Abstract

When people evaluate the environmental impact of both “environmentally” and “non-environmentally” friendly objects, actions, or behavior, their judgement of the total set in combination is lower than the sum of the individual components. The current communication is a personal perspective article that proposes a human cognitive framework that is adopted during evaluations, which consequently results in wrong reasoning and the reinforcement of misconceptions. The framework gives plausible interpretation of the following: (1) “compensatory green beliefs”—the belief that environmentally harmful behavior can be compensated for by friendly actions; (2) the “negative footprint illusion”—the belief that introducing environmentally friendly objects to a set of conventional objects (e.g., energy efficient products or measures) will reduce the environmental impact of the total set; and (3) “rebound effects”—sustainability interventions increase unsustainable behavior directly or indirectly. In this regard, the framework herein proposes that many seemingly different environmentally harmful behaviors may sprout from a common cause, known as the averaging bias. This may have implications for the success of sustainability interventions, or how people are influenced by the marketing of “environmentally friendly” measures or products and policymaking.

1. Introduction

Climate change is one of society’s grand challenges [1,2] and clearly the global efforts to meet the target of the 2015 Paris climate agreement will be difficult unless public and political opinions reinforce necessary national and international regulations of greenhouse gas emissions. Society now places large quantities of both time and money to focus on developing technological solutions to fight climate change or build a more sustainable society. This observation is also reflected in current trends in research funding. In modern society, energy-efficient technologies are marketed as having one of the biggest implications on reducing energy use and consequently emissions. However, in as much as advances in energy-efficient products naturally reduce emissions, through reduced energy demand, people’s response to how they use the products (people’s behavior) can offset the benefits through what is commonly known as the rebound effect (or take-back effect). Conservation and energy economists describe the rebound effect as the reduction in expected gains from new technological improvements and increased efficiency of resource use due to users’ behavioral or other systemic responses [3,4]. These responses usually offset the benefits of the new technology or other sustainability measures. To illustrate, when fuel-efficient cars are introduced on the market, it is logical to assume that without any change in driving patterns and behavior, there should be a drop in the amount of fuel use. On the contrary, fuel use remains the same and, in some cases, increases because with fuel-efficient cars people start to drive more, faster, and/or over long distances [5]. While the existence of the rebound effect is widely accepted, there is no agreement (even in the scientific community) on what really causes people to change their behavior, although some mitigation measures have been proposed [6].

Another issue that hampers progress to impede climate change is public acceptability of environmental policies, which can be achieved in various ways. One way is to use nudging—positive reinforcement and indirect suggestions as ways to influence the behavior and decision-making of groups or individuals [7]. Nudging has been criticized for its ethical and practical issues, for being manipulative, patronizing, undemocratic, and culturally biased, among other things [7,8]. Another way is to achieve public participation in pro-environmental behavior by use of affordances—relationships that define possible uses of an object or make clear how it can or should be used [9]. Affordances couple internal factors (attitudes and knowledge) and the external factor (environment) as an enabling dynamic system for pro-environmental behavior [10,11]. Nudging and affordances are external forces that can facilitate sustainable behavior, but the public’s willingness to accept policies and support them in overt behavior depends on many factors [12], although it is mostly driven by internal factors [13]. These internal factors include, but are not limited to, values and beliefs in human–nature relationships [14,15,16] and, according to Gifford [17], “limited cognition about the problem, ideological world views that tend to preclude pro-environmental attitudes and behavior, comparisons with key other people, sunk costs and behavioral momentum, discredence toward experts and authorities, perceived risks of change, and positive but inadequate behavior change.”

This paper proposes a new framework of the cognitive underpinnings of environmentally related human behavior. The framework, a cognitive abstraction of thought processes employed when making evaluations, suggests that many environmentally harmful behaviors, which may look different on the surface, may all be underpinned by a common mechanism. This mechanism may provide a plausible explanation of why people change their behavior after the introduction of energy efficiency measures and how this information can be used to market and label energy efficiency measures and technologies as well as environmental policies that may countervail rebounds.

