A Model for the Sustainable Management of Enterprise Capital

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Sources and Methods

3. Results—Model for Sustainable Management of Capitals Based on the Efficiency and Effectiveness of Capitals

- The basic task for an enterprise is to realize strategic and operational goals with the highest possible effectiveness, understood as striving to achieve a point of balance. In other words, an enterprise realizes a goal or goals, and thus should be effective and, at the same time, strive to achieve balance between the capitals, i.e., strive to be as effective as possible. The two ideas—efficiency (in realizing goals) and effectiveness (balance between the capitals)—are the basic principles that shall guide every manager. These principles, realized simultaneously, lead to success and happiness and prove the development of the enterprise. In practice, this means that the actions undertaken by the managers and the economic condition of the enterprise will be assessed based on efficiency (in realizing goal(s)) and effectiveness (the level of balance between the capitals within the enterprise).

- The management of an enterprise is an ongoing process of striving to realize a goal or goals and balancing the level of the capitals within the enterprise. The managers must realize that the efficiency in reaching goals and effectiveness (balance between capitals) often contradict one another. The more efficient the enterprise, the greater the extent to which we succeed in reaching the planned goal or goals. The more effective an enterprise, the quicker the managers will reach the point of balance between the capitals, and the longer the managers will maintain the values of capitals near the balance point. The balance between the company’s capitals should in no case be equated with equal monetary value; balance usually occurs between the capital of different monetary value.

- The monetary values of capitals are subject to constant change. Hence, in practice, management consists of increasing or decreasing the level of a given capital by adjusting its level to the level of other capital, or by adjusting the level of other capital to changes that occurred in one of them. There may also be a situation when the increase in capital(s) does not make it necessary to react with other capital(s), as their level was already higher before. The balance point between the company’s capitals is, at the same time, the maximum efficiency of the company, but because the level of individual capitals is constantly changing, the balance point reached is temporary. For this reason, sustainable capital management is an ongoing process.

- Capitals of an enterprise interact with each other regardless of any actions taken by managers. An increase or a decrease in one capital causes an increase or a decrease of the other capitals, but this is not a general rule. One can imagine a reverse situation, where an increase or a decrease in the level of one capital causes an increase or a decrease in another capital or capitals. The number of capitals and qualifying individual components to it is a matter for the managers. It is important that the number and allocation of components to individual capitals be maintained in the long run, because of the possibility and purposefulness of comparing effects over time. Of much importance in that respect are well-functioning computer programs, leaving the managers, however, with a certain level of flexibility, subject to the requirement indicated in the sentence above, concerning the stability within a certain period of time.

- Lack of balance between capitals is constant. The reasons that cause the lack of balance between capitals may be very different. It would be difficult to classify them into one of the following groups:

- -

- lack of balance resulting from the realization of the goals of an enterprise;

- -

- lack of balance as a result of changes in the environment (change in laws, activity of the competing companies, change in customer preferences, new technologies, change of the percentage rate, etc.);

- -

- lack of balance resulting from the changes within an enterprise.

- We can calculate the progress of reaching the equilibrium point in many ways. It can be expressed, e.g., by the quotient of the sum of differences between the current values of individual capitals and the optimal values of those capitals, ensuring the equilibrium of capitals by the number of capitals included in the calculations. For management purposes, of much importance would be the ratios of the mean percentage difference between capitals and weighted capital differences.

- 1.

- The weighted capital difference ratio has only a slightly more complicated structure:Source: [38].

- 2.

- Only these two factors together inform us about the condition of the enterprise because, while the second one is good for characterizing its overall efficiency, the first one detects large errors on individual capitals, even those with the lowest value at the moment. Such measurements can even be made every day, however, such a high frequency is not needed for the day-to-day management of the enterprise. It can be expected that, in practice, the measurements would be carried out on a monthly, quarterly, and annual basis. Throughout the study, it was possible to develop a mathematical approach towards the discussed concept in the form of two coefficients: the average percentage difference of capitals and weighted capital differences.

- 3.

