Patterns of Urban Park Use and Their Relationship to Factors of Quality: A Case Study of Tehran, Iran

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Benefits of Urban Parks

1.2. Negative Effect of Urban Parks (Crime and Safety)

1.3. Urban Park Spatial Equity, Accessibility

1.4. Urban Park Planning

1.5. Vegetation Quality in Urban Parks

2. Urban Planning and Green Space in the City of Tehran, Iran

2.1. History of Park Development in Tehran

2.2. Policies of the City of Tehran towards Public Green Space

3. Research Objective and Questions

- Why are some parks less used than others by some social groups?

- How well do the existing parks provide for the people of Tehran?

- What kinds of activities take place in the parks and what gaps in demand might there be?

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Research Strategy

4.2. Selection of the Sample Parks

4.3. Site Assessment

4.4. Site Physical Condition Assessment

- Accessibility to and within the park, whether easy to get there and then how easy to move around within the park (very easy to very difficult).

- The level of management and maintenance, meaning a combination of the overall management of the park and the maintenance of surfaces, vegetation, litter collection etc. (very well managed to very poorly maintained).

- The range of activities being pursued, whether formally provided for or spontaneously carried out (very busy to very quiet).

- Evidence of anti-social behaviour such as vandalism, litter, graffiti etc. (very much to very little).

- Permeability and movement: The degree of freedom of movement within the site using paths or crossing open areas (very free and permeable to very restricted).

- Inclusiveness: how well the design provides for all gender and age groups or groups with various disabilities, such as surfaces and seating etc. (very inclusive to very restricted).

- The quality of public areas: The overall functionality and suitability of facilities and outdoor furniture, public art, etc. (very good to very poor).

- Climate comfort: Environmental considerations: Areas exposed to sun, degree of shade, air currents and prevailing winds, vegetation, air and noise pollution.

- Lighting: Important in the evenings since this is a popular time for park use (well-lit to poorly lit with dark areas).

- Vegetation: The quality of the vegetation—its use in the design and its condition (very good to very poor).

- Flexibility: The capability of adaptation of a place for different activities (very flexibly to inflexible).

- Vitality: The overall sense of liveliness and popularity of the park—simultaneously the cause and effect of all other qualities (full of vitality to low in vitality).

- Safety and security: The overall sense of how safe and secure the site is, e.g., policing, surveillance, visibility etc. (very safe and secure to not very safe and secure.

4.5. Activity Assessment

5. Results

5.1. Site Assessment of the Sampled Parks and Their Relationship to Other Factors

5.2. Results of the Activity Assessments at Each Park

5.2.1. Amount of Use of Each Park by Population Type

5.2.2. Usage at Different Times of the Day

5.2.3. Amount of Use of Different Landscape in the Parks

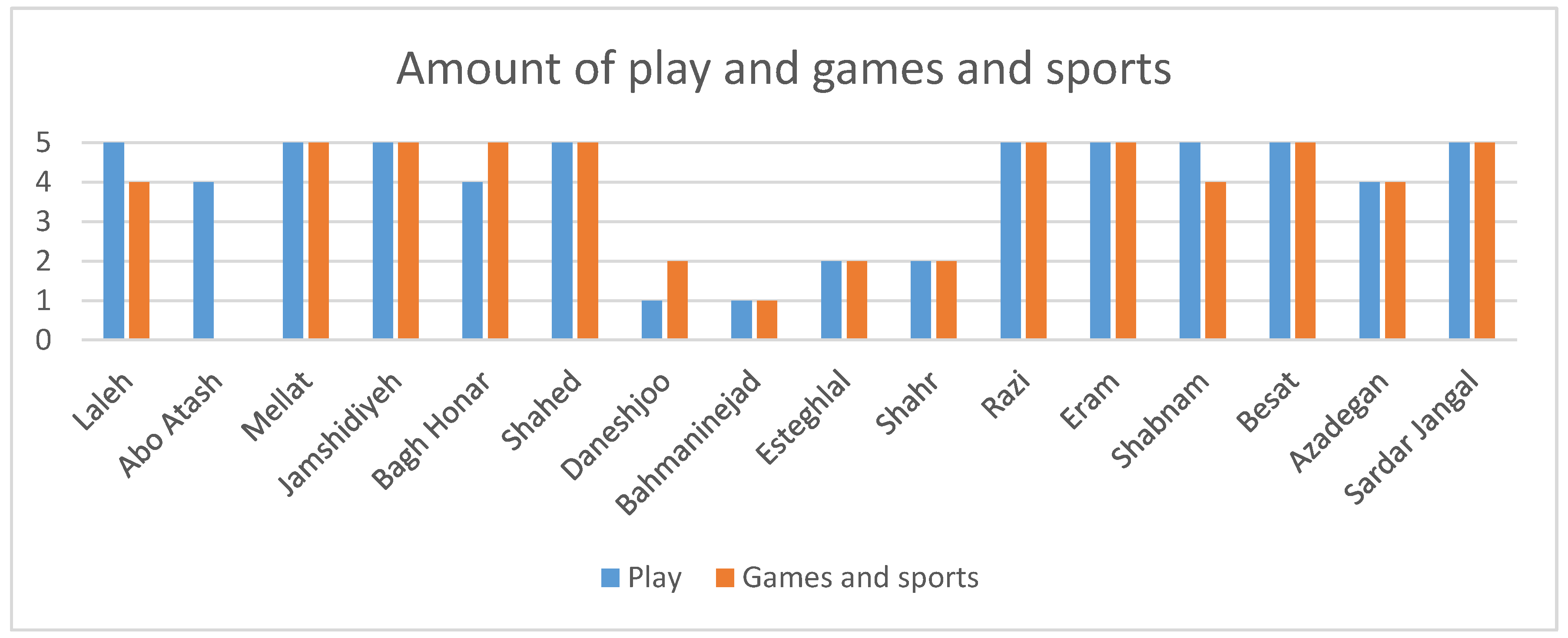

5.2.4. Amount of Different Activities in Each Park

5.2.5. Correlation between Time of Day and Use by Different Gender

5.2.6. Correlation between Activities and Landscape Elements

5.2.7. Correlation between Park Characteristics and Amount of Use by Gender/Children

5.2.8. Correlation between Socio-Economic Level and Park Characteristics

5.2.9. Correlation of Park Management and Maintenance with Type and Prevalence of Activities

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- Why are some parks less used than others by some social groups? We found that a combination of factors concerning the quality of the parks such as presence of facilities, how well maintained, well-lit and safe they, are has a lot to do with their level of use, especially by women. In some cases, the park happens to located in lower socio-economic class areas where anti-social activities seem to be prevalent but also religious practices which restrict some use, for example, by women undertaking physical activities such as running or cycling might be factors which we cannot know for certain but which deserve further attention.

