Abstract

This study examines the conditions under which dual commitments to competing institutional logics, particularly a social vs. a commercial logic, are both important to organizational functioning for social enterprises. Using hand-collected data from a survey of 190 social enterprises in South Korea, we identify a reliable measure for the sustainability of competing logics. We also identify the factors associated with variation in a social enterprise’s capacity to sustain dual commitments to competing institutional logics. Using an imprinting perspective, we show that a social entrepreneur’s non-profit experience has a curvilinear effect on the sustainability of competing logics. Moreover, the non-linear effect of a social entrepreneur’s non-profit experience on the sustainability of competing logics is less profound in social enterprises with a highly ambivalent founder.

1. Introduction

Social enterprises have received growing popularity [1,2,3,4]. In particular, organization theorists have applied the lens of institutional logic—the socially constructed, historical patterns of material practices, assumptions, values, beliefs, and rules [5] (p. 69)—to describe social enterprises as hybrid organizations and defined them as enterprises that combine multiple institutional logics inside the organization [6,7,8,9,10,11]. Contrary to pure businesses or pure charities, social enterprises are inherently designed to sustain commitments to both competing institutional logics: a social welfare logic, which guided their activities to interact with public social services, and a commercial logic, which led them to rely on commercial customers and industrial partners in order to survive [8,12,13]. Therefore, emphasis of the research on social entrepreneurship has centered around the topic of how to sustain the dual imperatives while managing tensions when social enterprises commit to competing institutional logics [14,15,16,17].

To date, extensive research has mainly focused on organization-level solutions for sustaining commitments to competing institutional logics inside organizations. For example, having separate policies [18], conforming the minimum standards of distinct logics [19], developing a new organizational identity [6], applying performance measurement system [20], and implementing an innovative business model [21] have been identified. These studies have significantly advanced our understanding of management practices to integrate competing institutional logics with minimal tensions; however, little attention was paid to the role of a decision maker who ultimately combines competing logics and manages tensions over time when facing institutional logics’ complexity [22].

Because a decision maker makes sense of complex situations [23], experiences different levels of conflicts [24], and determines priorities of organizations [25]; a social entrepreneur, as a decision maker in a social enterprise, is recognized as being crucial to the varying degree of commitments to competing logics, ranging from relatively equal incorporation to a prioritization of one logic over another [26,27]. Therefore, scholars have argued that better understanding of a social entrepreneurial organization’s sustainability of competing institutional logics requires more systematic investigation of the background or attributes of a social entrepreneur [28,29]. Hence, this study aims to identify and examine the relevant background of a social entrepreneur, which can directly influence the sustainability of dual commitments to competing institutional logics. We also explore the moderating role of a social entrepreneur’s attributes associated with cognitive structure in contributing to the sustainability of competing logics.

This paper offers three contributions. First, we add to research on social entrepreneurship by juxtaposing an institutional logics and imprinting perspective. According to the imprinting perspective, organizations are shaped by the context at the time of founding. We develop and test hypotheses about how and to what extent the sustainability of competing institutional logics in a social entrepreneurial organization is imprinted by a social entrepreneur. In this regard, our research extends the few recent studies that delved into the relationship between organizational hybridity and heterogeneity of social entrepreneurs [22,28,29,30]. Second, we add to the imprinting literature by offering the effects of non-profit experience, as a salient experience of social entrepreneurs on managing competing demands. Furthermore, we argue that the role of a social entrepreneur’s non-profit experience in the sustainability of competing logics may depend on cognitive-related attributes that she or he possesses. Third, this research contributes to the literature by collecting and utilizing novel quantitative data to tackle underexplored constructs and relationships constrained by lack of an instrument or data. We not only offer a validated instrument to measure the sustainability of commitments to competing logics, but also provide empirical evidence based on large-scale data. Therefore, this research can offer useful guidance for scholars interested in conducting empirical research on sustainability of competing logics in social enterprises.

We have organized this study as follows. First, we explore how a social entrepreneur could impact the sustainability of competing logics, based on an imprinting perspective. Second, we not only identify non-profit experience as a possible attribute enhancing sustainability, but we also hypothesize that there is a curvilinear relationship between it and the sustainability of competing logics. Third, we hypothesize that an ambivalent interpretation and career variety play moderating roles in the proposed curvilinear relationship. Fourth, we explain the methodology, including its empirical setting, data collection, operationalization of the variables, and statistical analysis. Finally, we interpret the results and discuss their theoretical and practical implications.

2. Imprinting Perspective: Role of a Social Entrepreneur

We presume that social entrepreneurs play a key role in determining the sustainability of dual commitments to competing logics. One way to examine their possible influence is from an imprinting perspective. Stinchcombe [31] described organizational structures as reflections of the environment based on the industrial conditions from when an organization was founded. In other words, the founding conditions appear to have a long-lasting impact on the strategy, structure, and processes of organizations. Once the structure of an organization is established, it tends to persist over time despite environmental changes. Later researchers adopted Stinchcombe’s imprinting hypothesis to identify the effects of founders on the processes, practices, strategies, structures, and culture of the organizations that they found [32,33,34,35,36]. Thus, a founder may be viewed as an “imprinter”, whereas the organizations that he or she founds are regarded as being “imprinted”. For example, Baron, Burton, and Hannan [32] (p. 532) argue that “[a] founder’s blueprint likely ‘locks in’ the adoption of particular structures”.

An imprinting perspective provides us with a way of understanding how a social entrepreneur could influence the sustainability of competing institutional logics. First, social entrepreneurs are important actors who can determine how organizations respond to competing logics. These actors are analogous to “institutional agents” [37], “institutional entrepreneurs” [38], “institutional champions” [39], or “institutional actors” [40]. Kim et al. [37] (p. 289) explain that “[i]nstitutional agents are individuals or groups who invest their resources, [including], time, effort, and power in promoting a particular institutional logic along with organizational forms and practices that reflect that logic”.

Second, a social entrepreneur interprets the strategic narrative of his or her organization, which is how they may make sense out of what is occurring [41,42]. Research on issue interpretation has shown evidence that organizational responses to strategic challenges are dependent upon a decision maker’s strategic issue interpretation. The way decision makers evaluate a challenge can affect their strategy [43,44,45]. Therefore, it is worth considering how the extent to which differences in evaluation by a social entrepreneur could influence the sustainability of competing institutional logics.

Third, a social entrepreneur determines how resource are allocated, which impacts the strategic direction of an enterprise. For example, research has shown that a firm’s outcomes occur, not because of resource endowment differences, but because of different usages of endowed resources [46]. Hence, it is possible that sustainability could be affected by a social entrepreneur distributing resources within an organization.

3. Hypotheses Development

3.1. The Cuvilinear Relationship between Non-Profit Experience and the Sustainability

A founder’s previous work experience could impact the processes, structures, or strategies of newly founded organizations [47]. Prior to starting an organization, job experience is strongly associated with a founders’ creation of a vision [48], preference [34], identity [33], knowledge structure [49,50], and social capital [51]. We suspect that a social enterprise’s sustainability of commitments to competing logics depends in part on its founder’s non-profit experience, which we define as a founder’s time working in the non-profit area prior to starting a social enterprise. Although there is no single theory that can directly explain the relationship between non-profit experience and sustainability, there are several potential explanations why the non-profit experience of a social entrepreneur can positively impact sustainability of commitments to social logics and commercial logics.

First, because social entrepreneurship and the non-profit sector share similarities such as problem solving, non-profit experience allows social entrepreneurs to acquire industry specific knowledge for launching a social enterprise. In fact, a founder’s work experience in a similar industry would cultivate specific industry knowledge, which is positively related to organizational outcomes [52,53]. Many studies suggest that prior specific industry experience helps founders grasp consumer needs [54], identify more opportunities [55], and uncover more precise information [56]. Therefore, non-profit experience may increase the ability to identify social problems, gather information, and acquire resources for both logics, which may be positively related to high levels of sustainability of commitments to competing logics.

Second, individuals with non-profit experience could be at least partially trained to be social entrepreneurs who can lead an effort to achieve both a social and a commercial logic, perhaps as a result of the special features of non-profit working environments that can enhance diverse skills sets, social capital, and tolerance of uncertainty. Previous research suggests that non-profit organizations may allow greater autonomy and decision-making discretion [57]. Increased work autonomy could expose employees to a wider spectrum of information, more diverse contacts, and higher levels of uncertainty [58]. In fact, research indicates that non-profit experience may help to cope with ambiguity, which is positively associated with successful entrepreneurial outcomes [59]. Therefore, it is plausible that an experienced social entrepreneur will be able to manage competing logics better than those who do not have such an experience.