- The definition of an enterprise is extended. In sustainable management, an enterprise is defined as a set of capitals designated for the efficient realization of goal(s) in striving to achieve effectiveness, or—in broader terms—an enterprise is defined as a set of capitals: tangibles, financial capital, structural capital, market capital, human capital, and social capital, designated for the efficient realization of goal(s) in striving to achieve effectiveness.

- 4.

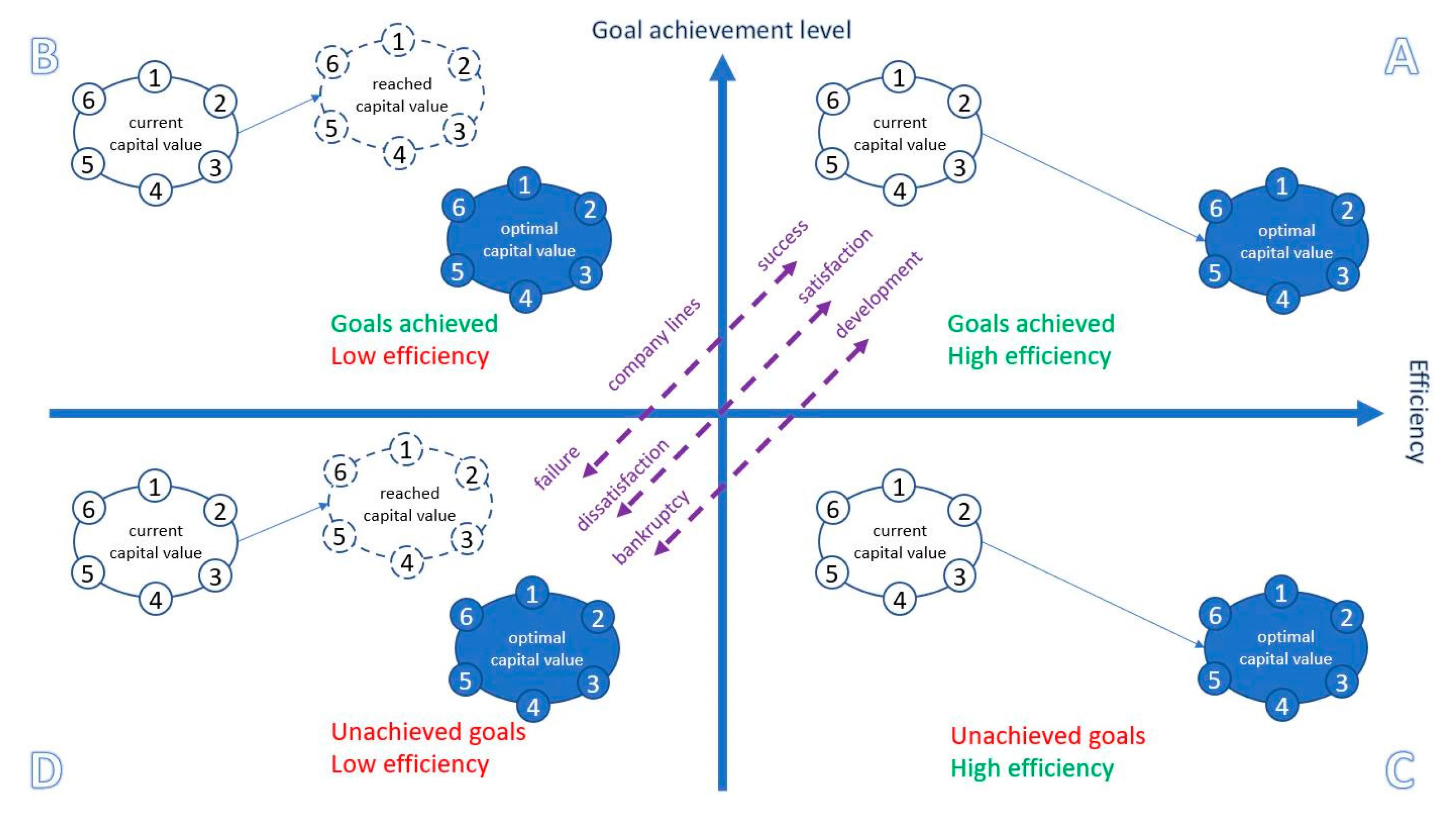

- Graphically, in a simplified way, we may present the process of enterprise management as moving along two lines indicating the level of the realization of goal(s) and reaching the point of balance (accumulation of capitals) between capitals within an ABCD matrix (Figure 1).

