How Brand Symbolism, Perceived Service Quality, and CSR Skepticism Influence Consumers to Engage in Citizenship Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

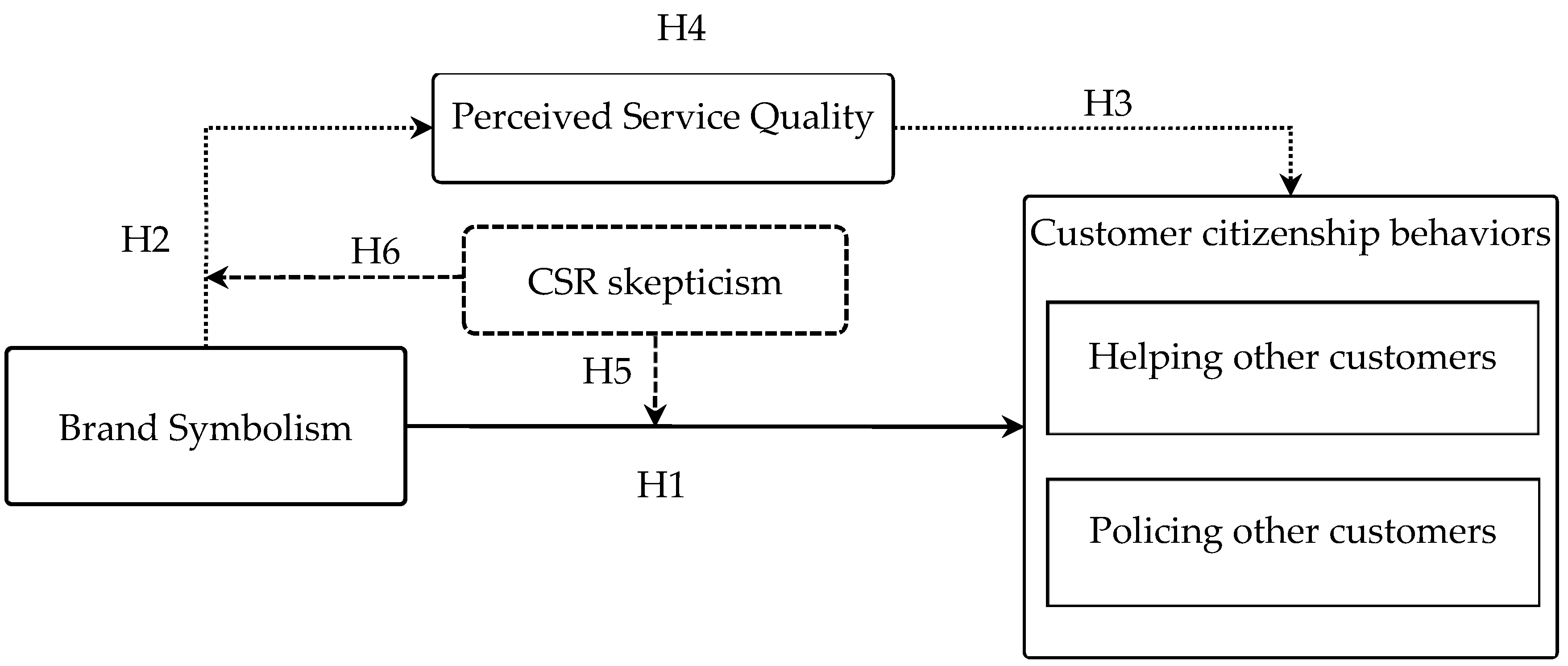

2. Theoretical Development and Hypotheses

2.1. Service-Dominant Logic Framework

2.2. Brand Symbolism and CCB

2.3. The Mediation Effect of Perceived Service Quality

2.4. The Moderating Effect of CSR Skepticism

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection Procedures

