Abstract

Consumers are increasingly concerned about food quality. The “Same line Same standard Same quality” (Santong) program has been implemented to improve food quality in the Chinese domestic market. The Santong program means that exporters are encouraged to produce goods on the same production line, following the same standards and the same quality requirements for both the export target market and the domestic market. Using data collected from an online choice experiment on tomatoes, we examine Chinese consumer preferences and their willingness to pay (WTP) for the Santong claim, export target market quality and organic certification. Three types of export target market, indicating different technical regulations and standards, are considered. Our results show that consumers are willing to pay for the Santong quality claim and for export goods with a target market of “EU”. Furthermore, we also identify the substitution effects between the Santong claim and organic certification. The results of our study provide solutions for both Chinese exporters and the Chinese government to meet the need for a high level of food quality accompanied by domestic consumption upgrade, and achieve the transformation from export to domestic sales. Our results may also provide solutions for other emerging economies, where governments raise the level of food quality in domestic markets and support the domestic sales of exporters after the shock of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in 2019.

1. Introduction

Food quality and safety have become a rising matter for concern all over the world, especially in emerging economies [1]. The respective governments usually establish laws, regulations, and standards to control food safety. However, many serious food safety scandals have occurred in recent years, which have seriously undermined the Chinese consumers’ faith in the domestic food industry [2]. Chinese consumer demand for safe and high-quality food (e.g., imported food and organic food) is increasing [3,4]. As a response, in 2016, the Chinese government implemented the “Same line Same standard Same quality” (Santong) program to improve the food quality in the domestic market. Furthermore, the impact of the coronavirus pandemic in 2019 (COVID-19) has sent the world economy into a severe recession and has caused a contraction in international trade. China’s 2020 Government Work Report proposed to support the domestic sale of export products. The State Council of China subsequently issued a circular taking measures to help exporters sell products in the domestic market, which encouraged enterprises to develop “Same line Same standard Same quality” (Santong) products (“China to support exporters explore the domestic market”, http://english.www.gov.cn/policies/latestreleases/202006/22/content_WS5ef0a5abc6d0a6946639c89f.html, accessed on 18 May 2021).

For many years, the variations in standards requirements between domestic products and export products led to certain quality differences, and these differences led to a consumer “trust gap”. In the Santong program, exporters are encouraged to produce products on the same production line following the same standards and the same quality requirements for both the export target market and the domestic market. The “same standard” means that the quality and safety management systems of each enterprise conform to the technical regulations and standards of the import countries (regions). It is also worth noting that the product standards should be in accordance with Chinese standards if they are stricter (Chinese Industry Standard RB/T 157-2017: Same line Same standard Same quality—Implementation guidelines for export food enterprises, https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=SCHF&dbname=SCHF&filename=schf201909376, accessed on 18 May 2021). In China, there are nearly 20,000 food export enterprises, and food products are exported to more than 180 countries and regions. For many years, over 99.9% of China’s exported foodstuffs have been up to standard (Certification and Accreditation Administration of the People’s Republic of China “Same line Same standard Same quality” public information platform was launched in Beijing, http://www.cnca.gov.cn/rdzt/2016/txtbtz/hdbd/201605/t20160510_51130.shtml, accessed on 18 May 2021). By the end of 2017, there were 13,452 food export enterprises, 2775 Santong food enterprises and more than 10,000 Santong food products in China (2018 Yearbook of Certification and Accreditation of China, https://oversea.cnki.net/KNavi/YearbookDetail?pcode=CYFD&pykm=YZGRZ&bh=, accessed on 18 May 2021). However, little is known about how consumers perceive Santong food products, and the effectiveness of the Santong claim has not yet been evaluated.

Since Santong food products are required to conform to the corresponding standards of export target markets, the export target market may be used as an important signal to infer the required quality of Santong food products by consumers. For example, as the third-largest agricultural export market of mainland China, Hong Kong has higher standards in pesticide residue than does mainland China. The European Union is another important agricultural export market for China. The European food safety management system is one of the most developed systems worldwide. Taking maximum residue limits (MRLs) for tomatoes as an example, the number of regulated pesticides of MRLs is 114 in the EU, 67 in Hong Kong and only 12 in mainland China [5]. A considerable amount of literature has explored the effects of the region of origin (country of origin) in food markets [6,7,8,9]. Region of origin means that the products are produced in a region and conform to the quality standard requirements of that region. Similarly, products exported to developed countries meet strict standards because it is “a must” for enterprises that wish to enter the target market, while products sold in the domestic market are not so strict in their mandatory regulations and standards [10]. That is, products can be exported to the target market which should have stricter standards applied and use more advanced management tools. In contrast, Santong means that the products are produced domestically but conform to the quality standards requirements of the export target market, which makes investigating the export target market helpful.

Due to the frequent occurrence of food safety scares, Chinese consumers are increasingly concerned about food quality and safety [11,12]. The Santong program is not the only solution addressing such concerns. With their strict food production standards, the organic food market has been growing rapidly in China [13]. Previous studies have found that consumers are willing to pay higher prices for organic food [14,15]. In the domestic market, some Santong food products are also labeled with organic certification to meet the consumer demand for safer food, but there is no existing study examining the influence of the combination of the Santong claim and organic certification. Given that both the organic certification and the Santong claim provide useful information about the products, consumers can use both labels to assess food quality. If this is the case, the question of whether they are substitutes or complements arises. On the one hand, consumers may believe that the Santong claim already signals high quality so that the additional information carried by organic certification may be perceived as substitutable, therefore offsetting the value of the Santong claim. On the other hand, organic certification reinforces the implication of food quality, thereby increasing the consumers’ confidence in Santong food products. It is necessary to examine the interactions between these two attributes in order to offer more preference information to exporters.

