To accomplish these aims, landscape design, the discipline that provides greenway design criteria, planting solutions and choices for materials construction, borrows the theoretical framework and methodology to assess the effect of different planting solutions on individual preferences and perceived restoration from environmental psychology, a discipline whose purpose is to understand the complex relationships between people and the environments around them.

2.1. Environmental Preference and Restorative Experiences

Environmental perception is not a passive process of registration but an active process of interaction between the individual and the environment. Humans’ eyes and brains have evolved in order to extract from the natural world a sensible order that is crucial for survival [

26], and to recognize certain patterns of stimuli in the environment that satisfy the biological need for comprehension and exploration and offer the opportunity for relief from stress and mental fatigue [

27]. For this reason, human beings prefer natural environments or environments with natural attributes, namely those environments that give positive emotions and moods. In this regard, the Environmental Preference Model [

28] identifies the predictors of environmental preference in four physical characteristics: coherence, complexity, legibility and mystery, which are the result of an evolutionary process in terms of humans’ adaptation to the environment. The more the environment displays the right combination of predictors, the more it is preferred, because it meets the requirements of understanding and exploration [

27].

Natural environments are highly preferred because they are perceived as more coherent, less complex, more legible and having the right level of mystery compared to built/artificial environments. Natural environments are preferred because they are also perceived as more restorative than built/artificial environments. Natural settings which allow positive changes in physiological activity levels and in behaviour and cognitive functioning, and more positively-tone emotional states are called “restorative” [

28].

In attention restoration theory (ART) [

29], voluntary attention is contrasted with involuntary attention. The former is effortful and can be tiring, whereas the latter is effortless and allows the attentional system to rest and recover. Unfortunately, everyday situations call for voluntary directed attention and the price paid is mental fatigue. It is important to find ways to restore the directed attention capacity; one way is exposure to natural environments. Attention can be categorized into two distinct functions: “bottom-up” attention, also known as stimulus-driven or exogenous, and “top-down” attention, also known as goal-driven or endogenous. In natural environments, mostly bottom-up involuntary attention is captured and people do not spend energy suppressing distracting stimuli [

30,

31]. In ART, this type of involuntary effortless attention has been referred to as fascination. Fascination is the most important characteristic of a restorative environment; thanks to fascination, directed attention can rest from mental/attentional fatigue and be restored. In addition, there are three other components that are likely to contribute to make an environment restorative: being-away (implies a setting that is distant either physically or conceptually from one’s everyday routine/environment), extent (the environment’s extension in time and space, whether the setting has sufficient coherence and scope to engage the mind and promote exploration), and compatibility (to what degree a setting fits and support one’s inclination or purpose). Natural settings not only are liberally endowed with all of them and hence assessed as more restorative than urban environments, but also are more preferred [

32,

33]. Usually natural settings are distinct from everyday environments of modern urban dwellers (being-away), are rich and coherent (ecosystems to observe, trails, paths for exploration), contain many sources of fascination (water, animals, foliage) and provide a wide range of compatible connection to the setting (hiking, observation, walking, peaceful meditation, cycling, etc.) [

34,

35].

The restoration process is a mixture of fascination and pleasure (i.e., preference); not only do settings that encourage fascination involve an important aesthetic component, but environmental preference and psychological restoration are also strongly related [

28,

33,

36].

The perception of restoration does not rely on naturalness only; on the contrary, it depends on a series of “sensorial semiotic aesthetic attributes” such as openness, mystery, complexity, order, vegetation, maintenance, style and perceived use [

37,

38]. Actually, fascination with nature derives from the quantity and quality of items displayed in Nature that people find appealing and pleasing. [

34]. The presence of trees is highly valuable for the urban environment [

39], and streetscapes where there are trees and spaces beneath them, i.e., flowering herbs in combination with trees, have the greatest effect on street preference [

40]. Studies of street-planting models [

41] showed preferences for combined types of vegetation, e.g., tall trees in combination with ground cover, or tall trees in combination with low trees. Street plantings create a safer and more comfortable environment for pedestrians and help to separate them from traffic, increasing the use of pedestrian strips [

42]. This effect was found more frequently for street plantings of a combined type, consisting of trees, shrubs and ground cover, than single formations consisting of only trees or shrubs. In brief, exposure to nature gives people an opportunity to recover cognitive resources and restore the optimal level of physiological activity and plays an important role in regulating emotions, as well as improving perceived well-being and promoting faster recovery from disease.

