An Exploratory Study on Social Entrepreneurship, Empowerment and Peace Process. The Case of Colombian Women Victims of the Armed Conflict

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- -

- How does social entrepreneurship contribute to the empowerment of women victims of the Colombian armed conflict?

- -

- How does the empowerment of women victims of the conflict contribute to the peace process?

2. Social Entrepreneurship as an Alternative to Female Empowerment

2.1. Female Economic Empowerment and Entrepreneurship

2.2. Social Entrepreneurship

3. Social Entrepreneurship as a Promoter of the Economic Empowerment of Women Victims of the Colombian Armed Conflict and the Construction of Peace

3.1. Social Entrepreneurship and Empowerment of Female Victims

3.2. Social Entrepreneurship and the Peace Processes

4. Female Social Entrepreneurship in Colombia

4.1. The General Context of Colombia

4.2. The Conflict and Colombian Women Today

4.3. The Woman Victim of the Conflict and the Possibility of Entrepreneurship in Colombia

5. Exploratory Empirical Study

5.1. Research Methodology

5.2. Findings

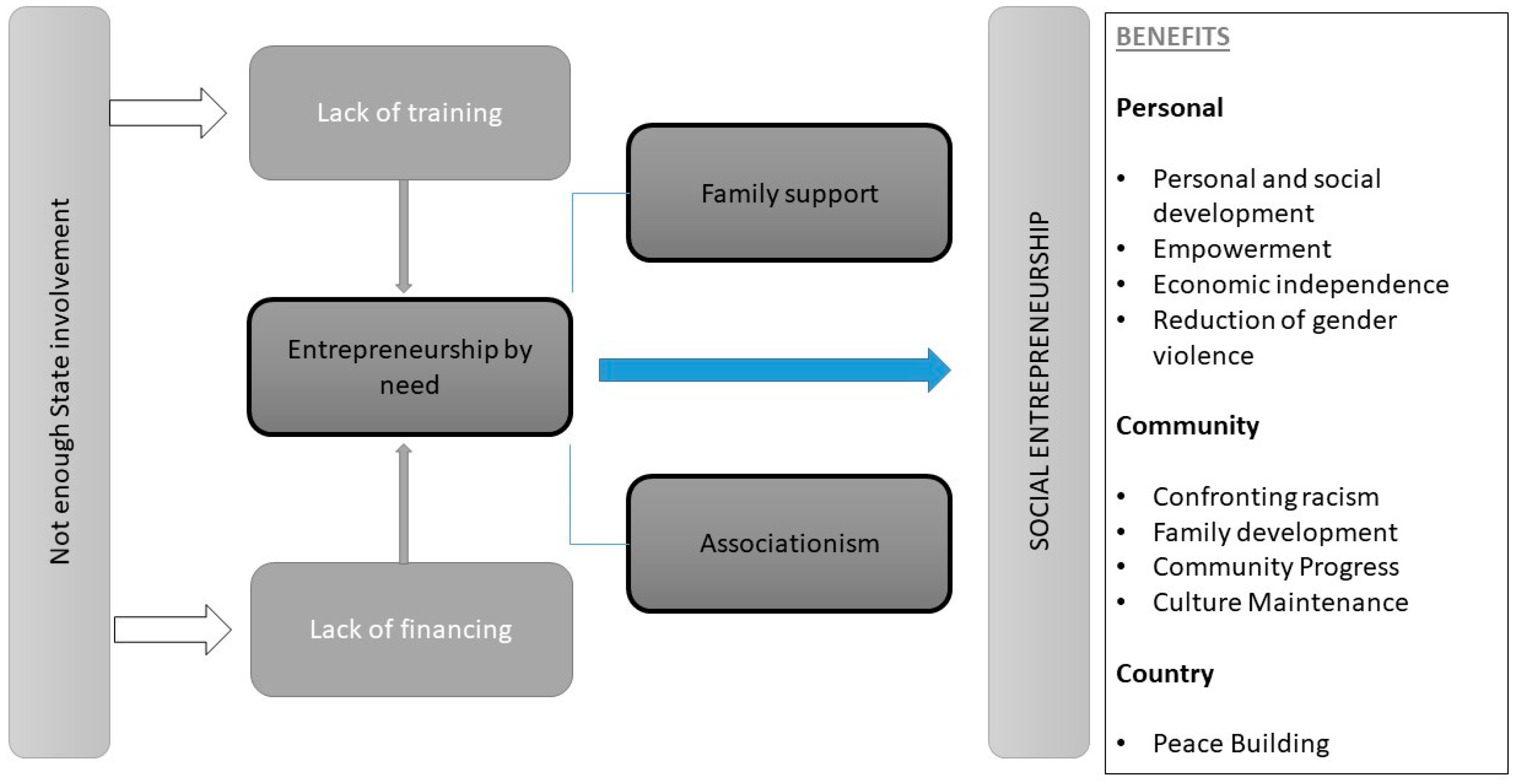

5.2.1. Entrepreneurship Out of Necessity

5.2.2. Insufficient Presence of the State. The Problems of Financing and Training

5.2.3. Female Persistence

5.2.4. By and for the Social Field. Family Support

5.2.5. Union as a Tool

5.2.6. Supporting Culture

5.2.7. Development, Independence and Social Self-Realization

5.2.8. Fight against Gender Violence and Racism

5.2.9. Building Peace

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN Women. (n.d.). Qué Hacemos: Empoderamiento Económico. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/es/what-we-do/economic-empowerment (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Tovar-Restrepo, M.; Irazábal, C. Indigenous Women and Violence in Colombia. Agency, Autonomy, and Territoriality. Lat. Am. Perspect. 2014, 41, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croce, F. Indigenous women entrepreneurship: Analysis of a promising research theme at the intersection of indigenous entrepreneurship and women entrepreneurship. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2019, 43, 1013–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amnesty International. Violence Against Indigenous Women and Girls in Canada: A Summary of Amnesty International’s Concerns and Call to Action. Ottawa. Available online: https://www.amnesty.ca/sites/amnesty/files/iwfa_submission_amnesty_international_february_2014_-_final.