Increasing Personnel Competencies in Museums with the Use of Auditing and Controlling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Modern Museums

2.2. HR Management

3. Material and Methodology

3.1. Auditing

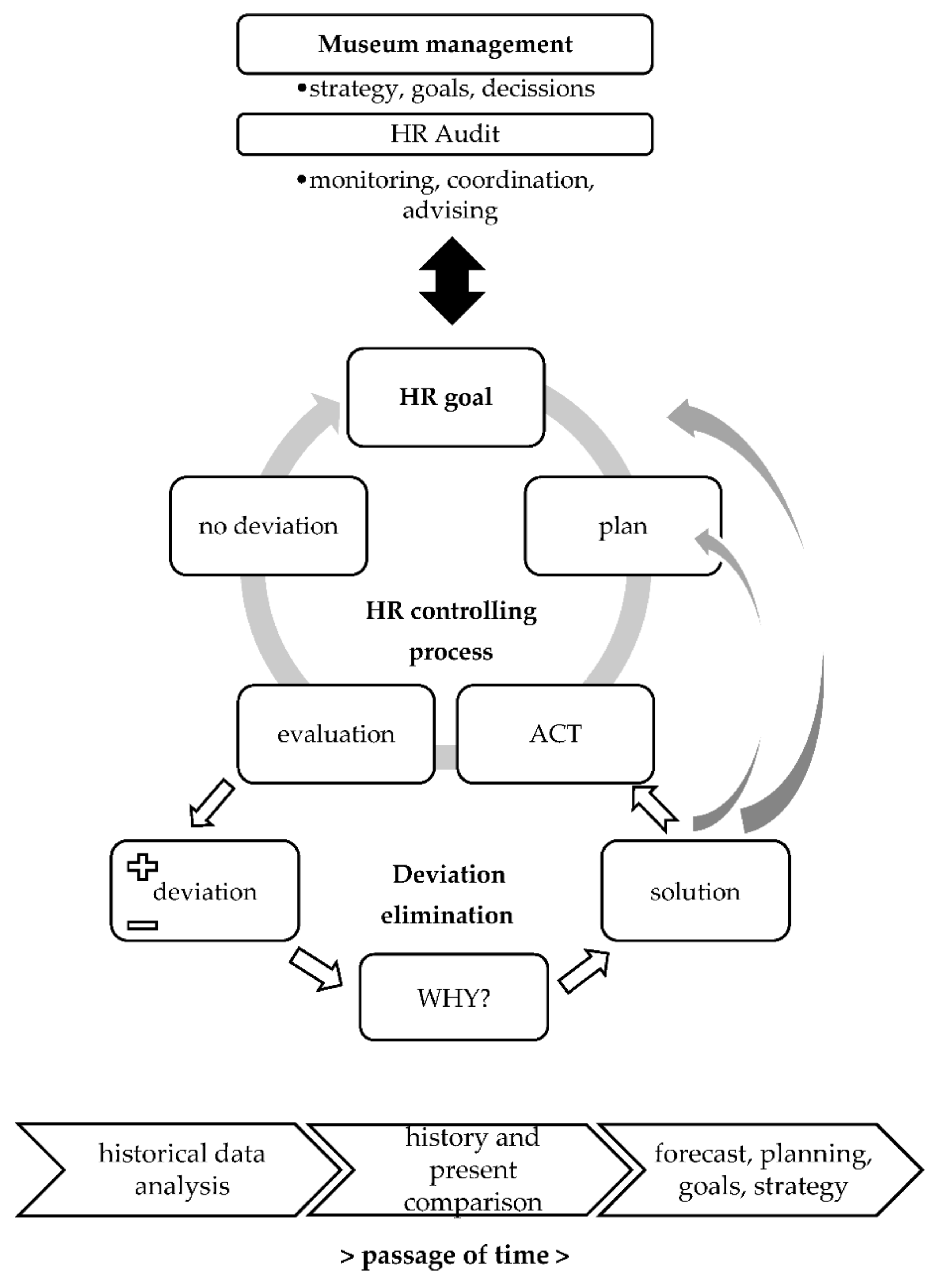

3.2. Controlling

3.3. Methodology

4. Computing and Results Interpretation

4.1. Model Interpretation

4.2. HR Auditing and HR Controlling Process

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Pearson Variables Correlations

