Subcentres as Destinations: Job Decentralization, Polycentricity, and the Sustainability of Commuting Patterns in Canadian Metropolitan Areas, 1996–2016

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

Analytical Framework

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Subcentres Identification

3.3. Types of Subcentres and Their Attributes

3.4. Commuting Pattern: Travel Modes and Distances

4. Results

4.1. Polycentricity of Metropolitan Areas

4.2. Evolution of Employment by Subcentres

4.3. Commuting Trends in CMAs Employment Zones

4.4. Evolution of Travel Distances

4.4.1. Toward the CBDs and Subcentres

4.4.2. Distance Travelled by Types of Subcentres

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sims, R.; Schaeffer, R.; Creutzig, F.; Cruz-Núñez, X.; D’Agosto, M.; Dimitriu, D.; Figueroa Meza, M.J.; Fulton, L.; Kobayashi, S.; Lah, O.; et al. Transport. In Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovern-mental Panel on Climate Change; Edenhofer, O., Pichs-Madruga, R., Sokona, Y., Farahani, E., Kadner, S., Seyboth, K., Adler, A., Baum, I., Brunner, S., Eickemeier, P., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- García-Palomares, J.C. Urban sprawl and travel to work: The case of the metropolitan area of Madrid. J. Transp. Geogr. 2010, 18, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaugh, K.; Miranda-Moreno, L.; El-Geneidy, A. The effect of neighbourhood characteristics, accessibility, home-work location, and demographics on commuting distances. Transportation 2010, 37, 627–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulibdeh, A.; Zaidan, E.; Abuelgasim, A. Urban Form and Travel Behavior as Tools to Assess Sustainable Transportation in the Greater Toronto Area. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2015, 141, 05014020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamruzzaman, M.; Shatu, F.M.; Hine, J.; Turrell, G. Commuting mode choice in transit oriented development: Disentangling the effects of competitive neighbourhoods, travel attitudes, and self-selection. Transp. Policy 2015, 42, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, L.; Schneider, R. Different ways to get to the same workplace: How does workplace location relate to commuting by different income groups? Transp. Policy 2017, 59, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, S.; Cao, X.; Mokhtarian, P. Correlation or causality between the built environment and travel behavior? Evidence from Northern California. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2005, 10, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Handy, S.; Cao, X.; Mokhtarian, P. Self-Selection in the Relationship between the Built Environment and Walking: Empirical Evidence from Northern California. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2006, 72, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanen, T.; Mokhtarian, P. What affects commute mode choice: Neighborhood physical structure or preferences toward neighborhoods ? J. Transp. Geogr. 2005, 13, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cao, X.; Mokhtarian, P.; Handy, S. Examining the Impacts of Residential Self-Selection on Travel Behaviour: A Focus on Empirical Findings. Transp. Rev. 2009, 29, 359–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sénécal, G.; Haf, R.; Hamel, P.J.; Poitras, C.; Vachon, N. La forme de l’agglomération montréalaise et la réduction du gaz à effet de serre: La polycentricité est-elle durable? Rev. Can. Sci. Régionales 2002, 25, 135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Shearmur, R. Travel from Home: An Economic Geography of Commuting Distances in Montreal. Urban Geogr. 2006, 27, 330–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbonne, R.; Shearmur, R.; Coffey, W. Les nouvelles dynamiques intra-métropolitaines de l’emploi favorisent-elles des migrations pendulaires plus «durables» ? le cas de la région métropolitaine de Montréal, 1998–2003. Géographie Économie Société 2008, 10, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomas-Maret, I.; Lewis, P.; Laforest, A.; Métivier, D.L. Localisation des activités métropolitaines: Quels impacts sur le navettage à Montréal? Environ. Urbain Urban Environ. 2011, 5, 38–51. [Google Scholar]

- Arbour, S.; Monrency, É. Les espaces économiques industriels spécialisés: Les patrons de mobilité des travailleurs et l’accessibilité en transport en commun. VertigO 2012, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiléra, A.; Mignot, D. Urban Sprawl, Polycentrism and Commuting. A Comparison of Seven French Urban Areas. Urban Public Econ. Rev. 2004, 1, 93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Helminen, V.; Rita, H.; Ristimäki, M.; Kontio, P. Commuting to the Centre in Different Urban Structures. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2012, 39, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartshorn, T.A.; Muller, P. Suburban Downtowns and the Transformation of Metropolitan Atlanta’s Business Landscape. Urban Geogr. 1989, 10, 375–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervero, R. America’s Suburban Centers: The Land Use-Transportation Link; Routledge: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Garreau, J. Edge City: Life on the New Frontier; Anchor: New York, NY, USA, 1991; p. 576. [Google Scholar]