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Human Rights Watch. Informe Mundial 2020 Sobre Derechos Humanos en el Mundo. 2020. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/es/world-report/2020/country-chapters/336672#dcdee0 (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- VeneKlaseny, L.; Miller, V. A New Weave of Power, People and Politics: The Action Guide for Advocacy and Citizen Participation; World Neighbors: Oklahoma City, OK, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardini, S.; Bowman, K.; Garwood, R. A ‘How to Guide to Measuring Women’s Empowerment: Sharing Experience from Oxfam’s Impact Evaluations; Oxfam: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brandão, E.A.F.; Santos, T.R.; Rist, S. Connecting Public Policies for Family Farmers and Women’s Empowerment: The Case of the Brazilian Semi-Arid. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbi, M.S.D.; Dhakal, N.H.; Hijazi, S.T. Nepal and Pakistan: Micro-Finance and Microenterprise Development: Their Contribution to The Economic Empowerment of Women; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/empent/Publications/WCMS_111397/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 21 October 2020).

- Hunter, B.A.; Jason, L.A.; Keys, C.B. Factors of empowerment for women in recovery from substance use. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 2013, 51, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Galindo-Reyes, F.C.; Ciruela-Lorenzo, A.M.; Pérez-Moreno, S.; Pérez-Canto, S. Rural indigenous women in Bolivia: A development proposal based on cooperativism. Women Stud. Int. Forum 2016, 59, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Vashista, N.; Siddique, R.A. Women empowerment through entrepreneurship for their holistic development. Asian J. Res. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2017, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, G. Role of social entrepreneurs in women empowerment and indigenous people development: A cross-case analysis. J. Asia Entrep. Sustain. 2020, 16, 106–161. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.; Varma, S.K. Women empowerment through entrepreneurial activities of Self Help Groups. Indian J. Ext. Educ. 2008, 8, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Dua, S.; Hatwal, V. Micro enterprise development and rural women entrepreneurship: Way for economic empowerment. Arth Prabhand J. Econ. Manag. 2012, 1, 114–127. [Google Scholar]

