Perceived Knowledge, Coping Efficacy and Consumer Consumption Changes in Response to Food Recall

Abstract

:1. Introduction

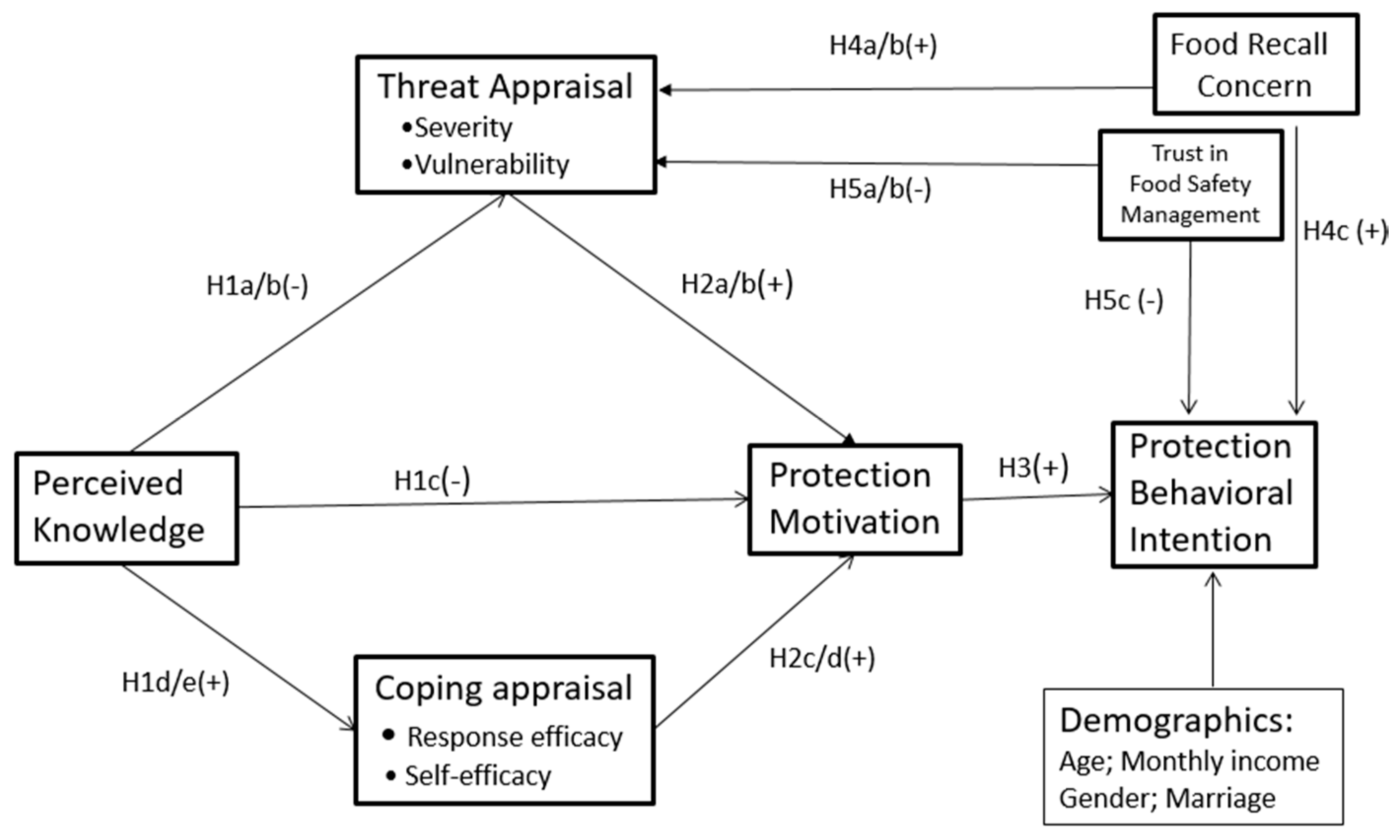

2. Theory and Hypotheses Development

2.1. The Protection Motivation Theory

2.2. Research Model Development

2.2.1. Perceived Knowledge

2.2.2. Threat Appraisal, Coping Appraisal and Protection Motivation

2.2.3. Protection Motivation and Behavioral Intention

2.2.4. Food Recall Concern

2.2.5. Trust in Food Safety Management

3. Methodology

3.1. Measures and Scaling

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Testing

4.2. Structural Model Testing

5. Discussion

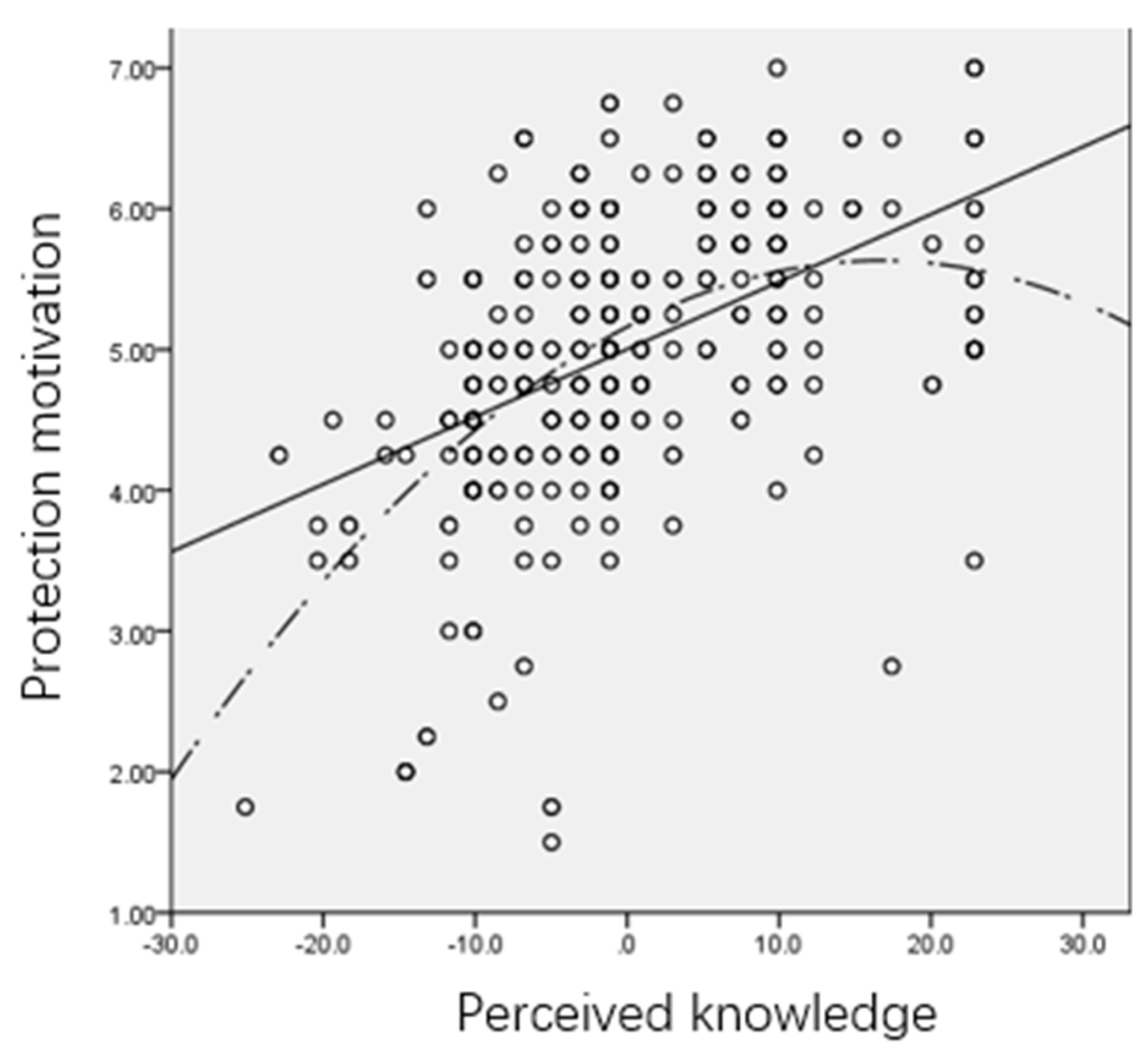

6. Robustness Check

7. Implications and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Flynn, B.B. The financial impact of product recall announcements in China. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 142, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.Z.; Alam, M.J.S. What Determines the Purchase Intention of Liquid Milk during a Food Security Crisis? The Role of Perceived Trust, Knowledge, and Risk. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pozo, V.F.; Schroeder, T.C. Evaluating the costs of meat and poultry recalls to food firms using stock returns. Food Policy 2016, 59, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, M.E.; Griffin, P.M.; Voetsch, A.C.; Mead, P.S. Effectiveness of recall notification: Community response to a nationwide recall of hot dogs and deli meats. J. Food Saf. 2007, 70, 2373–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steelfisher, G.; Weldon, K.; Benson, J.M.; Blendon, R. Public