- 5.

- The best effects in management are achieved when the enterprise is in box A, when it realizes a goal (e), with the largest possible concentration of capitals (tangibles, structural capital, financial capital, market capital, human resources, and social capital). Such a situation ensures success and happiness.

- 6.

- Box B presents a situation where the enterprise realizes goals, but its effectiveness is at a low level of balance between capitals. Not adjusting the level of the capitals may involve not using them (waste) and incurring unnecessary costs. We should point out the fact that, although the failure to use or improper use of tangibles and structural capital is clearly noticeable, the failure to use or improper use of market and financial capitals is noticeable as well, but in practice, we usually pay less attention to it, while the worst situation occurs in the cases of human and social capital. These are the so-called hidden capitals, and they are rarely measured; usually, managers get partial or incidental information in that respect.

- 7.

- Box C seems a little worse (although this depends on the strategy and the priorities of the owners) than box B, because, although the enterprise remains effective (is able to balance capitals), it does not realize goals. This hinders the development of the enterprise, not to mention the legal, financial, or personnel consequences related to the failure in realizing goal(s).

- 8.

- The worst situation occurs in box D. This means both the failure to realize goal(s) and low effectiveness of capitals. In consequence, this means not only a failure, but it may be the reason of a crisis, or even a bankruptcy. Surely enough, if an enterprise lands in that situation, it is a sign that it is in need of radical changes.

- 9.

- The lines in the model only show direction, and have a symbolic character. In reality, every enterprise moves along the line from development to bankruptcy, but the line is often a curve, and it loops often. Anyway, in reality, an enterprise does not tend to move from point A to D, or vice versa. We can say that the realization of goals very often spoils the balance between capitals, thus an enterprise is first located in box B (e.g., realizes an investment) and only later starts to care about the balance between the capitals, although it would be ideal if efficiency (realization of goals) could be combined with effectiveness (balance between the capitals).

- 10.

- Sustainable management is not only a balance between the capitals, but also between the capitals and the goals. To put it another way, at the stage of planning goals, it should be taken into account to what extent the realization of the goals will cause a lack of balance between capitals, whether it is possible, in what time frame, and with how much effort and resources should capitals be balanced, as the realization of the goals progresses.

- 11.

- Also of key importance for sustainable management of capitals was the development of principles for the measurement of individual capitals, not only of their level, but also of their financial value. The experience with measurements has indicated that the simplest methods are the most effective, even if as accurate as possible. In the future, it would be necessary to develop special IT software for the effective management of capitals, in particular for capital balancing.

4. Discussion

- In the management model presented above, there is a clear distinction between goals and effects. A goal should not involve an economic effect, it is only a result of realizing a goal. A goal may relate to, e.g., market, technology, ecology, or society. In the era of a pandemic, a goal may be, e.g., to ensure the presence of the staff or the timely payment of liabilities. On the other hand, the economic condition of a company should be reflected by capital effectiveness, not related directly to the extent to which the goals are realized.

- Six capitals may be managed so that their optimal value may be shaped, thus striving at reaching the point of balance. For the first time, the managers would be able to see and compare the value of all capitals that contribute to the effects of the company’s activity. In particular, this involves unnoticed and under-appreciated human resources and social capital. Comparing their values and relationships with other capitals will help the managers realize their importance for the effects; it will also show how important it is to keep the balance between the capitals.

- Profit is not a measurement optimizing the use of resources (capitals) within an enterprise. The same level of revenues may be achieved in an enterprise in a number of ways [51]. Striving to achieve revenues at all costs may result in waste of resources, not only of natural resources, but also of human resources, for example. This is the biggest advantage of the described model in comparison with traditional management. One of the basic assumptions within the model is the optimization (mutual adjustment) of the level of six capitals, including human, social, and structural (organizational) capital, and the integration of efficiency in realizing goals with effectiveness. We thus avoid wasting capitals, irrespective of the way in which we would like to reach the point of balance. Problems, such as the social responsibility of a business, treated sometimes as an addition that should be present for goodwill reasons, is becoming an integral part of management.