- Coffey, W.; Drolet, R. Le Secteur Tertiaire et les Sièges Sociaux dans la Région Métropolitaine de Montréal; Étude Préparée pour le Bureau Fédéral de Développement Régional (Québec), Ed.; INRS-Urbanisation: Montréal, QC, Canada, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Stanback, T.M. The New Suburbanization: Challenge to the Central City; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Agyemang, F.S.K.; Silva, E.; Poku-Boansi, M. Understanding the urban spatial structure of Sub-Saharan African cities using the case of urban development patterns of a Ghanaian city-region. Habitat Int. 2019, 85, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz, I.; Garcia-López, M.À.; Galindo, A. The Effect of Employment Sub-centres on Population Density in Barcelona. Urban Stud. 2008, 45, 627–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berroir, S.; Mathian, H.; Sanders, L.; Saint-Julien, T. Les pôles de l’activité métropolitaine. In La Métropole Parisienne: Centralités, Inégalités, Proximités; Saint-Julien, T., Le Goix, R., Eds.; Belin: Paris, France, 2007; pp. 11–38. [Google Scholar]

- Yudhistira, M.H.; Indriyani, W.; Pratama, A.P.; Sofiyandi, Y.; Kurniawan, Y.R. Transportation network and changes in urban structure: Evidence from the Jakarta Metropolitan Area. Res. Transp. Econ. 2019, 74, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Maldonado, A.M.; Romein, A.; Verkoren, O.; Parente Paula Pessoa, R. Polycentric Structures in Latin American Metropolitan Areas: Identifying Employment Sub-centres. Reg. Stud. 2014, 48, 1954–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, M.; Bullivant, B.; Kanaroglou, P. Are major canadian city-regions monocentric, polycentric, or dispersed? Urban Geogr. 2017, 38, 445–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, J.; Trubka, R.; Kenworthy, J.; Newman, P. The role of urban form and transit in city car dependence: Analysis of 26 global cities from 1960 to 2000. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2014, 33, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arribas-Bel, D.; Sanz-Gracia, F. The validity of the monocentric city model in a polycentric age: US metropolitan areas in 1990, 2000 and 2010. Urban Geogr. 2014, 35, 980–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duvivier, C.; Polèse, M. The great urban techno shift: Are central neighbourhoods the next silicon valleys? Evidence from three Canadian metropolitan areas. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2018, 97, 1083–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duquet, B. Le centre-ville de Montréal est-il en perte de vitesse? Analyse de la localisation des services supérieurs 1996–2011. Can. Geogr. Le Géographe Can. 2018, 62, 505–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorra-Gobin, C. De la ville à l’urban sprawl: La question métropolitaine aux États-Unis. Cercles 2005, 13, 123–138. [Google Scholar]