perceptions of food recalls and production safety: Two surveys of the American public. J. Food Saf. 2010, 30, 848–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, R.J.; Dunwoody, S.; Neuwirth, K. Proposed model of the relationship of risk information seeking and processing to the development of preventive behaviors. Environ. Res. 1999, 80, S230–S245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, I.U.; Ji, S.; Yeo, C. Values and Green Product Purchase Behavior: The Moderating Effects of the Role of Government and Media Exposure. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fleming, K.; Thorson, E.; Zhang, Y. Going beyond exposure to local news media: An information-processing examination of public perceptions of food safety. J. Health Commun. 2006, 11, 789–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcock, A.; Pun, M.; Khanona, J.; Aung, M. Technology, Consumer attitudes, knowledge and behaviour: A review of food safety issues. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2004, 15, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.W. Cognitive and psychological processes in fear appeals and attitude change: A revised theory of protection motivation. In Social Psychophysiology: A Sourcebook; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 153–176. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, R.W. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change1. J. Psychol. 1975, 91, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-F. Extending the protection motivation theory model to predict public safe food choice behavioural intentions in Taiwan. Food Control 2016, 68, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, E.; Röös, E. Fear of climate change consequences and predictors of intentions to alter meat consumption. Food Policy 2016, 62, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K.A. A practitioner’s guide to persuasion: An overview of 15 selected persuasion theories, models and frameworks. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 74, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A.; Freeman, W.; Lightsey, R. Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Milne, S.; Sheeran, P.; Orbell, S. Prediction and intervention in health-related behavior: A meta-analytic review of protection motivation theory. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 30, 106–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, H.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980; pp. 178–182. [Google Scholar]

- Peake, W.O.; Detre, J.D.; Carlson, C.C. One bad apple spoils the bunch? An exploration of broad consumption changes in response to food recalls. Food Policy 2014, 49, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. The effects of different types of trust on consumer perceptions of food safety: An empirical study of consumers in Beijing Municipality, China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2013, 5, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallman, W.K.; Cuite, C.L.; Hooker, N.H. Consumer Responses to Food Recalls: 2008 National Survey Report. 2009. Available online: https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers−lib/48426/PDF/1/ (accessed on 19 October 2018).

