Determining Food Security in Crisis Conditions: A Comparative Analysis of the Western Balkans and the EU

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

- —represents the positive flow;

- —represents the negative flow;

- n—represents numbers of alternatives;

- A—represents a set of potential alternatives A;

- a—represents observed alternative;

- b—represents other alternatives that belong to A;

- —represents a multicriteria preference degree.

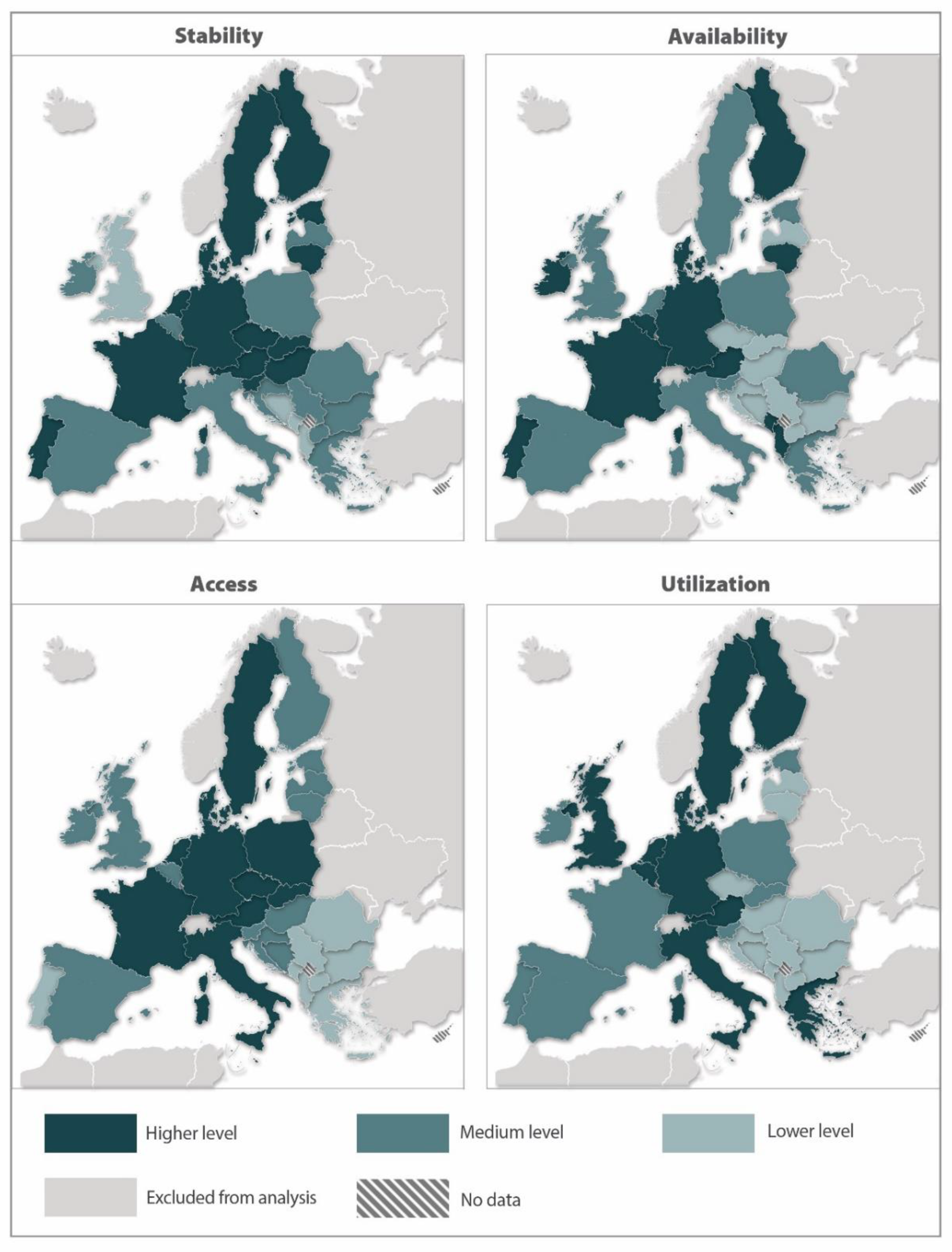

- STABILITY

- Cereal import dependency ratio (percent)

