Abstract

Research on the Malay cultural landscape in the Malay Archipelago is based on several factors, which include function, tradition, and the Malay culture. These factors are widely found in Malay literature, which plays a significant role in designing the landscape of Malay culture. Malay literature includes Old Malay manuscripts, Hikayat Melayu (Malay folktales), and Malay poetry, all of which are based on the beliefs, mindsets, and culture of the Malay community. These are demonstrated in a tangible or intangible manner through the environment of the traditional Malay lifestyle, inherent in Malay life values and in the symbolism of places. This review employed a document analysis to identify the elements and components of the Malay cultural landscape and its metaphorical aspects, as reflected in the aforementioned four types of Malay literature. Moreover, this review obtained information on the elements of the Malay cultural landscape that determine and explain the nature, function, and similarity of these aspects through symbolism in the landscape and culture of the Malays in Malaysia. Indirectly, this review proved the long existence of a systematic Malay cultural landscape throughout the Malay Archipelago that remains essential for future cultural sustainability. Finally, elements of the Malay landscape were identified, which could be applied as guidelines for designers in outlining a Malay cultural landscape.

1. Introduction

The purpose of this review is to identify and highlight the elements of the Malay cultural landscape as recorded in Malay literature, which consists of cultural and artistic values that portray Malay symbolism. Values on beliefs, ways of thinking, and culture have been the bases of the Malay cosmology. These values have been indirectly depicted in the designs, art, compositions, symbols, and functions within Malay literature. Similarly to the Malay cultural landscape, Malay literature is also fading away due to the social and perceptual changes in modern development. As stated by Mahmud [1], many written facts about the study of Malay history (such as the life of the Malay people, their nature, their traditions, and their customs) are recorded in Malay literature, but this information is only available in certain sources of Malay history, such as Old Malay manuscripts, Hikayat Melayu (Malay folktales), and Malay poetry. In general, these sources provide a brief overview of the Malay cultural environment and the use of landscape elements in the life of the Malay community. Landscape is defined as the environment—reviewed and interpreted through the imagination of people living in an area based on their nature, customs, and culture [2]. As stated by Liu et al. [3], landscape and culture are not only synonymous with natural surroundings, but also influence humans’ perceptions and behavior. Similarly, Ahmad et al. [4] noted that the environment around us is not a beautiful landscape unless it is interpreted by another person. For others, a landscape is a metaphysical way of life shaped by the views of an ethnic group, embodying the nature, customs, and traditions of a nation [5]. Whelan and Moore [6] argued that the landscape of human ecology is a cultural practice where each race delves into the process of distinguishing between nature and the environment.

The above statement attests to the fact that landscapes are closely linked to the natural, cultural, traditional, and customary significance of the human race, which also includes the Malays [7]. Within Malay literature, the elements of indirect values and symbolism can be ascertained through the perception of meaning, which is meant to be delivered either through culture or function [8]. According to Akmal [9], the Malay cultural landscape is a link between natural and man-made interpretations: he interpreted an old work of scholarship in an ancient Malay text entitled Kitab Sulalatus Salatin (the manuscript of the “Genealogy of Kings”). Abdullah [10] emphasized that in shaping the Malay cultural landscape, Malay culture and traditions are the driving forces between nature and men. If we delve deeper into the natural and cultural elements of a race, such as the Malays, we can see that Malay literature covers the broad components of a cultural landscape, which encompasses physical, social, and perceptual aspects. According to Ismail et al. [11], the cultural landscape of the Malays is a complex system that combines physical, social, and perceptual components into a comprehensive source of knowledge, beliefs, art, morals, explanations, laws, environments, customs, and behaviors that one needs to become part of the community. Hussain et al. [12] and Ahmad et al. [4] have also stated that every class of society in the world has its own component of cultural landscape, which creates a race’s distinguishable identity, culture, tradition, custom, and character.

The Malay world can be seen through Malay literature, which is filled with life, customs, traditions, cultures, and beliefs inherited from ancestors through generations [13,14]. Evidently, the cultural landscape of the Malay community’s living environment has been influenced by nature and its surrounding life [15]. Hence, the aim of this paper is to analyze specific sources from Malay literature and their connection to sustainability in the architecture of the Malay landscape. In this review paper, the authors began by revisiting some previous studies that overlapped with Malay literature and the architecture of the Malay landscape. The method started with the selection of three main Malay literary texts: Old Malay manuscripts (e.g., the Tajul Muluk and Sejarah Melayu), Hikayat Melayu (Malay folktales) (e.g., the Hikayat Hang Tuah), and Malay poetry (e.g., the Mak Inang, Kurik Kundi, and others). The selection of Malay literary texts was based on four main criteria describing an image of place, natural elements, culture, and Malay behavior. Thus, the authors collected all of the Malay literature documents from the Malaysia National Archive, Malay manuscripts, and journals. The analysis of the Malay literary texts was done using a textual content analysis. Therefore, it can be said that Malay literature has long been influenced by the surrounding environment through the lens of cultural factors, such as the physical, social, and perceptual roles in creating sustainable living.