- Pomarici, E.; Vecchio, R. Millennial generation attitudes to sustainable wine: An exploratory study on Italian consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, B.; Kwon, S.; Yang, B.-H.; Paik, K.-C.; Kim, S.H.; Roh, S.; Song, J.; Schwarzer, R. Social-cognitive predictors of dietary behaviors in South Korean men and women. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 15, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zaalberg, R.; Midden, C.; Meijnders, A.; McCalley, T. Prevention, adaptation, and threat denial: Flooding experiences in the Netherlands. Risk Anal. Int. J. 2009, 29, 1759–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppright, D.R.; Tanner, J.F., Jr.; Hunt, J.B. Knowledge and the ordered protection motivation model: Tools for preventing AIDS. J. Bus. Res. 1994, 30, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; Mothersbaugh, D.L.; Feick, L. Consumer knowledge assessment. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brucks, M.J. The effects of product class knowledge on information search behavior. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellens, W.; Zaalberg, R.; De Maeyer, P. The informed society: An analysis of the public’s information-seeking behavior regarding coastal flood risks. Risk Anal. Int. J. 2012, 32, 1369–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hudson, G.M.; Watson, P.J.; Fairall, L.; Jamieson, A.G.; Schwabe, J.W.J. Insights into the recruitment of class IIa histone deacetylases (HDACs) to the SMRT/NCoR transcriptional repression complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 18237–18244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Falk, M. Organizational change, new information and communication technologies and the demand for labor in services. In The New Economy and Economic Growth in Europe and the US; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 161–192. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, Personality, and Behavior; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Scarpa, R.; Thiene, M. Organic food choices and Protection Motivation Theory: Addressing the psychological sources of heterogeneity. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, D.L.; Prentice-Dunn, S.; Rogers, R.W.J. A meta-analysis of research on protection motivation theory. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 30, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, T.L.; Schroeder, T.C.; Mintert, J. Impacts of meat product recalls on consumer demand in the USA. Appl. Econ. 2004, 36, 897–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasuwa, G. The Role of Individual- and Contextual-Level Social Capital in Product Boycotting: A Multilevel Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Earle, T.C. Trust in risk management: A model-based review of empirical research. Risk Anal. An Int. J. 2010, 30, 541–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talton, R.Y. Winning Consumer Trust and Loyalty in Distrust-dominated Environments: A Consumer Perspective; Case Western Reserve University: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Grayson, K.; Johnson, D.; Chen, D.-F.R. Is firm trust essential in a trusted environment? How trust in the business context influences customers. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 45, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjærnes, U.; Harvey, M.; Warde, A. Trust in Food: A Comparative and Institutional Analysis; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 142–163. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Wu, H.; Yin, S.; Chen, X. Introductiong to 2017 China Developmet Report on Food Safety; Pecking University Press: Beijing, China, 2017; pp. 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- De Steur, H.; Mogendi, J.B.; Wesana, J.; Makokha, A.; Gellynck, X. Stakeholder reactions toward iodine biofortified foods. An application of protection motivation theory. Appetite 2015, 92, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, S.-M.; Seo, S.H.; Lee, Y.; Moon, G.-I.; Kim, M.-S.; Park, J.-H. Consumers’ knowledge and safety perceptions of food additives: Evaluation on the effectiveness of transmitting information on preservatives. Food Control 2011, 22, 1054–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Bookstein, F.L. Two structural equation models: LISREL and PLS applied to consumer exit-voice theory. J. Mark. Res. 1982, 19, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chiu, C.-M.; Wang, E.T. Understanding Web-based learning continuance intention: The role of subjective task value. Inf. Manag. 2008, 45, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: London, UK, 2016; pp. 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W.; Yao, N.C.; Ma, B.; Wang, F. Consumers’ risk perception, information seeking, and intention to purchase genetically modified food. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 2182–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picón-Berjoyo, A.; Ruiz-Moreno, C.; Castro, I. A mediating and multigroup analysis of customer loyalty. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 3, 701–713. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, C.C.; Peake, W.O. Rethinking food recall communications for consumers. Iridescent 2012, 2, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, W.; Abler, D.; Zhu, L.; Li, T.; Lin, G. Consumer Preferences and Welfare Evaluation under Current Food Inspection Measures in China: Evidence from Real Experiment Choice of Rice Labels. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Construct | Item | Measurement | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Severity | PS1 | I think that the recalled food could cause some type of health problems. | [12] |

| PS2 | The thought of getting a foodborne illness scares me. | ||

| PS3 | Consumption of the recalled food could cause me to be ill for a long time. | ||

| PS4 | Foods produced by the recalling firms should be shut down permanently. | ||

| Perceived Vulnerability | PV1 | I believe that the likelihood of being affected by recalled food is relatively high in China. | [12] |

| PV2 | Eating a recalled food is not a concern to me. | ||

| PV3 | I view food recall arising from abuse of additives in the media to be a contained threat and not really a threat to me (reverse coding). | ||

| PV4 | I am healthy and do not believe that I am susceptible to a foodborne illness associated with restaurants. | ||

| Perceived Response Efficacy | PRE1 | Eating natural foods can reduce health risks caused by food additive safety scandals. | [12,20] |

| PRE2 | Stopping eating the recalled food can reduce health risks caused by food additive safety scandals. | ||

| PRE3 | Stopping buying the recalled food can reduce health risks caused by food additive safety scandals. | ||

| PRE4 | I trust more in non-additive foods than in the recalled. | ||

| Perceived Self-efficacy | If my usual food choice is subject to a major food recall issue: | ||

| PSE1 | I know the bad effects of the additives involved in the recalled product. | [12,40] | |

| PSE2 | I can easily choose an alternative safer product. | ||

| PSE3 | I have time to find an alternative safer product. | ||

| PSE4 | I can afford an expensive alternative safer product (e.g. import commodity). | ||

