Availability and Use of Work–Life Balance Programs: Relationship with Organizational Profitability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Job Demands-Resources Model

2.2. WLBPs, Availability of WLBPs, and Profitability

2.3. WLBPs, Use of WLBPs, and Profitability

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample

3.2. Measures

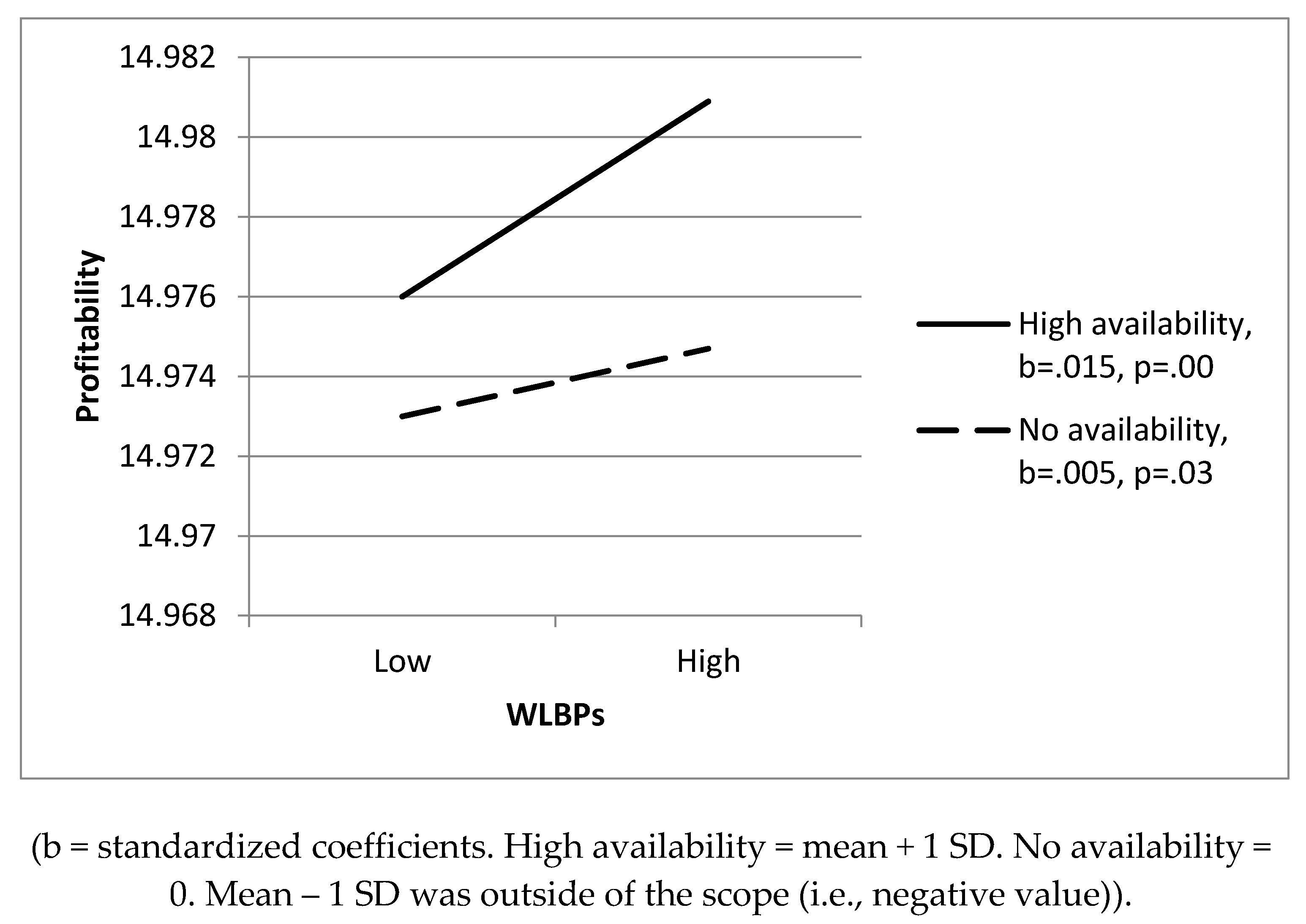

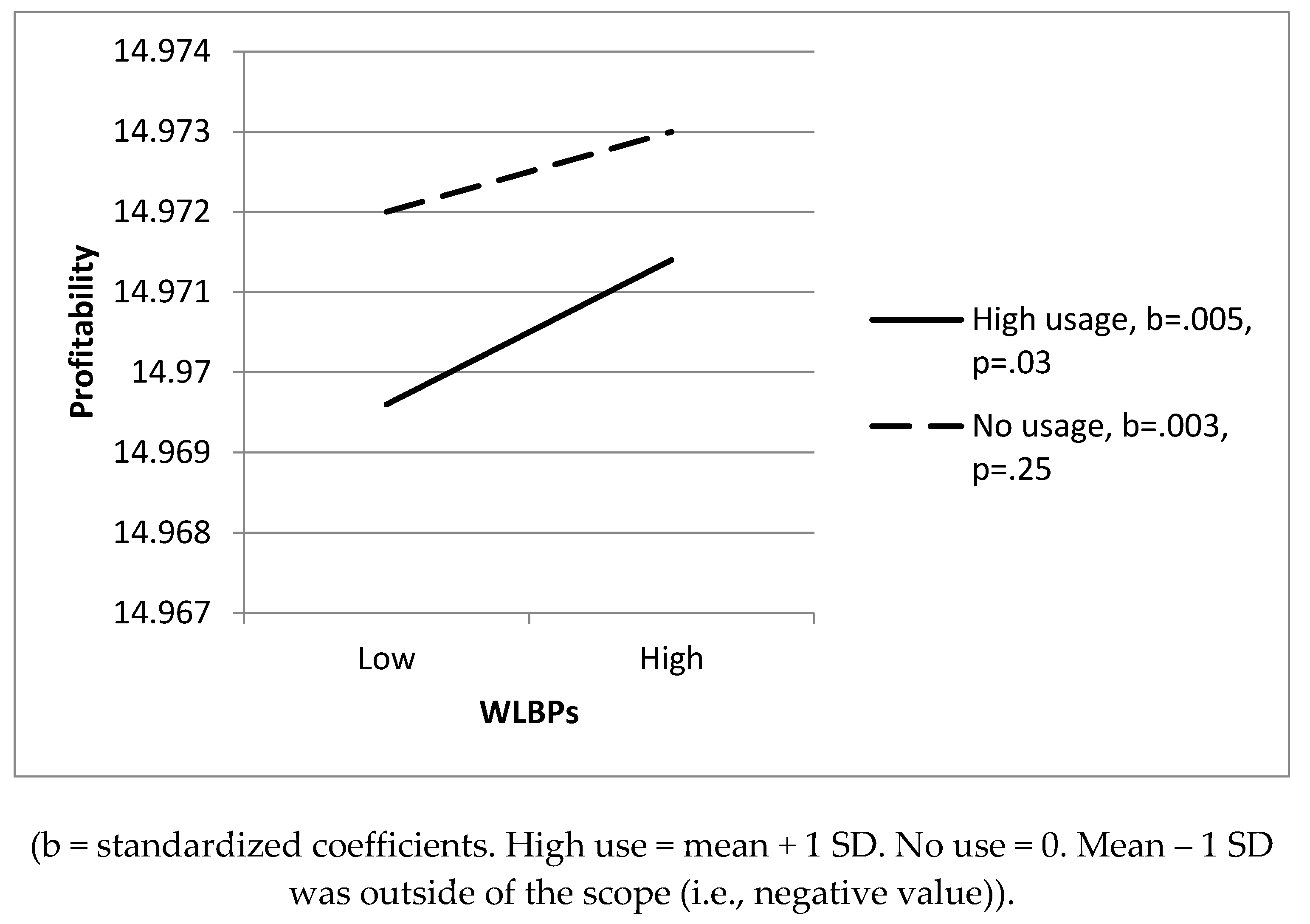

4. Results

5. Discussions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chang, H.P.; Hsieh, C.M.; Lan, M.Y.; Chen, H.S. Examining the moderating effects of work–life balance between human resource practices and intention to stay. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankevičiūtė, Ž.; Savanevičienė, A. Designing sustainable HRM: The core characteristics of emerging field. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauregard, T.A.; Henry, L.C. Making the link between work–life balance practices and organizational performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2009, 19, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.J. Added benefits: The link between work–life benefits and organizational citizenship behavior. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 801–815. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Verma, A. Explaining organizational responsiveness to work-life balance issues: The role of business strategy and high-performance work systems. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 51, 407–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Baltes, B.B.; Matthews, R.A. How work-family research can finally have an impact in organizations. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 4, 352–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sivatte, I.; Gordon, J.R.; Rojo, P.; Olmos, R. The impact of work-life culture on organizational productivity. Pers. Rev. 2015, 44, 883–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, E.L.; Kossek, E.E.; Hammer, L.B.; Durham, M.; Bray, J.; Chermack, K.; Murphy, L.A.; Kaskubar, D. Getting there from here: Research on the effects of work–family initiatives on work–family conflict and business outcomes. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2008, 2, 305–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D.E.; Ostroff, C. Understanding hrm–firm performance linkages: The role of the “strength” of the HRM system. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004, 29, 203–221. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, A.M.; Kossek, E.E. Work-life policy implementation: Breaking down or creating barriers to inclusiveness? Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 47, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B. The job demands-resources model: Challenges for future research. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2011, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Van Veldhoven, M.; Xanthopoulou, D. Beyond the demand-control model. J. Pers. Psychol. 