2. Malay Literature

The main problem identified in this review was the lack of written materials from Malay literature that can serve as contextual references for the architecture of the Malay cultural landscape. According to Abdullah et al. [4] and Mahmud [1], many written accounts of Malay history are flawed in terms of documentation and information. Much of the information related to Malay history is only available in some historical sources, such as old manuscripts, poetry, and Hikayat (folktales) [15]. As such, these materials have been used as the main references and guidelines for the Malay community in living sustainably within their culture, nature, and environment [10]. The available sources provide brief overviews of the use of natural elements in the life of the Malay community.

2.1. Old Malay Manuscripts

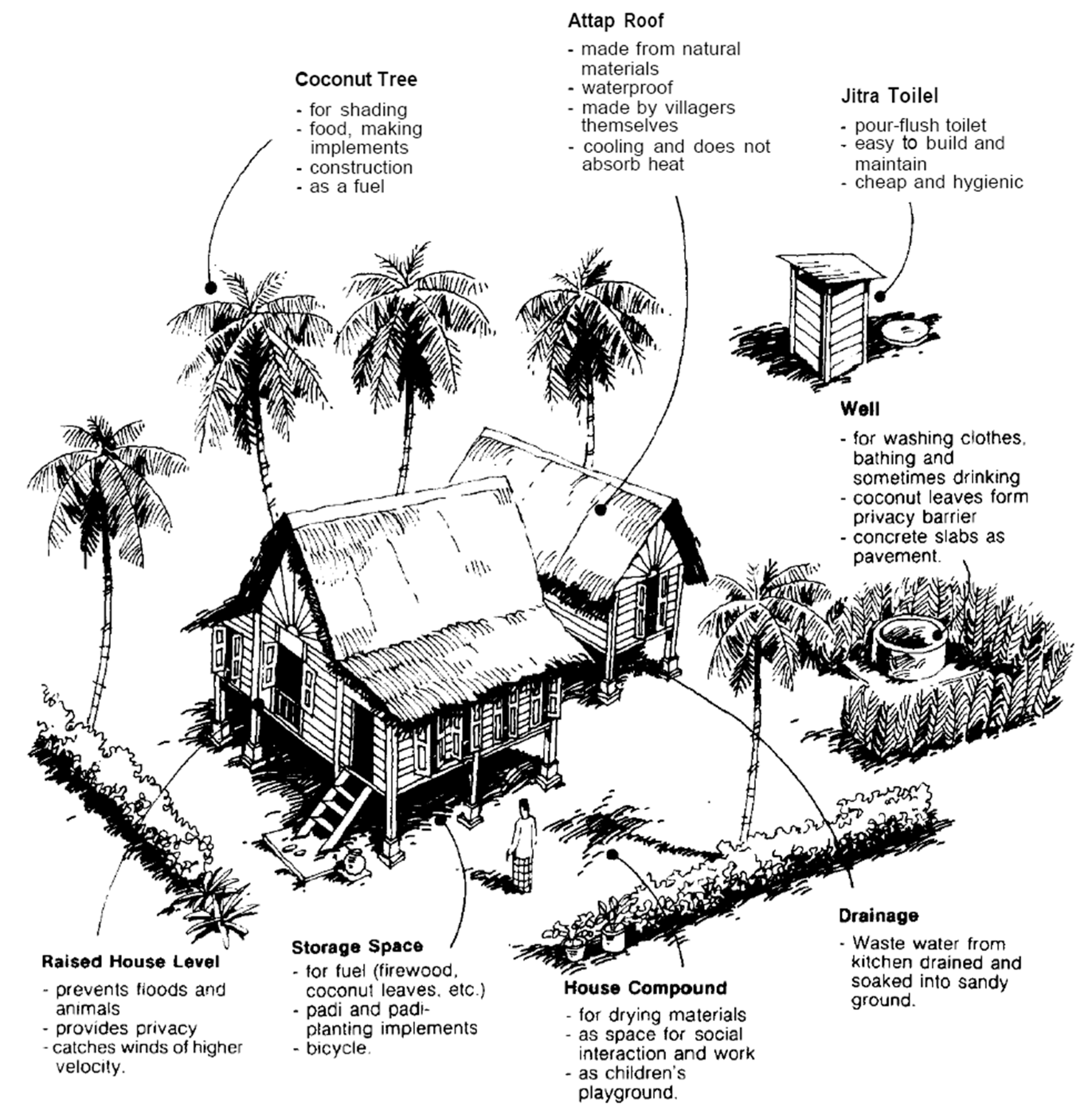

Traditionally, a manuscript refers to any handwritten document, such as the Kitab Tajul Muluk and Sejarah Melayu [16]. The old manuscripts referred to in this review consisted of various forms of written texts about the Malay culture and tradition, including Malay beliefs, perceptions, and architecture. These aspects are described in detail in the second edition of the Tajul Muluk, which was translated by Harun [17]. The customs of the Malay community, according to the Tajul Muluk, typically focus on the aforementioned aspects for guidelines in life. These guidelines are part of the belief in the intricacies of the Malay traditional residential construction system and the orientation of the layout of a residential area. The Tajul Muluk [15] and Sejarah Melayu [18] manuscripts describe the aspects of land selection, location, home orientation, and site selection in the construction of a residential area as well as in the layout of physical compartments around a house [19]. All of these principles in Malay manuscripts also reflect the customs, traditions, and beliefs of the traditional Malays. One example of such principles can be seen in the arrangement of physical elements in the external environment of the Malay house, also known as the Malay home garden. The Malay home garden is created not only for aesthetic purposes but also for presenting sustainable and functional aspects, such as food, beauty and decor, home protection, and medicinal value [7]. Figure 1 shows the space organization in a traditional Malay home garden, with plants such as coconut palm trees grown around the house for ornamental purposes, a food source, and even a security fence. Meanwhile, a traditional Malay house has its floor level constructed in an elevated position off the ground for the purpose of enduring floods and deterring wild animals. Furthermore, a raised house can also provide storage space, ensure privacy, and capture stronger winds for cooling and ventilation.