| Protection Motivation | PM1 | I would boycott a firm involved in the food safety scandals. | [10,12] |

| PM2 | I would boycott the firm involved in a food recall issue. | ||

| PM3 | I would boycott the products with the same brand of the recalled food. | ||

| PM4 | I would boycott the products produced by the recalling manufacturer. | ||

| Protection Behavioral Intention | PBI1 | I would stop consuming the recalled food with the specific brand until I felt it was safe. | [33] |

| PBI2 | I would stop consuming all the food in the same line as the recalled food until I felt it was safe. | ||

| PBI3 | I would stop consuming all the food with the same additive which caused food recall until I felt it was safe. | ||

| PBI4 | I intend to consume food with natural additives. | ||

| Perceived Knowledge | PK1 | Preservatives are used for processed foods in order to minimize quality changes. | [41] |

| PK2 | Preservatives are used for processed foods in order to extend shelf life. | ||

| PK3 | Preservatives are used for processed foods in order to inhibit microbial growth. | ||

| PK4 | It is safe to consume processed foods containing preservatives. | ||

| PK5 | Intake of processed foods containing preservatives is safe if they are consumed within acceptable daily intake. | ||

| Food Recall Concern | FRC1 | I am typically concerned by reports of food recalls. | [18] |

| FRC2 | A food recall has never affected me (reverse coded). | ||

| FRC3 | I feel that my health safety is threatened by food recall situations. | ||

| FRC4 | When I read and/or hear about a food recall, I tend to seek out additional information related to that recall. | ||

| Trust in Food Safety Management | How much trust do you have in the following institutions or persons that they are conscious of their responsibilities in food safety affairs? | [12,19] | |

| TFSM1 | The State Food and Drug Administration and the sub-bureaus. | ||

| TFSM2 | Food safety experts and scholars. | ||

| TFSM3 | Food manufacturers and retailers. | ||

| TFSM4 | Food certification bodies. |

| Construct | Item | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Recall Concern (FRC) | FRC1 | 0.79 | 0.85 | 0.89 | 0.62 |

| FRC2 | 0.83 | ||||

| FRC3 | 0.77 | ||||

| FRC4 | 0.77 | ||||

| Perceived Knowledge (PK) | PK1 | 0.81 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.75 |

| PK2 | 0.89 | ||||

| PK3 | 0.89 | ||||

| PK4 | 0.89 | ||||

| PK5 | 0.86 | ||||

| Protection Behavioral Intention (PBI) | PBI1 | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.67 |

| PBI2 | 0.84 | ||||

| PBI3 | 0.78 | ||||

| PBI4 | 0.80 | ||||

| Protection Motivation (PM) | PM1 | 0.72 | 0.78 | 0.86 | 0.61 |

| PM2 | 0.83 | ||||

| PM3 | 0.78 | ||||

| PM4 | 0.78 | ||||

| Perceived Response Efficacy (PRE) | PRE1 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.78 |

| PRE2 | 0.91 | ||||

| PRE3 | 0.88 | ||||

| PRE4 | 0.87 | ||||

| Perceived Self-Efficacy (PSE) | PSE1 | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.88 | 0.65 |

| PSE2 | 0.79 | ||||

| PSE3 | 0.87 | ||||

| PSE4 | 0.77 | ||||

| Perceived Severity | PS1 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.77 |

| PS2 | 0.90 | ||||

| PS3 | 0.88 | ||||

| PS4 | 0.88 | ||||

| Perceived Vulnerability (PV) | PV1 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.77 |

| PV2 | 0.90 | ||||

| PV3 | 0.84 | ||||

| PV4 | 0.86 | ||||

| Trust in Food Safety Management (TFSM) | TFSM1 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.68 |

| TFSM2 | 0.89 | ||||

| TFSM3 | 0.78 | ||||

| TFSM4 | 0.84 | ||||

| TFSM5 | 0.71 |

| Construct | Mean | SD | FRC | KNOW | PBI | PM | PRE | PSE | PS | PV | TFSM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Recall Concern (FRC) | 5.46 | 0.79 | 0.79 | ||||||||

| Perceived Knowledge (PK) | 5.02 | 0.97 | 0.37 | 0.87 | |||||||

| Protection Behavioral Intention (PBI) | 5.16 | 0.83 | 0.58** | 0.44** | 0.82 | ||||||

