An Introduction to Aboriginal Fishing Cultures and Legacies in Seafood Sustainability

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Aims and Article Structure

3. Literature Search

4. Dreamtime/Dreaming

5. Community Structure

- Ours is the place where the mountains cohabit with the heights

- The eagle hawks and wallabies are happy

- Ours are the boomerangs and waddies, they are like Snakes lying asleep

- The kangaroos dance on the grass to smooth it down

- Ours is the head of the fish in the water

- The sweet honeycomb, the nectar inside the wooden bowl

- Ours are the splendid and beautiful young women [15].

6. Fishing Economic Currency

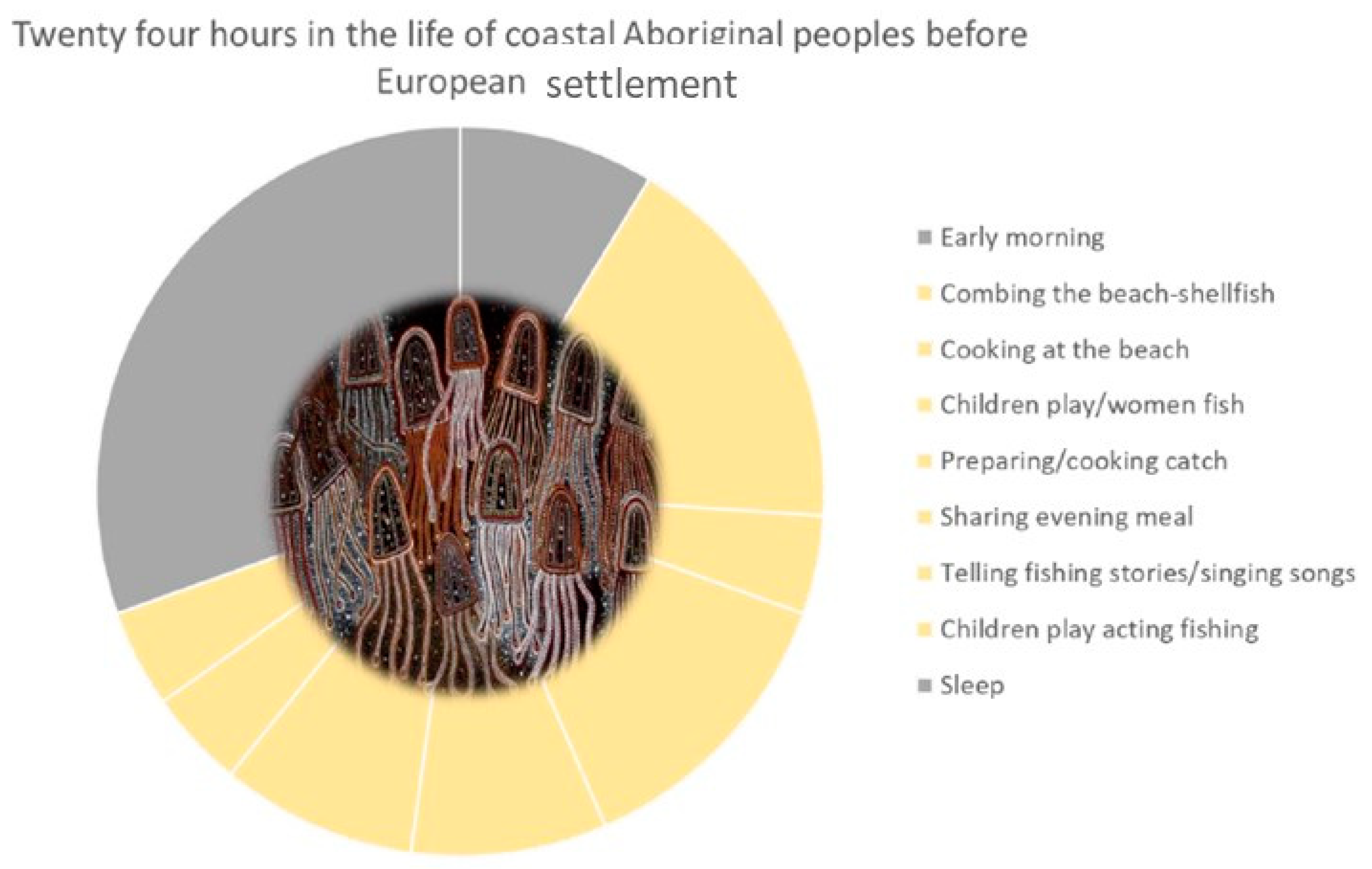

7. Fishing Culture

8. The Right to Fish

9. Early Records of Seafood Resources

10. A Cultural Imperative

11. Restrictive Government Fishing Policies

12. Sea/Saltwater Country and the Inclusion of Traditional Knowledge

13. Discussion

14. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Ethical standards

References

- Garcia, S.M.; Rosenberg, A.A. Food security and marine capture fisheries: Characteristics, trends, drivers and future perspectives. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 2869–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2008. 2009. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i0250e.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2015).

- Palmer, L. Fishing lifestyles: ‘Territorians’, traditional owners and the management of recreational fishing in Kakadu National Park. Aust. Geogr. Stud. 2004, 42, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Skiadas, P.; Lascaratos, J. Dietetics in ancient Greek philosophy: Plato’s concepts of healthy diet. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 55, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Béné, C.; Arthur, R.; Norbury, H.; Allison, E.H.; Beveridge, M.; Bush, S.; Campling, L.; Leschen, W.; Little, D.; Squires, D. Contribution of fisheries and aquaculture to food security and poverty reduction: Assessing the current evidence. World Dev. 2016, 79, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asche, F.; Bellemare, M.F.; Roheim, C.; Smith, M.D.; Tveteras, S. Fair enough? Food security and the international trade of seafood. World Dev. 2015, 67, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilson, L.L.; Goldberg, C.B. Editors’ comment: So, what is a conceptual paper? Group Organ. Manag. 2015, 40, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Korff, J. What is Aboriginal Spirituality? Available online: https://www.creativespirits.info/aboriginalculture/spirituality/what-is-aboriginal-spirituality (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Mudrooroo. Us Mob: History, Culture, Struggle: An Introduction to Indigenous Australia; Angus & Robertson: Sydney, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Randall, B. Songman: The Story of an Aboriginal Elder of Uluru; ABC Books for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation: Sydney, Australia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, C. ‘Dreamtime’ and ‘The Dreaming’: An introduction. 