To investigate how the time until completion affects the acquirer post-M&A, we study several quantitative indicators, including stock performance, financial performance, and operational performance. We also investigate how time until deal completion affects the likelihood of failure, and then conduct a survival analysis.

4.1. Stock Performance

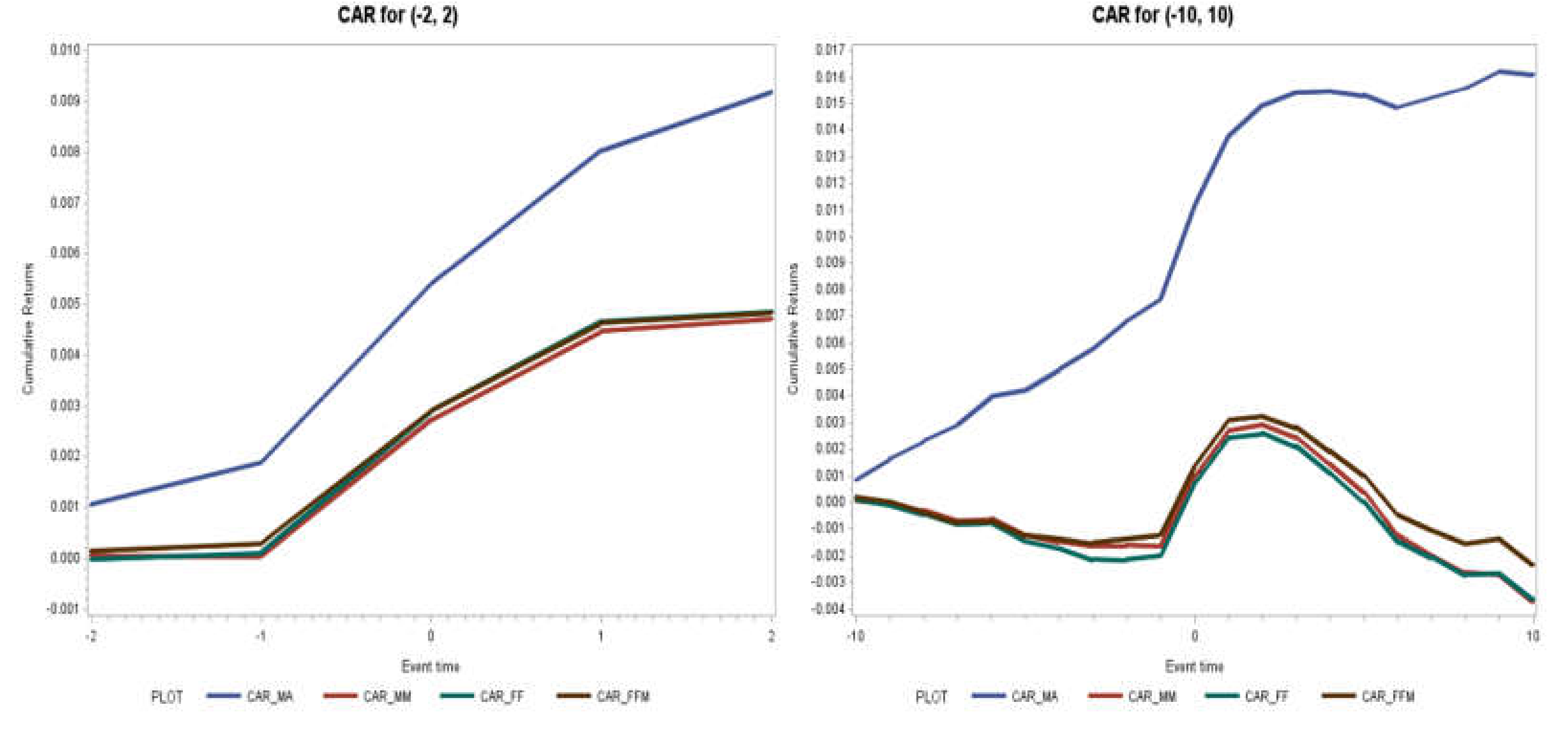

Table 3 presents the results of our tests for the due diligence and overdue hypotheses using stock performance. For the short-term analysis, we use cumulative abnormal return (CAR) to measure the stock performance of the acquirer one month and three months after the deal, as in Equation (8). Due to the misspecification bias related to using CAR to measure long-horizon returns, we adopt the buy-and-hold abnormal returns (BHAR) to measure stock performance six months, one year, two years, and three years after the deal following Kothari and Warner [

40], as in Equation (9). In this study, we focus on the post-merger CAR and BHAR because the acquirer was independent of the target at the announcement date. The deal is effective only after the deal closes or is consummated. To estimate the expected returns, we use the constant mean-adjusted model for all subsequent regressions after confirming that our results do not substantially differ across the different measurement approaches outlined above. We run a panel regression using a squared term of time until completion to test the inverse U-shaped relationship between stock performance and time until deal completion:

where

is the cumulative abnormal returns of the acquirer or newly merged firm,

is the time until deal completion,

is the squared term of time until deal completion,

are firm fixed effects used to control for time-invariant heterogeneity among firms, and

is the error term. The control variables are the national- and firm-level and deal-specific variables, as explained above. All variables are defined in

Appendix A. The Wald tests to verify that the quadratic terms in the models are equal to zero are reported. In addition, the turning point of the quadratic relationship between time until deal completion and the dependent variable is reported, as well as the result and implication of the stringent test of quadratic relation, following Lind and Mehlum [

36]. Standard errors are corrected for heteroscedasticity and clustered by firm and year.

The results are shown in

Table 3 indicate a negative sign on the squared term of time until deal completion, confirming an inverse U-shaped relationship. We subject the model to the stringent test of Lind and Mehlum [

36]. The null hypothesis of monotone or U-shaped relationship is strongly rejected, indicating an inverse U-shaped relationship between time until deal completion and stock performance, and thus, confirming hypotheses 1 and 3. In other words, the results are shown in

