Abstract

In the last decade, the fossil fuel divestment (FFD) movement has emerged as a key component of an international grassroots mobilization for climate justice. Using a text analysis of Facebook pages for 144 campaigns at higher education institutions (HEIs), this article presents an overview and analysis of the characteristics of the higher education (HE) FFD movement in the US. The results indicate that campaigns occur at a wide array of HEIs, concentrated on the east and west coasts. Primarily student led, campaigns set broad goals for divestment, while reinvestment is often a less clearly defined objective. Campaigns incorporate a mixture of environmental, social, and economic arguments into their messaging. Justice is a common theme, used often in a broad context rather than towards specific populations or communities impacted by climate change or other social issues. These insights contribute to the understanding of the HE FFD movement as ten years of campus organizing approaches. In particular, this study illustrates how the movement is pushing sustainability and climate action in HE and in broader society towards a greater focus on systemic change and social justice through campaigns’ hardline stance against fossil fuels and climate justice orientation.

1. Introduction

Replacing fossil fuels with renewable energy will be a critical strategy for keeping global warming below internationally recognized targets of 1.5 degrees Celsius and two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels [1,2,3]. Governments have recognized the need for urgent efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions yet have failed to implement strategies that explicitly challenge continued fossil fuel extraction and production [4]. Instead, focus has often been on market-based solutions like carbon trading and the promise of unproven technological fixes like carbon capture and storage, approaches which uphold current economic and political structures [5,6,7]. International climate accords, including the Paris Agreement, while establishing ambitious goals for transnational efforts to curb emissions, have ignored the issue of directly limiting fossil fuel extraction and production in favor of allowing countries to reduce emissions in ways that are less disruptive to the economic status quo like purchasing carbon offsets from emissions-reducing projects in developing countries [8,9,10].

Faced with global crises like climate change, higher education institutions (HEIs) have the potential to act as agents of change to influence society towards greater sustainability [11]. Many HEIs have sought to take up a leadership role in the climate crisis, for example through integrating climate change education into curricula, climate change research, efforts to reduce campus greenhouse gas emissions, and incorporating climate change into strategic planning through commitments like the American College and University Presidents’ Climate Commitment (ACUPCC) [12,13,14,15]. However, sustainability discourse and action in higher education (HE) has often embodied a reformist, green economy approach that fails to challenge the root causes of crises like climate change [4,16,17].

At the institution level, strategies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions are internally-focused and incremental. For example, signatories of the ACUPCC have committed to becoming carbon neutral, a goal that many HEIs do not anticipate achieving until near-midcentury and is understood to likely require the purchase of carbon offsets which have questionable benefits for the climate due to challenges of ensuring that funds go towards projects that result in legitimate emissions reductions [18]. Students at HEIs are often engaged in sustainability initiatives narrowly focused on individual behavior change, such as addressing personal carbon footprints [17,19]. Meanwhile, education for sustainable development has broadly presented an uncritical, often idealistic view of sustainable development that neglects to question hegemonic structures underpinning many sustainability problems, like neoliberalism, globalization, and the economic growth imperative [20,21].

This approach to sustainability in HE not only misframes the climate crisis as a problem that can be solved without radical economic and political change, but also often presents climate change independent of intersectional issues of environmental justice [4,16]. At the heart of these issues may be HE’s increasing alignment with a neoliberal agenda which has led HEIs to have an increased focus on institutional finances and competition with other HEIs [22,23], presenting a challenge to the ability of sustainability in HE to incite transition away from current unsustainable paradigms [4,24].

Within the last ten years, the HE fossil fuel divestment (FFD) movement has emerged as a challenge to mainstream climate action and sustainability in HE and broader society by asking HEIs to explicitly cut ties with the fossil fuel industry through divestment of financial holdings in fossil fuel companies. The movement was initiated in 2011 when students at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania started a campaign to persuade their school to divest from coal companies in solidarity with Appalachian communities impacted by mountaintop removal mining [25,26]. Several other coal divestment campaigns were launched at US HEIs in 2011 and more campaigns soon followed with the call expanding to divestment from all fossil fuels [27].

In 2012, Bill McKibben published the popular article “Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math” and embarked on the Do the Math Tour with his climate advocacy organization 350.org, promoting institutional FFD [17,28]. McKibben and 350.org, along with other organizations, subsequently worked to support the development of hundreds of FFD campaigns at HEIs in the US and internationally [17,29,30]. Though campaigns at some HEIs were met with stern rejection by administrators, FFD commitments from HEIs soon began rolling in [17]. FFD also soon expanded beyond HE to become a global movement of institutions, including faith-based organizations, philanthropic foundations, cities, and pension funds, committing to not invest in fossil fuels [26].

In 2017, the major organizations promoting HE FFD in the US, including 350.org, scaled back on their support to HE campaigns and the movement on US campuses began to lose steam. To fill the gap, non-profit Better Future Project launched the program Divest Ed in 2018, which aimed to provide coaching and community to student FFD campaigns across the country [31]. Supported by Divest Ed, the US HE FFD movement saw a resurgent wave of escalation and successes in 2019 and early 2020, including notable commitments from the University of California System and Georgetown University, and a national day of action in February 2020 [32]. There are currently over 50 US HEIs that have committed to at least partial divestment from fossil fuels, ranging from small liberal arts colleges to large public university systems [33,34]. Signs point to the movement continuing with its momentum despite challenges presented by the COVID-19 pandemic, with many campaigns turning to online tactics to continue organizing and putting pressure on administrators [35].

FFD diverges from conventional reformist approaches to climate action and sustainability by explicitly seeking to put an end to continued fossil fuel extraction and production. By using divestment to take a moral stand against fossil fuel companies, the main aim of the movement is to create a social stigma against the fossil fuel industry, thereby generating political and economic pressure for a societal transition away from fossil fuels [4,16,17]. This strategy has precedent in previous divestment movements, including those against companies doing business in apartheid South Africa and the tobacco industry [36]. FFD therefore politicizes sustainability to achieve systemic change through collective action, a rebuke of mainstream greening approaches to sustainability which focus on incremental and individualized change [16,17].

Divestment also entails the complementary step of reinvestment, in which divested money is reallocated towards more desirable investments. Calls for sustainable reinvestment are often made by HE FFD activists. This may take the form of demands for reinvestment into “climate solutions,” such as clean and renewable energy. Some campaigns and organizations have emphasized the need for reinvestment in communities, such as funding community-owned renewable energy projects [25,37]. Divest Ed encourages campaigns to work towards reinvestment in local economies led by marginalized communities, through investment in community development financial institutions or other means, to ensure an equitable reallocation of resources [38]. However, HEIs may simply reinvest into alternative investments based on the financial needs of their portfolio, such as non-fossil fuel companies and funds that perform similarly to fossil fuel investments [4].

Unlike mainstream sustainability approaches that focus on environmental impacts of resource use, FFD is rooted in concerns for human wellbeing and social justice. The movement can be thought of as an extension of the environmental justice movement that began in the US in the 1980s with concerns over the disproportionate exposure of communities of color and low-income communities to toxic waste [16,39]. Environmental justice combines notions of environmental sustainability with social justice considerations, calling for equitable distribution of environmental risks and benefits and fair and inclusive decision-making on environmental issues. The concept of climate justice emerged naturally out of this framework [40], highlighting the disproportionate risks climate change poses to poor people, people of color, and Indigenous Peoples and the need for a “just transition” to a post-carbon economy that ensures fairness and equity in outcomes and procedural processes [41,42]. Climate justice activists have often been critical of market-based and consumerist approaches to climate mitigation, seeing them as catering to wealthy elites at the expense of vulnerable communities, and have insisted on keeping fossil fuels in the ground as a primary response [40,43]. A recent form of climate justice activism termed “Blockadia” has seen increasing resistance to fossil fuel and other extractive projects using direct action tactics and is often led by frontline communities who are at risk from these projects [44].