- Revenues may quite easily be used instrumentally. An example of instrumental use of profit can be an international company within the holding structure, which can easily bring profits to a country with lower taxes, e.g., by maximizing the remuneration of suppliers from another holding company located abroad. On the other hand, municipal enterprises having the characteristics of public utility, in particular when they are owned by the municipalities (in the countries of continental Europe), must shape the profit in such a way that it should not be too big, as managers will be accused of fixing an excessively high level of prices of their services for the dwellers. The revenues cannot be too low either, as this may indicate bad management. Many researchers, in order to name similar phenomena, use the term revenue manipulation [52]. Can you manipulate the extent of realizing a goal or can you manipulate the balance between capitals? The answer is probably yes, which may result, e.g., from the imperfection of capital pricing, but it cannot be used instrumentally for lowering taxes (as this is not why we calculate taxes), and for transferring the profits.

- We do not really know the answer to a question—is the profit gained by the enterprise as a result of the work of the management board and of the employees or of other internal or external circumstances? It may happen that the management board and the employees do a good job, but, because of various circumstances, the enterprise will gain no revenues. Reversely, there are enterprises where, at least within a short period of time, the management board would do nothing or would even make mistakes, and there will be profits. The revenues, as a category, may thus not be a basis for assessing the work of the management board, or at least, it may not be the only indicator. In the case of the model for the sustainable management of capitals, one can quite clearly separate the assessment of the condition of the enterprise, in particular the impact of external factors, beyond the manager’s control, from the assessment of the manager’s work as such.

- The revenues themselves, as a measurement used to assess the company’s condition, may be misleading and decrease awareness. Revenues are not always tantamount to the correct use of capitals, e.g., social capital or human resources. There might be a situation when there is a profit, but the company has no financial liquidity or is excessively indebted, and the repayment of debts exceeds the company’s financial capacity. That is why, in the practice of financial analysis, there is a need to verify at least several or approximately a dozen different indicators, and the calculations must be done many times within certain periods of time in order to get the answer to the question—is the situation getting better or worse? A problematic issue is comparing the profit of an enterprise with other enterprises in the industry—to a group of enterprises or even a single enterprise, potentially being a leader in its industry. Anyway, a large number of ratios are to be calculated at all times, and we should remember that, in practice, there is no such thing as an optimal level of a given indicator. In the proposed model, apart from the extent to which the goals are realized, there are only two more indicators, generally reflecting the company’s economic condition.

- Revenue in enterprises is calculated by the accountants and financial analysts. Their point of honor is often that the numbers are consistent with each other. However, this accuracy and attention to detail is needed for tax payments, but unnecessary for enterprise management. In financial prognosis in particular, because of an unlimited number of circumstances and significant changeability of the surrounding circumstances, the most important managerial decisions, although based on financial calculations, are taken based on the experience of the managers and even based on intuition. Of much importance is also the managers’ willingness to take risk.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hawley, F.B. Enterprise and Profit. Q. J. Econ. 1900, 15, 75–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, F.B. The Controversy about the Capital Concept. Q. J. Econ. 1908, 22, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckerath, H. MacGregor’s Enterprise Purpose and Profit. Q. J. Econ. 1936, 50, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, J.B.; Davis, E.W.; Stacey, R.J. Performance measurement systems, incentive reward schemes and short—termism in multinational companies: A note. Manag. Account. Res. 1995, 6, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowther, D.; Davies, M.; Cooper, S. Evaluating Corporate Performance: A Critique of Economic Value Added. J. Appl. Account. Res. 1998, 4, 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Coram, B. Marx’s Theory of Profit: A critique. J. Politics 1983, 18, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossman, K.; Lange, T. Business as Usual? Ambitions of Profit Maximization and the Theory of the Firm. J. Interdiscip. Econ. 2006, 17, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berle, A.A.; Means, G.C. The Modern Corporation and Private Property; MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, E.T. Limits to the growth and size of firms. Am. Econ. Rev. 1955, 45, 531–543. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, E.T. Foreign investment and the growth of the firm. Econ. J. 1956, 66, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, E.T. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm; Basil Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, E.T. The growth of the firm: A case study: The Hercules Powder Company. Bus. Hist. Rev. 1960, 34, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marris, R. A Model of the “Managerial” Enterprise. Q. J. Econ. 1963, 77, 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marris, R. The Economic Theory of Managerial Capitalism; MacMillan: London, UK, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Koutsoyiannis, A. Modern Microeconomics; MacMillan: London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Baumol, W.J. Business Behaviour, Value and Growth; MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Sandmeyer, R.L. Baumol’s Sales-Maximization Model: Comment. Am. Econ. Rev. 1964, 54, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar]

