Abstract

Examination plays a vital role in the present contemporary educational setting as well as serving as an indicator and yardstick to place students in relation to their examination scores after they undergo the examination. However, students at different educational levels experience examination anxiety, which can interfere with making right decisions either before or during examinations and is considered to be a phenomenon associated with low examination scores. Therefore, the present research study was aimed at determining the mediating effect of positive psychological strengths between study skills and examination anxiety among Nigerian college students. The study employed survey research on 315 Nigerian college students. The result of the path analysis shows that study skills (SSK) have a significant and direct relationship on examination anxiety. The mediation between positive psychological strength (PPS) and examination anxiety is identified as being effective and significant. Therefore, positive psychological strength (PPS) acts as an effective mediator towards examination anxiety.

1. Introduction

Examinations are considered to be important in many educational organizations, being used as instruments to measure students’ academic ability [1,2]. Several researchers report reasons for classifying students according to their mental capabilities such as background, age, and intelligence, thus arranging homogeneous groupings so that students can be provided with proper educational opportunities according to their capabilities. This approach is also used in the promotion of students to a higher grade level [3,4]. Researchers have also supported the concept that examination results could be used to make decisions on the promotion of workers in their chosen professions and careers [5]. Furthermore, examinations can aid in improving the learning process. As well as providing educational, vocational, and personal guidance, examination results are useful in numerous educational disciplines, particularly in the field of psychology [6,7]. According to Amanya et al. (2018) [8], in the Nigerian context, aptitude and achievement test scores, as well as academic performance, are increasingly used in the evaluation of applicants for admission into educational programs [6]. However, research is needed to examine the relationship between study skills, positive psychological strengths, and examination anxiety; this is of paramount importance for educational institutions, particularly for students of higher education institutions because it serves as a yardstick for placement into promotional and evaluative scenarios. Some research evidence supports the idea that apprehension of threatening events in general is a broad-based anxiety associated with either real or anticipated communication or tasks of any sort, and that such apprehension may cause students to view evaluative situations as threatening, more specifically pertaining to examinations [9]. Hence, the aim of this study, among other objectives, is to examine the relationship between study skills, positive psychological strengths, and examination anxiety at a government college in Nigeria. This study was warranted by findings in prior research indicating that there are high levels of examination anxiety among Nigerian government college students and that this is related to factors such as ineffective study skills, poor quality of teachers, and conventional methods of teaching [10,11]. Students’ home background was identified as another factor [12].

According to Olanipekun [13], studies on examination anxiety and study skills among college students show that study skills have a significant impact on students’ examination anxiety. Therefore, the researcher hypothesizes that the level of study skills is related to the level of examination anxiety; the higher the level of study skills, the lower the level of examination anxiety [14]. This signifies that large numbers of students in Nigeria experience examination anxiety. When compared to other parts of the world, it is notable that the factors responsible for students experiencing examination anxiety differ from one country to another. Therefore, this research study employed the students of National Certificate of Education (NCE) 1 Kashim Ibrahim College of Education in Borno, Nigeria. With a total sample of 315 students, the representatives were drawn from four departments. Ten students, seven males and three females, were from the school of arts. Two hundred and three students, 120 males and 83 females, were from the school of education. Twelve students, eight males and four females, were from the school of languages. Ninety students, 57 males and 33 females, were from the school of science.

1.1. Positive Emotions Theory

Barbara Fredrickson and her ‘Broaden-and-build’ theory explained that positive emotions can build young adults’ physical, intellectual, and social abilities. She hypothesized that by broadening awareness and thought-action repertoire, humans would look for creative and flexible ways of thinking and acting. This broadening effect can lead to the establishment of skills and resources over time. Her studies showed that people who experience positive emotions are able to make more connections, create more inclusive categories, and have heightened levels of creativity. Not only do positive emotions help us perform better at examinations, they also help us to perform better at work, as well as strengthening our relationships with others.

1.2. Importance of Positive Psychological Strengths as Mediating Variable

Therefore, this research study has adopted positive psychological strength as a mediating variable. It is necessary to use mediation variables in some research studies, and it is especially fundamental in the field psychology [15]. The rationale of employing positive psychological strength as a mediator variable is to test for the type of model that has the ability to overcome problems with the conventional method, and that it can be applied to a wide range of models [16]. Central to the concept of mediation, a mediator has the power by extending a simple causal inference where the predictor causes an outcome, and the mediator intervenes the relationship. Therefore, a variable that is influenced by the predictor and in turn influences the outcome is a mediator [17]. Positive psychological strength is therefore important as a mediator variable because it has the strengths to examine the indirect effects of a research study. It is important to use the mediator to identify the focal elements of a given theory testing with mediation analysis. However, to estimate the extent to which the mediation process explains the relationship between study skills as predictors and examination anxiety as an outcome, it is also necessary to consider the direct effect [18].

1.3. Positive Psychological Strengths as Mediating Variable

There are several avenues for researchers, educators, and teachers to instill positive psychological strengths strategically [19]. Very often, teachers are urged to improve learner’s strengths psychologically because this is an important mediator, but problems may arise when teachers do not have the same psychological perception as their students in a classroom setting. However, 10 of the 14 traditional strategies to develop psychological strength were perceived similarly by both the students and the teachers in a study [20]. Therefore, it is important to address both approaches and the various processes involved in classroom activities because these would also serve as mediating elements [21].

Hope-based therapy protocol defines hope as a cognitive means in which a person can obtain his/her goal [22]. For a long period of time, this therapy was used to overcome mental illness [23]. The conventional understanding was that hope-based therapy is linked to a pathological replacement of psychotherapy and is believed to be a means of overcoming mental illness. This is widely accepted among psychological researchers, and it is also linked to positive psychological strengths [24].

1.4. Self-Efficacy as a Sub-Construct of Positive Psychological Strengths

Among existing research studies, many have examined self-efficacy and believe that high self-efficacy has a positive impact among pre-service elementary school teachers. Furthermore, their study placed special reference to gender. Self-efficacy is the technique of acquiring methods or skills that are progressively, exclusively, and/or primarily practiced within a social group [25,26]. Positive psychological strengths can help in developing the potential empowerment within oneself towards goal actualization [27]. A study looked into how to improve the self-efficacies of teacher candidates. Thus, it is necessary to provide teachers with opportunities to attend classroom activities through question-and-answer sessions, discussions, simple lessons, lesson planning, making use of library facilities, and using technology [28]. Self-efficacy is broadly seen as a positive personality trait that enables a person to bounce back from either trauma, worries, nervousness, or negative situational circumstances [29,30]. The researchers also stated that people with self-efficacy mostly possess internal loci of control in terms of a positive self-image, self-efficacy, and hardness. They excel at actively strategizing these positive characteristics; therefore, they are often associated with better psychological adjustment, higher life satisfaction, and lower psychological distress [31].

