Co-Creating Value in Sustainable and Alternative Food Networks: The Case of Community Supported Agriculture in New Zealand

Abstract

:1. Introduction

The Community Supported Agriculture Format

- -

- What activities are involved on the farms, from both consumers and producers, and how do these activities involve time, space and objects?

- -

- What are the different values invoked in this CSA format, from both consumers’ and producers’ perspectives?

- -

- What are the meanings attributed to the co-creation processes involved in this CSA format, by both consumers and producers?

2. Materials and Methods

3. Findings

3.1. The CSA Farm from the Inside: The Role of the Garden as a Stage

“It is a combination between the physical elements and other elements, like people and marketing”(Farmer 1, man)

“We are trying to do something simple, grow food, and provide it to people, but other things happen in the middle and the result is usually positive and the unexpected part from that is interesting”(Farmer 1, man)

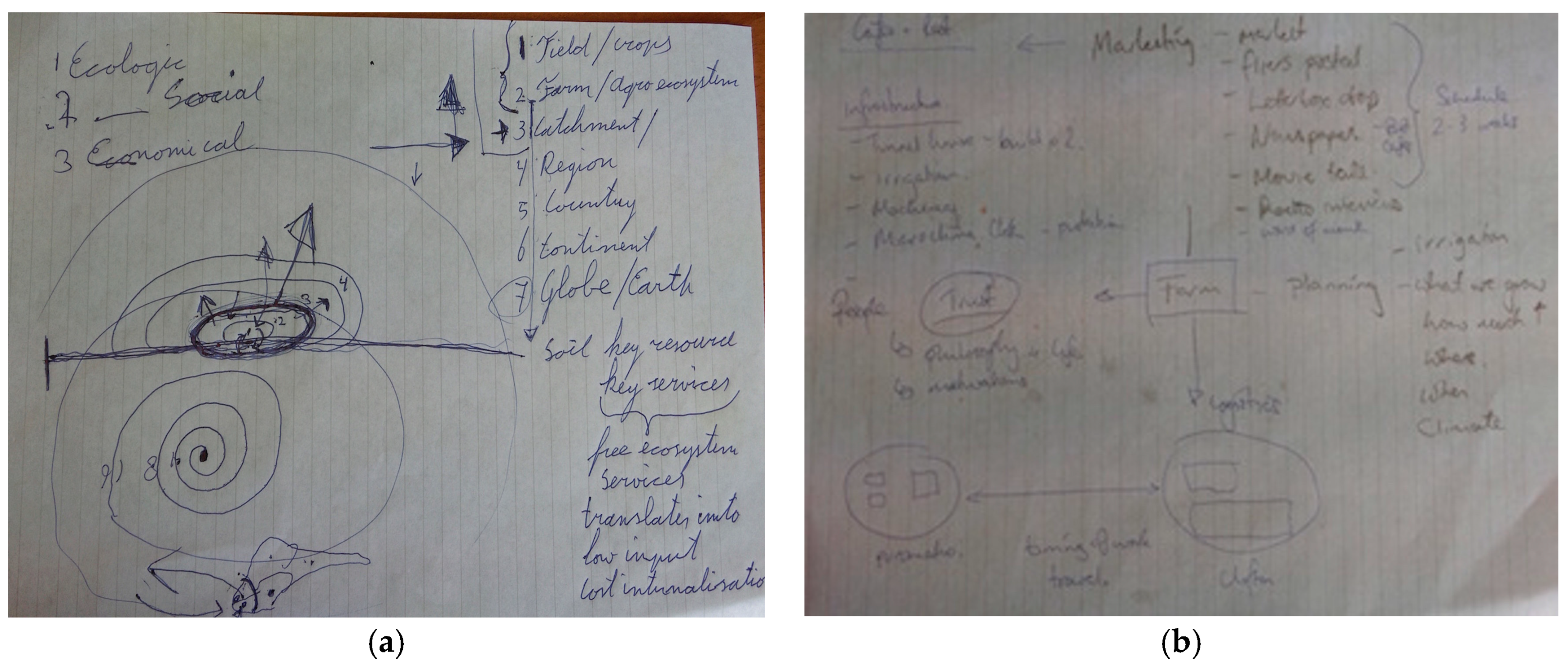

“The soil is my key resource, but also it provides the key services to the field or the crop and you can also put the social and the economic level, we work on that…”(Farmer 2, man)