| Visit. Analys. | HR Comm. | Employe Quantity | Pers. Comp. | Orga. Cult. | QM | ERP Analys | HR Audit | MTG Activity | HR Cont. | Social net. | Exist. Years | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit. analys. | Pear. Corr. | 1 | 0.283 ** | 0.201 ** | 0.365 ** | 0.225 ** | 0.225 ** | 0.258 ** | 0.287 ** | 0.190 ** | 0.273 ** | 0.213 ** | −0.064 |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.071 | ||

| N | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | |

| HR comm. | Pear. Corr. | 0.283 ** | 1 | 0.340 ** | 0.731 ** | 0.697 ** | 0.571 ** | 0.654 ** | 0.629 ** | 0.541 ** | 0.742 ** | 0.155 ** | 0.050 |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.154 | ||

| N | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | |

| Employe quantity | Pear. Corr. | 0.201 ** | 0.340 ** | 1 | 0.492 ** | 0.417 ** | 0.512 ** | 0.444 ** | 0.401 ** | 0.307 ** | 0.503 ** | 0.086 * | 0.040 |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.015 | 0.257 | ||

| N | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | |

| Pers. comp. | Pear. Corr. | 0.365 ** | 0.731 ** | 0.492 ** | 1 | 0.659 ** | 0.686 ** | 0.770 ** | 0.780 ** | 0.549 ** | 0.799 ** | 0.152 ** | 0.058 |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.099 | ||

| N | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | |

| Orga. culture | Pear. Corr. | 0.225 ** | 0.697 ** | 0.417 ** | 0.659 ** | 1 | 0.566 ** | 0.650 ** | 0.612 ** | 0.516 ** | 0.683 ** | 0.066 | 0.055 |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.061 | 0.120 | ||

| N | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | |

| QM | Pear. Corr. | 0.225 ** | 0.571 ** | 0.512 ** | 0.686 ** | 0.566 ** | 1 | 0.609 ** | 0.629 ** | 0.556 ** | 0.761 ** | 0.076 * | 0.035 |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.030 | 0.324 | ||

| N | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | |

| ERP analys | Pear. Corr. | 0.258 ** | 0.654 ** | 0.444 ** | 0.770 ** | 0.650 ** | 0.609 ** | 1 | 0.656 ** | 0.441 ** | 0.718 ** | 0.057 | 0.042 |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.102 | 0.234 | ||

| N | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | |

| HR Audit | Pear. Corr. | 0.287 ** | 0.629 ** | 0.401 ** | 0.780 ** | 0.612 ** | 0.629 ** | 0.656 ** | 1 | 0.488 ** | 0.687 ** | 0.096 ** | 0.089 * |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.011 | ||

| N | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | |

| MTG activity | Pear. Corr. | 0.190 ** | 0.541 ** | 0.307 ** | 0.549 ** | 0.516 ** | 0.556 ** | 0.441 ** | 0.488 ** | 1 | 0.710 ** | 0.161 ** | 0.012 |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.728 | ||

| N | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | |

| HR Contrg. | Pear. Corr. | 0.273 ** | 0.742 ** | 0.503 ** | 0.799 ** | 0.683 ** | 0.761 ** | 0.718 ** | 0.687 ** | 0.710 ** | 1 | 0.157 ** | 0.057 |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.106 | ||

| N | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | |

| Social networks | Pear. Corr. | 0.213 ** | 0.155 ** | 0.086 * | 0.152 ** | 0.066 | 0.076 * | 0.057 | 0.096 ** | 0.161 ** | 0.157 ** | 1 | 0.054 |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.015 | 0.000 | 0.061 | 0.030 | 0.102 | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.127 | ||

| N | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | |

| Exist. years | Pear. Corr. | −0.064 | 0.050 | 0.040 | 0.058 | 0.055 | 0.035 | 0.042 | 0.089 * | 0.012 | 0.057 | 0.054 | 1 |

| Sig. | 0.071 | 0.154 | 0.257 | 0.099 | 0.120 | 0.324 | 0.234 | 0.011 | 0.728 | 0.106 | 0.127 | ||