- Torri, M.C.; Martínez, A. Women’s empowerment and micro-entrepreneurship in India: Constructing a new development paradigm? Prog. Dev. Stud. 2014, 14, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederman, D.; Messina, J.; Pienknagura, S.; Rigolini, J. El Emprendimiento en América Latina: Muchas Empresas y Poca Innovación. Banco Mundial. 2014. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/LAC/EmprendimientoAmericaLatina_resumen.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Morris, M.; Kuratko, D.; Covin, J.G. Corporate Entrepreneurship & Innovation; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Urbano, D.; Jiménez, E.F.; Noguera, M.N. Female social entrepreneurship and socio-cultural context: An international analysis. Rev. Estud. Empres. 2014, 2, 26–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chica, M.F.; Posso, M.I.; Montoya, J.C. Importancia del Emprendimiento Social en Colombia. Doc. de Trab. ECACEN 2017, 2. Available online: https://hemeroteca.unad.edu.co/index.php/working/article/view/1915 (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Ospina, A. Emprendimiento social como alternativa para la solución de problemas personales y sociales en Colombia. Rev. Investig. Cient. Tecnol. 2019, 3, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullough, A.; Renko, M.; Myatt, T. Danger zone entrepreneurs: The importance of resilience and self-efficacy for entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep. Theory Pr. 2014, 38, 473–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, M. Peace through access to entrepreneurial capitalism for all. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, S. Trading for peace. Econ. Policy 2018, 33, 485–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Chauhan, S.; Paul, J.; Jaiswal, M.P. Social entrepreneurship research: A review and future research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 113, 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, D.H.; Kaciak, E.; Shamah, R. Determinants of women entrepreneurs’ firm performance in a hostile environment. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 88, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, N.; Majumdar, S. Social entrepreneurship as ana essentially contested concept: Opening a new avenue for systematic future research. J. Bus. Ventur. 2014, 29, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacin, P.; Dacin, M.; Matear, M. Social entrepreneurship: Why we don’t need a new theory and how we move forward from here. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2010, 24, 37–57. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, P.B.; Gailey, R. Empowering women through social entrepreneurship: Case study of a women’s cooperative in India. Entrep. Theory Pr. 2012, 36, 569–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugh, H.M.; Talwar, A. Linking Social Entrepreneurship and Social Change: The Mediating Role of Empowerment. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 133, 643–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maguirre, M.; Ruelas, G.C.; Torre, C.G. Women empowerment through social innovation in indigenous social enterprises. RAM. Rev. Adm. Mackenzie 2016, 17, 164–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Constantin, P.-N.; Stanescu, R.; Stanescu, M. Social Entrepreneurship and Sport in Romania: How Can Former Athletes Contribute to Sustainable Social Change? Sustainability 2020, 12, 4688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa Karki, S.; Xheneti, M. Formalising women entrepreneurs in the informal economy of Kathmandu, Nepal: Pathway towards empowerment? Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2018, 38, 526–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, S.; Ojha, S.N.; Ramasubramanian, V.; Vipinkumar, V.P.; Ananthan, P.S. Entrepreneurship based empowerment among fisherwomen self help groups of Kerala. Indian J. Fish. 2017, 64, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kapoor, S. Entrepreneurship for economic and social empowerment of women: A case study of a self help credit program in Nithari Village, Noida, India. Australas. Account. Bus. Financ. J. 2019, 13, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. Gender equality and women’s empowerment: A critical analysis of the third Millennium Development Goal. Gend. Dev. 2005, 13, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröcklin, S.; Jiddawi, N.S.; De la Torre-Castro, M. Small-scale innovations in coastal communities: Shell-handicraft as a way to empower women and decrease poverty. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciancaglini, M.I. El Empoderamiento Económico de las Mujeres a Través de los Emprendimientos Como Oportunidad de Desarrollo. 2016. Available online: https://www.eoi.es/blogs/msoston/2016/03/09/el-empoderamiento-economico-de-las-mujeres-a-traves-de-los-emprendimientos-como-oportunidad-de-desarrollo/ (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Banco de Desarrollo de América Latina. Available online: https://www.caf.com/es/actualidad/noticias/2018/03/en-america-latina-los-productos-financieros-no-estan-pensados-para-las-mujeres/ (accessed on 28 February 2020).