- (2)

- How well do the existing parks provide for the needs of the people of Tehran? There is a wide range of recreational opportunities available across the sampled parks. Some parks with good layout and facilities are less well used because of, evidence of anti-social behaviour, poor maintenance and accessibility and a lower sense of safety and security. However, while men are well-catered for everywhere, women are found to be losing out in opportunities in a number of specific parks.

- (3)

- What kinds of activities take place in the parks and what gaps in demand might there be? We found that a wide range of activities are undertaken, ranging from informal recreation (walking, sitting, running, picnicking and children’s play as well as a lot of sport and some water-based recreation. In addition, amusements and entertainments are also available in many parks. However, because these are commercial, they are not freely available. The sports facilities are also separately managed and require a fee to use them or membership of a club. However, the other factor which affects demand is the gender difference in relation to certain types of activity and in part associated with social class.

7.1. Significance of the Research

7.2. Limitations of the Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Park. | Area (ha). | Main Features and Facilities. | Summary of Observation and Relationship of Use to Park Facilities. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laleh. | 28. | Street market, swimming pool, football field, green spaces and large open paved areas. | The main entrance features cultural and educational facilities which attract large numbers of people throughout the day. Once here visitors are invited to move into the main heart of the park where informal physical activities dominate. The swimming pool and other water areas also attract many people owing to the cooling effect of the water. Often numerous groups could be found here undertaking different social activities such as picnicking. Swimming in the pool is also very popular at all times in hotter weather. A market where vendors can sell refreshments and craft goods is also popular and helps to ensure that visitors spend a longer time in the park. The football field is managed separately, so is not freely available but the extensive open spaces result in many spontaneous activities taking place by different groups at all times. The flexibility of these spaces was demonstrated by the wide variety of uses during the observation period. |

| Abo Atash. | 6.5. | Water playgrounds, outdoor theatre, grass field, horse riding manage, nature Bridge, restaurants. | The water playgrounds, create a happy and lively atmosphere for children to play, accompanied by their parents. The gatherings and activities in this area are more frequent in the evening and the outdoor theatre is used at festival times, national celebrations a space for gathering. The park has many shady areas and people use the large open spaces for playing group sports and informal games in the mornings and evenings. There is an area with artificial grass specially designed for a zipline, which, although it takes up space, is hardly used. There is a tower at one of the main entrances of the park, allowing views over the whole park. This area can be crowded compared with other sections. The Nature Bridge or Tabi’at Bridge is a three-floor and multi-functional overpass connecting the two park sections and also includes various restaurants. While it is used all day the peak time is in the evening and at night. Some of the restaurants are very busy. |

| Mellat. | 34. | Lake, green spaces and large open paved areas; zoo; Island restaurant; Mellat cinematic Campus. | Mellat Park is one of the attractions of the city of Tehran. It contains a space for sculpture, which is popular for games and community sports during the day, but we can see individuals of different ages during evenings and nights. The lake is popular for recreational boating, often at night and in the evenings. The musical fountains play hourly at night, which draws a large crowd. The zoo is also popular. There are several restaurants next to the lake which attract people throughout the day, but more so at night. The large open area is flexible and suitable for sports and collective games in the early morning, evening and night. Mellat Cinematic Campus is an independent but integrated collection of cinemas and art galleries. In this park, green spaces and open spaces are interconnected organically, and are very flexible. People often come to the park in the evening, at night, and generally out of office hours, and all types of people in the community can be seen there. Different forms of activity take place at different times of the day. |

| Jamshidiyeh. | 69.0. | Waterfall and lake; outdoor amphitheatre: Green spaces and winding paths, restaurant. | This park is one of the most popular in the city, of Tehran in an area of higher social class. It is a peaceful place throughout the day and week, and despite its considerable size and difficulty of monitoring of the whole spaces security is good. The lake with its waterfall is one of the main attractions as it is scenically attractive and cool. The park is quiet during the day but very busy in the evenings at night. The park has two outdoor theatres which host some small gatherings and are usually not crowded, but when the park is crowded they are used for sitting by many people. The park is located in the hills to the north of the city and has a lot of steep paths which may deter some users of make some areas difficult to access. |

| BaghHonar. | 5.9. | Playgrounds, table tennis tables; Iranshahr concert hall and artists’ house; green spaces; large open paved areas; street market, café and restaurant. | The concert hall, art galleries, cinema and theatre attracts a large audience from around the city every day, especially from afternoon to midnight. This contrasts with the more local character of most of the visitors. The playgrounds and playing fields for team sports such as football and volleyball, ping pong tables function independently of the park. Due to its main theme, the park in its green spaces contains valuable statues and statues of Iranian artists. In fact, the park’s green space has become somewhat a beautiful garden of statue. |

| Shahed. | 3.2. | Playgrounds, open spaces. | The park is a very busy large-scale local park, due to its various qualities, including playgrounds, open spaces for the use of families. The high population of the surrounding areas lead to high levels of use. There are no special facilities so it caters for general recreation by people of all ages. |

| Daneshjoo. | 3.2. | Wide entrance, city theatre, green open spaces, children’s playground,. | Despite being small and local, this is frequently very crowded in places and at certain times. The theatre area is always full but the rest of the park is often empty due to the presence of anti-social people. The wide entrance of the park is the busiest part of the park because of the theatre. Evening performances lead to the peak time for visits being related to these hours. The children’s playground, located in the south eastern corner and closer to residential neighbourhoods, is popular with children living in the vicinity of the park and their peak time of visiting is in the evening when their parents are not at work. |

