Purchasing Behavior of Organic Food among Chinese University Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

3. Materials and Methods

4. Preliminary Survey

4.1. Measures

4.2. Results

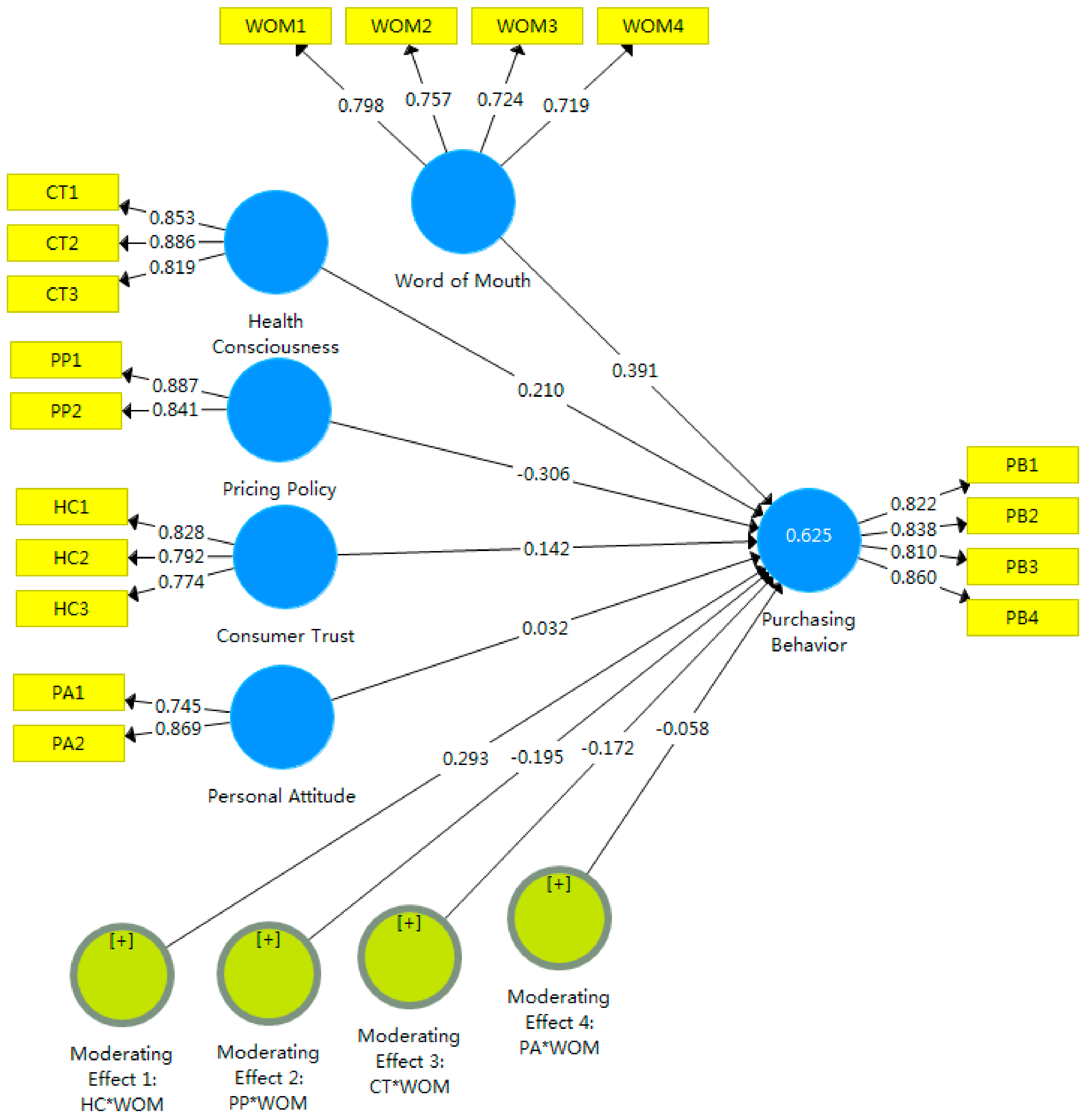

4.3. Assessment of Measurement Model

4.4. Results of the Structural Model

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Items |

|---|---|

| Health Consciousness | HC1 I choose food carefully to ensure good health. HC2 I consider myself a health-conscious consumer. HC3 I often think about health-related issues. |

