A Study on the Effects of Waiting Time for Airport Security Screening Service on Passengers’ Emotional Responses and Airport Image

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

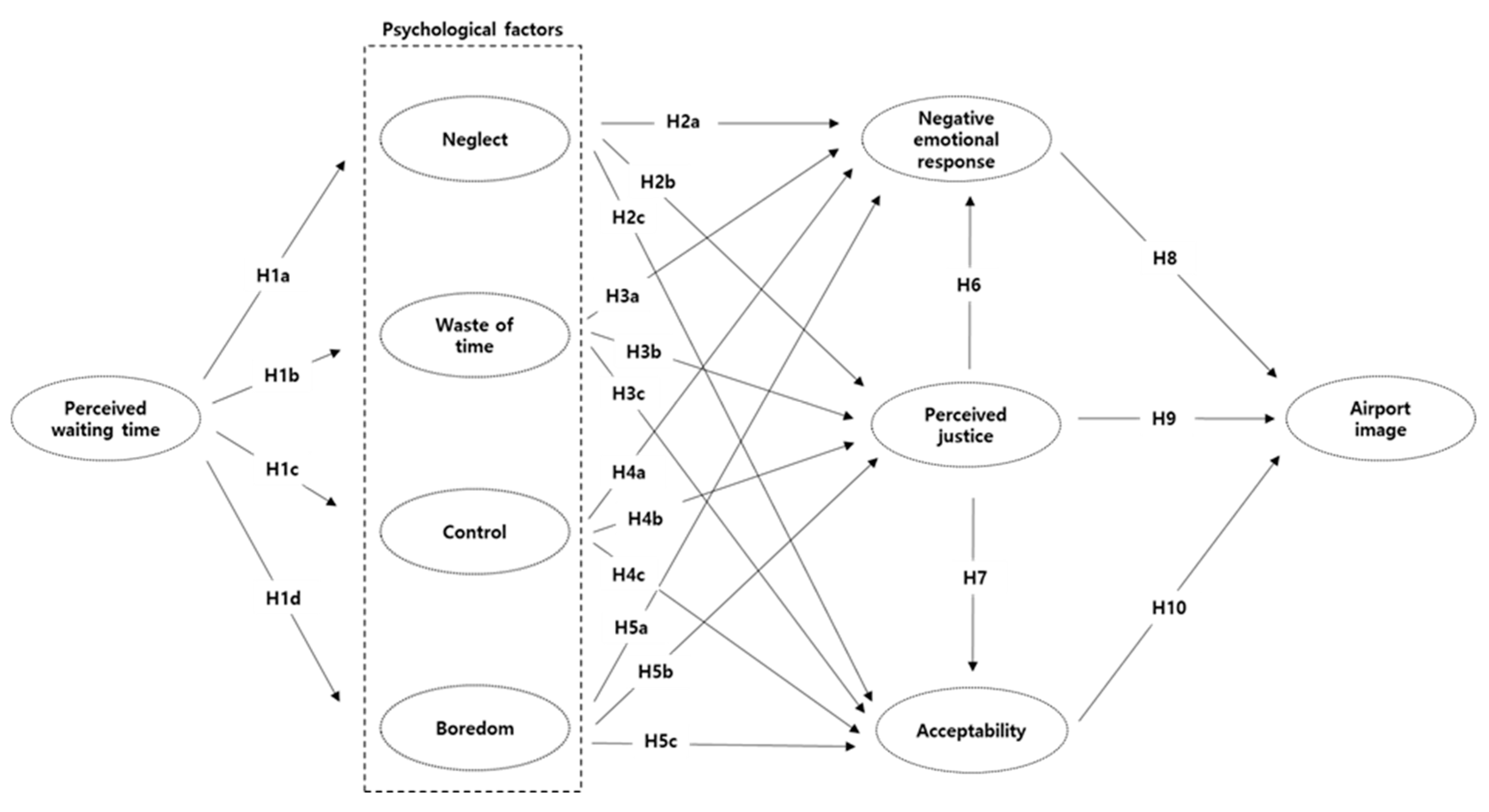

3. Methodology

4. Empirical Analysis

5. Conclusions and Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sakano, R.; Obeng, K.; Fuller, K. Airport security and screening satisfaction: A case study of US. J. Air Trans. Manag. 2016, 55, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkritza, K.; Niemeier, D.; Mannering, F. Airport security screening and changing passenger satisfaction: An exploratory assessment. J. Air Trans. Manag. 2006, 12, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindhav, B.; Holland, J.; Rodie, A.R.; Adidam, P.T.; Pol, L.G. The impact of perceived fairness on satisfaction: Are airport security measures fair? Does it matter? J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2006, 14, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.K.; Yu, Y.W.; Batnasan, J. Services innovation impact to customer satisfaction and customer value enhancement in airport. In Proceedings of the PICMET’14 Conference: Portland International Center for Management of Engineering and Technology, Infrastructure and Service Integration, Kanazawa, Japan, 27–31 July 2014; pp. 3344–3357, ISBN 978-1-890843-29-8. [Google Scholar]

- Garrick, B.J.; Hall, J.E.; Kilger, M.; McDonald, J.C.; O’Toole, T.; Probst, P.S.; Zebroski, E.L. Confronting the risks of terrorism: Making the right decisions. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2004, 86, 129–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornik, J. Subjective vs. objective time measures: A note on the perception of time in consumer behavior. J. Consum. Res. 1984, 11, 615–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. The Effect of Waiting Environment of Airline Service on Perceived Waiting Time and Service Quality. Ph.D. Thesis, Kyonggi University, Suwon-si, Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.A.; Baker, T.L. An assessment of the relationship between service quality and customer satisfaction in the formation of consumers’ purchase intentions. J. Retail. 