Abstract

Environmental sustainability is a major concern of contemporary societies, businesses, and governments. However, there is a lack of knowledge as to how countries can achieve the goal to end poverty, whilst protecting the planet. It is the objective of our study to examine the moderating role of institutional quality on the financial development and environmental quality nexus in South Asia. Our sample consists of panel data of five South Asian countries (India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Pakistan) from 1984 to 2018. We find that financial development increases CO2 emissions in this region, implying that countries in South Asia have utilized financial development for capitalization, instead of improving production technology. Institutional quality moderates the negative impact of financial development on environmental sustainability. An implication of our findings is that efforts to improve institutional quality may help to promote sustainable development in South Asia.

1. Introduction

A clean natural environment is considered an essential element for improving the quality of human life in modern societies. Government and regulatory authorities have a keen interest in the management of natural resources to preserve the ecosystem. Yet, natural resources, in particular fossil fuels and minerals, are essential to economic development since they are key inputs to the production of goods and services. However, the expenditure of natural resources through the combustion of fossil fuels, increases CO2 emission into the atmosphere, a gas that absorbs and emits thermal radiation and is a primary contributor to the so-called ‘greenhouse effect’. In the last four decades, global CO2 emissions have been the main contributor to environmental degradation and climate change risk. Although the share of South Asian countries in global CO2 emissions is currently less than ten percent, it is expected to increase significantly as these economies develop further [1].

Given that climate change poses a significant threat to human life, researchers are increasingly focusing on achieving better understanding of the link between economic growth and environmental degradation. Financial development has been strongly linked to environmental degradation [2]: financial development increases environmental pollution by boosting industrial activity [3]. However, countries with well-developed financial markets tend to have a cleaner environment [4].

Institutional quality—rules of law, risk of expropriation, corruption, quality of bureaucracy—is a less considered factor in terms of the causes of environmental degradation [5,6,7,8,9]. Arguably, environmental quality improves when government institutions are effective enough to enforce environmental standards and regulations that have been adopted [10].

Empirically, the financial development and environmental quality nexus has been examined in a number of developing countries, including Brazil, Russia, India and China (BRIC) countries [11], China [12,13,14], sub-Saharan African countries [15], Turkey [16], Indonesia [17], South Africa [18], Vietnam [19], Middle East and North Africa (MENA) countries [20], and 19 emerging economies [21].

South Asia is characterized by rapid urbanization and population explosion. It has many industries with highly outdated technologies and high carbon-emitting infrastructure. As a result, air, surface and water pollution have increased substantially in this region of the world as it has developed economically. If appropriate measures are not taken to reduce environmental pollution, South Asian countries may have to face severe negative economic consequences as a result of climate change. Nevertheless, only a limited number of studies have examined the financial development and environmental quality nexus in this region, notably India [22,23] and Pakistan [24,25,26]. However, these studies have ignored the influence of institutional quality on environmental quality, even though institutional failure may exacerbate this association. The aim of our study is to fill this gap in the literature.

Our sample covers five countries of South Asia for the period 1984 to 2018: Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Bangladesh. Our panel analysis indicates that financial development causes environmental pollution, consistent with the prevailing literature. Hence, countries in South Asia have utilized financial development for capitalization, instead of improving production technology. Notably, institutional quality moderates the negative impact of financial development on environment quality, suggesting that well-functioning institutions act in enhancing environmental sustainability.

The remaining part of this paper is organized is as follows. Section 2 provides the hypotheses and a short literature review, followed by a discussion of the data and methodology in Section 3. Empirical findings are provided in Section 4, whilst Section 5 provides a conclusion of our findings, including a policy implication and suggestions for future research.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

There is a rich theoretical literature on the relation between financial development and environmental performance. Scholars [4,11,27] argue that financial development helps reduce environmental pollution for the following main reasons: (1) businesses are required to periodically update production technology and equipment in order to lessen production costs as well as improve the market competitiveness of products, which are possible only with adequate financial support. Businesses can achieve this by effectively mitigating their financing constraints through a well-developed financial system; (2) governments promote environment friendly projects, clean energy usage, and overall industrial transformation in order to cope with environment degradation. Financial institutions considering such policy arrangements play an important role as governments can obtain the necessary funds to finance such projects, reducing environmental pollution through improvements in energy infrastructure; (3) firms listed on the stock market are required to disclose all types of information (including environmental information) on a regular basis and are under strict supervision of regulatory authorities. To remain credible, firms need to create and maintain a good image/reputation, such as using environment friendly technologies which helps to reduce environmental pollution.