| Personal Attitude | PA1 Consuming organic food is good. PA2 Consuming organic food is pleasant |

| Consumer Trust | CT1 The traceability system provides objective information on agro-products sufficiently. CT2 Information provided by the traceability system is trustworthy, CT3 I expect the traceability system to provide accurate information trustfully |

| Pricing Policy | PP1I get good value for my money. PP2 The relationship between the price and quality is good. |

| Word of Mouth | WOM1 My family/friends positively influence my attitude towards a specific organic food brand. WOM2 My family/friends mention positive things I had not considered about a specific organic food brand. * WOM3 My family/friends provide me with positive ideas about a specific organic food brand. WOM4 My family/friends positively influence my evaluation of a specific organic food brand. WOM5 My family/friends help me make the decision in selecting a specific organic food brand. |

| Purchasing Behavior | PB1 I often buy organic food products. PB2 I always try to buy organic food with green labeling marks PB3 I buy organic food products even if they have a higher price, PB4 I recommend organic food products to my relatives and friends |

References

- Du, S.; Bartels, J.; Reinders, M.; Sen, S. Organic consumption behavior: A social identification perspective. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 62, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, P.; Tarafder, T.; Pearson, D.; Henryks, J. Intention-behaviour gap and perceived behavioral control-behavior gap in theory of planned behavior: Moderating roles of communication, satisfaction, and trust in organic food consumption. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 81, 103838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willer, H.; Schlatter, B.; Trávníček, J.; Kemper, L.; Lernoud, J. The World of Organic Agriculture: Statistics and Emerging Trends 2020. Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL) and IFOAM—Organics International. 2020. Available online: https://www.fibl.org/fileadmin/documents/shop/5011-organic-world-2020.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2021).

- Lazzarini, G.A.; Visschers, V.H.M.; Siegrist, M. How to improve consumers ‘ environmental sustainability judgments of foods. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachero-Martínez, S. Consumer Behaviour towards Organic Products: The Moderating Role of Environmental Concern. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassen, T.; El Bilali, H.; Allahyari, M.S. Impact of COVID-19 on Food Behavior and Consumption in Qatar. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempel, C.; Hamm, U. Local and/or organic: A study on consumer preferences for organic food and food from different origins. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwah, S.; Dhir, A.; Sagar, M.; Gupta, B. Determinants of organic food consumption. A systematic literature review on motives and barriers. Appetite 2019, 143, 104402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, A.; Dhir, A.; Kaur, P.; Kushwah, S.; Salo, J. Behavioral reasoning perspectives on organic food purchase. Appetite 2020, 154, 104786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, G.; Borrello, M.; Guccione, G.D.; Schifani, G.; Cembalo, L. Organic food consumption: The relevance of the health attribute. Sustainability 2020, 12, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwah, S.; Dhir, A.; Sagar, M. Understanding consumer resistance to the consumption of organic food. A study of ethical consumption, purchasing, and choice behavior. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 77, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Nguyen, H.V.; Chou, T.P.; Chen, C.P. A comprehensive model of consumers’ perceptions, attitudes and behavioral intention toward organic tea: Evidence from an emerging economy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basha, M.B.; Lal, D. Indian consumers’ attitudes towards purchasing organically produced foods: An empirical study Indian consumers ’ attitudes towards purchasing organically produced foods: An empirical study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 215, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Xuhui, W.; Nasiri, A.; Ayyub, S. Determinant Factors Influencing Organic Food Purchase Intention and the Moderating Role of Awareness: A Comparative Analysis. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 63, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organic Food Domestic Sales Value in China from 2011 to 2019. 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/448044/organic-food-sales-in-china/ (accessed on 11 February 2021).