1994, 70, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, R.C.; Larson, B.M.; Katz, K.L. Prescription for waiting–in line blues: Entertain, enlighten and engage. Sloan Manag. Rev. (Winter) 1991, 32, 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Folkes, V.S.; Koletsky, S.; Graham, J.L. A field study of causal inferences and consumer reaction: The view from the airport. J. Cons. Res. 1987, 13, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, R.C. OR forum—Perspectives on queues: Social justice and the psychology of queueing. Oper. Res. 1987, 35, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, W.; Lambert, C.U. Impact of waiting time on evaluation of service quality and customer satisfaction in foodservice operations. Foodserv. Res. Intl. 2000, 12, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, M.K.; Tse, D.K. What to tell consumers in waits of different lengths: An integrative model of service evaluation. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.M.; Vollmann, T.E. A framework for relating waiting time and customer satisfaction in a service operation. J. Serv. Mark. 1990, 4, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, K.A.; Kimes, S.E.; Lynn, M.; Pullman, M.E.; Lloyd, R.C. A framework for evaluating the customer wait experience. J. Serv. Manag. 2010, 21, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. J. Mark. 1985, 49, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellaris, J.J.; Kent, R.J. The influence of music on consumers’ temporal perceptions: Does time fly when you’re having fun? J. Consum. Psychol. 1992, 1, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuna, E.E. The psychological cost of waiting. J. Math. Psychol. 1985, 29, 82–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonides, G.; Verhoef, P.C.; Van Aalst, M. Consumer perception and evaluation of waiting time: A field experiment. J. Consum. Psychol. 2002, 12, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, M.K.; Bateson, J.E. Testing a theory of crowding in the service environment. ACR N. Am. Adv. 1990, 17, 866–873. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, V.L. Intuitive Psychologist or Intuitive Lawyer? Alternative Model of the Attribution Process. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 767–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, M.; Gilliland, S.W. Having to wait for service: Customer reactions to delays in service delivery. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 55, 107–129. [Google Scholar]

