1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship is a key element for any country aiming to be competitive in the knowledge-based global market due to the fact that it has been generally viewed as a method promoting economic growth, creativity, and innovation. This view has led to a growing interest in developing educational programmes that encourage and enhance entrepreneurship.

Although a consensus has not been reached on whether entrepreneurship can be encouraged through education, a significant amount of literature on this issue [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5] acknowledges the positive contribution of entrepreneurship education on the development of people’s know-how, skills, as well as on the enhancement of entrepreneurial attitude and intention.

As for the integration of entrepreneurship education into higher education, studies [

6,

7] stress its importance, so that 21st century universities can become important engines of technological development and economic growth.

Inclusion into academic programmes of specific disciplines dealing with company creation [

8], creation of self-employment support units and university seedbed development, or creativity and entrepreneurship workshops are a few examples of initiatives developed within universities aimed to encourage students to create companies [

5]. Moreover, educational institutions make yearly efforts to provide students with entrepreneurial role models in the classrooms [

9].

In Romania, starting in 2002, the Ministry of Education and Research, mostly due to the pressure of international programmes, introduced the discipline Entrepreneurial Education into secondary education curricula, and later, in 2013, into higher education programmes when the EU adopted the 2020 Entrepreneurship Action Plan [

10], which, along with other provisions, streamlined the development of entrepreneurship education and training.

In the last years, Romanian universities have taken significant steps to integrate entrepreneurship education into academic programmes at all higher education insitutions. These measures mainly include introduction of theoretical courses on entrepreneurship into the curricula for undergraduate and graduate students, and organization of events promoting entrepreneurship. These events are aimed to create and develop a pro-entrepreneurial attitude among students and to equip them with knowledge on entrepreneurship to make them view entrepreneurship as a viable career option [

11]. Communication with the business community and student involvement in this process have been facilitated through business hub infrastructure. Student entrepreneurial associations and technology transfer centres have been set up in several Romanian universities, but there are still only a few such centres.

Even if there had been several initiatives employing different pedagogical designs for entrepreneurship education, things have started to change quite recently, and few attempts have been undertaken to assess how different teaching methods of entrepreneurship education influence the attitude towards entrepreneurship and the entrepreneurial intentions of students in Romanian universities. Even less studied is the degree to which pedagogical design of entrepreneurship education within master’s programmes has similar or different effects on different BA degree graduates. In fact, researchers identified the need of deeper investigation that directly links student/graduate entrepreneurial outcomes to different pedagogical methods [

12], as well as the need to consider how the contextual factors, such as student background in entrepreneurship education, impact research [

13].

This study fills this knowledge gap and describes a pilot experience that was carried out with graduate students enrolled in a Business Creation course in a Romanian university, with the aim to assess the influence of exposure to successful entrepreneurial models on students by taking into consideration the views of students on entrepreneurial success. This way, each participant chooses his or her own model, learning from it, but also learns from the role models chosen by their peers.

Individuals are attracted to role models they perceive as being similar to them in terms of their characteristics, behaviour or goals (role aspect), and from whom they can learn specific skills or competencies (model aspect) [

9]. Therefore, a successful entrepreneur possessing such characteristics could enable an individual to cope with the challenges and demands of the business environment. Studies report that successful entrepreneurial models can have a positive impact on both the attitudes of individuals towards entrepreneurship and on their entrepreneurial intentions [

9,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24].

Although the existence of entrepreneurial models has become a common practice, the influence of these role models on entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions of students has not been researched enough in the academic context.

The goals of our research are threefold: (i) to identify which characteristics students view as being specific to a successful entrepreneur; (ii) to establish the influence that the exposure to successful entrepreneurial role models (chosen by students) during entrepreneurship education classes has on student entrepreneurial intentions; (iii) to establish how this exposure influences the attitudes of students towards entrepreneurship.