The main purpose of this study is to assess the effectiveness of the Santong program in improving the perception of food quality domestically. Focusing on tomatoes, we conducted a choice experiment to analyze Chinese consumer preferences for the Santong claim, the export target market and organic certification. First, we examined consumer preferences and their willingness to pay (WTP) for Santong items. As Santong food products with different export target markets usually conform to different standards of quality requirements, we explored Chinese consumer preferences for different export target markets, and the interaction between the Santong claim and the export target market. Second, we compared consumer preferences and WTP for the Santong claim and organic certification, as well as analyzing whether Santong and organic attributes are complementary or substitutable.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we briefly review the background and literature. In Section 3, we present the research methods, including choice experiment design, data collection and econometric models. In Section 4, we describe the characteristics of the sample and report the empirical results. In Section 5, we discuss the findings. The paper closes with managerial implications and limitations in the final Section 6.

2. Background and Literature Review

Consumers usually have less information about food quality than producers when making purchase decisions. In order to avoid the negative effects of asymmetric information, enterprises can communicate quality signals to consumers through self-declared claims or certifications [3,16,17,18]. Self-declared claims are voluntary, public commitments made by enterprises [19]. Short statements, symbols or graphics can be used to indicate the relevant claims of the products [20]. For the Santong claim in our study, in addition to the self-declaration of production in accordance with “Same line Same standard Same quality”, export registration and actual export performances, as well as hazard analysis critical control point (HACCP) or good agricultural practices (GAP) certification are also required. The Santong program adopts the “export enterprise filing + self-declared claim + the third-party certification” pattern and integrates the commerce trading platform and public information platform (Santong public information platform, http://www.santonghui.org.cn/txtbtz/front, accessed on 18 May 2021) to ensure that the products are produced on the same production line, following the same standards and the same quality requirements for both foreign and domestic markets. As a solution to address food quality concerns, however, the impact of the Santong claim on consumer preferences has not been studied in previous literature.

As Santong food products are required to conform to the corresponding quality standards of their export target markets, we expect that there are some similarities between the effect of the export target market and the region-of-origin (ROO) or country-of-origin (COO) effect. The impacts of ROO or COO on consumer preferences have been explored extensively [21,22,23,24,25]. ROO is an important quality cue, including information on product reliability and safety, which can reduce consumers’ purchase risks [26,27]. Numerous researchers have found that consumers are willing to pay a higher price premium for products sourced from more economically developed regions than for those from less economically developed regions [4,28,29]. For example, Yin et al. [30] show that Chinese consumers prefer products from the European Union. However, in certain cases, consumers may prefer food products from their own country or region [31,32], which is related to consumer ethnocentrism [24]. Both Santong and ROO products are obligated to meet the food quality standards requirements of specific regions. The difference is that Santong products are produced and sold domestically. Therefore, whether the effects of Santong and ROO lead to consumers’ different food quality perceptions or not, there is no existing literature investigating the influence of Santong on consumer preferences.

Abundant studies have investigated consumer preferences for organic labels [33,34,35], finding that consumers generally believe that organic food is safer, healthier, and more environmentally friendly [36,37], and they are willing to pay a price premium for organic food [15,30,38,39,40]. Certain studies compare consumer preferences and their willingness to pay for products with different organic certifications [14,41]. Chinese consumers are willing to pay more for various organic labels, especially those from developed countries or regions [42,43]. Other studies examine the interaction effects between organic certifications and other quality cues, such as origin, brands, and traceability information. Xie et al. [31] examined US consumer preferences for imported organic foods and found that the USDA organic label may mitigate the negative effects of products from China. There are substitution effects between organic certifications and local production claims, and traceability information [28,44], as well as complementary effects between organic certifications and brands [3,13].

Several methods are available to analyze consumer preferences, including the study of revealed preferences via scanner data, and stated preferences through choice experiments or experiment auctions [45]. The choice experiment is one of the methods most frequently used to examine consumer preferences for “complex goods” [46], especially food products which comprise several attributes. The theoretical system of a choice experiment is similar to that of the contingent valuation method. The choice experiment allows us to make a trade-off between two products in an experimental context that is similar to a realistic market scenario [47]. Thus, the willingness to pay would be detected indirectly and implicitly rather than directly through open questions.

In summary, consumer preferences for quality cues (such as claims, origin, and organic certification) have been studied extensively; as a new solution to improve food quality, little is known about consumer preferences for Santong products. Our study makes two contributions to the literature. First, as a solution to improve food quality, the Santong label may be a quality cue for consumer choice, but Santong food products with different export target markets conform to different quality standards requirements. Thus, we provide insights into consumer preferences for the Santong claim and export target market, and fill the gap in the literature by assessing consumer preferences and WTP for different export target markets. Second, we compare Chinese consumer preferences and their willingness to pay for the Santong claim and organic certification and examine the interactions between these two attributes.

3. Methods

3.1. Attribute Specifications

We focused our study on tomatoes, because they are one of the most popular fresh vegetables in China that consumers purchase on a regular basis. China is the largest tomato producer in the world, and the tomato is an advantageous variety of exported vegetables. Furthermore, tomato producers in China are generally small, with dispersed production and few well-known brands. This may reduce the impact of brands on consumer choices [13]. Four tomato attributes are considered in our choice experiment, including price, quality claim, export target market, and organic status. All attributes and the specific levels are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Attributes and levels in the choice experiment.

Price is considered at four levels, based on the market price for various tomato types, including conventional and organic tomatoes from different places of purchase (farmers’ market, supermarket, local grocery stores, and online shops) at the time of the study in April 2020 (the average market price was about 10 RMB/500 g). As a result, the price levels chosen for our choice experiment are 5, 10, 15, and 20 RMB/500 g ($0.71/500 g, $1.42/500 g, $2.13/500 g, $2.84/500 g, respectively).

The attribute “quality claim” includes export quality and the Santong claim. Export quality indicates that it has been declared that the product is produced in accordance with the export standard. For instance, Dandong Yueguang Rice is sold with the label “Quality exported to Japan”, and Gong Gang Yi Hao pure milk is sold with the label “Conforms to export standard”. Santong means “Same line Same standard Same quality”. The domestic and export products of exporters are produced in the same production line following the same standards, thus achieving the same level of quality.