Table 3 support both the due diligence hypothesis and the overdue hypothesis. This result implies that, up until a certain optimal period of deal completion, post-M&A stock performance measured by cumulative abnormal returns or buy-and-hold abnormal returns increases until it reaches a maximum; when time until deal completion extends beyond this optimal time, however, stock performance declines, as the possible existence of challenges to the deal is being signaled. The results for various time intervals show that our findings are robust to various time specifications. The Wald test that the quadratic term in the model is zero is strongly rejected in all time intervals except for one year after deal completion, where it is marginally rejected at the 10% level. Interestingly, the extremum revealed empirically in our sample for the one-month interval is 455 days (one year and three months), which is far beyond the mean period of about two months for deal completion in our sample. This indicates that deals that should take an average of about two months, but that extend beyond one year arouse concern in the market given the opaque nature of information provision during the negotiation process, coupled with the desire to close deals quickly to benefit from timely synergies.

When seeking to determine the economic impact of time until deal completion on stock performance, we cannot directly employ the magnitude of the coefficients of time and time-squared in the models. The literature agrees that the co-efficient of a quadratic term in a model is not equal to the marginal effect, in contrast to the case of a normal linear regression without any polynomial terms or interaction terms. This applies not only to squared terms, but also to other polynomial terms, as well as interaction terms in any empirical model. This issue is further complicated if the regression is a non-linear one, such as the probit or logit regression [

41]. We, therefore, present a graphical illustration of how time until deal completion affects the acquirer’s stock performance at various durations until deal close in

Figure 2 for the one-month interval. As presented in the predictive margins graph of

Figure 2, there is a clear inverse U-shaped relationship between time until deal completion and stock performance. As time until deal completion increases toward the turning point, the acquirer’s abnormal stock returns increase, but they begin to decrease beyond the extremum. Regarding marginal effects, for deals that close up until the turning point of about 455 days, every additional day adds a positive abnormal return to the firm’s overall stock performance until an extremum, thus, lending support to the due diligence hypothesis. However, beyond the extremum, every additional day adds a negative abnormal return to the stock performance, resulting in a decreasing slope and a decline in performance, supporting the overdue hypothesis.