2. A Cognitive Framework of Evaluating Environmentally Related Objects or Behavior

People’s thinking and reasoning about climate change is biased and inaccurate in systematic ways [18]. Therefore, environmentally harmful behaviors often have their roots in cognitive biases and cognitive inabilities to understand the environmental impact, the effects of one’s own behavior on the environment, and other means by which thinking and reasoning are biased [19].

Cognitive bias is defined in this paper as a mistake in reasoning, or evaluating a problem, (i.e., climate change) because of limited cognitive capacity to process information even when the problem is understood. Herein, the definition makes a generalization without considering personal or individual preferences and beliefs. The mistake in reasoning is because the human brain adopts information-processing heuristics that tend to classify information based on dichotomies [20], therefore attaching symbolic values rather than actual attributes to objects or behavior. Such heuristics are hard-wired tools in the brain, which makes information processing efficient, pragmatically successful, and inexpensive. At the same time, when the brain is confronted with a task that it is not well adapted to, these heuristics can result in erroneous thinking [21,22], mostly because the adopted heuristic leaves out valuable information, even when it is provided. As discussed herein, perhaps understanding climate change and the environmental impact of one’s own behavior may be an example of tasks to which the brain is not well adapted

Cognitive inabilities to understand the underlying mechanism of climate change promote cognitive misconceptions which may spill over through change of behavior causing rebound effects. To illustrate, people struggle to understand the stock–flow relationships governing carbon dioxide (CO2) accumulation in the atmosphere [23]. This is an example of the internal factor—“limited cognition about the problem” [17]. Understanding global warming requires an understanding of dynamic systems, that is, how the inflow and outflow of greenhouse gases interact via natural absorption and how these dynamic processes determine their concentrations in the atmosphere. One aspect people struggle to understand, even highly educated ones, is the systems’ response delay; for example, CO2 accumulation increases even if emission cuts are made, only to stabilize when emissions equal atmospheric depletion or removal [24]. This is to say that trends of CO2 accumulation are hard to notice over a short period (e.g., a year or even a decade) but appear when extrapolated over a long period. It has been shown that people’s understanding of CO2 accumulation can be improved with analogies [25] but often without much success [23]. It should be noted in this paper that cognitive inability to understand the problem is outside the focus of this communication.

2.1. Cognitive Misconceptions and Biases When Making Evaluations

One of the cognitive misconceptions is that environmentally friendlier objects are “good” for the environment rather than “less bad” for the environment—the “green is good”: misconception [26]. Another misconception is that environmentally friendly actions can compensate for more harmful actions—the “green compensation” misconception [27]. The latter is grounded in social interactions as we have evolved to think we can balance good and bad social behavior, yet we seem to apply the same logic to how we interact with the environment [28]. Sadly, the green compensation misconception is being reinforced with an increase in campaigns such as climate compensation, that is, pay extra for climate-compensated flights, eating beef in “100% climate-compensated” restaurants [29], and sustainable fast fashion which encourages customers to return old used clothes in exchange for shopping vouchers or discounts (encouraging more shopping), when retailers should instead encourage customers to buy fewer clothes considering the large environmental burden of the textile industry and how little recycled clothes contribute to new production [30,31].

These misconceptions have been shown in people’s evaluation of environmentally related objects. Gorissen and Weijters [32] asked participants in a study to estimate the environmental impact either of a hamburger alone or of a hamburger in combination with an eco-friendly side dish. The participants assigned a lower environmental impact value to the hamburger with the eco-friendly side dish. The observed effect was named “the negative footprint illusion”, whereby the addition of objects deemed “environmentally friendly” (the side dish in this case) makes people believe that the environmental impact is reduced (although the environmental impact of the sum of the two objects is larger than that of the single item).

