of CX Cooperative, and maintaining existing members and attracting new members through social responsibility activities have become an important means of survival.

Social Responsibility Activities

Due to the limitation of operational capability and no requirement of ethical expectations, the social responsibility of cooperatives during the establishment phase mainly revolves around members, which we call bottom-line responsibility. CX Cooperative implemented a number of measures to achieve bottom-line responsibility.

CX is an apiculture cooperative and beekeeping is a special profession. Due to different flowering times of plants and varying climatic conditions, bee farmers must travel around the country to collect honey (see

Figure 4). In order to provide protection for its travelling members, CX Cooperative purchased personal accident insurance for all members. In the process of collecting honey, members often suffer from bee poisoning, and even extortion and other problems. CX Cooperative has hired a legal advisor since 2009, in order to maintain the members’ legal rights and obligations. Meanwhile, CX Cooperative also actively invited experts and researchers to train the members on relevant laws and rules, newest policies, product quality safety, and new technologies. Through the implementation of social responsibility actions towards its members, CX Cooperative passed on a member-oriented cooperative service concept, which attracted the surrounding bee farmers to join. The cooperative gradually expanded laying a foundation for its rapid development.

3.3.2. Growth

Conditions Analysis

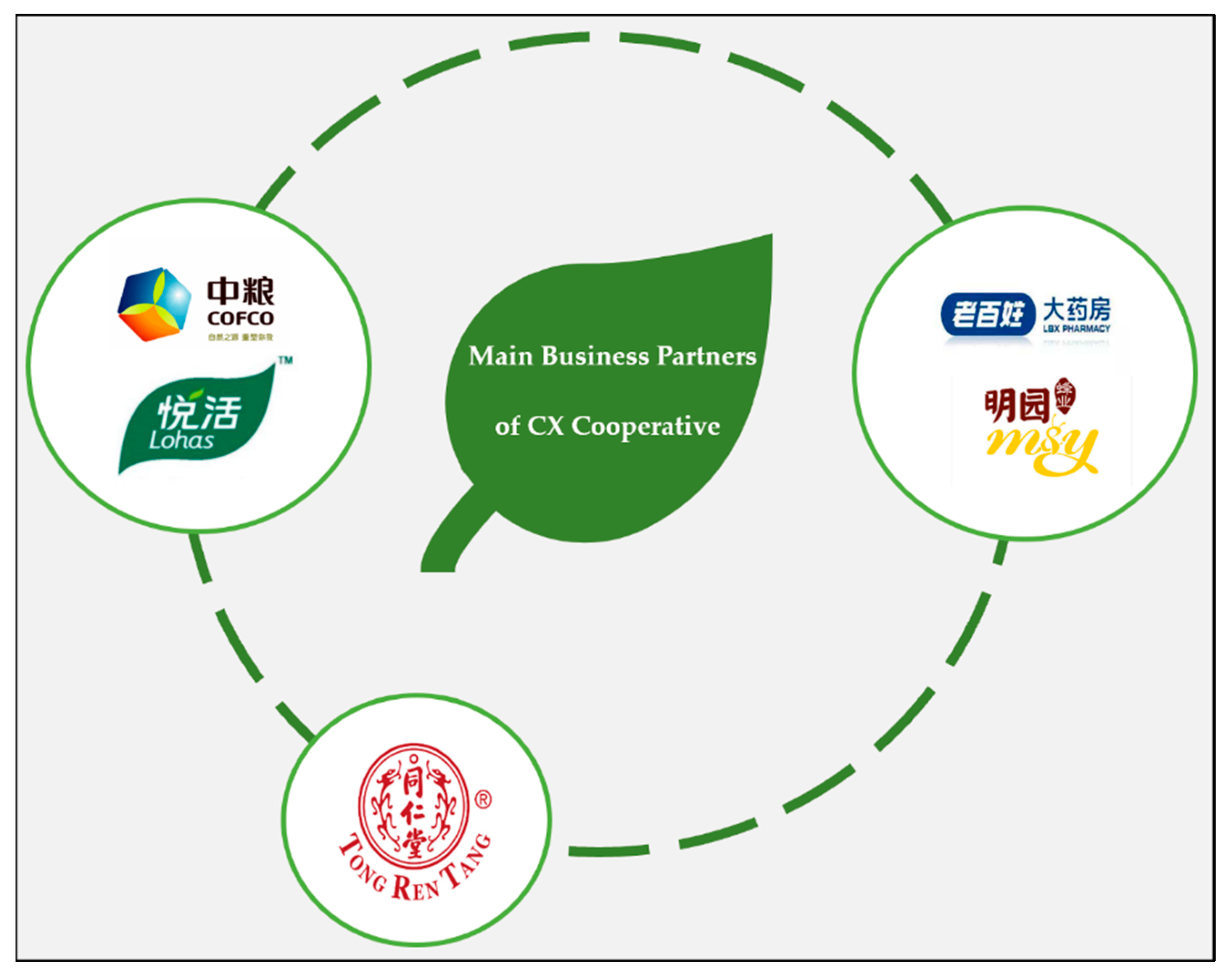

The growth phase of CX Cooperative is from 2010 to 2014. After the exploration and development during the establishment phase, when CX Cooperative entered the growth phase, the number of cooperative members had increased from 22 to 111, and the number of bee swarms had increased from 6500 to 33,690. The annual output of bee products reached 1500 tons, and the annual output value reached 20 million yuan. CX Cooperative had gradually increased its operating capabilities, but funds were still insufficient, and a large amount of funds were needed for industrial chain improvement and brand building. After entering the growth period, the ethical expectations faced by CX Cooperative also increased. On the one hand, with the increase in the size and profitability of CX Cooperative, the expectations from members and employees increase. On the other hand, CX Cooperative began to establish fixed cooperative relationships with listed companies such as Tongrentang and China Oil & Foodstuffs Corporation (COFCO) (see

Figure 5), and the ethical expectations of business partners had a very important impact on the social responsibility of CX Cooperative. In this context, establishing a stable trust relationship with target groups such as members, employees, and business partners through social responsibilities is more conducive to the survival and operational continuity of the CX Cooperative. That means that CX Cooperative should take internal responsibility.