Finally, experience in the non-profit sector is more likely to legitimate founders as social entrepreneurs than experience in the for-profit sector. Legitimacy is important because otherwise an organization could be perceived as less desirable, proper, and appropriate [60]. Because a lack of legitimacy could make it difficult to attract supporters, resources and endorsements from communities, governments, or donors, scholars have emphasized the importance of attaining it [61]. Previous studies proposed that a key to social entrepreneurial legitimacy is alignment with the non-profit sector [8,62]. For example, Parkinson and Howorth [62] argue that social entrepreneurs perceive themselves to be legitimated more by their social morality than through traditional entrepreneurial activities. Conversely, a founder without non-profit experience may be perceived as having a legitimacy deficit, which could prevent his or her social enterprises from achieving a high level of sustainability. Thus, we propose that there is a positive relationship between a social entrepreneur’s non-profit work experience and sustainability of dual commitments to competing logics.

However, there may be a point above, as an increase in a founder’s non-profit experience does not add to a social enterprise’s capacity to sustain dual commitments. In other words, at higher levels of non-profit experience, added founder experience in the non-profit sector may impede achieving sustainability of dual commitments. In fact, it may even decline at high levels. We explore three explanations among many others to explain when (or why) a social entrepreneur’s non-profit experience could weaken the sustainability of dual commitments of competing logics based on (1) the constraints of knowledge structure, (2) prioritizing socialization, and (3) identity conflict.

First, an excessive amount of non-profit experience may restrict a founder’s knowledge of other sectors. In general, previous studies posit that experience above a certain point creates decision-making rigidities [63,64]. This is mainly because individual decision makers are rationally bounded and prefer to exploit their existing knowledge [65]. For example, Benner and Tripsas [66] demonstrate that prior experience shaped a firm’s belief structure. Similarly, Fern, Cardinal, and O’Neil [50] found that the strategic choices of new entrants were constrained by a founder’s past experience. They argued “founders who relied on their industry experiences may replicate strategies of legacy firms” (p. 427). The extant research, therefore, implicitly indicates that experienced social entrepreneur may fail to achieve sustainability of dual commitments because they simply replicate the structures, practices, or strategies of their previous non-profit organizations.

Second, founders with extensive non-profit experience may not only hire employees with a background in social work, but also it may socialize them to prioritize a social logic over a commercial logic, which could decrease the sustainability of dual commitments of competing logics. Previous studies have documented the importance of socialization practices that maintain the hybridity of social enterprises [6,15]. For example, Battilana and her colleague [15] argue that it is possible for socially imprinted founders to set up an organizational system for social wealth maximization, not economic profitability.

Third, founders who have largely spent their career within the non-profit sector may perceive their role more as “nonprofit workers” than “entrepreneurs”. Role identity refers to a person’s sense of self with regard to a specific role [67]. According to identity theory, expectations and meanings associated with a role, such as a doctor, teacher, parent, and worker may guide an individual’s behavior [68]. In addition, if one of the role identities has more salience, it could provide more meaning and invoke behaviors related to a salient role identity [69,70]. Because salience is affected by the amount of commitment [71], the idea of identity salience suggests that a long time spent in the non-profit sector can confer a stronger salience for a “nonprofit worker” identity than for an “entrepreneurial” identity, which helps experienced social entrepreneurs to be supportive of social logics, rather than commercial logics. There is similar evidence in the academic entrepreneurship literature, which indicates that tenured scientists who spent a long time being trained in academia are not likely to act as pure entrepreneurs, despite their commercialization experience [72].

Consistent with the above reasoning, we hypothesize that a social entrepreneur’s non-profit experience will exhibit a non-linear relationship with sustainability of dual commitments. Sustainability of dual commitments increases at a low-to-moderate rate, based on non-profit experience, but turns negative with a moderate-to-high rate for non-profit experience.

Hypothesis 1.

There is a curvilinear relationship between a founder’s level of non-profit experience and the sustainability of dual commitments of competing institutional logics.

3.2. The Moderating Role of a Social Entrepreneur’s Attributes

Scholars have argued that a firm’s strategic focus is heavily affected by a CEO’s cognitive structure [73]. Thus, it is unlikely that the hypothesized curvilinear relationship between non-profit experience and sustainability of dual commitments to competing logics is universal across different cognitive structures. Accordingly, we explore two attributes of social entrepreneurs, which are associated with cognitive structure: (1) ambivalent interpretation and (2) career variety. We expect these two variables to moderate the proposed curvilinear relationship.

3.2.1. Ambivalent Interpretation of a Social Entrepreneur

Since decision makers’ interpretation at the individual level shapes the action at organizational level [45,74], better understanding of achieving competing logics inside social enterprises requires the knowledge about how their decision makers interpret complex environments. According to research on strategic diagnosis, top managers interpret external environments as either positive or negative [75]. Organizational actions are depending on either positively or negatively interpreted issues. Recently, however, scholars have not only argued that decision makers frequently interpret the environment ambivalently, holding positive and negative evaluation simultaneously, but also show its effects on organizational actions. More specifically, if decision makers interpret issues ambivalently, both positively and negatively, organizations can invite wide participation, reduce potential conflicts, and increase the scope of actions [76]. They hint that a decision maker’s ambivalence could help an organization to coexist with different and competing objectives. Therefore, we expect that the curvilinear effects of non-profit experience on the sustainability of competing logics will be minimal in social enterprises with an entrepreneur who evaluates strategic issues ambivalently. This is likely to be reasonable for several reasons.

First, a social entrepreneur’s ambivalence is an organizational condition that may impact a resource-allocation decision. Much research argues that positive strategic issues are more likely to attract organizational resources than negative ones [77,78]. However, ambivalent individuals are less likely to evaluate an issue either as positive or negative, which implies that they are likely to evaluate social and commercial issues as both positive and negative. Furthermore, critical resources will be distributed similarly either to social activities or commercial activities if a social entrepreneur is ambivalent, even if he or she lacks non-profit experience or has spent too much time in the non-profit sector.

Second, a social entrepreneur’s ambivalence is associated with organizational ambidexterity [76], defined as the capacity to achieve trade-offs [79]. A social entrepreneur’s ambivalence can be related to broad-mindedness, which may be linked to a wider spectrum of issues [76] (pp. 693–694). This wider spectrum derived from ambivalence can be useful for dealing with complexity of competing logics. It might also make founders’ previous nonprofit experience irrelevant in terms of sustainability of dual commitments to competing logics.

Third, a social entrepreneur’s ambivalence is also associated with the perception that “important values lead to actions consistent with them” [80] (p. 1334). By valuing both a commercial and a social logic, ambivalent social entrepreneurs are less likely to respond more to one of them, although there is pressure to do so, due either to their limited or higher range of non-profit experience.

Thus, it is logical to assume that the positive benefits of low-to-moderate levels of a founder’s non-profit experience on sustainability of competing logics may become less salient with a high level of ambivalence. At a moderate-to-a-high level of founder non-profit experience, diminished returns to sustainability will be mitigated as a social entrepreneur’s ambivalence increases. We hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2.

A social entrepreneur’s ambivalence will moderate the curvilinear relationship between his or her non-profit experience and sustainability of dual commitments to competing logics; specifically, the curvilinear relationship will be less pronounced (i.e., exhibit less curvature) among social enterprises with their founder exhibiting a higher level of ambivalence than ones with a founder exhibiting a lower level of ambivalence.

3.2.2. Career Variety of a Social Entrepreneur

A social entrepreneur’s career variety is similar to a traditional CEO’s career variety, which refers to “the array of distinct professional and institutional experiences an executive has had prior to becoming a CEO” [81]. We also expect that an organization with a social entrepreneur who has high career variety will attenuate the impact of non-profit experience on sustainability of competing logics. The reasons are threefold.

First, one of the features of CEO career variety is an awareness of many paradigms and exemplars [81]. High-variety CEOs seem to possess cognitive breadth, defined as an awareness of multiple perspectives, which makes it possible to view problems from different perspectives. It ultimately helps them to generate creative solutions [81]. Knowledge of multiple perspectives implies that a high-variety social entrepreneur may better understand a venture’s circumstances, the so-called “utility function” of customers, funders, and other important resource providers, than a low-variety social entrepreneur [82]. These benefits from career variety may help social entrepreneurs understand what consumers want, how to approach the market, or how to gain legitimacy, despite having less non-profit experience. Social entrepreneurs with various career paths may be able to manage a higher level of achievement of dual commitments to competing logics without the help of prior non-profit experience. Conversely, these benefits also help to mitigate the negative relationship with sustainability at a moderate-to-high level of non-profit experience as career variety increases, because open mindedness from it may also help them overcome their constrained knowledge structure, restricted hiring processes, and “social mission oriented identity” generated from extensive time spent in the non-profit sector.