- Maister, D.H. The Psychology of Waiting Lines, The Service Encounter; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1985; pp. 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Klapp, O.E. Overload and Boredom: Essays on the Quality of Life in the Information Society; Greenwood Publishing Group Inc.: Westpotr, CT, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Zakay, D. Subjective time and attentional resource allocation: An integrated model of time estimation. Adv. Psychol. 1989, 59, 365–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. Waiting for service: The relationship between delays and evaluations of service. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Gopinath, M.; Nyer, P.U. The role of emotions in marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1999, 27, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, M.B.; Bettencourt, L.A.; Wenger, S. The relationship between waiting in a service queue and evaluations of service quality: A field theory perspective. Psychol. Mark. 1998, 15, 735–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.S. The effect of waiting time on service evaluation. Korean J. Mark. 2000, 15, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S.; Kim, S. The effects of waiting time on service quality evaluation and goodwill at medical service encounter. Asia Mark. J. 2003, 5, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Dube-Rioux, L.; Schmitt, B.H.; Leclerc, F. Consumers’ reactions to waiting: When delays affect the perception of service quality. ACR N. Am. Adv. 1989, 16, 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, M.P. Mood states and consumer behavior: A critical review. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, T.W. What drives customer loyalty with complaint resolution? J. Serv. Res. 1999, 1, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiders, K.; Berry, L.L. Service fairness: What it is and why it matters. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1998, 12, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park. Effect of Perceived Waiting Time and Service Production Time on Quality Evaluation. J. Korean Consum. Cult. Assoc. 1999, 2, 109–133. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, K. How the Psychological Response Caused by the Perceived Waiting Time Affects Negative Emotions, Acceptability and Service Evaluation. Ph.D. Thesis, Kyonggi University, Suwon, Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Park, G. The Effects of Servicescape in an Airport Passenger Terminal: A Case Study on Incheon International Airport. Ph.D. Thesis, Korea Aerospace University, Goyang, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Padgett, D.; Allen, D. Communicating experiences: A narrative approach to creating service brand image. J. Advert. 1997, 26, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, M.L. Negative word-of-mouth by dissatisfied consumers: A pilot study. J. Mark. 1983, 47, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, Y. The Effect of Perceived Waiting Time on Negative Emotion, Acceptability, Service Evaluation and Word-of-Mouth Intention. Ph.D. Thesis, Graduate School of SeoKyeong University, Seoul, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, K.; Kim, G. A study on the relationship among the psychological response, negative emotions, accommodation possibility and service evaluation cause by perceived witing time: The case of hotel and brand coffee shops. J. Hotel Adm. 2013, 22, 253–274. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, E. The Influence of Disconfirmation between Expected Waiting Time and Actual Waiting Time on Justice, Acceptability and Emotional Response: Focused on Social Judgement Theory. Ph.D. Thesis, The Graudate School of Gachon University, Gyeonggi-do, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Hall, J.; Shaw, M.; Crisp, M. Marketing Research an Applied Orientation; Prentice-Hall: Sydney, Australia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis (Vol. 5. No. 3. pp. 207–219); Upper Prentice hall: Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Segars, A.H.; Grover, V. Strategic information systems planning success: An investigation of the construct and its measurement. MIS Q. 1998, 22, 139–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fiIt. In Testing Structural Equations Models; Bollen, K.A., Long, J.S., Eds.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

| Measures | Variables | Related Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived waiting time | Before my arrival at the airport, I expected that I would need to wait for security screening service. | McGuire et al. [15] Kim [40] Jung [41] |

| I felt that I waited for a long time to get security screening service. | ||

| Waiting time for security screening service was longer than expected. | ||

| Neglect | I was given guidance about waiting time for security screening service. | |

| I was given relevant information while waiting for security screening service. | ||

| I felt that I was given caring while waiting for security screening service. | ||

| Waste of time | I think that waiting for security screening service wastes time. | |

| Waiting for security screening service robbed me of time to do something else. | ||

| I think that waiting for security screening service reduced time to do my shopping in duty-free shops. | ||

| Control | I think that the causes of waiting time for security screening service can be controlled. | |

| I think that waiting time for security screening service can be reduced. | ||

| I think that the passengers waiting for security screening service were well managed. | ||

| Boredom | It was unpleasant to wait for security screening service. | |

| I had nothing to do while waiting for security screening service. | ||

| I was bored while waiting for security screening service. | ||

| Negative emotional response | I was dissatisfied with waiting for security screening service. | Jung [40] Sun [42] Park [35] |

| I was annoyed at waiting for security screening service. | ||

| I was angry at waiting for security screening service. | ||

| Perceived justice | Waiting for security screening service was based on justice. | |

| I think the procedure of security screening service was generally just. | ||

| I think that the security screening personnel was professional. | ||

| Acceptability | Waiting time for security screening service was acceptable. | |

| I can also accept waiting time for security screening service in the future. | ||