1.5. Resilience as a Sub-Construct of Positive Psychological Strengths

With the emergence and appearance of positive psychological strengths, more attention has been given to transforming what is wrong with people into what is right with people [32]. It was further identified in another study that it is important to focus on resilience, which is a big part of psychological strength [32,33]. It has been pointed out that psychological resilience is negatively related to behavioral problems. College students often display psychological disposition or problematic behaviors when they are exposed to stressful circumstances, especially during academic examination seasons [34]. The authors stated that psychological resilience is actually a much broader term than just resilience, which is usually defined as flexibility and durability. For psychological resilience, the term actually represents the process of efficiency in addressing undesirable situations in life [34]. Resilience is often portrayed as a set or combination of different skills that enable individuals to effectively overcome substantial stress resulting from adversity. In other words, it represents the strength of an individual to be able to push them self out from a negative experience [35]. Resilience is found to be correlated with self-satisfaction and positive emotion. In many instances, self-efficacy predicts life satisfaction. Research studies have shown that individuals who possess psychological resilience have a higher chance of preventing themselves from misusing or abusing drugs, alcohol, and other substances [36].

1.6. Optimism as a Sub-Construct of Positive Psychological Strengths

The concept of optimism is defined as a generalized expectation of a positive future [37]. Optimism is part and parcel of lifetime development because it functions to establish interactions between individuals and their environment. Any changes that occur may eventually have some effects on that developmental aspect of life. However, some studies have claimed that optimism and pessimism were distinct systems under the field of behavioral genetics [38]. Some researchers reported optimism as one of the components of positive psychological resources that plays a role in generalizing and stabilizing expectations in individuals, providing them with anticipations for positive outcomes [39]. A number of research studies have indicated that differences in the level of optimism greatly determine how an individual feels, and how he approaches certain challenging activities or problematic situations. Under such circumstances, optimists can expect a positive outcome, and these expectations are often related to positive psychological strength. In contrast, pessimists would anticipate negative end results, due to a lack of positive psychological strengths [40]. Individuals with a high degree of optimism have also been found to possess a high level of desire and positivity to withstand difficult situations [41]. In another study, the findings substantiated that positive psychological attributes like optimism appeared to be able to minimize unwanted behaviors that could hinder or negatively affect students’ academics activities.

Hence, optimism is a positive predictor of psychological well-being [42]. Many researchers suggested that conceptualization of happiness is related to many psychological variables, constructs, and sub-constructs. To achieve actual happiness, more so optimism, the subjective well-being and general ability of an individual play a significant role. The positive effect of optimism can be mostly explained based on the expectancy-value model [43]. Another researcher suggested that optimism is helpful in progressive learning. Professional learning that is centered on developing self-efficacy will directly benefit individuals whereby they can gain positive psychological strengths [43]. Similarly, research in many other dimensions has also demonstrated the vital role of optimism in the quality of life of individuals, especially at the college level. Study findings also supported the fact that while most major personality traits are correlated to the positive aspect of human development, optimism has been the most researched since the emergence of the idea of positive psychological strengths [44].

1.7. Hope as a Sub-Construct of Positive Psychological Strengths

Hope is the positive anticipation and a state of readiness wherein an individual immerses himself in a certain activity in order to achieve a goal [45]. In another research study, it was pointed out that hope is an important aspect in the lives of human beings, especially for those with a lower level of well-being. Hope is found to have a positive relationship with psychological well-being, and hope is also a significant predictor of life satisfaction [46]. Research studies have found that the presence of hope among a group of parents with ill children enabled these parents to deliver empathic consideration to others who were experiencing severe illnesses through positive psychological strengths. The same behavior was observed among formal and informal caregivers [45]. Furthermore, hope was also identified as a sub-set of positive psychological strengths, especially in situations that depend on goal setting [45]. A systematic review of positive psychological strengths includes hope-building, and labelled hope as a human psychological strength that plays a vital role in both cognitive and affective processes. Hope can help an individual possess positive expectation to attain a goal [46]. However, researchers also observed that hope encompasses both positive and negative judgments. Hope can either negatively or positively affect the state of uncertainty in certain situations as they happen, thus leading to different outcomes [45]. Hope as a sub-construct of positive psychology consists of three components; namely goal, pathway, and agency. Several research studies suggested that hope is positively associated with increased self-esteem, optimism, psychological well-being, positive thoughts, resilience, and physical health. Hope has no relation to depression [47]. From a positive psychological perspective, Uysal [47] considered hope to be a positive psychological strength in humans, and that hope represents the cognitive process that helps individuals to have a positive expectation to reach desired zeal, as well as help individuals perceive their desire as an achievable target [47].

1.8. Research Objectives

The research review led us to formulate the following objectives for this study, as follows:

- To determine the level of positive psychological strengths among Nigerian college students;

- To analyze the relationship between study skills and examination anxiety among Nigerian college students;

- To analyze the effect of positive psychological strengths as a mediating variable on examination anxiety among college students.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

This study used, as the target population, the National Certificate of Education (NCE) students of Kashim Ibrahim College of Education (KICOE) in Borno, Nigeria, with a total number of 2003 students. However, for this research, NCE 1 students were recruited, and the researcher used the whole population of 315 students for this survey research. In order to analyze the levels of examination anxiety among Kashim Ibrahim College of education students, frequency distribution was used. In this study, three questionnaires were used to collect data among the college students. Firstly, a study skills questionnaire was adapted [48], consisting of 21 items to determine the level of study skills among the college students. Secondly, another questionnaire used in this study was the Examination Anxiety Questionnaire, developed by Spielberger (1995) [49]. A 20 item, four points Likert scale questionnaire was modified to suit the present study. Lastly, a positive psychological strength questionnaire by Luthans, Youssef, and Avolio (2007) was used [50]. This questionnaire consisted of 24 items of positive psychological strengths, which measured four different dimensions of hope, self-efficacy, optimism, and resilience. The scale was adapted to form a four point Likert scale ranging from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree. As an ethics procedure, all respondents signed the consent form as an agreement to participate in this research.