For the “export target market” attribute, we specified the levels as the following: Hong Kong, China (HK), Southeast Asia (SEA), European Union (EU), and no target market claim. Most foods, especially vegetables, in Hong Kong are supplied from mainland China. The top four regions with the highest value of agricultural products exported in 2019 were the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Japan, Hong Kong, and the European Union (Monthly Statistical Report of China’s Import and Export of Agricultural Products 2019, http://wms.mofcom.gov.cn/article/zt_ncp/table/2019_12.pdf, accessed on 18 May 2021).

The ASEAN and EU are also important trading partners of China for food import and export, mainly exporting vegetables and seafood. The reference level for this attribute is no target market claim, because many products sold in the market are without target market information.

The “organic” attribute has two levels (with an organic label or with no label). In the organic food production process, artificially synthesized fertilizers, pesticides, growth regulators, livestock and poultry feed additives, and genetic engineering technology are prohibited [11].

3.2. Experimental Design

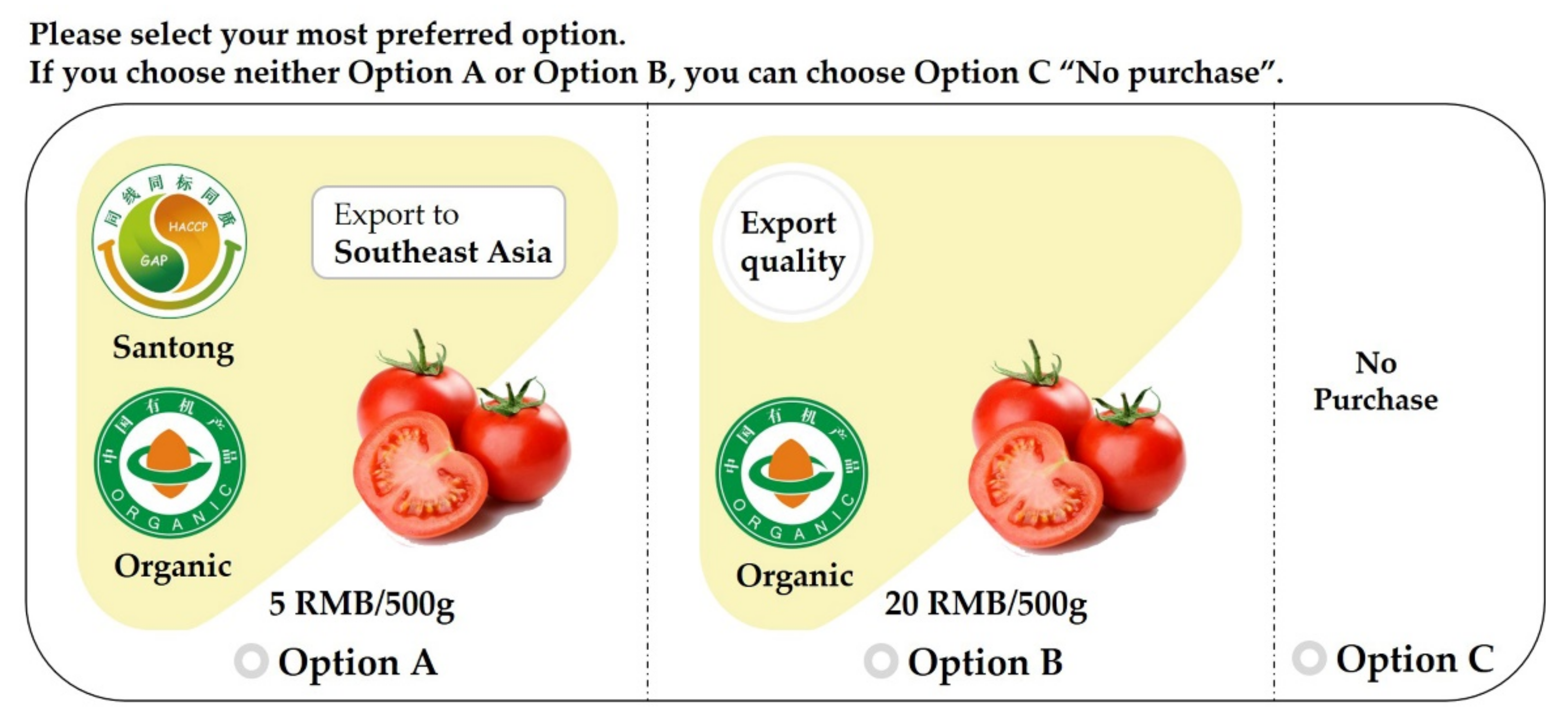

The software Stata 15.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA) was used to design the choice experiment. Based on the selected product attributes and their specific levels in Table 1, a full factorial design involves 64 (4 × 2 × 4 × 2 = 64) product profiles, and two product profiles can be randomly paired to construct a choice set. It is impossible for respondents to evaluate 2016 () choice tasks. Therefore, we used a fractional factorial design to reduce the cognitive burden on respondents, and the D-optimal criterion was used to identify the best combination of choice sets. The final choice experiment included 27 choice sets, and the D-efficiency was 98.8%. The 27 choice sets were separated into three blocks, and each block had 9 choice sets so that a respondent only needed to make decisions in 9 choice scenarios during the survey. In each choice scenario, respondents were asked to make a choice between two tomato options (tomato A and tomato B) and a “no-purchase” option. Including a “no-purchase” option presented a more realistic market scenario, where respondents could choose not to purchase a product, thereby reducing the over-inflation of the estimates [39,48]. Figure 1 presents an example of a choice set.

Figure 1.

Example of a choice set.

3.3. Data Collection and Survey Design

An online survey was conducted through Sojump (http://www.sojump.com, accessed on 18 May 2021), a professional online survey platform in China that is similar to Survey Monkey in the United States. To ensure a high quality of data, the study used the paid sample service provided by Sojump, which has more than 2.6 million registered members. The sample included all kinds of potential consumers, with diverse demographic backgrounds, from different cities in China. Sojump has been used in numerous studies for consumer research [49,50], including online choice experiment surveys [15,38].