For this purpose, we have designed several research steps. The study first presents the theoretical framework that includes a literature review of successful entrepreneur profiling and the influence of entrepreneurial role models on entrepreneurial intention and attitude towards entrepreneurship. Then, the review is used to formulate the research questions and to streamline the role of student exposure to successful entrepreneurial models in entrepreneurship education. The next section describes the research methodology (sample and data collection, research steps, used methods). Finally, we discuss the main results concerning student perceptions of successful entrepreneur profiles, and present our findings on how student perceptions of entrepreneurship have changed due to their exposure to successful entrepreneurial models.

4. Results

4.1. Student Perception of Successful Entrepreneur Profile and Behaviour

Based on the content analysis of the students’ initial essays and the information they provided on entrepreneurs in their records, we identified a set of features of successful entrepreneurs.

These features are shown in

Table 3.

Generally, students mentioned the following qualities and common values of successful entrepreneurs: perseverance, altruism, responsibility, morality and common sense, ‘… is correct, with very well defined principles, has morality, he is sincere and transparent and … he helps you to believe that all good things happen. He is always open-minded to learn new things’ (S4 says about M4).

Some participants appreciated the creativity and innovation of a successful entrepreneur as he ‘… revolutionized technology, wanting to do things differently’ (S22 about M22) and others noted the focus of entrepreneurs on current global issues: ‘is a leader, attentive to current global issues, aiming to improve people’s lives’ (S7 about M7), ‘is a responsible entrepreneur, meant to help humanity’ (S11 about M11). Other students noticed that their entrepreneurial role models showed a great entrepreneurial spirit, for instance, giving up on a successful career in the political field to put their skills into practice (S21 about M21), or a good work–life balance as they ‘managed to successfully combine their personal and professional life’ (S28 about M28).

Another element, through which we shaped the profile of successful entrepreneurs, was the entrepreneurial behaviour. In this study, it is analysed in terms of the following aspects: the source of the business idea, the reason for entering the business environment, and the source of funding.

(a) The Source of Business Idea

Sasu [

97] groups the sources of business ideas into categories that reflect either the macroeconomic trends (demographic, social, technological, and business), or the microeconomic context. Based on the analysis of entrepreneur files filled-in by students, frequently encountered sources of business ideas for the chosen entrepreneurial role models were:

Previous job (M1, M6).

Opportunities (M2, M13, M14, M17, M19, M21, M23, M25).

Passions and hobbies (M5, M15, M18, M23, M24, M25, M28, M30): ‘Passion for agriculture and fish farming’ (M5), ‘Being passionate about sports’ (M24).

Travels: ‘traveling to Australia, identifying a new lifestyle’ (M4), ‘a spiritual journey to India’ (M22), ‘a trip to Portugal’ (M26).

Books: ‘Isaac Asimov’s books’ (M7), ‘Dale Carnegie’s book The Secrets of Success’ (M8), ‘Books read, which influenced his ideas and perception towards life’ (M11).

The family: the continuation of the family tradition in the entrepreneurial field (M3, M29), ‘The family, the skills acquired in childhood’ (M9), ‘… the idea came from my family … from my grandmother’s vegetable garden’ (M21), ‘the idea came from the family (mother), traveling abroad and having a vision’ (M16).

National traditions and culture (M30).

(b) The Reason for Entering the Business

Based on content analysis, we found that the entrepreneurial role models that students chose had the following reasons for entering the business environment:

Financial independence, family welfare (M5, M13, M14, M17, M21); ‘To help their family and parents more’ (M1), ‘financial stability for the family’ (M21), ‘Out of the need and desire not to live from one day to the next’ (M23), ‘escaping poverty and hunger helped him get into business’ (M24).

Out of desire to overcome their social status (M15, M20, M27).

From the desire to ‘change the world’: ‘entered the business to move science, technologies globally’ (M7).

For social reasons: to create jobs (M5), ‘helping others’ (M16), to promote a healthy life (M9, M12).

Based on beliefs: the model promoted by parents ‘… never depend on a single income, have more jobs’ (M10).