- Padilla-Mélendez, A.; Ciruela-Lorenzo, A.M. Female indigenous entrepreneurs, culture, and social capital. The case of the Quechua community of Tiquipaya (Bolivia). Women Stud. Int. Forum 2018, 69, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, K.; Scriver, S. Dangerously empty? Hegemony and the construction of the Irish entrepreneur. Organization 2012, 19, 615–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, B.K. Learning from interacting: Language, economics and the entrepreneur. Horizon 2014, 22, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toca, C. Consideraciones para la formación en emprendimiento: Explorando nuevos ámbitos y posibilidades. Estud. Gerenc. 2010, 26, 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Azqueta, A. El concepto de emprendedor: Origen, evolución e introducción, Simposio Internacional El Desafío de Emprender en la Escuela del Siglo XXI, Sevilla, España. 2017. Available online: https://idus.us.es/handle/11441/74177 (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Bravo, M. Las escuelas de pensamiento del emprendimiento social. TEC Empres. 2016, 10, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N.; Chakrabarti, R.; Prabhu, J.C.; Brem, A. Managing dilemmas of resource mobilization through jugaad: A multi-method study of social enterprises in Indian healthcare. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2020, 14, 419–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dees, G.; Anderson, B. Framing a theory of social entrepreneurship: Building on two schools of practice and thought. In Research on Social Entrepreneurship: Understanding and Contributing to an Emerging Field; ARNOVA: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2007; pp. 39–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kickul, J.; Lyons, T.S. Understanding Social Entrepreneurship: The Relentless Pursuit of Mission in an Ever Changing World; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein, D. Como Cambiar el Mundo: El Poder de los Emprendedores Sociales; Limperfraf: Barcelona, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, J.G.; Herrera, J.M.; Oliveros, J.A.; Estefan, M.; Muñoz, J.A.; Pascagaza, Y.M.; Cantillo, N.; Pedraza, C. Prospectiva del Emprendimiento Social y Solidario. Retos y Desafíos para la Construcción Social de Territorios de Futuro; Universidad Nacional Abierta y a Distancia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2014; Available online: https://repository.unad.edu.co/handle/10596/7391 (accessed on 5 July 2020).

- Fischel, A. Cómo Educar en Emprendedurismo Social y ética. Congreso Internacional de Emprendedurismo Social, Universidad Nacional de Costa Rica, Costa Rica. 2013. Available online: http://www.redunes.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Congreso-Emprendedurismo-Social-Ponencia-Astrid.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2020).

- Zahra, S.A.; Rawhouser, H.N.; Bhawe, N.; Neubaum, D.O.; Hayton, J.C. Globalization of social entrepreneurship opportunities. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2008, 2, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, J.; Twersky, F. New Social Entrepreneurs: The Success, Lessons, and Challenge of Non-Profit Enterprise Creation. Roberts Enterprise Development Fund. 1996. Available online: https://community-wealth.org/sites/clone.community-wealth.org/files/downloads/report-redf96-intro.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- Wallace, S.L. Social entrepreneurship: The role of social purpose enterprises in facilitating community economic development. J. Dev. Entrep. 1999, 4, 153. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, D.M. Stimulating social entrepreneurship: Can support from cities make a difference? Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2007, 21, 77–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.; Urriolagoitia, L. El emprendimiento social. Rev. Española Terc. Sect. 2011, 17, 17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gramm, V.; Dalla Torre, C.; Membretti, A. Farms in Progress-Providing Childcare Services as a Means of Empowering Women Farmers in South Tyrol, Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cáceres, R.; Ramos, L.E. Emprendimiento Laboral y Empoderamiento de las Mujeres Artesanas de la Asociación de Tejedoras “Tejidos Huaycán”. Tesis de licenciatura, Universidad Nacional del Centro de Perú, Huancayo, Perú, 2017. Available online: http://repositorio.uncp.edu.pe/handle/UNCP/3410 (accessed on 22 December 2019).