The survey was conducted from April to May 2020 in Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Zhengzhou. The questionnaires were hosted and distributed by Sojump. Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen are the most economically developed cities in Eastern China. “Same line Same standard Same quality” was launched earlier in these three cities. Shenzhen has created its own domestic brands, such as “Korea Nongjang” and “Nature Star”, through “Same line Same standard Same quality”. Zhengzhou is one of the National Central Cities in China, and the first Santong product distribution center in China was established in the Zhengzhou Airport Economy Zone in 2019. Consumers in these cities were more likely to be aware of Santong products.

Before the online survey, we conducted a pilot survey to ensure the comprehensiveness of the questionnaires. The final questionnaire included food consumption patterns, the level of knowledge regarding food labels, the choice experiment, the consumers’ trust in food quality and food safety risk perceptions, and the respondents’ demographic characteristics.

3.4. Econometric Models

Based on the Lancaster consumer theory [51] and the random utility theory [52], consumers will choose the product with the bundle of attributes that maximizes their utility in the choice experiment. The probability of choosing an alternative will be higher if the utility provided by the alternative is the highest in a choice set. The utility of individual n choosing alternative j in situation t can be specified as follows:

where is the deterministic component and is the stochastic component. To achieve the highest utility, individual n will choose alternative j only if . Therefore, the probability of individual n choosing alternative j is given by:

Traditionally, it has been assumed that consumers are homogeneous, and conditional logit models are fitting. However, numerous studies have found that heterogeneity is important when analyzing consumer preferences for food products [53,54,55]. The random parameter logit (RPL) model is regarded as a highly flexible model that can approximate any random utility model [56], to account for heterogeneity in consumer preferences. Under RPL, is assumed to be a linear function of attributes including price, quality claim, export target market and organic status in the study. can be expressed as follows:

where is the coefficient to be estimated and represents the kth attribute of alternative j in a choice set t.

According to Train [57], the probability that individual n chooses alternative j in situation t is specified as:

where we can specify the distribution of the random parameter .

The results from Equation (3) are used to calculate consumers’ marginal WTP for the kth product attribute, which is expressed as:

where is the estimated parameter of the non-price attribute k and is the estimated price coefficient.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Characteristics of the Sample

In total, 779 questionnaires were received through the sampling service. We obtained 714 valid responses after dropping invalid responses, such as those with the same answers to all questions or that had the same Internet Protocol (IP) address. We also discarded the questionnaires if the respondent was younger than 18 years old. Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the sample. The sample included 50.70% male and 49.30% female respondents. Regarding age, 35.01% of the respondents were between 30 and 39 years old. Most of the respondents had a college degree (65.41%), and the median household monthly income was between 15,001 and 20,000 RMB. About 71.99% of the respondents were married. In addition, about 88.38% of the respondents identified themselves as the primary food shoppers in their households. The respondents were relatively young and their education levels were relatively high. The reason may be that young and well-educated people are more likely to complete an online questionnaire. The sample characteristics are consistent with previous studies that used the Sojump survey platform in China [15,50]. The consumers’ knowledge of Santong products is also measured using a five-point Likert scale (the agree/disagree anchor points) and the mean score of their knowledge is 2.78.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics (N = 714).

4.2. Random Parameter Logit Results

The results of the RPL model are presented in Table 3. The RPL model was estimated using Stata 15.1 with 2000 Halton draws. The coefficients for the no-buy option, price and the interaction terms are assumed to be fixed, and the coefficients of other attributes are random and follow a normal distribution [13,39,53]. As shown in Table 3, the coefficients for the no-buy option and price were negative and statistically significant at the 1% level, which was consistent with our expectations.

Table 3.

Results of the Random Parameter Logit.

Regarding the main effects, compared to the self-declared claim “export quality”, the coefficient of Santong is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that Chinese consumers show a positive preference for Santong products. With respect to the export target market attribute, the mean estimate of the EU coefficient was positive at the 1% significance level, but the coefficients of HK and SEA were not statistically significant. One possible explanation is that both Hong Kong and Southeast Asia are Asian markets, so that there is no difference in consumers’ perception of utility compared to products without an export target market claim. Products with the export target market “EU” were preferred by consumers. As for the organic certification attribute, products without organic certification are used as the reference level. The mean estimate of the organic coefficient is positive and highly significant, indicating that products with organic certification are more likely to be chosen.

In terms of the interaction effects, we find that the interaction terms between the Santong claim and organic certification (Santong × Organic) are significantly negative, while the interaction effect between the Santong claim and the export target market (Santong × HK, Santong × SEA, Santong × EU) are not significant. Our results show that the Santong claim and organic certification are substituted for each other, which means adding organic certification to Santong food products does not improve consumers’ utility linearly. The co-existence of a Santong claim and organic certification generates a discounting effect. One reason may be that consumers might perceive the values to be overlapping when these two attributes are presented simultaneously. Another reason could be that it causes consumer confusion, and increases the cost of information processing, i.e., information overload, which reduces utility.