Desire to dedicate themselves to their passions: ‘to do what he likes’ (M4), ‘giving up the previous job and focusing on an area, where he can put his talents, passion and satisfaction into practice’ (M18), ‘He wanted his passion to become a reality, or to work for something he is passionate about’ (M11).

(c) The Source of Funding

The financing sources of the entrepreneurs chosen as models by the students were diverse and depended either on the economic, social, and political contexts of the country from which the entrepreneur came, or on the idea and the reason for entering the business.

Following the content analysis of the entrepreneur files filled-in by students, the following business sources were identified:

Money from their relatives (M1, M12, M17, M29).

Own sources: personal savings (M4, M6, M10, M15, M16, M18, M25, M28), ‘wedding money’ (M21); ‘own funds made from the sale of some goods, land’ (M22), ‘little savings and free Internet resources’ (M23), the money obtained from previous activities (M24).

European funds, funding from other institutions (M2, M8, M9, M13, M14, M19, M20, M30).

Loans (M5, M16).

Previous ventures: they started the entrepreneurial activity with a small business that they sold and this was the source of funding of another business (M7, M11, M27).

4.2. Results on Student Entrepreneurial Intentions and Attitudes towards Entrepreneurship before Exposure to Successful Entrepreneurial Models

The descriptive statistics (

Table 4) calculated for the variables describing the entrepreneurial intentions of students before exposure to successful entrepreneurial models showed, for the considered sample, a high intensity in entrepreneurial intention (average scores with values between 4.37 and 4.83, and modal score 6 for variables I1, I2, I4, I5), and a low level of doubts regarding the achievement of the entrepreneurial enterprise (average score of 1.30 and modal score 0 for variable I3).

Concerning attitude towards entrepreneurship, descriptive statistics (

Table 5) showed a positive perception, students associating entrepreneurship especially with creativity and innovation (average score of 5.17 and modal score of 6, minimum score of 3), taking calculated risks (average score of 4.80 and minimum modal score of 4, minimum score of 3) and being independent/being own boss (average score of 4.77 and modal score of 6). Respondents largely associated entrepreneurship with facing new challenges, creating new jobs for other people and generating high income, all statements having average scores higher than 4.

4.3. Assessment of Entrepreneurship Attitudes and Entrepreneurial Intentions of Students after Exposure to Successful Entrepreneurial Models

The descriptive statistical indicators (

Table 6) calculated for the variables describing entrepreneurial intentions of students after exposure to successful entrepreneurial models showed a higher average intensity of the entrepreneurial intention (higher average scores, with values between 4.93 and 5.10, for variables I1, I2, I4, I5), and an equally low average level of doubts towards developing an entrepreneurial enterprise (average score of 1.30 for variable I3). The most important growth (of 0.30 points) was noted for the variable ‘I am willing to make all the necessary efforts to become an entrepreneur’.