- Per capita food supply variability (kcal/cap/day)

- Percent of arable land equipped for irrigation (percent)

- Political stability and absence of violence/terrorism (index)

- Value of food imports in total merchandise exports (percent)

- AVAILABILITY

- Average dietary energy supply adequacy (percent)

- Average protein supply (g/cap/day)

- Average supply of protein of animal origin (g/cap/day)

- ACCESS

- Gross domestic product per capita, PPP, dissemination (constant 2011 international dollars)

- Prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity in the total population (percent)

- Prevalence of severe food insecurity in the total population (percent)

- UTILISATION

- Percentage of population using safely managed drinking water services (percent)

- Percentage of population using safely managed sanitation services (percent)

- Prevalence of anemia among women of reproductive age (15–49 years)

- Prevalence of obesity in the adult population (18 years and older)

- —represents the level of food security in the country i;

- —represents the share of the added value of agriculture in GDP in the country i;

- —represents the value of agricultural production per capita in the country i;

- —represents the share of export of agricultural products in total export in the country i;

- —represents land productivity in the country i;

- —random error of the model.

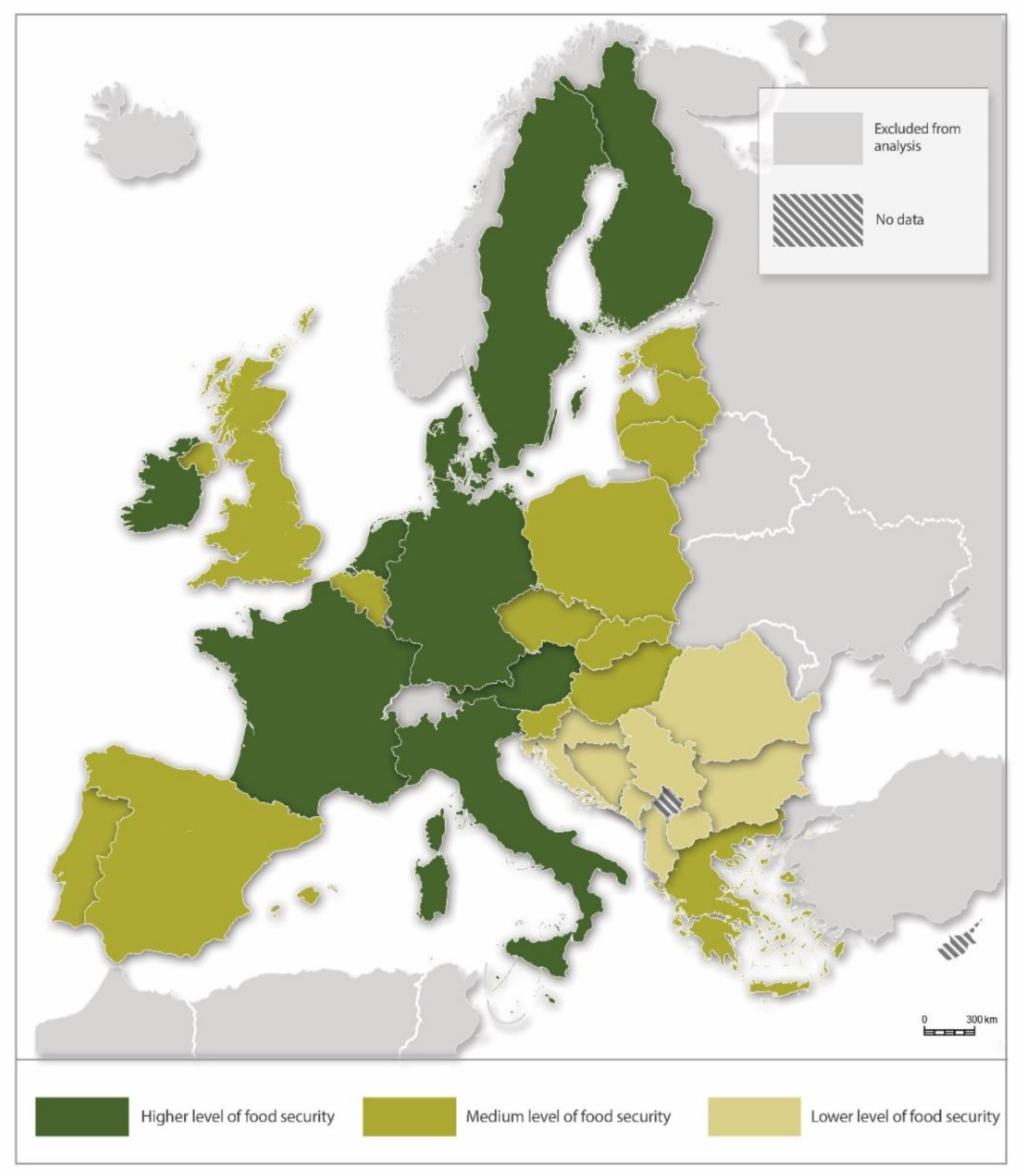

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- All analyzed countries are nutritionally secure, although some Western Balkan countries are highly dependent on imports of agri-food products, but the modern retail sector allows imports from relatively developed countries of the region and the EU. Such a foreign trade balance is not a threat to food security, it is a troubling indicator of the underdeveloped sector as well problems in the supply chain itself. In that context, in crisis cases where foreign trade flows are disturbed, food security in Western Balkan countries could be more endangered, primarily because of its export dependency (except in Serbia) and underdeveloped supply chain.

- Comparative analysis of food security indicates an obvious gap between the countries of the Western Balkans and the EU, but there is also a distinction between the EU countries themselves;

- Economic development, among other factors, has a significant impact on the level of food security of the country, which puts the countries of the Western Balkans in a worse position than the EU countries;