| Bahmaninejad. | 3.2. | Natural environment, children’s playgrounds. | The survey of this local park shows that it meets the needs of near neighbourhood residents. While small it is divided into two sections by an arterial road. This splits the main uses: The eastern part or the play and activities of children and parents and the western part is used for quiet and restful activities. It is very green and natural. |

| Esteghlal. | 1.3. | Neighbourhood park near several residential areas on the edge of the city; green areas, children’s playgrounds. | The park is a local park located on the edge of the city. Children use it despite a sense of poor security. In the evenings and after office hours it is popular with families and children During the rest of the day, adults and elderly people use it but a significant number of migrant workers (Afghan) use the park which also affects the sense of safety and security. |

| Shahr. | 25. | Aquarium, library, bird garden, artificial Lake, peace museum alongside green areas, open spaces and children’s play areas. | This park can be divided into two sections, the area with special facilities (aquarium, library, museum, bird garden) visited by specific people or groups from all over the city and the part functioning as a neighbourhood park for local low-income inhabitants. It has low numbers of regular users and this contributes to the feeling of insecurity identified here. |

| Razi. | 25.7. | Sports fields, Razi cultural centre, children’s play areas, amusement park, sports fields. | This park has three main segments of users: Those visiting the cultural centre, those using the sport facilities (both operated as separate units) and the rest of the park, including the boating lake. The general users come from nearby as the access is not good. The large spaces and sense of emptiness makes it feel unsafe. The boating lake is popular in the evenings and at night. The children’s play areas are also used in the evenings. |

| Eram. | 70.0. | Tehran amusement park, lake, zoo, green spaces. | Eram Zoo, the largest zoo in Iran, is popular during the week with student groups with families during the holidays and weekends. The park is always busy, the funfair being open until late and all kinds of activities are undertaken there. |

| Shabnam. | 0.8. | Wide green spaces, children’s play areas. | This park acts as a local neighbourhood park as it just features “normal” park facilities such as open green areas, path network, play areas etc. It is popular and well-used through much of the day by local residents, especially in the evenings. |

| Besat. | 53. | Amusement park, theatre, recreational lake, football fields, market, green open spaces, children’s play area. | This park is on the southern edge of the city and caters to local people but is also used by new immigrants as a temporary place to stay (squatting, informal camping) which affects the image and sense of security for other users. The population is generally of a lower socio-economic class. The amusement park, is open in the evenings and the outdoor theatre is run as a separate enterprise, as is the football field complex. The lake is the most popular area, with boating and fishing, and the market stalls also attract people in the evening, making it the busiest place in the park. |

| Azadegan. | 112. | Children’s play area, green open spaces, recreational lake. | This park, being some distance from the city centre is not busy in the week but more so at weekends and holidays. The playgrounds operate separately and the boating lake is also a popular attraction part of the park. The green open spaces are used for informal spontaneous activities. |

| Sardar Jangal. | 1.3. | Green open spaces, sports and football field, amusement park, lake, children’s playground. | The green spaces in this park also contain many mature shade-bearing trees which make it useable in the daytime, although the park is most popular in the evenings and at night. The sports equipment attracts sports enthusiasts during all day hours. Children, teenagers and young people also choose this environment for sport, fun, and sometimes friendly chat. The football field operates separately but is popular. |

References

- Wang, D.; Brown, G.; Liu, Y. The physical and non-physical factors that influence perceived access to urban parks. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 133, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pröbstl-Haider, U.; Haider, W.; Wirth, V.; Beardmore, B. Will climate change increase the attractiveness of summer destinations in the European Alps? A survey of German tourists. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2015, 11, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Schebella, M.F.; Weber, D. Using participatory GIS to measure physical activity and urban park benefits. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 121, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, J.; Wolch, J. Nature, race, and parks: Past research and future directions for geographic research. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2009, 33, 743–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, D.A.; McKenzie, T.L.; Sehgal, A.; Williamson, S.; Golinelli, D.; Lurie, N. Contribution of public parks to physical activity. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesura, A. The role of urban parks for the sustainable city. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2014, 68, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faizi, M. The Role of Urban Parks in a Metropolitan City, Faculty of Architecture and Urban Studies; Environmental sciences 12, Summer 2006; Iran University of Science and Technology: Tehran, Iran, 2006; pp. 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J.; Gemzoe, L. New City Spaces; Danish Architectural Press: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, T.; Mang, M.; Evans, G.W. Restorative effects of natural environment experiences. Environ. Behav. 1991, 23, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, R.; Lamit, H.; Khoshnava, S.M.; Rostami, R.; Rosley, M.S.F. Sustainablecities and the contribution of historical urban green spaces: A case study of historicalPersian gardens. Sustainability 2015, 7, 13290–13316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ulrich, R.S. Aesthetic and Affective Response to Natural Environment. In Behaviour and the Natural Environment; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1983; pp. 85–125. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, T.; Mendes, R.N.; Vasco, A. Recreational activities in urban parks: Spatial interactions among users. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2016, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshpour, Z.A.; Mahmoodpour, A. Exploring the people’s perception of urban public parks in Tehran. REAL CORP 2009: Cities 3.0, Sitges. 22–25 April 2009. Available online: http://www.corp.at (accessed on 26 January 2020).

- Maller, C.; Townsend, M.; St Leger, L.; Henderson-Wilson, C.; Pryor, A.; Prosser, L.; Moore, M. Healthy parks, healthy people: The health benefits of contact with nature in a park context. In The George Wright Forum; George Wright Society: Hancock, MI, USA; Volume 26, pp. 51–83.