| Protection Motivation (PM) | 5 | 0.96 | 0.42** | 0.51** | 0.53** | 0.78 | |||||

| Perceived Response Efficacy (PRE) | 5.31 | 1.05 | 0.31 | 0.58** | 0.43** | 0.45** | 0.88 | ||||

| Perceived Self−Efficacy (PSE) | 4.75 | 0.88 | 0.43** | 0.47** | 0.50** | 0.46** | 0.35 | 0.81 | |||

| Perceived Severity (PS) | 5.19 | 0.93 | 0.53** | 0.41** | 0.69** | 0.53** | 0.40** | 0.52** | 0.88 | ||

| Perceived Vulnerability (PV) | 4.78 | 1.21 | 0.43 | 0.4 | 0.35 | 0.47 | 0.3 | 0.47 | 0.51** | 0.83 | |

| Trust in Food Safety Management (TFSM) | 3.68 | 1.12 | −0.26 | −0.43** | −0.38** | −0.34 | −0.27 | −0.36** | −0.41** | −0.33 | 0.83 |

| Hypothesis | Path Coefficient | Standard Deviation | T Statistics Values | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a: Perceived knowledge −> Perceived severity | 0.39*** | 0.045 | 8.73 | NS |

| H1b: Perceived knowledge−> Perceived vulnerability | 0.18** | 0.057 | 3.17 | NS |

| H1c: Perceived knowledge−> Protection motivation | 0.25*** | 0.049 | 5.08 | NS |

| H1d: Perceived knowledge−> Response efficacy | 0.58*** | 0.034 | 16.89 | Supported |

| H1e: Perceived knowledge −> Self−efficacy | 0.47*** | 0.037 | 12.79 | Supported |

| H2a: Perceived severity −> Protection motivation | −0.017 | 0.037 | 0.461 | NS |

| H2b: Perceived vulnerability −> Protection motivation | 0.31*** | 0.05 | 6.12 | Supported |

| H2c: Response efficacy −> Protection motivation | 0.14** | 0.043 | 3.17 | Supported |

| H2d: Self−efficacy −> Protection motivation | 0.15*** | 0.042 | 3.46 | Supported |

| H3: Protection motivation −> Protection intention | 0.30*** | 0.039 | 7.82 | Supported |

| H4a: Recall concern −>Perceived severity | −0.05 | 0.037682 | 1.32 | NS |

| H4b: Recall concern −>Perceived vulnerability | 0.42*** | 0.04 | 9.83 | Supported |

| H4c: Recall concern −>Protection intention | 0.39*** | 0.0371 | 10.44 | Supported |

| H5a: TFSM −> Perceived severity | −0.24*** | 0.046 | 5.24 | Supported |

| H5b: TFSM −> Perceived vulnerability | −0.14*** | 0.045 | 3.21 | Supported |

| H5c: TFSM −> Protection intention | −0.31*** | 0.05 | 6.12 | Supported |

| Age −>Protection intention | 0.03** | 0.01 | 3.02 | |

| Gender −> Protection intention | 0.11*** | 0.012 | 9.17 | |

| Monthly income−> Protection intention | 0.07 | 0.06 | 1.17 | |

| Marriage −> Protection intention | 0.03** | 0.01 | 3.02 |

| Model | Independent Variable | Std. Coefficients | Std. Error | T−Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Perceived knowledge | 0.48 | 0.05 | 13.53 |

| 2 | Perceived knowledge | 0.42 | 0.31 | 1.957 |

| Square of perceived knowledge | 0.06 | 0.031 | 0.29 |

| Model | Independent Variable | Std. Coefficients | Std. Error | T−Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Perceived knowledge | 0.40 | 0.04 | 11.05 |

| 2 | Perceived knowledge | 0.28 | 0.21 | 1.29 |

| Square of perceived knowledge | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.55 |

| Model | Independent Variable | Std. Coefficients | Std. Error | T−Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Perceived knowledge | 0.45 | 0.03 | 12.49 |

| 2 | Perceived knowledge | 1.52 | 0.21 | 6.55 |

| Square of perceived knowledge | −1.09 | 0.02 | −4.69 |

| Hypotheses and Path | Survey Sound (Round 1 vs. 2) | Marital Status (Married vs. Single) | Gender (Female vs. Male) | Education (High vs. Low) | Age (Young vs. Old) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dif. of Coeff. | p Value | Dif. of Coeff. | p Value | Dif. of Coeff. | p Value | Dif. of Coeff. | p Value | Dif. of Coeff. | p Value | |

