The Crisis of Public Health and Infodemic: Analyzing Belief Structure of Fake News about COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Literature on Fake News and Rumors

2.2. Risk Communication Versus Risk Perpception

2.3. Risk Communication Factor

2.4. Risk Perception Factor

3. Method

4. Measurement

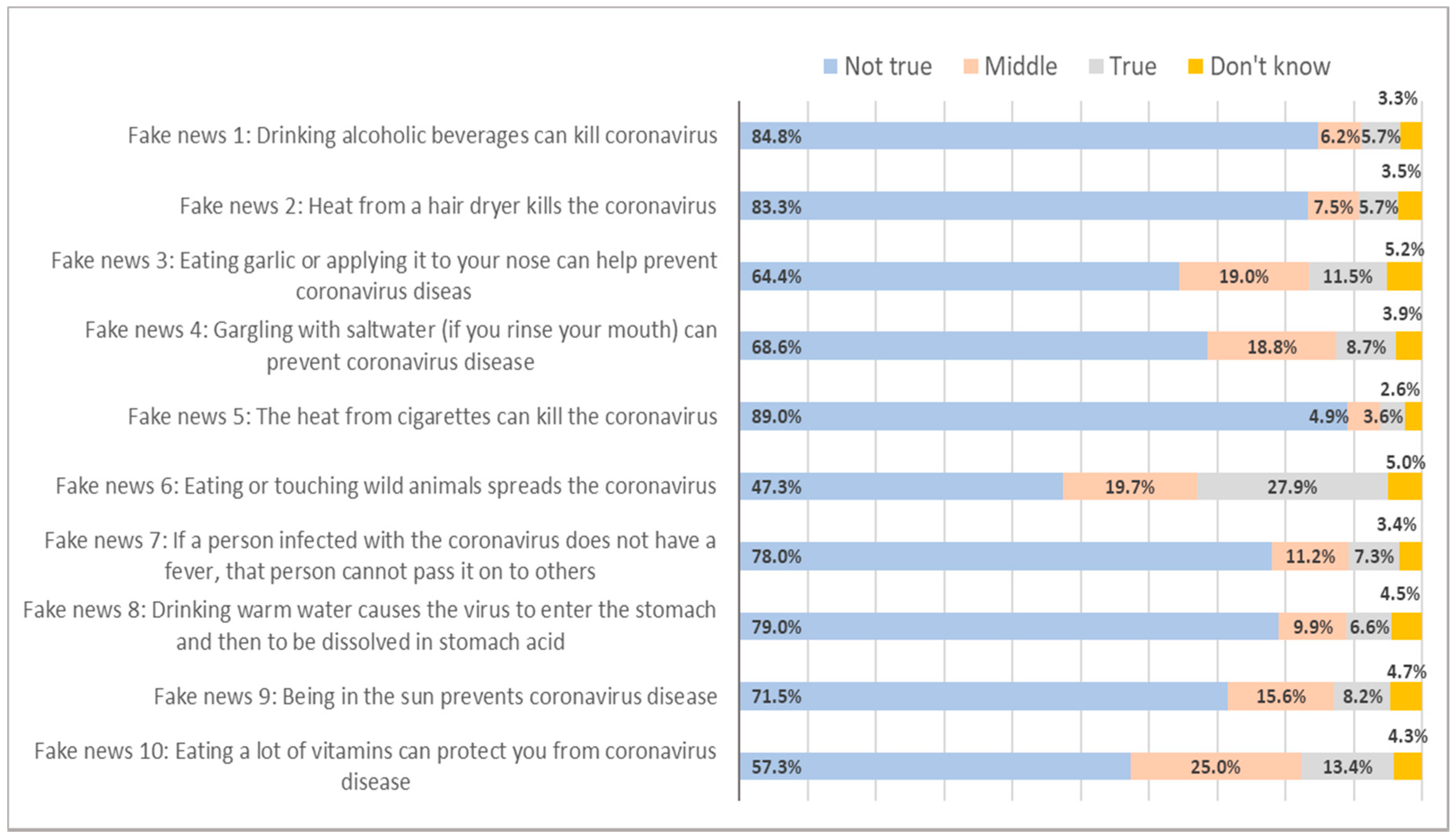

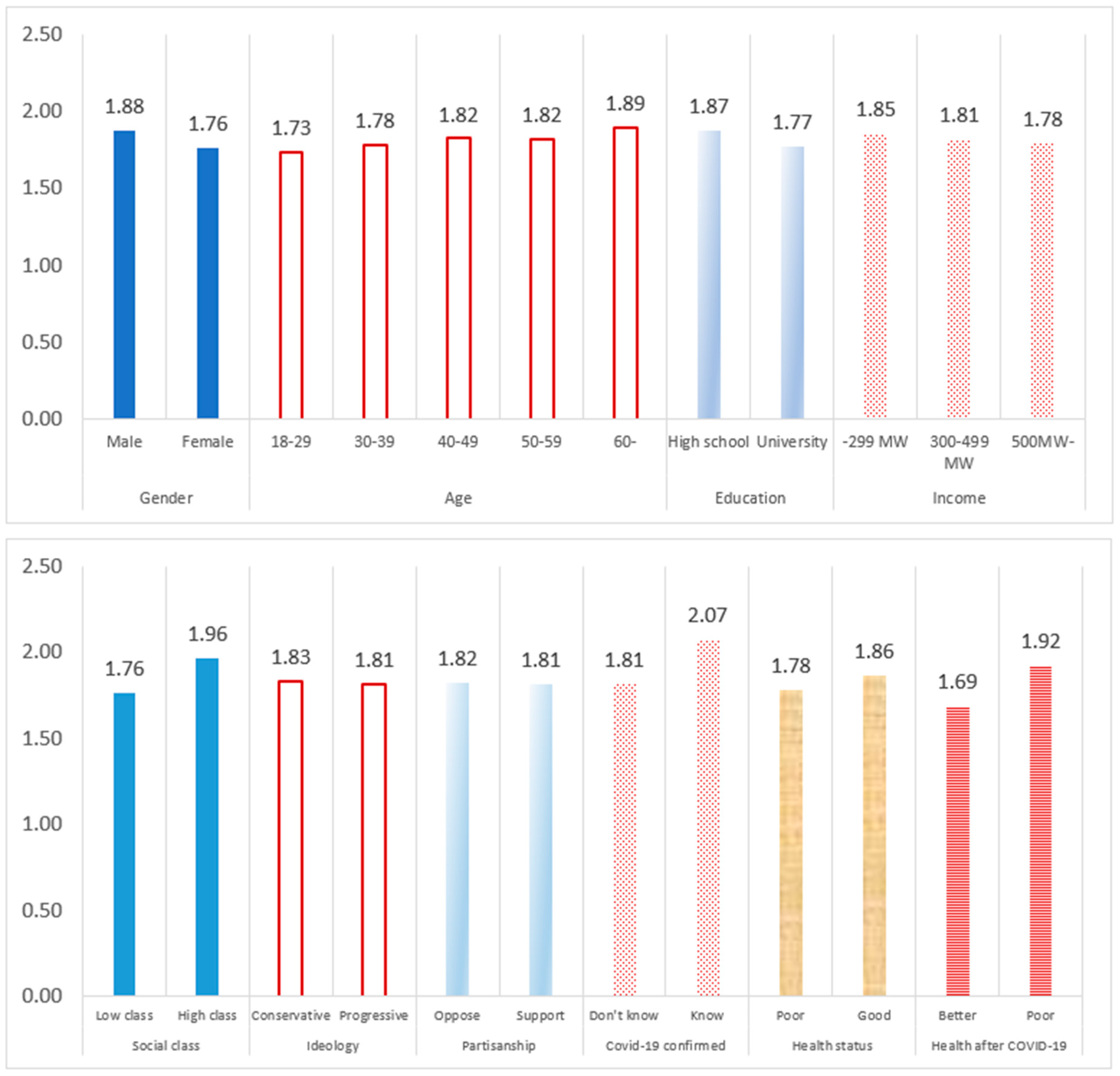

5. Analysis

6. Discussion

7. Implications and Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kawasaki, A.; Meguro, K.; Hener, M. Comparing the disaster information gathering behavior and post-disaster actions of Japanese and foreigners in the Kanto area after the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake. In Proceedings of the 2012 WCEE, Lisbon, Portugal, 24–28 September 2012; Available online: http://www.iitk.ac.in/nicee/wcee/article/WCEE2012_2649.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2012).

- PAHO (Pan American Health Organization). Understanding the Infodemic and Misinformation in the Fight Against COVID-19. Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/documents/understanding-infodemic-and-misinformation-fight-against-covid-19 (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- MOHW (Ministry of Health and Welfare). COVID-19. Fact & Issue Check. Available online: http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/factBoardList.do (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Kim, S.; Kim, S. Impact of the Fukushima nuclear accident on belief in rumors: The role of risk perception and communication. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernandes, C.M.; Montuori, C. The misinformation network and health at risk: An analysis of fake news included in ‘The 10 reasons why you shouldn’t vaccinate your child’. RECIIS 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, B.; Mawson, A.R.; Payton, M.; Guignard, J.C. Disaster mythology and fact: Hurricane Katrina and