- Haveman, R.; Bartolo, B. The Revenue Maximization Oligopoly Model: Comment. Am. Econ. Rev. 1968, 58, 1355–1358. [Google Scholar]

- Dobson, S.; Maddala, G.S.; Miller, E. Microeconomics; McGraw-Hill Book Company Europe: Berkshire, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, O.E. Managerial Discretion and Business Behaviour? Am. Econ. Rev. 1963, 53, 1032–1057. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, O.E. The Economics of Discretionary Behaviour: Managerial Objectives of the Theory of the Firm; Englewood Cliffs, Prentice-Hall Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, O.E. Corporate Control and Business Behavior: An Inquiry into the Effects of Organization Form on Enterprise Behavior; Prentice Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T. Business Economics and Managerial Decision Making; John Wiley and Sons: West Sussex, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H.A. A behavioural Model of Rational Choice. Q. J. Econ. 1955, 69, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H. Models of Man, Social and Rational: Mathematical Essays on Rational Human Behavior in a Social Setting; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H. Theories of Decision-Making in Economics and Behavioral Science. Am. Econ. Rev. 1959, 49, 253–283. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H. Rational Decision Making in Business Organizations. Am. Econ. Rev. 1979, 69, 493–513. [Google Scholar]

- Cyert, R.M.; March, J.G. A Behavioural Theory of the Firm, Englewood Cliffs; Prentice-Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Petit, T.A. A Behavioral Theory of Management. Acad. Manag. J. 1967, 10, 341–350. [Google Scholar]

- Machlup, F. Corporate Management, National Interest, and Behavioral Theory. J. Political Econ. 1967, 75, 772–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katona, G. On the Function of Behavioral Theory and Behavioral Research in Economics. Am. Econ. Rev. 1968, 58, 146–149. [Google Scholar]

- Argote, L.; Greve, H.R. A Behavioral Theory of the Firm: 40 Years and Counting: Introduction and Impact. Organ. Sci. 2007, 3, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greve, H.R. A Behavioral Theory of Firm Growth: Sequential Attention to Size and Performance Goals. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 476–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, T.C.; Lovallo, D.; Fox, C.R. Behavioral Strategy. Strateg. Manag. J. 2011, 32, 1369–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, I. A Behavioral Theory of Market Expansion Based on the Opportunity Prospects Rule. Organ. Sci. 2012, 23, 1008–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besley, T.; Ghatak, M. Profit with Purpose? A Theory of Social Enterprise. Am. Econ. J. 2017, 9, 19–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jędrych, E.; Klimek, D. Social Capital in the Company (Meat and Vegetable Processing Industry). Econ. Sci. Agribus. Rural. Econ. 2018, 2, 300–305. [Google Scholar]

- Klimek, D. Sustainable Enterprise Capital Management. Economies 2020, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marshall, A. Economics of Industry; Macmillan & Co.: London, UK, 1892. [Google Scholar]