| N | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | |

References

- Bira, M.; Zbuchea, A.; Romanelli, M. Romanian Museums under Scrutiny. Manag. Dyn. Knowl. Econ. 2020, 8, 297–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batrancea, L.; Nichita, A.; Batrancea, I.; Cesar, A.M.R.V.C.; Forte, D. Sustainable tax behavior on future and current emerging markets: The case of Romania and Brazil. Sustain. Soc. Responsib. Account. Rep. Syst. 2018, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerquetti, M.; Ferrara, C. Marketing Research for Cultural Heritage Conservation and Sustainability: Lessons from the Field. Sustainability 2018, 10, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.; Guizzardi, A. Does Designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site Influence Tourist Evaluation of a Local Destination? J. Travel Res. 2019, 59, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajili, K.; Lin, L.Y.-H.; Rostamkalaei, A. Corporate governance, human capital resources, and firm performance. J. Gen. Manag. 2020, 45, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pencarelli, T.; Cerquetti, M.; Splendiani, S. The sustainable management of museums: An Italian perspective. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 22, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowska, B.; Lulek, A. Management of Manufacturing Resources in an Enterprise on the Example of Human Resources. Acta Sci. Pol. Oeconomia 2020, 19, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đurković, J.V.; Nikolić, I.; Matović, I.M. Human Resource Management in the Function of Improving the Quality of Banks’ Business as a Support in Financing Agriculture in Serbia. Econ. Agric. Ekon. Poljopr. 2020, 67, 781–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, D.N. Augmented human-centered management Human resource development for highly automated business environments. J. HRM 2020, 23, 13–27. Available online: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=886798 (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Furtună, C.; Ciucioi, A. Internal Audit in the Era of Continuous Transformation. Survey of Internal Auditors in Romania. Audit. Financiar. 2019, 17, 452–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunget, O.C.; Brînduşe, A.I. Connection Between Controlling Department and Management-Premise for Achieving Organizational Objectives. Audit. Financiar. 2019, 17, 680–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffaelli, M.; Armstrong, J.; Tran, S.P.; Griffith, A.N.; Walker, K.; Gutierrez, V. Focus on Methodology: Beyond paper and pencil: Conducting computer-assisted data collection with adolescents in group settings. J. Adolesc. 2016, 49, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, N. Základy Sociální Psychologie; Portál: Praha, Czech Republic, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. Sociologie; Argo: Praha, Czech Republic, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wijayatunga, P. A geometric view on Pearson’s correlation coefficient and a generalization of it to non-linear dependencies. Ratio Math. 2016, 30, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainelli, F.; Manetti, G.; Sibilio, B. Web-based accountability practices in non-profit organizations: The case of national museums. Voluntas 2013, 24, 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marstine, J. Cultural equity in the sustainable museum: Tristam Besterman. In The Routledge Companion to Museum Ethics; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; pp. 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Švec, M.; Horecký, J.; Madleňák, A. GDPR in Labour Relations–with or without the Consent of the Employee? Ad Alta J. Interdiscip. Res. 2018, 8, 281–286. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, N.G.; Kotler, P.; Kotler, W.I. Museum Marketing and Strategy; John Wiley and Sons: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tajtáková, M. Marketing Kultúry. Ako Osloviť a Udržať si Publikum; Eurokódex: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lukáč, M.; Mihálik, J. Data Envelopment Analysis–a Key to the Museum’s ‘Secret Chamber’ of Marketing? Commun. Today 2018, 9, 106–117. Available online: https://www.communicationtoday.sk/download/22018/08.-LUKAC-MIHALIK-E28093-CT-2-2018.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Hayton, B. Sustainability and public museum buildings–The UK legislative perspective. Stud. Conserv. 2010, 55, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbuchea, A. Museums as Theme Parks—A Possible Marketing Approach? Manag. Dyn. Knowl. Econ. 2015, 3, 483–507. Available online: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=596295 (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Johnová, R.; Černá, J. Arts Marketing–Marketing Umění a Kulturního Dědictví; Oeconomica: Praha, Czech Republic, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeven, A. Networked practices of intangible urban heritage: The changing public role of Dutch heritage professionals. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2019, 25, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOM. Code of Ethics for Museums; ICOM: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://icom.museum/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ICOM-code-En-web.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- ButoracováŠ-indleryová, I.; Benková, E. The Theory of City Marketing Conception and Its Dominance in the Tourism Regional Development. Hotel. Link 2009, 10, 389–396. [Google Scholar]