FFD extends climate justice concerns and demands and applies them to institutional finance in a Blockadia-style attempt to cut off the social and financial support for fossil fuels. Climate justice has been central to the narrative of the HE FFD movement, with campaigns and organizations often highlighting the disproportionate impacts of climate change and fossil fuel extraction on historically marginalized populations and seeking to show solidarity with frontline communities that bear the brunt of their impacts [4,16,17,29].

With over 1200 institutions worth more than $14 trillion now committed to FFD [33], the FFD movement has had significant global impacts. FFD has succeeded at its goal of placing a stigma on the fossil fuel industry as a key perpetrator of the climate crisis, putting fossil fuel companies on the defensive and forcing them to justify their value to the public and investors [30,45]. The movement has also begun to represent a legitimate problem for the business of the fossil fuel industry, with international fossil fuel companies like Shell and Peabody citing FFD as a major financial challenge [46]. The troubles may be particularly deep for the struggling coal industry, as Goldman Sachs notes that FFD was a key driver of the coal sector’s 60% de-rating between 2013 and 2018 [47].

Beyond its impact on the fossil fuel industry, FFD has had the broader effect of reshaping discourse on climate change and sustainable finance. As the movement emerged, it introduced the radical idea to mainstream climate change discourse that fossil fuel companies must be immediately stopped to ensure a just and livable future for the planet. Empirical research has suggested this shifted the center of public climate change discourse in the early years of the movement resulting in liberal policy ideas that were previously seen as far reaching, such as a carbon tax and carbon budget, receiving increased attention and legitimacy. Meanwhile, the radical ideas presented by the FFD movement infiltrated conventional thinking in the finance world through increased attention to concepts describing risks of high carbon investments, like stranded assets and the carbon bubble [48]. The elevated concern around investments in fossil fuels has led to changes such as the increase in funds available to investors that do not have fossil fuel holdings and the questioning of traditional notions of fiduciary duty that have focused on maximizing short-term returns [30].

Despite the importance of HEIs in the initiation and continued advancement of the FFD movement and the unique arena the HE context provides for shifting discourse on climate change and sustainability, scholarly work on FFD in HE has been limited [4,19,29]. Research has explored the movement through focus on campaigns at a limited number of HEIs [4,16,17], or has focused on narrow elements of the movement such as rationales used by divesting HEIs and the role of faculty in campaigns [49,50]. With the exception of Maina et al., (2020), who recently completed a study of all HE FFD campaigns in Canada [29], there has been little research that has explored the extent of the movement or its characteristics using data from a large portion of HEIs involved in the movement. This paper seeks to fill this gap with a focus on the US, examining the locations and types of institutions where campaigns occur, the stakeholders involved in campaigns and the goals they adopt, and the themes campaigns use in their messaging.

Presented as ten years of organizing for FFD at HEIs approaches, this study provides an overview and analysis of the US HE FFD movement. The results contribute to a better understanding of the movement’s characteristics, demands, and how it fits within the broader context of sustainability and climate change discourse and action in HE and beyond. Particularly, this study illustrates how the HE FFD movement is pushing sustainability towards a greater focus on systemic change and social justice through campaigns’ hardline stance against fossil fuels and climate justice orientation. Finally, this study offers an opportunity for critical reflection on the HE FFD movement itself and suggestions are discussed for how the movement may continue to be developed.

2. Materials and Methods

This study seeks to assess several factors that have been underexplored in the literature on the HE FFD movement in the US. First, the spatial distribution of campaigns and the type of HEIs where these campaigns occur is assessed. Second, the types of stakeholders involved in campaigns and common goals of campaigns are identified. This includes identification of campaigns’ goals for reinvestment, which has scarcely been explored in academic research. Third, common themes used in campaigns’ messaging are identified. This includes an examination of how campaigns address the notion of justice. Though climate justice has been heralded as a key tenet of the HE FFD movement [4,16,17], examination of how campaigns frame arguments around the notion of justice has been limited. This provides an important opportunity to assess the intersectionality of the movement, particularly as movements addressing race and diversity, such as Black Lives Matter and immigrants’ rights movements, have also found support from student activists at US HEIs in recent years [51].

To address the research objectives, 144 FFD campaigns at US HEIs were analyzed, using a text analysis of Facebook pages associated with these campaigns. Social media has played an increasingly important role in social movements in recent years, facilitating instant communication and information-sharing among activists and between activists and other societal stakeholders [52,53,54]. This includes student activism, which has embraced social media as a new tool for campaigning and protesting [55,56]. Other research indicates that over 80% of FFD campaigns at HEIs in North America have a Facebook page and a host of other social media platforms are commonly used by campaigns [29]. This study exploits the ubiquitous use of social media in contemporary student movements to collect and analyze data on the characteristics of FFD campaigns at US HEIs from campaign Facebook pages.

The sample was identified from records on active and inactive campaigns throughout the US provided by Divest Ed. The first phase of this study took place between May and August 2019, and sought to identify Facebook pages associated with campaigns. If a Facebook page was not listed within the records for a campaign, then an online search was conducted with the keywords “divest,” “fossil free,” and “fossil fuel divestment” along with the name of the HEI where the campaign was located. For any campaign where multiple Facebook pages were discovered, the most relevant page was selected based on criteria favoring pages with the most recent posts and pages with the most information on the campaign associated with them in their “About” section. A campaign at the authors’ home institution was excluded to maintain objectivity. This process generated a total sample of 144 FFD campaigns, each at a separate HEI. Table S1 provides a list of all HEIs with campaigns used in this study and URLs of the Facebook pages used for each campaign.

The records from Divest Ed provided general information on the HEIs, including location and public or private designation of each institution. The spatial distribution of campaigns was assessed by totaling the number within each of the U.S. Census Bureau’s nine divisions [57], a system of regionality widely used for research [58,59].

The analysis of the Facebook pages first involved extracting all the text from the “About” section for each page, which occurred between 17 January and 27 January 2020. The text for each page was then coded to identify types of stakeholders involved in campaigns, goals stated by campaigns, and themes campaigns used in their discussion of why they were organizing. Themes were organized under the three major categories of environmental, social, and economic, based on the three “pillars of sustainability” that are commonly used in the sustainability field [60,61,62].

The way that campaigns addressed justice was considered within the social category. A reference to justice was considered any direct mentions of the concept through the words “justice” or “just,” references to disproportionate harms or deprivations being imparted on particular groups of people, or references to efforts to right such disproportionate harms or deprivations. Though justice was not only considered within the environmental context, this conception of justice is tied closely to the notion of equity at the root of the environmental justice movement, that injustice occurs from an unfair distribution of environmental costs and benefits across different groups of people [40].