- Terral, L.; Shearmur, R. Vers une nouvelle forme urbaine ? Desserrement et diffusion de l’emploi dans la région métropolitaine de Montréal. L’Espace Géographique 2008, 37, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulin, P.-O.; Shearmur, R. Quartiers durables et pôles d’emploi: Vers des navettes plus courtes et moins polluantes? Une analyse de Montréal, 1998–2008. Cah. Géographie Québec 2014, 58, 59–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salon, D. Neighborhoods, cars, and commuting in New York City: A discrete choice approach. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2009, 43, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weber, J. Individual accessibility and distance from major employment centers: An examination using space-time measures. J. Geogr. Syst. 2003, 5, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. Commuting Impacts of Spatial Decentralization: A Comparison of Atlanta and Boston. J. Reg. Anal. Policy 2005, 35, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Cervero, R.; Wu, K.-L. Sub-centring and Commuting: Evidence from the San Francisco Bay Area, 1980–1990. Urban Stud. 1998, 35, 1059–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, P.; Richardson, H.W. Beyond Polycentricity: The Dispersed Metropolis, Los Angeles, 1970–1990. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1996, 62, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, D. Accessibility and the journey to work. J. Transp. Geogr. 1998, 6, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schwanen, T.; Dieleman, F.; Dijst, M. Travel behaviour in Dutch monocentric and policentric urban systems. J. Transp. Geogr. 2001, 9, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervero, R. Jobs-Housing Balancing and Regional Mobility. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1989, 55, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, P.; Kumar, A.; Richardson, H. The Influence of Metropolitan Spatial Structure on Commuting Time. J. Urban Econ. 1989, 26, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, P.; Richardson, H.W.; Jun, M. The Commuting Paradox Evidence from the Top Twenty. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1991, 57, 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Choi, C. Towards Sustainable Urban Spatial Structure: Does Decentralization Reduce Commuting Times? Sustainability 2019, 11, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Katz, P.; Scully, V.J.; Bressi, T.W. The New Urbanism: Toward an Architecture of Community; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Calthorpe, P. The Next American Metropolis: Ecology, Community, and the American Dream; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Roy-Baillargeon, O. Le TOD contre la ville durable? Utiliser le transport collectif pour perpétuer le suburbanisme dispersé dans le Grand Montréal. Environ. Urbain Urban Environ. 2017, 12, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R. Is Los Angeles-Style Sprawl Desirable? J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1997, 63, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanen, T.; Dieleman, F.; Dijst, M. The Impact of Metropolitan Structure on Commute Behavior in the Netherlands: A Multilevel Approach. Growth Chang. 2004, 35, 304–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Næss, P. Urban form and travel behavior. Experience from a Nordic context. J. Transp. Land Use 2012, 5, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearmur, R.; Coffey, W.; Dube, C.; Barbonne, R. Intrametropolitan Employment Structure: Polycentricity, Scatteration, Dispersal and Chaos in Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver, 1996–2001. Urban Stud. 2007, 44, 1713–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, J.; Arnott, R.; Macdonald, J. Identifying Employment Subcenters: The Method of Exponentially Declining Cutoffs. Land 2017, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jun, M.-J. The effects of polycentric evolution on commute times in a polycentric compact city: A case of the Seoul Metropolitan Area. Cities 2020, 98, 102587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krehl, A.; Siedentop, S. Towards a typology of urban centers and subcenters-evidence from German city regions. Urban Geogr. 2019, 40, 58–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McMillen, D.P.; McDonald, J.F. Suburban Subcenters and Employment Density in Metropolitan Chicago. J. Urban Econ. 1998, 43, 157–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giuliano, G.; Small, K. Subcenters in the Los Angeles Region. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 1991, 21, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sultana, S.; Weber, J. The Nature of Urban Growth and the Commuting Transition: Endless Sprawl or a Growth Wave? Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 544–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J.F.; Prather, P.J. Suburban Employment Centres: The Case of Chicago. Urban Stud. 1994, 31, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, S.G.; Ng, P.T. Using Quantile Smoothing Splines to Identify Employment Subcenters in a Multicentric urban Area. J. Urban Econ. 2001, 49, 100–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murphy, R.E.; Vance, J.E. Delimiting the CBD. Econ. Geogr. 1954, 30, 189–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartshorn, T.A. Interpreting the City: An Urban Geography, 2nd ed.; J. Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley, D.; Kaza, N.; Lester, W. Are America’s Inner Cities Competitive? Evidence From the 2000s. Econ. Dev. Q. 2016, 30, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. New Strategies for Inner-City Economic Development. Econ. Dev. Q. 1997, 11, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillen, D.P.; Smith, S.C. The number of subcenters in large urban areas. J. Urban Econ. 2003, 53, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, T. Identification and Differentiation of Urban Centers in Phoenix Through a Multi-Criteria Kernel-Density Approach. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2010, 33, 205–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearmur, R.; Coffey, W. A tale of four cities: Intrametropolitan employment distribution in Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, and Ottawa-Hull, 1981–1996. Environ. Plan. A 2002, 34, 575–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appold, S. The Impact of Airports on US Urban Employment Distribution. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2015, 47, 412–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.; Knox, P. The New Metropolis: Rethinking Megalopolis. Reg. Stud. 2009, 43, 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey, W.; Shearmur, R. Agglomeration and Dispersion of High-order Service Employment in the Montreal Metropolitan Region, 1981–1996. Urban Stud. 2002, 39, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. Population des Régions Métropolitaines de Recensement. Government of Canada. Available online: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l02/cst01/demo05a-fra.htm (accessed on 10 May 2017).