- Differences in agricultural structure, state support to agriculture, and level of integration of supply chains create gap between food security of Western Balkan and EU. Due to this, research results of this paper could be very useful for policymakers because this research has defined the factors influencing food security in Western Balkan and EU countries the most.

- The extensive structure of agricultural production, as well as the presence of small family farms, and the present rural poverty, is a significant constraint in the further development of agricultural production in the Western Balkans;

- The countries of the Western Balkans, except Croatia, are not part of the EU food system, i.e., they do not have an adequate level of support for the agricultural sector in relation to the EU member states;

- The lower level of development characterizes supply chains in the Western Balkans, so the main challenges in improving supply chains are reflected in lowering transaction costs and improving product quality through innovation and investing in new technologies.

- The lower level of food security in the Western Balkans countries compared to the EU can become a problem in crisis conditions, such as political instability, the migrant crisis, and the state of the pandemic. This is particularly pronounced in countries with high food supply variability, dependence on cereal imports, and lower GDP per capita.

- Based on the current COVID-19 pandemic crisis, there are a few possible scenarios considering food security. Namely, this crisis as an effect has a potential rise in food prices and income decline, disruption of food supply chains, global recession, and export restrictions. Thus, this research is essential for policymakers to identify factors that should be taken into account to maintain and improve food security.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Indicators | Average | Standard Deviation | Coefficient of Variation in % | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cereal import dependency ratio (percent) | −23.53 | 87.95 | −3.74 | −229.40 | 93.50 |

| Per capita food supply variability (kcal/cap/day) | 43.94 | 30.30 | 0.69 | 14.00 | 155.00 |

| Percent of arable land equipped for irrigation (percent) | 18.09 | 22.06 | 1.22 | 0.10 | 71.20 |

| Political stability and absence of violence/terrorism (index) | 0.55 | 0.41 | 0.74 | −0.38 | 1.20 |