social attachment. Public Health Rep. 2008, 123, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vosoughi, S.; Roy, D.; Aral, S. The spread of true and false news online. Science 2018, 359, 1146–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscadelli, A.; Albora, G.; Biamonte, M.A.; Giorgetti, D.; Innocenzio, M.; Paoli, S.; Lorini, C.; Bonanni, P.; Bonaccorsi, G. Fake news and Covid-19 in Italy: Results of a quantitative observational study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, D.; Valenzuela, S.; Katz, J.; Miranda, J.P. From belief in conspiracy theories to trust in others: Which factors influence exposure, believing and sharing fake news. Gabriele Meiselwitz, 2019. In Social Computing and Social Media. Design, Human Behavior and Analytics. HCII 2019, Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Meiselwitz, G., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 11578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazer, D.; Baum, M.A.; Benkler, Y.; Berinsky, A.J.; Greenhill, K.M.; Menczer, F.; Metzger, M.J.; Nyhan, B.; Pennycook, G.; Rothschild, D.; et al. The science of fake news. Science 2018, 359, 1094–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, D.G.; Rand, D.G. Lazy, not biased: Susceptibility to partisan fake news is better explained by lack of reasoning than by motivated reasoning. Cognition 2019, 188, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, A. Psychology of rumor. Public Opin. Q. 1944, 8, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosnow, R.L. Psychology of rumor reconsidered. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 87, 578–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fonzo, N.; Bordia, P. Rumor Psychology: Social and Organizational Approaches; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Allport, G.W.; Postman, L.J. The psychology of rumor: Holt, Rinehart & Winston: New York. J. Clin. Psychol. 1947, 3, 402. [Google Scholar]