3.2. Measurements

4. Results

4.1. Validity and Reliability

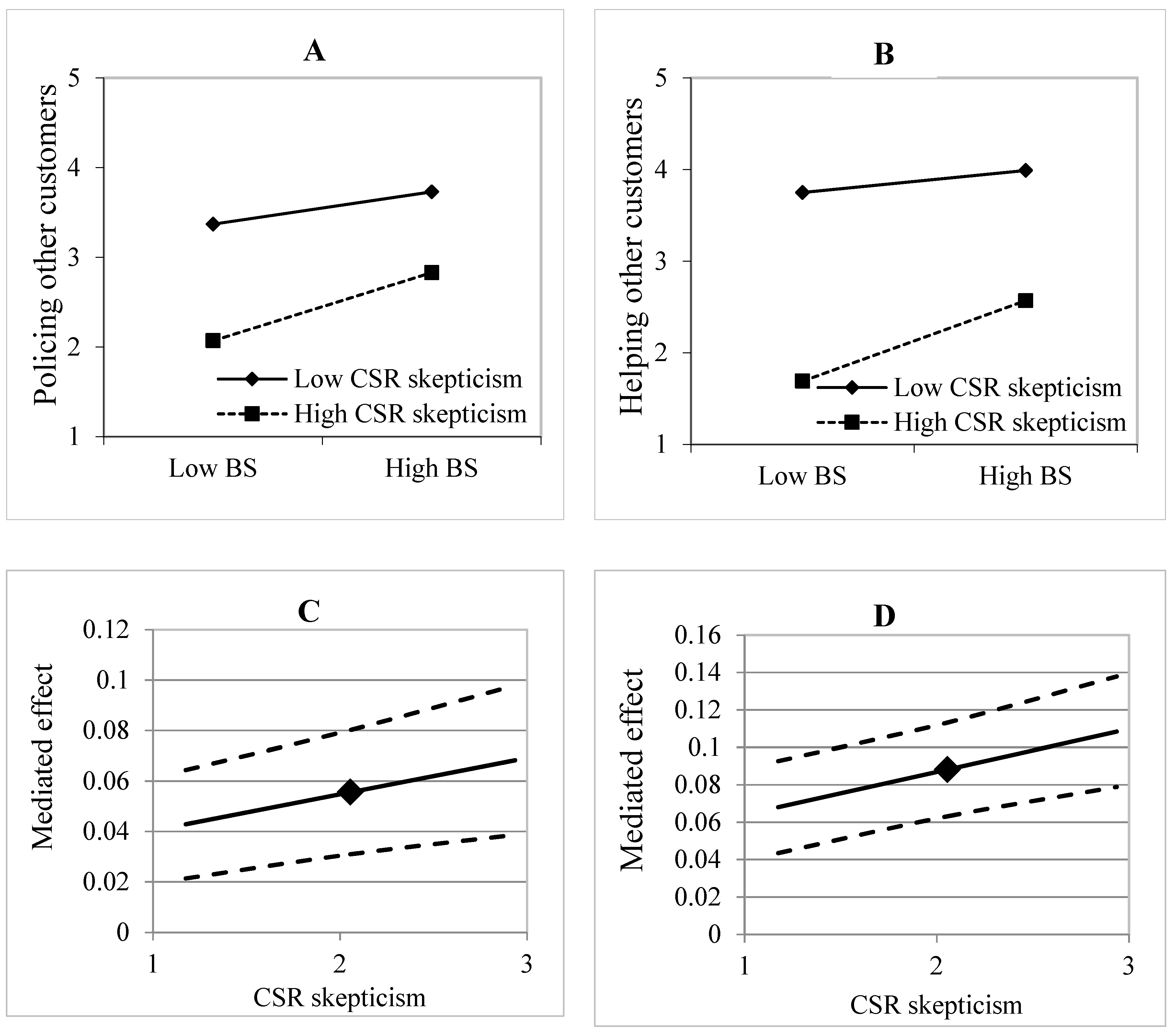

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. General Discussion

5.2. Managerial Contributions

6. Limitations and Directions for Future Studies

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global Coffee Shops Industry. Available online: https://www.reportlinker.com/p05820717/Global-Coffee-Shops-Industry.html?utm_source=PRN (accessed on 17 May 2020).