Figure 1.

The external environment of a traditional Malay home garden presents an authentic way to create sustainable living (source: Nasir [20]).

According to an old manuscript entitled the Adat Resam Melayu, [7] from the traditional Malay perspective, the orientation of the external environment of a Malay house is an important component that influences the character of the Malay landscape. The position of a Malay house’s entrance should face the rising sun, as the benefits of such practices have been ingrained among the Malays. Up to now, house space differentiation has been essential in ensuring that the space of a house is in line with the activities undertaken by the homeowner [17]. As indicated by Abdulah Sani et al. [4] (taken from an old text by Abdul Rahman Al-Ahmadi entitled the Petua Membina Rumah Melayu: Dari Sudut Etnis Antropologi), because sunrise emerges from the east and sets in the west, the afternoon sunlight is much hotter than the morning sunlight, which perhaps could harm the homeowner during certain weather conditions. The manuscript also does not encourage homeowners to orient their house’s entrance to the west, because sunset carries a superstition that the homeowner may experience bad health and a loss of wealth. However, Hussin et al. [21] stated that such a belief can be scientifically explained, since the setup protects a house from the full exposure of sunlight during daytime. Nowadays, very few Malays adhere to the rules and procedures mentioned above due to modernization and the change in the nature of society [22]. In addition to orientation, the old manuscript also explains the importance of purifying the surrounding areas to render the site suitable for residential use. According to Wan Muhammad et al. [23], purification in the Malay culture means not only physically clearing off wild bushes growing in the area, but also spiritually eradicating supernatural presences from selected sites. The Malays believe in the existence of supernatural realms, including good and bad spirits. The same practice is also mentioned in the Malay manuscript Kitab Tajul Muluk:

“Kitab Tajul Muluk, bab enam; jika bumi itu kata orang sangatlah keras syaitannya. Maka tatkala sudah atau dari bandarulahnya maka koreklah tanah sama tengah itu dipasak tengah itu dengan segeluk air berisi tujuh gemal macam jenis bunganya hingga sepilok, maka ambillah tanahnya maka kepal baik di masukan setahil emas mulia maka bacalah ayat pendinding.”

“The manuscript of Tajul Muluk, chapter six; should others say that the ground possesses powerful demons. Thus, dig a hole in the middle of the ground, and a handful of water infused with seven types of flowers is to be placed in it until filled, then grab the wet soil by a handful and mix it with a tael of precious gold, hence recite the protective verses.”[17]