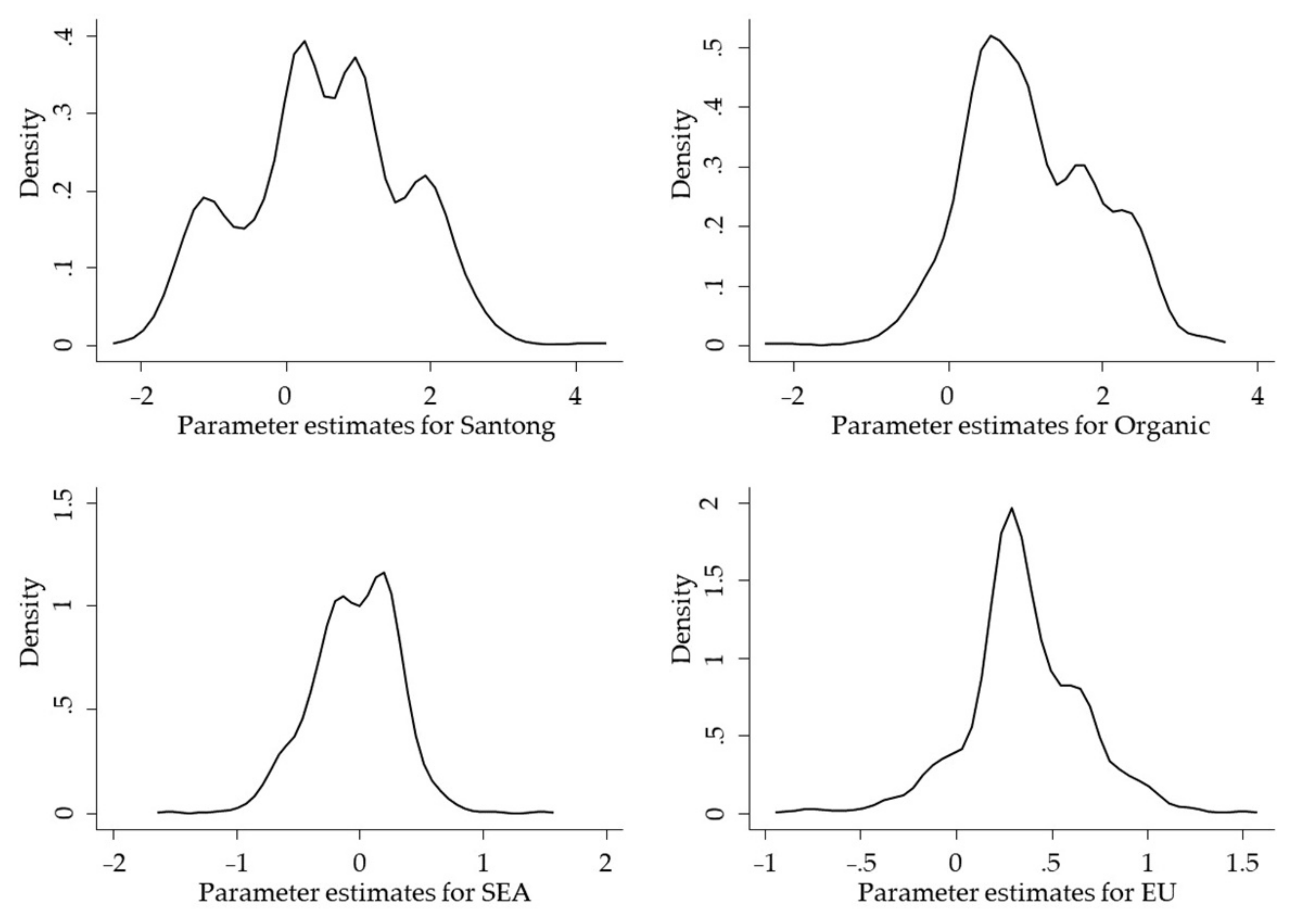

In addition, the RPL model revealed both population and individual preferences. Most standard deviation estimates of the random parameters are highly significant except in the case of HK, indicating heterogeneous preferences for organic certification among our sample, which is consistent with previous literature on consumers’ heterogeneous preferences for organic labels [3,28,55]. Moreover, we also found that consumer preferences for the Santong claim and the export target market “EU” are heterogeneous. Using the estimated parameters in the RPL model, we can calculate the proportion of respondents who prefer a specific attribute [58]. We found that 69% of the respondents preferred the Santong claim and export target market “EU”, and 84% of the respondents preferred organic certification. These percentages are calculated by , where Φ is the cumulative standard normal distribution. Furthermore, following Revelt and Train [59], we first reported the RPL model with only the main effect included (see Appendix A Table A1), and derived its individual-level parameter distribution using kernel density plots. As is shown in Figure 2, the kernel density plots for Santong and organic status have multiple peaks, which provides evidence of heterogeneous preferences. The kernel density plot for Santong shows negative values with one peak below zero, which corresponds to the smaller mean coefficient of Santong. The reason may be that many consumers still have low knowledge about Santong products. About 44% of the respondents expressed a low level of knowledge about Santong products in our survey (Consumers’ knowledge about Santong products is measured using a five-point Likert scale: How much do you know about “Same line Same standard Same quality” (Santong) products?). The kernel density plots for SEA and EU attributes also show heterogeneity in consumer preferences. Note that the mean effect of SEA is not significant, while the standard deviation is significant. Given the normality assumption, this result implies that about half of the respondents placed a positive value on SEA and half a negative value.

Figure 2.

Individual-level parameter distribution.

4.3. Marginal Willingness to Pay

Based on the estimation results of the RPL model, the marginal WTP can be calculated following Equation (5). Table 4 presents the estimated mean and 95% confidence intervals of WTP for the attributes. Compared to tomatoes with the self-declared claim “export quality”, tomatoes with the Santong claim would receive a premium of 3.99 RMB per 500 g. Consumers showed the highest WTP for tomatoes with Chinese organic certification (6.91 RMB per 500 g). Consumers were willing to pay a premium of 1.79 RMB per 500 g for tomatoes carrying the export target market claim “EU”. However, we did not find a premium for the export target market claim “HK” and “SEA” (WTP estimates are not statistically significant).

Table 4.

Results of consumers’ willingness-to-pay assessment.

In addition, there are substitution effects when the products are labeled as both Santong and organic. Consumers were willing to pay 1.69 RMB per 500 g less than the total premiums for both attributes. WTP for the combination of the two attributes, which had a significant interaction effect, can be calculated as the sum of the individual WTP and that of their interaction terms [44]. Compared to tomatoes without any Santong claim and an organic label, the combined premium for the combination of Santong and organic labels is 9.21 RMB per 500 g (3.99 + 6.91 − 1.69 = 9.21). This result suggests that a higher product premium can be obtained by using both Santong and organic labels simultaneously.

5. Discussion

This study conducted a choice experiment to investigate Chinese consumer preferences and their willingness to pay more for Santong food products, and the influences of Santong, export target market and organic certification labeling on consumers’ purchasing choices.