3.2. The Social Value: The Experience to Be Connected through Food

“An opportunity for people from different philosophies and ideas to interact to each other, so people come to pick up the vegetables and they will probably meet there and start talking about their lives. This social element is an extra intangible element that we can’t predict but happens by putting people together”.(Farmer 1, man)

“The CSA is something I wanted to be a part of, especially the positive environmental outcomes”(Consumer 1, woman)

“I joined the farm because there I found a community of similar minded people who can share ideas and experiences”(Consumer 5, man)

“The CSA is a safe place where people can come together to support each other in the desire to create good food”.(Consumer 8, woman)

“The knowledge is a key aspect, how to harvest or cook the vegetables, but also knowledge within the members, so every person has different knowledge so they can share”.(Farmer 2, man)

“We have a commitment, a sort of mutual arrangement, they are committed to pay and we to supply. But also we need to help them, we give them recipes and we also ask them their preferences, is support rather than “here are your zucchini and deal with them”. Having a relationship with people is providing also some suggestions”.(Farmer 1, man)

“One of the motivation that pushed me to approach to the CSA is to improve my personal knowledge about storing and preparing fresh food. The weekly newsletter has been very helpful and informative. They provide new and exciting things to try and then tell us how to use them. The education point is really important for us”.(Consumer 8, woman)

“The friendliness and connection we can have with people growing our food is an important aspect. Buying from the supermarket is just not the same! There you are lucky if you know which country the produce comes from, let alone which region or farm. Being a part of the CSA, I have a relationship with the people who are out on the land, planting, tending and harvesting what ends up on our plates. This is so much more direct that the other food buying options”.(Consumer 2, man)

“We originally started with the CSA because we lived in this community but we didn’t know anyone, and we wanedt to get in contact with people, to get known by new neighbors and to build a sense of community”.(Consumer 5, man)

3.3. The Economic Value: To Be a Part of the Exchange

“The system externalizes the costs because of the diversity required, but this farm aims at internalizing the costs, to have a low input agro-ecological farm, and the farm sustains itself. … all the money we spend we spend locally to sustain our economic system”.(Farmer 2, man)

“We are trying to break the chain of the industrialized farming by making a network of local farming communities that are self sustainable”.(Farmer 2, man)

“… for me it is important also the fact that they come and pick up, we are not exchanging money, that’s just a kind to give them, it’s really nice, because at the market it’s like “ten dollars”, but I really enjoy this giving to them”.(Farmer 1, man)

“The consumers feel as though they have a bit of ownership, they come to the farm and they show off “this is the place where my vegetables are grown”, because they are so proud of that, and it is nice, they feel so passionate about the farm.”(Farmer 1, man)

3.4. The Environmental Value: Resilience to Promote a Better Future

“Being able to be sustainable in what we are growing, local, in a small area, and also to have a system that you are growing each year and you are not depriving it. I guess also resilience is related to the variety of different things we can produce in this way, so if you grow just one kind of thing you don’t probably have the ability to survive…”(Farmer 3, woman)

“Lower direct environmental impacts: This is the most important for me. The farm’s approach is much kinder on the immediate environment. Impacts, such as depletion of soil, overuse of water, loss of soil biodiversity, nutrient runoff and pollution, are all lower than for conventional farming. I think these types of effects should be avoided so we can live in a healthier and more bio-diverse country.”(Consumer 14, woman)