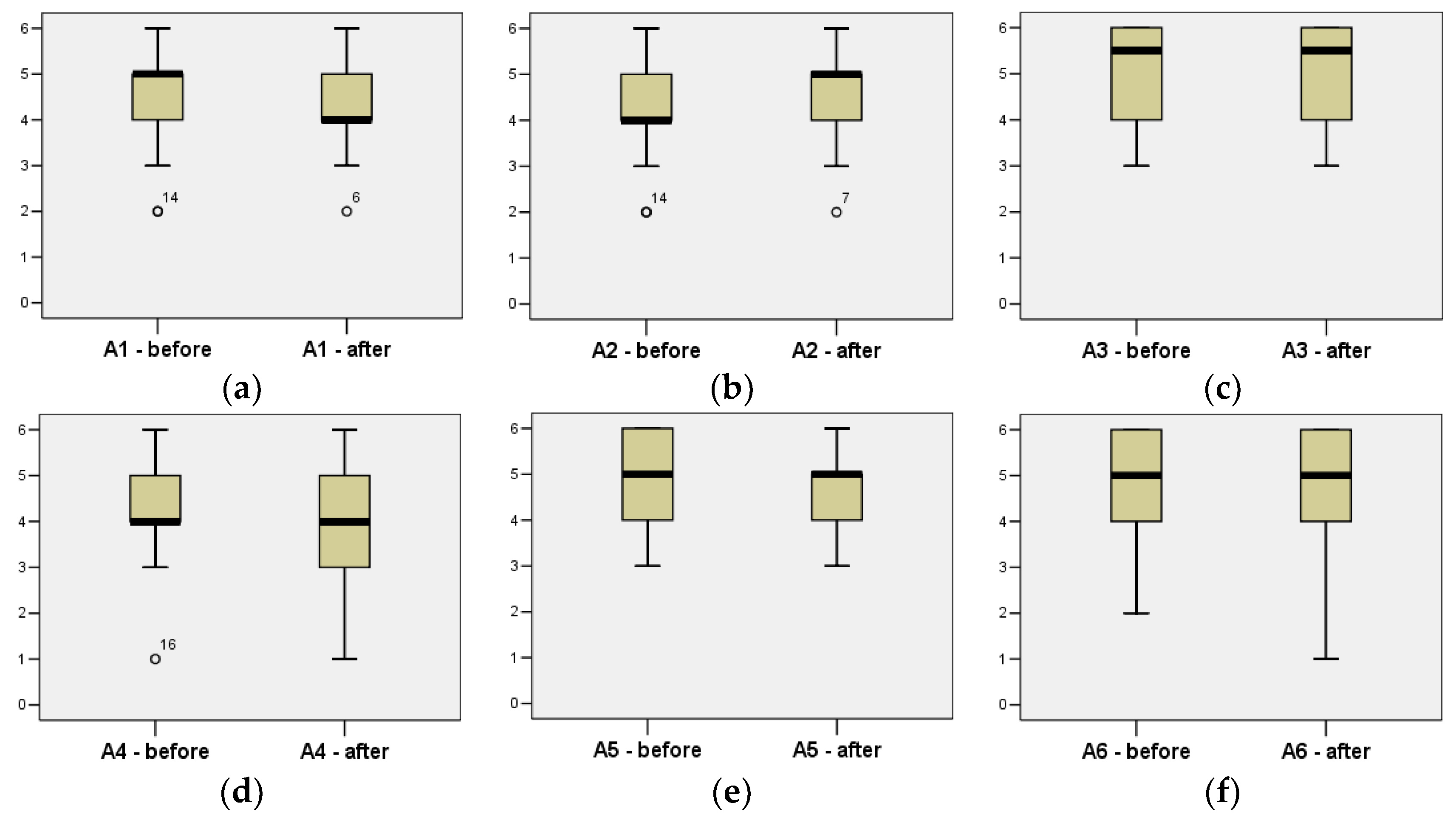

Analysis of box-plot diagrams of the values for the variables describing entrepreneurial intention at the two time points (before and after exposure) (

Figure 1) showed a similar form of the diagrams for high values and a reduced length of the diagram for lower values (for variables I1, I2, I4, I5). This fact could be interpreted as follows: students with medium and high levels of entrepreneurial intention maintained their intensity of intention, while those who did not consider entrepreneurship as an occupational option were willing, after exposure to entrepreneurial models, to take it into consideration. In the case of variable I3, which expresses the level of doubt regarding the development of an entrepreneurial enterprise, the forms of the two diagrams were similar.

Table 7 presents distributions of the values of Difference variables for the statements describing entrepreneurial intention. These values were determined as differences between the scores awarded by students after and before their exposure to successful entrepreneurial models.

‘It is very likely that one day I will start my own business’: The distribution of respondents by their perceptions of the likelihood of starting a business showed that, after exposure to successful entrepreneurial models, 5 students (16.7%) were less willing to start a business (difference equal to −1), 19 (63.3%) were equally willing, their intention being unchanged (difference equal to 0), while for 6 (20.0%) of the 30 respondents, the intensity of the intention to set up a business increased.