Second, CEO-career variety is also associated with social capital, which consists of resources derived from someone’s social relations [83]. Social capital shapes the conditions that convey knowledge and resources in an organization by connecting to both inside and outside groups [84,85]. Social capital generated by career variety may provide the capability not only to understand diverse opinions [48,86], but also to control the allocation of knowledge and resources [84]. These capabilities may be critical drivers for achieving dual commitments to competing logics even without non-profit experience.

Third, a CEO’s career experiences may be associated with human capital. Human capital refers to acquired knowledge and skills via investments in schooling, on-the-job training, and work-related experience [87]. Research has generally supported a positive relationship with effective and efficient venture management [88]. Various experiences may provide a CEO with effective management skills for different value environments.

Even if social entrepreneurs lack non-profit experience, having various career paths, they may be able to sustain dual commitments to competing logics using their accumulated social and human capital. Conversely, at moderate-to-high levels of non-profit experience, the negative relationship with sustainability will be attenuated if social entrepreneurs have a high level of career variety. Together, these arguments suggest that a curvilinear relationship between the non-profit experience of a social entrepreneur and sustainability of dual commitments to competing logics will be weaker for social entrepreneurs with a high degree of career variety.

Hypothesis 3.

Career variety will moderate the curvilinear relationship between non-profit experience and sustainability; specifically, the curvilinear relationship will be less pronounced (i.e., exhibit less curvature) for social enterprises when their founder has higher career variety.

4. Methods

4.1. Sample and Data Collection

The sampling frame is Korean social enterprises. There are several reasons why this population is appropriate for hypothesis testing. First, it overcomes the problem of identifying acceptable social entrepreneurial organizations. Previous researchers have relied on self-identified organizations [89], which introduces potential bias. Clearly, it is challenging to conduct large-sample, empirical research while avoiding bias [90]. Fortunately, South Korea has developed a useful classification scheme. Organizations that fail to satisfy the criteria are not allowed to call themselves social enterprises [91,92], which since 2007 has been mandated under Section 19 of the Social Enterprise Promotion Act.

Second, South Korea is a society in which social and commercial logics are fiercely separated. For example, management philosophy in South Korea has been influenced by U.S. firms [93], whereas its welfare system follows the “Nordic” or “social-democratic” welfare regime of European countries [94,95,96]. Thus, South Korean social enterprises provide a clearer view of their social and commercial logics than most countries.

We collected the data for this study from a survey of Korean social enterprises using the Korea Social Enterprise Promotion Agency’s directory, which tracked 1012 certified social enterprises from 2013 to 2014. Following the total design method suggested by Dillman [97], we conducted 11 preliminary interviews with social entrepreneurs between April and July 2013. We selected the organizations to understand how they would respond to competing institutional logics, as well as to refine the questionnaire’s items (see Appendix A for a brief description of the 11 social enterprises). After considering the feedback, we prepared the final questionnaire. We created it in English first, later translating it into Korean, consistent with the suggestion of Brislin’s [98] translation–back-translation approach.

We sent an email containing the final questionnaires to 1002 eligible social enterprises over a period of four months from April to July of 2014. The email explained the goal of the study, the voluntary nature of participation, its confidentiality policy, and a link to the survey’s Web site. The letter promised that an executive summary of the results would be provided as an incentive to each participant. After sending an invitation, we emailed three reminders and made several phone calls [99]. These efforts generated 281 responses from CEOs, representing a response rate of 28.04%, which compares favorably with other managerial surveys [100].

In order to avoid common method bias and social desirability bias, defined as the tendency that respondents are likely to report overtly “good behavior” and rarely “bad behavior”, we used third-party observers as CEO informants. We contacted the 281 social enterprises again and asked middle managers the extent to which relevant topics were discussed [101]. In total, 203 social enterprises completed two sets of surveys. We deleted 13 responding firms due to missing data, resulting in a total of 190 usable responses (for a total usable response rate of 18.96%).

To assess representativeness, we tested for non-response bias in three different ways. First, as seen in Table I, we contacted 30 non-respondents randomly by telephone and asked them to provide demographic information about their company [102]. Then, we compared group mean differences between respondents and 30 non-respondents on background characteristics such as firm age, firm size, number of board of directors, and a firm’s 2012 debt ratio. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) of group means revealed no significant differences (see the Table 1; Fs < 0.10, p > 0.10).

Table 1.

Test of non-response bias: comparison with non-respondents.

Second, to assess non-response bias [103], we compared early respondents with late respondents on key theoretical constructs as well as several control variables. On average, 38.5% of the sample responded to the early mailing, whereas 61.5% of the sample were late responders. The results of the t-tests indicated no significant differences between early and late respondents (p > 0.10). Finally, we compared the firms in the samples to 1002 firms in the initial mailing list with respect to their types. KSEPA classified five different types of social enterprises: (1) social service, (2) work integration social enterprises (WISEs), (3) a mixture of social service and WISEs, (4) community-based, and (5) others. A Komogorov–Smirnov (KS) two-sample test identified no significant differences between the two groups. (χ2 = 8.114, p = 0.09 > 0.05). Using these three tests, we determined that nonresponse bias was not a problem.

4.2. Dependent Variable

In order to assess the sustainability of dual commitments to competing logics as the dependent variable, we operationalized top management’s commitments to strategic issues both social and commercial as proxies of commitments to competing logics [104]. Adopting the items used by prior research [105,106] and considering feedback from 11 social entrepreneurs who we interviewed, we listed a broad range of topics that could be discussed by top managers [105]. Then, we asked the respondents to rate “the extent to which various subjects were topics of conversation for their firm’s top management team” [105] (p. 549). To be specific, middle managers assessed how often top managers discussed (1) seeking the good of society, (2) the company’s role in society, (3) improving social conditions, (4) efforts for beneficiaries, (5) financial performance, (6) stockholders and investors, (7) strategy and planning, and (8) productivity and efficiency. We asked middle managers to complete a randomly ordered eight-item list of questions on a seven-point Likert-style scale (1 = never, 7 = very frequently). The first four indicators pertained to top management’s social issues and the second four items pertained to commercial issues.

To evaluate reliability and validity, we calculated Cronbach’s alpha for each of the four items, which yielded an acceptable Cronbach alpha = 0.90 for attention to social issues and 0.75 for commercial issues. Then, we used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to examine the validity of the measures. Although the result showed an acceptable model fit (χ2 (18) = 37.58; χ2/df = 2.08; CFI = 0.976; TLI = 0.962; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.075), the standardized factor loading of the sixth item was below the recommended threshold of 0.05 [107]. After dropping it, Cronbach’s alpha was increased from 0.75 to 0.83 for top management’s attention to commercial issues. The modified result of CFA also achieved better fit (χ2 (12) = 26.46; χ2/df = 2.20; CFI = 0.982; TLI = 0.968; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.078). All factor loadings were also higher than the cutoff point (range from 0.75 to 0.90) and significant (p < 0.001). We obtained AVE values of 0.67 for top management’s attention to social issues, and 0.62 for commercial issues were obtained in this study, which indicated acceptable discriminant validity [108]. Consequently, we computed top management’s attention to social issues as the average of the four items, whereas the construct of top management’s attention to commercial issues was a mean of three items. See Table 2.

Table 2.

Validity assessment for constructs of top management’s commitments to issues.

To capture sustainability of dual commitments to competing logics, we used the Janis–Fadner (JF) coefficient of imbalance, which has been used to calculate media tenor [109,110] and work–family balance [111]. This coefficient allows us to measure the relative proportion of top management’s commitment to social issues and commercial issues. The formula is:

where S represents top management’s commitment to social issues, C is the commitment to commercial issues, and T is the total commitment. The range of this variable is −1 to 1, where 1 equals “commit to all social issues” and −1 equals “commit to all commercial issues”. To interpret them, a score of zero represents equal weighting for top management’s commitment to both competing issues, which further indicates a high level for sustainability of dual commitments to competing institutional logics. On the other hand, positive scores represent a social welfare logic focus, and negative scores represent a commercial logic focus. We converted the negative scores to absolute values; then, we used the reversed absolute number of the score by multiplying it by a constant −100 so that a greater value indicates a higher level of sustainability of dual commitments to competing logics. Maximum is 0.00, minimum is −35.35.

4.3. Explanatory Variable

4.3.1. A Social Entrepreneur’s Non-Profit Experience

Following previous research [112,113], a social entrepreneur’s non-profit experience can be measured by the number of years he or she reported having worked in the non-profit sector prior to starting the current social enterprise. Respondents were asked to answer the question: “how long have you had experience in non-profit sectors prior to your current social enterprise”. The average years of experience were 5.89 years.