| I accept I need to wait for security screening service. | ||

| Airport image | I regard the airport as positive. | |

| The airport is friendly to passengers. | ||

| I like the airport image in general. |

| Division | Frequency (Persons) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 143 | 51.1 |

| Female | 137 | 48.9 | |

| Age (years) | ≤19 | 4 | 1.4 |

| 20s | 93 | 33.2 | |

| 30s | 73 | 26.1 | |

| 40s | 40 | 14.3 | |

| 50s | 45 | 16.1 | |

| ≥60 | 25 | 8.9 | |

| Education | ≤High school graduate | 36 | 12.9 |

| College student | 63 | 22.5 | |

| College graduate | 154 | 55.0 | |

| ≥Graduate school student | 27 | 9.6 | |

| Occupation | Student | 36 | 12.9 |

| Government official | 25 | 8.9 | |

| Company employee | 78 | 27.9 | |

| Professional | 56 | 20.0 | |

| Self-employed | 23 | 8.2 | |

| Housewife | 25 | 8.9 | |

| Other | 37 | 13.2 | |

| Number of air travels | 1–2 | 154 | 55.0 |

| 3–4 | 72 | 25.7 | |

| 5–6 | 20 | 7.1 | |

| 7–8 | 12 | 4.3 | |

| 9–10 | 9 | 3.2 | |

| ≥11 | 13 | 4.6 | |

| Purpose of airport use | Domestic tourism | 141 | 50.4 |

| Overseas trip | 139 | 49.6 | |

| Airline utilized recently | FSC | 108 | 38.6 |

| LCC | 172 | 61.4 |

| Factor | Kolmogorov–Smirnov a | Shapiro–Wilk | Mean | Std. Dev | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Df | Sig. | Statistic | Df | Sig. | |||

| Perceived waiting time | 0.194 | 280 | 0.000 | 0.940 | 280 | 0.000 | 3.511 | 0.703 |

| Neglect | 0.270 | 280 | 0.000 | 0.876 | 280 | 0.000 | 2.500 | 0.747 |

| Waste of time | 0.223 | 280 | 0.000 | 0.924 | 280 | 0.000 | 2.529 | 0.863 |

| Boredom | 0.213 | 280 | 0.000 | 0.917 | 280 | 0.000 | 3.831 | 0.679 |

| Negative emotional response | 0.146 | 280 | 0.000 | 0.954 | 280 | 0.000 | 2.645 | 0.755 |

| Perceived justice | 0.303 | 280 | 0.000 | 0.823 | 280 | 0.000 | 3.582 | 0.678 |

| Acceptability | 0.206 | 280 | 0.000 | 0.883 | 280 | 0.000 | 3.557 | 0.600 |

| Airport image | 0.163 | 280 | 0.000 | 0.926 | 280 | 0.000 | 3.527 | 0.639 |

| Factor | Variables | Standardized Loadings | Loadings | S.E a | C.R b | SMC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived waiting time | A1 | 0.865 | 1.024 | 0.092 | 11.155 *** | 0.749 |