The above excerpt explains that if Malays at a kampong (village) choose a new residential site and want the area to be constantly cool, quiet, and safe, the selected site needs to be cleansed and purified [23]. Other practices mentioned in the Malay manuscript of Kitab Tajul Muluk include the placement of an urn containing water infused with seven types of flowers, which is to be left for seven days and seven nights in the middle of the selected site. It mentions that “setahil emas mulia” (a tael of pure gold equivalent to 37.5 g) is to be placed inside the urn to signify or invite future wealth. A mantra is chanted before the urn is left in the middle of the site where the house will be built. The position of the urn will then be observed on the eighth day. According to Al-Ahmadi [8], if the urn does not change position on the eighth day, the site is suitable for building a house; however, if the urn shifts to a new position, the site is otherwise unsuitable for residential purposes. Such a notion is attributed to the belief that the land (where the urn’s position has shifted) is home to evil spirits. However, Aziz et al. [24] noted that from a modern perspective, any change in the urn’s position after the seventh day is most likely due to the topography of the land, which could suggest poor soil conditions, soft soil, or perhaps even the presence of an underground water movement. Logically, such a site is not suitable for building a house, whereas if the urn does not change position, the area’s soil is presumably compact and thus suitable for residential use. In ancient times, technological constraints compelled past Malay scholars to resort to using natural methods in determining the suitability of a land area for residential use. From a review of Old Malay manuscripts, it can be said that this practice was based on the beliefs, thoughts, culture, and social life of the Malays in the past. The nature-reliant culture of the past Malays was influential in both physical and metaphysical instances, indicating that the Malay world is a dynamic ecological system that links the creator, humans, and nature. Therefore, the relationship between the Malay cultural landscape and sustainability, as revealed by Malay literature, can be observed from the orientation of the house to the sun’s position, the air ventilation for the house and its compound, the arrangement of plants and hedges for security measures, the growing of edible plants for a food supply, the planting of fragrant flowers around a well for therapeutic effects, and the open space compound of the Malay house for community interactions (Figure 1). These design elements and arrangements describe a behavior indicating a sustainable lifestyle in the Malay culture.

2.2. Malay Folktales

In the Malay world, folktales are based on ancient Malay stories, which are transmitted by word of mouth from older generations to younger generations. Folktales are closely related to many storytelling conventions, which include fables, myths, and fairytales [25]. Every human society has its own folktales: these well-known stories are handed down from past generations and are a significant method of transmitting knowledge, information, and history [24]. In the Malay world, many types of Hikayat Melayu (Malay folktales) relay historical accounts, environments, experiences, and the culture of the Malay people [14]. Hikayat Melayu is a continuation of Malay history and its culture that is taken from various storylines. Malay folktales are generally quite consistent in their storylines and differ only in their linguistic details, such as vocabulary and sentence arrangement or structure [14]. Otherwise, the storylines are maintained [22]. According to Haji Salleh and Robson [26], Hikayat Hang Tuah is the greatest narrative of the Malay Archipelago and has always inspired a strong passion among its readers and audience. Hikayat Hang Tuah provides an impression of several natural elements that describe the settings and conditions of the place, the nature, the culture, and the mannerisms of the Malay community at that time. An excerpt from Hikayat Hang Tuah is shown below, while an example of the Malay home garden is shown in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

The Malay home garden is a part of its surrounding natural environment: it becomes an all-purpose space that gives a sense of pride to the homeowner (source: Zakri [28]).

“Maka laksamana pun sudahlah mandi lalu naik memungut bunga pada tepi kolam itu, pelbagai bunga-bungaan seorang sekendong…sudah makan buah-buahan itu, maka ia duduk mengarang bunga sambil bersenda, bernyanyi, berpantun dan berseloka berbagai-bagai ragamnya.”

“Thus, the admiral has taken a bath and picked flowers by the pool, a bunch of flowers he has gathered unto himself… upon having eaten the fruits, he sat down to weave the flowers while relaxing, singing, and reciting various types of poetry in a multitude of styles.”[27]

The above excerpt also suggests several physical elements in the Malay world, such as the function of a pool in softening the ambiance in the Malay landscape. The valuable elements in the excerpt above describe the importance of nature and environment in the Malay landscape, as determined by the perception of the meaning intended to be delivered in terms of either culture or function [10]. A pool area was used as a setting for human amusements such as flower weaving, singing, and other artistic pastimes. Shamsuddin [29] noted that human activities based on culture and the environment can create a unique effect in shaping the symbolism of a place. Hussain et al. [30] stated that a water element, such as a pool or a lake, can act as a softening agent for the atmosphere when it is located around a residential environment or used as a focal point, as the water element offers a dramatic and therapeutic effect to the area. Hussain et al. [30] also emphasized the function of flowers and fruit plants in the beautification of the Malay landscape. According to Ismail and Mohd Ariffin [5], flowers and other fragrant plants can create a relaxing mood, besides beautifying the area. This proves that the traditions of the Malay culture are closely linked to the environment, so much so that the elements of nature appear in and are used harmoniously in Malay art.