First, compared to the self-declared claim “export quality”, consumers prefer the Santong claim. Previous studies have indicated that consumers pay attention to food products with production claims, including production systems, production methods and processing methods [60,61,62,63,64]. Asante-Addo and Weible [65] reported that consumer utility increases when an antibiotic/hormone-free claim is made for a meat product. Yang et al. [66] found that consumers prefer the production claim “Wild” rather than “Farmed” when they assessed consumer willingness to pay for Arctic food products. As a production claim, Santong labeling means that products are produced on one production line following the same standards and the same quality requirements for both foreign and domestic markets. Our result confirms that Chinese consumers are willing to pay a premium for the Santong claim. In this case, products that comply with the criteria for the use of the Santong label could be a promising avenue when foreign trade enterprises sell export products in the domestic market. However, the individual-level parameter estimates indicate that many respondents are still not willing to pay more for Santong products. Our survey shows that 69% of the respondents preferred Santong products, while 44% of the respondents still had a low level of knowledge about Santong. The introduction of additional information to further knowledge will generally increase consumer WTP [67,68,69].

Second, products with the export target market “EU” are preferred by consumers, while there is no significant difference between export target markets “HK” and “SEA”. Consumer preferences for the destination of the export market may be interpreted by the findings of region-of-origin or country-of-origin effects. Consumers believe that the country of origin is linked to quality [70]. Generally, food products sourced from economically developed countries are more preferred by consumers rather than those from less developed countries [4,29]. Yin et al. [30] found that Chinese consumers prefer food products produced in the European Union. Chinese consumers generally believe that the quality of Chinese products is lower than those originating from developed countries, mainly because China, as a developing country, is limited by relatively outdated technology and management. In our study, products with the export target market “EU” were produced and sold domestically following the quality standards requirements of the European Union, and consumers show positive preferences for those products which could be exported to the European Union. Our results indicate that consumers may prefer food quality and safety production standards of a developed country (region), no matter where the food products were produced. It is interesting that Santong food products may have a “destination effect” which is similar to the “origin effect”.

Third, consumers show the highest WTP for organic attribution, and 84% of respondents expressed positive preferences for organic certification. This result is in consonance with those found by other researchers [15,38,42,71,72], who reported that consumers show greater preferences for organic food products than for conventional ones. The standards of organic production are widely known to consumers [73], and Chen et al. found that Chinese consumers are willing to pay for tomatoes carrying organic labels from different countries/regions [43]. We also examined the interaction effects between the Santong claim and organic certification and found substitution effects between them. As a quality attribute, previous studies found that organic certification and other quality cues may be substitutes. According to Yin et al., the organic label and traceability information may be interchangeable, which means that adding traceability information to organic foods may not improve consumer utility [28]. The substitution effects are also found between organic certification and local production claims [44]. In our study, the results of WTP estimates also show that the substitution effects between organic certification and Santong claims are relatively small.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Managerial Implications

The findings of this research have implications for both Chinese exporters and the government, especially after the shock impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on consumers’ positive preferences and their willingness to pay for the Santong claim, exporters may benefit from applying the Santong program through producing goods on the same production line, following the same standards and quality requirements for both foreign and domestic markets. With the support of the platform built by the government, exporters can make up for the lack of brands or channels in domestic sales. It is noteworthy that consumers are more likely to choose products with an export target market of developed regions. Consumers may prefer food products that conform to higher quality standards, no matter where they are produced. Additionally, although the co-existence of the Santong claim and organic certification may generate a discounting effect in consumers’ perceived utility, exporters may still increase price premiums through organic certification, due to the relatively small substitution effects.

From the policy perspective, on the one hand, with the consumption upgrade in the domestic market, consumers’ demand for high-quality food products could not be satisfied. On the other hand, Chinese exporters face increasing risks from foreign trade due to the weakening of international market demand, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic. The Santong program may be an effective solution to improve perceived food quality domestically. The Chinese government should support exporters that produce and sell Santong food products domestically and strengthen the publicity of Santong. For instance, a series of promotional activities (e.g., “Santong entering ten thousand homes” and “Santong shopping festival”) should be carried out continuously. At the same time, the Chinese solution “Same line Same standard Same quality” to improve food quality in the domestic market may have implications for other emerging markets. The domestic demand for safer food is increasing with consumers’ higher incomes, and consumers tend to pay more attention to food quality rather than just quantity. In this case, governments should implement measures to improve the level of food quality in the domestic market.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

Our study also has certain limitations that can inspire future research. First, there are other attributes that can affect consumer preferences for Santong food products, such as branding and place of sale. Future studies should consider the influence of these attributes. Second, our sample is limited to consumers from four cities in China (Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Zhengzhou), which is not representative of general Chinese consumers, so future studies should be conducted in multiple cities with a wider range of consumers, to test the robustness of our findings. Finally, we conducted choice experiments through an online survey, and thus face the challenge of hypothetical bias associated with stated preference methods [74]. Given that consumers’ purchasing intentions may not always translate into actual purchasing, future studies can use the auction or real choice experiments to improve WTP estimates.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.B. and Z.Z.; methodology, L.B. and T.Z.; software, T.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, L.B.; writing—review and editing, L.B., Z.Z. and T.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (SKCX2018001), and a project funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

RPL model with only the main effects.

Table A1.

RPL model with only the main effects.

| Variables | Coef. | Std. Err. | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main effects | |||

| Price | −0.1747 *** | 0.005 | 0 |

| Nobuy | −2.6088 *** | 0.085 | 0 |

| Santong | 0.5276 *** | 0.078 | 0 |

| HK | 0.0037 | 0.065 | 0.954 |

| SEA | −0.0423 | 0.079 | 0.593 |

| EU | 0.3702 *** | 0.074 | 0 |

| Organic | 1.0749 *** | 0.065 | 0 |

| Standard deviation | |||

| Santong | 1.4442 *** | 0.078 | 0 |

| HK | −0.184 | 0.31 | 0.553 |

| SEA | −0.7643 *** | 0.14 | 0 |

| EU | 0.6871 *** | 0.124 | 0 |

| Organic | 1.1739 *** | 0.071 | 0 |

| Number of respondents | 714 | ||

| Number of observations | 19278 | ||

| Log likelihood | −4858.5599 | ||

| AIC | 9741.12 | ||

| BIC | 9835.52 | ||

| LR chi2 (5) | 629.58 | ||

| Prob > chi2 | 0 | ||

Note: *** indicates that p < 0.01.