- Bendíková, E. Lifestyle, physical and sports education and health benefits of physical activity. Eur. Res. Ser. A 2014, 69, 343–348. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, R.E.; Anderson, L.E.; Pettengill, P. Managing Outdoor Recreation: Case Studies in the National Parks; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vasco, A.R.A. Caracterização dos Utilizadores e dos Serviçosculturais do ParqueFlorestal de Monsanto (Characterisation and Utilisation of Cultural Services in Monsanto Forest Park) (Doctoral Dissertation); University of Lisbon: Lisbon, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, O.; Tratalos, J.A.; Armsworth, P.R.; Davies, R.G.; Fuller, R.A.; Johnson, P.; Gaston, K.J. Who benefits from access to green space? A case study from Sheffield, UK. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 83, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, K.; Auld, C. Leisure, public space and quality of life in the urban environment. Urban Policy Res. 2003, 21, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wekerle, G.R.; Whitzman, C. Safe cities: Guidelines for Planning, Design, and Management; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1995; p. 206. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, C.C.; Francis, C. (Eds.) People Places: Design Guidelines for Urban Open Space; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, R.M.; Farrall, S. Gender, socially desirable responding and the fear of crime: Are women really more anxious about crime? Br. J. Criminol. 2004, 45, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hami, A.; Bin Maulan, S.; Mariapam, M.; Malekizadeh, M. The relationship between landscape planting patterns and perceived safety in urban parks in Tabriz, Iran. Afr. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 8, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cisneros, H.G. Defensible Space: Deterring Crime and Building Community; Urban Institute, Department of Housing and Urban Development: Washington, DC, USA, 1995.

- Cozens, P.M.; Saville, G.; Hillier, D. Crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED): A review and modern bibliography. Prop. Manag. 2005, 23, 328–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McAllister, D.M. An empirical analysis of the spatial behaviour of urban public recreation activity. Geogr. Anal. 1977, 9, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoyer-Tomic, K.E.; Hewko, J.N.; Hodgson, M.J. Spatial accessibility and equity of playgrounds in Edmonton, Canada. Can. Geogr./Le GéographeCanadien 2004, 48, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, G. Designing for Gender Equality in the Developing Context: Developing a Gender-Integrated Design Process to Support Designers’ Seeing, Process, and Space Making (Doctoral dissertation); ProQuest Dissertations and Theses (PQDT): Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Penalosa, G.; Pearson, L.J. How to move from talking to doing. In Resilient Sustainable Cities; Pearson, L., Newton, P., Roberts, P., Eds.; Routledge in association with GSE Research: Abingdon, UK, 2014; Volume 234, pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Ramon, M.D.; Ortiz, A.; Prats, M. Urban planning, gender and the use of public space in a peripheral neighbourhood of Barcelona. Cities 2004, 21, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawardena, K.R.; Wells, M.J.; Kershaw, T. Utilising green and bluespace to mitigate the urban heat island intensity. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 584–585, 1040–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodoudi, S.; Shahmohamadi, P.; Vollack, K.; Kubasch, V.; Che-An, A.I. Mitigating the Urban Heat island in the Megacity Tehran. Adv. Meteorol. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, F.; Valcuende, M.; Matzarakis, A.; Canel, J. Design of natural elements in open spaces in cities with a Mediterranean, conditions for comfort and urban ecology; Environmental Science and Pollution Research, Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 25(26), pp. 26643–26652. [Google Scholar]

- Puliafita, S.E.; Bohaca, F.R.; Allende, D.G.; Fernandez, R. Green Areas and Microscale Thermal Comfort in Arid Environments: A Case Study in Mendoza, Argentina. Atmos. Clim. Sci. 2013, 3, 372–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoyle, H.; Hitchmough, J.; Jorgensen, A. All about the ‘wow factor’? The relationships between aesthetics, restorative effect and perceived biodiversity in designed urbanplanting. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 164, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruani, T.; Amit-Cohen, I. Open space planning models: A review of approaches and methods. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 81, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faryadi, S.; Taheri, S. Interconnections of urban green spaces and environmental quality of Tehran. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2009, 3, 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamadi, S.; Hossienzadehdalir, K.; Norozisani, P. Evaluating Impact of Land Use Type on the Formation of Crime centers; A Case Study: Crime Theft-Related in Tabriz. J. Urban Res. Plan. 2017, 8, 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Tehran Parks and Green Space Organization. Tehran Green Space Plan. City of Tehran; Tehran Parks and Green Space Organization: Tehran, Estonia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bahrini, F.; Bell, S.; Mokhtarzadeh, S. The relationship between the distribution and use patterns of parks and their spatial accessibility at the city level: A case study from Tehran, Iran. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 27, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Department for Social and Cultural Studies. Typology (Clustering) of Neighbourhoods in Tehran; Department for Social and Cultural Studies: Tehran, Estonia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Golkar, K. Theories of urban design, typological analysis. J. Res. Arch. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Aminzadeh, B. Perceptions of Nature Contact in Islamic Cities; Sofeh Publishers: Tehran, Iran, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Khosravaninezhad, S.; Abaszadeh, Z.; Karimzadeh, F.; Zadehbagheri, P. Parks and an Analysis of their Role in Improving the Quality of Urban Life, Using Seeking-Escaping Model; Case Study: Tehran Urban Parks, Estonia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lotfi, S.; Koohsari, M.J. Measuring objective accessibility to neighbourhood facilities in the city (A case study: Zone 6 in Tehran, Iran). Cities 2009, 26, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrini, F.; Bell, S. Use of Public Parks in an Islamic Country in Transition: A Case Study of the Islamic Republic of Iran. ECLAS Conference Proceedings “Landscapes in Flux”; Estonian University of Life Sciences: Tartu, Estonia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. 2015 Global Risks 2015: Part 2: Risks in Focus: 2.3 City Limits: The Risks of Rapid and Unplanned Urbanization in Developing Countries. Available online: https://reports.weforum.org/global-risks-2015/part-2-risks-in-focus/2-3-city-limits-the-risks-of-rapid-and-unplanned-urbanization-in-developing-countries/ (accessed on 26 January 2020).