3. Results

3.1. US HEIs with FFD Campaigns

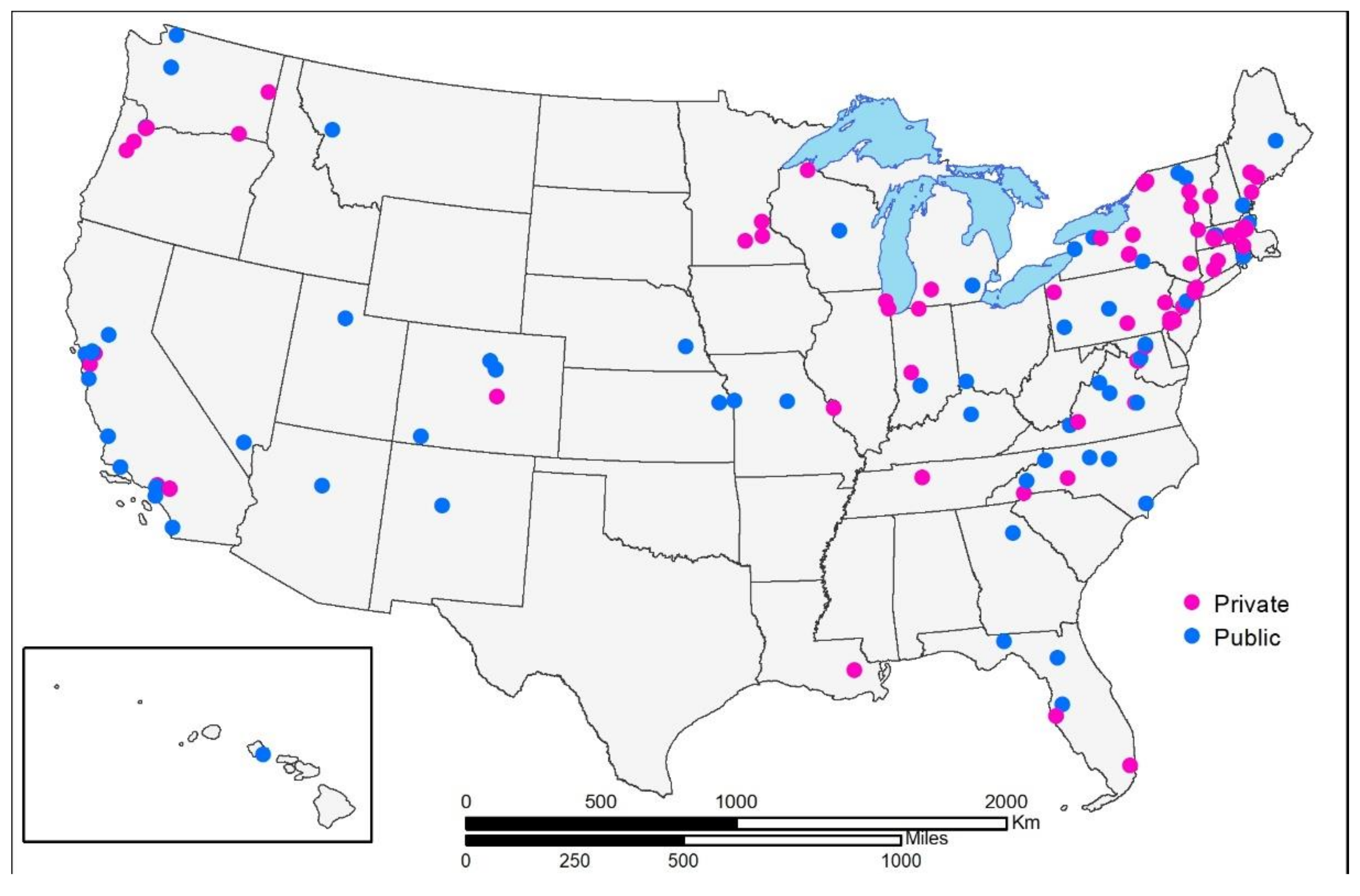

The 144 FFD campaigns in this study were located at a variety of HEIs throughout the country, from small liberal arts colleges to large research universities. Of these HEIs, 56% are private and 44% are public (Figure 1). Public higher education systems comprised 5% of the HEIs. In some cases, there were campaigns at both the campus and system level. An example is the University of California System, which committed to full divestment in 2019 after over six years of activists running both a collaborative, system-wide campaign and campaigns at the individual universities within the system [63]. This study included both the University of California system-wide campaign and campaigns at six of the universities within the system. Among other characteristics of the HEIs with campaigns in the sample, 11% are religiously affiliated, 3% are women’s colleges, and all eight Ivy League institutions were present.

Figure 1.

Location of US private and public higher education institutions (HEIs) with fossil fuel divestment (FFD) campaigns from sample of 144 campaigns. Each dot represents an HEI with a campaign, though not all HEIs are distinguishable due to clustering in some areas.