- House of Commons. Disinformation and “Fake News”: Interim Report: Government Response to the Committee’s Fifth Report of Session 2017–2019. House of Commons. 2018. Available online: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmcumeds/1630/1630.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Jung, D.; Kim, S. Response to risky society and searching for new governance: An analysis of the effects of value, perception, communication, and resource factors on the belief in rumors about particulate matter. Korean J. Public Adm. 2020, 58, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Difonzo, N.; Bordia, P. Rumor, gossip and urban legends. Diogenes 2007, 54, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandoc, E.C.; Lim, Z.W.; Ling, R. Defining “Fake News”. Digit. J. 2017, 6, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, R. Where did that rumor come from. Fortune Mag. Arch. 1979, 100, 130–137. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel, A.J. Rumors and Rumor Control: A Manager’s Guide to Understanding and Combating Rumors; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fearn-Banks, K. Crisis Communications: A Casebook Approach; Routledge: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. The Future of Truth and Misinformation Online. 2017. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2017/10/19/the-future-of-truth-and-misinformation-online/ (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Lefevere, J.; De Swert, K.; Walgrave, S. Effects of popular exemplars in television news. Commun. Res. 2012, 39, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, C.J.; Guo, L.; Amazeen, M.A. The agenda-setting power of fake news: A big data analysis of the online media landscape from 2014 to 2016. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 2028–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grinberg, N.; Joseph, K.; Friedland, L.; Swire-Thompson, B.; Lazer, D. Fake news on twitter during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Science 2019, 363, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guess, A.M.; Nagler, J.; Tucker, J.A. Less than you think: Prevalence and predictors of fake news dissemination on Facebook. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Institute for Basic Science (IBS). 2020. Available online: https://www.ibs.re.kr/cop/bbs/BBSMSTR_000000000971/selectBoardArticle.do?nttId=18985 (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Allport, G.W.; Postman, L.J. An analysis of rumor. Public Opin. Q. 1947, 10, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosnow, R.L. Inside Rumor: A personal journey. Am. Psychol. 1991, 46, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, D.; Leiss, W. Mad Cows and Mother’s Milk: Case Studies in Risk Communication; McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal, QC, Canada, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C.E.; Weaver, W. The Mathematical Theory of Communication; University of Illinois Press: Urbana, IL, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Kasperson, R.E.; Renn, O.; Slovic, P.; Brown, H.S.; Emel, J.; Goble, R.; Kasperson, J.X.; Ratick, S. The social amplification of risk: A conceptual framework. Risk Anal. 1988, 8, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sjöberg, L. The methodology of risk perception research. Qual. Quant. 2000, 34, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. The Perception of Risk; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fischhoff, B.; Slovic, P.; Lichtenstein, S.; Read, S.; Combs, B. How safe is safe enough? A psychometric study of attitudes towards technological risks and benefits. Policy Sci. 1978, 9, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, E.G. Birth control discontinuance as a diffusion process. Stud. Fam. Plan. 1984, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Chou, W.-S.; Hsu, Y.-L. The factors of influencing college student’s belief in consumption-type internet rumors. Int. J. Cyber Soc. Educ. 2009, 2, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, T.; Benson, V. Spreading disinformation on facebook: Do trust in message source, risk propensity, or personality affect the organic reach of “fake news”? Soc. Media Soc. 2019, 5, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lampinen, J.M.; Smith, V.L. The incredible (and sometimes incredulous) child witness: Child eyewitnesses’ sensitivity to source credibility cues. J. Appl. Psychol. 1995, 80, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visentin, M.; Pizzi, G.; Pichierri, M. Fake news, real problems for brands: The impact of content truthfulness and source credibility on consumers’ behavioral intentions toward the advertised brands. J. Interact. Mark. 2019, 45, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Dennis, A.R. Says Who? The Effects of Presentation Format and Source Rating on Fake News in Social Media. MIS Q. 2019, 43, 1025–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Van Der Meer, T.G.L.A.; Lee, Y.-I.; Lu, X. The effects of corrective communication and employee backup on the effectiveness of fighting crisis misinformation. Public Relat. Rev. 2020, 46, 101910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moravec, P.; Minas, R.; Dennis, A.R. Fake news on social media: People believe what they want to believe when it makes no sense at all. MIS Q. 2019, 43, 1343–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bago, B.; Rand, D.G.; Pennycook, G. Fake news, fast and slow: Deliberation reduces belief in false (but not true) news headlines. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2020, 149, 1608–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trumbo, C.W. Heuristic-systematic information processing and risk judgment. Risk Anal. 1999, 19, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; You, M. Psychological and behavioral responses in South Korea during the early stages of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.F.; Cheng, Y. Consumer response to fake news about brands on social media: The effects of self-efficacy, media trust, and persuasion knowledge on brand trust. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2019, 29, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A. Motivation with misinformation: Conceptualizing lacuna individuals and publics as knowledge-deficient, issue-negative activists. J. Public Relat. Res. 2017, 29, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paor, S.; Heravi, B.R. Information literacy and fake news: How the field of librarianship can help combat the epidemic of fake news. J. Acad. Libr. 2020, 46, 102218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, A.; Wirth, W.; Müller, P. We are the people and you are fake news: A social identity approach to populist citizens’ false consensus and hostile media perceptions. Commun. Res. 2020, 47, 201–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lewandowsky, S.; Ecker, U.K.; Cook, J. Beyond misinformation: Understanding and coping with the “Post-Truth” Era. J. Appl. Res. Mem. Cogn. 2017, 6, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Balmas, M. When fake news becomes real: Combined exposure to multiple news sources and political attitudes of inefficacy, alienation, and cynicism. Commun. Res. 2014, 41, 430–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.Y.; Lee, B.J.; Cha, S.M. Impact of online restaurant information WOM characteristics on the effect of WOM-Focusing on the mediating role of source-credibility. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2011, 24, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yun, H.-J.; Ahn, S.-H.; Lee, C.-C. Determinants of trust in power blogs and their effect on purchase intention. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2012, 12, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Talwar, S.; Dhir, A.; Kaur, P.; Zafar, N.; Arlasheedi, M.A. Why do people share fake news? Associations between the dark side of social media use and fake news sharing behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.P.K.; Srivastava, A.; Geethakumari, G. A psychometric analysis of information propagation in online social networks using latent trait theory. Computing 2016, 98, 583–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benková, Z. The spread of disinformation. why do people believe them and how to combat them.The importance of media literacy. Mark. Identity 2018, 6 Pt 2, 16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, A.; Guillory, J.; Hancock, J. Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 8788–8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slovic, P.; Layman, M.; Kraus, N.; Flynn, J.; Chalmers, J.; Gesell, G. Perceived risk, stigma, and potential economic impacts of a high-level nuclear waste repository in Nevada. Risk Anal. 1991, 11, 683–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakir, V.; McStay, A. Fake news and the economy of emotions. Digit. Journal. 2018, 6, 154–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bavel, J.J.; Baicker, K.; Boggio, P.S.; Capraro, V.; Cichocka, A.; Cikara, M.; Crockett, M.J.; Crum, A.J.; Douglas, K.M.; Druckman, J.N.; et al. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschen, J. Investigating the emotional appeal of fake news using artificial intelligence and human contributions. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2020, 29, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sangalang, A.; Ophir, Y.; Cappella, J.N. The potential for narrative correctives to combat misinformation. J. Commun. 2019, 69, 298–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berduygina, O.N.; Vladimirova, T.N.; Chernyaeva, E.V. Trends in the spread of fake news in the mass media. Media Watch. 2019, 10, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbaudo, P. Fake news and all-too-real emotions: Surveying the social media battlefield. Brown J. World Aff. 2018, 25, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Borges-Tiago, M.T.; Tiago, F.; Silva, O.; Martínez, J.M.G.; Botella-Carrubi, D. Online users’ attitudes toward fake news: Implications for brand management. Psychol. Mark. 2020, 37, 1171–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbu, N.; Oprea, D.-A.; Negrea-Busuioc, E.; Radu, L. ‘They can’t fool me, but they can fool the others’! Third person effect and fake news detection. Eur. J. Commun. 2020, 35, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axt, J.R.; Landau, M.J.; Kay, A.C. The psychological appeal of fake-news attributions. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 848–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.M.; McKeever, B.W.; McKeever, R.; Kim, J.K. From social media to mainstream news: The information flow of the vaccine-autism controversy in the US, Canada, and the UK. Health Commun. 2019, 34, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krouwel, A.; Kutiyski, Y.; Van Prooijen, J.-W.; Martinsson, J.; Markstedt, E. Does extreme political ideology predict conspiracy beliefs, economic evaluations and political trust? Evidence from Sweden. J. Buddh. Ethics 2018, 5, 435–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hajli, N.; Lin, X. Exploring the security of information sharing on social networking sites: The role of perceived control of information. J. Bus. Ethic 2016, 133, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. 1st WHO Infodemiology Conference. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2020/06/30/default-calendar/1st-who-infodemiology-conference (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Rubin, V.L. Disinformation and misinformation triangle: A conceptual model for “fake news” epidemic, causal factors and interventions. J. Doc. 2019, 75, 1013–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roozenbeek, J.; Van Der Linden, S. The fake news game: Actively inoculating against the risk of misinformation. J. Risk Res. 2019, 22, 570–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-S.; Chen, K.-N. Post-event information presented in a question form eliminates the misinformation effect. Br. J. Psychol. 2013, 104, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H. A War of (Mis) Information: The political effects of rumors and rumor rebuttals in an authoritarian country. Br. J. Politi. Sci. 2017, 47, 283–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vafeiadis, M.; Bortree, D.S.; Buckley, C.; Diddi, P.; Xiao, A. Refuting fake news on social media: Nonprofits, crisis response strategies and issue involvement. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2020, 29, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahng, M.R.; Lee, H.; Rochadiat, A. Public relations practitioners’ management of fake news: Exploring key elements and acts of information authentication. Public Relat. Rev. 2020, 46, 101907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, M.; Quattrociocchi, W.; Galeazzi, A.; Valensise, C.M.; Brugnoli, E.; Schmidt, A.L.; Zola, P.; Zollo, F.; Scala, A. The COVID-19 social media infodemic. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goniewicz, K.; Khorram-Manesh, A.; Hertelendy, A.J.; Goniewicz, M.; Naylor, K.; Burkle, F.M., Jr. Current response and management decisions of the European Union to the COVID-19 outbreak: A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciampaglia, G.L. Fighting fake news: A role for computational social science in the fight against digital misinformation. J. Comput. Soc. Sci. 2018, 1, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkle, F.M.; Bradt, D.A.; Green, J.; Ryan, B.J. Global public health database support to population-based management of pandemics and global public health crises, Part II: The database. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2020, 2020, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Gupta, A.; Kauten, C.; Deokar, A.V.; Qin, X. Detecting fake news for reducing misinformation risks using analytics approaches. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 279, 1036–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC (European Commission). Coronavirus: EU Strengthens Action to Tackle Disinformation. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_1006.2020 (accessed on 11 November 2020).