| Value of food imports in total merchandise exports (percent) | 12.00 | 18.68 | 1.56 | 4.00 | 109.00 |

| Average dietary energy supply adequacy (percent) | 131.77 | 10.09 | 0.08 | 108.00 | 150.00 |

| Average protein supply (g/cap/day) | 101.34 | 12.84 | 0.13 | 64.70 | 125.00 |

| Average supply of protein of animal origin (g/cap/day) | 57.30 | 11.77 | 0.21 | 32.30 | 74.30 |

| Gross domestic product per capita, PPP, dissemination (constant 2011 international $) | 37187.19 | 15078.81 | 0.41 | 13287.00 | 80353.00 |

| Prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity in the total population (percent) | 9.51 | 6.31 | 0.66 | 3.63 | 38.23 |

| Prevalence of severe food insecurity in the total population (percent) | 1.92 | 1.87 | 0.97 | 0.50 | 10.50 |

| Percentage of population using safely managed drinking water services (percent) | 94.21 | 7.65 | 0.08 | 70.00 | 100.00 |

| Percentage of population using safely managed sanitation services (percent) | 80.89 | 24.30 | 0.30 | 16.60 | 99.20 |

| Prevalence of anaemia among women of reproductive age (15–49 years) | 21.02 | 5.60 | 0.27 | 6.10 | 29.40 |

| Prevalence of obesity in the adult population (18 years and older) | 22.78 | 2.59 | 0.11 | 17.90 | 28.90 |

| Indicators | Average | Standard Deviation | Coefficient of Variation in % | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value added in agriculture (% of GDP) | 3.41 | 3.70 | 1.08 | 0.60 | 19.85 |

| Agricultural production in USD per capita | 473.43 | 209.34 | 0.44 | 153.06 | 1045.81 |

| Share of export of agricultural products in total export | 10.71 | 5.17 | 0.48 | 3.19 | 21.41 |

| Land productivity in USD per hectare | 1547.58 | 1666.33 | 1.08 | 376.50 | 7779.76 |

References

- World Bank. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/5970 (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Pinstrup-Andersen, P. Food security: Definition and measurement. Food Secur. 2009, 1, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-y4671e.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- FAO. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3434e.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Jambor, A.; Babu, S. Competitiveness of Global Agriculture; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/y5898e07.htm (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. Available online: http://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/ca9692en/ (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Bruinsma, J. The Resource Outlook to 2050: By how much do land, water and crop yields need to increase by 2050? How to Feed the World in 2050. In Proceedings of a Technical Meeting of Experts, Rome, Italy, 24–26 June 2009; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Giménez, E.; Shattuck, A.; Altieri, M.; Herren, H.; Gliessman, S. We already grow enough food for 10 billion people… and still can’t end hunger. J. Sustain. Agric. 2012, 36, 595–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosekov, A.Y.; Ivanova, S.A. Food security: The challenge of the present. Geoforum 2018, 91, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.D.; Mishra, R.; Maurya, K.K.; Singh, R.B.; Wilson, D.W. Estimates for world population and global food availability for global health. In The Role of Functional Food Security in Global Health; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, M.A.; Gregory, P.J. Soil, food security and human health: A review. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2015, 66, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strange, R.N.; Scott, P.R. Plant disease: A threat to global food security. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol 2005, 43, 83–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, E.B.; Cockx, L.; Swinnen, J. Culture and food security. Glob. Food Secur. 2018, 17, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavas, J.P. On food security and the economic valuation of food. Food Policy 2017, 69, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Brzeska, J. Sustainable food security and nutrition: Demystifying conventional beliefs. Glob. Food Secur. 2016, 11, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matkovski, B.; Zekić, S.; Savić, M.; Radovanov, B. Trade of agri-food products in the EU enlargement process: Evidence from the Southeastern Europe. Agric. Econ. Czech 2018, 64, 357–366. [Google Scholar]