2014. Available online: https://theconversation.com/dreamtime-and-the-dreaming-an-introduction-20833 (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Faulstich, P. Mapping the Mythological Landscape: An Aboriginal Way of Being-in-the-World. Ethics Place Environ. 1998, 1, 197–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A. Aboriginal Women’s Fishing in New South Wales: A Thematic History; Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water NSW: Sydney, Australia, 2010; pp. 1–58. [Google Scholar]

- Cruse, B. Mutton Fish: The Surviving Culture of Aboriginal People and Abalone on the South Coast of New South Wales; Aboriginal Studies Press: Canberra, Australia, 2005; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wafer, J.; Turpin, M. Recirculating Songs: Revitalising the Singing Practices of Indigenous Australia; Wafer, J., Turpin, M., Eds.; Asia-Pacific Linguistics: Canberra, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, P.A.; Jones, D.S. Aboriginal Culture and Food-Landscape Relationships in Australia: Indigenous Knowledge for Country and Landscape. In Routledge Handbook of Landscape and Food; Zeunert, J., Waterman, T., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, R.J. Aboriginal Habitat and Economy. Master’s Thesis, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia, June 1967; pp. 1–296. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, J. An Historical Journal of the Transactions at Port Jackson and Norfolk Island; University of Sydney Library: Sydney, Australia, 2003; pp. 1–395. [Google Scholar]

- Lampert, R.J.; Hughes, P.J. Sea level change and Aboriginal coastal adaptations in southern New South Wales. Archaeol. Phys. Anthropol. Ocean. 1974, 9, 226–235. [Google Scholar]

- Bowdler, S. Bass Point: The Excavation of a South-East Australian Shell Midden Showing Cultural and Economic Change. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Lampert, R.J. An excavation at Durras North, New South Wales. Archaeol. Phys. Anthropol. Ocean. 1966, 1, 83–118. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, W.E. Food: Its search, capture, and preparation. In The Queensland Aborigines; MacIntyre, K.F., Ed.; Hesperian Press: Perth, Australia, 1901; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Outback Dreaming. This is a Story About a Great Southern Land—Called Australia. Available online: https://outbackdreaming938059841.wordpress.com/2019/10/13/this-is-a-story-about-a-great-southern-land-called-australia/ (accessed on 10 February 2020).