Grossman et al. [28] argue that the acceleration of economic growth results in higher environmental pollution in the early stage, but in later stages lowers environmental pollution; high emissions of pollutants are the result of high energy usage resulting from economic growth [29]; economic growth and environmental degradation have a causal relation [30].

Energy consumption is a key determinant of environmental pollution [29,31,32]. Rapid growth in the social economy leads to higher energy usage, increasing environmental pollutant emissions [33]. Zhu et al. [34] propose that energy plays a vital role in economic development and poverty reduction and that such countries need to use energy in an effective way and move to clean and renewable energy by adopting an energy development program.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) is also thought to be associated with environmental pollution [31]. The pollution haven hypothesis and the halo effect hypothesis are two perspectives of the relation between FDI and environmental pollution. The pollution haven hypothesis states that developing countries, through non-enforced or relaxed regulation, tend to disregard environmental concerns in order to attract FDI [35]. Contrarily, the pollution halo hypothesis argues that the FDI effect is inverted by introducing low polluting technologies [36]. The empirical literature has reached consensus about the existence of positive linkage between FDI and financial development (SMD) [37,38,39,40]. FDI leads to economic growth and economic growth promotes SMD [41]. Therefore, FDI promotes SMD. Malik and Amjad [42] derive an inference on the role of FDI in promoting aggregate SMD in Pakistan. On the other hand, Heyes et al. [43] argue that air pollution could influence brain health, cognition and risk attitude, resulting in decreased risk tolerance, changed mood and trading behavior of investors. Further, they provide evidence that poor air quality in a stock-market based city causes market prices to diverge from prices based on fundamentals, which results in lower returns.

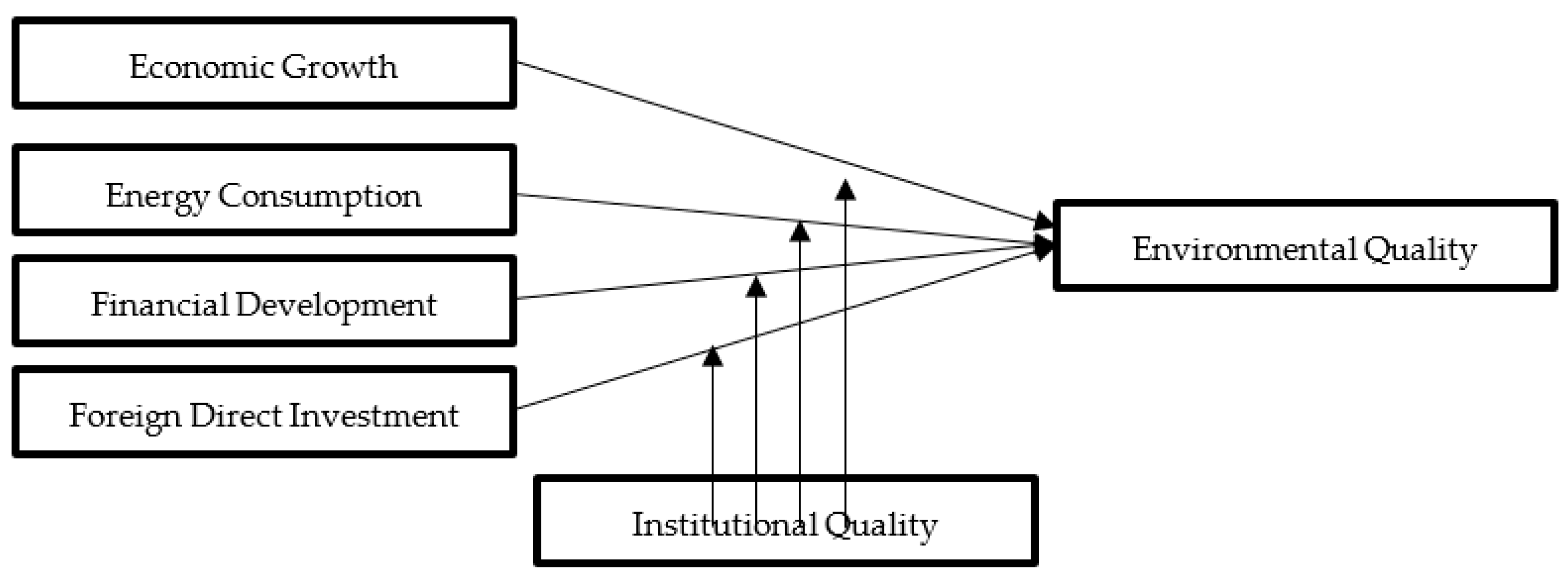

Figure 1 shows the proposed theoretical framework of our study. We consider financial development, institutional quality, foreign direct investment, economic growth and energy consumption as key determinants of environmental quality.