‘I am willing to make every effort to become an entrepreneur’: After being exposed to successful entrepreneurial models, 6 students (20.0%) were less willing to make an effort to become an entrepreneur (the difference equal to −2 or −1), 14 students (46.7%) were equally willing, their intention being unchanged (difference equal to 0), and for 9 of the 30 respondents (33.3%), the intensity of the intention to make high efforts to become an entrepreneur increased.

Regarding the statement ‘I have serious doubts that one day I will get to create a company’, after exposure to successful entrepreneurial models, 8 students (26.6%) experienced a higher level of doubt that they will create an enterprise one day, for 11 students (36.7%) the level of doubt remained unchanged, while for the remaining 11 students (36.7%), it decreased.

‘I am determined to create a business in the future’: After exposure to successful entrepreneurial models, 7 students (23.3%) were less determined to create a business in the future, 15 students (50.0%) were sure, their intention being unchanged (difference equal to 0), while, for 8 of the 30 respondents (26.7%), the intensity of the decision to set up an enterprise in the future increased.

‘My professional goal is to become an entrepreneur’: Following the exposure to successful entrepreneurial models, 8 students (26.7%) agreed to a lesser degree that their professional goal was to become an entrepreneur, 12 students (40%) had the same intensity of intention to consider entrepreneurship as a professional goal, while 10 students (33.3%) had a higher degree of agreement in relation to establishing entrepreneurship as a professional goal.

The box-plot diagrams showed changes in entrepreneurial intention, especially for the lower scores, namely, an improvement in intention after exposure to successful entrepreneurial models in the cases of students less interested or not interested in entrepreneurship.

Concerning attitude towards entrepreneurship, the descriptive statistics showed that the positive perception was maintained after exposure to successful entrepreneurial models, too. In the final stage of the study (

Table 8),

Creativity and innovation (average score of 5.13),

Being independent/being own boss (average score of 4.90) and

Taking calculated risks (average score of 4.50) were still the main elements with which students tended to associate entrepreneurship. There was an increase in the average scores for the association of entrepreneurship with

Being independent/being own boss and with

Creating new jobs for other people, while for the other statements there were slightly lower average scores. The most important change in the perception of entrepreneurship was observed in its association with

High income (decrease of the average score from 4.30 to 3.90).

The analysis of the box-plot diagrams of the values for the variables describing attitude towards entrepreneurship obtained in the two time points considered in the analysis (

Figure 2) showed the following:

a similar form of the diagrams for the Creativity and innovation variable;

similar forms of the diagrams, but with slight changes in the concentration of the scores for the variables: Confronting with new challenges (a lower median score), Creating new jobs for other people (a higher median score), Assuming calculated risks (lower number of maximum scores) and Being independent/being your own boss;

an extension of the chart to lower scores for the High income variable.

The results confirmed the high degree to which students associated entrepreneurship with Creativity and innovation, as well as with an occupation allowing them to maintain their independence. At the same time, after the exposure to successful entrepreneurial models, we noticed a greater orientation of the students’ perceptions towards the social benefits of entrepreneurship (Creating new jobs for other people) in comparison to financial ones (High income).

Table 9 presents the distributions of values for the

Difference variables, matching statements describing attitude towards entrepreneurship. These values were determined as differences between the scores given by students after and before exposure to successful entrepreneurial models.

Facing new challenges: After exposure to successful entrepreneurial models, 15 students (46.7%) associated entrepreneurship with new challenges to a lesser extent, 7 students (23.3%) had an unchanged attitude (difference equal to 0), while 9 of the 30 respondents (30.0%), agreed to a greater extent that entrepreneurship involved facing new challenges.

Creating new jobs for other people: Following exposure to successful entrepreneurial models, 9 students (30.0%) to a lesser extent associated entrepreneurship with the creation of new jobs for other people, 10 students (33.3%) had an unchanged attitude, and 11 of the respondents (36.7%), agreed to a greater extent that entrepreneurship meant creating new jobs for other people.

Creativity and innovation: The attitudes of most students, 21 (70.0%), remained unchanged after exposure to successful entrepreneurial models, 4 students (13.3%) to a lesser extent associated creativity and innovation with entrepreneurship, while 5 respondents (16.7%) associated the two phenomena to a greater extent.