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Factors Affecting Green Purchase Behaviour and Future Research Directions. Int. Strat. Manag. Rev. 2015, 3, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.S.; Tsai, B.K. Consumer response to retail performance of organic food retailers. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, O.; Chen, X.; Au, R. Consumer behavior of pre-teen and teenage youth in China. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2013, 4, 247–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinillo, S.; Vidal-Branco, M.; Japutra, A. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services Understanding the drivers of organic foods purchasing of millennials: Evidence from Brazil and Spain. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.; Ingerslev, M.; Eriksen, M.R. How the interplay between consumer motivations and values influences organic food identity and behavior. Food Policy 2018, 74, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.H.; Nguyen, T.N.; Thu, T.; Phan, H.; Thanh, N. Evaluating the purchase behavior of organic food by young consumers in an emerging market economy. J. Strateg. Mark. 2018, 4488, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Fleșeriu, C.; Cosma, S.A.; Bocăneț, V. Values and Planned Behaviour of the Romanian Organic Food Consumer. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekima, B.; Oswald, A.I.; Wafa, S.A.; Chekima, K. Narrowing the gap: Factors driving organic food consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 1438–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsi, H.R.; Najafabadi, M.O.; Jamal, S.; Hosseini, F. Designing a three-phase pattern of organic product consumption behavior. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 79, 103743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Verma, P. Factors influencing Indian consumers’ actual buying behavior towards organic food products. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 167, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M. Determinants of organic food purchases: Evidence from household panel data. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 68, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, G.; Pathak, P. Intention to buy eco-friendly packaged products among young consumers of India: A study on developing nation. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 141, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Intention to purchase organic food among young consumers: Evidence from a developing nation. Appetite 2016, 96, 122–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Fu, C.J.; Chen, Y.Y. Trust factors for organic foods: Consumer buying behavior. Br. Food J. 2019, 122, 414–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, D.; Memery, J.; De Silva, M. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services The mindful consumer: Balancing egoistic and altruistic motivations to purchase local food. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 40, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareklas, I.; Carlson, J.R.; Muehling, D.D.; Carlson, J.R.; Muehling, D.D. “I Eat Organic for My Benefit and Yours”: Egoistic and Altruistic Considerations for Purchasing Organic Food and Their Implications for Advertising Strategists “I Eat Organic for My Benefit and Yours”: Egoistic and Altruistic Considerations for Purcha. J. Advert. 2014, 43, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feil, A.A.; da Silva Cyrne, C.C.; Sindelar, F.C.W.; Barden, J.E.; Dalmoro, M. Profiles of sustainable food consumption: Consumer behavior toward organic food in southern region of Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghali, Z. Motives of Willingness to Buy Organic Food under the Moderating Role of Consumer Awareness. J. Sci. Res. Reps. 2020, 25, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittersø, G.; Tangeland, T. The role of consumers in transitions towards sustainable food consumption.The case of organic food in Norway. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 92, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, A.; Wang, C.; Tanveer, Y. Organic food consumerism through social commerce in China. J. Mark. Logist. 2019, 31, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacho, F. What influences consumers to purchase organic food in developing countries? Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 3695–3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, M.; Cass, A.O.; Otahal, P.; Massey, M. A meta-analytic study of the factors driving the purchase of organic food. Appetite 2018, 125, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, J.; Paul, J. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services Consumer behavior and purchase intention for organic food: A review and research agenda. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 38, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A. For young consumers, farm-to-fork is not organic: A cluster analysis of university students. HortScience 2020, 55, 1475–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moliner-Velázquez, B.; Ruiz-Molina, M.-E.; Fayos-Gardó, T. Satisfaction with service recovery: Moderating effect of age in word-of-mouth. J. Consum. Mark. 2015, 32, 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Ahmed, W.; Muhammad, R.; Jafar, S.; Rabnawaz, A.; Jianzhou, Y. Computers in Human Behavior eWOM source credibility, perceived risk and food product customer’s information adoption. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 66, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, A. Influence of Electronic Word of Mouth on Purchase Intention of Fashion Products on Social Networking Websites. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2017, 11, 597–622. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelidou, N.; Hassan, L.M. The role of health consciousness, food safety concern, and ethical identity on attitudes and intentions towards organic food. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Smith, S. Understanding Local Food Consumers: Theory of Planned Behavior and Segmentation Approach Understanding Local Food Consumers: Theory of Planned Behavior and Segmentation Approach. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2018, 24, 196–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanpanah, M.; Forouzani, M. Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour to predict Iranian students’ intention to purchase organic food. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Lam, T.; Hsu, C.H. Negative Word-of-Mouth Communication Intention: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2006, 30, 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küster-Boluda, I.; Vila, N. Can Health Perceptions, Credibility, and Physical Appearance of Low-Fat Foods Stimulate Buying Intentions? Foods 2020, 9, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, R.; Singh, D. An analysis of factors affecting growth of organic food. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 2308–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiziana de Magistris, A.G. The decision to buy organic food products in Southern Italy. Br. Food J. 2011, 110, 929–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagata, L. Consumers’ beliefs and behavioral intentions towards organic food.Evidence from the Czech. Republic. Appetite 2012, 59, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzaoui Essoussi, L.; Linton, J.D. New or recycled products: How much are consumers willing to pay? J. Consum. Mark. 2010, 27, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Pacho, F.; Liu, J.; Kajungiro, R. Factors influencing organic food purchase intention in Tanzania and Kenya and the moderating role of knowledge. Sustainability 2019, 11, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryła, P. Organic food consumption in Poland: Motives and barriers. Appetite 2016, 105, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mkhize, S.; Ellis, D. Creativity in a marketing communication to overcome barriers to organic produce purchases: The case of a developing nation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lobo, A.; Rajendran, N. Drivers of organic food purchase intentions in mainland China—Evaluating potential customers’ attitudes, demographics and segmentation. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henryks, J.; Cooksey, R.; Wright, V.; Cooksey, R.A.Y.; Wright, V.I.C. Organic Food at the Point of Purchase: Understanding Inconsistency in Consumer Choice. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2014, 20, 452–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Datta, B.; Barai, P. Modeling and Promoting Organic Food Purchase Modeling and Promoting Organic Food Purchase. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2016, 22, 632–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Toni, D.; Eberle, L.; Larentis, F.; Milan, G.S. Antecedents of Perceived Value and Repurchase Intention of Organic Food Antecedents of Perceived Value and Repurchase Intention of Organic Food. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2017, 24, 456–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekmahmud, M.; Fekete-Farkas, M. Why not green marketing? Determinates of consumers’ intention to green purchase decision in a new developing nation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; Li, J.; Yong, S.; Suryadi, K.; Lim, W.M.; Suryadi, K. Consumers’ Perceived Value and Willingness to Purchase Organic Food Consumers’ Perceived Value and Willingness to Purchase Organic Food. J. Glob. Mark. 2014, 27, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sana, S.S. Price competition between green and nongreen products under corporate social responsible firm. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102118. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0969698920301788 (accessed on 10 May 2021). [CrossRef]