2010, 9, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W. A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health; Bauer, G.F., Hämmig, O., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 43–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kossek, E.E.; Ozeki, C. Work–family conflict, policies, and the job–life satisfaction relationship: A review and directions for organizational behavior–human resources research. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khilji, S.E.; Wang, X. ‘Intended’and ‘implemented’HRM: The missing linchpin in strategic human resource management research. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 17, 1171–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piening, E.P.; Baluch, A.M.; Ridder, H.G. Mind the intended-implemented gap: Understanding employees’ perceptions of HRM. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 53, 545–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veth, K.N.; Van der Heijden, B.I.; Korzilius, H.P.; De Lange, A.H.; Emans, B.J. Bridge over an aging population: Examining longitudinal relations among human resource management, social support, and employee outcomes among bridge workers. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bond, S.; Wise, S. Family leave policies and devolution to the line. Pers. Rev. 2003, 32, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, W.J.; Buffardi, L.C. Work–life benefits and job pursuit intentions: The role of anticipated organizational support. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 65, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.L.; Quick, J.C.; Hitt, M.A.; Moesel, D. Politics, lack of career progress, and work/home conflict: Stress and strain for working women. Sex Roles 1990, 23, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandura, T.A.; Lankau, M.J. Relationships of gender, family responsibility and flexible work hours to organizational commitment and job satisfaction. J. Organ. Behav. 1997, 18, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, S.L.; Crooker, K.J. Who appreciates family-responsive human resource policies: The impact of family-friendly policies on the organizational attachment of parents and non-parents. Pers. Psychol. 1995, 48, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, T.D. Family-supportive work environments: The role of organizational perceptions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2001, 58, 414–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baughman, R.; DiNardi, D.; Holtz-Eakin, D. Productivity and wage effects of “family-friendly” fringe benefits. Int. J. Manpow. 2003, 24, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, M.M. Share price reactions to work-family initiatives: An institutional perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 497–505. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.O.; Rao, J.M. Balancing employment and fatherhood: A systems perspective. J. Fam. Issues 1997, 18, 386–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleck, J.H. Are “family-supportive” employer policies relevant to men? In Men, Work, and Family; Hood, J.C., Ed.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 217–237. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, D.T. Promoting work/family balance: An organization-change approach. Organ. Dyn. 1990, 18, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailyn, L. The impact of corporate culture on work-family integration. In Integrating Work and Family: Challenges and Choices for a Changing World; Parasuraman, S., Greenhaus, J.H., Eds.; Quorum Books: Westport, CT, USA, 1997; pp. 209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Liff, S.; Cameron, I. Changing equality cultures to move beyond ‘women’s problems’. Gend. Work Organ. 1997, 4, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlow, L.A. Putting the work back into work/family. Group Organ. Manag. 1995, 20, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, S.C. If you can use them: Flexibility policies, organizational commitment, and perceived performance. Ind. Relat. 2003, 42, 145–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, K. Father time: Flexible work arrangements and the law firm’s failure of the family. Stanford Law Rev. 2001, 53, 967–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; Russell, J.E. Parental leave of absence: Some not so family-friendly implications. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 29, 166–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judiesch, M.K.; Lyness, K.S. Left behind? The impact of leaves of absence on managers’ career success. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 641–651. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse, G.; Zetlin, D. ‘Family friendly’policies: Distribution and implementation in Australian workplaces. Econ. Labour Relat. Rev. 1999, 10, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenninkmeijer, V.; Demerouti, E.; le Blanc, P.M.; van Emmerik, I.H. Regulatory focus at work. Career Dev. Int. 2010, 15, 708–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Giauque, D.; Anderfuhren-Biget, S.; Varone, F. Stress and turnover intents in international organizations: Social support and work–life balance as resources. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 30, 879–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltes, B.B.; Briggs, T.E.; Huff, J.W.; Wright, J.A.; Neuman, G.A. Flexible and compressed workweek schedules: A meta-analysis of their effects on work-related criteria. J. Appl. Psychol. 1999, 84, 496–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Economic Advisors. Work–Life Balance and the Economics of Workplace Flexibility; 2010. Available online: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/files/documents/100331-cea-economics-workplace-flexibility.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2020).