- McMillen, D.P.; Lester, T.W. Evolving subcenters: Employment and population densities in Chicago, 1970–2020. J. Hous. Econ. 2003, 12, 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillen, D.P. Nonparametric employment subcenter identification. J. Urban Econ. 2001, 50, 448–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redfearn, C. The Topography of Metropolitan Employment: Identifying Centers of Employment in a Polycentric Urban Area. J. Urban Econ. 2007, 61, 519–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfister, N.; Freestone, R.; Murphy, P. Polycentricity or dispersion?: Changes in center employment in metropolitan Sydney, 1981 to 1996. Urban Geogr. 2000, 21, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogart, W.T.; Ferry, W.C. Employment Centres in Greater Cleveland: Evidence of Evolution in a Formerly Monocentric City. Urban Stud. 1999, 36, 2099–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, T.; Hartshorn, T.A. The Changing Metropolitan Structure of Atlanta, Georgia: Locations of Functions and Regional Structure in a Multinucleated Urban Area. Urban Geogr. 1995, 16, 680–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz, I.; Garcia-López, M.-À. The Polycentric Knowledge Economy in Barcelona. Urban Geogr. 2010, 31, 774–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinen, E.; Maat, K.; Wee, B.v. The role of attitudes toward characteristics of bicycle commuting on the choice to cycle to work over various distances. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2011, 16, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatkowski, D.; Krizek, K.; Handy, S. Accounting for the short term substitution effects of walking and cycling in sustainable transportation. Travel Behav. Soc. 2015, 2, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Charron, M.; Shearmur, R. Distances, interactions et analyse spatiale de la ville: Le cas de Montréal. Revue d’Économie Régionale Urbaine 2005, 163–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naud, D.; Apparicio, P.; Shearmur, R. Cogentrification sociale et économique: A colocalisation de la main-d’oeuvre et des emplois de services aux entreprises à Montréal, 1996–2001. Cah. Géographie Québec 2009, 53, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Axisa, J.; Scott, D.; Newbold, B. Factors influencing commute distance: A case study of Toronto’s commuter shed. J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 24, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filion, P.; Bunting, T.; Pavlic, D.; Langlois, P. Intensification and Sprawl: Residential Density Trajectories in Canada’s Largest Metropolitan Regions. Urban Geogr. 2010, 31, 541–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereitschaft, B. Gentrification and the evolution of commuting behavior within America’s urban cores, 2000–2015. J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 82, 102559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomonti, V. Politiques urbaines et mobilité durable: Analyse comparée d’Athènes et Amsterdam. Ecol. Polit. 2004, 29, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanen, T.; Dijst, M.; Dieleman, F.M. Policies for Urban Form and their Impact on Travel: The Netherlands Experience. Urban Stud. 2004, 41, 579–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Statistics Canada. Canadian Survey on Business Conditions: Impact of COVID-19 on Businesses in Canada, May 2020; The Daily: Ottawa, Canada, 2020.

- Merlin, P. La demande de transport: Analyse de la mobilité. In Les Transports à Paris et en Ile-de-France; Merlin, P., Ed.; La Documentation Française: Paris, France, 1982; pp. 41–130. [Google Scholar]

| CMA | Population | Jobs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 2016 | %∆ 1996–2016 | 1996 | 2016 | %∆ 1996–2016 | |