Concerning the other control variables, our results confirm the literature in many ways. Deals paid for in cash are positively related to subsequent acquirer performance, though not significantly, in our sample. The literature generally finds that deals that are expected to result in large gains for the acquirer and in which the acquirer is confident are paid for in cash to prevent the target’s shareholders from benefitting from the increases in share prices that would result if they were paid for in stock. Differences across industries and geographical locations are associated with negative coefficients, as expected. The coefficient on shareholder protection in the target country is positive, indicating that M&A involving target countries with strong shareholder protection are associated with increases in overall share performance and less risk of expropriation from acquirers’ gains, which strongly aligns with both our intuition and the literature. Given the widespread criticism in the literature of using stock performance alone to measure performance, we present further evidence using the acquirer’s post-deal operational and financial performance.

4.2. Operational Performance

We measure operational performance using the change in turnover as a proxy. Thanos and Papadakis [

42] show that this proxy is used in the accounting literature as an alternative approach to measuring operational performance or efficiency. We expect an increase in turnover for deals that improve the acquirer’s operational performance post-M&A. We run a panel regression controlling for firm fixed effects, as in the model in Equation (10), below:

where

is the sales scaled by total assets of the acquirer or newly merged firm t-years after,

is the time until deal completion,

is the squared term of time until deal completion,

are firm fixed effects used to control for time-invariant heterogeneity among firms, and

is the error term. The control variables are the national- and firm-level and deal-specific variables, as explained above. All variables are defined in

Appendix A. The Wald tests verifying that the quadratic terms in the models are equal to zero are reported. In addition, the turning point of the quadratic relationship between time until deal completion and the dependent variable is reported, as well as the result and implication of the stringent test of quadratic relation, following Lind and Mehlum [

36]. Standard errors are corrected for heteroscedasticity and clustered by firm and year.

The results of this regression are presented in

Table 4 below. The results for one year and three years after deal completion indicate an inverse U-shaped relationship between time until deal completion and operational performance, reinforcing our previous results. The results for two and five years after the deal reject the inverse U-shaped relationship in the stringent test. The corresponding predictive margins and marginal effect graphs for one year after the deal are shown in

Figure 3. The summary (albeit weak) evidence is that the due diligence and overdue hypotheses are complementary and are supported with respect to operational performance.

4.3. Financial Performance

We deepen our analysis of post-M&A performance by employing a measure of financial performance proxied by the change in return on assets (ROA) as measured by the change in earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) scaled by total assets [

42]. We employ a panel regression, as in Equation (11), and control for firm fixed effects and correct standard errors for heteroscedasticity and serial correlation, as above.

where

is the earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) scaled by total assets of the acquirer or newly merged firm t-years after,

is the time until deal completion,

is the squared term of time until deal completion,

are firm fixed effects used to control for time-invariant heterogeneity among firms, and

is the error term. The control variables are the national- and firm-level and deal-specific variables, as explained above. All variables are defined in

Appendix A. The Wald tests verifying that the quadratic terms in the models are equal to zero are reported. In addition, the turning point of the quadratic relationship between time until deal completion and the dependent variable is reported, as well as the result and implication of the stringent test of quadratic relation, following Lind and Mehlum [

36]. The results are presented in

Table 5 and graphically in

Figure 4, below.

The results are shown in

Table 5 support hypotheses 1 and 3 for the time intervals of one, two, and three years post-deal. However, the null of monotone or U-shaped relationship between time and financial performance cannot be rejected for the interval of five years after deal completion. All the foregoing results confirm that the due diligence hypothesis (hypothesis 1) and the overdue hypothesis (hypothesis 3) are complementary given the presence of an inverse U-shaped relationship between time until deal completion and post-M&A performance.