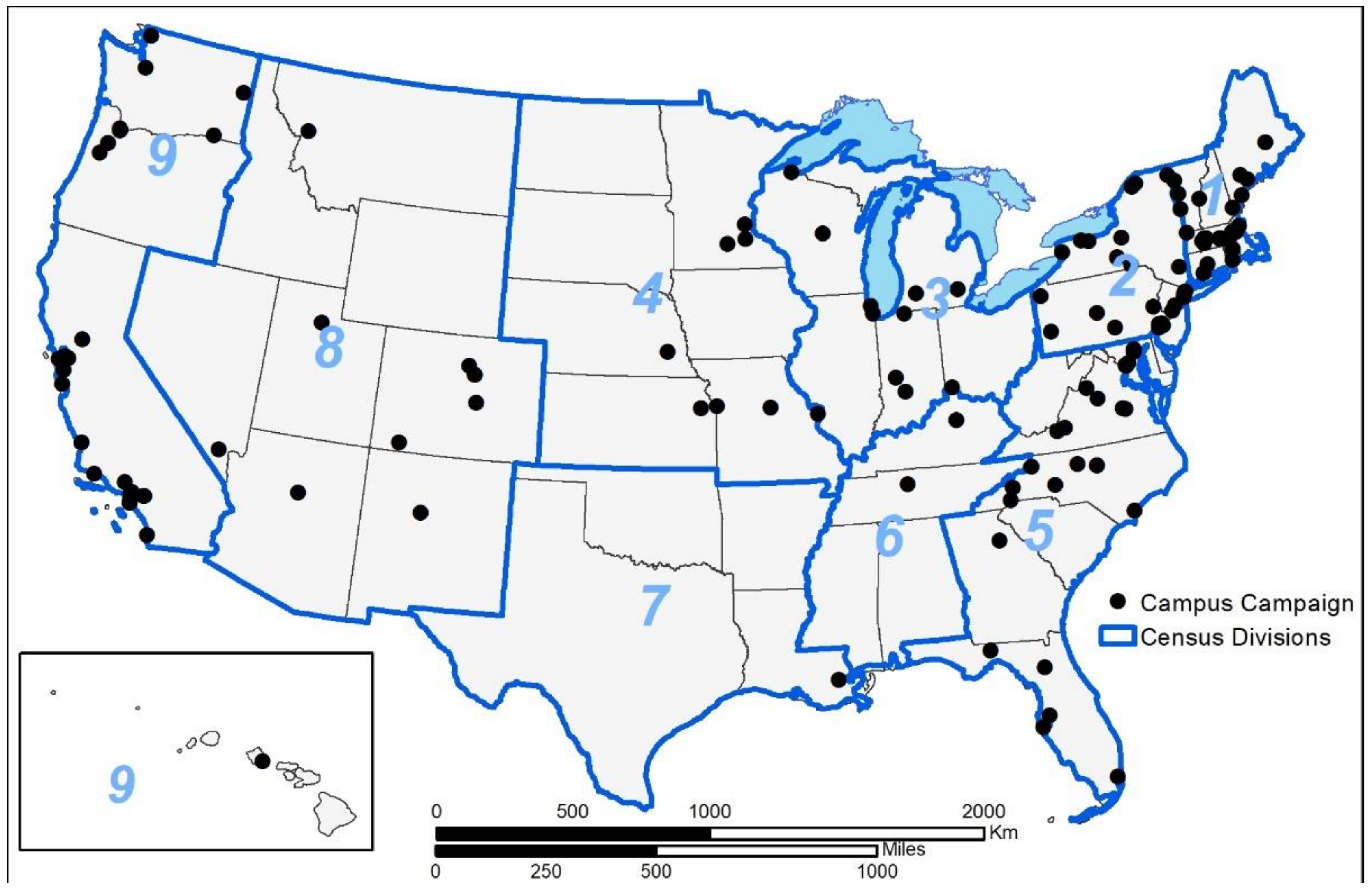

Campaigns are concentrated in the states along the east and west coasts of the US, particularly in the northeast (Table 1, Figure 2). The four divisions located along the east and west coasts (New England, Middle Atlantic, South Atlantic, and Pacific) contained 78% of campaigns in the sample. New England and Middle Atlantic, the two divisions in the northeast US, contained the two highest numbers of campaigns of any division, with a combined share of 42% of all campaigns. The two divisions comprising the south central US, East South Central and West South Central, contained the two lowest numbers of campaigns of any division, with a combined share of 2% of all campaigns.

Table 1.

Total higher education (HE) FFD campaigns per US Census Bureau division from sample of 144 campaigns. Numbers in the first column correspond with the division numbers in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of HE FFD campaigns among US Census Bureau divisions from sample of 144 campaigns. Numbers correspond with divisions listed in Table 1. Each dot represents one campaign, though not all campaigns are distinguishable due to clustering in some areas.

3.2. Campaign Stakeholders and Goals

Sixty-one percent of campaigns described types of stakeholders that were involved with their efforts in their Facebook “About” sections. Of these campaigns, 93% mentioned having students involved. The next most common stakeholder types mentioned were faculty and alumni, each mentioned by 15% of campaigns describing stakeholders. The involvement of “community members” was mentioned by 13% of campaigns describing stakeholders, though it was unclear how this was defined by each campaign. Six percent of campaigns describing stakeholders mentioned having staff from each of their HEIs involved.

The goals described by campaigns revealed some key commonalities (Table 2). In general, campaigns were broadly asking their HEIs to divest from all types of fossil fuels (coal, oil, and natural gas). Nineteen percent of campaigns specified that their HEIs should divest from the top 200 fossil fuel companies, likely in reference to the Carbon Underground 200 (CU 200) list of the top 100 coal companies and top 100 oil and gas companies, ranked by the carbon emissions potential of their reserves [64]. This list has often been used as a guide for FFD by HEIs and is considered a standard for FFD by 350.org [4,65]. Campaigns rarely extended the call for divestment to other harmful industries and investments beyond fossil fuels. Among the 3% of campaigns that did call for other types of divestment in addition to FFD, targets included the arms industry, prisons, sweatshops, and holdings in Puerto Rico’s debt. If campaigns specified whether their HEIs should divest direct investments in fossil fuel companies, indirect investments in fossil fuel companies (i.e., fossil fuel holdings tied up with other investments in externally managed funds, such as mutual funds), or both, they almost always called for both direct and indirect divestment. Campaigns commonly set a deadline by which they wanted their HEIs to complete divestment. This was most often within five years, a demand given by 23% campaigns.

Table 2.

Common goals of FFD campaigns at US HEIs. 1

Reinvestment goals were mentioned by 31% of campaigns. Campaigns tended to call generally for reinvestment into sustainable or socially just funds, solutions, or other alternatives to fossil fuel investments, without giving specific demands about which funds, companies, industries, or projects they desired their HEIs to target for reinvestment. However, 8% of campaigns specified that their HEIs should reinvest into renewable or clean energy. Only 1% of campaigns emphasized that reinvestment should be directed towards their local area or community.

Goals mentioned by campaigns were not limited solely to divestment and reinvestment. Other goals were mentioned by 24% of campaigns. The most common of these was educating the public about climate change and environmental issues, mentioned by 8% campaigns. Six percent of campaigns called for greater investment transparency or disclosure of investments by their HEIs. Some campaigns were also advocating for other climate or energy actions beyond divestment. This included 3% of campaigns that were calling for clean energy or emissions reductions on campus, and 4% of campaigns that mentioned advocating for climate action outside of their HEI, such as in state or national policy.

3.3. Themes Used in Campaign Messaging

All three of the major sustainability themes of environmental, social, and economic were commonly used by campaigns in their messaging. Environmental themes were the most common, being used by 81% of campaigns, followed by social themes, used by 62% of campaigns, then economic themes, used by 35% of campaigns. These themes were often used in combination with each other, with 30% of campaigns using all three major themes. Further exploration of themes revealed some key commonalities (Table 3).

Table 3.

Common themes used in messaging by FFD campaigns at US HEIs. 1

Sixty-nine percent of campaigns used environmental themes related to climate change. This was often in regards to the negative impacts of climate change, such as rising sea levels, worsening droughts, and increases in devastating hurricanes, on communities and society. In this way, climate change often formed the frame around which social and economic factors were discussed. Although some campaigns discussed the impacts of fossil fuels on the wellbeing of the environment, such as effects on biodiversity and ecosystem health, environmental themes were more often used to connect fossil fuels to problems affecting the wellbeing and prosperity of humans.

Social themes were a far-ranging category that included discussion on how fossil fuels impact human wellbeing and how divestment can contribute to the mitigation of these impacts. This included the effects of climate change on community wellbeing, human health, and the wellbeing of students after they graduate. Social themes often reflected a justice perspective, with 44% of campaigns using themes related to justice. Justice-related themes were frequently used directly in the context of environmental problems, namely climate change, and often described disproportionate impacts on certain groups of people, such as frontline communities.

A small percentage of campaigns made connections to broader intersectional issues of justice. For example, 9% of campaigns connected FFD to issues of racial justice. This included campaigns that cited inspiration from the South African apartheid divestment movement. Disproportionate impacts of climate change and fossil fuels on communities of color were also recognized, though only by a few campaigns. Issues of economic justice were mentioned by 5% of campaigns, for example by discussing disproportionate environmental impacts on the poor. There were also 5% of campaigns that drew connections to issues of gender and sex-based justice, stating their support for movements against gender discrimination, against sexual assault, and for the advancement of women. Despite the connections made by some campaigns to intersectional issues of justice, there were some marginalized groups that received very few mentions, including African Americans, Indigenous Peoples, immigrants, and LGBTQ+ people. Also of note, there were no campaigns that directly referenced local environmental justice issues, such as local communities impacted by fossil fuel projects or climate change.

Campaigns used economic themes to discuss both considerations for the economy as a whole and economic factors affecting their HEIs. Seventeen percent of campaigns emphasized the financial benefits of FFD to their HEIs, often making arguments about the risky nature of fossil fuel investments and that divestment could help protect their endowments from financial losses. More broadly, campaigns advocated for FFD as a means to help the economy, such as by addressing financial costs to the country from climate change and encouraging new clean energy development. Several campaigns also described FFD as an opportunity to help build a new economy centered on justice and sustainability, and move away from the extractive, inequitable economy upheld by the fossil fuel industry.