| Toronto, ON | 4,263,757 | 5,928,040 | 39.0% | 1,714,010 | 2,241,580 | 30.8% |

| Montreal, QC | 3,349,742 | 4,098,927 | 22.4% | 1,252,920 | 1,503,335 | 20.0% |

| Vancouver, BC | 1,831,665 | 2,463,431 | 34.5% | 646,125 | 839,375 | 29.9% |

| Calgary, AB | 822,221 | 1,392,609 | 69.4% | 319,620 | 524,845 | 64.2% |

| Quebec City, QC | 679,036 | 800,296 | 17.9% | 248,790 | 320,070 | 28.7% |

| Winnipeg, MA | 672,109 | 778,489 | 15.8% | 246,250 | 288,500 | 17.2% |

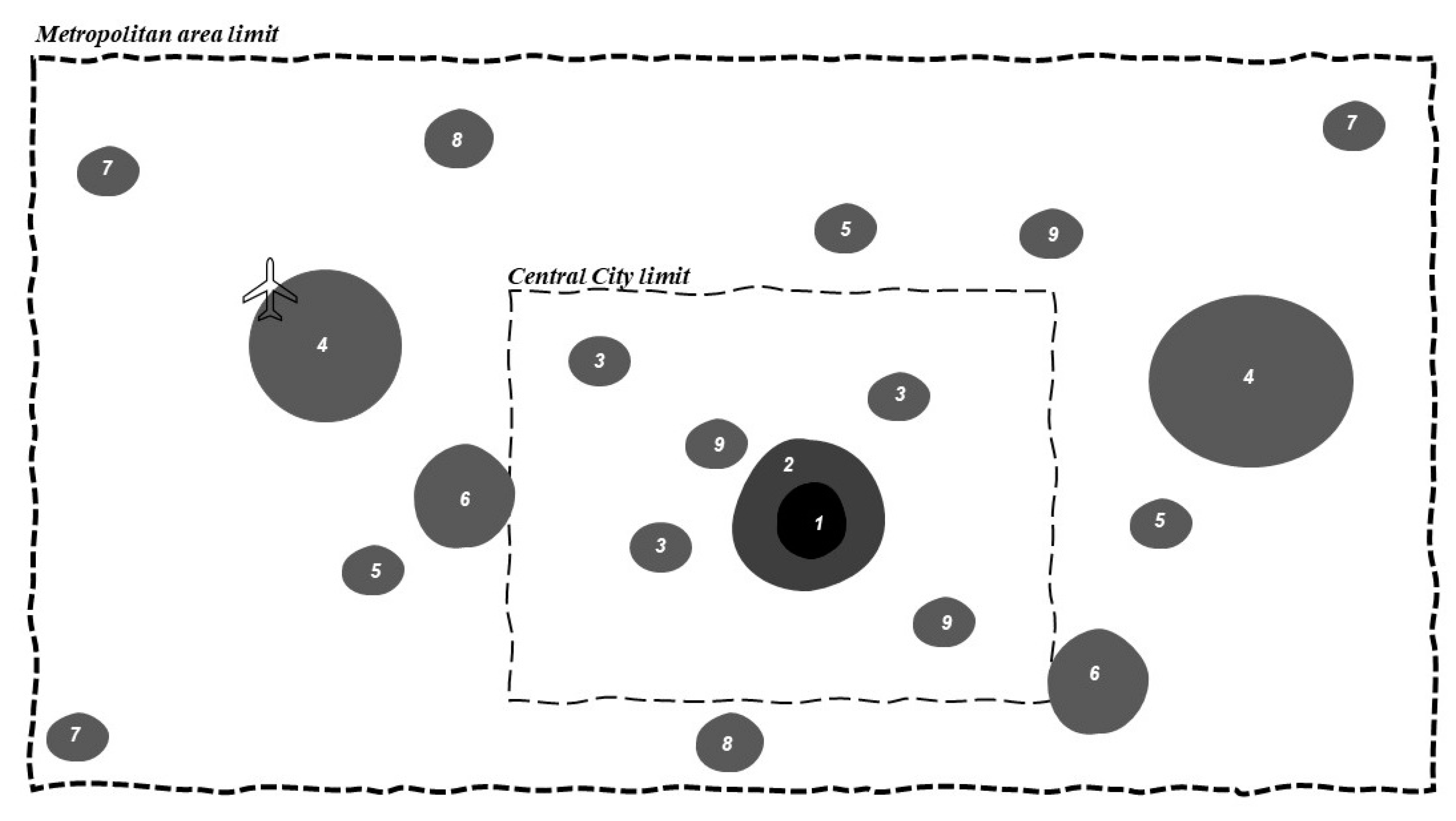

| # | Type of Subcentres | Attributes for Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver | Attributes for Calgary, Quebec City, and Winnipeg | Predominant Variable(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Downtown | 1 | CBD area | Identified as CBD | Identified as CBD | Distance from the CBD |

| 2 | Downtown area (without CBD) | Vicinity of the CBD | Vicinity of the CBD | Distance from the CBD | |

| Subcentres | 3 | Inner city subcentres | Subcentres near to the CBD (between 3.4 km to 6.3 km 1) within a medium-to-high residential and job density | Subcentres near to the CBD (between 1.9 km to 6.3 km 2) | Distance from the CBD and Residential density |