- Komarac, T.; Ozretic-Dosen, D.; Skare, V. Understanding competition and service offer in museum marketing. Acad. Rev. Latinoam. Adm. 2017, 30, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batrancea, L.; Nichita, A.; Batrancea, I.; Gaban, L. The strength of the relationship between shadow economy and corruption: Evidence from a worldwide country-sample. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 138, 1119–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachova, K.; Stacho, Z.; Raišienė, A.G.; Barokova, A. Human resource management trends in Slovakia. J. Int. Stud. 2020, 13, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janes, R.R.; Sandell, R. Posterity Has Arrived. The Necessary Emergence of Museum Activism. Museum Activism; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Viganó, F.; Lombardo, G. Calculating the Social Impact of Culture. A SROI application in a Museum. In International and Interdisciplinary Conference on Digital Environments for Education, Arts and Heritage; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2018; pp. 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Messersmith, J. On the shoulders of giants: A meta-review of strategic human resource management. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 6–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinokur-Kaplan, D. Workplace Attitudes, Experiences, and Job Satisfaction of Social Work Administrators in Nonprofit and Public Agencies: 1981 and 1989. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 1996, 25, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, C.; Ichiho, R.; Anderson, V. Understanding level 5 leaders: The ethical perspectives of leadership humility. J. Manag. Dev. 2017, 36, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigli, M.; Panagiotopoulos, G.; Argyropoulou, M. Managing and Developing Human Resources at the Museum: Modern Trend or Quality Upgrade? Qual. Quant. Methods Libr. 2019, 8, 1. Available online: http://www.qqml-journal.net/index.php/qqml/article/view/507 (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Bohlouli, M.; Mittas, N.; Kakarontzas, G.; Theodosiou, T.; Angelis, L.; Fathi, M. Competence assessment as an expert system for human resource management: A mathematical approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 70, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usiaevaa, A.; Rubtcovaa, M.; Pavlenkovaa, I.; Petropavlovskayab, S. Sociological Diagnostics in Staff Competency Assessments: Evidence from Russian Museums. Int. J. Prod. Manag. Eng. 2016, 4, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowar-Sulej, K. Human resources development as an element of sustainable HRM–with the focus on production engineers. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrů, N.; Pavlák, M.; Polák, J. Factors impacting startup sustainability in the Czech Republic. Innov. Mark. 2019, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacho, Z.; Stachová, K.; Raišienė, A.G. Change in approach to employee development in organizations on a regional scale. J. Int. Stud. 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobl, A.; Mussner, T.; Niedermair, J.; Matzler, K. Triggering subordinate innovation behavior: The influence of leaders’ dark personality traits and level 5 leadership behavior. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2019, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, B.P.; Hekman, D.R. Modeling how to grow: An inductive examination of humble leader behaviors, contingencies and outcomes. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 787–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blštáková, J.; Joniaková, Z.; Jankelová, N.; Stachová, K.; Stacho, Z. Reflection of Digitalization on Business Values: The Results of Examining Values of People Management in a Digital Age. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, D.M.; Niculina, D.; Alexe, G.A. Performance Indicators in Museum Institutions from the Three Es Perspective (Economy, Efficiency, Effectiveness). Ovidius Univ. Ann. Ser. Econ. Sci. 2012, 12, 653–658. Available online: http://stec.univ-ovidius.ro/html/anale/ENG/cuprins%20rezumate/volum2012p1.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Madleňák, A.; Žulová, J. The Right to Privacy in the Context of the Use of Social Media and Geolocation Services; Wolters Kluwer: Budapest, Hungary, 2019; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Bożek, S.; Emerling, I. Protecting the Organization Against Risk and the Role of Financial Audit on the Example of the Internal Audit. Oeconomia Copernic. 2016, 7, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitru, M.I.; Burtescu, C. Offences and Penalties in the Internal Audit Activity. Sci. Bull. Econ. Sci. 2015, 14, 36–44. Available online: https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:pts:journl:y:2015:i:2:p:36-44 (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Basu, S.K. Auditing: Principles and Techniques; Pearson Education: New Delhi, India, 2007; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Putnová, A.; Seknička, P. Etické Řízení ve Firmě; Grada Publishing: Praha, Czech Republic, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Müllerová, L. Auditing pro Manažery aneb Proč a Jak se Ověřuje Účetní Závěrka; Wolters Kluwer: Praha, Czech Republic, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- IIA. Definition of Internal Auditing. 2020. Available online: https://na.theiia.org/standards-guidance/mandatory-guidance/Pages/Definition-of-Internal-Auditing.aspx (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Xhani, N.; Avram, M.; Meçe, I.; Çela, L. Comparative Study on the Organization of Internal Public Audit in Albania and Romania. Audit. Financiar. 2019, 17, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laval, V. How to Increase the Value-Added of Controlling; Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2018; p. 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, S.K.H. The Internal Auditing Handbook, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2010; p. 1088. [Google Scholar]