| H1a: Perceived knowledge −> Perceived severity | 0.159 | 0.968 | 0.107 | 0.902 | 0.072 | 0.828 | 0.072 | 0.167 | 0.061 | 0.217 |

| H1b: Perceived knowledge−> Perceived vulnerability | 0.095 | 0.211 | 0.07 | 0.262 | 0.121 | 0.873 | 0.116 | 0.875 | 0.114 | 0.842 |

| H1c: Perceived knowledge−> Protection motivation | 0.065 | 0.292 | 0.022 | 0.398 | 0.072 | 0.788 | 0.024 | 0.396 | 0.03 | 0.368 |

| H1d: Perceived knowledge−> Response efficacy | 0.092 | 0.912 | 0.025 | 0.66 | 0.002 | 0.489 | 0.052 | 0.19 | 0.022 | 0.64 |

| H1e: Perceived knowledge −> Self−efficacy | 0.001 | 0.503 | 0.046 | 0.244 | 0.145 | 0.986 | 0.009 | 0.55 | 0.037 | 0.707 |

| H2a: Perceived severity −> Protection motivation | 0.057 | 0.778 | 0.086 | 0.1 | 0.034 | 0.697 | 0.078 | 0.126 | 0.097 | 0.928 |

| H2b: Perceived vulnerability −> Protection motivation | 0.039 | 0.633 | 0.043 | 0.678 | 0.124 | 0.905 | 0.067 | 0.759 | 0.038 | 0.356 |

| H2c: Response efficacy −> Protection motivation | 0.128 | 0.105 | 0.056 | 0.232 | 0.061 | 0.219 | 0.056 | 0.239 | 0.003 | 0.494 |

| H2d: Self−efficacy −> Protection motivation | 0.101 | 0.804 | 0.085 | 0.859 | 0.133 | 0.047 | 0.014 | 0.435 | 0.005 | 0.475 |

| H3: Protection motivation −> Protection intention | 0.099 | 0.109 | 0.089 | 0.873 | 0.028 | 0.655 | 0.049 | 0.763 | 0.063 | 0.811 |

| H4a: Recall concern −>Perceived severity | 0.039 | 0.305 | 0.009 | 0.449 | 0.027 | 0.657 | 0.044 | 0.741 | 0.086 | 0.099 |

| H4b: Recall concern −>Perceived vulnerability | 0.111 | 0.916 | 0.069 | 0.814 | 0.011 | 0.444 | 0.037 | 0.32 | 0.071 | 0.197 |

| H4c: Recall concern −>Protection intention | 0.16 | 0.991 | 0.017 | 0.602 | 0.002 | 0.518 | 0.037 | 0.291 | 0.017 | 0.400 |

| H5a: TFSM −> Perceived severity | 0.069 | 0.769 | 0.104 | 0.886 | 0.05 | 0.73 | 0.097 | 0.89 | 0.137 | 0.059 |

| H5b: TFSM −> Perceived vulnerability | 0.078 | 0.204 | 0.035 | 0.652 | 0.061 | 0.773 | 0.093 | 0.885 | 0.056 | 0.749 |

| H5c: TFSM −> Protection motivation | 0.043 | 0.698 | 0.093 | 0.086 | 0.077 | 0.12 | 0.063 | 0.847 | 0.019 | 0.387 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liao, C.; Yu, H.; Zhu, W. Perceived Knowledge, Coping Efficacy and Consumer Consumption Changes in Response to Food Recall. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072696

Liao C, Yu H, Zhu W. Perceived Knowledge, Coping Efficacy and Consumer Consumption Changes in Response to Food Recall. Sustainability. 2020; 12(7):2696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072696

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiao, Chuanhui, Huang Yu, and Weiwei Zhu. 2020. "Perceived Knowledge, Coping Efficacy and Consumer Consumption Changes in Response to Food Recall" Sustainability 12, no. 7: 2696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072696

APA StyleLiao, C., Yu, H., & Zhu, W. (2020). Perceived Knowledge, Coping Efficacy and Consumer Consumption Changes in Response to Food Recall. Sustainability, 12(7), 2696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072696