Figure 1.

Proposed theoretical framework.

According to Yuxiang and Chen [13], financial development influences environmental quality in four probable ways, including capitalization, technology, income and regulation effects. In the capitalization effect, the growth of small-scale industries is stimulated by financial development having some benefits, including the reduction in pollution and economies of scale [44]. The technology effect requires the encouragement of environment-friendly projects through financial development [11] and advancements in technology by offering cheaper financing, which in turn reduces pollution through adopting more efficient production processes [45]. On the other hand, technologically advanced firms need more natural resources which may negatively affect environmental quality [46]. In the income effect, it is assumed that long-run economic growth is stimulated by financial development [47], which can have either positive or negative impacts on the environment [48]. The regulation effect implies that financial development, in the presence of environmental regulations, is advantageous for the environment [13]. Firms having ordinance of environmental regulation can protect the environment and can access external financing from banks based on their environmental assessment. This policy is thought to have significantly contributed to improved environmental quality in China [49]. According to Adom et al. [50], financial development negatively affects environmental pollution as it has less scale effects but more technical effects at the macro level. Saidi and Mbarek [21] report negative impact of financial development on environmental pollution. Others [18,51,52] document similar findings.

Considering the weight of the arguments provided above, we predict the following:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Financial development negatively affects environmental quality.

Institutional quality, such as rule of law, quality of bureaucracy, and control of corruption, is an important, although somewhat neglected aspect that may influence environmental quality [5,6,7,8,9,53]. Conversely, institutional failure may lead to degradation of the ecosystems. Well-functioning quality institutions improve the environment even if a country has a low level of income [53]. Environmental quality improves when government institutes are strengthened enough to enforce environmental standards and regulations [10]. Governmental organizations may prioritize factors like legal and political framework, sufficient budgetary resources, feedback mechanisms availability, citizens’ perceived ease of engagement and motivated citizens that boost citizen engagement to create higher value with open government data (OGD) to solve societal problems, which may improve institutional quality [54]. Practitioners and policymakers need to assure the importance of key factors, i.e., user satisfaction, usefulness, efficiency, quality, ease of use, which ultimately enhance institutional performance [55].

Persson et al. [56] argue that at the early stages of economic development, environmental pollution can be reduced through adopting policies for pollution reduction. One such policy to mitigate pollution is a strong financial system along with an efficient institutional structure. Hence, environmental quality improves with future higher income as income growth and environmental regulation go side by side. That is, environmental standards are relaxed at initial stages of economic development but become stronger when the level of development improves [10]. Tamazian and Rao [2] argue and find that both financial development and institutional quality are negatively associated with environmental pollution.

Based on the discussions above, we predict the following:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Institutional quality positively affects environmental quality.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Institutional quality moderates the negative relation between financial development and environmental quality.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data

The sample of our study consists of annual data from five South Asian countries (India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan) over the period of 1984 to 2018. Three South Asian countries (Bhutan, Maldives, and Afghanistan) are excluded from our sample due to unavailability of data. We use the corruption index as the proxy for institutional quality, with the data taken from Table 3B of the International Country Risk Guide (ICRG). Goel et al. [57] use the same proxy in their study to measure institutional quality. We use World Development Indicators (WDI) to obtain data for the remaining macroeconomic variables. WDI is an online database operated by the World Bank. CO2 emissions data are extracted from World Data Atlas.