- García, F.; Navarro, R.D.; Spíndola, F.; Tapia, I. Emprendimiento Social y Empoderamiento de la Mujer Rural Indígena en la Sierra Norte de Puebla: Caso del Hotel Taselotzin; Ibero Puebla: San Andrés Cholula, Mexico, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Legis, T.E. Social Entrepreneurship Factors Influencing Women Empowerment in Kajiado County, Kenya. Doctoral Thesis, United States International University-Africa, Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. Available online: http://41.204.183.105/handle/11732/6021 (accessed on 22 December 2019).

- Castiblanco, S. Género y Trabajo: Un Análisis del Empoderamiento de los Emprendedores y Emprendedoras de Subsistencia de Bogotá. Tesis de maestría, Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia, 2015. Available online: https://repositorio.uniandes.edu.co/bitstream/handle/1992/12915/u703890.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Allen, E.; Elman, A.; Langowitz, N.; Dean, M. Report on Women and Entrepreneurship; Babson College, Center for Women´s Leadership: Wellesley, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bosma, N.; Acs, Z.; Autio, E.; Coduras, A.; Levie, J. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2008 Executive Report; Babson College and Global Entrepreneurship Research Consortium: Babson Park, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Buendía-Martínez, I.; Carrasco, I. Mujer, actividad emprendedora y desarrollo rural en América Latina y el Caribe. Cuad. Desarro. Rural 2013, 10, 21–45. [Google Scholar]

- Platzek, B.P.; Pretorius, L. Regional cooperation in a thriving entrepreneurial economy: A holistic view on innovation, entrepreneurship and economic development. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2020, 17, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN (United Nations). Improvement of the Situation of Women in Rural Areas. Report of the Secretary General, Sixtieth Session, A/60/165. 2005. Available online: https://www.iom.int/jahia/webdav/shared/shared/mainsite/policy_and_research/un/60/A_60_165_en.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2020).

- Formichella, M. El Concepto de Emprendimiento y su Relación con la Educación, el Empleo y el Desarrollo Local; Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria: Avenida Rivadavia, Argentina, 2004. Available online: http://municipios.unq.edu.ar/modules/mislibros/archivos/MonografiaVersionFinal.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2020).

- Ahmad, N.; Seymour, R.G. Defining entrepreneurial activity: Definitions supporting frameworks for data collection. In OECD Statistics Working Papers; No. 2008/01; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosca, E.; Agarwal, N.; Brem, A. Women entrepreneurs as agents of change: A comparative analysis of social entrepreneurship processes in emerging markets. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2020, 157, 120067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundación Ideas para la Paz, ONU Mujeres y Pacto Global Red Colombia. Empresas, empoderamiento económico de las mujeres y construcción de paz. 2016. Available online: http://cdn.ideaspaz.org/media/website/document/58471492b237b.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Cruz, F. Empoderamiento y participación social de la mujer en el medio rural. La perspectiva de género en el desarrollo rural. Agric. Fam. España 2009, 110–115. Available online: https://www.upa.es/anuario_2009/pag_110-115_fatimacruz.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Drucker, P. Escritos Fundamentales; Random House Mondadori: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Mendoza, J.A.; Avendaño-Castro, W.R.; Rueda-Vera, G. Perceptions of the Colombian business sector regarding its role in the post-conflict. Cuad. Adm. 2019, 35, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, E.J. Social mobilization and violence in civil war and their social legacies. In The Oxford Handbook of Social Movements; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 452–467. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, K.; Chen, C.; Beardsley, K. Conflict, Peace, and the Evolution of Women’s Empowerment. Int. Organ. 2019, 73, 255–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- González, J. Empresa privada: Principal socio en el posconflicto y la construcción de la paz. Panorama 2016, 10, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Esteve, J. Los Principios Rectores sobre las empresas transnacionales y los derechos humanos en el marco de las Naciones Unidas para «proteger, respetar y remediar»: ¿hacia la responsabilidad de las corporaciones o la complacencia institucional? Anu. Esp. Derecho Int. 2011, 27, 315–349. [Google Scholar]