Beyond the frames of the three “pillars of sustainability,” campaigns saw sustainability itself as an important theme, with 31% of campaigns using the words “sustainability” or “sustainable.” In this context, fossil fuels and the industry behind their use are deemed as inherently unsustainable, and FFD is seen as a tool for creating a more sustainable society not reliant on them. As another overarching theme, 36% of campaigns argued that FFD was in line with the values of their HEIs. For example, campaigns expressed that higher education has a responsibility to be a leader in responding to major problems like climate change. Some campaigns also argued that FFD was in line with their HEI’s mission, religious values, or established commitment to sustainability.

4. Discussion

The results provide a window into the HE FFD movement in the US, revealing some important insights about the characteristics of campaigns that have been involved.

Fifty-six percent of campaigns in the sample are at private HEIs, including all eight of the Ivy League institutions. Analysis of US campaigns in scholarly literature have often focused on private HEIs, such as Harvard University [4,66,67], American University [16], and Pitzer College [17]. Campaigns at Ivy League HEIs have been a staple of the movement, with high profile standoffs with administrators and disruptive protests that have garnered international media attention [68,69]. However, 44% of campaigns in the sample were found to be at public HEIs. This is similar to the breakdown of all degree-granting HEIs in the US, of which 59% are private and 41% are public [70]. Campaigns at public HEIs have the potential to build multi-campus coalitions and to achieve big divestment wins when operating within a HE system, as several campaigns were found to be. The University of California System divestment was deemed historic for the university’s size and $126 billion portfolio it impacted [71]. Campaigns at such prominent institutions, however, only represent a portion of a movement occurring at a wide range of HEIs big and small.

Campaigns were found to be concentrated in the states along the east and west coasts of the US, particularly in the northeast. There are many factors that may contribute to this distribution. This includes the large number of HEIs in these areas, with 53% of all degree-granting HEIs in the US located in the Census divisions on the east and west coasts and 21% located in the divisions in the northeast [72]. The high concentration of population and social activity near the US coasts [73,74], as well as strong liberal political attitudes in the northeast and on the west coast [75,76], may be additional factors. It should also be noted that Divest Ed is based in Massachusetts, which may contribute to the number of campaigns existing in the northeast and may also bias the sample to include more campaigns in the northeast, due to the connections the program has in this region.

Though the high number of campaigns on the east and west coasts may arise naturally from such factors as high population levels and favorable political attitudes, the stark absence of campaigns elsewhere raises interesting questions about how such a distribution may impact the efficacy of the movement. For example, there are areas of the country known for heavy fossil fuel production where campaigns are largely absent. Most notable is the West South Central division, which contains a hotbed of oil and natural gas production within the states of Texas, Oklahoma, and Louisiana [77,78], yet had only one campaign in the sample. To the north, Wyoming, which accounted for 40% of US coal produced in 2018 [79], and major fracking state North Dakota both contained no campaigns in the sample [80,81]. The noticeable absence of campaigns in the south is also of note due to the fact that the southeastern US is projected to be hardest hit by many impacts of climate change, exacerbating disproportionately high poverty levels in this area [82,83,84]. If location of campaigns matters to the ability of the HE FFD movement to take on the fossil fuel industry and address the injustices of climate change, the distribution that exists does not seem to be as well poised as it could be to doing so.

Campaigns that mentioned stakeholder types overwhelmingly recognized students as being involved with their efforts. This is not surprising given HE FFD’s general acceptance as primarily a student-led movement [4,16,17,29]. However, the results shed light on the common participation of other HE stakeholders, including alumni, faculty, and staff, which has been less recognized. These stakeholders have been noted as playing important supportive roles to student campaigns. For example, faculty may serve as mentors to student campaigns or sign on to letters to administrators endorsing FFD [16,50]. Alumni may leverage their standing by committing to not donate to their former HEI until it has divested or organizing concurrent initiatives to support student calls for FFD [68,85].

The goals campaigns stated for FFD were generally broad, such as divestment from all types of fossil fuels, a wide contingent of the top fossil fuel companies (i.e., the CU 200), and of both direct and indirect investments. This consensus does not reflect how HEIs always act when pursuing divestment. Divestment strategies used by HEIs include divestment from all fossil fuel companies, divestment from the CU 200, and divestment from specific sectors, such as coal or tar sands; and HEIs may choose to divest from direct or both direct and indirect holdings [4,66,86]. Of US HEIs that have committed to FFD, 25% have committed to less than full forms of divestment as categorized by 350.org, including 16% of divesting HEIs that have committed solely to divestment from coal or coal and tar sands [33]. This suggests that campaigns generally advocate for the broadest form of FFD possible, while HEIs often choose more selective forms of FFD to actually pursue. In these cases, activists may continue to put pressure on HEIs for more extensive divestment [4,34,68].

Results show that calls for reinvestment are common among campaigns, but these were also found to be generally broad, rather than specific of where HEIs should reinvest. As was advocated for by some campaigns in the sample, reinvestment in clean energy has been among the calls made by activists since the beginning of the movement to redirect resources towards climate solutions [30]. However, a common narrative on what reinvestment should look like does not seem to have developed within the movement. Research has suggested that reinvestment has not had as much focus in the movement as divestment because it may be strategically disadvantageous to demand it as an additional step and because of beliefs among activists that it is technically more difficult and that there are not enough appropriate funds to reinvest into [30]. However, by not incorporating specific demands for reinvestment, campaigns risk HEIs reallocating money towards greenwashed alternatives, rather than solutions that build a more just society [37]. For example, research has indicated that FFD could move investment towards sectors of the economy that still have substantial exposure to greenhouse gas emissions, even when investing in “fossil free” funds [87,88].

The additional goals mentioned by nearly a quarter of campaigns, such as educating the public and advocating for climate action beyond the institution, demonstrate that groups working on FFD are not motivated solely by divestment and reinvestment and contribute in other valuable ways. This may reflect the multitude of ways in which students engage with sustainability movements on campus and within society [19].

Campaigns often used a combination of environmental, social, and economic themes in their messaging, reinforcing the notion of FFD fitting within the realm of sustainability, which can be described as the intersection of these areas [60,61]. Fossil fuels were presented as a key driver of environmental, social, and economic problems, namely climate change and its impacts on humans. FFD was seen as a tool to incite a transition away from fossil fuels and thus create a more sustainable society. Campaigns often saw it as the duty of their HEIs to help facilitate this transition because of their institutional values and important position within society. This aligns with the position of scholars who view FFD as a necessary direction for HE sustainability in the era of climate change that embraces more outward, transformative action, grounded in principles of equity and social justice [4,16,17,86,89].

True to the common narrative of HE FFD being a movement for justice, nearly half of campaigns incorporated language that framed their motivations around issues of justice, often in relation to the disproportionate impacts of climate change on certain groups of people. Some campaigns went beyond simply framing FFD as a justice issue and connected it to broader intersectional issues, such as racial or economic justice. However, there was still a lack of intersectionality in terms of connecting FFD to issues faced by specific marginalized groups, such as African Americans and Indigenous Peoples. Interestingly, while less than 1% of campaigns in this study directly addressed Indigenous issues, Maina et al. (2020) found that nearly 30% of Canadian HE FFD campaigns incorporate site-specific messaging addressing concerns of Indigenous groups, suggesting that Canadian campaigns have developed stronger connections with Indigenous groups than have campaigns in the US [29].