Holmgren et al. [26] was able to show empirically why people make this mistake. Participants were asked to estimate the carbon footprint of a set of buildings across three conditions—a condition with 15 conventional buildings, a condition with 15 “green” buildings, and a condition with a combination of both 15 conventional and 15 “green” buildings. The environmental impact estimate of the condition with 30 buildings was lower than that of 15 conventional buildings and higher than that of 15 “green” buildings. The fact that estimates of the environmental impact of the 15 conventional plus the 15 green buildings fell between the other two conditions suggests that the environmental impact estimate is based on the average between conventional and “green” items in the set.

The same bias was observed when assessing people’s understanding and beliefs concerning how periods of small emission cuts contribute to the total CO2 concentration in the atmosphere. In the study [33], participants were asked to rate the atmospheric CO2 concentration for various time periods and emission rates, of which some periods were distinguished by the introduction or use of energy-efficient technology consequently having lower CO2 emission rates. The participants judged time periods with higher emission rates combined with a period of lower emission rates to contribute less atmospheric CO2 in total, compared to the period with high emission rates alone. The estimates appeared to be based on the average rather than on the accumulated sum. Moreover, the effect was robust for words such as “environmentally friendly measures”, and when these words were dropped in the problem definition, the results showed a tendency towards an averaging bias but it was statistically insignificant. The study suggests that the averaging bias may make people exaggerate the benefits of policies or acts that push for small emission cuts and that the framing of policies or environmental measures may be an enabler to this erroneous thinking. The danger here is that the effectiveness of sustainability measures or policies or behavior that has very little impact on mitigating climate change can be overestimated and easily be accepted as solutions by the public. Additionally, how policies or sustainability measures are marketed influences how the public perceives the effectiveness of these measures.

One would think that people who are susceptible to the averaging bias lack the necessary knowledge or skills for environmental evaluation or impact assessments, consequently failing to understand the impact of their own behavior. A recent study [34] addressed this hypothesis by recruiting final year graduate students in energy systems who had knowledge of building energy systems and environmental assessments as these are extensively covered in their study program. The students were presented with two sets of buildings, each with an image typically used to present details of energy efficiency of buildings. One set had 150 buildings of the same type and with a given energy rating, whereas another set had the same 150 buildings but with an additional 50 “green buildings” with a better energy efficiency rating. Participants were asked to estimate the number of trees needed to compensate for the environmental burden of each set of building stocks due to their total energy use. The “experts” reported that the building stock with a combination of 150 conventional and 50 “green” buildings needed less trees compared to the set with only 150 conventional buildings, manifesting an averaging bias. The reported results implied that by introducing buildings with a much higher energy efficiency, participants assumed that these buildings were somehow offsetting the burden of conventional buildings, consequently reducing the total environmental burden of a suburb or building stock. When compared against students in social sciences with no academic training in energy-related fields, the bias was as large in magnitude for energy system students as it was for social science students. The results reveal that people with training or perhaps expertise knowledge may not be immune to the averaging bias, even when they have information necessary to make accurate judgments.

These studies show that when “environmentally friendly” items are added to a set of “regular” items, people’s evaluation of the environmental impact of the combined set decreases because they adopt a mental averaging heuristic. They mentally assess the average of the environmentally friendly and less friendly members of the set, failing to take into account that, in this case, A plus B must necessarily be larger than or equal to A (here A and B refer to non-environmentally and environmentally friendly actions or objects, respectively). In principle, if B is negative, A plus B will always be smaller than A. This, however, is not how the environmental burden due to human actions works, because all actions/products always has a positive value that adds to increased consumption or emissions from/into the environment rather than removing from it, unless it is a system that directly captures or removes greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. Therefore, a set consisting of environmentally harmful and pro-environmental attributes will each have positive values reflecting a degree of emissions added to the atmosphere, A plus B should always be bigger than A or B. So, why do people average instead of summing up?