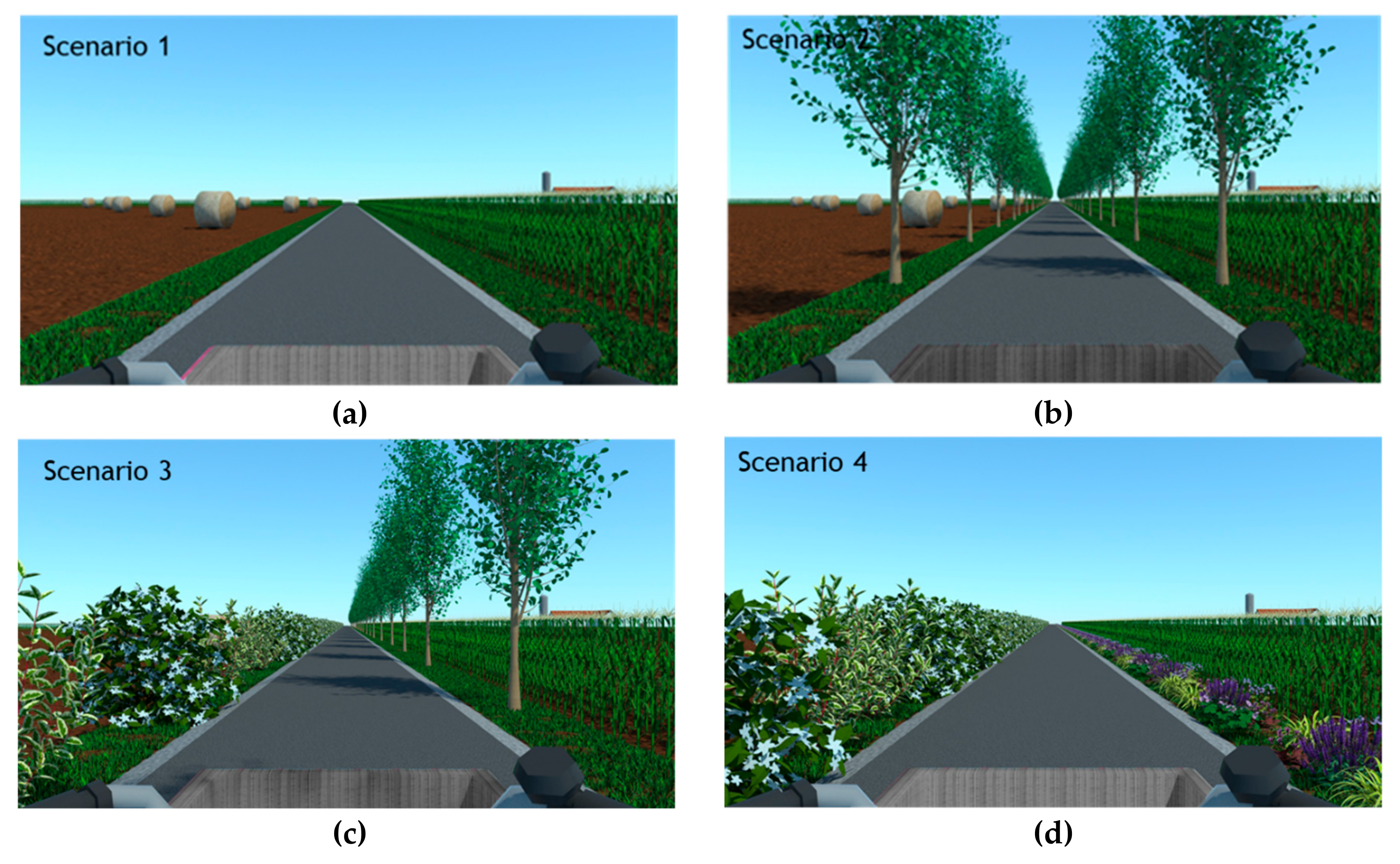

Vegetation offers natural fascinating distractions that have positive effects on one’s sense of control and privacy (which are displayed through “temporary being-away” or “temporary escape”), and encourages personal relationships and physical exercise (estrangement from routines means to move away from stress sources) [

43]. Greenways are more likely to promote activity than other green spaces because they serve a double purpose: they are transit corridors to reach school/work/recreational settings, etc., and destinations for leisure activity on their own [

44]. In both cases, well-planted greenways may not only increase the number of users but have a regenerative effect too. All types of vegetation contribute to the visual improvement of streets and paths and provide delineation of spaces, but this aspect lacks investigation as far as greenways are concerned. In this study we wanted to evaluate users’ preferences and perceived restorativeness of greenways: if greenways are appreciated and preference goes along with the perception of restorativeness, it means that they can help people in the process of restoration and recovery from stress.