- International Alert. Las Empresas Locales y la Paz: El Potencial de Construcción de Paz del Sector Empresarial Nacional; International Alert: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lederach, J.P. Building Peace: Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies; Institute of Peace Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, S.; Ozkazanc-Pan, B. Feminist perspectives on social entrepreneurship: Critique and new directions. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2016, 8, 221–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, C.; Hampson, F.; Aall, P. Turbulent Peace: The Challenges of Managing International Conflict; United States Institute of Peace Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés, J. Emprendimiento, Instituciones y Construcción de Paz en el Noroccidente de Boyacá. Available online: https://www.urosario.edu.co/Escuela-de-Administracion/Investigacion/Documentos/Emprendimiento-Instituciones-y-CP-en-el-NO-de-Boya.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Oficina de Estudios Económicos. Contexto macroeconómico de Colombia. Ministerio de Comercio, Industria y Turismo. Available online: https://www.mincit.gov.co/getattachment/1c8db89b-efed-46ec-b2a1-56513399bd09/Colombia.aspx (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- CEPAL-Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe. Perfil Nacional Económico de Colombia; CEPAL-Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe: Santiago, Chile, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- DANE—Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística. Gran encuesta integrada de hogares. Available online: https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/mercado-laboral/empleo-y-desempleo/geih-historicos (accessed on 8 January 2020).

- UNHCR—Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Information Note on Colombia and Murders of Rights Activists. 2020. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/SP/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=25825&LangID=S (accessed on 11 October 2020).

- PNUD—Programa de Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo. Informe Sobre el Desarrollo Humano 2019. Desigualdades del desarrollo humano en el siglo XXI. 2020. Available online: https://www.co.undp.org/content/colombia/es/home/library/human_development/informe-sobre-desarrollo-humano-2019.html (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Martínez Montoya, R.; Bello Ramírez, A.; Michelle del Pino, A.; Bermúdez Pérez, H.N.; Serrano Murcia, A.M. La Guerra Inscrita en el Cuerpo: Informe Nacional de Violencia Sexual en el Conflicto Armado; Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica: Bogotá, Colombia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gallego Zapata, M. La verdad de las mujeres. Víctimas del conflicto armado en Colombia. Edita Ruta Pacífica de las Mujeres, Bogotá. 2013. Available online: https://www.aecid.es/Centro-Documentacion/Documentos/Publicaciones%20coeditadas%20por%20AECID/La%20verdad%20de%20la%20mujeres%20(Tomo%201).pdf (accessed on 2 February 2020).

- Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica. Balance del Conflicto Armado, 1958–2018. Observatorio de Memoria y Conflicto. Available online: http://centrodememoriahistorica.gov.co/observatorio/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/General_15-09-18.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Andrade, J.A.; Barranco, L.; Jiménez, L.K.; Redondo, M.P.; Rodríguez, L. La vulnerabilidad de la mujer en la guerra y su papel en el posconflicto. El Ágora USB 2017, 17, 290–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrando, E.P. Movilización Social por la paz: Las Luchas del Movimiento de Mujeres en Colombia. Las Mujeres en la Movilización Social por la paz (1982–2017); Data-paz, CINEP: Bogotá, Colombia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, M.A.; Rojas, N. El rol de la mujer en el conflicto armado colombiano. El Libre Pensador 2015, 1–32. Available online: https://librepensador.uexternado.edu.co/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2015/10/El-rol-de-la-mujer-en-el-conflicto-armado-colombiano-Maestr%C3%ADa-en-gobierno-y-pol%C3%ADticas-p%C3%BAblicas-El-Libre-Pensador.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- Ros, J.M. El concepto de la democracia en Alexis de Tocqueville: Una lectura filosófico-politica de la democracia en América. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Jaume I, Castellón, Spain, 2000. Available online: https://www.tdx.cat/bitstream/handle/10803/10451/ros.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 2 February 2020).