4.3.2. Ambivalent Interpretation

We asked social entrepreneurs to indicate their positive or negative evaluation of a recent trend through the use of a vignette. This approach is similar to prior research on the evaluation of strategic issues [45,76]. It described the current direction of government policy toward social entrepreneurship, from direct financial support to indirect market-oriented policy (see Appendix B for more detail). The current shift of policy in the vignette has both positive and negative aspects for social enterprises. We expect that market-based policy, such as an increase in the number of sales channels, will provide social enterprises with an opportunity to scale-up; however, social enterprises will be confronted with market-based competition because of the reduction in subsidies provided by the government, which leads to the prioritization of a commercial logic over a social-welfare logic. We measured both the positive and the negative evaluations using a seven-point Likert scale each (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). See Table 3.

Table 3.

Validity assessment for constructs of ambivalent interpretation.

We computed ambivalent interpretation using a similarity-intensity model (SIM), which was employed by Thompson, Zanna, and Griffin [114]. Ambivalence increases when the similarity between positive and negative is increased as well as when there is greater intensity for both positive and negative outcomes [115]. The formula follows: A = (D + C)/2 − (D − C), where D is the dominant reaction and C is the conflicting reaction. For example, if a respondent’s evaluation of a recent trend receives a “6” for the rating of “positive” and a “4” for the rating of “negative”, then D = 6 and C = 4. Ambivalence can be calculated by (6 + 4)/2 − (6 − 4), which equals 3. Although there are “4” for “positive” and “6” for “negative,” D, C, and the ambivalence score are identical to the former case. On the other hand, if both positive and negative evaluations are “7”, the ambivalence score becomes “7.” The greater the presence of both positive and negative evaluations at the same time, the higher the overall ambivalence score [76,114].

4.3.3. Career Variety

We measured career variety using seven items: (1) the number of industries, (2) the number of organizations, (3) the number of functions in which an entrepreneur had worked prior to becoming a social entrepreneur in the focal firm, (4) age, (5) the total years of career experience, and (6) the education level [81]. We conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to assess convergent and discriminant validity as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Social entrepreneur’s career variety: exploratory factor analysis.

The results in Table 4 are consistent with previous studies. Therefore, we computed the final measure of career variety by summing the number of industries, organizations, and functional areas, divided by a social entrepreneur’s total years of career experience. The average value was 1.66, ranging from 0.15 to 15. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.76.

4.3.4. Control Variables

Because many other factors could systematically affect the pressure to respond to either a social logic or a commercial logic, we included numerous variables in the analysis for the purpose of control. For example, we measured prior performance by eight items with a seven-point Likert scale. Industry was measured by seven dummy variables. Appendix C details the control variables used in this study.

4.4. Analysis

In order to test the possible curvilinear relationship between a founder’s non-profit experience and sustainability, as well as the proposed moderating effects of a social entrepreneur’s ambivalence and career variety, which are H1, H2, and H3, we used moderated hierarchical regression. Management scholars have used this approach to detect curvilinear moderation [116,117]. We mean-centered the variables before we squared the independent variable, founder’s non-profit experience, and created the interaction terms in order to minimize any multicollinearity [118]. All VIF’s were below 3 so that multicollinearity was not an issue.

5. Results

Table 5 reports the results of the hierarchical regression model predicting sustainability of dual commitments to competing logics.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics and correlation.

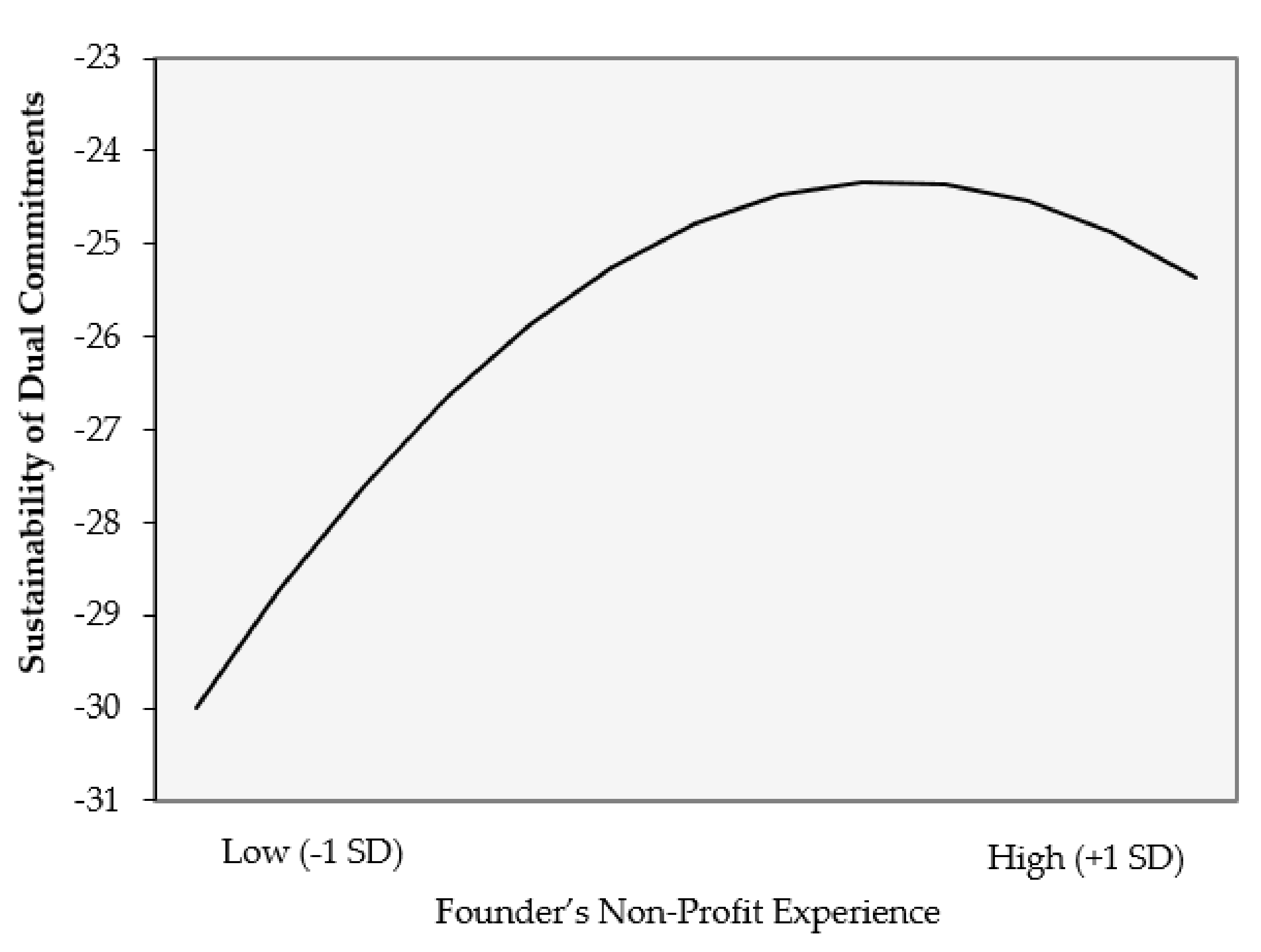

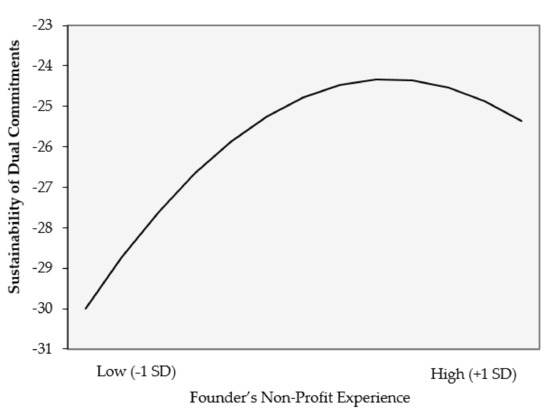

Table 6 reports the results of the hierarchical regression model predicting sustainability of dual commitments to competing logics. Only control variables are incorporated in Model 1 in Table 6. In order to test a non-linear relationship as proposed in H1, we entered into Model 2 the linear and squared term of founder’s non-profit experience (number of years and number of years2 in non-profit sectors). To support the hypothesized curvilinear relationship, the coefficient for the squared term would be positively significant for sustainability of dual commitments. As shown in Model 2 in Table 6, there is a positive coefficient for the linear term for a founder’s non-profit experience (β = 0.268, p = 0.031 < 0.05) and a negative coefficient for the squared founder’s non-profit experience term (β = −0.343, p = 0.006 < 0.01). Both terms were significant for sustainability of dual commitments. R2 for Model 2 is 0.242, which means 24.2% of the variance in sustainability of dual commitments to competing logics was predicted by a founder’s non-profit experience. In addition, a significant change in R2 from Model 1 supports the improvement of the model (∆R2 = 0.036, p < 0.05). This result provides evidence of a curvilinear relationship between a founder’s non-profit experience and sustainability of dual commitments, as proposed in H 1. Thus, Hypothesis 1 received support.