It is worth mentioning that, whereas the leadership of minority groups like African Americans, Indigenous Peoples, and Latinos have been important to the development of the environmental justice movement [39,40], research has noted the difficulty some US HE FFD campaigns have experienced in building diverse participant bases, perhaps due in part to HE FFD activists coming predominantly from backgrounds of relative privilege rather than from environmental justice communities [16,25,34]. This is reflected in the fact that no campaigns in this study mentioned specific local environmental justice issues. The focus of campaigns on the broad, global notion of “justice” rather than specifically who is effected by the injustice (e.g., local communities of color) that the findings point to may be a limitation for the movement in creating solidarity with impacted communities, building diverse bases of support, and developing a strong moral argument for divestment. However, this should not detract entirely from the strident focus on justice many campaigns in the movement have adopted that has been important in reframing climate change as a social justice issue in HE and broader public discourse [4,16,17].

Campaigns’ arguments mostly rested on the moral imperative of acting to mitigate societal crises, but a practical case was also often made on the grounds that FFD could benefit HEIs financially, such as by avoiding losses due to the riskiness of fossil fuel investments. The argument of fossil fuel companies being risky investments is often associated with the FFD movement, particularly the idea that fossil fuel stocks will become obsolete, or “stranded assets,” as increased regulations require fossil fuels to be kept in the ground to mitigate climate change [4,30,48,89]. Campaigns may showcase these arguments to appease concerns of administrators, who have been shown to commonly cite the financial benefits or risks to their HEIs in decisions committing to or rejecting FFD [4,17,49].

It should be emphasized that campaigns have not developed their goals and messaging in isolation but have likely been highly influenced by each other and the narratives presented by organizations supporting FFD. Maina et al., (2020) found “patterns of imitation” in the Canadian HE FFD movement in which campaigns borrowed messaging and tactics from each other in accordance with what was needed for the local context of their HEIs. They were also influenced by organizations such as 350.org, who provided online or in-person “sites of encounter” where ideas and resources were shared and disseminated among activists [29]. This phenomena of diffusion of ideas and practices among movement actors has been well documented within past social movements [90,91,92].

The commonalities seen in this study among campaign’s goals and the themes they used likely to some degree reflect a similar process of adopting objectives and messaging of other campaigns and organizations in the movement. For example, the request promoted by 350.org for HEIs to “immediately freeze any new investment in fossil fuel companies, and divest from direct ownership and any commingled funds that include fossil fuel public equities and corporate bonds within 5 years” became the baseline demand from campaigns early in the movement [25]. This was repeated almost word for word by a number of campaigns in this study and reflects the common goals of divestment from all types of fossil fuels, divestment of both direct and indirect fossil fuel investments, and completion of divestment within five years. Though campaigns arise and organize in a decentralized fashion, they still seem to form a unified movement with common goals and messaging through imitation and the influence of organizations.

5. Conclusions

This study provides an overview and analysis of the characteristics of US HE FFD campaigns, focused on the locations and types of institutions where campaigns occur, the stakeholders involved in campaigns and the goals they adopt, and the themes campaigns use in their messaging. Presented as ten years of campaigns organizing for FFD at HEIs approaches, this offers an important contribution, allowing an understanding of the nature of campaigns so far. However, there are still directions for future research that could be useful for better understanding the movement in the US.

There is a lack of clarity on how campaigns engage with and are influenced by the communities and regions in which they are located. Unlike actors in the grassroots environmental justice movement that the HE FFD movement takes inspiration from [40], the findings reveal that campaigns are not highly focused on pollution or inequities in their own areas. For example, no campaigns referenced local environmental justice issues and few demanded reinvestment into their local communities. However, this study was limited by only looking at short descriptions on campaigns’ Facebook pages, and there are certainly nuances to how campaigns interact with their local contexts that were not observed. Whether campaigns are inspired to organize by local environmental issues, how campaigns build solidarity with local disenfranchised communities, and whether campaigns or FFD commitments at HEIs have a reputational or financial impact on fossil fuel companies with operations in their respective regions would all be useful questions to explore. For example, these would help to better explain the spatial pattern of campaigns and whether campaigns could be more strategically located throughout the US.

Reinvestment is also an area that has received very little study. There are few sources of information that describe where HEIs have reinvested or committed to reinvest after FFD, beyond broad generalizations and a few mentions of specific cases. A comprehensive examination of where HEIs are reinvesting could be particularly insightful now, as some of the earlier divesting HEIs have had time to reallocate divested funds and research could help to understand where this money has gone. Though this study has suggested that campaigns do not tend to include specific targets for reinvestment in their demands, further exploration of how campaigns engage with the notion of reinvestment would be of interest to better understand the role it plays in campaigns and how activists are articulating a pathway for just reallocation of money currently invested in the fossil fuel industry.

Finally, most scholars have considered HE FFD from an isolated perspective in regard to other social movements. The results of this study pointed to some intersections between HE FFD and other social movements, such as with campaigns tying FFD to racial or economic justice issues. However, there is still a need to examine how HE FFD has been influenced by past social movements and interacts with current ones. Particularly, as movements addressing race and diversity like Black Lives Matter have found support from student activists in recent years [51], further study of the connections between these movements and HE FFD would be illuminating to the understanding of how it fits in with the broader sphere of progressive activism at HEIs.

It is clear from the analysis of campaigns’ goals and messaging that the HE FFD movement is pushing sustainability and climate action towards a greater embrace of systemic change and social justice. Nowhere is this more evident than within HE itself, where HEIs are being challenged to uphold their duty as influential societal actors by moving beyond incremental campus greening and engaging in a broader political arena of sustainability action with climate justice as the goal. HE professionals should take note of what campaigns are demanding and consider critically how the approach to sustainability at their own HEIs can better work to encourage the just economic transition needed to address climate change at the scale and speed necessary, through actions like FFD.

The results point to some ways in which the US HE FFD movement could be further developed to better confront the power of the fossil fuel industry and build capacity for a movement away from the extractive economy based in solidarity with impacted communities. For example, HE FFD organizers could work to build connections in areas that have not seen much activity, particularly in states with heavy fossil fuel production like Texas and North Dakota, to encourage and support the development of campaigns at HEIs there. As more HEIs commit to FFD and proceed with the divestment process, more focus may need to be devoted towards developing a consistent narrative within the movement around reinvestment to ensure that money is reallocated towards a more just economy, and not simply into greenwashed alternative investments. Finally, greater emphasis may need to be applied to solidarity with frontline and marginalized communities to develop the movement’s focus on justice. In particular, campaigns developing relationships with such communities within the localities of their HEIs may provide opportunities to draw needed attention to specific cases of injustice and even to support the prosperity and self-determination of these communities through community reinvestment initiatives.