- Li, Y.; Liu, B.; Huan, T.C.T. Renewal or Not? Consumer Response to a Renewed Corporate Social Responsibility Strategy: Evidence from the Coffee Shop Industry. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljarah, A. Environmental Marketing Strategy and Customer Citizenship Behavior: An Investigation in a Café Setting. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2021, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, S. Consumers and Their Brands: Developing Relationship Theory in Consumer Research. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 24, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, J.L. Dimensions of Brand Personality. J. Mark. Res. 1997, 34, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, S.J. Symbols for Sale. In Brands, Consumers, Symbols and Research; Sage Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, S.; Reddy, S.K. Symbolic and Functional Positioning of Brands. J. Consum. Mark. 1998, 15, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lyu, S.O. Relationships among Green Image, Consumer Attitudes, Desire, and Customer Citizenship Behavior in the Airline Industry. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2020, 14, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Nguyen, H.N.; Song, H.; Chua, B.L.; Lee, S.; Kim, W. Drivers of Brand Loyalty in the Chain Coffee Shop Industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 72, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Ryu, K. The Theory of Repurchase Decision-Making (TRD): Identifying the Critical Factors in the Post-Purchase Decision-Making Process. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 786–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, E.H.; Jang, S.C.; Day, J.; Ha, S. The Impact of Eco-Friendly Practices on Green Image and Customer Attitudes: An Investigation in a Café Setting. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 41, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.; Yoo, M.; Lee, Y. A Holistic View of the Service Experience at Coffee Franchises: A Cross-Cultural Study. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 82, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.J.; Wang, J.H.; Han, H. Effect of Image, Satisfaction, Trust, Love, and Respect on Loyalty Formation for Name-Brand Coffee Shops. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 79, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Yi, Y. A Review of Customer Citizenship Behaviors in the Service Context. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 41, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.C.; Luo, S.J.; Yen, C.H.; Yang, Y.F. Brand Attachment and Customer Citizenship Behaviors. Serv. Ind. J. 2016, 36, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Poon, P.; Zhang, W. Brand Experience and Customer Citizenship Behavior: The Role of Brand Relationship Quality. J. Consum. Mark. 2017, 34, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljarah, A. The Nexus between Corporate Social Responsibility and Target-Based Customer Citizenship Behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandl, L.; Hogreve, J. Buffering Effects of Brand Community Identification in Service Failures: The Role of Customer Citizenship Behaviors. J. Bus. Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R. The Effect of Destination Social Responsibility on Tourist Environmentally Responsible Behavior: Compared Analysis of First-Time and Repeat Tourists. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keaveney, S.M. Customer Switching Behavior in Service Industries: An Exploratory Study. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, J.H.; Gabel, T.G. Symbolic Interactionism: Its Effects on Consumer Behavior and Implications for Marketing Strategy. J. Serv. Mark. 1992, 6, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengnick-Hall, C.A.; Claycomb, V.C.; Inks, L.W. From Recipient to Contributor: Examining Customer Roles and Experienced Outcomes. Eur. J. Mark. 2000, 34, 359–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljarah, A.; Alrawashdeh, M. Boosting Customer Citizenship Behavior through Corporate Social Responsibility. Does Perceived Service Quality Matter? Soc. Responsib. J. 2020. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lii, Y.-S.; Lee, M. Doing Right Leads to Doing Well: When the Type of CSR and Reputation Interact to Affect Consumer Evaluations of the Firm. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 105, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morhart, F.; Malär, L.; Guèvremont, A.; Girardin, F.; Grohmann, B. Brand Authenticity: An Integrative Framework and Measurement Scale. J. Consum. Psychol. 2013, 25, 200–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beverland, M.B.; Farrelly, F.J. The Quest for Authenticity in Consumption: Consumers’ Purposive Choice of Authentic Cues to Shape Experienced Outcomes. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 36, 838–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, B. The Antecedents and Consequences of CSR Skepticism. J. Sustain. Mark. 2020, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarmeas, D.; Leonidou, C.N.; Saridakis, C. Examining the Role of CSR Skepticism Using Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1796–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarmeas, D.; Leonidou, C.N. When Consumers Doubt, Watch out! The Role of CSR Skepticism. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1831–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Han, H.; Radic, A.; Tariq, B. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) as a Customer Satisfaction and Retention Strategy in the Chain Restaurant Sector. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.W. Human Values and Product Symbolism: Do Consumers Form Product Preference by Comparing the Human Values Symbolized by a Product to the Human Values That They Endorse? J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 2475–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Li, Y. CSR and Service Brand: The Mediating Effect of Brand Identification and Moderating Effect of Service Quality. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusch, R.F.; Vargo, S.L. Service-Dominant Logic: Reactions, Reflections and Refinements. Mark. Theory 2006, 6, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FitzPatrick, M.; Davey, J.; Muller, L.; Davey, H. Value-Creating Assets in Tourism Management: Applying Marketing’s Service-Dominant Logic in the Hotel Industry. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M. A Dual-Process Model of the Influence of Human Values on Consumer Choice. Revista Psicologia Organizações e Trabalho 2006, 6, 15–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; Milberg, S.; Lawson, R. Evaluation of Brand Extensions: The Role of Product Feature Similarity and Brand Concept Consistency. J. Consum. Res. 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, K.L.; Blodgett, J.G. Customer Response to Intangible and Tangible Service Factors. Psychol. Mark. 1999, 16, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. A Conceptual Model of Service Quality and Its Implications for Future Research. J. Mark. 1985, 49, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, M.A.; He, Y.; Vargo, S.L. The Evolving Brand Logic: A Service-Dominant Logic Perspective. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2009, 37, 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment Theory and Its Therapeutic Implications. Adolesc. Psychiatry (Hilversum) 1978, 6, 5–33. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H. Individuals and Groups in Social Psychology. Br. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, F. Attitudes and Cognitive Organization. J. Psychol. 1946, 21, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, S.P. Utility, Cultural Symbolism and Emotion: A Comprehensive Model of Brand Purchase Value. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2005, 22, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, R.; Wattanasuwan, K. Brands as Symbolic Resources for the Construction of Identity. Int. J. Advert. 1998, 17, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L. Car Use: Lust and Must. Instrumental, Symbolic and Affective Motives for Car Use. Transp. Res. Part. A Policy Pract. 2005, 39, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Jaworski, B.; Maclnnis, D. Strategic Brand Concept-Image Management. J. Mark. 1986, 50, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, M. Customers as Good Soldiers: Examining Citizenship Behaviors in Internet Service Deliveries. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Yin, X.; Lee, G. The Effect of CSR on Corporate Image, Customer Citizenship Behaviors, and Customers’ Long-Term Relationship Orientation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.; Lee, B. Pride, Mindfulness, Public Self-Awareness, Affective Satisfaction, and Customer Citizenship Behaviour among Green Restaurant Customers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 83, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, V.W.S.; Chen, P.-J.; Schuckert, M. Managing Customer Citizenship Behaviour: The Moderating Roles of Employee Responsiveness and Organizational Reassurance. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruen, T.W.; Summers, J.O.; Acito, F. Relationship Marketing Activities, Commitment, and Membership Behaviors in Professional Associations. J. Mark. 2000, 64, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaza, N.A.; Zhao, J. Encounter-Based Antecedents of e-Customer Citizenship Behaviors. J. Serv. Mark. 2013, 27, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaza, N.A. Personality Antecedents of Customer Citizenship Behaviors in Online Shopping Situations. Psychol. Mark. 2014, 31, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakopoulou, E.; Kitsios, F.; Kamariotou, M. Analyzing Consumers’ Behavior and Purchase Intention: The Case of Social Media Advertising. In Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium and 30th National Conference on Operational Research, Patras, Greece, 16–18 May 2019; pp. 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, M.R. The Role of Products as Social Stimuli: A Symbolic Interactionism Perspective. J. Consum. Res. 1983, 10, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; MacInnis, D.; Priester, J.; Eisingerich, A.; Iacobucci, D. Brand Attachment and Brand Attitude Strength: Conceptual and Empirical Differentiation of Two Critical Brand Equity Drivers. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R.W. Possessions and the Extended Self. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 139–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmar, H.; Pepper, L. To Have Is to Be: Materialism and Person Perception in Working-Class and Middle-Class British Adolescents. J. Econ. Psychol. 1994, 15, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J. Self-Concept in Consumer Behavior: A Critical Review. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. SERVQUAL: A Multiple-Item Scale for Measuring Consumer Perceptions of Service Quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R.; Chen, X. The Effects of Perceived Service Quality on Repurchase Intentions and Subjective Well-Being of Chinese Tourists: The Mediating Role of Relationship Quality. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R.A.; Tehseen, S.; Parrey, S.H. Promoting Customer Brand Engagement and Brand Loyalty through Customer Brand Identification and Value Congruity. Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2018, 22, 321–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Consumer-Company Identification: A Framework for Understanding Consumers’ Relationships with Companies. J. Mark. 2003, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnould, E.J.; Thompson, C.J. Consumer Culture Theory (CCT): Twenty Years of Research. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C. A Service Quality Model and Its Marketing Implications. Eur. J. Mark. 1984, 18, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Cortés, G. Influencia Del Consumo Simbólico En El Valor de La Experiencia y El Uso de Las Redes Sociales Virtuales. Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2017, 21, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.G.; Moon, Y.J. Customers’ Cognitive, Emotional, and Actionable Response to the Servicescape: A Test of the Moderating Effect of the Restaurant Type. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brucks, M.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Naylor, G. Price and Brand Name as Indicators of Quality Dimensions for Consumer Durables. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, L.A. Customer Voluntary Performance: Customers as Partners in Service Delivery. J. Retail. 1997, 73, 383–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bove, L.L.; Pervan, S.J.; Beatty, S.E.; Shiu, E. Service Worker Role in Encouraging Customer Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuong, L.P.T.; Ahn, Y. Service Climate and Empowerment for Customer Service Quality among Vietnamese Employees at Restaurants. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verleye, K.; Gemmel, P.; Rangarajan, D. Managing Engagement Behaviors in a Network of Customers and Stakeholders: Evidence From the Nursing Home Sector. J. Serv. Res. 2014, 17, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Managing Customer-Based Brand Equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahearne, M.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Gruen, T. Antecedents and Consequences of Customer-Company Identification: Expanding the Role of Relationship Marketing. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 574–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, K.K.F.; King, C.; Sparks, B.; Wang, Y. The Influence of Customer Brand Identification on Hotel Brand Evaluation and Loyalty Development. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R.; Chen, X. The Impact of Perceived Service Fairness and Quality on the Behavioral Intentions of Chinese Hotel Guests: The Mediating Role of Consumption Emotions. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, H.; Kim, C. Corporate Social Responsibilities, Consumer Trust and Corporate Reputation: South Korean Consumers’ Perspectives. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljarah, A.; Emeagwali, L.; Ibrahim, B.; Ababneh, B. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Really Increase Customer Relationship Quality? A Meta-Analytic Review. Soc. Responsib. J. 2018, 16, 28–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljarah, A.; Ibrahim, B. The Robustness of Corporate Social Responsibility and Brand Loyalty Relation: A Meta-Analytic Examination. J. Promot. Manag. 2020, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, H.; Kim, S. Dimensions of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Skepticism and Their Impacts on Public Evaluations toward CSR. J. Public Relat. Res. 2016, 28, 248–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What We Know and Don’t Know About Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Nazir, M.S.; Ali, I.; Nurunnabi, M.; Khalid, A.; Shaukat, M.Z. Investing in CSR Pays You Back in Manyways! The Case of Perceptual, Attitudinal and Behavioral Outcomes of Customers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-I.; Wang, W.-H. Impact of CSR Perception on Brand Image, Brand Attitude and Buying Willingness: A Study of a Global Café. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2014, 6, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. Consumer Skepticism about Quick Service Restaurants’ Corporate Social Responsibility Activities. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2020, 23, 417–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhouz, F.; Hasouneh, A. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Customer Citizenship Behavior: The Mediating Role of Customer-Company Identification and Moderating Role of Generation. J. Sustain. Mark. 2020, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bartikowski, B.; Berens, G. Attribute Framing in CSR Communication: Doing Good and Spreading the Word—But How? J. Bus. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, P.A.; Tsamakos, A.; Vrechopoulos, A.P.; Avramidis, P.K. Corporate Social Responsibility: Attributions, Loyalty, and the Mediating Role of Trust. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2009, 37, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, B.; Aljarah, A.; Sawaftah, D. Linking Social Media Marketing Activities to Revisit Intention through Brand Trust and Brand Loyalty on the Coffee Shop Facebook Pages: Exploring Sequential Mediation Mechanism. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinnoo. Starbucks Coffee Branches in Lebanon. Available online: https://rinnoo.net/en/branches-of/starbucks-coffee-4/lebanon (accessed on 17 May 2020).