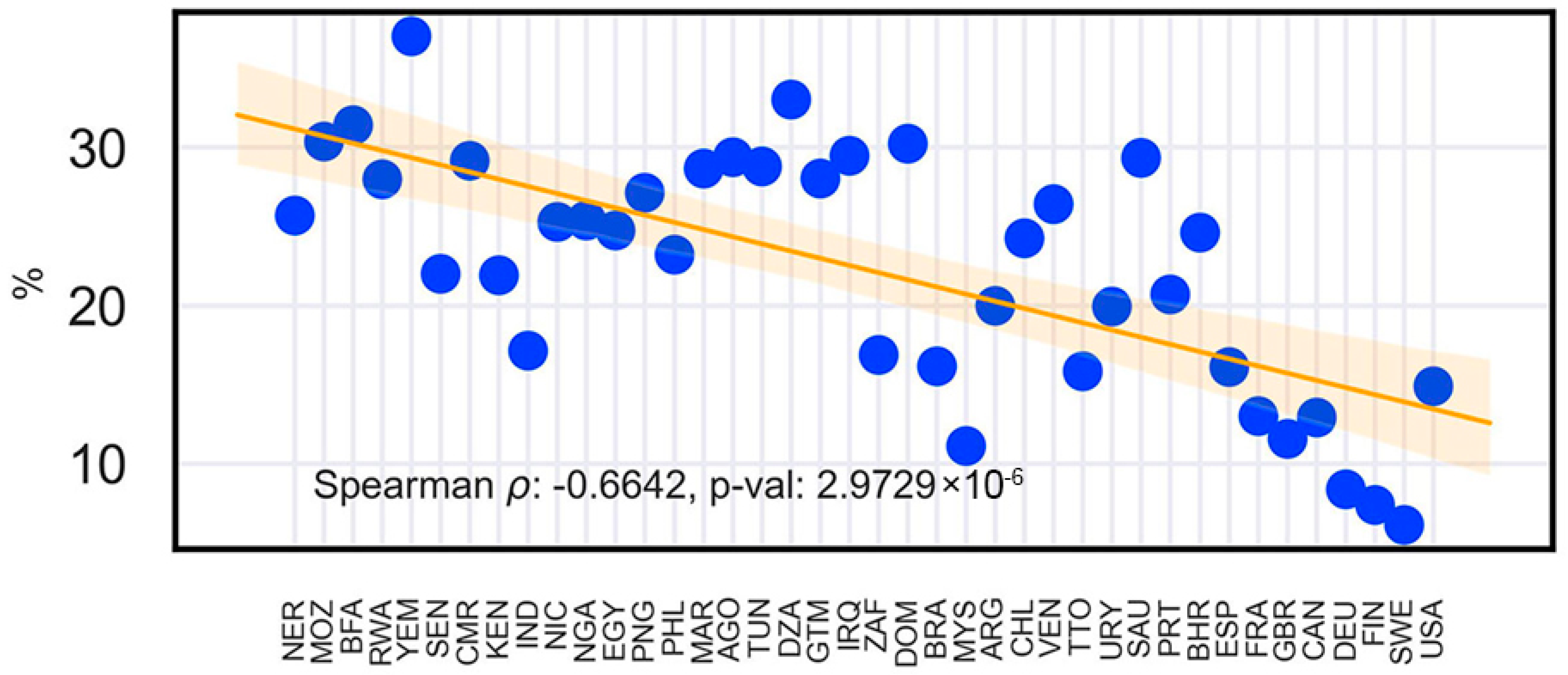

- Khorram-Manesh, A.; Carlström, E.; Hertelendy, A.J.; Goniewicz, K.; Casady, C.B.; Burkle, F. Does the prosperity of a country play a role in COVID-19 outcomes? Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolverton, C.; Stevens, D. The impact of personality in recognizing disinformation. Online Inf. Rev. 2019, 44, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Irresolvable cultural conflicts and conservation/development arguments: Analysis of Korea’s Saemangeum project. Policy Sci. 2003, 36, 125–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, H. Does cultural capital matter? Cultural divide and quality of life. Soc. Indic. Res. 2009, 93, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, S. Exploring the Effect of Four Factors on Affirmative Action Programs for Women. Asian J. Women’s Stud. 2014, 20, 31–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, S. Analysis of the impact of health beliefs and resource factors on preventive behaviors against the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, S. Does trust matter? analyzing the impact of trust on the perceived risk and acceptance of nuclear power energy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, J.; Kim, S. Analysis of the impact of values and perception on climate change skepticism and its implication for public policy. Climate 2018, 6, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kwon, S.A.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.E. Analyzing the determinants of individual action on climate change by specifying the roles of six values in South Korea. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.; Lee, J.E.; Kim, D. Searching for the next new energy in energy transition: Comparing the impacts of economic incentives on local acceptance of fossil fuels, renewable, and nuclear energies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.; Kwon, S.A.; Lee, J.E.; Ahn, B.-C.; Lee, J.H.; Chen, A.; Kitagawa, K.; Kim, D.; Wang, J. analyzing the role of resource factors in citizens’ intention to pay for and participate in disaster management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.; Kim, D. Does government make people happy? Exploring new research directions for government’s roles in happiness. J. Happiness Stud. 2011, 13, 875–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Choi, S.