| 4 | Primary subcentres and Airports | Airport area and large growing subcentres (between 26 k and 241 k jobs) with medium-to-high job density | Airport area and large growing subcentres (between 20 k and 82 k jobs) | Number of jobs | |

| 5 | Small subcentres | - | Less large growing subcentres (above 12 k jobs) | Number of jobs | |

| 6 | Non-distant subcentres with medium-to-high density | Less large growing subcentres (8 k to 19 k jobs) not so far from the CBD (8.9 km to 23 km) | - | Job and Residential density, and Distance from the CBD | |

| 7 | Distant subcentres with low density | Far subcentres (more than 18 km), within low residential and jobs density | - | Distance from the CBD and Job density | |

| 8 | Boom centres | Subcentres that have doubled their number of jobs between 1996 and 2016 | Subcentres that have doubled their number of jobs between 1996 and 2016 | Employment growth | |

| 9 | Declining subcentres | Subcentres that have lost jobs | Subcentres that have lost jobs | Employment growth |

| 1996 | 2016 | ∆ 1996–2016 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMA | Subcentres | Small Subcentres | Total | Subcentres | Small Subcentres | Total | |

| Toronto | 9 | 10 | 19 | 8 | 9 | 17 | −2 |

| Montreal | 8 | 1 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 16 | +7 |

| Vancouver | 7 | 12 | 19 | 16 | 7 | 23 | +4 |

| Calgary | 4 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 10 | +6 |

| Quebec City | 4 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 7 | +1 |

| Winnipeg | 2 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 8 | +1 |

| CBD | Subcentres | Largest Subcentres | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ 1996–2016 | p-Value | Δ 1996–2016 | p-Value | Δ 1996–2016 | p-Value | |

| TOR | − | 0.798 | + | 0.000 | + | 0.000 |

| MTL | − | 0.063 | + | 0.011 | + | 0.064 |

| VAN | − | 0.494 | + | 0.300 | − | 0.000 |

| CGY | + | 0.000 | + | 0.000 | + | 0.000 |

| QC | − | 0.821 | + | 0.000 | + | 0.000 |

| WPG | + | 0.000 | + | 0.000 | + | 0.000 |

| Subcentres Type | Mean Differences and t-Tests | |

|---|---|---|

| Δ 1996–2016 | p-Value | |

| CBD | + | 0.000 |

| Downtown area | + | 0.000 |

| Inner city subcentres | + | 0.000 |

| Primary subcentres and Airports | + | 0.000 |

| Boom centres | + | 0.000 |

| Declining subcentres | + | 0.000 |

| Non-distant subcentres with medium-to-high density | + | 0.000 |

| Distant subcentres with low density | − | 0.000 |

| Small subcentres | + | 0.000 |

| Inner City Subcentres | Distant Subcentres with Low Density | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ 1996–2016 | p-Value | Δ 1996–2016 | p-Value | |

| TOR | − | 0.629 | + | 0.122 |

| MTL | − | 0.332 | + | 0.175 |

| VAN | + | 0.000 | − | 0.000 |

| CGY | + | 0.000 | n/a | n/a |

| QC | + | 0.000 | n/a | n/a |

| WPG | + | 0.000 | n/a | n/a |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duquet, B.; Brunelle, C. Subcentres as Destinations: Job Decentralization, Polycentricity, and the Sustainability of Commuting Patterns in Canadian Metropolitan Areas, 1996–2016. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9966. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239966

Duquet B, Brunelle C. Subcentres as Destinations: Job Decentralization, Polycentricity, and the Sustainability of Commuting Patterns in Canadian Metropolitan Areas, 1996–2016. Sustainability. 2020; 12(23):9966. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239966

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuquet, Benjamin, and Cédric Brunelle. 2020. "Subcentres as Destinations: Job Decentralization, Polycentricity, and the Sustainability of Commuting Patterns in Canadian Metropolitan Areas, 1996–2016" Sustainability 12, no. 23: 9966. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239966

APA StyleDuquet, B., & Brunelle, C. (2020). Subcentres as Destinations: Job Decentralization, Polycentricity, and the Sustainability of Commuting Patterns in Canadian Metropolitan Areas, 1996–2016. Sustainability, 12(23), 9966. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239966