Through wide-spread mobilization, a hardline stance against investments in the fossil fuel industry, and a propensity to focus on justice for the people most impacted by the climate crisis, HE FFD campaigns in the US have initiated a movement that has helped define an insurgent international wave of climate activism and has challenged embedded notions of sustainability. Led primarily by students, the movement is also empowering young people to engage in collective action for sustainability with aims that are radical and global in scope. At the beginning of a new decade, the movement continues to grow and hold significant power to undermine the dominance of the fossil fuel industry, shape narratives around climate change and sustainability, and ultimately drive a transition to a more just society. It is in the hands of future generations of activists, HEIs, and others involved in the movement to determine the impact HE FFD will have in the coming years.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/23/10069/s1, Table S1: Higher education institutions with fossil fuel divestment campaigns in study sample and URL of Facebook page used for each campaign.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.G. and L.A.D.; methodology, D.G. and L.A.D.; investigation, D.G.; writing—original draft preparation, D.G.; writing—review and editing, D.G. and L.A.D.; supervision, L.A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jon Bathgate for contributing to the GIS mapping.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. Global Warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, G.P.; Andrew, R.M.; Canadell, J.G.; Fuss, S.; Jackson, R.B.; Korsbakken, J.I.; Le Quéré, C.; Nakicenovic, N. Key Indicators to Track Current Progress and Future Ambition of the Paris Agreement. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2017, 7, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.B.; Friedlingstein, P.; Andrew, R.M.; Canadell, J.G.; Le Quéré, C.; Peters, G.P. Persistent Fossil Fuel Growth Threatens the Paris Agreement and Planetary Health. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, N.; Debski, J. Fossil Fuel Divestment: Implications for the Future of Sustainability Discourse and Action Within Higher Education. Local Environ. 2017, 22, 699–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAfee, K. Green Economy and Carbon Markets for Conservation and Development: A Critical View. Int. Environ. Agreem. 2016, 16, 333–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbloom, D.; Markard, J.; Geels, F.W.; Fuenfschilling, L. Opinion: Why Carbon Pricing is Not Sufficient to Mitigate Climate Change—And How “Sustainability Transition Policy” Can Help. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 8664–8668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, T. Conflicts Over Carbon Capture and Storage in International Climate Governance. Energy Policy 2017, 100, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spash, C.L. This Changes Nothing: The Paris Agreement to Ignore Reality. Globalizations 2016, 13, 928–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinar, A.; Skjærseth, J.B.; Jevnaker, T.; Wettestad, J. The Paris Agreement: Consequences for the EU and Carbon Markets? Politics Gov. 2016, 4, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelowa, A.; Shishlov, I.; Brescia, D. Evolution of International Carbon Markets: Lessons for the Paris Agreement. Wires Clim. Chang. 2019, 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, J.C.; Hernandez, M.E.; Román, M.; Graham, A.C.; Scholz, R.W. Higher Education as a Change Agent for Sustainability in Different Cultures and Contexts. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2008, 9, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molthan-Hill, P.; Worsfold, N.; Nagy, G.J.; Leal Filho, W.; Mifsud, M. Climate Change Education for Universities: A Conceptual Framework from an International Study. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 1092–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Morgan, E.A.; Godoy, E.S.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Bacelar-Nicolau, P.; Veiga Ávila, L.; Mac-Lean, C.; Hugé, J. Implementing Climate Change Research at Universities: Barriers, Potential, and Actions. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, G.; Dyer, M. Strategic Leadership for Sustainability by Higher Education: The American College & University Presidents’ Climate Commitment. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, L.P.; Martins, N.; Gouveia, J.B. Quest for a Sustainable University: A Review. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2015, 16, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, E.; Brunette, K.; Shelly, D.C.; Nicholson, S. Justice is the Goal: Divestment as Climate Change Resistance. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2016, 6, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grady-Benson, J.; Sarathy, B. Fossil Fuel Divestment in US Higher Education: Student-Led Organising for Climate Justice. Int. J. Justice Sustain. 2016, 21, 661–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenburg, D.; Fang, C.C. The Myth of Climate Neutrality: Carbon Onsetting as an Alternative to Carbon Offsetting. Sustain. J. Rec. 2015, 8, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J. Student-Led Action for Sustainability in Higher Education: A Literature Review. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2018, 19, 1095–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selby, D.; Kagawa, F. Runaway Climate Change as Challenge to the ‘Closing Circle’ of Education for Sustainable Development. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 4, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huckle, J.; Wals, A.E.J. The UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development: Business as Usual in the End. Environ. Educ. Res. 2015, 21, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, D.B. Neoliberal Ideology and Public Higher Education in the United States. J. Crit. Educ. Policy Stud. 2010, 8, 41–77. [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey, J. Regimes of Performance: Practices of the Normalised Self in the Neoliberal University. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2015, 36, 614–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, H.; Wright, T. Barriers to Sustainable Universities and Ways Forward: A Canadian Students’ Perspective. 3rd World Sustain. Forum 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grady-Benson, J. Fossil Fuel Divestment: The Power and Promise of a Student Movement for Climate Justice. Master’s Thesis, Pitzer College, Claremont, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cadan, Y.; Mokgopo, A.; Vondrich, C. $11 Trillion and Counting; 350.org: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey, E.; Mott, R.N. Philanthropy Rises to the Fossil Divest-Invest Challenge. Available online: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/philanthropy-rises-to-the_b_4690774 (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- McKibben, B. Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math. Available online: https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/global-warmings-terrifying-new-math-188550/ (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- Maina, N.M.; Murray, J.; McKenzie, M. Climate Change and the Fossil Fuel Divestment Movement in Canadian Higher Education: The Mobilities of Actions, Actors, and Tactics. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, N. Impacts of the Fossil Fuel Divestment Movement: Effects on Finance, Policy and Public Discourse. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemkus, S. Divest Ed Looks to Help Fill Gap in Fossil Fuel Divestment Movement. Available online: https://energynews.us/2019/02/19/northeast/divest-ed-looks-to-help-fill-gap-in-fossil-fuel-divestment-movement/ (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- Engelfried, N. How a New Generation of Climate Activists is Reviving Fossil Fuel Divestment and Gaining Victories. Available online: https://wagingnonviolence.org/2020/03/climate-activists-reviving-fossil-fuel-divestment/ (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- Divestment Commitments. Available online: https://gofossilfree.org/divestment/commitments/ (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Gibson, D. The U.S. Fossil Fuel Divestment Movement: Towards a Justice-Based Paradigm of Sustainability at Higher Education Institutions. Master’s Thesis, Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Carbondale, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Papscun, D. Divesting from a Distance. Available online: https://progressive.org/dispatches/divesting-from-a-distance-papscun-200615/ (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- Ansar, A.; Caldecott, B.; Tilbury, J. Stranded Assets and the Fossil Fuel Divestment Campaign: What Does Divestment Mean for the Valuation of Fossil Fuel Assets? Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ressler, L.; Schellentrager, M. A Complete Guide to Reinvestment. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/s3.350.org/images/Reivestment_Guide.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2020).

- Reinvestment. Available online: https://divested.betterfutureproject.org/reinvestment (accessed on 17 September 2020).

- Agyeman, J.; Schlosberg, D.; Craven, L.; Matthews, C. Trends and Directions in Environmental Justice: From Inequity to Everyday Life, Community, and Just Sustainabilities. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2016, 41, 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosberg, D.; Collins, L.B. From Environmental to Climate Justice: Climate Change and the Discourse of Environmental Justice. Wires Clim. Chang. 2014, 5, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, P.; Mulvaney, D. The Political Economy of the ‘Just Transition’. Geogr. J. 2013, 2, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, D.; Heffron, R. Just Transition: Integrating Climate, Energy, and Environmental Justice. Energy Policy 2018, 119, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, P.; Dorsey, M.K. Anatomies of Environmental Knowledge and Resistance: Diverse Climate Justice Movements and Waning Eco-Neoliberalism. J. Aust. Political Econ. 2010, 66, 286–316. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, N. This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ayling, J. A Contest for Legitimacy: The Divestment Movement and the Fossil Fuel Industry. Law Policy 2017, 39, 349–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKibben, B. At Last, Divestment is Hitting the Fossil Fuel Industry Where It Hurts. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/dec/16/divestment-fossil-fuel-industry-trillions-dollars-investments-carbon (accessed on 28 September 2020).