3.2. Methodology

To test our hypotheses, we estimate the following panel regression model (Equation (1)):

where enqi,t is CO2 emissions (CO2), ecgi,t is economic growth, enci,t is energy consumption, fidi,t is financial development, fdii,t is foreign direct investment, insqi,t is institutional quality and υ is the residual term.

enqi,t = β0 + β1ecgi,t + β2enci,t + β3fidi,t + β4fdii,t + β5insqi,t + β6(ecgi,t * insqi,t) + β7(enci,t * insqi,t) + β8(fidi,t * insqi,t) + β9(fdii,t * insqi,t) + υi,t

Environmental quality (enq) is proxied by per capita CO2 emissions (metric tons per capita) [34,58]. Countries with higher per capita CO2 emissions have lower environmental quality. Environmental degradation and global warming are affected by CO2 emissions at a larger scale in comparison to other greenhouse gases (GHGs), such as sulfur dioxides and nitrogen oxides which are generated by power plants, energy-intensive industries, and transportation [59].

Economic growth (ecg) is proxied by real GDP per capita in US dollars (income) [34]. The intuition is that economic activities, like manufacturing, electricity generation and operation of motor vehicles, boost air pollution.

Energy consumption (enc) is proxied by the per capita kilogram of oil equivalent [33,34]. Arguably, energy consumption has a strong negative impact on the environment. It affects the environment through the burning of fossil fuels, in particular coal.

Financial development (fid) is proxied by the private sector domestic credit, as a percentage of GDP [33,34,58]. Whilst several studies have used M2 or M3, as a percentage of GDP (liquid liabilities), Shahbaz and Lean [60] criticize this measure claiming that these represent liquid liabilities instead of the size of the financial sector. We predict that financial development increases pollution.

Foreign direct investment (fdi) is proxied by foreign direct investment as a percentage of GDP [34]. The net effect of FDI on environmental quality depends upon the prevailing conditions discussed in the pollution haven hypothesis and the pollution halo hypothesis.

In Equation (1), both the independent and dependent variables are represented in logarithmic form. Thus, the β-coefficients show elasticities. For example, β1 is the elasticity of environmental pollution with respect to economic growth, which is anticipated to have a positive sign since pollution is anticipated to increase with economic growth in South Asia.

To test for the moderating effect of institutional quality on CO2 emissions through economic growth (ecg), energy consumption (enc), financial development (fid) and FDI (fdi), we add the following interaction terms to the regression model: (ecgi,t * insqi,t), (enci,t * insqi,t), (fidi,t * insqi,t) and (fdii,t * insqi,t) respectively. We expect the coefficients on each of these interaction terms to be negative and significant. Effective regulatory framework exercised through strong institutions ensures efficient use of energy which decreases environmental pollution [61]. A well established and effective institutional mechanism discourages FDI in contaminating industrial sectors and encourages FDI in environment-friendly and less polluting industries. Variables measurement is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variables measurement.

Ignoring cross-sectional dependence in the estimation may result in loss of efficiency of the estimators, biased test statistics and spurious inferences in hypothesis testing. Consequently, we conduct several cross-sectional dependence tests. The null hypothesis of no-cross-sectional dependence is as follows: Ρij = Corr(νit, νjt) = 0 for I ≠ j, where Ρij is correlation coefficient among the disturbances in cross-sectional units i and j.

4. Empirical Results

Table 2 provides the descriptive statistics of the sample. The mean value of environmental quality measured by CO2 emissions is 0.54, ranging from 0.03 to 2.02 metric tons CO2 per capita. Economic growth per capita has an annual average of 2825.13 US dollars, ranging from 892.92 to 11,738.40 US dollars. Energy consumption per capita ranges from 103.91 to 639.95 kilogram of oil equivalent, with a mean value of 356.14. Financial development, proxied by domestic credit to the private sector as a percentage of GDP, has an average value of 27.73, ranging from 8.49 to 66.92. FDI is relatively low for our sample of South Asian economies, with an average value of just 0.74 percent, ranging narrowly between 0 and 3.68 percent. Finally, institutional quality proxied by the corruption index has a mean value of 2.25 and varies between 0.10 and 4.00. A score of 4 represents very low corruption risk, whilst a score of 0 represents very high corruption risk.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 3 shows the Pearson pairwise coefficient matrix of the regression variables. Notably, environmental quality proxied by CO2 emissions (enq) has a high and positive correlation with energy consumption (enc) and financial development (fid), as expected. CO2 emissions is also positively correlated with economic growth (ecg) and FDI (fdi). The correlation between environmental quality and institutional quality (insq) is also positive. Based on the relatively weak correlations between the dependent variables, multicollinearity is unlikely to be a major concern in our regression analysis.

Table 3.

Pearson correlation matrix of key variables.