References

- My, N.H.; Rutsaert, P.; Van Loo, E.J.; Verbeke, W. Consumers’ familiarity with and attitudes towards food quality certifications for rice and vegetables in Vietnam. Food Control 2017, 82, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Gao, Z.; Snell, H.A.; Ma, H. Food safety concerns and consumer preferences for food safety attributes: Evidence from China. Food Control 2020, 112, 107157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Veeman, M.M. Chinese consumers’ preferences for quality signals on fresh milk: Brand versus certification. Agribusiness 2019, 35, 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Gao, Z.; Heng, Y.; Shi, L. Chinese consumers’ preferences for food quality test/measurement indicators and cues of milk powder: A case of Zhengzhou, China. Food Policy 2019, 89, 101791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, L.; Yanagishima, K.; Li, X.; Li, P.; Nakagawa, M. Food safety regulation and its implication on Chinese vegetable exports. Food Policy 2015, 57, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ittersum, K.; Candel, M.J.; Meulenberg, M.T. The influence of the image of a product’s region of origin on product evaluation. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, M.L.; Umberger, W.J. A choice experiment model for beef: What US consumer responses tell us about relative preferences for food safety, country-of-origin labeling and traceability. Food Policy 2007, 32, 496–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.H.; Hu, W.; Maynard, L.J.; Goddard, E.U.S. Consumers’ Preference and Willingness to Pay for Country-of-Origin-Labeled Beef Steak and Food Safety Enhancements. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2003, 61, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro, A.; Rubio, S.; Miranda, F.J. The region-of-origin (ROO) effect on purchasing preferences: The case of a multiregional designation of origin. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 820–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongprawmas, R.; Canavari, M. Consumers’ willingness-to-pay for food safety labels in an emerging market: The case of fresh produce in Thailand. Food Policy 2017, 69, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Pieniak, Z.; Verbeke, W. Consumers’ attitudes and behaviour towards safe food in China: A review. Food Control 2013, 33, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Wang, H.H.; Ortega, D.L.; Widmar, N.J.O. Factoring Chinese consumers’ risk perceptions into their willingness to pay for pork safety, environmental stewardship, and animal welfare. Food Control 2018, 85, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Hu, W.; Chen, Y.; Han, F.; Wang, Y.; Chen, M. Chinese consumer preferences for fresh produce: Interaction between food safety labels and brands. Agribusiness 2018, 35, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Yin, S.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Z. Consumers’ willingness to pay for tomatoes carrying different organic labels: Evidence from auction experiments. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 2814–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Hu, B.; Xiong, J. Understanding Heterogeneous Consumer Preferences in Chinese Milk Markets: A Latent Class Approach. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 71, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagalj, M.; Haas, R.; Morawetz, U.B. Effects of quality claims on willingness to pay for organic food: Evidence from experimental auctions in Croatia. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 2218–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldrop, M.E.; McCluskey, J.J.; Mittelhammer, R.C. Products with multiple certifications: Insights from the US wine market. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2017, 44, 658–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, B.; Camanzi, L. Nutrition, hedonic or environmental? The effect of front-of-pack messages on consumers’ perception and purchase intention of a novel food product with multiple attributes. Food Res. Int. 2020, 130, 108962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karstens, B.; Belz, F.M. Information asymmetries, labels and trust in the German food market: A critical analysis based on the economics of information. Int. J. Advert. 2006, 25, 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klopčič, M.; Slokan, P.; Erjavec, K. Consumer preference for nutrition and health claims: A multi-methodological approach. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 82, 103863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcombe, K.; Bradley, D.; Fraser, I.; Hussein, M. Consumer preferences regarding country of origin for multiple meat products. Food Policy 2016, 64, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebitus, C.; Peschel, A.O.; Hughner, R.S. Voluntary food labeling: The additive effect of “free from” labels and region of origin. Agribusiness 2018, 34, 714–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-C.; Chen, C.-W.; Chen, H.-S. Measuring Consumer Preferences and Willingness to Pay for Coffee Certification Labels in Taiwan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loo, E.J.; Grebitus, C.; Roosen, J. Explaining attention and choice for origin labeled cheese by means of consumer ethno-centrism. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 78, 103716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, T.; Kashiwagi, K.; Isoda, H. Effect of Religious and Cultural Information of Olive Oil on Consumer Behavior: Evidence from Japan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebitus, C.; Menapace, L.; Bruhn, M. Consumers’ use of seals of approval and origin information: Evidence from the German pork market. Agribusiness 2011, 27, 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; Pedersen, S.; Paternoga, M.; Schwendel, E.; Aschemann-Witzel, J. How important is country-of-origin for organic food consumers? A review of the literature and suggestions for future research. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 542–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Lv, S.; Chen, Y.; Wu, L.; Chen, M.; Yan, J. Consumer preference for infant milk-based formula with select food safety information attributes: Evidence from a choice experiment in China. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2018, 66, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; Pedersen, S.; Aschemann-Witzel, J. The impact of organic certification and country of origin on consumer food choice in developed and emerging economies. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 72, 10–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, M.; Wang, Y. Consumer preference and willingness to pay for the traceability information attribute of infant milk formula: Evidence from a choice experiment in China. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 1276–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Gao, Z.; Swisher, M.; Zhao, X. Consumers’ preferences for fresh broccolis: Interactive effects between country of origin and organic labels. Agric. Econ. 2015, 47, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Yu, X.; Li, C.; McFadden, B.R. The interaction between country of origin and genetically modified orange juice in urban China. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 71, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yan, Z.; Zhou, J. Consumer Choices and Motives for Eco-Labeled Products in China: An Empirical Analysis Based on the Choice Experiment. Sustainability 2017, 9, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ge, J.; Ma, Y. Urban Chinese Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Pork with Certified Labels: A Discrete Choice Experiment. Sustainability 2018, 10, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzocchi, C.; Orsi, L.; Sali, G. Consumers’ Attitudes for Sustainable Mountain Cheese. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Chu, F. Organic vs. non-organic food products: Credence and price competition. Sustainability 2017, 9, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Chu, F.; Dolgui, A.; Chu, C.; Zhou, W.; Piramuthu, S. Recent advances and opportunities in sustainable food supply chain: A model-oriented review. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 5700–5722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Liu, Q.; Mao, R.; Yu, X. Habit spillovers or induced awareness: Willingness to pay for eco-labels of rice in China. Food Policy 2017, 71, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Gao, Z.; Nayga, R.M., Jr.; Snell, H.A.; Ma, H. Consumers’ valuation for food traceability in China: Does trust matter? Food Policy 2019, 88, 101768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Shi, L.; Gao, Z.; House, L. The impact of customer ratings on consumer choice of fresh produce: A stated preference experiment approach. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 68, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Hamm, U. Governmental and private certification labels for organic food: Consumer attitudes and preferences in Germany. Food Policy 2014, 49, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Yin, S.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, D. Effectiveness of China’s Organic Food Certification Policy: Consumer Preferences for Infant Milk Formula with Different Organic Certification Labels. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2014, 62, 545–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wang, Y.; Yin, S.; Hu, W.; Han, F. Chinese consumer trust and preferences for organic labels from different regions: Evidence from real choice experiment. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 1521–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meas, T.; Hu, W.; Batte, M.T.; Woods, T.A.; Ernst, S. Substitutes or Complements? Consumer Preference for Local and Organic Food Attributes. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2014, 97, 1044–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, D.L.; Wolf, C.A. Demand for farm animal welfare and producer implications: Results from a field experiment in Michigan. Food Policy 2018, 74, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallas, Z.; Lambarraa, F.; Gil, J.M.; Calot, Z.K. A stated preference analysis comparing the Analytical Hierarchy Process versus Choice Experiments. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccia, F.; Sarnacchiaro, P. Chi-squared automatic interaction detector analysis on a choice experiment: An evaluation of responsible initiatives on consumers’ purchasing behavior. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1143–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britwum, K.; Yiannaka, A. Consumer willingness to pay for food safety interventions: The role of message framing and issue involvement. Food Policy 2019, 86, 101726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhong, C. Factors driving consumption behavior for green aquatic products: Empirical research from Ningbo, China. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 1442–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, N.; Li, L.; Ling, S.; Ma, S.; Yao, W. Influence of attitudinal and low-carbon factors on behavioral intention of commuting mode choice—A cross-city study in China. Transp. Res. Part. A Policy Pract. 2018, 111, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, K.T. A New Approach to Consumer Theory. J. Polit. Econ. 1966, 74, 132–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, D. Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. In Frontiers in Econometrics Academic; Zarembka, P., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974; pp. 105–142. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, D.L.; Wang, H.H.; Wu, L.; Olynk, N.J. Modeling heterogeneity in consumer preferences for select food safety attributes in China. Food Policy 2011, 36, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.B.; Moon, W.; Balasubramanian, S.K. Consumer valuation of health attributes for soy-based food: A choice modeling approach. Food Policy 2012, 37, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loo, E.J.; Caputo, V.; Nayga, R.M., Jr.; Verbeke, W. Consumers’ valuation of sustainability labels on meat. Food Policy 2014, 49, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, D.; Train, K. Mixed MNL models for discrete response. J. Appl. Econ. 2000, 15, 447–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Train, K.E. Discrete Choice Methods with Simulation; Cambridge Book; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003; pp. 1–388. [Google Scholar]