2.2. Procedure

Initially, the students were given a written informed consent form to sign, after which an examination anxiety questionnaire was given to the students; an adequate amount of time was allotted to complete it. Confidentiality and anonymity were ensured. Respondents were asked to read the instructions, which were written on the top of the questionnaires, carefully. The students were also instructed to answer the questions as honestly as possible. The study used the entire population of 315 students for the survey research. The data was obtained by administering the questionnaire on examination anxiety. The questionnaire was given to the students immediately after the end of semester examination; all students were asked to remain in their seats and complete the questionnaire before leaving the examination hall. The self-administered questionnaires were given to students during class

3. Measures

3.1. Positive Psychological Strengths, Study Skills and Examination Anxiety

The study used three sets of questionnaires, including the study skills questionnaire, the positive psychological strengths questionnaire, and examination anxiety questionnaire. The questionnaires were adapted to measure the three main variables; study skills, positive psychological strengths, and examination anxiety. The data collection instrument for the Positive Psychological Strengths Questionnaire (PPSQ) was adapted from the one developed by Luthans, Youssef, and Avolio, 2007 [50]. It was comprised of 24 items of positive psychological strengths. This instrument includes four construct dimensions with question items under each sub-measure. The sub-measures are Hope, Self-efficacy, Optimism, and Resilience. The scale was originally a five point scale; however, because complaints were forwarded by the respondents, for easy understanding, the researcher dropped one of the scale points and made a five point scale with question items anchored from “1” (strongly disagree) to “5” (strongly agree). Examples of the items include “I feel confident helping to set targets/goals in my study” (confidence); “I can think of many ways to reach my current goals” (hope); “When things are uncertain for me when I study, I usually expect the best” (optimism), and “I usually take stressful things at study in my stride” (resiliency). Luthans et al. (2007; alpha = 0.88) [50]. The study skills questionnaire was adapted from Cottrell (2003) [48] and there were additions and deletions done to modify from the adapted instrument in order to be consistent with the present research work. The questionnaire consists of a four-dimensional construct ranging from note taking, planning and organizing time for reading, learning and remembering, and reading motives. The scale is anchored from “1” (strongly disagree) to “4” (strongly agree). Examples of items include, under note taking, “I keep a good set of notes for each course I study”, under time management, “Before I prepare my revision timetable, I plan how to spend my time”, and under learning and remembering, “After reading my lecture notes, I test myself”. Cottrell (2003; alpha = 79) [48] was used to measure the study skills, with response choices ranging on a four point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = agree, 4 = strongly agree). Reliability coefficients of the current study for all the components were greater than the 0.75 Cronbach alpha reported. The Test Anxiety Questionnaire (TAQ) by Spielberger (1995) [49] has 21 items, which measure test anxiety. An inventory developed by Spielberger (1995) [49] has 20 items to test anxiety; this inventory was adapted from Spielberger (1995) [49] with a few modifications to suite this present study. The modifications were accorded with four-dimensional items; the sub-measures included worry, nervousness, apprehension, and tension. The scale items were anchored from “1” (strongly agree) to “4” (strongly disagree). Examples of items include “While taking important examinations, I have an uneasy feeling” (uneasiness); “During important examinations, I am so tense that my stomach get upsets” (tension); “During examinations, I get so nervous that I forget facts that I really know” (nervousness), and “If I were to take an important examination, I would worry a great deal about taking it” (worry).

3.2. Reliability

The data collected were subjected to analysis in order to identify the reliability of the instrument and were indicated according to Cronbach alpha. The instrument shows that a person with examination anxiety had a reliability = 0.73, item reliability = 0.72. Positive psychological strengths person reliability = 0.86, item reliability = 0.72, and study skills person reliability = 0.76, item reliability = 0.76, respectively.

3.2.1. Study Skills Questionnaire

Table 1 indicates that the person reliability of the study skills (SSK) questionnaire is 0.76. Moreover, item reliability also separately indicated 0.76. Therefore, the questionnaires maintained a very good result in both person and item reliability because the Cronbach alpha reliability is more than 0.6 statistical value.

Table 1.

Study Skills Pilot Results.

3.2.2. Positive Psychological Strengths

Table 2 shows the person’s reliability of positive psychological strengths (PPS) questionnaire shown in Table 6. Moreover, item reliability also separately indicated 0.72. Therefore, the questionnaire has excellent reliability. The Cronbach alpha, indicated at 0.72, shows a very good item reliability. For this reason, the Cronbach alpha reliability has more than 0.6 statistical value.

Table 2.

Positive Psychological Strengths Pilot Results.

Table 3 indicates the person’s reliability for the examination anxiety (EA) questionnaire, shown in the table as 0.73. Moreover, item reliability is also separately indicated as 0.72. Therefore, the questionnaires maintained very good results for both person and item reliability. For this reason, the Cronbach alpha reliability is more than 0.6 statistical value.

Table 3.

Examination anxiety Pilot Results.

4. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed in accordance with the objectives set by the study. Objective 1 was determined using an Item-Person Map. Objectives 2 and 3 were determined using Structural Equation Model Partial Least Square.

4.1. Objective 1 Levels of Study Skills

The content of Table 4 are the product of the Figure 1 Rasch measurement model of person/item map distribution of the positive psychological strengths. This shows that the respondents involved had moderate study skill level (logits) ranges from 00 to 0.99 among KICOE students.

Table 4.

A and B Display the Level of Moderately Weak Positive Psychological Strengths and Percentage among Kashim Ibrahim College of Education (KICOE) Students.

Figure 1.

Path analysis for Examination and positive psychology.

In Table 4, A indicates positive psychological strengths and consists of 17 students (5.4%), out of which, 11 (3.5%) were male while 6 (1.9%) were female. Additionally, the school of arts recorded no students and the school of education indicated 13 (12%) students. Only one student was recorded under the school of language and 3 students were recorded under the school of sciences.

In Table 4, Level B shows the school and gender involved under level B, with a total of 130 students (41.3%); 71 (22.5%) students were recorded as male and 59 (18.7%) students were recorded as female. Moreover, the school of arts showed three students and the school of education recorded one hundred and three.

In Table 5, level C has a cumulative number of 122 students. Under this level, 69 (21.9%) of the students were male while 53 (16.8%) were female.

Table 5.

C and D Display the Weak Level of Positive Psychological Strengths by Logit and Percentage among KICOE Students.

In Table 5, level D has a total of 32 (10.2%) students; 13 (4.1%) of which were male and 19 (6.0%) were female. The school of education had 11 respondents.