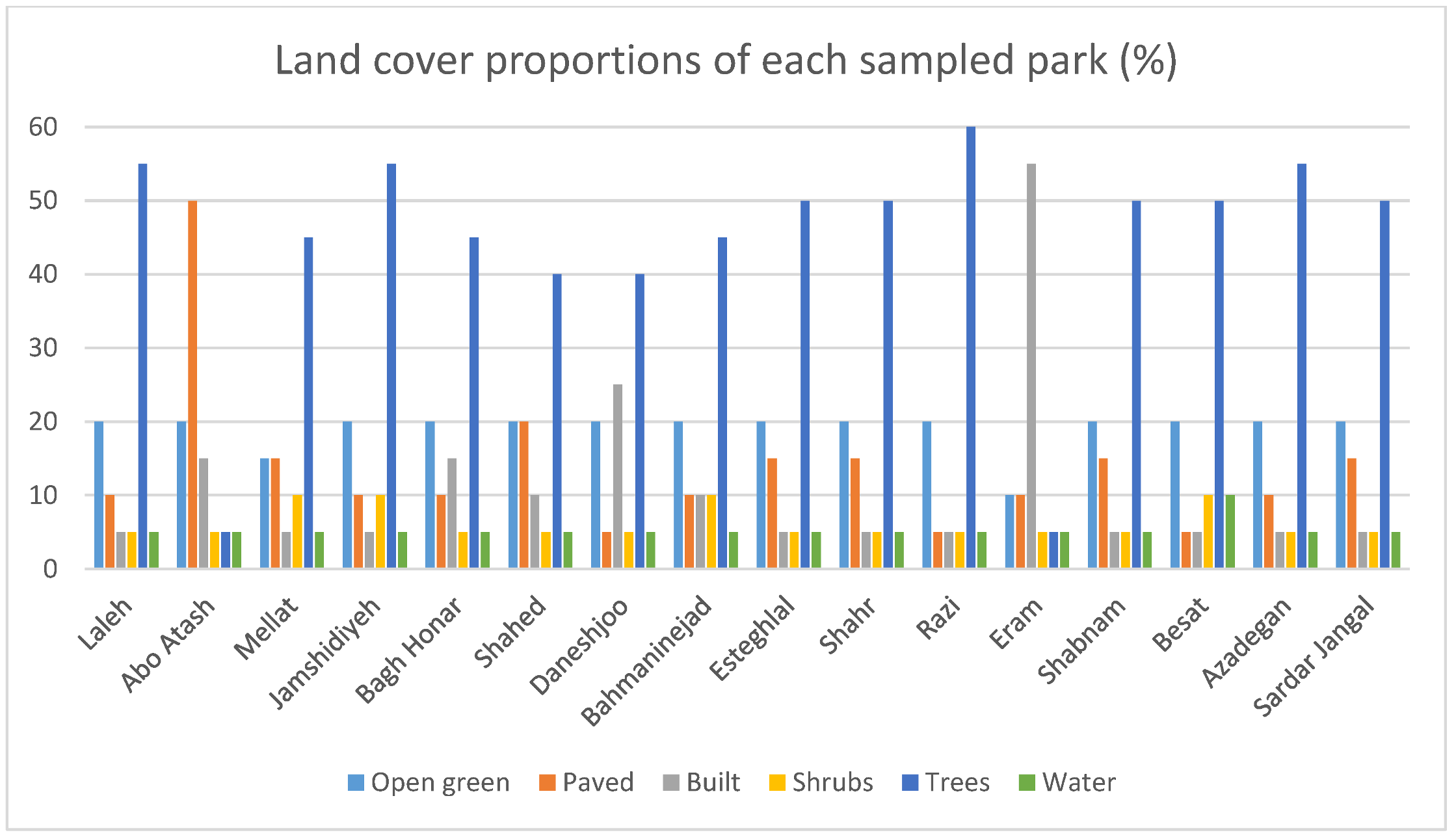

| Park Name | Socio-Economic Cluster | Year of Foundation | Total Area (ha) | Park Type and Main Facilities | Main Features of the Design, Main Trees Used and Estimated Proportions of Land Cover |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laleh | 10 | 1967 | 28.0 | A destination park with different and flexible areas for many activities | This park is well endowed with trees and contains some Japanese inspired sections. Types of trees: silver cedar, sycamore, oak, ginkgo, siddalashjar, acacia, maple, mulberry, bamboo, cedar, palm, elm, poplar, barberry. |

| Abo Atash | 10 | 1999 | 6.5 | A destination park with many recreational and commercial elements | This park includes many elements including a wide range of rocks and much use of concrete It has low green cover. Types of trees: cypress, sycamore. |

| Mellat | 9 | 1997 | 34.0 | A destination park with a lake and many recreational facilities | The design is informal and in a style based on English parks. It is well-endowed with many different trees (120 types) including: Guelder rose, Tabrizi cedar, ash, yucca, plane, weeping willow, acacia, pine, elm, poplar, cypress. |

| Jamshidiyeh | 9 | 1978 | 69.0 | A destination park with lake, restaurant and open-air amphitheatre | The design of this park is in the traditional Iranian garden style with many trees. Types of trees: apricot, pear, cherry, weeping willow, black maple, ash. |

| Bagh Honar | 8 | 1998 | 5.9 | A destination park with many facilities and also hosting the Iranian Artist’s forum. | The style of this park is a kind of eclectic fusion of English, Italian, French and Persian, and by combining these styles, a new art style has been created in the design of the park space. It is well-treed Types of trees include: cypress, elm, cedar, acacia, sycamore. |

| Shahed | 8 | 2002 | 3.2 | A local park with areas for ball games and children play | Design type: An informal style following free or natural forms (irregular and organic lines). Types of trees: acacia, cedar, elm, sycamore, sycamore, Egyptian silk, pine, magnolia, cedar, alder, yucca, barberry, eucalyptus, weeping willow. |

| Daneshjoo | 7 | 1968 | 3.2 | A destination park with a city theatre | The design of the park is formal and geometric in layout. Some of the types of trees: oak, olive, cypress, pine, plane, poplar, |

| Bahmaninejad | 7 | 2002 | 3.2 | A local park with ball games and children’s play | Design type: An informal style following free or natural forms (irregular and organic lines). Some of trees: pine, sycamore, cypress. |

| Esteghlal | 6 | 2008 | 1.3 | A local park with a children’s playground | Design type: using regular and organic lines. Some of trees: pine, sycamore, cypress. |