- Lohoar, S.; Butera, N.; Kennedy, E. Strengths of Australian Aboriginal Cultural Practices in Family Life and Child Rearing; CFCA Paper No. 25; Australian Institute of Family Studies: Melbourne, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stubington, J. North Australian Aboriginal Music: For the Promotion and Enjoyment of Traditional Arnhem Land Music. Available online: http://www.manikay.com/library/north_australian_music.shtml (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- Graham, M. Some thoughts about the philosophical underpinnings of Aboriginal worldviews. Worldviews: Glob. Relig. Cult. Ecol. 1999, 3, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards-Vandenhoek, S. This my Country, I’m Painting Here: The role of social practice art and participatory design in building resilience and place-making in the Warmun Aboriginal Community, Kimberley, Western Australia. In Proceedings of the ACUADS Conference 2015: Art and Design Education in the Global 24/7, Adelaide, Australia, 24–25 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, D.; Schilling, K.; Dargin, L. Aboriginal Women’s Heritage: Brungle & Tumut; Department of Environment and Conservation, NSW: Sydney, Australia, 2006; pp. 1–116. [Google Scholar]

- Castle, R.; Hagan, J. Settlers and the State: The Creation of an Aboriginal Workforce in Australia. Aborig. Hist. 1998, 22, 24–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M. For a Labourer Worthy of His Hire: Aboriginal Economic Responses to Colonisation in the Shoalhaven and Illawarra, 1770–1900. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Canberra, Canberra, Australia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, C. Aborigines and tin mining in north Queensland: A case study in the anthropology of contact history. Mankind 1983, 13, 473–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polidor, A.; Tindall, A. McArthur River. Available online: https://sacredland.org/mcarthur-river-australia/ (accessed on 2 November 2019).

- Young, A. McArthur River mine: The making of an environmental catastrophe. Aust. Environ. Law Dig. 2015, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kerins, S.; Jordan, K. Mining Giants, Indigenous Peoples and Art: Challenging Settler Colonialism in Northern Australia Through Story Painting. In Environmental Impacts of Transnational Corporations in the Global South; Cooney, P., Sacher, W., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingely, UK, 2018; pp. 35–71. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, B. A survey of traditional south-eastern Australian Indigenous music. In Recirculating Songs: Revitalising the Singing Practices of Indigenous Australia; Wafer, J., Turpin, M., Eds.; Asia-Pacific Linguistics: Canberra, Australia, 2017; pp. 146–178. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner, A. A study of aboriginal fisheries in northern New South Wales, Australia. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2000, 5, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Productivity Commission Draft Report—Marine Fisheries and Aquaculture; Marine Fisheries and Aquaculture Productivity Commission: Canberra, Australia, 2016; pp. 1–6.

- ALRC. Recognition of Aboriginal Customary Laws; Australian Law Reform Council: Canberra, Australia, 1986; pp. 4–737.

- Glenelg, C.G. Historical Records of Australia; Bourke, R., Ed.; Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament: Sydney, Australia, 1837. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, J. Report by Grey on the Method for Promoting the Civilization of Aborigines. Historical Records of Australia, Gipps, G., Ed.; Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament: Sydney, Australia, 1840. [Google Scholar]

- Nettelbeck, A. Queen Victoria’s Aboriginal subjects: A late colonial Australian case study. In Changing the Victorian Subject; Tonkin, M., Treagus, M., Sey, M., Rosa, S.C.-D., Eds.; University of Adelaide Press: Adelaide, Australia, 2014; pp. 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Victoria. Twelfth Report of the Board for the Protection of the Aborigines in the Colony of Victoria. Available online: https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/vufind/Record/89590 (accessed on 15 December 2019).