- Della Vigna, M.; Mehta, N.; Chreng, D. Re-Imagining Big Oils: How Energy Companies Can Successfully Adapt to Climate Change; Goldman Sachs: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schifeling, T.; Hoffman, A.J. Bill McKibben’s Influence on U.S. Climate Change Discourse: Shifting Field-Level Debates through Radical Flank Effects. Organ. Environ. 2017, 32, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, C.T. Rationale of Early Adopters of Fossil Fuel Divestment. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2016, 17, 506–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, J.C.; Frumhoff, P.C.; Yona, L. The Role of College and University Faculty in the Fossil Fuel Divestment Movement. Elem. Sci. Anthr. 2018, 6, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoads, R.A. Student Activism, Diversity, and the Struggle for a Just Society. J. Divers. High. Educ. 2016, 9, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammaerts, B. Social Media and Activism. In The International Encyclopedia of Digital Communication and Society; Mansell, R., Hwa, P., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 1027–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Allsop, B. Social Media and Activism: A Literature Review. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 18, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval-Almazan, R.; Gil-Garcia, J.R. Towards Cyberactivism 2.0? Understanding the Use of Social Media and Other Information Technologies for Political Activism and Social Movements. Gov. Inf. Q. 2014, 31, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gismondi, A.; Osteen, L. Student Activism in the Digital Age. New Dir. Stud. Lead. 2017, 2017, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, N.L.; Matais, C.E.; Montoya, R. Activism or Slacktivism? The Potentials and Pitfalls of Social Media in Contemporary Student Activism. J. Divers. High. Educ. 2017, 10, 400–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau of the Census. Chapter 6: Statistical Groupings of States and Counties. Geographic Areas Reference Manual; Bureau of the Census: Suitland, MD, USA, 1994.

- US Department of Energy. The National Energy Modeling System: An Overview 2018; US Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2019.

- Das, S.; Gupta, R.; Kabundi, A. The Blessing of Dimensionality in Forecasting Real House Price Growth in the Nine Census Divisions of the U.S. J. Hous. Res. 2010, 19, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three Pillars of Sustainability: In Search of Conceptual Origins. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoolman, E.D.; Guest, J.S.; Bush, K.F.; Bell, A.R. How Interdisciplinary is Sustainability Research? Analyzing the Structure of an Emerging Scientific Field. Sustain. Sci. 2012, 7, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansmann, R.; Mieg, H.A.; Frischknecht, P. Principal Sustainability Components: Empirical Analysis of Synergies Between the Three Pillars of Sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2012, 19, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E.; LeQuesne, T. The University of California Has Finally Divested From Fossil Fuels. Available online: https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/california-fossil-fuels/ (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- Connolly, L.; Di Rosa, L.; Elivo, R.; Francis, T.; Griep, C.; Ito, C.; Palmieri, M. The Carbon Underground 2017; Fossil Free Indexes: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Divestment Commitments: Classifications. Available online: https://gofossilfree.org/divestment-commitments-classifications/ (accessed on 19 June 2020).

- Ryan, C.; Marsicano, C. Examining the Impact of Divestment from Fossil Fuels on University Endowments. N. Y. Univ. J. Law Bus. 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, J.K.; Dempsey, J.; Gibbs, P. The Power of Fossil Fuel Divestment (And its Secret). In A World to Win: Contemporary Social Movements and Counter-Hegemony; Carroll, W.K., Sarker, K., Eds.; ARP Books: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2016; pp. 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, V. The Ivy League Has Over $135 Billion in Endowment. Not a Single University Has Pledged to Fully Divest from Fossil Fuels. Available online: https://www.columbiaspectator.com/news/2020/02/17/the-ivy-league-has-over-135-billion-inendowment-not-a-single-university-has-pledged-to-fully-divest-from-fossil-fuels/ (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Holden, E. Harvard and Yale Students Disrupt Football Game for Fossil Fuel Protest. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/nov/23/harvard-yale-football-game-protest-fossil-fuels (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Number of Degree-Granting Postsecondary Institutions and Enrollment in These Institutions, by Enrollment Size, Control, and Classification of Institution: Fall 2018. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_317.40.asp (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Watanabe, T. UC Becomes Nation’s Largest University to Divest Fully from Fossil Fuels. Available online: https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-05-19/uc-fossil-fuel-divest-climate-change (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Degree-Granting Postsecondary Institutions, by Control and Classification of Institution and State or Jurisdiction: 2018-19. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_317.20.asp (accessed on 21 October 2020).

- US Census Bureau. 2010 Census of Population and Housing, Population and Housing Unit Counts; US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- Wilson, S.G.; Fischetti, T.R. Coastline Population Trends in the United States: 1960 to 2008; US Census Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 2010.

- Jones, J.M. Conservatives Greatly Outnumber Liberals in 19 U.S. States. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/poll/247016/conservatives-greatly-%20outnumber-liberals-states.aspx (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Howe, P.D.; Mildenberger, M.; Marlon, J.R.; Leiserowitz, A. Geographic Variation in Opinions on Climate Change at State and Local Scales in the USA. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Where Our Oil Comes From. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/oil-and-petroleum-products/where-our-oil-comes-from.php (accessed on 18 July 2020).

- Where Our Natural Gas Comes From. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/natural-gas/where-our-natural-gas-comes-from.php (accessed on 18 July 2020).

- Where Our Coal Comes from. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/coal/where-our-coal-comes-from.php (accessed on 18 July 2020).

- North Dakota—State Energy Profile Analysis. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/state/analysis.php?sid=ND (accessed on 18 July 2020).

- Bohannon, R.; Blinnikov, M. Habitat Fragmentation and Breeding Bird Populations in Western North Dakota after the Introduction of Hydraulic Fracturing. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2019, 109, 1471–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiang, S.; Kopp, R.; Jina, A.; Rising, J.; Delgado, M.; Mohan, S.; Rasmussen, D.J.; Muir-Wood, R.; Wilson, P.; Oppenheimer, M.; et al. Estimating Economic Damage from Climate Change in the United States. Science 2017, 356, 1362–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinich, J.; Neumann, J.; Ludwig, L.; Jantarasami, L. Risks of Sea Level Rise to Disadvantaged Communities in the United States. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2013, 18, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauer, M.E.; Evans, J.M.; Mishra, D.R. Millions Projected to Be at Risk from Sea-Level Rise in the Continental United States. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2016, 6, 691–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedler, D. Harvard Alumni Are Turning Up the Heat on Fossil Fuel Divestment. Available online: https://www.motherjones.com/environment/2020/01/harvard-alumni-are-turning-up-the-heat-on-fossil-fuel-divestment/ (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Leal Filho, W.; Beynaghi, A.; Al-Amin, A.Q.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Esteban, M.; Mozafari, M. Low-Carbon Transition Through a Duty to Divest: Back to the Future, Ahead to the Past. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 94, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.; Dowlatabadi, H. Understanding the Shadow Impacts of Investment and Divestment Decisions: Adapting Economic Input-Output Models to Calculate Biophysical Factors of Financial Returns. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 106, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.; Dowlatabadi, H. Divest from the Carbon Bubble? Reviewing the Implications and Limitations of Fossil Fuel Divestment for Institutional Investors. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2015, 5, 59–80. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland, C.J.; Reibstein, R. The Path to Fossil Fuel Divestment for Universities: Climate Responsible Investment. SSRN Electron. J. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.J.; Soule, S.A. Social Movement Organizational Collaboration: Networks of Learning and the Diffusion of Protest Tactics, 1960–1995. Am. J. Sociol. 2012, 117, 1674–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soule, S.A. The Student Divestment Movement in the United States and Tactical Diffusion: The Shantytown Protest. Soc. Forces 1997, 75, 855–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soule, S.A. Diffusion Processes Within and Across Movements. In The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements; Snow, D.A., Soule, S.A., Kriesi, H., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 294–310. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).