Social Responsibility Activities

In the growth phase, CX Cooperative implemented a number of measures to achieve internal responsibility.

A successful cooperative may seek opportunities to expand or to meet the additional needs of members [

16]. CX Cooperative noticed this and implemented a series of measures. In 2010, CX Cooperative established a mutual risk reserve system, which was funded by government subsidies, cooperative surplus reserves, and members. In the same year, CX Cooperative spent 1.6 million yuan to help the members solve the transportation problems of bees and feeding sugar due to poor honey harvest. Retirement has always been one of the concerns for Chinese farmers. In 2011, CX Cooperative established the endowment insurance system, and the members could get subsidy for endowment insurance according to the quantity and quality of honey they had handed in, which greatly increased the enthusiasm of the members. Although CX Cooperative organizes training for members every year, the members are generally not well-educated and they are poor in learning ability, which greatly affects the training outcome. With this in mind, in 2014, CX Cooperative compiled a Summary and Definition of Related Laws, Rules and Policies on Apiculture for members [

36], which helped members improve their beekeeping skills more systematically.

In the growth phase, with the expansion of scope of operations and business needs, CX Cooperative began to hire professional managers. Engaging talented individuals by fulfilling social responsibilities is something that CX Cooperative had to consider. CX Cooperative provided employees with training, holiday gifts, performance rewards, and other benefits, and also regularly organized Outward Bound. The current manager of CX Cooperative, Shi Ling, has been employed by CX Cooperative since 2009. She highlights that everything the cooperative has done for the employees has increased her engagement to work in the CX Cooperative so far.

Social responsibility of the cooperative towards its business partners is also important. In order to ensure product quality, CX Cooperative established a quality traceability system and an electronic traceability information management system. The personal information of bee farmers is marked on the packaging of each batch of products so that processors can inquire about the source information of each bottle of honey. From 2013, CX Cooperative established long-term strategic cooperation with listed companies such as Tongrentang, COFCO, and LBX Pharmacy, and became one of the three constant suppliers of bee products of COFCO in 2016. In order to create as much profit as possible to its partners, CX Cooperative chose to bear its own risks in the export business, which further deepened the trust of its partners. In addition, CX Cooperative also entered into a cooperation relationship with Sichuan Agricultural University and other institutions, and built an integrated system of “industry-university-research”.