2.2. Cognitive Abstraction of Thought Processes When Making Evaluations

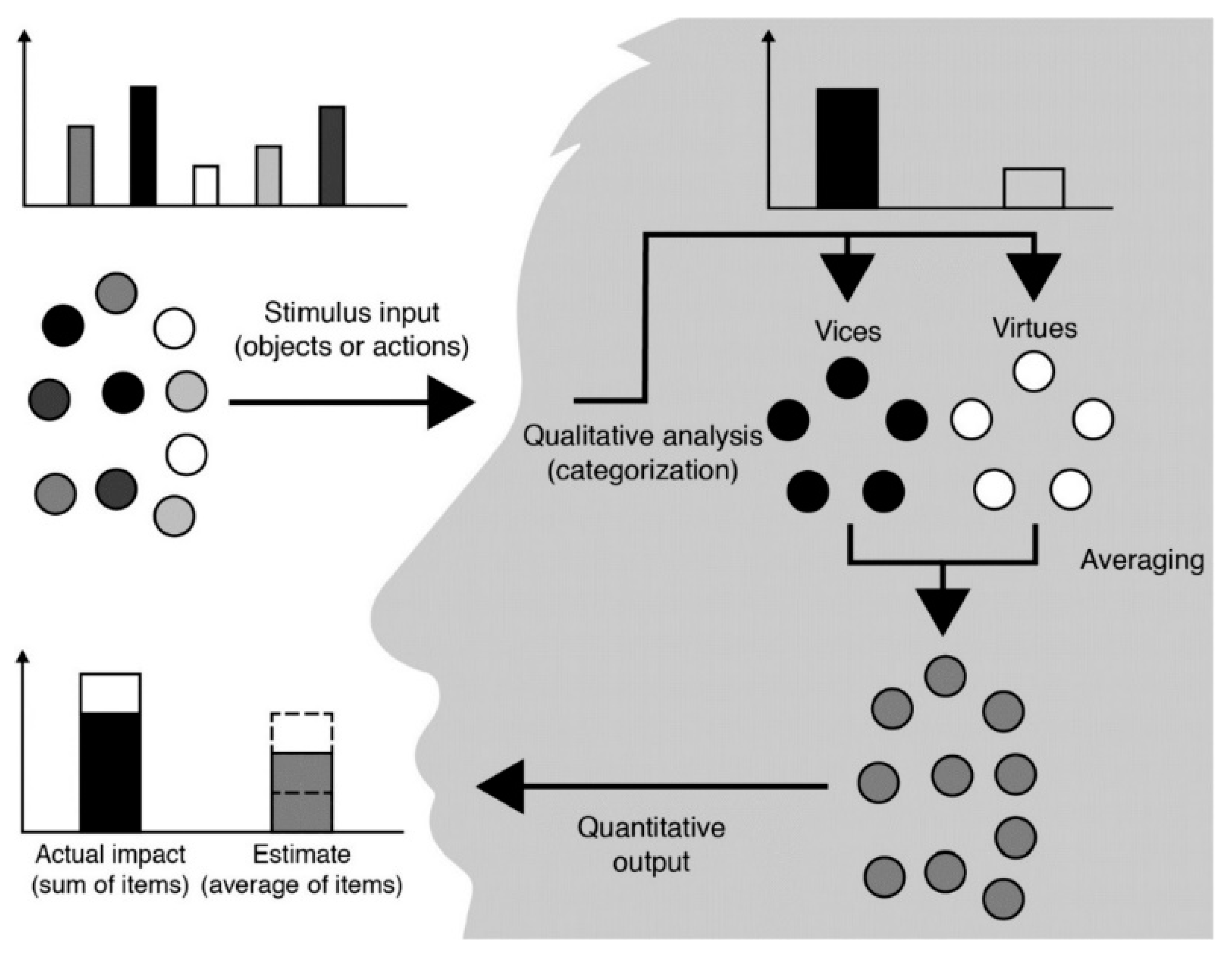

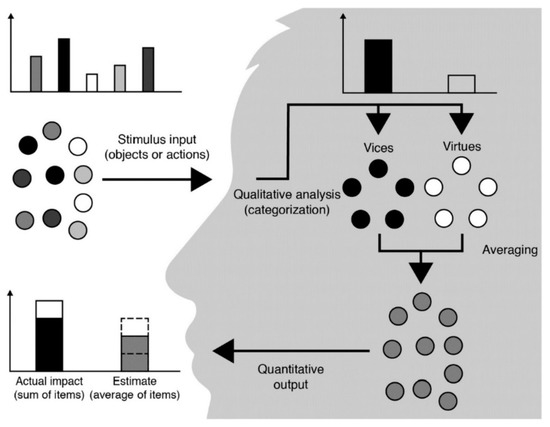

This section proposes a cognitive framework, “a cognitive abstraction of thought processes employed when making environmentally related evaluations of objects or behavior”. The framework suggests that misconception and biases come about due to the adopted information-processing heuristic during evaluations. Figure 1 illustrates the framework of the adopted information processing heuristic. When a person is asked to make an evaluation or to estimate the environmental impact of objects or their own or other people’s behavior, they produce an output based on the total set (i.e., combined environmental impact of environmentally and non-environmentally friendly objects or behavior). The thought process chain begins with stimulus input related to the question, which can be external objects in the surrounding environment or internal thoughts or memories. Here, the human brain analyzes the stimulus input’s qualities and classifies them based on dichotomies, such as “good” versus “bad”, “friend” or “foe”, “environmentally friendly” or “harmful”, “us” or “them”, “virtues” or “vices” [20]. The brain then assesses the resources at its disposal to solve this task, and one of them is the averaging heuristic which is efficient and inexpensive. Thus, it applies the mental averaging information-processing heuristic to prepare the quantitative output—the environmental impact estimate. As a result, the output of this information-processing chain is the average of the items in the combined set (environmentally friendly and harmful objects) but not the sum of the items.

Figure 1.

Framework of the processes underpinning averaging bias; figure reproduced from [33].