In Table 6, level E displays positive psychological strengths; the number of schools and students involved are presented with their percentages. Under this level, the categories are comprised of 10 (3.2%) students, out of which, 7 (2.2%) are recorded as male while 3 (1.0%) were female.

Table 6.

E and F Display the Very Weak Level of Positive Psychological Strengths by Logits and Percentage among KICOE Students.

In Table 6, Level F is the last table under this category, indicting a total of 4 (1.2%) students; 2 (0.6%) of which were male and 2 (0.6%) were female.

4.2. Objective 2 Relationship Between Study Skills and Examination Anxiety

This part of the research study presents the analysis of research question four, which addresses the research question: Is there any relationship between study skills and examination anxiety? In order to analyze this research question, it is important to determine the relationship between study skills and examination anxiety among Nigerian college students. The results of this study were presented according to the research objectives. The findings were mainly based on inferential analysis by applying path analysis and structural analysis. The main purpose of conducting path analysis was to assess the direct and indirect relationships between the variables, while structural analysis is used to predict the development of the model. The study recruited 55 students who were identified from a sample of 315 students.

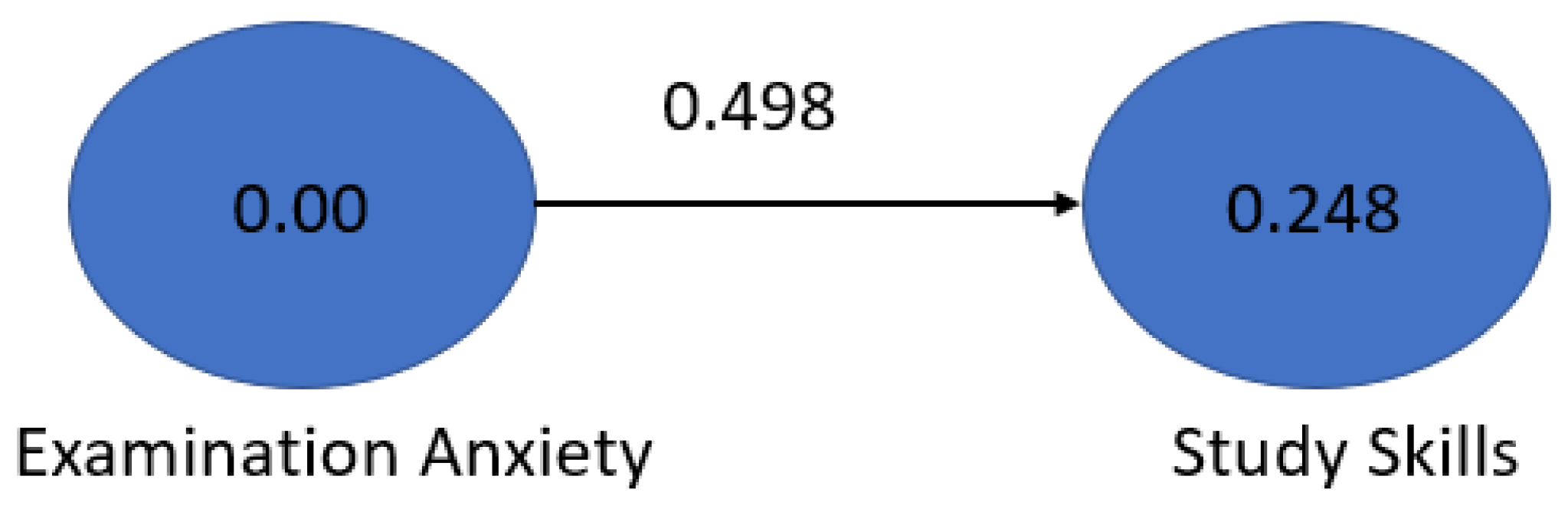

The research question was “Is there any relationship between study skills and examination anxiety?” To obtain the outcome of the analyses, partial least squares (PLS) was employed to analyze the relationship in the path analysis, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows the relationship between study skills and examination anxiety. The result of the path analysis shows that study skills (SSK) have a significant and direct relationship with examination anxiety. The relation is positive with a path coefficient (β =0.498, t = 2.06, p < 0.05). This result indicates that study skills contribute to students positively managing their examination anxiety. Therefore, a null hypothesis is rejected.

4.3. Objective 3 Positive Psychological Strengths as Mediating Variable on Examination Anxiety among Nigerian College Student