2.3. Malay Poetry

According to Howard Nemerov [31], poetry is a form of literature that uses the aesthetic and rhythmic qualities of a language, such as phonesthetics, sound symbolism, and metrics, to evoke meaning in addition to, or in place of, prosaic ostensible meaning. Malay poetry is also commonly used as a structural support for musical forms, such as bangsawan (equivalent to opera or theater), lagu asli (native songs), and dikir barat (equivalent to choir and choral folk song), to emphasize the aesthetic and rhythmic qualities of the Malay language [32]. Perera and Audrey [32] have expressed that the skills involved in Malay poetry include reciting it in a manner suggestive of singing and conjuring up the ability to engage in quick, witty, and subtle dialogue, usually in relation to questions and issues in the daily routines of Malay individuals (pertaining to the surrounding environment and traditions, customs, and beliefs). From the Malay perspective, Malay poetry is a collection of traditional Malay views on aesthetics and surrounding natural beauty, serving as a means for shaping the Malay identity [33]. Malay poetry is said to be one of the most important and well-known sources of Malay aesthetics throughout the Malay Archipelago [34]. Malay poetry includes poems, pantun, gurindam, seloka, folk songs, and syair. According to Haji Musa et al. [35], Malay poetry is an expression of art in its style and design: it serves to communicate the elements of teaching and metaphors to younger generations in a subtle, orderly, and polite way.

Malay poetry has broad meaning, even with the use of very simple words, covering aspects related to the structure of life, origins, scenes, and background of an object [9]. Each phrase in Malay poetry has a definite and implied meaning based on Malay culture and tradition [34]. According to Chan and Cheong Jan [36], the Malay poetry called pantun usually consists of two parts: diversionary (foreshadowing) lines and lines with intended meaning. The diversionary part often contains metaphorical wording for background images, feelings, or emotions in various forms, which are spoken and suggestive. The second part of the pantun is the sequel to the diversionary meanings that the seniman (artist) wishes to convey. In some instances, the diversionary lines have no direct connection to the intended meaning. Such a connection can be seen in a Malay poem entitled Mak Inang:

Bulan terang mengail gelama,Fishing for a croaker under the bright moon,Dapat ikan tenggiri batang,A Spanish mackerel is caught in store,Tengku laksana bulan purnama,Your Highness is much like the full moon,Parasnya manis tak jemu dipandang.Sweetly charming to be gazed evermore.[37]

Poetry description: The first two lines of the pantun are intended to prepare the idea produced over the next two lines. The diversionary (foreshadowing) lines are generally created in styles that portray indirect meaning and analogies. The first two lines offer a situation without a complete metaphor. The above example implies that it was normal for the Malays to go fishing at sea under the moonlight, as they believed that such conditions might result in a massive catch. Hence, the first two lines from the seniman are meant to introduce the final two lines, which display a Malay trait. In the example above, this trait represents a man’s adoration of a woman’s beauty through a metaphor expressed in the form of the bulan purnama (full moon).

Additionally, the art in Malay poetry also reflects the life experiences of the traditional Malay community in previous times. Perera and Audrey [32] noted that Malay poetry constitutes a great collection of traditional Malay views of life and the world around them and is based on the Malays’ pengalaman (experiences). The term peng-alam-an is a combination of a Malay lexeme (prefix–root–suffix), which connotes the human experience, the environment, and the behavior of a person or community and reflects the Malays’ wisdom, perceptions, behavior, and philosophy of life [35]. As cited by Aripin Said [38], peng-alam-an is a complex system that contains natural life, art, customs, traditions, culture, beliefs, and landscape architectural dimensions that are required by individuals to be part of Malay society. An example of the notion of peng-alam-an in Malay poetry can be observed in the song Kurik Kundi:

Nak berkhabar tingginya budi kita ya tuan,Wishing to show others our manners, sir,Nak berkisah kaya tutur bicara,Wishing to speak with graceful words,Kalau tinggi untung jadi bintang,If such is noble, the star is as high,Kalau rendah masih jadi intan.If such is humble, the diamond is as nigh.Teratak mahligai bak dipayung teduhnya,The palace is serene under the shade,Bila budi melingkar anak asuhan,When morality embeds the nurture of children,Adat yang lama berbudi berbahasa,Old traditions in courteous etiquette,Akar kehidupannya.Bear the roots of life.Yang kurik itu kundi,The spotted is the weight,Yang merah saga,The red is the sandal bead,Baik budi indahlah Bahasa,Good manners lead to elegant speech,Pantun lama tinggi kiasannya.Old poems carry deep metaphors.[39]