- Matkovski, B.; Radovanov, B.; Zekić, S. The Effects of Foreign Agri-food Trade Liberalization in South East Europe. Ekon. Cas. 2018, 66, 945–966. [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowski, M.; Myachenkova, Y. The Western Balkans on the road to the European Union. Bruegel Policy Contrib. 2018, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Mizik, T.; Meyers, W. The possible effects of the EU accession on the Western Balkans agricultural trade. Econ. Agric. 2013, 60, 857–865. [Google Scholar]

- Latham, J.R. There’s enough food for everyone, but the poor can’t afford to buy it. Nature 2000, 404, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brankov, T.; Lovre, I. Food security in the Former Yugoslav Republics. Econ. Agric. 2017, 64, 701–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papić Brankov, T.; Milovanović, M. Measuring food security in the Republic of Serbia. Econ. Agric. 2015, 62, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovljenić, M.; Raletić-Jotanović, S. Food security issues in the former Yugoslav countries. Outlook Agric. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Food Security Index (GFSI). Available online: https://foodsecurityindex.eiu.com/ (accessed on 21 October 2020).

- Brans, J.; Mareschal, B.; Vincke, P. PROMETHEE: A New Family of Outranking Methods in Multicriteria Analysis; Universite Libre de Bruxelles: Bruxelles, Belgium, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Available online: http://faostat.fao.org/ (accessed on 7 October 2020).

- World Bank. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 9 October 2020).

- Gajić, M.; Matkovski, B.; Zekić, S.; Đokić, D. Development performances of agriculture in the Danube region countries. Econ. Agric. 2015, 62, 921–936. [Google Scholar]

- Volk, T.; Rednak, M.; Erjavec, E.; Rac, I.; Zhllima, E.; Gjeci, G.; Bajramović, S.; Vaško, Ž.; Kerolli-Mustafa, M.; Gjokaj, E.; et al. Agricultural Policy Developments and EU Approximation process in the Western Balkan Countries; Ilic, B., Pavloska-Gjorgjieska, D., Ciaian, P., Eds.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Volk, T.; Rednak, M.; Erjavec, E. Cross Country Analysis of agriculture and Agricultural Policy of Southeastern European Countries in Comparison with the European Union. In Agricultural Policy and European Integration in Southeastern Europe; Volk, T., Erjavec, E., Mortensen, K., Eds.; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Budapest, Hungary, 2014; pp. 9–38. [Google Scholar]

- Swinnen, J.; McDermott, J. COVID-19: Assessing Impacts and Policy Responses for Food and Nutrition Security; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Worldometers. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/? (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Jámbor, A.; Czine, P.; Balogh, P. The Impact of the Coronavirus on Agriculture: First Evidence Based on Global Newspapers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsellino, V.; Kaliji, S.A.; Schimmenti, E. COVID-19 Drives Consumer Behaviour and Agro-Food Markets towards Healthier and More Sustainable Patterns. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapp, J.; Moseley, W.G. This food crisis is different: COVID-19 and the fragility of the neoliberal food security order. J. Peasant Stud. 2020, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erjavec, E.; Mortensen, K.; Volk, T.; Rednak, M.; Eberlin, R.; Ludvig, K. Gap analysis and recommendations. In Agricultural Policy and European Integration in Southeastern Europe; Erjavec, E., Volk, T., Mortense, K.N., Eds.; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Budapest, Hungary, 2014; pp. 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Končar, J.; Grubor, A.; Marić, R.; Vučenović, S.; Vukmirović, G. Setbacks to IoT implementation in the function of FMCG supply chain sustainability during COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, L.A.; Fleischhacker, S.; Anderson-Steeves, B.; Harper, K.; Winkler, M.; Racine, E.; Baquero, B.; Gittelsohn, J. Healthy Food Retail during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Challenges and Future Directions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Končar, J.; Grubor, A.; Marić, R. Improving the placement of food products of organic origin on the AP Vojvodina market. Strateg. Manag. 2019, 24, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, S.Z.; Dracea, R.; Vlădulescu, C. Comparative Study of Certification Schemes for Food Safety Management Systems in the European Union Context. Amfiteatru Econ. 2018, 20, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glauber, J.; Laborde, D.; Martin, W.; Vos, R. COVID-19: Trade restrictions are worst possible response to safeguard food security. In COVID-19 & Global Food Security; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, S.; Wunsch, N. Money, power, glory: The linkages between EU conditionality and state capture in the Western Balkans. J. Eur. Public Policy 2020, 27, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, N.; Rodić, V.; Vittuari, M. Structural change and transition in the agricultural sector: Experience of Serbia. Communist Post-Communist Stud. 2017, 50, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovre, K. Technical change in agricultural development of the Western Balkan countries. In 152nd EAAE Seminar-Emerging Technologies and the Development of Agriculture (1-14); Tomić, D., Lovre, K., Subić, J., Ševarlić, M., Eds.; Serbian Association of Agricultural Economists, Faculty of Economics in Subotica, Institute of Agricultural Economics: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Erjavec, E.; Volk, T.; Rednak, M.; Ciaian, P.; Lazdinis, M. Agricultural policies and European Union accession processes in the Western Balkans: Aspirations versus reality. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2020, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Description | Source | Expected Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Value added in agriculture (% of GDP) | World Bank | negative | |