Table 6.

Results of hierarchical regression model.

Next, we expected that the curvilinear effects of a founder’s non-profit experience on sustainability of dual commitments to competing logics would depend on a social entrepreneur’s ambivalence and career variety. Thus, model 3 in Table 7 adds ambivalence and career variety as moderators.

Table 7.

Results of hierarchical regression model for moderating effects.

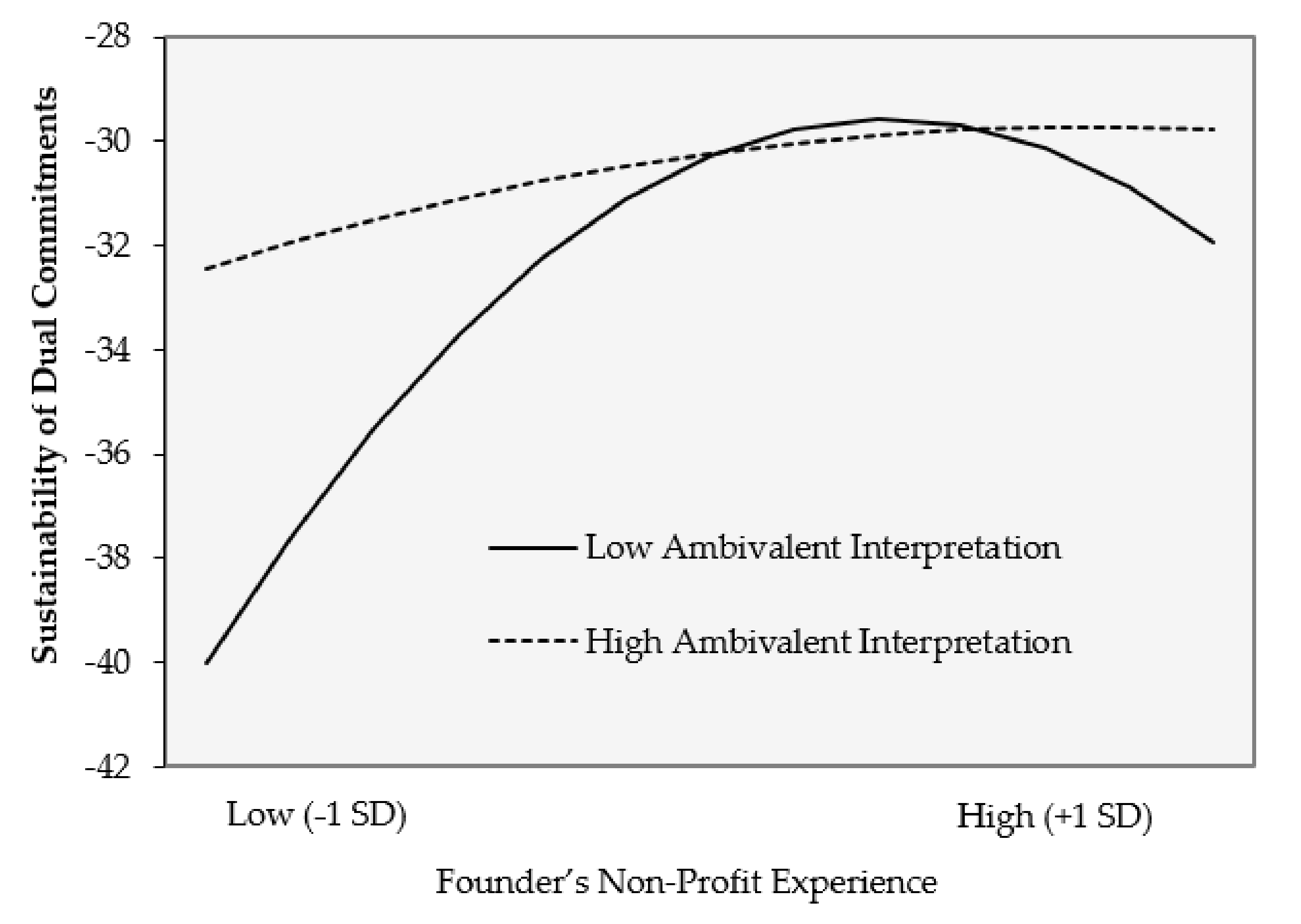

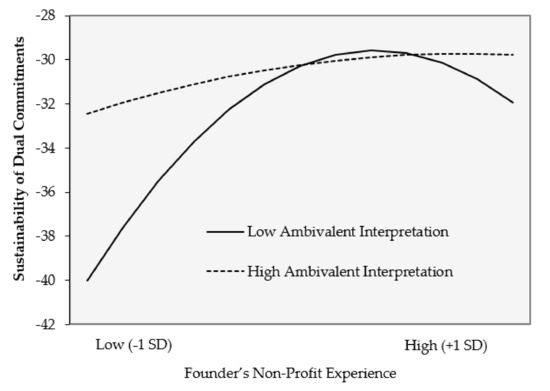

Following previous research [119], we added linear and quadratic-by-linear interactions for a founder’s non-profit experience and an ambivalent interpretation, as indicated in Model 4 in Table 7, and as specified in Hypothesis 2. F-tests on the changes in R2 indicate that the inclusion of the interaction terms leads to a better model for sustainability of dual commitments (∆R2 = 0.025, p < 0.01). The interaction term of an ambivalent interpretation × a founder’s non-profit experience2 is positive and significant (β = 0.344, p = 0.032 < 0.05), indicating that a founder’s ambivalence strengthens the positive effects of low-to moderate levels of a founder’s non-profit experience, while reducing the negative effects of moderate-to-high levels of a founder’s non-profit experience on sustainability of dual commitments. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

Finally, we entered the linear and quadratic-by-linear interactions of a founder’s non-profit experience and career variety in Model 5 in Table 7. Hypothesis 3 predicted that the curvilinear relationship between a founder’s non-profit experience and sustainability of dual commitments would be less with high career variety. Although the direction of the effect would be in the hypothesized path, there was no significant evidence for supporting H3 (β = 0.199, p = 0.161 > 0.10).

We plotted the curvilinear relationship between a founder’s non-profit experience and the sustainability in Figure 1. Then, in order to demonstrate how ambivalent interpretation moderates the focal curvilinear relationship, Figure 2 shows that the curvilinear relationship between founders’ non-profit experience and sustainability of dual commitments in their social enterprises is less profound for those with high, as opposed to low, ambivalence.

Figure 1.

Impact of founder’s non-profit experience on sustainability of dual commitments to competing logics.

Figure 2.

Impact of founder’s non-profit experience on sustainability of dual commitments to competing logics at different ambivalent interpretations.

6. Robustness Check

To check the robustness of the findings, we conducted two additional analyses. First, the current level of sustainability of dual commitments can be heavily influenced by the previous level. We controlled for prior sustainability of dual commitments by incorporating labeling claims, defined as an organization’s self-categorization either to a social or a commercial orientation. Scholars have argued that labels or vocabularies are key building blocks to offer important signals about organizations’ value and expectation [120,121]. Thus, institutional logics reflect different vocabularies or categorization, which influences how stakeholders perceive [122,123,124]. Therefore, we asked middle managers to indicate the extent to which their organization employed either a social organization or commercial company label in the organization’s name prior to starting the business.

Both labels can be separately assessed using a one-item and seven-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). We calculated their prior sustainability of dual commitments by using the Janis–Fadner [125] coefficient,

where S is the social enterprise label, C is the commercial enterprise label, and L is the total labeling. Larger absolute scores represent a lower level of sustainability of dual commitments. Similarly, we reversed the absolute score of the coefficient by multiplying it by a constant −100 so that a greater value indicates a higher level of the prior sustainability of dual commitments to competing logics. Despite the inclusion of the prior sustainability of dual commitments, the significance levels of effects have remained essentially the same in Table 8.

Table 8.

Robustness check: adding prior sustainability of dual commitments.