Table 4 provides the results of our cross-sectional dependence tests. The table shows that the null hypothesis of no-cross-sectional dependence is rejected in all tests, indicating the existence of cross-section dependence in the data. To overcome this problem, we estimate the model by applying the generalized least squares (GLS) technique. In our model, the number of explanatory variables considered exceeds the number of cross-sectional units. As a result, we estimate the model using country fixed-effects.

Table 4.

Cross-section dependence (CD) tests.

The regression results are reported in Table 5. Economic growth (ecg) has a statistically significant positive association with CO2 emissions (column 1), suggesting that economic growth in South Asian economies is at the cost of the environment, as predicted. Our finding is inconsistent with the phenomenon of “decoupling of economic growth and CO2 emissions” [62,63]. We also find that energy consumption (enc) is positively and significantly associated with CO2 emissions (see columns 1 to 6). This finding supports the proposition that energy consumption is a key driver of CO2 emission.

Table 5.

Panel regression results for CO2 emissions (enqit).

The coefficient of financial development (fid) is statistically significant and positive (column 1). Thus, financial development is associated with lower environment quality in South Asian countries, as predicted. This result is robust to alternative specifications and consistent with the estimates and inferences of the literature for developing economies [14,26,64]. The interpretation is that financial development is used in developing countries for capitalization, i.e., to boost the growth of small and medium scale industries. Small and medium enterprises have fewer advantages of economies of scale (in the usage of resources) and pollution reduction. So, pollution increases as a result of financial development. Our findings show that in South Asia, the technology effect is outweighed by the capitalization effect, suggesting that environment friendly and fuel-efficient technologies are not the priority of the financial sector for the provision of finance. To sum up, our results do not provide any evidence for the proposition that financial development reduces pollution through the dominance of the technology effect. This finding deviates from Boutabba [22] for India, and Abbasi and Riaz [25] for Pakistan, who report that financial sector development enhances environmental quality.

Our main variable of interest is institutional quality. Institutional quality (insq) has a negative and statistically significant association with CO2 emissions, suggesting that strong institutions boost environment performance, whilst weak institutions are associated with environmental harm. Further, all the interaction terms (with institutional quality) are negative and statistically significant. Taken together with the findings detailed above, strong institutions lessen the adverse impacts of economic growth, energy consumption and financial development on the environment. This provides support for the regulation effect hypothesis, i.e., with the implementation of (environmental) standards, the trade-off between financial development and environmental quality lessens. Hence, in the presence of strong institutions, financial markets are more likely to provide capital to environment-friendly business projects. Therefore, the negative impact of financial development on environmental quality should be balanced with highly effective institutions so as minimize harm to the environment.

Foreign direct investment (fdi), our proxy of financial openness, is negatively associated with CO2 emissions. Our results provide some support for the “pollution halo hypothesis”, in that the inflow of foreign investment helps to reduce pollution by transferring energy-efficient technology to the host country [11,65]. However, we should be careful in terms of attributing causation to this relationship as it is possible that more polluted countries attract less FDI. Our results are contrary to those of Cole et al. [66] for their large sample of 94 countries for the period of 1987 to 2000, who find that the inflow of FDI leads to environmental harm.

The coefficient of the interaction of FDI with institutional quality is negative and is statistically significant. This finding suggests that, jointly with effective institutional infrastructure, FDI can play an effective role in reducing CO2 emissions. This reinforces the complementary role of the regulatory framework and effective institutional infrastructure in developing countries in terms of boosting environmental protection [67]. Knowledge incentive economies and technology driven innovation may provide a benchmark and is one of the key challenges towards sustainable growth from a global perspective [68].

Overall, our model has high explanatory power. The Durbin-h test results, used to diagnose autocorrelation, show that all statistical values of Durbin-h test are higher than 1.96, indicating no evidence of the presence of autocorrelation in the model. The F-statistics shows that all independent variables are jointly significant. The validity of the instruments has been checked by employing the J-test, also called ‘Sargan J-test’. The p-values for the J-statistics are high which suggests that the instruments are valid.

Next, we examine the efficiency and scale effect of stock market development and financial sector development, following Zhang [14]. Efficiency effect is proxied by credit to the private sector as a percentage of GDP, while the scale effect of financial sector development is proxied by total credit as a percentage of GDP.