| Agricultural production in USD per capita | FAOs | positive | |

| Share of export of agricultural products in total export | FAO | negative | |

| Land productivity in USD per hectare | FAO | positive |

| Rank | Country | Food Security | Stability | Availability | Access | Utilization | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Austria | 0.4978 | 0.4067 | 0.5111 | 0.6222 | 0.5083 | Higher level of food security |

| 2. | Germany | 0.4222 | 0.2333 | 0.2222 | 0.8222 | 0.5083 | |

| 3. | Denmark | 0.4111 | 0.3067 | 0.4444 | 0.5222 | 0.4333 | |

| 4. | Finland | 0.3911 | 0.3000 | 0.6000 | 0.0333 | 0.6167 | |

| 5. | Netherlands | 0.3756 | 0.2333 | 0.0222 | 0.4778 | 0.7417 | |

| 6. | Sweden | 0.3489 | 0.4600 | 0.1111 | 0.4556 | 0.3083 | |

| 7. | France | 0.2933 | 0.1467 | 0.7111 | 0.3778 | 0.1000 | |

| 8. | Malta | 0.2578 | 0.1333 | 0.4667 | 0.4222 | 0.1333 | |

| 9. | Italy | 0.1800 | 0.0333 | 0.1889 | 0.2222 | 0.3250 | |

| 10. | Ireland | 0.1467 | −0.0333 | 0.6444 | 0.2000 | −0.0417 | |

| 11. | Spain | 0.1044 | 0.0067 | 0.1333 | 0.1000 | 0.2083 | Medium level of food security |

| 12. | Estonia | 0.1022 | 0.1533 | −0.0556 | 0.1778 | 0.1000 | |

| 13. | Portugal | 0.0867 | 0.0600 | 0.7222 | −0.4667 | 0.0583 | |

| 14. | Poland | 0.0600 | 0.0000 | −0.0111 | 0.4000 | −0.0667 | |

| 15. | Belgium | 0.0578 | −0.2333 | 0.2000 | −0.2000 | 0.5083 | |

| 16. | Czechia | 0.0444 | 0.2200 | −0.5556 | 0.6889 | −0.2083 | |

| 17. | Slovenia | 0.0356 | 0.2467 | −0.3667 | 0.1778 | −0.0333 | |

| 18. | Lithuania | 0.0289 | 0.0867 | 0.7889 | −0.2444 | −0.4083 | |

| 19. | United Kingdom | 0.0267 | −0.4400 | 0.0222 | 0.2000 | 0.4833 | |

| 20. | Slovakia | −0.0400 | 0.2000 | −0.9556 | 0.3778 | 0.0333 | |

| 21. | Greece | −0.1333 | −0.2000 | −0.0778 | −0.6444 | 0.2917 | |

| 22. | Hungary | −0.1667 | 0.2000 | −0.6222 | 0.0222 | −0.4250 | |

| 23. | Latvia | −0.1756 | −0.1333 | −0.4111 | 0.0444 | −0.2167 | |

| 24. | Romania | −0.2800 | −0.0267 | 0.1889 | −0.7778 | −0.5750 | Lower level of food security |