Second, we conducted regressions with a founder’s for-profit experience as an alternative independent variable. This is quite important because recent research suggests that a founder’s for-profit experience also has a non-linear effect on the hybridity of a social enterprise [30]. Therefore, we replaced a founder’s non-profit experience with for-profit experience. Then, we re-ran the regressions from Model 9 to Model 12 in Table 9. However, we did not find a significant relationship between founder’s for-profit experience and sustainability of dual commitments.

Table 9.

Robustness check: change of IV.

7. Discussion

This research tested what influences variations in a social enterprise’s incorporation or prioritization of competing logics. Drawing on the imprinting perspective [35], we hypothesized that the variation of achieving both a social logic and a commercial logic is associated with its founder of a social enterprise. We identified a social entrepreneur’s specific attributes as either antecedents or moderators. Specifically, we investigated the possibility of a curvilinear relationship between his or her non-profit experience and the sustainability of dual commitments to competing institutional logics (H1). We also hypothesized that a founder’s ambivalent interpretation (H2) and career variety (H3) would play a moderating role in the proposed curvilinear relationship. Our empirical findings demonstrated that a social entrepreneur’s non-profit experience has a positive influence on the sustainability of competing logics until reaching a certain point, beyond which that relationship is likely to be negative. Moreover, we found that the effect of a social entrepreneur’s non-profit experience on the sustainability of competing logics is less profound in enterprises with a highly ambivalent founder. However, we did not find support for the moderating effect of career variety on social entrepreneurs. Initially, we predicted that a social entrepreneur’s non-profit experience on the sustainability would be less profound in social enterprises with a founder who has followed various career paths; however, the data suggests that career variety—various professional and institutional experiences—is a relatively unimportant condition as a moderating mechanism.

7.1. Theoretical Implication

This research contributes to the literature as follows: First, our work extends current literature on social entrepreneurship by seeking out the factors that enable social enterprises to simultaneously commit to competing institutional logics over time. Scholars have recognized that social enterprises benefit from incorporating competing institutional logics in a sustainable way [126,127,128]; however, in the real world, many social enterprises prioritize either a social welfare logic or a commercial logic [129,130,131,132,133]. Nonetheless, previous research has not explored the condition under which some social enterprises successfully sustain commitments to competing logics without prioritization of one over another, while others pay much more attention to either a commercial logic or a social welfare logic separately [134,135,136].

Second, we drew on the imprinting perspective to build a linkage between a social entrepreneur’s life experience and the sustainability of dual commitments to competing logics. An imprinting perspective suggests an individual’s life experience serves as a “cognitive filter” that shapes his or her values or perceptions of the environment, which significantly impacts on her subsequent strategic decision making [137,138]. In recent years, the careers of top managers have attracted the attention of scholars in the nonprofit sector as well as in social entrepreneurship [139,140,141]. Thus, we identified a founder’s non-profit experience as a significant imprinter on sustaining dual commitments to competing logics inside social enterprises. Interestingly, the relationship between the years of a founder’s non-profit work experience and the sustainability of competing institutional logics is a curvilinear, inverted U-shape. This result is consistent with prior research on the benefits of non-profit career [142,143]; however, we extend extant literature by showing non-linear effects of traditional non-profit experience on sustainability of competing logics. Moreover, this relationship is also contingent upon a social entrepreneur’s ambivalent interpretation. In other words, the curvilinear effects of a social entrepreneur’s non-profit experience are less profound in social enterprises when an entrepreneur’s interpretation is ambivalent.

Third, we operationalize and test the sustainability of competing logics in a social entrepreneurship context. Recent research has called for easily assessed measures for social entrepreneurship’s specific variables. For example, Short et al. [90] suggest that there are opportunities to advance the social entrepreneurship literature by providing relevant measures. The proposed operationalization of the sustainability of competing logics allows us to access and administer the data collection in a way that reduces its complexity.

Finally, we provide empirical evidence by collecting and analyzing large-scale data. Although social entrepreneurship has received much scholarly attention, it has been criticized, because relatively few studies have used quantitative data for hypothesis testing, and more empirical studies have been called for [90,144]. Additionally, empirical research has been focusing more on the non-profit context, whereas the for-profit context has not been studied extensively. In this study, we theorized and tested a number of hypotheses with both non-for-profit and for-profit social enterprises.

7.2. Practical Implications

There are several practical implications. First, knowing that a founder’s non-profit experience is the key instrument for maintaining both a social welfare logic and a commercial logic at comparably high levels allows institutions, government, or investors supporting social enterprises to estimate their capacity to increase hybridity [1]. More specifically, our results help them avoid risking the prioritization of competing institutional logics by showing the extent which social entrepreneur’s non-profit experience impacts on the sustainability of dual commitments to competing logics.

Second, our findings suggest that individuals who desire to be a social entrepreneur would be better if they spend a decent amount of time in the nonprofit sector before they start their social enterprises. However, it is noted that excessive time spent in the nonprofit sector is likely to reach a point of diminishing returns. Our empirical result indicates that the sustainability of competing logics reaches its apex before 10 years of career experience in the nonprofit sector. After that, it decreases. Aspiring social entrepreneurs should be aware that too much work experience in the non-profit sector can limit one’s ability to incorporate both a social mission and a commercial mission. Hence, being neither too social nor too commercial requires spending appropriate amounts of time in non-profit sectors.

Third, we suggest that the effective use of a social and a commercial logic requires social entrepreneurs to be trained as “ambivalent CEOs”. Our results show that if founders can evaluate dilemmas positively and negatively at the same time, their social enterprises are more likely to achieve sustainability, regardless of their prior non-profit experience. This finding is consistent with previous research, which argued that social entrepreneurs should be taught to shape their mental models from distinctive to paradoxical thinking [145]. Therefore, cultivating the ability of social entrepreneurs to perform ambivalent interpretation is strongly recommended so that they can effectively manage the achievement of both a social and a commercial mission.

7.3. Limitations and Future Research

Although this study has advanced our knowledge of some aspects of social entrepreneurship, it is not without limitations, which raises possibilities for future research. First, because of the extreme difficulty of collecting objective data in the field of social entrepreneurship, the data in this study basically consist of “self-reported” disclosures, which can be potentially associated with recall bias and social desirability bias. However, we argue that these concerns are minimal, because several remedies already have been applied. For example, following the suggestions of previous researchers [146], respondents were asked to go back in time and remind themselves of facts, not just their opinions at the time. In addition, similar to previous research, we informed the respondents that the data would be aggregated, reviewed only by the authors, and used strictly for research. In order to avoid social desirability bias, we also used multiple informants [101]. After collecting independent variables and control variables, we contacted middle managers to acquire dependent variable data. Nonetheless, the study suggests that future research can benefit from more objective data sources, or different approaches such as natural experiments or simulation methods.

Second, in terms of the generalizability of our results, it is possible that the results of this research were influenced by the specific situation of government-driven policy in the Korean context. Although using accredited Korean social enterprises makes it possible to conduct large-scale empirical analysis, it would also be advisable to compare the obtained results to similar studies conducted in other countries. By replicating the proposed models in other countries, future research may enhance the generalizability of these results and find other, more useful roles for public institutions.

Third, we treated the sustainability of competing logics as only a dependent variable, which was appropriate because we were studying its antecedents. We do not make any claims that achieving a high level of sustainability of competing logics is superior because it can be a source of internal conflicts. Clearly, though, sustainability can also be used as an independent variable for other important dependent variables such as social impact, social or commercial performance, internal conflicts, and innovation. In some cases, scholars can use the sustainability of competing logics as a moderator or a mediator.

Fourth, in our view, future research can benefit from identifying other important contingent factors for the relationships proposed in this study. For example, extant research suggests that a top manager’s own preference should be examined carefully. Building on agency theory and optimal contracting theory, Masulis and Reza [147] showed that there is a positive relationship between corporate charitable giving and a CEO’s charitable preferences. Therefore, future research could investigate whether a social entrepreneur’s preference could moderate the relationship between their non-profit experience and the sustainability of competing logics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.J.B. and J.O.F.; methodology, T.J.B.; formal analysis, T.J.B.; data curation, T.J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, T.J.B.; writing—review and editing, T.J.B. and J.O.F.; supervision, J.O.F.; project administration, T.J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Louisville.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to privacy issues.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the guest editors and anonymous reviewers.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Description of Interviewed Social Enterprises

Table A1.

Description of interviewed social enterprises.

Table A1.