- Escobar, R.A. Las ONG como organizaciones sociales y agentes de transformación de la realidad: Desarrollo histórico, evolución y clasificación. Diálogos Saberes Investig. Cienc. Soc. 2010, 32, 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, A.; Trujillo, M.A. Emprendimiento social: Revisión literaria. Estud. Gerenc. 2008, 24, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Acosta, B.V.; Suárez, M.; Zambrano, S.M. Emprendimiento femenino y ruralidad en Boyacá, Colombia. Criterio Libre 2017, 15, 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arias, A.; Henríquez, M.C.; Mosquera, C.E. La creación de empresas en Colombia desde las percepciones femenina y masculina. Revis Econ. Gest. Desarro. 2010, 10, 61–77. [Google Scholar]

- ONU Mujeres Colombia. El Progreso de las Mujeres en Colombia 2018: Transformar la Economía para Realizar los Derechos. 2018. Available online: https://lac.unwomen.org/es/digiteca/publicaciones/2018/10/el-progreso-de-las-mujeres-en-colombia (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Zamora, L.F. El Estado Colombiano ante el Emprendimiento en Clave de Género. Master’s Thesis, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- CECODES—Concejo Empresarial para el Desarrollo Sostenible. Negocios Inclusivos—Una Estrategia Empresarial para Reducir la Pobreza: Avances y Lineamientos. Available online: http://bibliotecavirtualrs.com/2011/04/negocios-inclusivos-una-estrategia-empresarial-para-reducir-la-pobreza/ (accessed on 28 September 2020).

- Hernández, H.G.; Jiménez, A.; Pitre, P. Emprendimiento social y su repercusión en el desarrollo económico desde los negocios inclusivos. LogosC&T 2018, 10, 198–211. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manage. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M.; Sköldberg, K. Reflexive Methodology—New Vistas for Qualitative Research; Sage: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Method, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, J.A. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, S. Citizenship’s place: The state’s creation of public space and street vendors’ culture of informality in Bogota, Colombia. Environ. Plann. D 2009, 27, 331–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solarte, M.L.S.; Solarte, C.M.S. Entrepreneurship in the Colombia-Ecuador Border Integration Zone in the Post-Conflict Setting. J. Environ. Treat. Tech. 2020, 3, 1182–1190. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, S.; Lenka, U. An exploratory study on the development of women entrepreneurs: Indian cases. J. Res. Mark. Entrep. 2016, 18, 232–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, R.; Luck, F.; Kraus, S.; Walsh, S. On the motivational drivers of gray entrepreneurship: An exploratory study. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2014, 89, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmen, M.; Min, T.; Saarelainen, E. Female entrepreneurship in Afghanistan. J. Dev. Entrep. 2011, 16, 307–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twinn, S. An exploratory study examining the influence of translation on the validity and reliability of qualitative data in nursing research. J. Adv. Nurs. 1997, 26, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wally, E.; Koshy, S. The use of Instagram as a marketing tool by Emirati female entrepreneurs: An exploratory study. In Proceedings of the 29th International Business Research Conference, World Business Institute Australia, Sydney, Australia, 17 October 2014; pp. 1–19. Available online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/dubaipapers/621 (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Wang, Q. Gender, race/ethnicity, and entrepreneurship: Women entrepreneurs in a US south city. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 1766–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Lenka, U.; Singh, K.; Agrawal, V.; Agrawal, A.M. A qualitative approach towards crucial factors for sustainable development of women social entrepreneurship: Indian cases. J. Clean Prod. 2020, 274, 123135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, R.E. Qualitative Research Studying How Things Work; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gaber, J. Qualitative Analysis for Planning & Policy: Beyond the Numbers; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Miles Matthew, B.; Michael Huberman, A. An Expanded Sourcebook Qualitative Data Analysis; No. 300.18 M5; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D. Analyzing talk and text. Handb. Qual. Res. 2000, 2, 821–834. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.L. Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, G.W.; Bernard, H.R. Techniques to identify themes. Field Method 2003, 15, 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ACNUR. Tendencias Globales. Desplazamiento Forzado en. 2019. Available online: https://www.acnur.org/5eeaf5664#_ga=2.14987377.67393784.1602496408-1407090733.1602496408 (accessed on 5 March 2020).