For apiculture cooperatives, bees are the precious resources. In order to ensure the health of bee swarms, CX Cooperative began to purchase standardized beehives and beekeeping trucks since 2010. In 2012, new bee species were introduced from the Institute of Bee Research of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences and Jilin Bee Breeding Station, and Chongxin Bee Breeding Station was founded in order to ensure the availability of new bee breeds [

37].

3.3.3. Maturity

Conditions Analysis

The maturity phase of CX Cooperative is from 2010 to 2014. After several years of development, when the CX Cooperative entered the mature period, it already had a good operational capability, the number of members increased to 260, and the number of swarms reached 60,000. The annual production capacity of bee products reached 3000 tons and output value reached 40 million yuan. In 2015, over 60 members of CX Cooperative invested 12 million yuan to establish the Chongxin Bee Processing Factory. In August, “Temptation of Honey”, which is the first packaging product of the cooperative, was introduced. With the establishment of online marketing channels such as Tmall, Taobao, Jingdong, and other e-commerce platforms, the whole-industry chain of bee products of CX Cooperative had been formed.

At the same time, the ethical expectations faced by CX Cooperative had become complicated. In addition to expectations from internal target groups such as members and business partners, CX Cooperative need to face more expectations from society and government. In 2015, CX Cooperative won the title of National Demonstration Farmer Cooperative, which is the highest honor of the Cooperative in China. According to the requirements of the “Interim Measures for the Evaluation and Monitoring of the National Demonstration Farmer Cooperative”, the national demonstration cooperatives should have a good social reputation and create huge social benefits, which means that CX Cooperative should fulfill more social responsibilities. In addition, as the role of cooperatives in China’s economic and social development is becoming more and more important, the Chinese government has also formulated a series of policies and regulations to guide the development of cooperatives (see

Table 2), which also invisibly increases ethical expectations for CX Cooperative.

Social Responsibility Activities

We call the social responsibility activities of cooperatives in the mature phase as system responsibility. The target groups of responsibility include members, employees, partners, government, society, etc.

For members, the social responsibility of CX Cooperative continues to upgrade. In 2015, CX Cooperative established an information service platform, the purpose of which is to timely transmit information such as new beekeeping technologies, new materials, product prices, and honey sources to members through the mobile phone SMS platform. For employees, CX Cooperative opened up the promotion channel and gave employees more management participation rights. In 2015, Shi Ling became the project manager of CX Cooperative. Three years later, she became the manager of CX Cooperative. For bees, the social responsibility also continued. In 2015, the International Apicultural Congress designated 20 May as International Bee Day. The goal is to strengthen measures aimed at protecting bees and other pollinators. CX Cooperative actively responded to the proposal of the International Apicultural Congress. Starting from 2016, it held a popular science event every 20 May to call on people to protect bees.

Consumers are the end users of the products and services of the cooperatives. The social responsibility of cooperatives towards consumers is mainly reflected in providing high-quality products and services and satisfying the different needs of consumers [

30]. In 2016, CX Cooperative spent 2 million yuan to increase the number of bee product testing items from 26 to 48, which further ensured product quality. By the end of October 2019, 2.203 million cooperatives were registered in China, but only 87,000 cooperatives had registered trademarks, and only 46,000 had passed agricultural product quality certification [

2]. CX Cooperative not only owned 7 registered trademarks, but also achieved Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) Certification and EU Organic Certification in 2018, which helped satisfy the high-quality needs of customers.

The social responsibility of cooperatives towards the government includes complying with laws, using government project funds in strict accordance with regulations, and assisting the government in building villages [

30]. The CX Cooperative successively completed the “Central Finance Supported Farmers’ Special Cooperation Organization Project” and the “China-Europe Natural Forest Protection Project”, which had been recognized and affirmed by governments at all levels. In 2018, CX Cooperative actively participated in Qionglai City Government’s counterpart assistance to Jiuzhaigou County, which included both making donations and helping Jiuzhaigou County build a breeding demonstration base.