Description of interviewed social enterprises.

| Case | Description of Interviewed Social Enterprises |

|---|---|

| 1 | A social venture (not accredited by Korean government) providing the new and more sustainable ad-system for internet-based companies |

| 2 | An accredited social enterprise, a catering services hiring disabled people |

| 3 | An accredited social enterprise, a cleansing service firm employing socially disadvantageous people |

| 4 | A social venture start-up, preparing the full launching the online/mobile gaming company. It provides the games to donate to charity |

| 5 | An accredited social enterprise, making a mobile app for donating to charity |

| 6 | An accredited social enterprise, developing and providing healing and recovery programs for community |

| 7 | A social venture (not accredited by Korean government, but supported by capital city) offering web-based service for social dining networks |

| 8 | An accredited social enterprise, a fair tourism company, which connects travelers with local communities as well as provides more sustainable ways of tourism |

| 9 | A social venture (not accredited by Korean government) serving a platform business with companies for fair tourism |

| 10 | An accredited social enterprise, a social work services in nursing homes |

| 11 | An accredited social enterprise, a maintenance, repair, and operating (MRO) supply service. It recruits and supports social enterprises as potential suppliers of MRO to big commercial companies |

Appendix B. Ambivalent Evaluation of Strategic Issues-Case

The Korean government decided to change its policy on social entrepreneurship from direct support to indirect guidance. For example, it has provided financial support to all accredited social enterprises for their first three years. However, from this point forward, it now will try to enhance market-oriented methods such as linking sales channels, increasing government purchasing, and developing capital market for social entrepreneurship.

To what extent do you agree with the following statements?

Positive interpretation (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree)

Our company will benefit from the current trend described above.

The current trend described above comprises a potential gain for our company.

Negative interpretation (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree)

The current trend described above is something negative for our company.

There is a high probability of losing a great deal because of the current trend described above.

Appendix C. Control Variables

Table A2.

Control variables.

Table A2.

Control variables.

| Variable Name | Variable Definition/Operationalization |

|---|---|

| Total commitments to issues | The sum of top management’s commitments both to social issues and commercial issues |

| Prior Performance | Measured by eight items, a seven-point Likert scale |

| Attainment Discrepancy | Dichotomous variable of “1” for positive score of (current performance expectation—past performance), and “0” otherwise |

| Firm Age | Measured by subtracting the date of founding from 2014 |

| Ratio of Debt | Measured by firm’s long-term debt divided by total assets (Barnett & Salomon, 2012) |

| Industry | Seven dummy variables to control for eight industrial categories: (1) Arts and Culture, (2) Civil and Human Rights, (3) Economic Development, (4) Education, (5) Environment, (6) Health/Healthcare, (7) Public Service, and (8) others |

| Type | Four dummy variables to control for five types of activities: (1) Social Service, (2) Work Integration Social Enterprises (WISEs), (3) Mixture of social service and WISEs, (4) Community-based, and (5) Others. |

| Diversity of Board of Directors | , where P is the proportion of board of directors with a past experience category i, N is the total number of experience categories. In this study, I identified four categories of past experience: (1) social sector, (2) commercial sector, (3) both social and commercial sectors, and (4) non-experience. |

| CEO duality | Dichotomous variable of “1” if CEO is the chairperson of the board, and “0” otherwise |

| Founder Age | Measured by the logarithm of the age |

| Founder Gender | Dummy coded “1” if founder is male, and “0” if not |

| Founder Education Level | Measured by 1 = high school, 2 = Bachelor’s degree, 3 = Master’s degree, and 4 = doctoral degree. |

| Founder’s for-profit experience | The number of years the social entrepreneurs reported having worked in the for-profit sector prior to starting the current social enterprise |

References

- Battilana, J.; Lee, M. Advancing Research on Hybrid Organizing–Insights from the Study of Social Enterprises. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2014, 8, 397–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, N.; Walker, J.; Bacq, S.; Kickul, J. Hybrid Organizations: Origins, Strategies, Impacts, and Implications. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2015, 57, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassmannshausen, S.P.; Volkmann, C. The Scientometrics of Social Entrepreneurship and Its Establishment as an Academic Field. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2018, 56, 251–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutter, C.; Bruton, G.D.; Chen, J. Entrepreneurship as a Solution to Extreme Poverty: A Review and Future Research Directions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P.H. Markets from Culture: Institutional Logics and Organizational Decisions in Higher Education Publishing; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Battilana, J.; Dorado, S. Building Sustainable Hybrid Organizations: The Case of Commercial Microfinance Organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 1419–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, J. Navigating Paradox as a Mechanism of Change and Innovation in Hybrid Organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pache, A.-C.; Santos, F. Inside the Hybrid Organization: Selective Coupling as a Response to Competing Institutional Logics. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 972–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pache, A.-C.; Thornton, P.H. Hybridity and Institutional Logics. In Organizational Hybridity: Perspectives, Processes, Promises; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vickers, I.; Lyon, F.; Sepulveda, L.; McMullin, C. Public Service Innovation and Multiple Institutional Logics: The Case of Hybrid Social Enterprise Providers of Health and Wellbeing. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 1755–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lattemann, C. Institutional Logics and Social Enterprises: Entry Mode Choices of Foreign Hospitals in China. J. World Bus. 2018, 55, 100974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.; Stevenson, H.; Wei-Skillern, J. Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: Same, Different, or Both? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Battilana, J.; Cardenas, J. Organizing for Society: A Typology of Social Entrepreneuring Models. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Gonin, M.; Besharov, M.L. Managing Social-Business Tensions: A Review and Research Agenda for Social Enterprise. Bus. Ethics Q. 2013, 23, 407–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J.; Sengul, M.; Pache, A.-C.; Model, J. Harnessing Productive Tensions in Hybrid Organizations: The Case of Work Integration Social Enterprises. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 1658–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laasch, O. Beyond the Purely Commercial Business Model: Organizational Value Logics and the Heterogeneity of Sustainability Business Models. Long Range Plan. 2018, 51, 158–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Besharov, M.L. Bowing before Dual Gods: How Structured Flexibility Sustains Organizational Hybridity. Adm. Sci. Q. 2019, 64, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, P.; Powell, W.W. From Smoke and Mirrors to Walking the Talk: Decoupling in the Contemporary World. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2012, 6, 483–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraatz, M.S.; Block, E.S. Organizational Implications of Institutional Pluralism. Sage Handb. Organ. Inst. 2008, 840, 243–275. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, J.G.; Lueg, R.; van Liempd, D. Managing Multiple Logics: The Role of Performance Measurement Systems in Social Enterprises. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.; Schneider, S.; Spieth, P. How to Stay on the Road? A Business Model Perspective on Mission Drift in Social Purpose Organizations. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 658–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, U.; Drencheva, A. The Person in Social Entrepreneurship: A Systematic Review of Research on the Social Entrepreneurial Personality. In The Wiley Handbook of Entrepreneurship; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 205–229. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkinson, G.P.; Healey, M.P. Cognition in Organizations. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 59, 387–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, R.; Hawn, O.; Ioannou, I. Willing and Able: A General Model of Organizational Responses to Normative Pressures. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2019, 44, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, E.S.; Sears, G.J. Walking the Talk on Diversity: CEO Beliefs, Moral Values, and the Implementation of Workplace Diversity Practices. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 164, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Preuss, L.; Pinkse, J.; Figge, F. Cognitive Frames in Corporate Sustainability: Managerial Sensemaking with Paradoxical and Business Case Frames. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2014, 39, 463–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żur, A. Entrepreneurial Identity and Social-Business Tensions—The Experience of Social Entrepreneurs. J. Soc. Entrep. 2020, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, S.; Lee, M.; Ramarajan, L.; Battilana, J. Blurring the Boundaries: The Interplay of Gender and Local Communities in the Commercialization of Social Ventures. Organ. Sci. 2017, 28, 819–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wry, T.; York, J.G. An Identity-Based Approach to Social Enterprise. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2017, 42, 437–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Battilana, J. How the Zebra Got Its Stripes: Imprinting of Individuals and Hybrid Social Ventures. In Harvard Business School Organizational Behavior Unit Working Paper; Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; No. 14–005. [Google Scholar]