- Molina-Giraldo, E. Factores de riesgo y consecuencias de la violencia de género en Colombia. Tempus Psicológico 2019, 2, 14–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GEM—Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. 2018/2019 Women’s Entrepreneurship Report. Available online: https://www.gemconsortium.org/file/open?fileId=50405 (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Montgomery, A.W.; Dacin, P.A.; Dancin, M.T. Collective social entrepreneurship: Collaboratively shaping social good. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Interviewed | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 49 | 59 | 47 | 43 | 65 | 49 | 57 |

| Department | Quindío | Cauca | Cauca Valley | Caldas | Bogotá D.C. | Bogotá D.C. | Putumayo |

| Civil Status | Single | Single | Married | Single | Widow | Widow | Married |

| Ethnicity | Mixed race | Afro-Colombian | Afro-Colombian | Mixed race | Afro-Colombian | Pijao indigenous | Mixed race |

| Kind of Violence | Forced displacement and threats | Victim and victim’s family | Stigmatization by ethnicity and place of origin | Forced displacement | Persecution and violation | Forced displacement | Forced displacement |

| Children and Dependents | Both | Both | Both | Both | Children | Both | Both |

| Studies | Secondary | Secondary | Secondary | Higher | Basic | Basic | Higher |

| Main Activity | Food products | Textile products and accessories | Hair products | Food products | Food products | Food products | Gastronomy |

| Question Idea | Thought of the Most Frequent Answer | Percentage of Women Who Share This Thought |

|---|---|---|

| Reason why you decided to start a business | I am a victim of the conflict and it was my only possible option. | 100% (7/7) |

| Greater difficulties to undertake for women than for men | It is more difficult to get the initial financing and it is also more difficult to maintain and grow | 100% (7/7) |

| Support from the Colombian government or other institutions | We have obtained financing and help from relatives or our own savings and from some friends and acquaintances, but the government does not help and it is very difficult to get bank loans | 71% (5/7) |

| Meaning for you of entrepreneurship on a personal level | I have grown as a person and it has helped me face difficult situations in a better way. | 100% (7/7) |

| Meaning for you of entrepreneurship at a professional level | It has allowed me to have economic independence and meet other entrepreneurs who have helped each other | 86% (6/7) |

| The work of women (social entrepreneurship) benefits the development of their community and country | Female entrepreneurship contributes economically and with jobs but, in addition, it serves as an example to other women and satisfies some of their needs | 100% (7/7) |

| The work of women contributes to the achievement of peace | With our contribution and participation, we go from victims to protagonists of change. We have to participate to achieve a society with less discrimination. | 100% |

| Associations necessary for the future of the activities of women entrepreneurs | It is very important, because that way we grow faster and, in addition, there is mutual help and more solidarity between us. | 71% (5/7) |

| Socio-political participation of women | Entrepreneurship makes us more visible, and this presence increases more and more, but there is still a long way to go | 86% (6/7) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ciruela-Lorenzo, A.M.; González-Sánchez, A.; Plaza-Angulo, J.J. An Exploratory Study on Social Entrepreneurship, Empowerment and Peace Process. The Case of Colombian Women Victims of the Armed Conflict. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10425. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410425

Ciruela-Lorenzo AM, González-Sánchez A, Plaza-Angulo JJ. An Exploratory Study on Social Entrepreneurship, Empowerment and Peace Process. The Case of Colombian Women Victims of the Armed Conflict. Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10425. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410425

Chicago/Turabian StyleCiruela-Lorenzo, Antonio Manuel, Ana González-Sánchez, and Juan José Plaza-Angulo. 2020. "An Exploratory Study on Social Entrepreneurship, Empowerment and Peace Process. The Case of Colombian Women Victims of the Armed Conflict" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10425. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410425