-O.; Wang, J. Individual perception vs. structural context: Searching for multilevel determinants of social acceptance of new science and technology across 34 countries. Sci. Public Policy 2014, 41, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, Y.; Kim, S. Testing the heuristic/systematic information-processing model (HSM) on the perception of risk after the Fukushima nuclear accidents. J. Risk Res. 2014, 18, 840–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Kim, S. Comparative Analysis of Public Attitudes toward Nuclear Power Energy across 27 European Countries by Applying the Multilevel Model. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.; Kim, S. Exploring the determinants of perceived risk of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, J.; Kim, S. Searching for new directions for energy policy: Testing the cross-effect of risk perception and cyberspace factors on online/offline opposition to nuclear energy in South Korea. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Humprecht, E. Where ‘fake news’ flourishes: A comparison across four Western democracies. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2019, 22, 1973–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J.; Kim, S.; Kim, S. Searching for new directions for energy policy: Testing three causal models of risk perception, attitude, and behavior in nuclear energy context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratianu, C. (Ed.) Organizational Knowledge Dynamics: Managing Knowledge Creation, Acquisition, Sharing, and Transformation: Managing Knowledge Creation, Acquisition, Sharing, and Transformation; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Vargo, C. “fake news” and emerging online media ecosystem: An integrated intermedia agenda-setting analysis of the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Commun. Res. 2020, 47, 178–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrick, J.G.; Erlichman, S. How audience involvement and social norms foster vulnerability to celebrity-based dietary misinformation. Psychol. Popul. Media Cult. 2020, 9, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Risk Communication Model | Risk Perception Paradigm | |

|---|---|---|

| Discipline | - Information theory, communications | - Psychology |

| Key variables | - Receiver, message (information), source | - Perceived benefit, perceived risk, stigma, trust, knowledge |

| Assumed mode of judgment | - Interdependent judgment | - Independent judgment |

| Methods | - Qualitative and quantitative methods | - Quantitative methods, mainly surveys |