- Suh, B.W.; Eves, A.; Lumbers, M. Developing a Model of Organic Food Choice Behavior. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2015, 43, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loo, E.J.; Nguyen, M.; Diem, H.; Pieniak, Z.; Verbeke, W. Consumer attitudes, knowledge, and consumption of organic yogurt. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 2118–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rödiger, M.; Hamm, U. How are organic food prices affecting consumer behavior? A review. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 43, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Sarti, S.; Frey, M. Are green consumers really green? Exploring the factors behind the actual consumption of organic food products. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2019, 28, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhanifard, Y. Hybrid modeling of the consumption of organic foods in Iran using exploratory factor analysis and an artificial neural network. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.T.; Nguyen, L.H.A.; Tran, T.T. Purchase Behavior of Young Consumers Toward Green Packaged Products in Vietnam. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 985–996. [Google Scholar]

- Petrescu, D.C.; Petrescu-mag, R.M. Organic Food Perception: Fad, or Healthy and Environmentally. Sustainability 2015, 7, 12017–12031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Decisional factors driving organic food consumption Generation of consumer purchase intentions. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 1066–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernqvist, F.; Ekelund, L. Credence and the effect on consumer liking of food—A review. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 32, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jing, L.; Bai, Q.; Shao, W.; Feng, Y.; Yin, S.; Zhang, M. Application of an integrated framework to examine Chinese consumers’ purchase intention toward genetically modified food. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 65, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttavuthisit, K.; Thøgersen, J. The Importance of Consumer Trust for the Emergence of a Market for Green Products: The Case of Organic Food. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 140, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, V.; Cavallo, C.; Caso, D.; Del Giudice, T.; De Devitiis, B.; Viscecchia, R.; Nardone, G.; Cicia, G. Explaining consumer purchase behavior for organic milk: Including trust and green self-identity within the theory of planned behavior. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 76, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleenbecker, R.; Hamm, U. Consumers ‘ perception of organic product characteristics. A review. Appetite 2013, 71, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Gao, Z.; Zeng, Y. Willingness to pay for the “Green Food” in China. Food Policy 2014, 45, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.M.; Ann, E.F. Reducing the intention-to-behavior gap for locally produced foods purchasing: The role of store, trust, and price. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2016, 44, 508–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persaud, A.; Schillo, S. Purchasing organic products: Role of social context and consumer innovativeness. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2017, 35, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.A.; Joarder MH, R.; Ratan, S.R.A. Consumers’ anti-consumption behavior toward organic food purchase: An analysis using SEM. Br. Food J. 2018, 121, 104–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, M.; Pap, A.; Stanic, M. What drives organic food purchasing?—Evidence from Croatia. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 734–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Hwang, J. The driving role of consumers’ perceived credence attributes in organic food purchase decisions: A comparison of two groups of consumers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 54, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalco, A.; Noventa, S.; Sartori, R.; Ceschi, A. Predicting organic food consumption: A meta-analytic structural equation model based on the theory of planned behavior. Appetite 2017, 112, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.F.Y.; To, W.M. An extended model of value-attitude-behavior to explain Chinese consumers’ green purchase behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attitudes and the prediction of behavior. Consumer attitudes and behavior. In Handbook of Consumer Psychology, 1st ed.; Haugvedt, C.P., Herr, P.M., Cardes, F.R., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2008; pp. 525–548. [Google Scholar]