The problem that people face here is categorization, similar to the problem concerning the environmental impact of objects in Holmgren et al. [26,34]. When assessing the environmental impact of a set of environmentally friendly actions or behavior, the proposed framework suggests that people tend to overlook the quantitative details even when such is provided, but rather categorize attributes qualitatively and thus end up with an average of these objects or actions rather than the sum. By averaging, when people add the believed benefits of sustainability interventions and/or technological inventions to their self-view, they believe the environmental impact decreases. Therefore, the impact of environmentally friendly measures on the overall set ends up being overestimated. Consequently, people take many environmentally harmful actions with the view that these are being compensated for through some actions that they deem environmentally friendly. On the other hand, people may tend to overuse sustainable technological interventions while still believing that, overall, they are doing something good for the environment. The averaging bias, hence, could be the reason why people think they can act or do something to compensate for environmentally harmful behavior—compensatory green beliefs [27].

An example, on the micro level, is when people in a grocery store add another set of “eco-friendly” fruit and vegetables to their basket with the purpose of reducing the environmental impact of the contents (beef or dairy products) of the basket, whereas the best way would be to instead remove items from the basket. Another example, on a grander macro level, are the decisions concerning how to create sustainable megacities for millions of people in the face of global population growth. From a sustainability perspective, the best thing to do is to provide living conditions and cultures that over time reduce consumerist behavior and, arguably, limit global population growth. In other words, the best solution is to reduce the source of the negative environmental impact (the contents of the basket) and simplify lifestyles to reduce the environmental burden of providing for a large population. Instead, people act to compensate for the source (buying more “eco-friendly” groceries or other products and building costly “environmentally friendlier” infrastructures, etc.).