- Frijlink, S.D.; Lyle, J.M. Establishing Historical Baselines for Key Recreational and Commercial Fish Stocks in Tasmania; Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, University of Tasmania: Hobart, Australia, 2013; pp. 1–119. [Google Scholar]

- Favenc, E. The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Explorers of Australia and their Life-work. In The Explorers of Australia and Their Life-Work; Favenc, E., Ed.; The Project Gutenberg (Ebook), 2004; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, T.; Doran, N. Astacopsis gouldi. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. e.T2190A9337732. Available online: https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-3.RLTS.T2190A9337732.en (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Collins, D.E. An Account of the English colony in New South Wales; Cadell, T., Davies, W., Eds.; The Strand: London, UK, 1798; pp. 1–617. [Google Scholar]

- Ogilby, J. Edible Fishes and Crustaceans of New South Wales; Charles Potter, Government Printer: Sydney, Australia, 1893; pp. 1–326. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, J.; Hughes, J.; McAllister, J.; Lyle, J.; MacDonald, C. Australian Salmon (Arripis trutta): Population Structure, Reproduction, Diet and Composition of Commercial and Recreational Catches; Industry & Investment NSW: Cronulla, Australia, 2011; pp. 1–259. [Google Scholar]

- Oxley, J. Journals of Two Expeditions into the Interior of New South Wales: Undertaken by order of the British Government in the years 1817–18; John Murray: London, UK, 1820; p. 408. [Google Scholar]

- Bennet, G. Wanderings in New South Wales, Batavia, Pedir Coast, Singapore, and China: Being the Journal of a Naturalist in Those Countries, During 1832, 1833, and 1834; Richard Bentley: London, UK, 1834; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Rowland, S.J. Overview of the history, fishery, biology and aquaculture of Murray cod (Maccullochella peelii peelii). In Statement, Recommendations, and Supporting Papers, Proceedings of the Management of Murray Cod in the Murray-Darling Basin Workshop, Canberra, Australia, 3–4 June 2004; Murray-Darling Basin Commission: Grafton, Australia, 2004; pp. 38–61. [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan, D.; Zampatti, B.; Lintermans, M.; Koehn, J.; Butler, G.; Brooks, S. Maccullochella peelii. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: E.T12576A103325360. Available online: https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T12576A103325360.en (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- NSW Government. NSW Commercial Abalone Draft Fishery Management Strategy: Assessment of Impacts on Heritage and Indigenous Issues; Umwelt (Australia) Pty. Ltd.: Teralba, Australia, 2005; pp. 1–93.

- Wright, P. Submission to Phase 2 of the Review of the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) ACT 2006 (CTH); Wyatt, H.K., Ed.; Law Council of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2020; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield, S. Status of Australian Abalone Stocks (P. 3). In Abalone Assessment and Management: What Have We Learned, What Are the Gaps and Where Can We Do Better, Proceedings of the Workshop Venue, Melbourne, Australia, 7–8 March 2019; Fisheries Research & Development Corporation and Abalone Council of Australia: Melbourne, Australia, 2019; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- NSW Government. Saltwater Bag and Size Limits. Available online: https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/fishing/recreational/fishing-rules-and-regs/saltwater-bag-and-size-limits (accessed on 15 December 2019).

- McKenzie, R.; Montgomery, S.S. A Preliminary Survey of Pipis (Donax deltoides) on the New South Wales South Coast; Department of Primary Industry NWS: Orange, Australia, 2012; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Murray-Jones, S.; Steffe, A.S. A comparison between the commercial and recreational fisheries of the surf clam, Donax deltoides. Fish. Res. 2000, 44, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Primary Industry. Pipis. Available online: https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/fishing/closures/general-closures/pipis (accessed on 14 December 2019).

- NSW Government. Fisheries Management (General) Regulation 2010; No. 475; New South Wales Government: New South Wales, Australia, 2010; Volume Part 16, Division 3, Clause 277.

- DAF. Closed Seasons in Tidal Waters. Available online: https://www.daf.qld.gov.au/business-priorities/fisheries/recreational/closed-seasons-waters/tidal-waters (accessed on 15 June 2019).

- DAF. Closed Waters—Tidal Waters. Available online: https://www.daf.qld.gov.au/business-priorities/fisheries/recreational/closed-seasons-waters/waters-tidal (accessed on 15 June 2019).