- Koklic, M.K.; Golob, U.; Podnar, K.; Zabkar, V. The interplay of past consumption, attitudes and personal norms in organic food buying. Appetite 2019, 137, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, S.; Khare, A. The Role of Retailer Trust and Word of Mouth in Buying Organic Foods in an Emerging Market. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2017, 23, 926–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwandee, S.; Surachartkumtonkun, J.; Lertwannawit, A. EWOM fi restorm: Young consumers and online community. Young Consum. 2020, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, S.; Ghani, M.; Mahmood, A.; Ali, J. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services Refining e-shoppers’ perceived risks: Development and validation of new measurement scale. J. Retail. Consum Serv. 2021, 58, 102285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.C.; Prayag, G.; Fieger, P.; Dyason, D. Beyond panic buying: Consumption displacement and COVID-19. J. Serv. Manag. 2021, 32, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le-Hoang, P.V. The effects of Electronic Word of Mouth (eWOM) on the adoption of consumer eWOM information. Indep. J. Manag. Prod. 2020, 11, 1760–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudreault, A.R. Natural: Influences of Students’ Organic Food Perceptions Natural: Influences of Students’ Organic. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2009, 15, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodorfos, G.N.; Dennis, J. Journal of Food Products Consumers’ Intent: In the Organic Food Market. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2008, 14, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, A.; Gahfoor, R.Z. Satisfaction and revisit intentions at fast-food restaurants. Future Bus. J. 2020, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curina, I.; Francioni, B.; Hegner, S.M.; Cioppi, M. Brand hate and non-repurchase intention: A service context perspective in a cross-channel setting. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 102031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.G.; Lafreniere, K.C. How online word-of-mouth impacts receivers. Consum. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 3, 34–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See-to, E.W.K.; Ho, K.K.W. Computers in Human Behavior Value co-creation and purchase intention in social network sites: The role of electronic Word-of-Mouth and trust—A theoretical analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadas, K.; Avlonitis, G.J.; Carrigan, M. Green marketing orientation: Conceptualization, scale development, and validation. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 80, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudel, R. Sustainable consumer behavior. Consum. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 2, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Qiao, L.; Hu, T. eWOM in Mobile Social Media: A study about Chinese Wechat use. Symp. Serv. Innov. Big Data Area 2017, 714263, 176–200. [Google Scholar]