“There are a raft of environmentally destructive and unnecessary practices that are embedded in the conventional/factory food production system and I support the CSA as an alternative to that system.”(Consumer 10, man)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Birchall, J. The potential of co-operatives during the current recession; theorizing comparative advantage. J. Entrepeneurial Organ. Divers. 2013, 2, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fotaki, M. Co-Production under the Financial Crisis and Austerity: A Means of Democratizing Public Services or a Race to the Bottom? J. Manag. Inq. 2015, 24, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, C.A. Community resilience and contemporary agri-ecological systems: Reconnecting people and food, and people with people. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2008, 25, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. The impact of the financial-economic crisis on sustainability transitions: Financial investment, governance and public discourse. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2013, 6, 67–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akaka, M.A.; Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. An Exploration of Networks in Value Cocreation: A Service-Ecosystems View. In Special Issue–Toward a Better Understanding of the Role of Value in Markets and Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2012; Volume 9, pp. 13–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrichs, H. Sharing economy: A potential new pathway to sustainability. Gaia 2013, 22, 228–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullstrand Edbring, E.; Lehner, M.; Mont, O. Exploring consumer attitudes to alternative models of consumption: Motivations and barriers. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 123, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C. Value co-creation in service logic: A critical analysis. Mark. Theory 2011, 11, 279–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ind, N.; Coates, N. The meanings of co-creation. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2013, 25, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lush, R.F. Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spohrer, J.; Maglio, P.P.; Bailey, J.; Gruhl, D. Steps toward a science of service systems. Computer 2007, 40, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shove, E.; Pantzar, M.; Watson, M. The Dynamics of Social Practice: Everyday Life and How It Changes; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paek, H.J.; Nelson, M.R. To buy or not to buy: Determinants of socially responsible consumer behavior and consumer reactions to cause-related and boycotting ads. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2009, 31, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frow, P.; McColl-Kennedy, J.R.; Hilton, T.; Davidson, A.; Payne, A.; Brozovic, D. Value propositions: A service ecosystems perspective. Mark. Theory. 2014, 14, 327–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carù, A.; Cova, B. Co-creating the collective service experience. J. Serv. Manag. 2015, 26, 276–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verneau, F.; La Barbera, F.; Amato, M.; Sodano, V. Consumers’ concern towards palm oil consumption: An empirical study on attitudes and intention in Italy. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 1982–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.; Goddard, E.; Farmer, A. How knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs impact dairy anti-consumption. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 2304–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Annual Report. 2016. Available online: https://www.unenvironment.org/annualreport/2016/assets/pdf/PPR_2016_final.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2017).

- Rezai, G. Consumers’ awareness and consumption intention towards green foods. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 6, 4496–4503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B. Embodied connections: Sustainability, food systems and community gardens. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.K.; Sobal, J. Consumer food system participation: A community analysis. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2014, 53, 579–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer, B. Political consumerism between individual choice and collective action: Social movements, role mobilization and signalling. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2006, 30, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, S.; Migliore, G.; Schifani, G.; Schimmenti, E.; Padel, S. Motives for buying local, organic food through English box schemes. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 1600–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knickel, K.; Brunori, G.; Rand, S.; Proost, J. Towards a better conceptual framework for innovation processes in agriculture and rural development: From linear models to systemic approaches. J. Agr. Educ. Ext. 2009, 15, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mount, P. Growing local food: Scale and local food systems governance. Agric. Hum. Values 2012, 29, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, S.M. Food miles, local eating, and community supported agriculture: Putting local food in its place. Agric. Hum. Values 2013, 30, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renting, H.; Schermer, M.; Rossi, A. Building Food Democracy: Exploring Civic Food Networks and Newly Emerging Forms of Food Citizenship. Int. J. Sociol. Agric. Food 2012, 19, 289–307. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon, A.H. Community Supported Agriculture: A Conceptual Model of Health Implications. Austin J Nutri Food Sci. 2014, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Forssell, S.; Lankoski, L. The sustainability promise of alternative food networks: An examination through “alternative” characteristics. Agric. Hum. Values 2014, 32, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whatmore, S.; Clark, N. Good Food: Ethical Consumption and Global Change. In A World in the Making; Clark, N., Massey, D., Sarre, P., Eds.; The Open University: Milton Keynes, UK, 2006; pp. 363–412. [Google Scholar]