4.4. Likelihood of Failure

We further test our hypotheses by investigating how time until deal completion is related to failure for the acquirer after the deal closes. We consider failure to be an event in which the acquirer is delisted at

t periods post-deal [

43,

44].

First, we present a graph of the failure rates of the firms in our sample in

Figure 5. As the figure shows, there is a substantial rate of failure for acquirers post-M&A in our sample. About one-third of firms fail within five years after the deal. Some studies find post-M&A failure rates of about 70% or 90% [

3], so our estimates are relatively conservative. Such high rates of failure motivate an investigation into the determinants of acquirer failure post-M&A. We, therefore, run a logistic regression with a failure dummy as the dependent variable in Equation (12).

where

f(.) is the logit function.

The results are shown in

Table 6 below. To aid interpretation, the marginal effects associated with the regression are reported in

Table 7, and the corresponding predictive margin graph and marginal effect graph for two years post-deal are provided in

Figure 6. The results in

Table 6 and

Table 7 support the due diligence hypothesis and the overdue hypothesis with respect to the likelihood of failure, as predicted in hypotheses 2 and 4. The results are show a strong U-shaped relationship for the two- and three-year time intervals. For the one-year and five-year intervals; however, the composite null of the stringent test of a U-shaped relationship is not rejected. Overall, the results are shown in

Table 6 and

Table 7 support the U-shaped relationship between time until deal completion and the likelihood of failure. The predictive margins in

Figure 6 conform to the shape of a logit distribution and reveal low and decreasing levels of failure prediction before the turning point, and a sharp increase in failure prediction in the days beyond the optimum, which worsens every day. Moreover, the marginal effect is negative before the turning point, indicating that, before the turning point, each additional day reduces the likelihood of failure (supporting the due diligence hypothesis), but that, after the turning point, the marginal effect is always above zero, though it rises sharply and falls. However, the fact that it remains positive beyond the turning point shows that each additional day beyond the turning point is associated with an increased likelihood of failure, supporting the overdue hypothesis.

Table 6 investigates the effect of time until completion on acquirer’s likelihood of failure post-M&A at various time intervals: One year, two years, three years, and five years after the deal by logistic regression. The dependent variable is a dummy that equals one if the firm is delisted by t periods after the close of the deal, and zero otherwise. All variables are defined in

Appendix A. Industry and year effects are included in all models, and the Wald tests verifying that the quadratic terms in the models are equal to zero are reported. In addition, the turning point of the quadratic relationship of time until deal completion with the dependent variable is reported, as well as the result and implication of the stringent test of quadratic relation, following Lind and Mehlum [

36]. Standard errors are clustered by the firm to deal with serial correlation.

Table 7 reports the marginal effects of the regression results in

Table 6. The dependent variable is a dummy that equals one if the firm is delisted by t periods after the close of the deal, and zero otherwise. All variables are defined in

Appendix A. Standard errors are clustered by the firm to deal with serial correlation.

4.5. Survival Analysis

The logit model presents evidence on how time until deal completion influences the likelihood of failure post-M&A. However, the logit model uses only status information (0 or 1) and does not consider the duration until the status changes. However, the transition intensities, which are cumulative, are worth considering. We, therefore, conduct a survival analysis to investigate how time until deal completion influences how long it takes until the acquirer fails (i.e., is subsequently delisted or is involved in another M&A).