- Chaney, D.; Touzani, M.; Ben Slimane, K. Marketing to the (new) generations: Summary and perspectives. J. Strateg. Mark. 2017, 25, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, O.; Flores-Zamora, J.; Khelladi, I.; Ivanaj, S.; Ivanova, O.; Flores-Zamora, J. The generational cohort effect in the context of responsible consumption cohort effect. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 1162–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, D.B.; Powers, T.L.; Valentine, D.B.; Southwestern, G.; Powers, T.L. Generation Y values and lifestyle segments. J. Consum. Mark. 2013, 30, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Bock, D.; Joseph, M.; Lu, L.; Bock, D.; Joseph, M. Green marketing: What the Millennials buy. J. Bus. Strat. 2013, 34, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.-C.; Huang, Y.-H. The influence factors on choice behavior regarding green products based on the theory of consumption values. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 22, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselmsson, J.; Burt, S.; Tunca, B. An integrated retailer image and brand equity framework: Re-examining, extending, and restructuring retailer brand equity. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 38, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, Y.C.; Park, J.; Chung, M. Effect of the food traceability system for building trust: Price premium and buying behavior. Inf. Syst. Front. 2009, 11, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cham, T.H.; Lim, Y.M.; Aik, N.C.; Tay, A.G.M. Antecedents of hospital brand image and the relationships with medical tourists’ behavioral intention. J. Pharm. Healthc. Mark. 2016, 10, 412–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Lockwood, C.M.; Hoffman, J.M.; West, S.G.; Sheets, V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.; Hollingsworth, C.L.; Randolph, A.B.; Yee, A.; Chong, L.; Hair, J. An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common Method Bias in PLS-SEM. Int. J. e-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Ismagilova, E.; Hughes, D.L.; Carlson, J.; Filieri, R.; Jacobson, J.; Jain, V.; Karjaluoto, H.; Kefi, H.; Krishen, A.S.; et al. Setting the future of digital and social media marketing research: Perspectives and research propositions. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 102168, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, A.; Ali, S.; Ahmad, M.A.; Akbar, M.; Danish, M. Understanding the antecedents of organic food consumption in Pakistan: Moderating role of food neophobia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le-Anh, T.; Nguyen-To, T. Consumer purchasing behavior of organic food in an emerging market. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 141 | 42 |

| Female | 194 | 58 |

| Income (Yuan) | ||

| Less than 2000 | 44 | 13 |

| 2001–4000 | 97 | 29 |

| 4001–6000 | 137 | 41 |

| More than 6000 | 57 | 17 |

| Organic Food Products | ||

| Fruits and Vegetables | 94 | 28 |

| Organic Dairy products and drinks | 128 | 38.2 |

| Snacks andNuts | 91 | 27.2 |

| Rice, Grain, Meat | 17 | 5.1 |

| Others (please specify) | 5 | 1.5 |

| Purchasing Frequency | ||

| Usually | 104 | 31 |

| Occasionally | 171 | 51 |

| Seldom | 60 | 18 |

| Construct | Items | FL | CA | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC | HC1 | 0.853 | 0.894 | 0.903 | 0.83 |

| HC2 | 0.886 | ||||

| HC3 | 0.819 | ||||

| PA | PA1 | 0.745 | 0.857 | 0.879 | 0.787 |

| PA2 | 0.869 | ||||

| CT | CT1 | 0.828 | 0.814 | 0.825 | 0.861 |

| CT2 | 0.792 | ||||

| CT3 | 0.774 | ||||

| PP | PP1 | 0.887 | 0.857 | 0.8 | 0.811 |

| PP2 | 0.841 | ||||

| WOM | WOM1 | 0.798 | 0.863 | 0.879 | 0.82 |

| WOM2 | 0.757 | ||||

| WOM3 | 0.724 | ||||

| WOM4 | 0.719 | ||||

| PB | PB1 | 0.822 | 0.886 | 0.897 | 0.872 |

| PB2 | 0.838 | ||||

| PB3 | 0.81 | ||||

| PB4 | 0.86 |

| HC | T | PA | PP | WOM | PB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC | 0.830 | |||||

| PP | 0.476 | 0.861 | ||||

| CT | 0.368 | 0.531 | 0.787 | |||

| PA | 0.418 | 0.511 | 0.472 | 0.811 | ||

| WOM | 0.381 | 0.241 | 0.339 | 0.446 | 0.820 | |

| PB | 0.519 | 0.463 | 0.453 | 0.536 | 0.591 | 0.872 |

| HC | PA | T | PP | WOM | PB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC | - | 2.105 | 1.658 | 1.751 | 1.296 | 1.863 |

| PA | 1.838 | - | 1.933 | 1.692 | 1.619 | 1.712 |

| T | 1.932 | 1.397 | - | 1.719 | 1.821 | 2.116 |

| PP | 1.695 | 1.681 | 1.837 | - | 1.784 | 1.673 |

| WOM | 1.158 | 1.694 | 1.597 | 1.775 | - | 1.699 |

| PB | 1.631 | 1.397 | 1.592 | 1.801 | 1.499 | - |

| No. | Path Relationship | Estimate | t-Statistics | p Value | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HC → PB | 0.210 | 2.152 | 0.032 | Supported |