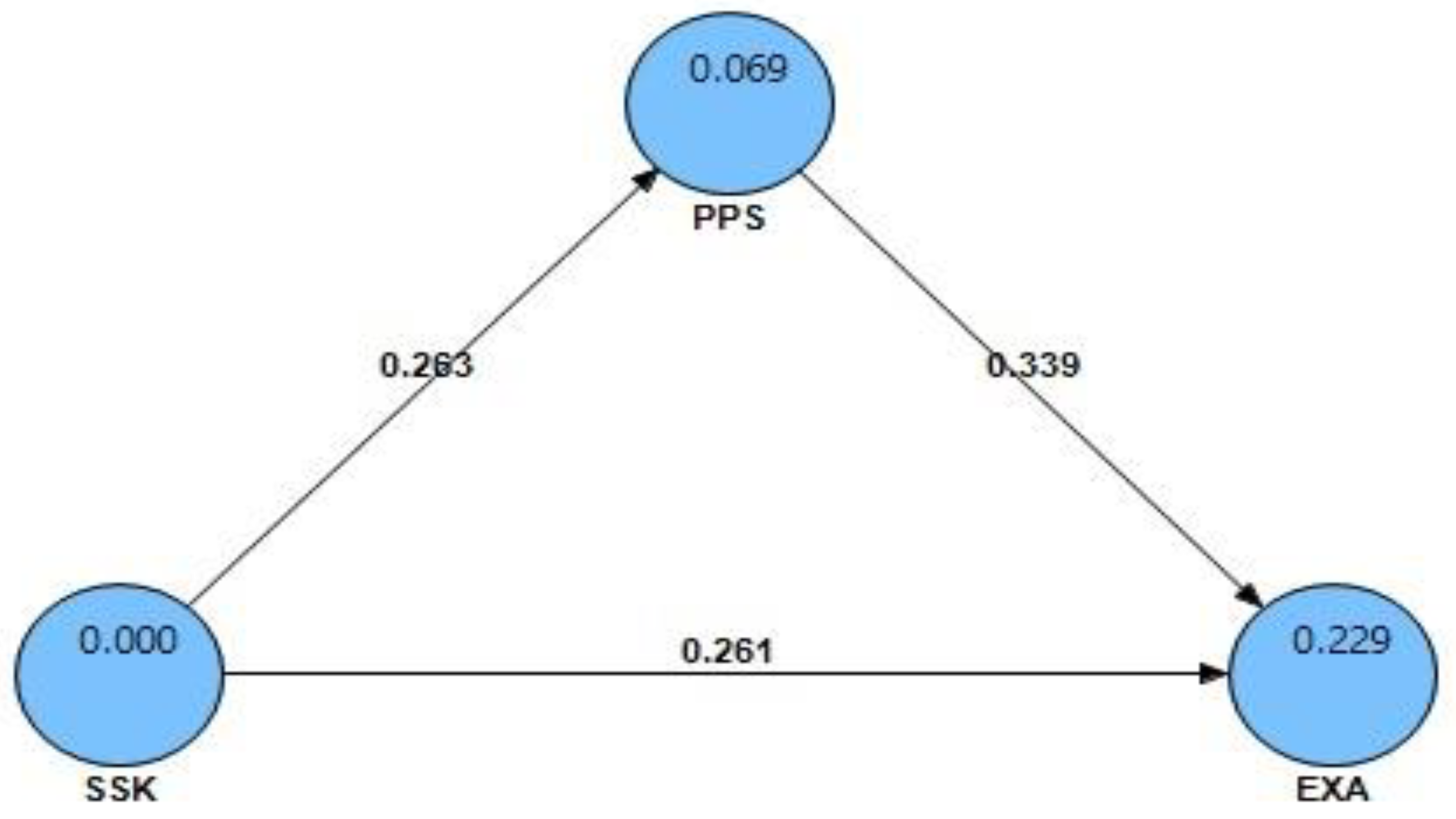

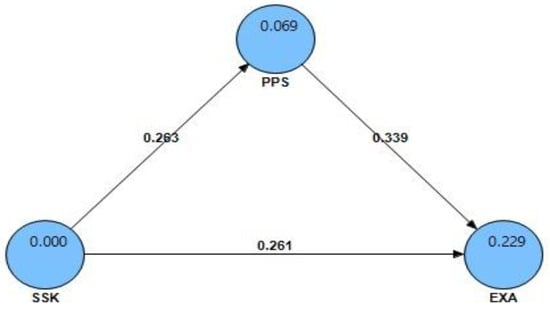

Research question 3 was “Do positive psychological strengths have an effect as a mediating variable on examination anxiety?” Structural analysis was applied to answer this research question, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Effects of positive psychological strengths (PPS) as Mediating Variables EA.

Figure 2 shows the structural analysis model of the effects of positive psychological strength (PPS) as a mediating variable. This indicates the structural path, revealing an acceptable relationship. The strengths of the relationship between the variable are, thus, SSK (β = 0.261, t = 1.99, p < 0.05), EXA (β = 0.339, t = 2.98, p < 0.05), and PPS (β = 0.339, t = 2.87, p < 0.05). The value of mediation is sufficient when (f2 > 0.08.) This demonstrates the value of study skills and their relationship with positive psychological strength. The mediation between positive psychological strengths (PPS) and examination anxiety is identified as effective and significant. Therefore, positive psychological strengths (PPS) acts as an effective mediator towards examination anxiety.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Positive psychological strengths

Positive psychological strengths (PPS), as one of the central constructs in this study, can be categorized into six levels. The six levels were determined using the statistical tool, Winstep. It displays the sequence of the levels in logits in the following hierarchical scale; outstanding, excellent, good, moderate, moderately weak, weak, poor, and fail. This research study produced a good level of PPS, whereby a substantial number of the students were categorized under a good level. Acquiring adequate and appropriate PPS would positively contribute to high examination scores, relieve the level of anxiety, and improve the psychological wellbeing of the students.

In a 2017 study, the psychology of positivity and strengths-based approaches at work was explored, especially in terms of the nature of the psychology of positivity and how strength-based approaches were used [51]. Similar to this study, which explored three levels (subjective level, individual level, and group level), this study also used the same number of construct measures in terms of the three main variables that were examined on their levels.

It is also a well-known fact that a large number of students gained entry to college without having the necessary knowledge about PPS. Previous research studies conducted focused mainly on the psychological capacity in industrial or workplace organizations. Only very recently was the attention of the researchers shifted towards academic institutions. With that, there has been slow but tremendous progress regarding issues surrounding the PPS of students [52].

As part of the study findings, the roles and importance of PPS were established. There was a clear linkage between the various literature reviewed in this study and the postulated theory of “Build and Broaden”. It also clearly showed that PPS consists of four sub-constructs, including hope, self-efficacy, optimism, and resilience. Luthans et al. (2007) [50] concluded that PPS provides hope, resilience, efficacy, and optimism and these elements are all related to performance and satisfaction.

Another study in 2010 tested a model among teachers to find out about the motivational potential of different job resources [53]. However, while they concluded that intervention and a work environment should be optimized at an individual level in an educational institution, it is necessary to remember that their study was conducted among teachers and not students. Researchers have also studied the perception and sources of stress and have investigated the types of coping mechanism used. Various methods used to decrease the stress level were also studied. In short, they recommended that stress management should be made part of the school curriculum in order to equip students with suitable methods to reduce their stress levels. These recommendations were similar to our study [54].

Furthermore, this study showed that PPS is a crucial mediating variable and a valuable component in the field of psychology towards the management of examination anxiety. This is particularly true for those who lack adequate and effective study skills.

5.2. Hope as an Important Component of Positive Psychological Strengths

Researcher [55] addressed how the field of positive psychology has been developing and flourishing among all the psychology-related fields in the past few years. In their study, they examined the dynamic interplay of positive and negative experiences. They used hope as a critical component of positive psychology. The process of obtaining hope is considered as constantly evolving and maturing as a discipline and further suggested this could be one of the ways to attain a future scholarship. Hope was also used as a sub-construct in our study, signifying the importance of hope in this aspect [56,57]. Other studies further cemented on the need for training in positive psychology to increase hope among individuals to enable them to set realistic and relevant goals [47].