- Yi, Y.; Gong, T. Customer Value Co-Creation Behavior: Scale Development and Validation. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1279–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; Nishiyama, N. Enhancing Customer-Based Brand Equity through CSR in the Hospitality Sector. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2017, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, S.; Anderson-MacDonald, S.; Thomson, M. Overcoming the ‘Window Dressing’ Effect: Mitigating the Negative Effects of Inherent Skepticism Towards Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 145, 599–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Education: Chennai, India, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometirc Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing Moderated Mediation Hypotheses: Theory, Methods, and Prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, K.p.; Chen, A.H.; Peng, N.; Hackley, C.; Tiwsakul, R.A.; Chou, C.I. Antecedents of Luxury Brand Purchase Intention. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2011, 20, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.; Park, E. Influence on the Destination Attractiveness on Perceived Value, Satisfaction, Loyalty among Japanese Tourists. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2011, 11, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisingerich, A.B.; Rubera, G.; Seifert, M.; Bhardwaj, G. Doing Good and Doing Better despite Negative Information?: The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility in Consumer Resistance to Negative Information. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Latent Variables | λ |

| CCB | |

| Helping other customers (α = 0.90, CR = 0.88, AVE = 0.72) | |

| - Assist other customers of Starbucks if they need my help. | 0.75 |

| - Help other customers of Starbucks if they seem to have problems. | 0.85 |

| - Teach other customers to use the services provided by Starbucks correctly. | 0.94 |

| Policing other customers (α = 0.87, CR = 0.86, AVE = 0.68) | |

| - Take steps to prevent problems caused by other Starbucks customers. | 0.85 |

| - Inform Starbucks if I become aware of inappropriate behavior by other customers. | 0.81 |

| - Give advice to other Starbucks customers. | 0.70 |

| Brand Symbolism (α = 0.90, CR = 0.88, AVE = 0.56) | |

| - Starbucks products provide status and prestige. | 0.69 |

| - The brand of Starbucks is more important to me than its functional qualities. | 0.62 |

| - People use Starbucks products as a way of expressing their personality. | 0.73 |

| - Starbucks is for people who want the best things in life. | 0.81 |

| - Starbucks users stand out in a crowd. | 0.81 |

| - Using Starbucks says something about the kind of person you are. | 0.81 |

| PSQ (α = 0.88, CR = 0.84, AVE = 0.52) | |

| - Starbucks has modern-looking equipment. | - |

| - When Starbucks promised to do something by a certain time, it did it. | 0.76 |

| - Starbucks provides its services at the time it promises to do so. | 0.69 |

| - Staff at Starbucks are able to tell patrons exactly when services will be performed. | 0.71 |