High income: After exposure to successful entrepreneurial models, 15 students (50.0%) maintained the same attitude towards associating entrepreneurship with high income, 12 students agreed less (40.0%) with this association, only 3 respondents (10.0%) claimed more strongly that entrepreneurship involves high income.

Assumption of calculated risks: Following the exposure to successful entrepreneurial models, 14 students (46.7%) agreed to a lesser extent that entrepreneurship involved assuming calculated risks, 9 students (30.0%) had the same attitude, while, for 7 of the 30 respondents (23.3%), the values of the scores given to the association between entrepreneurship and the calculated risk-taking increased.

Being independent/being your own boss: Following exposure to successful entrepreneurial models, most students, 13 (43.3%), associated entrepreneurship to a greater extent with an occupation allowing being independent or being your own boss, 10 students (33.3%) maintained the same attitude, while 7 respondents (23.3%) agreed to a lesser extent that entrepreneurship implied being independent.

4.4. Student Perceptions of the Influence on Their Entrepreneurial Intentions Due to Exposure to Successful Entrepreneurial Models

Content analysis of the mini-essays written by students on their perceptions of the ways in which their entrepreneurial intentions and attitudes towards entrepreneurship have been influenced by their exposure to successful entrepreneurial models showed that:

A high entrepreneurial intention existed before the applied experimental session. After the exposure to successful entrepreneurial models, students felt they gained more confidence in implementing their business ideas and strengthened their desires to become an entrepreneur:

‘I have to dare and believe that my business idea will work and it will be successful’ (S4).

‘Due to the success stories presented, the students gained more confidence in starting a business’ (S5).

‘The presentations made me become more optimistic and confident’ (S11).

‘Exposure to successful models has aroused my interest in getting into business at one point, they have given me the urge to follow my desire to do what I want’ (S15).

‘The models gave me the courage to do what I want and not to be influenced by others who only speak and do nothing. … I want to set up my own company!’ (S16).

For non-business students, the positive influence of exposure to successful entrepreneurial models was more visible because, besides feeling more confident about their entrepreneurial skills and feeling a greater self-efficacy, they mentioned that the experience of being exposed to successful entrepreneurial role models brought them a better understanding of entrepreneurship and awakened or increased their interest in becoming an entrepreneur.

‘It made me learn more from the experience of other entrepreneurs to better understand the challenges of this job’ (S1—Law).

‘It has helped me to really discover entrepreneurship and that, having your own business is not difficult, but keeping your business and making it prosper is difficult. It is important how you make the decisions, I learned how to behave in a team and with clients’ (S3—Food Engineering).

‘You must never give up your ideas, but improve them and adapt them according to specific opportunities or situations’ (S8—Philology).

‘Even though I had some ideas about entrepreneurship, I didn’t think I was suitable for being an entrepreneur, but due to exposure to successful models I learned that if you have a well-defined idea and you work hard enough you can set up a successful business’ (S9—Philology).

‘Each of us had something to learn from the successful models of entrepreneurs and I understood how much work and perseverance a successful business requires. It has created in my mind a certain entrepreneurial discipline that I did not have before and also built my own confidence’ (S12—Pedagogy).

‘There were very interesting success stories, and our entrepreneurial intentions were influenced by the entrepreneur’s personality, his qualities and the way he acted. There have been cases of entrepreneurs who … from being nobody became somebody. How can you not be influenced and motivated by such a situation?!’ (S14—Psychology).

‘Attending this course has grown my interest to set up a family business. This type of business creates a sense of security, especially when there are harmonious relationships within the family’ (S19—Theology).

‘Exposure to a successful entrepreneurial model had the role of developing my entrepreneurial spirit. Each success story grew in us an entrepreneurial spirit’ (S23—Architecture).