“Concern for Community” is one of the seven principles of the International Cooperative Alliance. Cooperatives should promote community development through social responsibility. CX Cooperative organized a series of activities such as charity sales and caring for the old Red Army to promote community development. Especially in terms of poverty eradication, CX Cooperative was successful. Since 2015, CX Cooperative successively trained more than 480 women bee farmers in poverty-stricken areas and ethnic minority areas such as Ganzi, A’ba, Liangshan, etc. In 2017, it established a branch cooperative of apis cerana raising to provide more technical help to poor people. With the help of the CX Cooperative, the annual per capita income of the poor people involved in beekeeping is more than 30% higher than the average local rural annual per capita income.

The CX Cooperative is also concerned about the natural environment. Since 2017, CX Cooperative implemented the “0 pesticide” system in its own honey sources to improve the quality of bee products and reduce environmental pollution.

The social responsibilities of CX Cooperative in the mature stage are comprehensive and systematic. On the one hand, increasingly improved operational ability, sustained profitability, and accumulated capital assets can support CX Cooperative to fulfill its social responsibilities. On the other hand, the system responsibility can not only be linked to internal target groups alone and enhancing internal cohesion, but also meet the external target groups, enhance the reputation and influence of CX Cooperative, and bring benefits to CX Cooperative (see

Table 3).

3.3.4. Differentiation

Conditions Analysis

By the end of the maturity phase of CX Cooperative, at the end of 2018, the number of members increased to 436, the number of swarms reached 90,000, the annual production capacity of bee products reached 4000 tons, and the annual output value reached 60 million yuan. CX Cooperative became the Top-100 Apiculture Cooperative of China. A series of achievements made by CX Cooperative laid the foundation for its horizontal expansion. Since 2019, the business scope of CX Cooperative has expanded from a single bee product field to a large agricultural field including bee products, specialty fruits, etc. CX Cooperative entered the stage of re-development through horizontal expansion. Due to its good operational capability and high attention, CX Cooperative still actively fulfills its system responsibilities.

Social Responsibility Activities

In the re-development phase, CX Cooperative still maintains the social responsibility to the target group mentioned in the previous article. However, in some major events, CX Cooperative’s social responsibility performance is particularly prominent.

At the beginning of 2020, the 2019-nCoV swept the world, which also had a huge impact on the beekeeping industry. In order to help members tide over the difficulties, CX Cooperative began to send necessary supplies to members. “We sent the necessary production materials, beekeeping equipment, masks and other materials to members across the country by express”, said Wang Shun, who is the founder of CX Cooperative. Finally, CX Cooperative mailed more than 2000 masks and hundreds of beekeeping equipment to its members for free. CX Cooperative also actively helped the government fight the epidemic, and successively donated more than 5000 masks to the governments of Sangyuan Town, Tiantaishan Town, and other towns. In addition, CX Cooperative also used its own sales platform to help ordinary farmers sell citrus and other fruits in response to the low sales of agricultural products caused by the epidemic. As Wang Shun said, in the face of the epidemic, CX Cooperative should fulfill its social responsibilities, give back to society and help overcome the difficulties together.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

In this article, we construct a “life cycle-cooperative social responsibility framework (LC-CoopSRF)”, hoping to provide references for cooperatives to fulfill their social responsibilities. In “LC-CoopSRF”, we divide the cooperative’s life cycle into four phases, i.e., establishment, growth, maturity, and differentiation, and distinguish four classifications of the cooperative social responsibility, i.e., bottom-line responsibility, internal responsibility, external responsibility, and system responsibility. Based on the consideration of operational capability and ethical expectations, we believe that cooperatives concentrate on fulfilling their bottom-line responsibilities during the establishment phase, and the target group is the members. In the growth phase, cooperatives’ social responsibilities are called internal responsibilities, and the target groups mainly include members, employees, partners, animals, etc. In the maturity phase, cooperatives have the ability to fulfill social responsibilities to both internal and external target groups including members, employees, governments, communities, the natural environment, and consumers. We call this system responsibility. In the differentiation phase, cooperatives may exit or re-develop. If the cooperative chooses to exit, merge, or restructure, it will naturally no longer fulfill its social responsibilities, which we call the fading responsibility. But if the cooperative enters successful re-development phase, it will still fulfill its system responsibilities. We take CX Cooperative as a case into the “LC-CoopSRF” for analysis, and believe that the framework has practical significance and operability for encouraging cooperatives to fulfill their social responsibilities and achieve success.