| - The staff of Starbucks has the knowledge to answer customers’ queries. | 0.72 |

| - The staff of Starbucks understands the specific needs of their customers. | 0.72 |

| CSR skepticism (α = 0.87, CR = 0.89, AVE = 0.73) | |

| - I do not trust Starbucks to deliver on its social responsibility promises. | 0.80 |

| - Starbucks is usually dishonest about its real involvement in social responsibility initiatives. | 0.91 |

| - In general, I am not convinced that Starbucks will fulfill its social responsibility objectives. | 0.86 |

| CR | AVE | BS | HOC | PSQ | CSR | POC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand symbolism (BS) | 0.88 | 0.56 | 0.75 | ||||

| Helping other customers (HOC) | 0.88 | 0.72 | 0.46 | 0.84 | |||

| Perceived service quality (PSQ) | 0.84 | 0.52 | 0.57 | 0.42 | 0.72 | ||

| CSR skepticism (CSR.S) | 0.89 | 0.73 | −0.51 | −0.50 | −0.36 | 0.85 | |

| Policing other customers (POC) | 0.86 | 0.68 | 0.48 | 0.747 | 0.37 | −0.46 | 0.82 |

| From→To (β) | Helping Other Customers | Policing Other Customers | PSQ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | |||

| Brand symbolism | 0.20 *** | 28 *** | 0.57 *** |

| PSQ | 0.22 *** | 0.15 * | - |

| CSR skepticism | −0.87 *** | −0.55 * | - |

| Interaction effect | β | CI low | CI High |

| BS*CSR.S→HOC | 0.16 | 0.071 | 0.261 |

| BS*CSR.S→POC | 0.10 | 0.009 | 0.185 |

| Mediation analysis | |||

| Direct effects | |||

| BS→HOC | 0.40 | 0.295 | 0.512 |

| BS→POC | 0.35 | 0.256 | 0.456 |

| Indirect effects | |||

| BS→PSQ→HOC | 0.13 | 0.079 | 0.185 |

| BS→PSQ→POC | 0.08 | 0.027 | 0.146 |

| BS→PSQ→CCB Dimensions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderator | Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |

| Policing Other Customers | Simple paths for low CSR skepticism | 0.042 | 0.021 | 0.007 | 0.091 |

| Simple paths for normal (Mean) | 0.055 | 0.024 | 0.01 | 0.107 | |

| Simple paths for high CSR skepticism | 0.068 | 0.029 | 0.012 | 0.128 | |

| Index of the conditional indirect effect | 0.014 | 0.009 | 0.001 | 0.035 | |

| Helping Other Customers | Simple paths for low CSR skepticism | 0.068 | 0.024 | 0.024 | 0.121 |

| Simple paths for normal (Mean) | 0.088 | 0.025 | 0.040 | 0.141 | |

| Simple paths for high CSR skepticism | 0.108 | 0.03 | 0.050 | 0.168 | |

| Index of the conditional indirect effect | 0.0229 | 0.0119 | 0.0033 | 0.0498 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dalal, B.; Aljarah, A. How Brand Symbolism, Perceived Service Quality, and CSR Skepticism Influence Consumers to Engage in Citizenship Behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6021. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116021

Dalal B, Aljarah A. How Brand Symbolism, Perceived Service Quality, and CSR Skepticism Influence Consumers to Engage in Citizenship Behavior. Sustainability. 2021; 13(11):6021. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116021

Chicago/Turabian StyleDalal, Bassam, and Ahmad Aljarah. 2021. "How Brand Symbolism, Perceived Service Quality, and CSR Skepticism Influence Consumers to Engage in Citizenship Behavior" Sustainability 13, no. 11: 6021. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116021

APA StyleDalal, B., & Aljarah, A. (2021). How Brand Symbolism, Perceived Service Quality, and CSR Skepticism Influence Consumers to Engage in Citizenship Behavior. Sustainability, 13(11), 6021. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116021