2.2. Greenways: Experiencing a Landscape through Motion

Experiencing an environment by riding a bicycle is similar to the perception of a succession of images where both the subject and the items of the scene move within the visual field. In addition to what is done when driving, the cyclist needs to focus on the path, therefore the visual experience is not “complete” and the traveller fills knowledge gaps by imagining parts of the landscape he/she has missed seeing [

45]. The traveller clearly sees the foreground and might imagine the background. However, the outlined silhouette between sky and landscape is particularly important because it is the most dominant edge in a typical landscape image, and it has been found to attract a lot of the viewer’s attention. Along an unpaved rural greenway, pedestrian speed ranges from 3 km/h (families walking with children) to 10 km/h (runners), and bicycle speed ranges from 10 km/h (families with small children) to 35 km/h (adults in general) [

13]. When people travel on foot along a greenway, their landscape perception is similar to what they may have when walking in a green area [

46,

47], whereas when people travel by bicycle, their perception is more similar to the what they have when they drive. Pedestrians and cyclists cover greenways at different speeds and they a perceive the surrounding landscape in different ways.

Unfortunately, there are few studies showing the effect on users of greenway planting design [

25], while many studies show that roadside configurations have an effect on driver behaviour [

48]. Comparing the physiological responses of subjects who watched a video of driving through nature with those who watched a video of driving through more built-up environments, Parsons et al. [

49] found that the nature group had lower levels of stress and recovered more quickly from the stress they experienced.

Views of dense vegetation (vs. sparse and mixed) in fact enhanced drivers’ ability to tolerate frustration [

50]. In a survey assessing the scenic beauty of roadside vegetation in Northern England, the most preferred roadside vegetation type was a combination of grass and flowering herbs [

51].

According to Blumentrath and Tveit’s review [

52], three aspects need to be considered when addressing the design of a road to make it visually attractive: the road has to be seen (1) as an independent structure, (2) in relation to its surroundings and (3) in relation to the traveller’s movement. The following characteristics need to be considered:

Variety. This refers to landscape features. A variety of features and views from the road enhances the attractiveness and at the same time avoids monotony, reduces mental fatigue and enhances concentration [

53]. A variety of landscape over time is equally appreciated, e.g., vegetation colour and shape change with the seasons, day and night landscapes differ in shades and sounds, etc. A “good” landscape has a balance between unity and variety [

54].

Legibility. This is the degree to which a path is understandable for users [

55]. This quality is connected more to safety than attractiveness; uncertainty about the direction to follow and/or the distance to cover generates stress in users.

Aesthetics of flow, rhythm and balance. This refers to travel experience as a result of motion and space. Travel speed is a basic aspect of the aesthetics of flow. “The speed of human visual perception is estimated at around 25 frames per second” [

56]; considering a cycling speed of 25 km/h, this means cyclists perceive about 25 cm per frame. At this speed they are not able to perceive any planting elements that have a dimension smaller than 25 cm. Rhythm and balance maintain the continuity of the travel experience, easing mental fatigue. The aesthetics of flow includes “mystery” and “surprise,” which enhance road attractiveness [

52].

Orientation. This refers to the capacity of users to locate themselves in the landscape and understand progress in their movement. Disorientation causes anxiety, which in turn negatively affects the subjective perception of safety and attractiveness of the path experience in general. On the contrary, “orientation” enhances appreciation for the journey.

Greenways are public facilities and need to be designed addressing both safety and attractiveness for users, at the same time maintaining the integrity of the landscape environment [

14]. Toccolini et al. [

57] proposed a useful protocol to plan greenways at the regional level, made up of four phases: (1) analysis of the landscape resources, existing green trails and historical route networks; (2) assessment of each element; (3) composite assessment and (4) definition of the greenways plan. To start, a greenways intervention plan includes identifying the missing sections and lacking connections along the route and the elements of greatest interest. Interventions may be classified in relation to their type and may include improvements to both the constructive characteristics and the junctions. During the planning phase, it is necessary to select the greenway users; the selection of the target will help in the next phase when the design elements will be singled out. Once the route is planned and the users are identified, in phase two, the designer needs to more specifically define the characteristics of the greenway, such as sections and other geometric characteristics, surface materials, road crossings, signs, support facilities (e.g., parking areas, rest rooms, drinking fountains, benches, etc.) and planting materials [

14,

58,

59]. In particular, plant materials fill a number of roles in greenway design: they create a good microclimate for users [

14], enhance the ecological [

18] and visual [

26] value, and offer structures around which to organize functions [

60]. Plantings must not reduce visibility: users should have at least of 30 m of forward visibility. This is particularly important at approaches to intersections. When plant material is properly chosen, it has no impact on the pre-existing environment and can be inserted in tiny spaces. For these reasons and because they are inexpensive, trees and shrubs are usually planted along greenways because they fit perfectly in this kind of project. With respect to Blumentrath and Tveit’s criteria [

52], planting material is useful to enhance greenway variety: the number of species is vast, plants are different from one another and change every day and in every season, etc.; greenway legibility: trees and plants along the way support way-finding and can be used to separate different users, e.g., walkers from cyclists, cyclists from road traffic, etc.; greenway aesthetics of flow: plants with different characteristics, e.g., height, colour, etc., can be alternated to give rhythm; and greenway orientation: rows of trees, monumental trees in particular, are excellent landmarks.