- Erdem, S. Consumers’ Preferences for Nanotechnology in Food Packaging: A Discrete Choice Experiment. J. Agric. Econ. 2015, 66, 259–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revelt, D.; Train, K. Customer-Specific Taste Parameters and Mixed Logit; Working Paper; Department of Economics, University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dunne, C.; Siettou, C. UK consumers’ willingness to pay for laying hen welfare. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 2867–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edenbrandt, A.K.; Gamborg, C.; Thorsen, B.J. Consumers’ preferences for bread: Transgenic, cisgenic, organic or pesticide-free? J. Agric. Econ. 2018, 69, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hobbs, J.E. How do cultural worldviews shape food technology perceptions? Evidence from a discrete choice experiment. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 71, 465–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hobbs, J.E. Food values and heterogeneous consumer responses to nanotechnology. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 68, 289–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, D.L.; Lusk, J.L.; Lin, W.; Caputo, V. Predicting responsiveness to information: Consumer acceptance of biotechnology in animal products. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2020, 47, 1644–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante-Addo, C.; Weible, D. Is there hope for domestically produced poultry meat? A choice experiment of consumers in Ghana. Agribusiness 2020, 36, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hobbs, J.E.; Natcher, D.C. Assessing consumer willingness to pay for Arctic food products. Food Policy 2020, 92, 101846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Han, F.; Chen, M.; Li, K.; Li, Q. Chinese urban consumers’ preferences for white shrimp: Interactions between organic labels and traceable information. Aquaculture 2020, 521, 735047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmour, D.N.; Bazzani, C.; Nayga, R.M., Jr.; Snell, H.A. Do consumers value hydroponics? Implications for organic certification. Agric. Econ. 2019, 50, 707–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scozzafava, G.; Gerini, F.; Boncinelli, F.; Contini, C.; Marone, E.; Casini, L. Organic milk preference: Is it a matter of information? Appetite 2020, 144, 104477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, J.; Faria, F. Quest for purposefully designed conceptualization of the country-of-origin image construct. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4411–4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vapa-Tankosić, J.; Ignjatijević, S.; Kiurski, J.; Milenković, J.; Milojević, I. Analysis of Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Organic and Local Honey in Serbia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, G.; Borrello, M.; Guccione, G.D.; Schifani, G.; Cembalo, L. Organic Food Consumption: The Relevance of the Health Attribute. Sustainability 2020, 12, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldesouky, A.; Mesias, F.J.; Escribano, M. Consumer Assessment of Sustainability Traits in Meat Production. A Choice Experiment Study in Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn, J.M.; Hu, W. Understanding Hypothetical Bias: An Enhanced Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2018, 100, 1186–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).