Kurik Kundi has a broad meaning but uses very simple words. It covers aspects related to the structure of life, origins, and background of an object and scene [13]. It reflects the natural life, art, customs, traditions, culture, beliefs, and landscape architectural dimensions of the Malays, expressing the spiritual truth of Malays, the beauty of Malay arts and designs, and the aesthetic imagery of the Malay community [7]. Kurik Kundi has strong implications for the Malay way of life in determining its suitability based on the continuation of peng-alam-an [24]. For example, the phrase “yang kurik itu kundi” refers to an old spotted seed used as a weight unit in olden times, while the phrase “yang merah itu saga” refers to a newer weight unit in the form of a bright red sandal bead, which depicts the younger generation’s Malay spirit. The words bintang and intan refer to precious elements in the Malays’ cosmological beliefs. Bintang refers to a star, suggesting a belief in the existence of a prominent figure among the Malays. It also appears as the fruit of spirits, as mentioned in an Old Malay manuscript entitled Bustan Al-Salatin (“The Garden of the Sultan”) [20]. Meanwhile, intan (diamond) was believed to be a protective gem associated with the courage to overcome fears in everyday life [20]. Noorizan [40] has explained that teratak mahligai refers to a palace, which implies the house where the Malays reside. In the past, a palace was seen by the Malays as a structure of utmost elegance, so this symbolizes their feelings for their own houses [40]. To the Malays, the house and its landscape reflect a sense of pride and understanding of how to live in harmony with nature. The phrase “bak dipayung teduhnya” signifies a shaded area, which could be a pangkin (veranda), a wakaf (gazebo), or tree shades: being protected from the harsh sun provides comfort for various outdoor activities. The pangkin, wakaf, or tree shades, in Malay home gardens are basically a space for conducting social activities (Figure 3). The pangkin is used by residents to have conversations with neighbors. Plants, especially leafy trees, also provide shade during hot sunny days. The sight, scent, and sensation from flowers, foliage, and fruits, as well as from wind and rain, can immeasurably add to the quality of daily life [15].

Figure 3.

At certain social events, such as wedding ceremonies, the tree shades in a Malay home garden will be used as an extension of the house (source: Wan [41]).

Malay poetry can also depict background settings of the Malay community in certain areas throughout Malaysia. Some examples are as follows:

In the context of the Malay landscape, the use of metaphors in poetry is essential in demonstrating design references. In the past, when the Malays lived in a kampong setting, poetry was used to lace subtleties into conversation, either for important events, social celebrations, or just for entertainment. Metaphors were used to portray background imagery, feelings, and emotions. They told us our history, described where we lived, showed us what our values were, and ultimately reflected who we were [50]. As noted in End [51], Malay poetry depicts the sophistication, subtlety, and intellectual depth of the Malays in using properties from natural phenomena as backdrops to convey intended meaning. This symbolizes the nation’s historical identity and is a depiction of the Malay society’s superior culture in the past.

3. Discussion

Malay literature is a product of Malay society and is based on extended experience with nature and the environment, allowing for ideas in designing the architecture of the Malay landscape. Malay literature is a form of cosmology that involves the integration of thoughts, beliefs, and nature. Every Malay encounter with the environment reflects interdependence. The Malay cultural landscape and Malay literature connect us to the origins of Malay society. Currently, the Malay cultural landscape is under intense pressure from urbanization and the changing social patterns of the Malay community itself, which has led to the risk that it disappears completely. The lack of written materials in this field might cause the Malay cultural landscape to become less popular and less understood by Malay environmental designers. In this review, elements related to the history, environment, and beliefs of the Malay community were taken from Malay literary texts to understand how they are linked to the Malay cultural landscape. Information from such sources can provide a brief overview of the system, customs, regulations, backdrop, and use of natural elements in literature and architecture. Borrowing natural elements for inner reflection is a common theme in the Malay world. Malay literature and Malay culture partially symbolize the Malay faith in the Creator, where art indicates the Malay world is an ecological system that encompasses a link between God, humans, and nature. The Malay cultural landscape also emphasizes the function of the environment in life, reflecting the changing nature of human thinking, suitable methods of obtaining resources, and the instability of nature itself. Human behavior and practices depend on the changes and habits of nature. The formation of Malay customs has been shaped by the Malays’ perceptions of their relationship with nature, since every cultural practice has its own system, method, and rules to achieve this well-balanced interdependence.

4. Conclusions

Malay literature represents a large part of the Malays’ collective living memory and provides a guideline for the modern generation of Malays. This literature is a storehouse for ideas on how Malays have used the land as a vital source for culture and spiritual creation. Hence, intensive preservation efforts should be made to achieve more positive outcomes for the Malay cultural landscape. The Malay cultural landscape can be maintained and should be understood by outsiders as knowledge of cultural privileges that can be identified, experienced, and acknowledged. At the same time, the significance of the Malay culture, traditions, and customs will allow its younger generations to understand their roots and heritage. In conclusion, the three components of sustainability, namely the environment, society, and the economy, are frequently found in Malay culture through literature. The Malay cultural landscape emphasizes the relationship between God, humans, and nature, which influences the Malay lifestyle in achieving sustainability. In this paper, we have discussed the traditional values and meaning of the Malay cultural landscape. Stakeholders are encouraged to use their resources efficiently, to minimize negative impacts on the environment, to offer flexible designs that can accommodate changing needs, and to consider using Malay literary texts as references for future development. A sustainable cultural landscape approach could also help ensure a good social mix for the community. The rich components of the Malay cultural landscape offer a variety of activities that can attract a diverse group of people, while designs that are inspired by Malay literature can lead to a more vibrant environment and a safer landscape.