5.3. Optimism as Important Component of Positive Psychological Strengths

Two recent studies reiterated the role and importance of optimism as a component of positive psychology [58,59]. In their studies, they explored the relationship between mental toughness and coping, mental toughness and optimism, and coping and optimism. They managed to establish relationships among the variables measured, and they also emphasized the need for intervention in the form of training in mental toughness. Therefore, their findings were similar to this study, in which some of the sub-constructs, such as optimism, served as a critical component of positive psychological strengths. Their assertion and the report on optimism was supported by Yee et al. (2010) [60], affirming that optimism served as a mediator in the relationship between meaning in life and both negative and positive aspects of well-being. Furthermore, the study concluded that optimism and meaning in life had an impact on the life satisfaction of adolescents [61].

5.4. Self-efficacy as Potential Mediator under Positive Psychological Strengths

Cardon and Kirk (2015) [62] and Wang et al. (2014) [26] looked at the self-efficacy of entrepreneurs between those who persisted in their venture and those who quit. Their studies found that passion enhanced persistence. They also observed a relationship between self-efficacy and persistence that signified that self-efficacy may sustain entrepreneurial action. Therefore, it was concluded that self-efficacy served as a good mediating factor for entrepreneurial passion and was considered to be a predictor of self-efficacy and persistence. These findings coincided with our study in terms of the role of self-efficacy as a mediating variable under real psychological strength. However, there were some slight differences in terms of the approach to the research problem and the target population. Another two recent studies supported the claim that self-efficacy is a potential mediator. The studies examined the relationship between the four components of career adaptability and suggested that high adaptability among undergraduate students was significantly linked to a higher level of academic satisfaction [63,64].

In summary, it can be concluded that it is paramount to assess students’ self-efficacy when deciding the student’s choice of career. It was further substantiated that self-efficacy has been considered as an acceptable construct within the vocational literature. While this study found similar results (self-efficacy as a strong and potential mediator variable) the results cannot be directly compared as their studies focused mainly on vocational and entrepreneurial elements.

5.5. Resilience as a Prospective Mediator Variable under Positive Psychology

Zhou et al. (2017) [65] examined resilience as an active mediating variable. In their study, they established a relationship between bullying/victimization and symptoms of depression. Their results revealed that resilience mediated both of the constructs (bullying/victimization) and depressive symptoms. Hence, their study demonstrated that resilience was an essential factor that mediated the relationship between bullying/victimization and childhood depression. Therefore, the vital role of resilience as an active mediating variable was established. This was similar to the findings in our study even though their study was conducted among Chinese children compared to the target population of college students in Nigeria for our study. Another study (Shin et al., 2012), which was related to organizational inducement and employee psychological resilience, coincided in the aspect of resilience with the present study; however, all other parts of their study were not congruent with the present research study.

Tugade and Fredrickson (2004) used the “Broaden and Build Theory” of positive emotion to examine the individual differences in psychological resilience from a problematic situation. Positive emotion was employed as a coping strategy. In their study, they concluded that positive emotion is related to a speedy recovery from negative situations. The study by Tugade et al. (2004) [66] also studied the same aspects as this study in terms of the theory and the use of resilience as a sub-construct. Similar studies among college students have also been conducted in other parts of the world [67,68].

5.6. Relationship between Study Skills and Examination Anxiety among Nigerian College Students

The findings based on research question number four demonstrated that the path analysis showed that study skills (SSK) had a significant and direct relationship with examination anxiety, and the relationship was positive. The research question also sought to examine the direct relationship between study skills and examination anxiety. It was found to be positive and significant. The direct relationship indicated that a higher level of positive study skills contributed to reduced examination anxiety. The same findings have been reported in other studies [69,70]. However, previous studies focused mostly on the relationship between examination anxiety and other research variables. In this study, the main aim was to determine if there is a relationship between study skills and examination anxiety. The findings were that there is a positive and significant relationship [71].

5.7. Relationship between Positive Psychological Strengths and Examination Anxiety among Nigerian College Students

Research question five demonstrated that there is a relationship between PPS and examination anxiety. The results from the path analysis showed that PPS is significantly and directly related to examination anxiety. The relationship is positive with a high path coefficient. The research question was designed to examine the direct relationship between PPS and examination anxiety. Consistently, the relationship between the two variables was found to be positive and significant. The direct relation indicated that the higher the PPS, the lower the level of examination anxiety. This study is in concordance with another published study [72]. However, previous studies focused mostly on the relationship between examination anxiety and other research variables. This study examined the relationship between study skills and examination anxiety and found a positive and significant relationship.

In this study, PPS was found to be a significant predictor of examination anxiety. This finding concurred with the Theory of Fredrickson (2001) [73]. Positive emotion is fast becoming more prominent in the field of PPS. As an example, the “Broaden and Build Theory” posits that positive activities are able to ‘broaden’ or enhance an individual, both emotionally and physically. It also helps to build the perseverance within oneself, and this subsequently translates into an innate resource and potential within the individual. In short, the theory supported the effort in enhancing the ability and capacity of the positive emotions of students (American Psychological Association, 2016).

6. Conclusions

Examination anxiety is a devastating condition that is connected with poor study skills and associated with worry. This could result in a setback to students who develop apprehension and tension, and the examination outcome makes the student suffer nervousness. Students are prone to adopt inadequate study skills, among a number of the skills employed by students, which perpetually leads the student to have a limited means of logical thinking. The sub-constructs under study skills: note taking skills, learning and remembering, organizing and planning time, and reading motives aided in establishing a relationship between study skills and examination anxiety as dependent variables. The analysis of the study skills showed that they are significantly related to examination anxiety. The direct relationship indicated that a higher level of effective study skills enhances the efficient outcome of study skills, and hence, reduces examination anxiety. Similarly, the results from the path analysis showed that PPS is significantly and directly related to examination anxiety. The relationship is positive with a path coefficient. Therefore, the null hypothesis was rejected. The mediation between positive psychological strengths (PPS) and examination anxiety is identified as effective and significant. Therefore, positive psychological strengths (PPS) acts as an effective mediator towards examination anxiety.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K. and M.A.G.; Methodology, A.B.A.L.; Resources, M.M. and Z.H.; A.B.M.K.; Validation, I.I., D.L.B.; Visualization, Z.H. and S.I.; Writing—review & editing, S.S., D.L.B., H.B., I.I., A.S.R. and S.A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Research Management Center (RMC), Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM), Johor bahru, Malaysia, grant number Q.J130000.2653.16J10.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ottaviani, C.; Borlimi, R.; Brighetti, G.; Caselli, G.; Favaretto, E.; Giardini, I.; Ruggiero, G.M. Worry as an adaptive avoidance strategy in healthy controls but not in pathological worriers. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2014, 93, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obosi, A.C.; Odusanya, A.A.; Tomoloju, O.P.; Olagoke, A. Influence of self efficacy, locus of control and gender on exam anxiety among utme, post utme and distance learning students in ibadan oyo state, Nigeria. Afr. J. Psychol. Stud. Soc. Issues 2018, 21, 62–72. [Google Scholar]