- Renting, H.; Marsden, T.K.; Banks, J. Understanding alternative food networks: Exploring the role of short food supply chains in rural development. Environ. Plan. A 2003, 35, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carey, S.; Lawson, B.; Krause, D.R. Social capital configuration, legal bonds and performance in buyer–supplier relationships. J. Operat. Manag. 2011, 29, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Demartini, M.; Orlandi, I.; Tonelli, F.; Anguitta, D. A manufacturing value modeling methodology (mvmm): A value mapping and assessment framework for sustainable manufacturing. In Sustainable Design and Manufacturing 2017; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 68. [Google Scholar]

- Malagon-Zaldua, E.; Begiristain-Zubillaga, M.; Onederra-Aramendi, A. Measuring the economic impact of farmers’ markets on local economies in the basque country. Agriculture 2018, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Witzling, L.; Shaw, B.R. Lifestyle segmentation and political ideology: Toward understanding beliefs and behavior about local food. Appetite 2019, 132, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Rodríguez, K.A.; Álvarez-Ávila, M.D.C.; Hernández Castillo, F.; Schwentesius Rindermann, R.; Figueroa-Sandoval, B. Farmers’ market actors, dynamics, and attributes: A bibliometric study. Sustainability 2018, 11, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, H.; Gibson, K.E.; Wright, K.G.; Neal, J.A.; Sirsat, S.A. Food safety and food quality perceptions of farmers’ market consumers in the United States. Food Control. 2017, 79, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pokorná, J.; Pilař, L.; Balcarová, T.; Sergeeva, I. Value Proposition Canvas: Identification of Pains, Gains and Customer Jobs at Farmers’ Markets. AGRIS On-Line Pap. Econ. Inf. 2015, 7, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McNeill, L.; Hale, O. Who shops at local farmers’ markets? Committed loyals, experiencers and produce-orientated consumers. Aust. Mark. J. 2016, 24, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Scott, S. Rural development strategies and government roles in the development of farmers’ cooperatives in China. J. Agric. Food Syst. Commun. Dev. 2014, 4, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Russell, W.S.; Zepeda, L. The adaptive consumer: Shifting attitudes, behavior change and CSA membership renewal. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2008, 23, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardesty, S.D.; Leff, P. Determining marketing costs and returns in alternative marketing channels. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2010, 25, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ginn, F. Dig for victory! New histories of wartime gardening in Britain. J. Hist. Geogr. 2012, 38, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimpo, N.; Wesener, A.; McWilliam, W. How community gardens may contribute to community resilience following an earthquake. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 38, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyg, P.M.; Christensen, S.; Peterson, C.J. Community gardens and wellbeing amongst vulnerable populations: A thematic review. Health Promot. Int. 2019, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mmako, N.J.; Capetola, T.; Henderson-Wilson, C. Sowing social inclusion for marginalised residents of a social housing development through a community garden. Health Prom. J. Austr. 2019, 30, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liamputtong, P.; Sanchez, E.L. Cultivating Community: Perceptions of Community Garden and Reasons for Participating in a Rural Victorian Town. Act. Adapt. Aging 2018, 42, 124–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, H.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y. Community-Engaged Research for the Promotion of Healthy Urban Environments: A Case Study of Community Garden Initiative in Shanghai, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nova, P.; Pinto, E.; Chaves, B.; Silva, M. Growing health and quality of life: Benefits of urban organic community gardens. J. Nutr. Health Food Sci. 2018, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, R. Sustainability: Through cross-cultural community garden activities. Local Environ. 2019, 24, 762–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, L.W.; Jenerette, G.D. Biodiversity and direct ecosystem service regulation in the community gardens of Los Angeles, CA. Landsc. Ecol. 2015, 30, 637–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliore, G.; Forno, F.; Guccione, G.D.; Schifani, G. Food Community Networks as sustainable self-organized collective action: A case study of a solidarity purchasing group. New Medit 2014, 13, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, P.R.; Forno, F. Political consumerism and new forms of political participation: The Gruppi di Acquisto Solidale in Italy. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 2012, 644, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestripieri, L.; Toa, G.; Antonello, P. Solidarity Purchasing Groups in Italy: A critical assessment of effects on the marginalisation of their suppliers. Int. J. Soc. Agric. Food 2018, 24, 393–412. [Google Scholar]