Author Contributions

M.A.H. initiated the idea and the scope and designed and ran the reviews. M.A.H. performed the document review and wrote the manuscript. M.Y.M.Y., N.A.I., S.I., and N.F.M.A. also were involved in manuscript editing, and they validated the data and proofread the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding and the APC was funded by Universiti Putra Malaysia.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Universiti Putra Malaysia for the financial support given.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mahmud, Z. The Period and Nature of ‘Traditional Settlement in the Malay Penisula’. J. Malay. Branch R. Asiat. Soc. 1970, 43, 81–113. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M.A.; Yunos, M.Y.M.; Utaberta, N.; Ismail, N.A.; Mohd Ariffin, N.F.; Ismail, S. Assessment the Function of Trees as a Landscape Elements: Case Study at Melaka Waterfront. Build. Sci. Constr. J. Teknol. 2015, 75, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Liao, Z.; Wu, Y.; Degefu, D.M.; Zhang, Y. Cultural Sustainability and Vitality of Chinese Vernacular Architecture: A Pedigree for the Spatial Art of Traditional Villages in Jiangnan Region. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.S.; Bakar, J.A.; Ibrahim, F.K. Investigation on the Elements of Malay Landscape Design. Ph.D. Thesis, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Skudai, Malaysia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, N.A.; Mohd Ariffin, N.F. Longing for Culture and Nature: The Malay Rural Cultural Landscape “Desa Tercinta”. J. Teknol. 2015, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, Y.; Moore, N. Heritage, Memory and the Politics of Identity: New Perspectives on the Cultural Landscape; Ashgate Publisher: Abindon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Adat Resam Melayu. 1 October 2017. Available online: http://members.tripod.com/kidd_cruz/adat_resam.htm (accessed on 15 November 2019).

- Al-Ahmadi, A.R. Petua Membina Rumah Melayu: Dari Sudut Etnis Antropologi, edisi ke-2; PNM: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Akmal. Kebudayaan Melayu Riau; pantun, syair, gurindam. J. Risal. 2015, 4, 159–165. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, S. Expanding the historical narrative of early visual modernity in Malaya. Wacana Seni J. Arts Discourse 2018, 17, 41–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.R.; Hasan, A.; Roshdi, S.M. Alam Sebagai Sumber Reka bentuk Motif-Motif Seni Hiasan Fabrik Masyarakat Melayu. In Proceedings of the ISME Colloquium, Melaka, Malaysia, 27–28 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M.A.; Md Yunos, M.Y.; Ismail, N.A.; Ismail, S. Landscape element assessment of melaka historic watrefront through the review on the impression of place. Master’s Thesis, University Putra Malaysia, Seri Kembangan, Malaysia, 2016. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Alimin, A.A. Analisis Wacana Lirik Lagu Bujang Nadi, Lagu Daerah Melayu Sambas, Kalimantan Barat. J. Pendidik. Bhs. 2014, 3, 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Haji Salleh, M. Hang Tuah dalam Budaya Alam Melayu; Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nor Atiah, I.; Noor Fazamimah, A.; Sumarni, I.; Mohd Yazid, M.Y. Understanding Characteristics of the Malay Cultural landscape through Pantun, Woodcarving and Old Literature. Adv. Environ. Biol. 2015, 9, 137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Kafka, F. An Old Manuscript; Schocken: Berlin, Germany, 1917. [Google Scholar]

- Harun, R. Hikayat Tajul Muluk; Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2008; Volume 2, Proyek Penerbitan Buku Sastra Indonesia dan Daerah. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C.C.; Roolvink, R. Sejarah Melayu “Malay Annals”; Oxford University Press: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R. The Pasai Chronicle; Institut Terjemahan & Buku Malaysia: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir, A.H. Rumah Tradisional Melayu Semenanjung Malaysia; Darul Fikir: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hussin, H.; Abu Mansor, R.S.; Omar, R.; Ismail, H.; Hasan, A. Seni Hias Seni Rekareka Bentuk dan Estetika Daripada Persepsi Umum dan Orang Melayu. J. Pengaj. Melayu 2009, 20, 82–98. [Google Scholar]

- Maliki, N.Z. Kampung/Landscape: Rural-Urban Migrants’ Interpretations of Their Home Landscape. The Case of Alor Star and Kuala Lumpur. Ph.D. Thesis, Lincoln University, Lincoln, New Zealand, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wan Muhammad, Wan Ramli, Dollah and Hanapi. Pantang Larang Orang Melayu Tradisional. 27 October 2016. Available online: http://melayu.library.uitm.edu.my/1999/ (accessed on 20 April 2019).