- Goff, S.J.; Mount, M.K.; Jamison, R.L. Employer supported child care, work/family conflict, and absenteeism: A field study. Pers. Psychol. 1990, 43, 793–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haar, J.M.; Russo, M.; Suñe, A.; Ollier-Malaterre, A. Outcomes of work–life balance on job satisfaction, life satisfaction and mental health: A study across seven cultures. J. Vocat. Behav. 2014, 85, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Konrad, A.M. Causality between high-performance work systems and organizational performance. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 973–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.M.; Gardner, T.M.; Moynihan, L.M.; Allen, M.R. The relationship between HR practices and firm performance: Examining causal order. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 409–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Garmendia, A.; Ali, M.; Konrad, A.M.; Madinabeitia-Olabarria, D. HRM systems and employee affective commitment: The role of employee gender. Gender Manag. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Profitability T3 | 14.97 | 0.09 | ||||||||

| 2. Profitability T1 | 14.97 | 0.09 | 0.96 ** | |||||||

| 3. Manufacturing T1 | 0.28 | 0.45 | 0.03 * | 0.03 | ||||||

| 4. Firm size T1 | 2.01 | 1.18 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.15 ** | |||||

| 5. Differentiation strategy T1 | 0.86 | 0.95 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.13 ** | 0.20 ** | ||||

| 6. Union density T1 | 0.07 | 0.22 | −0.02 | −0.00 | 0.06 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.07 ** | |||

| 7. Work–life balance programs (WLBPs) T1 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.05 ** | 0.04 * | −0.01 | 0.39 ** | 0.10 ** | 0.26 ** | ||

| 8. Use of WLBPs T2 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.13 ** | 0.08 ** | 0.07 ** | 0.25 ** | |

| 9. Availability of WLBPs T2 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.07 ** | 0.05 ** | −0.01 | 0.26 ** | 0.12 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.60 ** |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profitability at T1 | 0.96 ** | 0.96 ** | 0.96 ** | 0.96 ** |

| Manufacturing at T1 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Firm size at T1 | 0.02 ** | 0.01 † | 0.01 † | 0.01 † |

| Differentiation strategy at T1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Union density at T1 | −0.02 ** | −0.02 ** | −0.02 ** | −0.02 ** |

| WLBPs at T1 (1) | 0.01 * | 0.01 * | 0.01 * | |

| Use of WLBPs at T2 (2) | −0.02 ** | −0.02 ** | −0.02 ** | |

| Availability of WLBPs at T2 (3) | 0.02 ** | 0.02 ** | 0.02 ** | |

| (1) X (2) | 0.02 ** | |||

| (1) X (3) | 0.02 † | |||

| R2 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 |

| Δ R2 | 0.001 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.000 † |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shin, D.; Enoh, J. Availability and Use of Work–Life Balance Programs: Relationship with Organizational Profitability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2965. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072965

Shin D, Enoh J. Availability and Use of Work–Life Balance Programs: Relationship with Organizational Profitability. Sustainability. 2020; 12(7):2965. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072965

Chicago/Turabian StyleShin, DuckJung, and Jackson Enoh. 2020. "Availability and Use of Work–Life Balance Programs: Relationship with Organizational Profitability" Sustainability 12, no. 7: 2965. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072965

APA StyleShin, D., & Enoh, J. (2020). Availability and Use of Work–Life Balance Programs: Relationship with Organizational Profitability. Sustainability, 12(7), 2965. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072965