Given that

represents the likelihood of experiencing an event at a point in time

(in this case, M&A failure after the deal closes), the cumulative distribution function associated with observing the event within a time interval (in this case, from deal close until deal failure) is given as

. A simple transformation of the cumulative distribution function gives us the survival function, which is the probability of survival beyond time

, expressed as

. We model the hazard rate, which is the relative likelihood that event failure occurs at time

, conditional on the survival of a subject up to time

. Put intuitively, the hazard rate is the instantaneous rate of failure without regard for the accumulation of hazard up to time

. The result of the survival analysis is shown in

Table 8 based on Equation (13), below.

where f(.) is the underlying distribution of the model, t is the time until failure, and tc is the time until deal completion. The gamma model and log-normal model results are reported with selection criteria based on the AIC and BIC values, shown in Panel B.

The table below shows a survival analysis of the time until the acquirer experiences a failure, defined as being delisted by t periods after the close of the deal. All variables are defined in

Appendix A. Standard errors are corrected for heteroscedasticity and clustered by the firm to deal with serial correlation.

First, a test of the proportional hazard assumption shows that the assumption is violated in our sample, for which reason we do not use the semi-parametric cox-proportional hazard model for our survival analysis. Alternatively, we use parametric models, which assume an underlying distribution of the error term. However, our choice of the underlying distribution is not arbitrary. We employ the AIC and BIC information criterion to select the most suitable model for the parametric model. The results, shown in Panel B of

Table 8, show that the gamma distribution and the lognormal distribution are the best in terms of the assumptions of the underlying distribution; we, thus, present the results related to these two distributions. As can be seen in the reported hazard ratios for both the gamma distribution parametric model and the lognormal distribution parametric model, each additional month before the closing of a deal increases the hazard of experiencing a subsequent failure by 0.015% and 0.0182%, respectively, lending more support to the overdue hypothesis.

4.6. Robustness Checks

We conduct a further investigation to test the robustness of our results. As mentioned, the time to deal completion may not be exogenously determined, but rather endogenously influenced. Specifically, deal closing times tend to differ according to how complex the deal is [

8]); whether it is a cross deal [

9]; whether the target experienced poor performance and is being acquired after bankruptcy [

10,

11]; whether it is a friendly or hostile deal [

12]; whether the acquirer’s stocks are overvalued [

13]; whether the deal occurs during a financial crisis [

14]; and what type of deal advisors are involved [

15].

To control for possible endogeneity that may affect our findings, we re-estimate our regressions related to stock performance, financial performance, and operational performance by employing a two-stage least squares regression. We account for complexity by considering the transaction value; for cross-border deals by using a dummy equal to one when the deal is cross-border; for whether the deal is undertaken during a financial crisis by using a financial crisis dummy; and for the target’s past performance by using a bankruptcy flag dummy. The data are all obtained from the SDC. We also use a stock payment dummy and Tobin’s q to control for possible market valuation effects on the timing of the deal and control for deal advisors’ influence on the deal completion time using the number of acquirer and target advisors (where available). The excluded instruments in our regressions are the number of acquirer advisors and the number of target advisors.

Regarding the exclusion conditions, the number of target and acquirer advisors should not have a direct effect on the acquirer’s post-M&A performance. The type and quality of the acquirer and target advisors should have a direct effect on their performance rather than the number of advisors. We argue that though the kind and number of acquirer and target advisors can potentially influence the performance of the acquirer, it is unlikely that this effect will be direct. The number of acquirer advisors and target advisors should only affect the performance of the acquirer through their influence on how fast and timely the deal is consummated. Although it is not a direct test of the exclusion condition, the Hansen J-Test of over-identifying restrictions with the null that the instrumental variables are valid (i.e., uncorrelated with an error term and the excluded instruments are correctly excluded from the estimated equation) is not rejected. We also conduct endogeneity test for the endogenous regressor and find that the null that the specified endogenous regressors can actually be treated as exogenous is not rejected suggesting that using OLS approach may be more efficient than using the IV approach. This obviously does not augur well for our work.