| Shahr | 5 | 1961 | 25.0 | A destination park with a lake, library and peace museum | This park is designed in a mix of Persian and French styles. Some of trees: pine, sycamore, cypress, poplar. |

| Razi | 5 | 1998 | 25.7 | A local park with lakes, a skate park, areas for ball games and children’s recreational centre | Type of style: no specific style, very eclectic. It is well-treed. Types of trees include: acacia, sycamore, silver cedar, evergreen oak, ice flower, pine, cedar, apricot olive, eucalyptus, maple, sparrow, poplar, orchard, Tabrizi cedar, lilac, ash clove, ash, Judas tree, weeping willow. |

| Eram | 4 | 1972 | 70.0 | A destination park with different areas for a variety of activities and attractions | The design of this park has strong themes derived from Iranian literature, history, culture and indigenous art. Very low on tree cover Some of the trees: pine and sycamore. |

| Shabnam | 3 | 1996 | 0.8 | A local park with children play | This park is designed according to the concept of a traditional Iranian park. Some trees: a range of evergreen trees, sycamore. |

| Besat | 2 | 1994 | 53.0 | A destination park with amusements and commercial activities | The design of the park and the themed amusement elements is derived from Iranian culture. A larger water element is found here. Some of the trees: Judas tree, ash, poplar, elm, sycamore, cedar, alder, oak, acacia and pine. |

| Azadegan | 2 | 2006 | 112.0 | A destination park with flexible areas for different activities, a lake, ball game areas; popular with Afghan immigrants | This large park is designed in two styles one more formal and regular and one more organic and informal. It has 90 species of trees and shrubs, including broadleaf and coniferous, and 400 shrub species, the most common of which are eucalyptus, pine, mulberry, poplar, ash tree, weeping willow, olive, Tabriz, walnut, voglia, shamshad, sidalashjar, palm, alder, oak. |

| Sardar Jangal | 1 | 2008 | 1.3 | A local park with playground and women-only exercise area, | This park is designed according to the concepts of a traditional Iranian park. Some of the trees: a range of evergreen trees, sycamore. |

| Park | Results of the Site Assessment | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Laleh |  | This park is in one of the oldest districts of the city and close to the most important student centres in Iran. It scores well for the variety of activities and lacks any antisocial problems; otherwise it is scores in the middle of the range and there are many aspects which could be improved. |

| Abo Atash |  | This park high scored highly in many areas, especially in the quality of the public areas, the level of maintenance, variety of activity and vitality, with correspondingly low levels of anti-social activity. The weaknesses were in the amount and quality of vegetation and the climate comfort – suggesting that there is insufficient shade which could limit the usability of parts of the park at certain times of day. Other aspects were also satisfactory but could be improved. |

| Mellat |  | This park scores highly in many key attributes. The overall quality of the public areas is high and the maintenance, lack of antisocial activities, sense of security and variety of activities are all connected with making it a successful park. A weakness is the climate comfort – reflected in the low score for vegetation cover and quality. Other factors are adequate although they could be improved. This park is considered to be one of the main attractions of the city of Tehran. |

| Jamshidieh |  | This is a well-established popular park, located in the so-called uptown area of the city, where higher socio-economic classes live. It is free from antisocial activities, has good, mature vegetation and is one of the few parks with good lighting. It is well-maintained and generally scores fairly well on other dimensions. |

| Bagh Honar |  | This park is well-known because it includes a popular art centre in its territory. The level of the use is high, with a wide range of activities. While located in a low socio-economic level district, most of the visitors are of a higher, well-educated social class. It only scores highly for maintenance and vitality. It is free of anti-social activities. There are a number of areas for improvement. |

| Shahed |  | This is a well-maintained park with an absence of anti-social activities but otherwise scores in the middle of the range and has potential to be improved. |

| Daneshjoo |  | This park lies in a deprived area with a low population density but is also the site of a major city theatre. It has good accessibility and vitality but only moderate scores for everything else. Security is relatively poor for a place with an important theatre. |

| Bahmaninejad |  | This is a small-scale local park, and is very green. There is little antisocial activity present but maintenance is poor, as is lighting and access with a low sense of security as a result. |

| Esteghlal |  | This small, local park on local scale, remote from the main core of the city suffers from many problems, these being a combination of poor maintenance, poor accessibility, a high level of anti-social activity, poor spatial quality and thus a low sense of security. The vegetation is good here. |

| Shahr |  | This park is the first steps in converting an Iranian garden into a public park. It is located in the lower part of the city in an area of lower social class. The park has many problems, foremost being poor maintenance, a low sense of security and many antisocial activities. Lighting is also poor but the vegetation is very good and the climate comfort is better than in many other parks due to the shade provided by the trees. |

| Razi |  | This park has access problems owing to its distance from where people live. It has poor lighting and a degree of antisocial activity leading to a feeling of a lack of security. Most other aspects are middle of the range with only climate comfort being good. |

| Eram |  | This park contains Eram Zoo, the largest zoo in Iran, which is popular with large numbers of people both during the week and during holidays and weekends. It scores highly for vitality and variety of activities and has no anti-social activity problems. Otherwise it scores less well, especially for vegetation and rather poorly for climate comfort and the level of maintenance. |

| Shabnam |  | This is regarded as a small-scale local park and it scores poorly in many aspects. While antisocial activities are not significant, the low quality of maintenance and poor lighting mean it feels less secure. It is secure due to the presence of local people at different times of the day. The vegetation creates good shade but it is not very inclusive and has few opportunities for activities. It is in need of a major upgrade. |

| Besat |  | This is a regional park located adjacent to the southern boundary of the city and used by visitors from out of the city. It has good accessibility and rich vegetation but poor vitality, inadequate lighting and all other aspects fall in the middle of the range. |

| Azadegan |  | Azadegan Park in a low socio-economic, deprived district, despite its large size and its planning as a metropolitan parkland. The current activities in this park are fairly diverse, but is has poor access due to its location. The level of security is low and it is poorly maintained, has low levels of lighting, and quite a lot of antisocial activity. Vegetation is good and climate comfort is also good, due to the shade provided by the trees. |