Table 6 shows that both indicators of financial sector development, i.e., total credit (tc) as a percentage of GDP and private credit (pc) as a percentage of GDP, increase CO2 emissions. This is in line with earlier findings that financial development negatively affects environmental quality in South Asia. Our results are inconsistent with that of Abbasi and Riaz [25] who find a negative impact of total credit, as a percentage of GDP, on CO2 emissions in Pakistan. The estimates presented in Table 6 column (1) are similar to those reported in Table 5 column (1). The efficiency effect of financial sector development outweighs the scale effects as indicated by the size of the coefficients. Moreover, the efficiency effect has high statistical significance as compared to the scale effect. These finding contradict with those of Zhang [14] for China.

Table 6.

Scale and efficiency effects (enqit).

Stock market capitalization (mc) has a positive coefficient and is statistically significant, while the estimated coefficient of stock traded (st) has a negative coefficient. These results imply that CO2 emissions increase with scale effects of stock market development, while CO2 emission decrease with the efficiency of stock markets, consistent with the findings of others [14,25]. Column 5 presents the joint effect of the financial sector variables on CO2 emissions. The coefficient of each test variable is consistent both in terms of their sign and statistical significance. However, the coefficient of private credit is now statistically insignificant, plausibly a result of multicollinearity as this variable is highly correlated to total credit, as show in Table 7.

Table 7.

Correlation matrix of financial development variables.

5. Conclusions

We examine the moderating effect of institutional quality on the financial development and environmental quality nexus in South Asia. We use panel data and conduct empirical analysis over the period from 1984 to 2018. We find that financial development is used for capitalization purposes, not for directing the use of clean energy, leading to increased environmental degradation. Thus, financial development deteriorates the environment in South Asia, as proxied by per capita CO2 emissions. FDI, a measure of financial openness, reduces CO2 emissions. This relation offers some support for the pollution halo hypothesis, which specifies that FDI brings technological advancements to the host country, helping in reducing environmental pollution in South Asia.

We find institutional quality is a key factor in improving the environment. Institutional quality moderates the adverse effects of economic growth, energy use, and financial development on the environment. In sum, weak institutions damage the environment, whereas strong institutions improve the environment in South Asia. In terms of policy implications, we believe that sustainable development, i.e., economic growth while preserving the quality of the environment, can be achieved in South Asian countries through strengthening of their institutions. For this, governments should create public awareness about the environment, introduce effective environmental monitoring, and strictly enforce environmental laws and systems, using pro-active policies.

Our study has several limitations. First, we employ country-level data only. It may be worthwhile to extend the empirical analysis at the disaggregate level using firm-level data so as to gain insights into how financial development can encourage firms to use efficient technologies that are environmentally friendly. Second, we used a single indicator of institutional quality. Future studies may develop a more comprehensive composite index of institutional quality using multiple indicators related to governance, regulatory framework and enforcement. Finally, our proxy of financial development is credit to the private sector, future research could use a broader proxy for access to capital market finance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.I.H. and M.I.C.; methodology, P.V. and T.T.; software, A.M.; validation, A.I.H. and P.V.; formal analysis, A.I.H. and M.I.C.; investigation, A.M. and A.I.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.I.H. and M.I.C.; writing—review and editing, P.V. and T.T.; supervision, A.I.H. and P.V.; project administration, A.I.H., T.T. and M.I.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Olivier, K.M.; Schure, J.G.J.; Peters, J.A.H.W. Trends in Global CO2 and Total Greenhouse Gas Emissions: 2017 Report; PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tamazian, A.; Rao, B.B. Do economic, financial and institutional developments matter for environmental degradation? Evidence from transitional economies. Energy Econ. 2010, 32, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadorsky, P. The impact of financial development on energy consumption in emerging economies. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 2528–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S.; Laplante, B.; Mamingi, N. Pollution and capital markets in developing countries. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2001, 42, 310–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.A. Corruption, income and the environment: An empirical analysis. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 62, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutt, K. Governance, institutions and the environment-income association: A cross-country study. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2009, 11, 705–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, L.S.; Choong, C.K.; Eng, Y.K. Carbon dioxide emission, institutional quality, and economic growth: Empirical evidence in Malaysia. Renew. Energy 2014, 68, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.H.; Law, S.H. Social capital and CO2 emission—Output relations: A panel analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 29, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.H.; Law, S.H. Institutional quality and CO2 emission—Trade relations: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. S. Afr. J. Econ. 2016, 84, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yandle, B.; Bhattarai, M.; Vijayaraghavan, M. Environmental kuznets curves: A review of findings. methods, and policy implications. Property and Environment Research Centre (PERC), Research study 02-1 update. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.618.3163 (accessed on 15 June 2019).