| 2 | PP → PB | −0.306 | 2.519 | 0.012 | Supported |

| 3 | CT → PB | 0.142 | 1.142 | 0.254 | Not Supported |

| 4 | PA → PB | 0.032 | 0.266 | 0.790 | Not Supported |

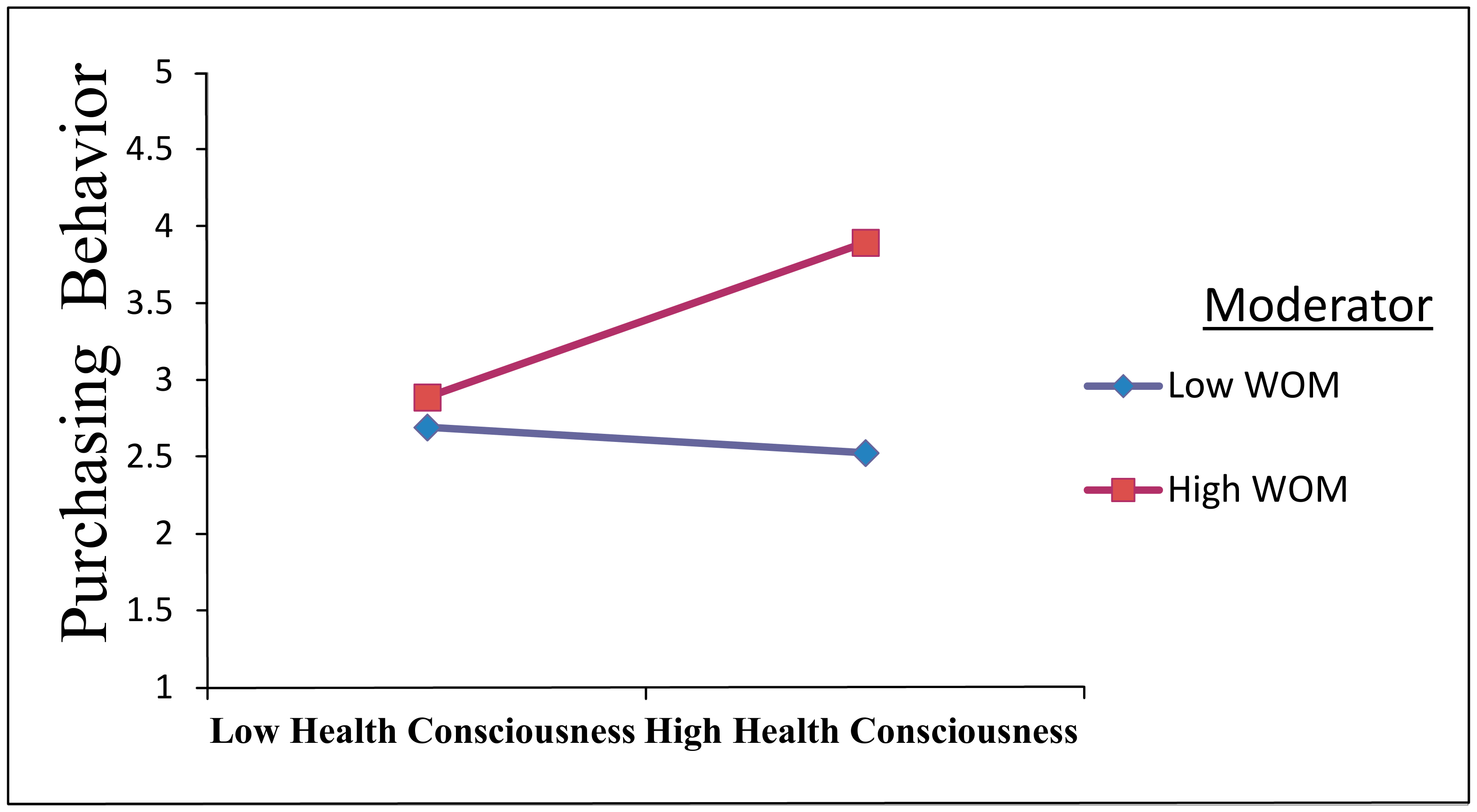

| 5a | HC * WOM → PB | 0.293 | 2.204 | 0.028 | Supported |

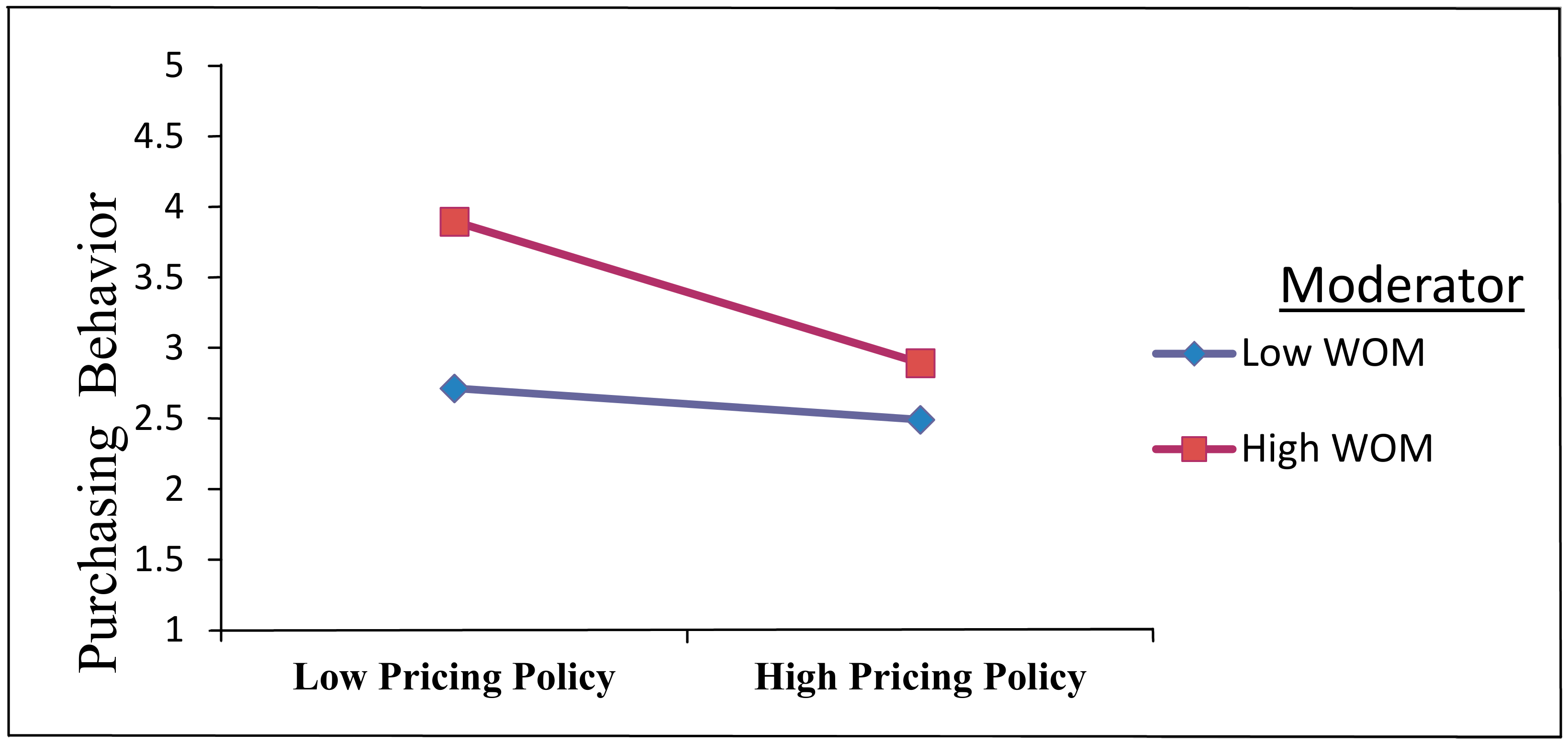

| 5b | PP * WOM → PB | −0.195 | 2.234 | 0.026 | Supported |

| 5c | CT * WOM → PB | −0.172 | 1.715 | 0.087 | Not Supported |

| 5d | PA * WOM → PB | −0.058 | 0.498 | 0.618 | Not Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ali, H.; Li, M.; Hao, Y. Purchasing Behavior of Organic Food among Chinese University Students. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5464. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105464

Ali H, Li M, Hao Y. Purchasing Behavior of Organic Food among Chinese University Students. Sustainability. 2021; 13(10):5464. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105464

Chicago/Turabian StyleAli, Hazem, Min Li, and Yunhong Hao. 2021. "Purchasing Behavior of Organic Food among Chinese University Students" Sustainability 13, no. 10: 5464. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105464

APA StyleAli, H., Li, M., & Hao, Y. (2021). Purchasing Behavior of Organic Food among Chinese University Students. Sustainability, 13(10), 5464. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105464