| Sardar Jangal |  | This park is a local one with a children’s play area and also a women-only exercise area. It scores moderate to low for most of the factors except accessibility, which is very good. It is notably poor in vitality, quality of public areas and lighting |

| Accessibility to and within the Park | Level of Management and Maintenance | Range of activities | Evidence of Anti/Social Behaviour | Permeability and Movement | Inclusive- Ness | Quality of Public Areas | Climate Comfort | Lighting | Vegetation Quality | Flexibility | Safety and Security | Vitality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accessibility to and within the park | 1 | 0.690 ** | 0.429 | −0.245 | 0.257 | 0.43 | 0.131 | 0.159 | 0.517 * | −0.026 | 0.259 | 0.634 ** | 0.46 |

| . | 0.003 | 0.097 | 0.361 | 0.336 | 0.096 | 0.628 | 0.557 | 0.04 | 0.922 | 0.333 | 0.008 | 0.073 | |

| Level of management and maintenance | 0.690 ** | 1 | 0.745 ** | −0.600 * | 0.458 | 0.736 ** | 0.504 * | 0.25 | 0.753 ** | −0.298 | 0.456 | 0.894 ** | 0.802 ** |

| 0.003 | . | 0.001 | 0.014 | 0.074 | 0.001 | 0.047 | 0.35 | 0.001 | 0.262 | 0.076 | 0 | 0 | |

| Range of activities | 0.429 | 0.745 ** | 1 | −0.459 | 0.566 * | 0.852 ** | 0.459 | 0.012 | 0.673 ** | −0.558 * | 0.734 ** | 0.809 ** | 0.679 ** |

| 0.097 | 0.001 | . | 0.074 | 0.022 | 0 | 0.074 | 0.965 | 0.004 | 0.025 | 0.001 | 0 | 0.004 | |

| Evidence of anti/social behaviour | −0.245 | −0.600 * | −0.459 | 1 | −0.378 | −0.454 | −0.572 * | 0.293 | −0.698 ** | 0.304 | −0.118 | −0.636 ** | −0.489 |

| 0.361 | 0.014 | 0.074 | . | 0.149 | 0.077 | 0.021 | 0.271 | 0.003 | 0.252 | 0.664 | 0.008 | 0.055 | |

| Permeability and movement | 0.257 | 0.458 | 0.566 * | −0.378 | 1 | 0.807 ** | 0.666 ** | 0.355 | 0.519 * | −0.358 | 0.630 ** | 0.543 * | 0.597 * |

| 0.336 | 0.074 | 0.022 | 0.149 | . | 0 | 0.005 | 0.177 | 0.039 | 0.173 | 0.009 | 0.03 | 0.015 | |

| Inclusive-ness | 0.43 | 0.736 ** | 0.852 ** | −0.454 | 0.807 ** | 1 | 0.662 ** | 0.327 | 0.717 ** | −0.492 | 0.750 ** | 0.792 ** | 0.776 ** |

| 0.096 | 0.001 | 0 | 0.077 | 0 | . | 0.005 | 0.217 | 0.002 | 0.053 | 0.001 | 0 | 0 | |

| Quality of public areas | 0.131 | 0.504 * | 0.459 | −0.572 * | 0.666 ** | 0.662 ** | 1 | 0.346 | 0.629 ** | −0.22 | 0.588 * | 0.574 * | 0.643 ** |

| 0.628 | 0.047 | 0.074 | 0.021 | 0.005 | 0.005 | . | 0.189 | 0.009 | 0.414 | 0.017 | 0.02 | 0.007 | |

| Climate comfort | 0.159 | 0.25 | 0.012 | 0.293 | 0.355 | 0.327 | 0.346 | 1 | −0.075 | 0.313 | 0.405 | 0.135 | 0.245 |

| 0.557 | 0.35 | 0.965 | 0.271 | 0.177 | 0.217 | 0.189 | . | 0.783 | 0.238 | 0.119 | 0.617 | 0.36 | |

| Lighting | 0.517 * | 0.753 ** | 0.673 ** | −0.698 ** | 0.519 * | 0.717 ** | 0.629 ** | −0.075 | 1 | −0.446 | 0.349 | 0.834 ** | 0.840 ** |

| 0.04 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.039 | 0.002 | 0.009 | 0.783 | . | 0.084 | 0.185 | 0 | 0 | |

| Vegetation quality | −0.026 | −0.298 | −0.558 * | 0.304 | −0.358 | −0.492 | −0.22 | 0.313 | −0.446 | 1 | −0.371 | −0.487 | −0.452 |

| 0.922 | 0.262 | 0.025 | 0.252 | 0.173 | 0.053 | 0.414 | 0.238 | 0.084 | . | 0.157 | 0.056 | 0.079 | |

| Flexibility | 0.259 | 0.456 | 0.734 ** | −0.118 | 0.630 ** | 0.750 ** | 0.588 * | 0.405 | 0.349 | −0.371 | 1 | 0.578 * | 0.535 * |

| 0.333 | 0.076 | 0.001 | 0.664 | 0.009 | 0.001 | 0.017 | 0.119 | 0.185 | 0.157 | . | 0.019 | 0.033 | |

| Safety and security | 0.634 ** | 0.894 ** | 0.809 ** | −0.636 ** | 0.543 * | 0.792 ** | 0.574 * | 0.135 | 0.834 ** | −0.487 | 0.578 * | 1 | 0.803 ** |

| 0.008 | 0 | 0 | 0.008 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.617 | 0 | 0.056 | 0.019 | . | 0 | |

| Vitality | 0.46 | 0.802 ** | 0.679 ** | −0.489 | 0.597 * | 0.776 ** | 0.643 ** | 0.245 | 0.840 ** | −0.452 | 0.535 * | 0.803 ** | 1 |

| 0.073 | 0 | 0.004 | 0.055 | 0.015 | 0 | 0.007 | 0.36 | 0 | 0.079 | 0.033 | 0 | . | |