- DAF. Closed Waters in Freshwater Areas. Available online: https://www.daf.qld.gov.au/business-priorities/fisheries/recreational/closed-seasons-waters/freshwater-areas (accessed on 15 June 2019).

- DAF. Recreational Closed Seasons Fresh Water. Available online: https://www.daf.qld.gov.au/business-priorities/fisheries/recreational/closed-seasons-waters/fresh-waters (accessed on 15 June 2019).

- Smyth, D.; Isherwood, M. Protecting sea country: Indigenous people and marine protected areas in Australia. In Big, Bold and Blue: Lessons from Australia’s Marine Protected Areas; Fitzsimons, J., Wescott, G., Eds.; CSIRO Publishing: Clayton, Australia, 2016; pp. 307–325. [Google Scholar]

- Rist, P.; Rassip, W.; Yunupingu, D.; Wearne, J.; Gould, J.; Dulfer-Hyams, M.; Bock, E.; Smyth, D. Indigenous protected areas in Sea Country: Indigenous-driven collaborative marine protected areas in Australia. Aquat. Conserv: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2019, 29, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smyth, D. Fishing for Recognition: The search for an Indigenous fisheries policy in Australia. Indig. Law Bull. 2000, 4, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- NIAA. Indigenous Protected Areas Map February 2020. Available online: https://www.niaa.gov.au/sites/default/files/files/ia/IEB/ipa-national-map-feb-20.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Smyth, D. Guidelines for Country-Based Planning; Department of Environment and Resource Management: Brisbane, Australia, 2012; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Dhimurru Aboriginal Corporation. Dhimurru IPA Sea Country Management Plan. Available online: http://www.dhimurru.com.au/sea-country-management.html (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Heathcote, G. ‘Monstrous’: Indigenous Rangers’ Struggle Against the Plastic Ruining Arnhem Land Beaches. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/may/15/monstrous-indigenous-rangers-struggle-against-the-plastic-ruining-arnhem-land-beaches (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Cullen-Unsworth, L.C.; Hill, R.; Butler, J.R.; Wallace, M. A research process for integrating Indigenous and scientific knowledge in cultural landscapes: Principles and determinants of success in the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area, Australia. Geogr. J. 2012, 178, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, D.G.; Hamilton, R.B.; Kuriansky, J. Ecopsychology: Advances from the Intersection of Psychology and Environmental Protection; Praeger: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 1–283. [Google Scholar]

- Balme, J.; O’Connor, S.; Maloney, T.; Vannieuwenhuyse, D.; Aplin, K.; Dilkes-Hall, I.E. Long-term occupation on the edge of the desert: Riwi Cave in the southern Kimberley, Western Australia. Archaeol. Oceania 2019, 54, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clarkson, C.; Marwick, B.; Wallis, L.A.; Fullagar, R.; Jacobs, Z. Buried Tools and Pigments Tell a New History of Humans in Australia for 65,000 Years. Available online: https://theconversation.com/buried-tools-and-pigments-tell-a-new-history-of-humans-in-australia-for-65-000-years-81021 (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Rowland, S.J. Hormone-induced spawning of the Australian freshwater fish Murray cod, Maccullochella peeli (Mitchell)(Percichthyidae). Aquaculture 1988, 70, 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, B.W.; Bowman, D.M.; Burney, D.A.; Flannery, T.F.; Gagan, M.K.; Gillespie, R.; Johnson, C.N.; Kershaw, P.; Magee, J.W.; Martin, P.S. Would the Australian megafauna have become extinct if humans had never colonised the continent? Comments on" A review of the evidence for a human role in the extinction of Australian megafauna and an alternative explanation" by S. Wroe and J. Field. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2007, 26, 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.H.; Fogel, M.L.; Magee, J.W.; Gagan, M.K.; Clarke, S.J.; Johnson, B.J. Ecosystem collapse in Pleistocene Australia and a human role in megafaunal extinction. Science 2005, 309, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westaway, M.C.; Olley, J.; Grün, R. At least 17,000 years of coexistence: Modern humans and megafauna at the Willandra Lakes, South-Eastern Australia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2017, 157, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, B. Dark Emu: Aboriginal Australia and the Birth of Sgriculture; Magabala Books Aboriginal Corporation: Broome, Australia, 2018; pp. 1–240. [Google Scholar]

- Woinarski, J.C.Z.; Braby, M.F.; Burbidge, A.A.; Coates, D.; Garnett, S.T.; Fensham, R.J.; Legge, S.M.; McKenzie, N.L.; Silcock, J.L.; Murphy, B.P. Reading the black book: The number, timing, distribution and causes of listed extinctions in Australia. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 239, 108261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2016. Contributing to food security and nutrition for all. 2016. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i5555e.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2019).