- Tamazian, A.; Chousa, J.P.; Vadlamannati, K.C. Does higher economic and financial development lead to environmental degradation: Evidence from BRIC countries. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalil, A.; Feridun, M. The impact of growth, energy and financial development on the environment in China: A cointegration analysis. Energy Econ. 2011, 33, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuxiang, K.; Chen, Z. Financial development and environmental performance: Evidence from China. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2011, 16, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.J. The impact of financial development on carbon emissions: An empirical analysis in China. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 2197–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-mulali, U.; Sab, C.N.B.C. The impact of energy consumption and CO2 emission on the economic growth and financial development in the Sub Saharan African countries. Energy 2012, 39, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, I.; Acaravci, A. The long-run and causal analysis of energy, growth, openness and financial development on carbon emissions in Turkey. Energy Econ. 2013, 36, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Hye, Q.M.A.; Tiwari, A.K.; Leitão, N.C. Economic growth, energy consumption, financial development, international trade and CO2 emissions in Indonesia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 25, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Tiwari, A.K.; Nasir, M. The effects of financial development, economic growth, coal consumption and trade openness on CO2 emissions in South Africa. Energy Policy 2013, 61, 1452–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mulali, U.; Saboori, B.; Ozturk, I. Investigating the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis in Vietnam. Energy Policy 2015, 76, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omri, A.; Daly, S.; Rault, C.; Chaibi, A. Financial development, environmental quality, trade and economic growth: What causes what in MENA countries. Energy Econ. 2015, 48, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi, K.; Mbarek, M.B. The impact of income, trade, urbanization, and financial development on CO2 emissions in 19 emerging economies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 12748–12757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutabba, M.A. The impact of financial development, income, energy and trade on carbon emissions: Evidence from the Indian economy. Econ. Model. 2014, 40, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Mallick, H.; Mahalik, M.K.; Loganathan, N. Does globalization impede environmental quality in India? Ecol. Indic. 2015, 52, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M. Does financial instability increase environmental degradation? Fresh evidence from Pakistan. Econ. Model. 2013, 33, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, F.; Riaz, K. CO2 emissions and financial development in an emerging economy: An augmented VAR approach. Energy Policy 2016, 90, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javid, M.; Sharif, F. Environmental Kuznets curve and financial development in Pakistan. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, F.; Shahbaz, M.; Ahmed, A.U.; Alam, M.M. Financial development and energy consumption nexus in Malaysia: A multivariate time series analysis. Econ. Model. 2013, 30, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G.M.; Krueger, A.B. Environmental Impacts of a North American Free Trade Agreement; National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper No. 3914: Mexico, USA; NBER: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, J.B. CO2 emissions, energy consumption, and output in France. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 4772–4778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Wang, B. The moderating role of corruption between economic growth and CO2 emissions: Evidence from BRICS economies. Energy 2018, 148, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.F.; Tan, B.W. The impact of energy consumption, income and foreign direct investment on carbon dioxide emissions in Vietnam. Energy 2015, 79, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Kubota, J. The association between urbanization, energy use and carbon emissions: Evidence from a panel of Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1368–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, J.; Fan, X.; He, P.; Xiong, H.; Shen, H. The effects of energy consumption, economic growth and financial development on CO2 emissions in China: A VECM Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Duan, L.; Guo, Y.; Yu, K. The effects of FDI, economic growth and energy consumption on carbon emissions in ASEAN-5: Evidence from panel quantile regression. Econ. Model. 2016, 58, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pao, H.T.; Tsai, C.M. Multivariate Granger causality between CO2 emissions, energy consumption, FDI (foreign direct investment) and GDP (gross domestic product): Evidence from a panel of BRIC (Brazil, Russian Federation, India, and China) countries. Energy 2011, 36, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarsky, L. Havens, halos and spaghetti: Untangling the evidence about foreign direct investment and the environment. Foreign Direct Invest. Environ. 1999, 13, 47–74. [Google Scholar]