- Moravec, R.; Neitzel, T.; Stiller, M.; Hofmann, B.; Metz, D.; Bucher, M.; Raspe, C. First experiences with a combined usage of veno-arterial and veno-venous ECMO in therapy-refractory cardiogenic shock patients with cerebral hypoxemia. Perfusion 2014, 29, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olaitan, A.W. Socio-Demographic Factors That Determine the Usage of Mobile Phones in Rural Communities. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2018, 4, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, H.M. Investigating the Relationship between Understanding Vocabulary Meaning and Writing Ability. Master’s Thesis, Sudan University for Science and Technology, Khartoum, Sudan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Okolie, U.C.; Nweze, T. Assessment of Relationships between Students’ Counselling Needs, Class Levels and Locations: A Benue State Technical Colleges Study. J. Educ. Policy Entrep. Res. 2014, 1, 262–276. [Google Scholar]

- Igbokwe, B.A. Environmental Literacy Assessment: Assessing the Strength of an Environmental Education Program (EcoSchools) in Ontario Secondary Schools for Environmental Literacy Acquisition. 2016. Available online: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/5644 (accessed on 11 October 2019).

- Emaikwu, S.O. Aptitude testing in the 21ST century in Nigeria: The Basic Issues to Rivet. Res. J. Organ. Psychol. Educ. Stud. 2014, 3, 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Coker, A.O.; Coker, O.O.; Sanni, D. Psychometric properties of the 21-item Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21). Afr. Res. Rev. 2018, 12, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, I.R.; Razak, S.A.; Azhan, N.A.N. A review of current research in network forensic analysis. Int. J. Digit. Crime Forensics 2005, 5, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balduf, M. Underachievement among college students. J. Adv. Acad. 2009, 20, 274–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpan, J.P.; Beard, A. Jacksonville State University Assistive Technology and Mathematics Education. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2013, 2, 219–222. [Google Scholar]

- Olanipekun, B.F.; Tunde-Akintunde, T.Y.; Oyelade, O.J.; Adebisi, M.G.; Adenaya, T.A. Mathematical modelling of Thin-Layer Pineapple Drying. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2014, 39, 1431–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinsola, F.E.; Augustina, D.N. Test Anxiety, Depression and Academic Performance: Assessment and Management Using Relaxation and Cognitive Restructuring. Tech. Psychol. 2013, 4, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, P.; Gorji, Y.; Abedi, M.R. The Effect of Time Perspective Counselling on Career Control in High School Female Students of Esfahan city in academic year 2013–2014. UCT J. Manag. Account. Stud. 2012, 12, 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Aguinis, H.C.; Culpepper, S.; Pierce, C.A. Differential Prediction Generalization in College Admissions Testing; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, R.; Kuyken, W.; Taylor, F.S.; Rod, C.W.; Whalley, B.; Crane, C.; Guido, B.M.; Marloes, H.; Helen, M.; Susanne, S.; et al. Efficacy of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy in Prevention of Depressive Relapse. An Individual Patient Data Meta-analysis From Randomized Trials. JAMA Psychiatry 2016, 73, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwoke, D.; Ossai, O.; Obikwelu, C. Influence of Study Skills on Test Anxiety of Secondary School Students in Nsukka Urban, Enugu State, Nigeria. J. Educ. Pract. 2013, 4, 162–166. [Google Scholar]

- Enejoh, V.; Pharr, J.; Mavegam, B.O.; Olutola, A.; Karick, H.; Ezeanolue, E.E. Impact of self-esteem on risky sexual behaviors among Nigerian adolescents. AIDS Care 2016, 28, 672–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, S.; Gardner, J. Local knowledge in community-based approaches to medicinal plant conservation: Lessons from India. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2006, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwu, F.O.; Onyishi, I.E. Linking perceived organizational frustration to work engagement: The moderating roles of sense of calling and psychological meaningfulness. J. Career Assess. 2018, 26, 220–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.R. Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychol. Inq. 2002, 13, 249–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eseadi, C.; Obidoa, M.A.; Ogbuabor, S.E.; Ikechukwu-Ilomuanya, A.B. Effects of group-focused cognitive-behavioral coaching program on depressive symptoms in a sample of inmates in a Nigerian prison. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2018, 62, 1589–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheavens, J.S.; Feldman, D.B.; Gum, A.; Michael, S.T.; Snyder, C.R. Hope therapy in a community sample: A pilot investigation. Soc. Indic. Res. 2006, 77, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblom-Ylänne, S.; Saariaho, E.; Inkinen, M.; Haarala-Muhonen, A.; Hailikari, T. Academic procrastinators, strategic delayers and something betwixt and between: An interview study. Frontline Learn. Res. 2015, 3, 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Sui, Y.; Luthans, F.; Wang, D.; Wu, Y. Impact of authentic leadership on performance: Role of followers’ positive psychological capital and relational processes. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarıçoban, A.; Mohammadi, B.B. Academic Self-Efficacy and Prospective ELT Teachers’ Achievement. J. Lang. Linguist. Stud. 2016, 12, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Tong, L.; Takeuchi, R.; George, G. Corporate social responsibility: An overview and new research directions thematic issue on corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J.A.; White, B.; Viner, R.M.; Simmons, R.K. Bariatric surgery for obese children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 634–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friborg, O.; Martinsen, E.W.; Martinussen, M.; Kaiser, S.; Overgård, K.T.; Rosenvinge, J.H. Comorbidity of personality disorders in mood disorders: A meta-analytic review of 122 studies from 1988 to 2010. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 152, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waugh, C.E.; Koster, E.H. A resilience framework for promoting stable remission from depression. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 41, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.I. Spiritual Dimensions of Psychology; Shambhala Dragon Editions: Boulder, CO, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B. Flourishing under fire: Resilience as a prototype of challenged thriving. In Flourishing: Positive Psychology and the Life Well-Lived; Keyes, C.L.M., Haidt, J., Eds.; US American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 15–36. [Google Scholar]