- de Souza, M.C.; Lem, A.; Vasconcellos, M. Overfishing, Overfished Stocks, and the Current WTO Negotiations on Fisheries Subsidies; ICTSD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–83. [Google Scholar]

- Hossen, S.; Wassens, S.; Shamsi, S. Integrative species delimitation and community structure of nematodes in three species of Australian flathead fishes (Scorpaeniformes: Platycephalidae). Parasitol. Res. 2020, submitted. [Google Scholar]

- RLS. Reef Life Survey. Available online: https://reeflifesurvey.com/about-rls/ (accessed on 7 March 2020).

- Edgar, G.; Ward, T.; Stuart-Smith, R. Rapid declines across Australian fishery stocks indicate global sustainability targets will not be achieved without an expanded network of ‘no-fishing’ reserves. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2018, 28, 1337–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, T.; Lloret, J. Biological and Ecological Impacts Derived from Recreational Fishing in Mediterranean Coastal Areas. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2014, 22, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlgorm, A.; Pepperell, J. An Economic Survey of the Recreational Fishing Charter Boat Industry in NSW; A report to the NSW Department of Primary Industries; Dominion Consulting Pty. Ltd.: Towradgi, Australia, 2014; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, C.; Kennelly, S. Evaluation of observer-and industry-based catch data in a recreational charter fishery. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2017, 24, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, M.J. Munda-Gutta Kulliwari, Dreamtime Kullilla-Art. Available online: https://www.kullillaart.com.au/dreamtime-stories/The-Guardian-of-the-Rivers (accessed on 15 December 2019).

- ANON. Thukeri (Bream). Available online: http://dreamtime.net.au/thukeri/ (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Cooke, S.J.; Suski, C.D. Do we need species-specific guidelines for catch-and-release recreational angling to effectively conserve diverse fishery resources? Biodivers. Conserv. 2005, 14, 1195–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muoneke, M.I.; Childress, W.M. Hooking mortality: A review for recreational fisheries. Rev. Fish. Sci. 1994, 2, 123–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouja, P.M.; Dewailly, É.; Blanchet, C.; Community, B. Fat, fishing patterns, and health among the Bardi People of North Western Australia. Lipids 2003, 38, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, S.; Suchet-Pearson, S.; Lloyd, K.; Burarrwanga, L.L.; Burarrwanga, D. ‘That means the fish are fat’: Sharing experiences of animals through Indigenous-owned tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2009, 12, 505–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichardt, D. Ngurunderi and the Murray cod: Glimpses into Australian Aboriginal anthropology and cosmology from a white fella’s viewpoint: Christian Faith and the Earth. Scr. Int. J. Bible Relig. Theol. South. Afr. 2012, 111, 408–421. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; Opened for Signature 16 December 1966 UNTS 2200A (XXI)/(Entered Into Force 3 January 1976), Art 27.; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 1976. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shamsi, S.; Williams, M.; Mansourian, Y. An Introduction to Aboriginal Fishing Cultures and Legacies in Seafood Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9724. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229724

Shamsi S, Williams M, Mansourian Y. An Introduction to Aboriginal Fishing Cultures and Legacies in Seafood Sustainability. Sustainability. 2020; 12(22):9724. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229724

Chicago/Turabian StyleShamsi, Shokoofeh, Michelle Williams, and Yazdan Mansourian. 2020. "An Introduction to Aboriginal Fishing Cultures and Legacies in Seafood Sustainability" Sustainability 12, no. 22: 9724. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229724

APA StyleShamsi, S., Williams, M., & Mansourian, Y. (2020). An Introduction to Aboriginal Fishing Cultures and Legacies in Seafood Sustainability. Sustainability, 12(22), 9724. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229724