- Arrow, K.J.; Debreu, G. Existence of an equilibrium for a competitive economy. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1954, 22, 265–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, B. A resource-based view of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, B. The use of resources in resource acquisition. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1369–1373. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, F.M.; McGowan, J.I. On the misuse of accounting rates of return to infer monopoly profits. Am. Econ. Rev. 1983, 73, 82–97. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, R.G. The performance evaluation manifesto. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1991, 69, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Crowther, D. Dimensions of corporate performance: Towards a new evaluation paradigm. In Proceedings of the Second Research Colloquium; Henley: Henley-Nisbet; James Nisbet & Co. Ltd.: London, UK, 1995; pp. 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Crowther, D. Corporate performance operates in three dimensions. Manag. Audit. J. 1996, 11, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šalaga, J.; Bartosova, V.; Kicova, E. Economic Value Added as a Measurement Tool of Financial Performance. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 26, 484–489. [Google Scholar]

- Shalini, H.S.; Preethi, V.S. A Comparative Study of Financial Dialectics and Economic Value Added vs. Traditional Profit based Measures: A case study at BHEL-Electro Porcelains Division (EPD). J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 6, 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Itang’ata, M.J. Discussion Paper an Assessment of the Criticisms of the Principle of Profit Maximization. J. Interdiscip. Econ. 2010, 23, 85–107. [Google Scholar]

- Keen, S.; Stanish, R.K. Profit Maximization, Industry Structure, and Competition: A critique of neoclassical theory. Physica A 2006, 370, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lambert, C.; Sponem, S. Corporate governance and profit manipulation: A French field study. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2005, 16, 717–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Evgenidis, A.; Tsagkanos, A. Asymmetric effects on the international transmission of US financial stress. A Threshold VAR approach. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2017, 51, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsagkanos, A.; Siriopoulos, C.; Vartholomatou, K. FDI and Stock Market Development: Evidence from a ‘new’ emerging market. J. Econ. Stud. 2019, 46, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| The Share Capital | (In Thous.) PLN | % |

|---|---|---|

| fixed assets | 9426 | 14.49 |

| financial | 34,925 | 53.70 |

| structural | 2211 | 3.40 |

| human | 9511 | 14.63 |

| market | 1432 | 2.20 |

| social | 7534 | 11.58 |

| Total | 65,039 | 100.00 |

| Corporate Capitals | Symbol | Current Capital Value | Symbol | Optimal Capital Value | Formula | Difference | Formula | Difference Percentage | Formula | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fixed assets | k01 = | 9,426,000 | kd1 = | 10,450,000 | |k01–kd1| = | 1,024,000 | |k01–kd1|/k01 = | 11% | k01/K = | 0.14493 |

| financial | k02 = | 34,925,000 | kd2 = | 28,543,000 | |k02–kd2| = | 6,382,000 | |k02–kd2|/k02 = | 18% | k02/K = | 0.53699 |

| structural | k03 = | 2,211,000 | kd3 = | 2,469,000 | |k03–kd3| = | 258,000 | |k03–kd3|/k03 = | 12% | k03/K = | 0.03399 |

| human | k04 = | 9,511,000 | kd4 = | 9,770,000 | |k04–kd4| = | 259,000 | |k04–kd4|/k04 = | 3% | k04/K = | 0.14624 |

| market | k05 = | 1,432,000 | kd5 = | 1,945,000 | |k05–kd5| = | 513,000 | |k05–kd5|/k05 = | 36% | k05/K = | 0.02202 |

| social | k06 = | 7,534,000 | kd6 = | 10,967,000 | |k06–kd6| = | 3,433,000 | |k06–kd6|/k06 = | 46% | k06/K = | 0.11584 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Klimek, D.; Jędrych, E. A Model for the Sustainable Management of Enterprise Capital. Sustainability 2021, 13, 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010183

Klimek D, Jędrych E. A Model for the Sustainable Management of Enterprise Capital. Sustainability. 2021; 13(1):183. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010183

Chicago/Turabian StyleKlimek, Dariusz, and Elżbieta Jędrych. 2021. "A Model for the Sustainable Management of Enterprise Capital" Sustainability 13, no. 1: 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010183

APA StyleKlimek, D., & Jędrych, E. (2021). A Model for the Sustainable Management of Enterprise Capital. Sustainability, 13(1), 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010183