Another form of environmentally harmful behavior are those related to rebound effects on energy efficiency or emission reduction measures. Rebound effects can take many forms, but researchers distinguish direct and indirect effects [35]. In the context of energy interventions, a direct rebound effect example would be a family that has purchased a new energy-efficient dishwasher, the so-called eco-friendly product, and that is likely to increase the number of uses of the product or to feel justified in increasing the use of another energy-demanding product in the house, which would offset the expected beneficial gains of reduced energy use and consequently CO2 emissions [36]. The eco-friendly product would reduce the environmental burden of the house if the behavior remained the same, but people may also begin to use the product more often leading to overuse. An indirect rebound effect occurs when, for example, people improve the insulation of their houses to reduce their heating energy bill [37]. The rebound occurs when the saved money is used to perhaps purchase new energy-using equipment (adds to the consumption) [38] or even to take on more greenhouse gas-emitting activities like flights abroad for vacations and tourism [39] due to the extra money obtained from energy saving. The rebound effect has previously been linked to what is called “moral licensing”—people feel they can justify a morally inappropriate behavior by adopting morally appropriate ones [40]. Here, particularly regarding direct rebounds, the suggested framework adds the view that the averaging heuristic could be one of the reasons why people end up adding or using an extra piece of energy-demanding equipment because they overestimate the benefits of the new efficient product.

The framework suggests that the misconceptions outlined herein as well as other related misconceptions may have their roots in the limited capacity of human information processing. Thus, it suggests that the cognitive underpinnings of rebound effects as well as moral licensing and the cognitive misconceptions about environmentally related objects and behavior come from the adopted mental averaging heuristic. The same mechanism can also explain other related phenomena such as the assumption that moral cleansing can be achieved by pro-environmental actions [41].

3. Discussion and Conclusions

Understanding how people think and process information, particularly on matters concerning an important topic such as climate change, is important because it gives insights into how the public will receive, use, and behave regarding specific sustainability interventions. This communication proposed and explained that environmental harmful behavior may not necessarily be out of disregard but could have roots in cognitive processes adopted when making environmentally related evaluations of behavior or interventions. The framework suggests a range of testable hypotheses for future research. According to the framework, for example, people embrace the production and consumption of eco-labeled produce even if such consumption still causes an environmental burden. They also exaggerate and overgeneralize the benefits of sustainability interventions or energy-efficient products and willingly accept policies of greenhouse gas emission cuts even if these cuts are insufficient for alleviating climate change, because they are likely to believe that small greenhouse gas emission cuts can compensate for past large emissions. Another interesting implication here is not how people accept or buy into policy changes but rather how the politicians perceive—and promote—their policy proposals. Likewise, companies that are reinventing themselves with a green marketing mix and eco-labeling strategies to gain market advantage [42,43], which are also likely to be adopted by carbon-intensive companies, may likely be viewed by the general public as adopting sustainable measures, while in reality these companies are not (an example here is the so-called sustainable fast fashion). The framework thus has implications for the success of sustainability interventions and policymaking.

Other areas of interest include an investigation on the extent and strength of the averaging bias on different behaviors or objects, as some are symbolic of sustainable and others of unsustainable lifestyles (ones with a strong public opinion). How do people perceive and evaluate these symbolic behaviors or other behaviors while they compete with their needs? Additionally, further investigation is needed to assess whether domain experts and professional decision makers demonstrate the averaging bias. Finally, what can we do to improve evaluations and decision-making by removing the bias? Can different ways of framing policy or, alternatively, labelling products reduce the effect on the carbon footprint illusion and the averaging bias? For example, one could drop the use of terms such as “eco-friendly”, “eco-product”, or “environmentally friendly”, or related terms, and adopt a more representative approach that reflects the actual impact on the environment (e.g., a simplified form of life cycle assessment of an object).