However, we will like to believe that time until deal completion is still endogenous to tread on the side of caution. Even if time until deal completion were not endogenous, it still works in our favor that the fixed effect regression earlier presented is valid. As mentioned earlier, the literature has indicated that time is endogenously determined, and economic reasoning supports the endogeneity of time until deal completion as the time is affected by many human and discretionary factors while a deal is negotiated, and thus, not exogenously determined. However statistically, we are unable to show the endogeneity of the time variable from the data. We are regardless inclined to argue that the endogeneity of time is valid, and some reasons may attribute for our failure to reject the null of the endogeneity test statistically.

First, our instrument is shown to be weak, which is a limitation of our work. The endogeneity test is found to be invalid under weak instruments, and its power varies depending on instrument strength, an issue extensively discussed in the literature [

45,

46].

Secondly, due to data limitations, we have a lot of empty slots for the number of target advisors and a number of acquirer advisors which reduces our sample size in the IV regressions greatly by more than 70% compared to the fixed effects regressions. This may also partially account for why we fail to reject the test. We are unable to confirm this for sure, given the data limitations and the weakness of our instrument. Thus, the result under the IV regression may be taken with a pinch of salt.

To deal with potential issues caused by the use of a weak instrument, we re-run our regressions using an estimator known to be robust to weak instruments, that is, Fuller’s modified LIML estimation [

47]. We follow Hahn, Hausman, and Kuersteiner in using α = 4 for our Fuller estimation, as they find that it works significantly better than α = 2 [

48]. The Fuller estimation results are available upon request from the authors. We present and discuss our results from the 2SLS, shown in

Table 9,

Table 10, and

Table 11.

The results shown in

Table 9 confirm the validity of our results for the one-, two-, and three-year intervals, though only weakly for the one-year interval. There is an inverse U-shaped relationship between time until deal completion and the acquirer’s stock performance post-M&A for these intervals. For the one-, three-, and six-month intervals, our hypotheses are not supported with respect to post-M&A performance, perhaps due to the loss of many observations caused by a lack of data on the number of acquirer and target advisors.

None of the results for the operational performance, shown in

Table 10, is significant at the 5% level. The only noteworthy observation is that the coefficient on time until deal completion has the expected sign. Regarding financial performance, the results are shown in

Table 11 indicate that both hypotheses 1 and 3 are supported for all time intervals except for the five-year period. Thus, after possible endogeneity concerns are controlled for, our overall results support the two complementary hypotheses, albeit weakly. For the sake of brevity, we only present summarized results of the 2SLS fixed regressions here. The full results will be available upon request for interested readers.

Table 9 investigates the effect of time until completion on acquirer’s stock performance post-M&A at various time intervals by a 2SLS fixed effects regression. For the one- and three-month time intervals, the cumulative abnormal return is used as the dependent variable; for the six-month, one-year, two-year, and three-year intervals, the buy-and-hold abnormal returns is used as the dependent variable. All variables are defined in

Appendix A. Firm fixed effects are included in all models, and standard errors are corrected for heteroscedasticity and clustered by firm and year. The Wald test, U-test, Hansen J test and the endogeneity test results are also reported.

Table 10 investigates the effect of time until completion on acquirer’s operational performance post-M&A by a 2SLS fixed effects regression for various time intervals: One year, two years, three years, and five years after the deal. The dependent variable is the change in turnover of the acquirer from the close of the deal and t years after. All variables are defined in

Appendix A. Firm fixed effects are included in all models, and standard errors are corrected for heteroscedasticity and clustered by firm and year to deal with serial correlation. The Wald test, U-test, Hansen J test and the endogeneity test results are also reported.

Table 11 investigates the effect of time until completion on acquirer’s financial performance post-M&A by a 2SLS fixed effects regression for various time intervals: One year, two years, three years, and five years after the deal. The dependent variable is the change in return on assets of the acquirer from the close of the deal and t years after. All variables are defined in

Appendix A. Firm fixed effects are included in all models, and standard errors are corrected for heteroscedasticity and clustered by firm and year to deal with serial correlation. The Wald test, U-test, Hansen J test and the endogeneity test results are also reported.