| N | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| All Men | All Women | Children | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morning | Correlation Coefficient | 0.338 | 0.143 | 0.362 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.201 | 0.597 | 0.169 | |

| Midday | Correlation Coefficient | 0.559 * | 0.169 | 0.428 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.024 | 0.531 | 0.098 | |

| Afternoon | Correlation Coefficient | 0.558 * | 0.269 | 0.427 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.025 | 0.314 | 0.099 | |

| Evening | Correlation Coefficient | 0.224 | 0.166 | 0.257 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.043 | 0.558 | 0.038 | |

| Night | Correlation Coefficient | 0.486 | 0.123 | 0.35 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.056 | 0.651 | 0.184 | |

| N | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Paths | Surfaced Open Areas | Lawn | Shrubs | Trees | Water Features | Games Pitches | Children’s Play | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walking | Correlation Coefficient | 0.904 ** | 0.592 * | 0.373 | 0.555 * | 0.533 * | 0.654 ** | 0.476 | 0.169 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0 | 0.016 | 0.155 | 0.026 | 0.034 | 0.006 | 0.062 | 0.531 | |

| Standing | Correlation Coefficient | 0.514 * | 0.3 | 0 | 0.076 | −0.08 | 0.183 | 0.269 | 0.233 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.041 | 0.259 | 1 | 0.78 | 0.767 | 0.498 | 0.313 | 0.385 | |

| Cycling | Correlation Coefficient | 0.541 * | 0.196 | 0.45 | 0.301 | 0.45 | 0.364 | 0.46 | 0.181 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.031 | 0.468 | 0.08 | 0.258 | 0.08 | 0.166 | 0.073 | 0.503 | |

| Sitting | Correlation Coefficient | 0.654 ** | 0.395 | 0.234 | 0.618 * | 0.399 | 0.658 ** | 0.21 | 0.208 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.006 | 0.13 | 0.383 | 0.011 | 0.126 | 0.006 | 0.435 | 0.439 | |

| Jogging | Correlation Coefficient | 0.567 * | 0.567 * | 0.547 * | 0.532 * | 0.565 * | 0.358 | 0.569 * | −0.028 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.028 | 0.034 | 0.023 | 0.174 | 0.021 | 0.917 | |

| Picnicking | Correlation Coefficient | 0.576 * | 0.458 | 0.175 | 0.43 | 0.33 | 0.583 * | 0.444 | 0.204 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.019 | 0.074 | 0.517 | 0.096 | 0.211 | 0.018 | 0.085 | 0.449 | |

| Play | Correlation Coefficient | 0.335 | 0.713 ** | 0.42 | 0.398 | 0.539 * | 0.301 | 0.717 ** | 0.146 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.205 | 0.002 | 0.105 | 0.126 | 0.031 | 0.257 | 0.002 | 0.589 | |

| Games and sports | Correlation Coefficient | 0.566 * | 0.821 ** | 0.408 | 0.552 * | 0.417 | 0.349 | 0.802 ** | 0.371 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.028 | 0 | 0.131 | 0.033 | 0.122 | 0.202 | 0 | 0.174 | |

| Water play | Correlation Coefficient | 0.324 | 0.217 | −0.29 | −0.29 | −0.32 | 0.089 | −0.115 | 0.087 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.221 | 0.42 | 0.272 | 0.268 | 0.223 | 0.744 | 0.672 | 0.75 | |

| Horse riding | Correlation Coefficient | 0.324 | 0.217 | −0.29 | −0.29 | −0.32 | 0.089 | −0.115 | 0.087 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.221 | 0.42 | 0.272 | 0.268 | 0.223 | 0.744 | 0.672 | 0.75 | |

| N | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| All Men | All Women | Children | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of management and maintenance | Correlation Coefficient | 0.756 ** | 0.510 * | 0.825 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.001 | 0.043 | 0 | |

| Evidence of anti/social behaviour | Correlation Coefficient | −0.29 | −0.715 ** | −0.294 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.276 | 0.002 | 0.27 | |

| Inclusiveness | Correlation Coefficient | 0.547 * | 0.476 | 0.647 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.028 | 0.062 | 0.007 | |

| Lighting | Correlation Coefficient | 0.615 * | 0.608 * | 0.511 * |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.043 | |

| Safety and security | Correlation Coefficient | 0.716 ** | 0.700 ** | 0.825 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0 | |

| N | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Accessibility to and within the Park | Level of Management and Maintenance | Range of Activities | Evidence of Anti-Social Behaviour | Permeability and Movement | Inclusiveness | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-economic level | Correlation Coefficient | 0.496 | 0.752 ** | 0.605 * | −0.682 ** | 0.322 | 0.579 * |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.051 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.004 | 0.223 | 0.019 | |

| N | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | |

| Accessibility to and within the Park | Climate Comfort | Lighting | Vegetation Quality | Flexibility | Vitality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-economic level | Correlation Coefficient | 0.496 | −0.132 | 0.733 ** | −0.399 | 0.228 | 0.624 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.051 | 0.625 | 0.001 | 0.126 | 0.397 | 0.01 | |

| N | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | |

| Walking | Standing | Cycling | Sitting | Jogging | Picnicking | Play | Games and Sports | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of management and maintenance | Correlation Coefficient | 0.713 ** | 0.531 * | 0.582 * | 0.619 * | 0.305 | 0.647 ** | 0.222 | 0.523 * |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.002 | 0.034 | 0.018 | 0.011 | 0.251 | 0.007 | 0.408 | 0.045 | |

| N | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 15 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bahriny, F.; Bell, S. Patterns of Urban Park Use and Their Relationship to Factors of Quality: A Case Study of Tehran, Iran. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1560. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041560

Bahriny F, Bell S. Patterns of Urban Park Use and Their Relationship to Factors of Quality: A Case Study of Tehran, Iran. Sustainability. 2020; 12(4):1560. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041560

Chicago/Turabian StyleBahriny, Fariba, and Simon Bell. 2020. "Patterns of Urban Park Use and Their Relationship to Factors of Quality: A Case Study of Tehran, Iran" Sustainability 12, no. 4: 1560. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041560