| A2 | 0.831 | 1.000 | Fix | Fix | 0.691 | |

| Neglect | B1 | 0.715 | 1.000 | Fix | Fix | 0.511 |

| B2 | 0.966 | 1.336 | 0.196 | 6.803 *** | 0.933 | |

| Waste of time | C1 | 0.824 | 1.000 | Fix | Fix | 0.678 |

| C2 | 0.865 | 1.093 | 0.095 | 11.553 *** | 0.749 | |

| Boredom | D1 | 0.844 | 1.024 | 0.073 | 14.008 *** | 0.713 |

| D2 | 0.937 | 1.176 | 0.081 | 14.526 *** | 0.877 | |

| D3 | 0.735 | 1.000 | Fix | Fix | 0.540 | |

| Negative emotional response | E1 | 0.871 | 1.000 | Fix | Fix | 0.759 |

| E2 | 0.931 | 1.042 | 0.050 | 20.751 *** | 0.867 | |

| E3 | 0.795 | 1.872 | 0.053 | 16.542 *** | 0.632 | |

| Perceived justice | F1 | 0.937 | 1.000 | Fix | Fix | 0.878 |

| F2 | 0.899 | 1.922 | 0.059 | 15.569 *** | 0.809 | |

| Acceptability | G1 | 0.814 | 1.015 | 0.073 | 13.923 *** | 0.814 |

| G2 | 0.902 | 1.107 | 0.074 | 15.008 *** | 0.690 | |

| G3 | 0.767 | 1.000 | Fix | Fix | 0.589 | |

| Airport image | H1 | 0.816 | 1.000 | Fix | Fix | 0.666 |

| H2 | 0.777 | 1.063 | 0.079 | 13.417 *** | 0.604 | |

| H3 | 0.846 | 1.131 | 0.079 | 14.332 *** | 0.716 |

| Construct | AVE(Fornell) | AVE(Hair) | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived waiting time | 0.779 | 0.719 | 0.876 |

| Neglect | 0.797 | 0.722 | 0.885 |

| Wasted time | 0.742 | 0.714 | 0.852 |

| Boredom | 0.803 | 0.710 | 0.924 |

| Negative emotional response | 0.817 | 0.752 | 0.930 |

| Perceived justice | 0.916 | 0.843 | 0.956 |

| Acceptability | 0.826 | 0.688 | 0.934 |

| Airport image | 0.787 | 0.662 | 0.917 |

| Construct | Perceived Waiting Time | Neglect | Wasted Time | Boredom | Negative Emotional Response | Perceived Justice | Acceptability | Airport Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived waiting time | 1 | |||||||

| Neglect | 0.003 | 1 | ||||||

| Wasted time | 0.189 | 0.014 | 1 | |||||

| Boredom | 0.118 | 0.094 | 0.091 | 1 | ||||

| Negative emotional response | 0.253 | 0.046 | 0.383 | 0.084 | 1 | |||

| Perceived justice | 0.016 | 0.033 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.006 | 1 | ||

| Acceptability | 0.158 | 0.010 | 0.072 | 0.007 | 0.182 | 0.245 | 1 | |

| Airport image | 0.002 | 0.052 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.008 | 0.235 | 0.194 | 1 |

| Hypothesis Path | Standardized Estimate | C.R. b | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | Perceived waiting time → Neglect | −0.212 | −2.770 *** | Supported |

| H1b | Perceived waiting time → Waste of time | 0.606 | 6.542 *** | Supported |

| H1d | Perceived waiting time → Boredom | 0.499 | 5.893 *** | Supported |

| H2a | Neglect → Negative emotional response | −0.116 | −2.178 * | Supported |

| H2b | Neglect → Perceived justice | 0.195 | 3.070 *** | Supported |

| H2c | Neglect → Acceptability | −0.029 | −0.514 | Not Supported |

| H3a | Waste of time → Negative emotional response | 0.617 | 8.815 *** | Supported |

| H3b | Waste of time → Perceived justice | −0.077 | −1.072 | Not Supported |

| H3c | Waste of time → Acceptability | −0.291 | −4.340 *** | Supported |

| H5a | Boredom → Negative emotional response | 0.072 | 1.251 | Not Supported |

| H5b | Boredom → Perceived justice | 0.088 | 1.294 | Not Supported |

| H5c | Boredom → Acceptability | −0.016 | −0.267 | Not Supported |

| H6 | Perceived justice → Negative emotional response | −0.022 | −0.395 | Not Supported |

| H7 | Perceived justice → Acceptability | 0.477 | 7.224 *** | Supported |

| H8 | Negative emotional response → Airport image | 0.051 | 0.842 | Not Supported |

| H9 | Perceived justice → Airport image | 0.353 | 4.844 *** | Supported |

| H10 | Acceptability → Airport image | 0.283 | 3.762 *** | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, M.H.; Park, J.W.; Choi, Y.J. A Study on the Effects of Waiting Time for Airport Security Screening Service on Passengers’ Emotional Responses and Airport Image. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10634. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410634

Kim MH, Park JW, Choi YJ. A Study on the Effects of Waiting Time for Airport Security Screening Service on Passengers’ Emotional Responses and Airport Image. Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10634. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410634

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Mun Hwan, Jin Woo Park, and Yu Jin Choi. 2020. "A Study on the Effects of Waiting Time for Airport Security Screening Service on Passengers’ Emotional Responses and Airport Image" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10634. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410634