From a broader perspective, an investigation is needed on how public opinion can be influenced to accept stringent sustainability measures while avoiding the pitfalls of the averaging heuristic. For example, the European Union is pushing a directive about a longer lifetime for products, which will result in decreased emissions due to raw material acquisition and production of goods [44]. How will the public respond to longer product lifespans? Considering we live in a circular economy and have a “throw-away lifestyle” [45] where it is commonplace to buy trendy clothes every month and new phones every year, will people be willing to use the products for longer and how will this influence their self-view and behavior?

In summary, the proposed cognitive framework assumes that many environmentally harmful behaviors are the emerging property of an averaging bias, which may imply an overestimation of emission reduction measures in people’s judgement. When people see or otherwise experience “environmentally friendly” and “harmful” objects and/or actions in combination, their evaluation of the environmental impact of the total set is lower than the sum of the individual components, because they adopt a mental averaging heuristic. This heuristic is employed to facilitate human information processing in the face of difficulties, without accurately assessing the sum of a mix of “environmentally friendly” and “harmful” sources. This communication attempts to show the explanatory potential of this framework in addressing how averaging can explain several behavioral phenomena, including the “green is good” and the “green compensation” misconceptions, the negative footprint illusion, compensatory green beliefs, and rebound effects.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges Professor Patrik Sörqvist for his contributions, mentorship, and guidance.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- American Psychological Association. Society’s Grand Challenges: Insights from Psychological Science; American Psychological Association: Worcester, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Figueres, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; Whiteman, G.; Rockström, J.; Hobley, A.; Rahmstorf, S. Three years to safeguard our climate. Nat. News 2017, 546, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookes, L.G.; Grubb, M. Energy efficiency and economic fallacies: A reply; and reply. Util. Policy 1992, 20, 390–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitnis, M.; Sorrell, S.; Druckman, A.; Firth, S.K.; Jackson, T. Turning lights into flights: Estimating direct and indirect rebound effects for UK households. Energy Policy 2013, 55, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillingham, K. The Consumer Response to Gasoline Price Changes: Empirical Evidence and Policy Implications. Ph.D. Thesis, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vivanco, D.F.; Kemp, R.; van der Voet, E. How to deal with the rebound effect? A policy-oriented approach. Energy Policy 2016, 94, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, D.M.; Welch, B. Debate: To nudge or not to nudge. J. Polit. Philos. 2010, 18, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hukkinen, J.I. Addressing the practical and ethical issues of nudging in environmental policy. Environ. Values 2016, 25, 329–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, s.v. “Affordance (n.)”. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/affordance (accessed on 7 January 2020).

- Kaaronen, R.O. Affording sustainability: Adopting a theory of affordances as a guiding heuristic for environmental policy. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachrisson, J.; Boks, C. Exploring behavioural psychology to support design for sustainable behaviour research. J. Des. Res. 2012, 10, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. Influencing policymakers. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2017, 7, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntanos, S.; Arabatzis, G.; Chalikias, M.S. The Role of Emotional Intelligence as an Underlying Factor Towards Social Acceptance of Green Investments. In Proceedings of the HAICTA, Chania, Greece, 21–24 September 2017; pp. 341–351. [Google Scholar]

- Ntanos, S.; Kyriakopoulos, G.; Skordoulis, M.; Chalikias, M.; Arabatzis, G. An application of the New Environmental Paradigm (NEP) scale in a Greek context. Energies 2019, 12, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, A.; Hansla, A.; Heiling, J.M.; Bergstad, C.J.; Martinsson, J. Public acceptability towards environmental policy measures: Value-matching appeals. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 61, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R. The dragons of inaction: Psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewandowsky, S. Future global change and cognition. Top. Cogn. Sci. 2016, 8, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sörqvist, P. Grand challenges in environmental psychology. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernev, A.; Gal, D. Categorization effects in value judgments: Averaging bias in evaluating combinations of vices and virtues. J. Mark. Res. 2010, 47, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilovich, T.; Griffin, D.; Kahneman, D. Heuristics and Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgment; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; ISBN 0521796792. [Google Scholar]