- Regin, K.J.; Gadecka, W.; Kowalski, P.M.; Kowalski, I.M.; Gałkowski, T. Generational transfer of psychological resilience. Pol. Ann. Med. 2016, 23, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. Predictors of positive psychological strengths and subjective well-being among North Indian adolescents: Role of mentoring and educational encouragement. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 114, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchetti, D.; Blender, J.A. A multiple-levels-of-analysis perspective on resilience: Implications for the developing brain, neural plasticity, and preventive interventions. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1094, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huffman, J.C.; Beale, E.E.; Celano, C.M.; Beach, S.R.; Belcher, A.M.; Moore, S.V.; Suarez, L.; Motiwala, S.R.; Gandhi, P.U.; Gaggin, H.K.; et al. Effects of optimism and gratitude on physical activity, biomarkers, and readmissions after an acute coronary syndrome: The gratitude research in acute coronary events study. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2016, 9, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, T. The glass is half full half empty: A population-representative twin study testing if optimism and pessimism are distinct systems. J. Posit. Psychol. 2015, 10, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vera-Villarroel, P.; Valtierra, A.; Contreras, D. Affectivity as Mediator of the Relation between Optimism and Quality of Life in Men who have Sex with Men with HIV. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2016, 16, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segerstrom, S.C. Optimism and immunity: Do positive thoughts always lead to positive effects? Brain Behav. Immun. 2016, 19, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todesco, P.; Hillman, S.B. Risk perception: Unrealistic optimism or realistic expectancy. Psychol. Rep. 1999, 84, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammirati, R.J.; Lamis, D.A.; Campos, P.E.; Farber, E.W. Optimism, well-being, and perceived stigma in individuals living with HIV. AIDS Care 2015, 27, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheier, M.F.; Carver, C.S.; Bridges, M.W. Optimism, pessimism, and psychological well-being. In Optimism and Pessimism: Implications for Theory, Research, and Practice; Chang, E.C., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; pp. 189–216. [Google Scholar]

- Schwaba, T.; Robins, R.W.; Sanghavi, P.H.; Bleidorn, W. Optimism Development Across Adulthood and Associations With Positive and Negative Life Events. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2019, 10, 1092–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, A.J.; Buro, K. Other-oriented hope: Initial evidence of its nomological net. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 106, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satici, S.A. Psychological vulnerability, resilience, and subjective well-being: The mediating role of hope. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2016, 102, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, R.; Satici, S.A.; Akin, A. Mediating effect of Facebook® addiction on the relationship between subjective vitality and subjective happiness. Psychol. Rep. 2013, 113, 948–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottrell, S. The Study Skills Handbook; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.D. Test Anxiety Theory, Assessment and Treatment; Taylor and Francis: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M.; Avolio, B.J. Psychological Capital: Developing the Human Competitive Edge; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Oades, L.G. Wellbeing Literacy: The missing link in positive education. In Future Directions in Well-Being; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 169–173. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A. Studies in Positive Psychology; UTM Publisher: Johor Bahru, Malaysia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Leiter, M.P. Where to go from here: Integration and future research on work engagement. In Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2010; pp. 181–196. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, B.; Ruston, D.; Kates, L.W.; Arnold, R.M.; Cohen, C.B.; Faber-Langendoen, K.; Rabow, M.W. Discussing religious and spiritual issues at the end of life: A practical guide for physicians. JAMA 2002, 287, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomas, T.; Ivtzan, I. Second wave positive psychology: Exploring the positive–negative dialectics of wellbeing. J. Happiness Stud. 2016, 17, 1753–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, S.J.; Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Zhang, Z. Psychological capital and employee performance: A latent growth modelling approach. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyukgoze-Kavas, A. Predicting career adaptability from positive psychological traits. Career Dev. Q. 2016, 64, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, A.R.; Polman, R.; Levy, A.R.; Taylor, J.; Cobley, S. Stressors, coping, and coping effectiveness: Gender, type of sport, and skill differences. J. Sports Sci. 2007, 25, 1521–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive Psychology: An Introduction. In Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherland, 2014; pp. 279–298. [Google Scholar]

- Yee, C.M.; Mathis, K.I.; Sun, J.C.; Sholty, G.L.; Lang, P.J.; Bachman, P.; Williams, T.J.; Bearden, C.E.; Cannon, T.D.; Green, M.F.; et al. Integrity of emotional and motivational states during the prodromal, first-episode, and chronic phases of schizophrenia. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2010, 19, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, K.; Sadaf, S.; Saeed, A.; Idrees, A. Relationship between Hope, Optimism and Life Satisfaction among Adolescents. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2018, 9, 1452–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardon, M.S.; Kirk, C.P. Entrepreneurial Passion as Mediator of the Self–Efficacy to Persistence Relationship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 1027–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandri, G.; Luengo Kanacri, B.P.; Eisenberg, N.; Zuffianò, A.; Milioni, M.; Vecchione, M.; Caprara, G.V. Pro-sociality during the transition from late adolescence to young adulthood: The role of effortful control and ego-resiliency. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 40, 1451–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Douglass, R.P.; Autin, K.L. Career adaptability and academic satisfaction: Examining work volition and self-efficacy as mediators. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 90, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.K.; Liu, Q.Q.; Niu, G.F.; Sun, X.J.; Fan, C.Y. Bullying victimization and depression in Chinese children: A moderated mediation model of resilience and mindfulness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 104, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugade, M.M.; Fredrickson, B.L. Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 86, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feragen, K.B.; Stock, N.M. When there is more than a cleft: Psychological adjustment when a cleft is associated with an additional condition. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial J. 2014, 51, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulud, Z.A.; McCarthy, G. Caregiver burden among caregivers of individuals with severe mental illness: Testing the moderation and mediation models of resilience. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2017, 31, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putwain, D. Researching Academic Stress and Anxiety in Students: Some Methodological Considerations. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2017, 33, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segool, N.K.; Carlson, J.S.; Goforth, A.N.; Von Der Embse, N.; Barterian, J.A. Heightened test anxiety among young children: Elementary school students’ anxious responses to high-stakes testing. Psychol. Sch. 2013, 50, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumiris, A. The Effect of Using Teaching Methods on Student’s Achievement in Reading Comprehension; Unimed: Universitas Negeri Medan, Indonesia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.; Siraj, S.; Lau, P.L. Role of positive psychological strengths and big five personality traits in coping mechanism of University students. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Humanities, Society and Culture, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 4–6 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Psycnet. Apa. Org. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).