- Tsagkanos, A.; Siriopoulos, C.; Vartholomatou, K. Foreign direct investment and stock market development: Evidence from a ‘new’ emerging market. J. Econ. Stud. 2019, 46, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffus, M.W. FDI and stock market development in selected Latin American countries. Int. Financ. Rev. 2005, 5, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumaré, I.; Tchana Tchana, F. Causality between FDI and financial market development: Evidence from emerging markets. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2015, 29, S205–S216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Iqbal, N.; Ahmed, Z.; Ahmed, M.; Ahmed, T. The role of FDI on stock market development: The case of Pakistan. J. Econ. Behav. Stud. 2012, 4, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, M.A.; Tweneboah, G. Foreign direct investment and stock market development: Ghana’s evidence. Int. Res. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 26, 178–185. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, A.I.; Amjad, S. Foreign direct investment and stock market development in Pakistan. J. Int. Trade Law Policy 2013, 12, 226–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyes, A.; Neidell, M.; Saberian, S. The Effect of Air Pollution on Investor Behavior: Evidence from the S&P 500; National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper w22753: New York, USA; NBER: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren, T. A real options approach to abatement investments and green goodwill. Environ. Res. Econ. 2003, 25, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbaroğlu, G.; Karali, N.; Arıkan, Y. CO2, GDP and RET: An aggregate economic equilibrium analysis for Turkey. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 2694–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanstad, A.H.; Roy, J.; Sathaye, J.A. Estimating energy-augmenting technological change in developing country industries. Energy Econ. 2006, 28, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, R.I. Money and Capital in Economic Development; Brookings Institution, Inc.: Washington, DC, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, G.M.; Krueger, A.B. Economic-growth and the environment. Q. J. Econ. 1995, 110, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Environmental Performance Review of China. OECD Working Party on Environmental Performance. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/environment/country-reviews/37657409.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Adom, P.K.; Kwakwa, P.A.; Amankwaa, A. The long-run effects of economic, demographic, and political indices on actual and potential CO2 emissions. J. Environ. Manage. 2018, 218, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaidi, S.A.H.; Zafar, M.W.; Shahbaz, M.; Hou, F.J. Dynamic linkages between globalization, financial development and carbon emissions: Evidence from Asia Pacific economic cooperation countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, E.; Seker, F. The influence of real output, renewable and non-renewable energy, trade and financial development on carbon emissions in the top renewable energy countries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 60, 1074–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panayotou, T. Demystifying the environmental Kuznets curve: Turning a black box into a policy tool. Environ. Dev. Econ. 1997, 2, 465–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwanto, A.; Zuiderwijk, A.; Janssen, M. Citizen engagement with open government data: Lessons learned from Indonesia’s presidential election. Transform. Gov. People Process Policy 2020, 14, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Grover, P.; Kar, A.; Ilavarasan, P. Review of performance assessment frameworks of e-government projects. Transform. Gov. People Process Policy 2020, 14, 31–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, T.A.; Azar, C.; Lindgren, K. Allocation of CO2 emission permits—Economic incentives for emission reductions in developing countries. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 1889–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.K.; Herrala, R.; Mazhar, U. Institutional quality and environmental pollution: MENA countries versus the rest of the world. Econ. Syst. 2013, 37, 508–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Ma, X. The impact of financial development on carbon emissions: A Global Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Sun, T.; Wang, J.; Li, X. Modeling the nexus between carbon dioxide emissions and economic growth. Energy Policy 2015, 86, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Lean, H.H. Does financial development increase energy consumption? The role of industrialization and urbanization in Tunisia. Energy Policy 2012, 40, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessens, S.; Feijen, E. Financial Sector Development and the Millennium Development Goals; WB Working Paper, World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; WP/No. 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Decoupling China’s carbon emissions increase from economic growth: An economic analysis and policy implications. World Dev. 2000, 28, 739–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutch, J. Decoupling economic growth and carbon emissions. Joule 2017, 1, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Solarin, S.A.; Mahmood, H.; Arouri, M. Does financial development reduce CO2 emissions in Malaysian economy? A time series analysis. Econ. Model. 2013, 35, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Richard, P. Environmental Kuznets curve for CO2 in Canada. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1083–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.A.; Elliott, R.J.R.; Fredriksson, P. Endogenous pollution havens: Does FDI influence environmental regulations? Scand. J. Econ. 2006, 108, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chousa, J.P.; Khan, H.A.; Melikyan, D.; Tamazian, A. Assessing institutional efficiency, growth and integration. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2005, 6, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytras, M.D.; Daniela, L.; Visvizi, A. Knowledge-Intensive Economies and Opportunities for Social, Organizational, and Technological Growth; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).