| Strengths | - Highlights the roles and functions of risk communication factors - Explains dynamics | - Causal explanations - Explanatory power for risk judgment |

| Weaknesses | - Limited generalizability - Oversimplifies complex communication processes | - Dismisses the context - Inability to explain perception changes |

| Variable | Item | Reliability |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived risk | I am relatively more likely to get coronavirus disease than others are. | 0.846 |

| I am more vulnerable to coronavirus disease compared to others. | ||

| Perceived benefit | If the coronavirus problem is solved, it will be a great benefit to our society. | 0.812 |

| When the coronavirus disease is overcome, our society will develop greatly. | ||

| Knowledge | I know a lot about coronavirus disease. | 0.840 |

| I know more about coronavirus disease than others do. | ||

| Stigma | People with coronavirus disease are bad people. | 0.919 |

| People with coronavirus disease are dirty. | ||

| Source credibility | How much do you trust the following subjects for providing coronavirus-related information? (Response scale: 1 = extremely distrust, 2 = slightly distrust, 3 = usually, 4 = slightly trust, 5 = extremely trust). ① Central Disease Control Headquarters, ② Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC), and ③ Jeong Eun-kyeong, Director of KCDC, Korea | 0.809 |

| Quantity of information | I have more coronavirus-related information than others have. | 0.887 |

| I have obtained a lot of meaningful information related to coronavirus disease. | ||

| Quality of information | Coronavirus-related information provided by the government is objective based on facts. | 0.912 |

| Coronavirus-related information provided by the government is scientifically based and professional. | ||

| Heuristic processing | Rather than analyzing coronavirus-related information carefully and logically, I make judgments based on intuitive feelings. | 0.816 |

| I interpret coronavirus-related information emotionally rather than rationally. | ||

| Receiver’s ability | I can understand coronavirus-related issues. | 0.664 |

| I have the ability to distinguish between truth and fiction in coronavirus-related information. |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Belief in fake news | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Gender (female) | −0.072 *** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Age | 0.066 ** | −0.003 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 4. Education | −0.065 ** | −0.074 *** | −0.305 *** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 5. Income | −0.028 | −0.017 | −0.072 *** | 0.207 *** | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 6. Social class | 0.129 *** | 0.006 | −0.022 | 0.210 *** | 0.343 *** | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 7. Ideology (progressive) | −0.012 | 0.059 ** | −0.125 *** | 0.084 *** | 0.007 | 0.059 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 8. Partisanship | −0.006 | 0.000 | −0.103 *** | 0.068 *** | 0.023 | 0.052 ** | 0.564 *** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 9. Knowing the confirmed case | 0.059 ** | −0.015 | −0.040 | 0.036 | 0.029 | 0.020 | 0.024 | 0.023 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 10. Health status | 0.091 *** | −0.022 | −0.033 | 0.121 *** | 0.165 *** | 0.271 *** | 0.075 *** | 0.083 *** | 0.004 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 11. Health status after COVIID-19 | 0.154 *** | 0.054 ** | 0.019 | −0.049 * | −0.038 | −0.039 | 0.032 | −0.106 *** | 0.000 | −0.146 *** | 1 | |||||||||

| 12. Perceived risk | 0.158 *** | −0.011 | 0.104 *** | −0.064 ** | −0.079 *** | −0.060 * | 0.020 | −0.031 | 0.035 | −0.264 *** | 0.341 *** | 1 | ||||||||

| 13. Perceived benefit | −0.156 *** | 0.004 | −0.014 | 0.121 *** | 0.077 *** | 0.044 * | 0.179 *** | 0.287 *** | −0.002 | 0.211 *** | −0.102 *** | −0.058 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 14. Trust | −0.074 *** | −0.049 * | 0.076 *** | 0.042 | 0.050 ** | 0.156 *** | 0.055 ** | 0.114 *** | 0.038 | 0.122 *** | −0.094 *** | −0.078 *** | 0.098 *** | 1 | ||||||

| 15 Knowledge | 0.071 *** | −0.066 ** | 0.041 | 0.115 *** | 0.088 *** | 0.159 *** | 0.136 *** | 0.123 *** | 0.052 ** | 0.202 *** | 0.077 *** | 0.075 *** | 0.198 *** | 0.105 *** | 1 | |||||

| 16. Stigma | 0.387 *** | −0.073 *** | −0.068 *** | −0.034 | 0.011 | 0.136 *** | 0.018 | −0.027 | −0.005 | 0.024 | 0.224 *** | 0.186 *** | −0.197 *** | −0.119 *** | 0.112 *** | 1 | ||||

| 17. Source credibility | −0.114 *** | 0.012 | 0.090 *** | 0.007 | 0.037 | 0.008 | 0.206 *** | 0.302 *** | 0.021 | 0.109 *** | −0.087 *** | −0.003 | 0.286 *** | 0.098 *** | 0.095 *** | −0.166 *** | 1 | |||