- Stinchcombe, A.L. Organizations and Social Structure. Handb. Organ. 1965, 44, 142–193. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, J. Engineering Bureaucracy: The Genesis of Formal Policies, Positions, and Structures in High-Technology Firms. J. Law Econ. Organ. 1999, 15, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimberly, J.R. Issues in the Creation of Organizations: Initiation, Innovation, and Institutionalization. Acad. Manag. J. 1979, 22, 437–457. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, D.J. Organizational Genealogies and the Persistence of Gender Inequality: The Case of Silicon Valley Law Firms. Adm. Sci. Q. 2005, 50, 440–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Tilcsik, A. Imprinting: Toward a Multilevel Theory. Annals 2013, 7, 195–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, Z.; Fox, B.C.; Heavey, C. “What’s Past Is Prologue”: A Framework, Review, and Future Directions for Organizational Research on Imprinting. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 288–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-Y.; Shin, D.; Oh, H.; Jeong, Y.-C. Inside the Iron Cage: Organizational Political Dynamics and Institutional Changes in Presidential Selection Systems in Korean Universities, 1985–2002. Adm. Sci. Q. 2007, 52, 286–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P. Interest and Agency in Institutional Theory. In Institutional Patterns and Organizations Culture and Environment; Ballinger Publishing Company: Pensacola, FL, USA, 1988; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Haveman, H.A.; Rao, H. Structuring a Theory of Moral Sentiments: Institutional and Organizational Coevolution in the Early Thrift Industry. Am. J. Sociol. 1997, 102, 1606–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R.; Ruef, M.; Mendel, P.J.; Caronna, C.A. Institutional Change and Healthcare Organizations: From Professional Dominance to Managed Care; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, J.E.; Duncan, R.B. The Creation of Momentum for Change through the Process of Strategic Issue Diagnosis. Strateg. Manag. J. 1987, 8, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.B.; Clark, S.M.; Gioia, D.A. Strategic Sensemaking and Organizational Performance: Linkages among Scanning, Interpretation, Action, and Outcomes. Acad. Manag. J. 1993, 36, 239–270. [Google Scholar]

- Denison, D.R.; Dutton, J.E.; Kahn, J.A.; Hart, S.L. Organizational Context and the Interpretation of Strategic Issues: A Note on CEO’s Interpretations of Foreign Investment. J. Manag. Stud. 1996, 33, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.A.; Chittipeddi, K. Sensemaking and Sensegiving in Strategic Change Initiation. Strateg. Manag. J. 1991, 12, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.B.; McDaniel Jr, R.R. Interpreting Strategic Issues: Effects of Strategy and the Information-Processing Structure of Top Management Teams. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 286–306. [Google Scholar]

- Peteraf, M.A.; Bergen, M.E. Scanning Dynamic Competitive Landscapes: A Market-Based and Resource-Based Framework. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 1027–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKelvey, B. Organizational Systematics—Taxonomy, Evolution, Classification; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social Capital, Intellectual Capital, and the Organizational Advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, C.M. The Influence of Founding Team Company Affiliations on Firm Behavior. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 741–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fern, M.J.; Cardinal, L.B.; O’Neill, H.M. The Genesis of Strategy in New Ventures: Escaping the Constraints of Founder and Team Knowledge. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 427–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.; Stuart, T. Organizational Endowments and the Performance of University Start-Ups. Manag. Sci. 2002, 48, 154–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.M.; Levinthal, D.A. Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmar, F.; Shane, S. Does Experience Matter? The Effect of Founding Team Experience on the Survival and Sales of Newly Founded Ventures. Strateg. Organ. 2006, 4, 215–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinthal, D.A.; March, J.G. The Myopia of Learning. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, M.; MacMillan, I.C.; Thompson, J.D. Look before You Leap: Market Opportunity Identification in Emerging Technology Firms. Manag. Sci. 2008, 54, 1652–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landier, A.; Thesmar, D. Financial Contracting with Optimistic Entrepreneurs. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2008, 22, 117–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzaga, C.; Tortia, E. Worker Motivations, Job Satisfaction, and Loyalty in Public and Nonprofit Social Services. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2006, 35, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrev, S.D.; Barnett, W.P. Organizational Roles and Transition to Entrepreneurship. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 433–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopp, C. For Better or for Worse?—Nonprofit Experience and the Performance of Nascent Entrepreneurs. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2012, 41, 1251–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruebottom, T. The Microstructures of Rhetorical Strategy in Social Entrepreneurship: Building Legitimacy through Heroes and Villains. J. Bus. Ventur. 2013, 28, 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, C.; Howorth, C. The Language of Social Entrepreneurs. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2008, 20, 285–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotha, R.; George, G. Friends, Family, or Fools: Entrepreneur Experience and Its Implications for Equity Distribution and Resource Mobilization. J. Bus. Ventur. 2012, 27, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, T.E.; Sorenson, O. Liquidity Events and the Geographic Distribution of Entrepreneurial Activity. Adm. Sci. Q. 2003, 48(2), 175–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G.; Simon, H.A. Organizations; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Benner, M.J.; Tripsas, M. The Influence of Prior Industry Affiliation on Framing in Nascent Industries: The Evolution of Digital Cameras. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 277–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, P.J.; Tully, J.C. The Measurement of Role Identity. Soc. Forces 1977, 55, 881–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryker, S.; Burke, P.J. The Past, Present, and Future of an Identity Theory. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2000, 63, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stets, J.E.; Burke, P.J. Identity Theory and Social Identity Theory. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2000, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCall, G.J.; Simmons, J.L. Identities and Interactions: An Examination of Human Associations in Everyday Life; Free Press: New York, NY, USA; Collier-Macmillan: Springfield, OH, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Stryker, S.; Serpe, R.T. Identity Salience and Psychological Centrality: Equivalent, Overlapping, or Complementary Concepts? Soc. Psychol. Q. 1994, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; George, G.; Maltarich, M. Academics or Entrepreneurs? Investigating Role Identity Modification of University Scientists Involved in Commercialization Activity. Res. Policy 2009, 38, 922–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, H.; Porac, J.F. Managing Cognition and Strategy: Issues, Trends and Future Directions. In Handbook of Strategy and Management; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Sauzend Ouks, CA, USA, 2002; p. 165. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D.A.; Thomas, J.B. Identity, Image, and Issue Interpretation: Sensemaking during Strategic Change in Academia. Adm. Sci. Q. 1996, 41, 370–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E.; Jackson, S.E. Categorizing Strategic Issues: Links to Organizational Action. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plambeck, N.; Weber, K. CEO Ambivalence and Responses to Strategic Issues. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 993–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, T.S.; Zeithaml, C.P. The Psychological Context of Strategic Decisions: A Model and Convergent Experimental Findings. Strateg. Manag. J. 1989, 10, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsberg, A.; Venkatraman, N. Institutional Initiatives for Technological Change: From Issue Interpretation to Strategic Choice. Organ. Stud. 1995, 16, 425–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Gedajlovic, E.; Zhang, H. Unpacking Organizational Ambidexterity: Dimensions, Contingencies, and Synergistic Effects. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 781–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.B.; Licht, A.N.; Sagiv, L. Shareholders and Stakeholders: How Do Directors Decide? Strateg. Manag. J. 2011, 32, 1331–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossland, C.; Zyung, J.; Hiller, N.J.; Hambrick, D.C. CEO Career Variety: Effects on Firm-Level Strategic and Social Novelty. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 652–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.S.; Bosse, D.A.; Phillips, R.A. Managing for Stakeholders, Stakeholder Utility Functions, and Competitive Advantage. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, P.S.; Kwon, S.-W. Social Capital: Prospects for a New Concept. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Maruping, L.M.; Takeuchi, R. Disentangling the Effects of CEO Turnover and Succession on Organizational Capabilities: A Social Network Perspective. Organ. Sci. 2006, 17, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaramurthy, C.; Pukthuanthong, K.; Kor, Y. Positive and Negative Synergies between the CEO’s and the Corporate Board’s Human and Social Capital: A Study of Biotechnology Firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 845–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, B.; Zander, U. Knowledge of the Firm, Combinative Capabilities, and the Replication of Technology. Organ. Sci. 1992, 3, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, J.M.; Rauch, A.; Frese, M.; Rosenbusch, N. Human Capital and Entrepreneurial Success: A Meta-Analytical Review. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimeno, J.; Folta, T.B.; Cooper, A.C.; Woo, C.Y. Survival of the Fittest? Entrepreneurial Human Capital and the Persistence of Underperforming Firms. Adm. Sci. Q. 1997, 750–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.L.; Wesley, C.L. Assessing Mission and Resources for Social Change: An Organizational Identity Perspective on Social Venture Capitalists ‘decision Criteria. Entrepreneurship Theory Practice 2010, 34, 705–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, J.C.; Moss, T.W.; Lumpkin, G.T. Research in Social Entrepreneurship: Past Contributions and Future Opportunities. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2009, 3, 161–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defourny, J.; Kuan, Y.-Y.; Bidet, E.; Eum, H.-S. Social Enterprise in South Korea: History and Diversity. Soc. Enterp. J. 2011, 7, 69–85. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.; Wilding, M. Social Enterprise Policy Design: Constructing Social Enterprise in the UK and K Orea. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2013, 22, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, J.H.; Chu, W. The Role of Trustworthiness in Reducing Transaction Costs and Improving Performance: Empirical Evidence from the United States, Japan, and Korea. Organ. Sci. 2003, 14, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]