| 25. | Montenegro | −0.3378 | −0.6267 | 0.4556 | −0.6111 | −0.3667 | |

| 26. | Croatia | −0.3667 | −0.1867 | −0.6444 | 0.0000 | −0.6583 | |

| 27. | Albania | −0.3756 | −0.4000 | 0.3778 | −1.000 | −0.4417 | |

| 28. | Bulgaria | −0.4489 | −0.1200 | −0.8000 | −0.6111 | −0.4750 | |

| 29. | Serbia | −0.4622 | −0.0467 | −0.8667 | −0.6000 | −0.5750 | |

| 30. | North Macedonia | −0.5200 | −0.1800 | −0.9111 | −0.8000 | −0.4417 | |

| 31. | Bosnia and Herzegovina | −0.5644 | −0.8000 | −0.5333 | −0.3889 | −0.4250 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Ratio | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| const | 0.1154900 | 0.1050900 | 1.0990 | 0.2819 |

| −0.0395801 | 0.0096626 | −4.0962 | 0.0004 | |

| 0.0005480 | 0.0001878 | 2.9173 | 0.0072 | |

| −2.7961000 | 0.7581260 | −3.6882 | 0.0010 | |

| 0.0000384 | 0.0000213 | 1.7968 | 0.0840 | |

| Mean dependent var | 0.000000 | S.D. dependent var | 0.305939 | |

| Sum squared resid | 0.901949 | S.E. of regression | 0.186253 | |

| R-squared | 0.678788 | Adjusted R-squared | 0.629371 | |

| F (4, 26) | 13.73587 | p-value (F) | 0.000003 | |

| Log-likelihood | 10.83927 | Akaike criterion | −11.67854 | |

| Schwarz criterion | −4.508606 | Hannan-Quinn | −9.341321 |

| Scenario | Cause | Potential Consequences | Policy Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food price increase and income decline | COVID-19 | Food supply chains disruption High food prices The massive job losses Income decline Questionable quality of nutrition | Strengthening self-sufficiency in food production by a consistent agricultural policy Create an agricultural policy that support the improvement of agricultural productivity Strengthening regional cooperation Accelerate the EU accession process |

| Export restrictions | COVID-19 | Food shortages in some Western Balkan countries High food prices in some Western Balkan countries Questionable quality of nutrition | |

| Trade distractions in Western Balkans | Unstable political situation in the Western Balkans | Food shortages in some Western Balkan countries | |

| The migrant crisis and political situation in the region | Migrant crisis | Additional political destabilization of the region that may have consequences for trade and food availability |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matkovski, B.; Đokić, D.; Zekić, S.; Jurjević, Ž. Determining Food Security in Crisis Conditions: A Comparative Analysis of the Western Balkans and the EU. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9924. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239924

Matkovski B, Đokić D, Zekić S, Jurjević Ž. Determining Food Security in Crisis Conditions: A Comparative Analysis of the Western Balkans and the EU. Sustainability. 2020; 12(23):9924. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239924

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatkovski, Bojan, Danilo Đokić, Stanislav Zekić, and Žana Jurjević. 2020. "Determining Food Security in Crisis Conditions: A Comparative Analysis of the Western Balkans and the EU" Sustainability 12, no. 23: 9924. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239924

APA StyleMatkovski, B., Đokić, D., Zekić, S., & Jurjević, Ž. (2020). Determining Food Security in Crisis Conditions: A Comparative Analysis of the Western Balkans and the EU. Sustainability, 12(23), 9924. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239924