- Kupec, V. Risk Audit of Marketing Communication. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2018, XXI, 125–132. Available online: https://www.ersj.eu/dmdocuments/2018_XXI_1_11.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2020). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mahoney, J.T.; Kor, Y.Y. Advancing the human capital perspective on value creation by joining capabilities and governance approach. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 29, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieliaieva, N. International practice of the concepts use of “HR audit”, “staff audit”, “personnel audit”. Econ. Ecol. Socium 2019, 3, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karjalainen, J.; Niskanen, M.; Niskanen, J. The effect of audit partner gender on modified audit opinions. Int. J. Audit. 2018, 22, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, R.R. COSO Enterprise Risk Management: Establishing Effective Governance, Risk, and Compliance, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2011; p. 384. [Google Scholar]

- Macintosh, N.N.; Quattrone, P. Management Accounting and Control Systems; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Varanini, F.; Ginevri, W. Projects and Complexity; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kamps, T. Systematic Chasing for Economic Success: An Innovation Management Approach; Anchor: Hamburg, Germany, 2013; p. 120. [Google Scholar]

- Benedic, N.O. The Challenge of Controlling. Int. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2015, 6, 153–163. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/293814491_The_Challenge_of_Controlling (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Písař, P.; Kupec, V. Innovative Controlling and Audit–Opportunities for SMEs. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2019, 17, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Písař, P.; Bílková, D. Controlling as a tool for SME management with an emphasis on innovations in the context of Industry 4.0. Q. J. Econ. Econ. Policy 2019, 14, 763–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlugoš, I. Personnel Controlling, an Integral Part of Human Resource Management of Industrial Enterprises. Soc. Econ. Rev. 2013, 11, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kruliš, J. How to Win the Risks; Linde: Praha, Czech Republic, 2011; p. 558. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, K.J.; Salomon, R.M. Capabilities, contractual hazards, and governance: Integrating resource-based and transaction cost perspectives. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 942–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endovitskaya, E.V. The introduction of personnel control in processing organizations: Features of the process approach. Vestn. Voronežskogo Gos. Univ. Inženernyh Tehnol. 2020, 81, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Břečková, P.; Havlíček, K. Leaders Management and Personnel Controlling in SMEs. Eur. Res. Stud. 2013, 16, 3–13. Available online: https://is.vsfs.cz/publication/3769/cs (accessed on 19 October 2020). [CrossRef]