- Joireman, J.; Truelove, H.B.; Duell, B. Effect of outdoor temperature, heat primes and anchoring on belief in global warming. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, B.R.; Kary, A.; Moore, C.; Gonzalez, C. Managing the Budget: Stock-Flow Reasoning and the CO2 Accumulation Problem. Top. Cogn. Sci. 2016, 8, 138–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterman, J.D.; Sweeney, L.B. Understanding public complacency about climate change: Adults’ mental models of climate change violate conservation of matter. Clim. Chang. 2007, 80, 213–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, S.; Kashima, Y.; Walker, I.; O’Neill, S. Comparing the atmosphere to a bathtub: Effectiveness of analogy for reasoning about accumulation. Clim. Chang. 2013, 121, 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmgren, M.; Andersson, H.; Sörqvist, P. Averaging bias in environmental impact estimates: Evidence from the negative footprint illusion. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 55, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaklamanou, D.; Jones, C.R.; Webb, T.L.; Walker, S.R. Using public transport can make up for flying abroad on holiday: Compensatory green beliefs and environmentally significant behavior. Environ. Behav. 2015, 47, 184–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sörqvist, P.; Langeborg, L. Hurting the world you love. New Sci. 2019, 241, 24–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sörqvist, P.; Langeborg, L. Compensating for Climate Misdeeds Can Make You a Worse Carbon Emitter; New Scientist: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fotostock, A. The price of fast fashion. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Drew, D.; Yehounme, G. The Apparel Industry’s Environmental Impact In 6 Graphics; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Gorissen, K.; Weijters, B. The negative footprint illusion: Perceptual bias in sustainable food consumption. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmgren, M.; Kabanshi, A.; Langeborg, L.; Barthel, S.; Colding, J.; Eriksson, O.; Sörqvist, P. Deceptive sustainability: Cognitive bias in people’s judgment of the benefits of CO2 emission cuts. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 64, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmgren, M.; Kabanshi, A.; Marsh, J.E.; Sörqvist, P. When A+B <A: Cognitive bias in experts’ judgment of environmental impact. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 823. [Google Scholar]

- Sorrell, S.; Dimitropoulos, J. The rebound effect: Microeconomic definitions, limitations and extensions. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 636–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessoe, K.; Rapson, D. Knowledge is (less) power: Experimental evidence from residential energy use. Am. Econ. Rev. 2014, 104, 1417–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, H. Is what we think of as “rebound” really just income effects in disguise? Energy Policy 2013, 57, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.A.; Azevedo, I.L. Estimating direct and indirect rebound effects for US households with input–output analysis Part 1: Theoretical framework. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 86, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapeller, M.L.; Füllsack, M.; Jäger, G. Holiday Travel Behaviour and Correlated CO2 Emissions—Modelling Trend and Future Scenarios for Austrian Tourists. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiefenbeck, V.; Staake, T.; Roth, K.; Sachs, O. For better or for worse? Empirical evidence of moral licensing in a behavioral energy conservation campaign. Energy Policy 2013, 57, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazar, N.; Zhong, C.-B. Do green products make us better people? Psychol. Sci. 2010, 21, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, E.A.; Royhan, P.; Rahman, M.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Mostafa, A. The Impact of Enviropreneurial Orientation on Small Firms’ Business Performance: The Mediation of Green Marketing Mix and Eco-Labeling Strategies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moravcikova, D.; Krizanova, A.; Kliestikova, J.; Rypakova, M. Green Marketing as the Source of the Competitive Advantage of the Business. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvo, C.; Peck, D.; Rietveld, E. A Longer Lifetime for Products: Benefits for Consumers and Companies; Study for Internal Market and Consumer Protection (IMCO) Committee; European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wieser, H. Beyond planned obsolescence: Product lifespans and the challenges to a circular economy. GAIA-Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2016, 25, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).