- Brunori, G.; Rossi, A.; Guidi, F. On the new social relations around and beyond food. Analysing consumers’ role and action in Gruppi di Acquisto Solidale (Solidarity Purchasing Groups). Sociol. Rural. 2012, 52, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, S.M. Food With a Farmer’s Face: Community-Supported Agriculture in the United States. Geogr. Rev. 2007, 97, 550–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Miller, S. The impacts of local markets: A review of research on farmers markets and community supported agriculture (CSA). Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2008, 90, 1296–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cone, C.; Myhre, A. Community-Supported Agriculture: A Sustainable Alternative to Industrial Agriculture? Hum. Organ. 2000, 59, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turinek, M.; Grobelnik-Mlakar, S.; Bavec, M.; Bavec, F. Biodynamic agriculture research progress and priorities. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2009, 24, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.J.; Coskuner-Balli, G. Enchanting ethical consumerism: The case of community supported agriculture. J. Consum. Cult. 2007, 7, 275–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzani, C.; Canavari, M. Alternative Agri-Food Networks and Short Food Supply Chains: A review of the literature. Econ. Agro-Aliment. 2013, 2, 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, K. The Changing Face of Community Supported Agriculture. Cult. Agric. 2010, 32, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuPuis, E.M.; Goodman, D. Should we go “home” to eat? Toward a reflexive politics of localism. J. Rural Stud. 2005, 21, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, B.L.; Gradwell, S.; Yoder, R. Growing food, growing community: Community supported agriculture in rural Iowa. Commun. Dev. J. 1999, 34, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloppenburg, J.; Hendrickson, J.; Stevenson, G.W. Coming in to the foodshed. Agric. Hum. Values 1996, 13, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, J.; Imerman, E.; Peters, G. Community Supported Agriculture (CSA): Building Community Among Farmers and Non-Farmers. J. Ext. 2002, 40, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Carolan, M. More-than-Active Food Citizens: A Longitudinal and Comparative Study of Alternative and Conventional Eaters. Rural Sociol. 2017, 82, 197–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzoli, K. Sustainable development: A transdisciplinary overview of the literature. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 1997, 40, 549–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, D.J. Organic agriculture and food security: A decade of unreason finally implodes. F. Crop. Res. 2018, 225, 128–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamine, C. Sustainability and resilience in agrifood systems: Reconnecting agriculture, food and the environment. Sociol. Rural. 2015, 55, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wezel, A.; Goette, J.; Lagneaux, E.; Passuello, G.; Reisman, E.; Rodier, C.; Turpin, G. Agroecology in Europe: Research, education, collective action networks, and alternative food systems. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zsolnai, L. Ethics, Meaning, and Market Society; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan Uribe, A.L.; Winham, D.M.; Wharton, C.M. Community supported agriculture membership in Arizona. An exploratory study of food and sustainability behaviours. Appetite 2012, 59, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanein, N. Locating food democracy: Theoretical and practical ingredients. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2008, 3, 286–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, J.L.; Farrell, T.J.; Rangarajan, A. Linking vegetable preferences, health and local food systems through community-supported agriculture. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2392–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascucci, S.; Dentoni, D.; Lombardi, A.; Cembalo, L. Sharing values or sharing costs? Understanding consumer participation in alternative food networks. NJAS Wagening J. Life Sci. 2016, 78, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galt, R.E.; Bradley, K.; Christensen, L.O.; Munden-Dixon, K. The (un)making of “CSA people”: Member retention and the customization paradox in Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) in California. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 65, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tuli, F. The basis of distinction between qualitative and quantitative research in social science: Reflection on ontological, epistemological and methodological perspectives. Ethiop. J. Educ. Sci. 2010, 6, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Solomon, M.R. The Role of Products as Social Stimuli: A Symbolic Interactionism Perspective. J. Consum. Res. 1983, 10, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD Better Life Index. Available online: http://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/#/11111111111 (accessed on 5 August 2017).

- OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: New Zealand 2017. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/newzealand/oecd-environmental-performance-reviews-new-zealand-2017-9789264268203-en.htm (accessed on 5 August 2017).

- New Zealander’s Ministry for the Environment & Stats NZ. New Zealand’s Environmental Reporting Series: Our land 2018. Available online: https://www.mfe.govt.nz/sites/default/files/media/RMA/Our-land-201-final.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2019).

- Community Supported Agriculture Australia and New Zealand. Available online: http://www.csanetworkausnz.org (accessed on 15 December 2019).

- Schutz, A. The Phenomenology of the Social World; Northwestern University Press: Evanston, IL, USA, 1967; p. 225. [Google Scholar]

- Crozier, G.; Denzin, N.; Lincoln, Y. Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000; 1144p. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, W.J. An Analysis of Thinking and Research About Qualitative Methods; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, E.V.; Higginbottom, G. The use of focused ethnography in nursing research. Nurse Res. 2013, 20, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roper, J.M.; Shapira, J. Ethnography in Nursing Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000; 160p. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; p. 472. [Google Scholar]

- Higginbottom, G.M. The transitioning experiences of internationally-educated nurses into a Canadian health care system: A focused ethnography. BMC Nurs. 2011, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bagnoli, A. Beyond the standard interview: The use of graphic elicitation and arts-based methods. Qual. Res. 2009, 9, 547–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holloway, I. Basic Concepts for Qualitative Research, 1st ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1997; p. 186. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, A.; Elliott, R. The evolution of the empowered consumer. Eur. J. Mark. 2006, 40, 1106–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrier, H. Anti-consumption discourses and consumer-resistant identities. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blanchard, A.L.; Carolina, N.; Markus, M.L. The experienced “sense” of a virtual community: Characteristics and processes. Data Base Adv. Inf. Syst. 2004, 35, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cova, B.; Dalli, D. The Linking Value in Experiential Marketing: Acknowledging the Role of Working Consumers. In The SAGE Handbook of Marketing Theory; Russel Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 476–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1595–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglioni, C.; Lozza, E.; Bosio, A.C. Lay People Representations on the Common Good and Its Financial Provision. Sage Open 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spaargaren, G.; Oosterveer, P. Citizen-consumers as agents of change in globalizing modernity: The case of sustainable consumption. Sustainability 2010, 2, 1887–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bettiga, D.; Ciccullo, F. Co-creation with customers and suppliers: An exploratory study. Bus. Proc. Manag. J. 2019, 25, 250–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tardivo, G.; Thrassou, A.; Viassone, M.; Serravalle, F. Value co-creation in the beverage and food industry. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 2359–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Kenny, M.E. Connectedness to nature, personality traits and empathy from a sustainability perspective. Curr. Psychol. 2018, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A. The psychology of sustainability and sustainable development for well-being in organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Savarese, M.; Chamberlain, K.; Graffigna, G. Co-Creating Value in Sustainable and Alternative Food Networks: The Case of Community Supported Agriculture in New Zealand. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031252

Savarese M, Chamberlain K, Graffigna G. Co-Creating Value in Sustainable and Alternative Food Networks: The Case of Community Supported Agriculture in New Zealand. Sustainability. 2020; 12(3):1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031252

Chicago/Turabian StyleSavarese, Mariarosaria, Kerry Chamberlain, and Guendalina Graffigna. 2020. "Co-Creating Value in Sustainable and Alternative Food Networks: The Case of Community Supported Agriculture in New Zealand" Sustainability 12, no. 3: 1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031252

APA StyleSavarese, M., Chamberlain, K., & Graffigna, G. (2020). Co-Creating Value in Sustainable and Alternative Food Networks: The Case of Community Supported Agriculture in New Zealand. Sustainability, 12(3), 1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031252