- Dvorský, J.; Petráková, Z.; Polách, J. Assessing the Market, Financial and Economic Risk Sources by Czech and Slovak SMEs. Int. J. Entrep. Knowl. 2019, 7, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A. Risk Management and Simulation; CRC Press: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kupec, V.; Lukáč, M.; Štarchoň, P.; Pajtinková Bartáková, G. Audit of Museum Marketing Communication in the Modern Management Context. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2020, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikušová, M. To be or not to be a business responsible for sustainable development? Survey from small Czech businesses. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraživanja 2019, 30, 1318–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, F.J. Survey Research Methods; Center for Survey Research: Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, R.; Mileva, M.; Ritchie, K.L. Inter-rater Agreement in Trait Judgements from Faces. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsintsadze, A.; Oniani, L.; Ghoghoberidze, T. Determining and Predicting Correlation of Macroeconomic Indicators on Credit Risk Caused by Overdue Credit. Banks Bank Syst. 2018, 13, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chornous, G.; Ursulenko, G. Risk management in banks: New approaches. Ekonomika 2013, 92, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M. Robustness of Two Formulas to Correct Pearson Correlation for Restriction of Range; Georgia State University: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Darlington, R.B.; Hayes, A.F. Regression Analysis and Linear Models: Concepts, Applications, and Implementation; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McCall, V.; Gray, C. Museums and the ‘new museology’: Theory, practice and organizational change. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2014, 29, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kor, Y.; Mahoney, J.T. How dynamics, management, and governance of resource deployments influence firm level performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrů, N.; Kramoliš, J.; Stuchlík, P. Marketing tools in the era of digitization and their use in practice by family and other businesses. Econ. Manag. 2020, 23, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batrancea, L.; Nichita, A.; Olsen, J.; Kogler, C.H.; Kirchler, E.; Hoelzl, E.; Weiss, A.; Torgler, B.; Fooken, J.; Fuller, J.; et al. Trust and power as determinants of tax compliance across 44 nations. J. Econ. Psychol. 2019, 74, 102191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fronzetti, C.; Grippa, A.F.; Innarella, R. Studying the Association of Online Brand Importance with Museum Visitors: An Application of the Semantic Brand Score. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednárik, J. Change of paradigm in personnel strategy-corporate social responsibility and internal communication. Commun. Today 2019, 10, 42–56. Available online: https://www.communicationtoday.sk/wp-content/uploads/04.-BEDNARIK-%E2%80%93-CT-2-2019.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Al-Waely, D. The Impact of Careful Application of Growth Management Policies and Sustainable Development on the Changing Marketing Environment. Eur. J. Econ. Stud. 2019, 8, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Réklaitis, K.; Pileliené, L. Principle Differences between B2B and B2C Marketing Communication Processes. Manag. Organ. Syst. Res. 2019, 81, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosacka-Olejnik, M.; Pitakaso, R. Industry 4.0: State of the art and research implications. LogForum 2019, 15, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ployhart, R.E.; Nyberg, A.J.; Reilly, G.; Maltarich, M.A. Human capital is dead; long live human capital resources! J. Manag. 2014, 40, 371–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Concept | Hypotheses Question | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | General | N/Y | How long has the museum been in operation in years? |

| Q2 | H2 | How many employees does the museum have? | |

| Q3 | HR | H3 | Does the museum use HR (Human Resource) Auditing? |

| Q4 | H3 | Does the museum use HR Controlling? | |

| Q5 | H4 | Does the museum put emphasis on HR communication? | |

| Q6 | KPI | H1 | Does the museum regularly evaluate the employee/visitors ratio? |

| Q7 | H1 | Does the museum put emphasis on organizational (internal) culture? | |

| Q8 | H1 | Does the museum put emphasis on (QM) ERP * analysis? | |

| Q9 | H1 | Does the museum use ERP * (information system) for efficiency analysis? | |

| Q10 | H1 | Do you think that the museum is performing well in marketing activities? | |

| Q11 | H1 | Does the museum put emphasis on social media activities? | |

| Q12 | H1-4 | Does the museum continuously develop personnel competencies? | |

| Q13 | H1 | Does the museum regularly evaluate the employee/visitors ratio? | |

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 0.457 | 0.071 | 6.445 | 0.000 | |