‘Success stories have grown my interest in becoming an entrepreneur’ (S24—Physical education).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Nowadays the economic and social changes in society show the importance of developing entrepreneurship and creativity skills [

98,

99,

100]. The universities, as mentors, and the successful entrepreneurs, as role models for students, can play an important role in the entrepreneurial education of the young and in enhancing their entrepreneurial spirit. From this perspective our study investigated the role of successful entrepreneurial role models in influencing the entrepreneurial intentions of students and their attitudes towards entrepreneurship.

The analysis of descriptions provided by students showed that they describe successful entrepreneurs using characteristics similar to those reported in the literature, such as creativity [

30,

34] and risk-taking [

30,

31,

34]. Most students identified the following characteristics for defining successful entrepreneurs: perseverance (8 of 30 respondents), orientation to people and desire to help others (7 of 30 respondents), and entrepreneurial spirit (5 of 30 respondents). The perseverance feature is in line with the characteristic of

increased capacity for intense and lasting effort found by Nastase [

31].

Orientation to people and

desire to help others confirm the characteristic of

orientation towards human capital identified by Amornpinyo [

32]. The

entrepreneurial spirit feature was also found by Snepar [

34], who describes the entrepreneur as a person

following an unconventional or unpopular approach to solving a problem.

By studying the entrepreneurial behaviour of successful role models, students learned about sources of business ideas, contexts and reasons for starting a business, and the main funding sources. The characteristics of entrepreneurial behaviour of successful entrepreneurs may represent a source of inspiration and motivation for students to become entrepreneurs themselves.

The analysis of how exposure to successful entrepreneurial models influences student perceptions of entrepreneurship provided evidence on the following issues.

Descriptive statistics of student entrepreneurial intentions before and after exposure to successful entrepreneurial models indicate changes in intention, in both a positive and a negative sense.

The graphical analysis reflects changes in entrepreneurial intention, especially in the area of lower scores, indicating an improvement in intention after exposure to successful entrepreneurial models for students less interested or not interested in entrepreneurship.

In regards to the attitude towards entrepreneurship, descriptive statistical values show a positive perception both before and after exposure to successful entrepreneurial models. In the final stage of the study, we observed that such characteristics of attitude towards entrepreneurship as creativity and innovation, being independent/being your own boss and taking calculated risks were still the main elements the students tended to associate with entrepreneurship. In contrast, there was an increase in average scores for the association of entrepreneurship with being independent/being their own boss and creating new jobs for other people, while for the other statements there were slightly lower average scores. The most important change in the perception of entrepreneurship was observed in its association with high income. So, after exposure to successful entrepreneurial models, we were able to observe a greater orientation of student perceptions towards the social benefits of entrepreneurship (creating new jobs) rather than to financial ones (high income), proving that students have become more aware of this dimension of entrepreneurship.

Our results show that exposing students to success stories of entrepreneurs, viewed by students as role models, is a key influence factor in making the decision to start a business, contributing to the improvement of entrepreneurial intention of less interested or not interested students in entrepreneurship.

In line with previous studies, such as Martin, McNally, and Kay [

72], Wilson, Kickul, and Marlino [

76] or Zhao, Seibert, and Hills [

65], our findings of content analysis and graphical distributions of student perceptions show that learning entrepreneurship by exposure to successful entrepreneurial role models is important in influencing student entrepreneurial intentions and in improving their attitudes towards entrepreneurship. However, the impact of this teaching method is different for graduate business and non-business students (such as literature, architecture, agronomic sciences, psychology, pedagogy, theology, sports, and law).

For the first category of students, entrepreneurial intention might have been high right from the start of the course, as they had already studied many concepts related to business environment that made them more open to entrepreneurship. For these students, the most important consequence of learning from successful entrepreneurship stories may reside in the fact that they felt they had gained more confidence in implementing their business ideas and strengthened their desire to become entrepreneurs. This consequence was observed for many of the students who comprised the sample, irrespective of their degree.