Cooperatives should of course fulfill social responsibility, but in reality, there are always two specific contradictions in cooperative social responsibility. On the one hand, the cooperatives often pay more attention to their short-term benefits. Coupled with the lack of legal constraints, they tend to avoid spending money or energy to fulfill their social responsibilities. On the other hand, the society expects cooperatives to be more socially responsible but ignores the characteristics of cooperative’s life cycle and its changing ability to act in a socially responsible way. The “LC-CoopSRF” and the practice of CX Cooperative prove that the enhancement of cooperative social responsibility and the stable development of cooperatives go hand in hand. According to the characteristics of the life cycle, CX Cooperative adopts a gradually increasing approach to its social responsibility, which contributes to its sustainable development. This will also shed light on the behavior of other cooperatives.

In this article, members are the only target groups of social responsibility throughout the “LC-CoopSRF”, which also reflects the importance of the members to cooperatives. The practice of CX Cooperative conveyed that the fulfillment of social responsibilities to members should be the focus and bottom line of cooperatives. In addition to this, giving members humanistic care beyond the basic services has been an important reason for the successful development of CX Cooperative.

In addition, through the “LC-CoopSRF” and case analysis of CX Cooperative, we have further clarified the importance of cooperative social responsibility. From a micro perspective, cooperative social responsibility and sustainable development interact and promote each other. On the one hand, by fulfilling social responsibilities to internal target groups, CX Cooperative strengthened internal cohesion and maintained the health and efficiency of internal operations. By fulfilling social responsibilities to external parties, CX Cooperative improved its reputation and social influence, which has brought new business opportunities to CX Cooperative [

29]. On the other hand, as CX Cooperative entered a later stage of the life cycle, CX Cooperative was also willing to invest more funds and adopt more diversified methods to fulfill its social responsibilities. CX Cooperative fulfilled its social responsibilities step by step in accordance with its life cycle, which also made the development sustainable.

From a macro perspective, we found that the social responsibilities fulfilled by CX Cooperative were in great agreement with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. For example, the CX Cooperative contributes to “No Poverty” by guiding poor people to develop beekeeping. In order to achieve the goal of “Responsible Consumption and Production”, CX Cooperative established an electronic traceability information management system and a quality guarantee deposit system [

24], and repeatedly raised product testing standards. In order to increase people’s attention to “Life on Land”, especially insects such as bees, CX Cooperative organized popular science events every year and actively improves the welfare of bees. The series of social responsibilities fulfilled by the CX Cooperative to members and employees are conducive to the realization of the goal of “Decent Work and Economic Growth.” In fact, the realization of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals requires changes in business attitudes and behaviors. In China, every village has a cooperative [

38]. Therefore, for China’s vast rural areas, successful cooperatives are important commercial carriers to achieve Sustainable Development Goals.

Although the framework provides a feasible model of social responsibility for cooperatives, it is mainly applied to traditional cooperatives that are independently united by farmers. In China, more and more emerging cooperatives are established under the leadership of the government or enterprises. These cooperatives have been placed with high ethical expectations since their establishment. Because they are endorsed by the government or enterprises, they can perform their social responsibilities well from the establishment, without having to consider the limitations of their operating capabilities.

Moreover, it is an unquestionable topic that social responsibility is conducive to the sustainable development of cooperatives. However, do cooperatives that have fulfilled their social responsibilities necessarily have a longer life cycle, or do cooperatives that have a shorter life cycle fail to fulfill their social responsibilities? The answer is uncertain. Solving this research problem requires larger datasets or at least multiple case studies, and therefore it needs for further investigation. This article only provides a feasible model for cooperative social responsibility through the “LC-CoopSRF”, and provides a case study of the successful CX Cooperative. Therefore, the results cannot be generalized, but they provide an example of a cooperative’s successful development path. Its good practices might be transferrable to other cooperatives.