| HR Controlling | 1.109 | 0.029 | 0.799 | 37.736 | 0.000 | |

| 2 | (Constant) | 0.026 | 0.065 | 0.402 | 0.688 | |

| HR Controlling | 0.692 | 0.034 | 0.498 | 20.125 | 0.000 | |

| HR Auditing | 0.594 | 0.034 | 0.437 | 17.658 | 0.000 | |

| 3 | (Constant) | −0.054 | 0.064 | −0.853 | 0.394 | |

| HR Controlling | 0.526 | 0.040 | 0.379 | 13.226 | 0.000 | |

| HR Auditing | 0.531 | 0.034 | 0.391 | 15.858 | 0.000 | |

| HR communication | 0.261 | 0.034 | 0.203 | 7.600 | 0.000 | |

| 4 | (Constant) | −0.194 | 0.062 | −3.102 | 0.002 | |

| HR Controlling | 0.321 | 0.045 | 0.231 | 7.191 | 0.000 | |

| HR Auditing | 0.402 | 0.033 | 0.296 | 12.226 | 0.000 | |

| HR communication | 0.184 | 0.032 | 0.143 | 5.674 | 0.000 | |

| Visitors analysis | 0.108 | 0.019 | 0.096 | 5.703 | 0.000 | |

| ERP analysis | 0.082 | 0.030 | 0.069 | 2.719 | 0.007 | |

| ERP analysis | 0.305 | 0.030 | 0.249 | 10.000 | 0.000 | |

| 5 | (Constant) | −0.257 | 0.065 | −3.960 | 0.000 | |

| HR Controlling | 0.299 | 0.045 | 0.215 | 6.664 | 0.000 | |

| HR Auditing | 0.400 | 0.033 | 0.295 | 12.243 | 0.000 | |

| HR communication | 0.195 | 0.032 | 0.152 | 6.017 | 0.000 | |

| Visitors analysis | 0.104 | 0.019 | 0.092 | 5.490 | 0.000 | |

| Quality management | 0.061 | 0.030 | 0.052 | 1.999 | 0.046 | |

| ERP analysis | 0.293 | 0.031 | 0.239 | 9.607 | 0.000 | |

| Employees quantity | 0.066 | 0.020 | 0.063 | 3.278 | 0.001 | |

| Model | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Std. Error of the Estimate | Change Statistics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R Square Change | F Change | df1 | df2 | Sig. F Change | |||||

| 1 | 0.799 a | 0.638 | 0.638 | 0.875 | 0.638 | 1424.043 | 1 | 808 | 0.000 |

| 2 | 0.860 b | 0.739 | 0.738 | 0.744 | 0.101 | 311.815 | 1 | 807 | 0.000 |

| 3 | 0.870 c | 0.756 | 0.755 | 0.719 | 0.017 | 57.756 | 1 | 806 | 0.000 |

| 4 | 0.891 d | 0.794 | 0.793 | 0.662 | 0.038 | 49.682 | 3 | 803 | 0.000 |

| 5 | 0.893 e | 0.797 | 0.795 | 0.658 | 0.003 | 10.746 | 1 | 802 | 0.001 |

| Model | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Regression | 1091.062 | 1 | 1091.062 | 1424.043 | 0.000 b |

| Residual | 619.067 | 808 | 0.766 | |||

| Total | 1710.128 | 809 | ||||

| 2 | Regression | 1263.596 | 2 | 631.798 | 1141.824 | 0.000 c |

| Residual | 446.532 | 807 | 0.553 | |||

| Total | 1710.128 | 809 | ||||

| 3 | Regression | 1293.454 | 3 | 431.151 | 834.005 | 0.000 d |

| Residual | 416.674 | 806 | 0.517 | |||

| Total | 1710.128 | 809 | ||||

| 4 | Regression | 1358.686 | 6 | 226.448 | 517.403 | 0.000 e |

| Residual | 351.442 | 803 | 0.438 | |||

| Total | 1710.128 | 809 | ||||

| 5 | Regression | 1363.333 | 7 | 194.762 | 450.406 | 0.000 f |

| Residual | 346.796 | 802 | 0.432 | |||

| Total | 1710.128 | 809 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kupec, V.; Lukáč, M.; Písař, P.; Gubíniová, K. Increasing Personnel Competencies in Museums with the Use of Auditing and Controlling. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10343. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410343

Kupec V, Lukáč M, Písař P, Gubíniová K. Increasing Personnel Competencies in Museums with the Use of Auditing and Controlling. Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10343. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410343

Chicago/Turabian StyleKupec, Václav, Michal Lukáč, Přemysl Písař, and Katarína Gubíniová. 2020. "Increasing Personnel Competencies in Museums with the Use of Auditing and Controlling" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10343. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410343

APA StyleKupec, V., Lukáč, M., Písař, P., & Gubíniová, K. (2020). Increasing Personnel Competencies in Museums with the Use of Auditing and Controlling. Sustainability, 12(24), 10343. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410343