Our results are in line with the study of Karimi, Biemans, Lans, Chizari, Mulder, and Mahdei [

56] which suggest that including contact with entrepreneurial models as part of the entrepreneurship education curriculum can stimulate students’ confidence in their ability to start a business and improve their attitude towards entrepreneurship. The findings of our study also support the approach of Byabashaija and Katono [

86], who suggest that using case studies of local entrepreneurs in teaching entrepreneurship can be instructive regarding the feasibility of entrepreneurship as a career option.

The results of our study provide evidence for the theoretical perspective of entrepreneurial self-efficacy [

68], which argues that entrepreneurship education is associated with entrepreneurial self-efficacy that can enhance entrepreneurial intentions [

65,

76]. Role models, in particular, can stimulate individual self-efficacy by providing vicarious experiences to students and by increasing positive emotional reactions to entrepreneurship [

56].

As regards non-business students, the positive influence of exposure to successful entrepreneurial models is more visible because, besides feeling more confident in their entrepreneurial capacities and feeling a greater self-efficacy, they mentioned that the experience of being exposed to successful entrepreneurial role models brought them a better understanding of entrepreneurship and awakened or stirred their interest in becoming an entrepreneur.

These findings are in line with those of Bygrave [

16], who found that knowing successful entrepreneurs makes the act of becoming one oneself seem more credible, and with the findings of Lafuente, Rialp, and Vaillant [

23], who underline that contact with an entrepreneurial role model makes people more inclined towards developing a desire and confidence to create their own businesses. Our findings bring support to the human capital theory [

67], a theoretical perspective arguing that entrepreneurship education is positively correlated with entrepreneurial intentions.

Our study provides evidence that entrepreneurship education using successful entrepreneurial role models may influence in a positive sense student entrepreneurial intentions and their attitudes towards entrepreneurship and is in agreement with Hatten and Ruhland [

101], who found that students were more likely to become entrepreneurs after attending an entrepreneurship-related programme.

However, our findings show that in order to make this educational method more efficient, entrepreneurship education programmes for master’s degrees should be designed differently for business and non-business students. This need emerges from the fact that studying successful entrepreneurial stories impacts the two categories of students differently. This conclusion complies with Teixeira’s [

102] recommendation that if a goal in designing entrepreneurial programmes is to assist students within and outside the business school, it is important to understand the similarities and differences between business school students and their non-business counterparts.

Our findings also support what Urbano et al. [

88] suggest: that courses and curricula of entrepreneurship should be designed so as to take into account the students’ profiles.

Although the idea of exploring role models as antecedents of student entrepreneurial intentions is not new, our research adds to the existing literature by considering individuals’ (students’) own perceptions of entrepreneurial success and their preferences for the chosen role models (the ones they identify with or whom they admire).

This could be a valuable approach for entrepreneurship education as it incorporates higher involvement and participation of students, while exposing them to different perspectives of entrepreneurial success. This way students acquire more knowledge on entrepreneurship by becoming more accustomed with various contexts in which individuals become entrepreneurs, learning about the main sources for business ideas, discovering various business ideas and specific methods for their implementation, and finding out about various methods for dealing with different obstacles that could appear in their entrepreneurial experience.

Limitations and Future Research

Considering our results and the characteristics of the student sample, we should point out the limitations of the study: first, the sample size comprised only 30 students; second, sample composition favoured the students having a business degree; and third, the statistical analysis treated all sample students equally, although they had different undergraduate degrees.

Integrating exposure to successful entrepreneurial models into entrepreneurship education programmes for students can be a teaching–learning method with potential from the perspective of sustainable development education as it develops students’ entrepreneurial capacities, increases their entrepreneurial intentions and willingness to set up a business.

In order to improve entrepreneurship education as a driver to foster sustainable entrepreneurship among students, more research should be done to identify the appropriate teaching methods for different groups of students. Future studies should use an extended sample and compare various methods for teaching entrepreneurship to students from different study areas. The outcomes of entrepreneurship education might be different when different teaching methods that employ entrepreneurial role models are used (for instance, learning from failure, not only from successful entrepreneurial stories; learning by doing; or learning through support), so this should be further investigated in a future study.