| 18. Quality of information | −0.080 *** | 0.008 | 0.023 | 0.030 | 0.030 | 0.017 | 0.356 *** | 0.582 *** | −0.001 | 0.162 *** | −0.183 *** | −0.060 * | 0.376 *** | 0.140 *** | 0.194 *** | −0.147 *** | 0.493 *** | 1 | ||

| 19. Quantity of information | 0.116 *** | −0.045 * | 0.065 ** | 0.057 * | 0.064 ** | 0.093 *** | 0.165 *** | 0.247 *** | 0.019 | 0.188 *** | 0.082 *** | 0.100 *** | 0.199 *** | 0.081 *** | 0.454 *** | 0.051 ** | 0.214 *** | 0.406 *** | 1 | |

| 20. Heuristic processing | 0.215 *** | −0.023 | 0.025 | −0.071 *** | −0.025 | 0.024 | 0.077 *** | 0.093 *** | 0.011 | 0.037 | 0.143 *** | 0.217 *** | 0.011 | −0.023 | 0.045 | 0.158 *** | 0.036 | 0.136 *** | 0.318 *** | 1 |

| 21. Receiver’s ability | −0.006 | −0.059 ** | 0.008 | 0.110 *** | 0.080 *** | 0.130 *** | 0.125 *** | 0.187 *** | 0.014 | 0.196 *** | −0.012 | 0.017 | 0.237 *** | 0.084 *** | 0.446 *** | −0.069 *** | 0.203 *** | 0.303 *** | 0.451 *** | 0.042 * |

| B | S.E. | Beta | T-Value | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controlled Variables | Constant | 0.592 | 0.227 | 2.607 | 0.009 | |

| Gender (female) | −0.071 ** | 0.036 | −0.046 | −1.988 | 0.047 | |

| Age | 0.004 *** | 0.001 | 0.072 | 2.892 | 0.004 | |

| Education level | −0.056 | 0.039 | −0.036 | −1.431 | 0.153 | |

| Income | −0.093 ** | 0.042 | −0.055 | −2.224 | 0.026 | |

| Social class | 0.042 *** | 0.012 | 0.089 | 3.415 | 0.001 | |

| Ideology | −0.013 | 0.012 | −0.030 | −1.069 | 0.285 | |

| Partisanship | 0.018 ** | 0.008 | 0.072 | 2.243 | 0.025 | |

| COVID-19 confirmed case | 0.271 *** | 0.103 | 0.060 | 2.634 | 0.009 | |

| Health status | 0.118 *** | 0.025 | 0.123 | 4.735 | 0.000 | |

| Health state after COVID-19 | 0.041 * | 0.023 | 0.045 | 1.756 | 0.079 | |

| Risk Perception Factors (F1) | Perceived risk | 0.063 ** | 0.023 | 0.071 | 2.730 | 0.006 |

| Perceived benefit | −0.093 *** | 0.024 | −0.099 | −3.804 | 0.000 | |

| Trust | −0.054 ** | 0.024 | −0.054 | −2.287 | 0.022 | |

| Knowledge | −0.012 | 0.033 | −0.010 | −0.357 | 0.721 | |

| Stigma | 0.276 *** | 0.024 | 0.289 | 11.350 | 0.000 | |

| Communication Factors(F2) | Source credibility | −0.050 * | 0.025 | −0.054 | −2.011 | 0.044 |

| Quality of information | −0.037 | 0.029 | −0.043 | −1.264 | 0.206 | |

| Quantity of information | 0.071 *** | 0.030 | 0.071 | 2.365 | 0.018 | |

| Heuristic processing | 0.115 *** | 0.024 | 0.117 | 4.694 | 0.000 | |

| Receiver’s ability | −0.010 | 0.034 | −0.008 | −0.307 | 0.759 | |

| F-Value/R2/Ad. R2 | 33.123 ***/0.230/0.219 | |||||

| Controlled variables | F-Value/R2/Ad. R2 | 7.979 ***/0.041/0.036 | ||||

| F1 | F-Value/R2/Ad. R2 | 59.706 ***/0.166/0.163 | ||||

| F2 | F-Value/R2/Ad. R2 | 25.502 ***/0.077/0.073 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, S.; Kim, S. The Crisis of Public Health and Infodemic: Analyzing Belief Structure of Fake News about COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9904. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239904

Kim S, Kim S. The Crisis of Public Health and Infodemic: Analyzing Belief Structure of Fake News about COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability. 2020; 12(23):9904. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239904

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Seoyong, and Sunhee Kim. 2020. "The Crisis of Public Health and Infodemic: Analyzing Belief Structure of Fake News about COVID-19 Pandemic" Sustainability 12, no. 23: 9904. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239904

APA StyleKim, S., & Kim, S. (2020). The Crisis of Public Health and Infodemic: Analyzing Belief Structure of Fake News about COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability, 12(23), 9904. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239904