- Aziz, N.F.; Arifin, K.; Ujang, A. Pengaruh Adat Resam, Kepercayaan dan Kebudayaan Terhadap Pembinaan Rumah Melayu Traditional. J. Antarabangsa Alam Tamadun Melayu 2008, 2, 105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Dictionary, V.C. “Folktale”. 10 November 2019. Available online: https://www.vocabulary.com/dictionary/folktale (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- Haji Salleh, M.; Robson, R. The Epic of Hang Tuah; Malay Great Work Series; Silverfish Books: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, K. Hikayat Hang Tuah; Yayasan Karyawan dan Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Zakri, P.A. Laman Impiana; Kumpulan Media Karangkraf: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shamsuddin, S. Townscape Revisited; UTM Press: Skudai, Malaysia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M.A.; Yunos, M.M.; Nangkula, U.; Ismail, N.A.; Arifin, M.N.; Ismail, S. Investigation the types and functions of water features at culture and heritage waterfront: Case of Melaka waterfront. Int. J. Curr. Res. 2015, 7, 2081–2087. [Google Scholar]

- Nemerov, H. Encyclopædia Britannica; Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.: Chicago, CA, USA, 2011; Available online: https://www.britannica.com/art/poetry (accessed on 7 November 2019).

- Perera and Audrey. Musical Practice of Malay ‘Traditional’ Genres. January 2018. Available online: https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/music/Media/PDFs/Article/218d7b98-9c8c-4ca3-b95b-74b8528e38ab.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2019).

- Firduansyah, D.; Rohidi, T.R.; Utomo, U. Guritan: Makna Syair dan Proses Perubahan Fungsi Pada Masyarakat Melayu di Besemah Kota Pagaralam. Cathar. J. Art Educ. 2016, 5, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Perera and Audrey. Yusnor Ef: Songs about Life. August 2010. Available online: https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/music/Media/PDFs/Article/33ad4276-80f9-44f4-828e-d0cc780ec065.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2019).

- Haji Musa, H.; Sheik Said, N.; Che Rodi, R.; Ab Karim, S.S. Hati Budi Melayu: Kajian Keperibadian Sosial Melayu ke Arah Penjanaan melayu Gemilang. J. Lang. Stud. 2012, 12, 163–182. [Google Scholar]

- Cheongjan, C. Malay Traditional Folk Songs in Ulu Tembeling: Its Potential for a Comprehensive Study. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2013, 24, 101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Perak, S.T. Artist, Mak Inang; Cathay Keris: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Said, A. Portrayal of Malay Culture in Malaysian Traditional Songs; Ministry of Culture, Arts and Tourism: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Nurhaliza, S.; Ngah, P.; Asyiqin, N. Kurik Kundi; Suria Records: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Noorizan, M. Menghayati Landskap. In Pengenalan kepada Asas Senibina Landskap; Penerbit Universiti Putra Malaysia: Seri Kembangan, Malaysia, 2008; pp. 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Wan. 8 Taktik Halus Mak Untuk Pujuk Anak Selalu Balik Kampung; Oh Bulan: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hamzah, O. Artist, Tanjung Puteri; Radio Television Malaysia: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Nor, K. Artist, Sri Mersing; RTM Malaysia: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Ramlee, P. Artist, Suria; Merdeka Film Productions: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Salim, S. Artist, Joget Senyum Memikat; RTM Malaysia: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Madun, R. Artist, Menghilir Sungai Pahang; Roslan Madun: Pahang, Malaysia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Yem, M. Artist, Jalak Lenteng; Cathay-Keris Film Productions: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Salim, S. Artist, Pantun Budi; RTM Malaysia: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nurhaliza, S. Artist, Ya Maulai; SRC Record: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- House, C.Y. Cultural Understanding through Folklore; Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute: New Haven, CT, USA, 2005; Available online: http://teachersinstitute.yale.edu/curriculum/units/1993/2/93.02.05.x.html (accessed on 9 December 2019).

- End, G.T.T. Portrayal of Malay Culture in Malaysia Traditional Songs. 2011. Available online: https://gtte.wordpress.com/2011/06/16/portrayal-of-malay-culture-in-malaysian-traditional-songs/ (accessed on 9 December 2019).

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).