Abstract

With the widespread adoption of powered micromobility devices like e-scooters for transportation in recent times, there have been many associated and potentially unknown risks. While these devices have been beneficial for commuters, managing these technological risks has been a key challenge for governments. This article presents an in-depth case study of Singapore, where these devices were adopted but were eventually banned from footpaths and public paths. We focus on identifying the technological risks and the governing strategies adopted and find that the Singaporean government followed a combination of governing strategies to address the risks of safety, liability, and switching to another transportation mode. The strategy of banning the devices was undertaken after active regulation and prudent monitoring. Based on the Singapore case, we offer policy recommendations for robust infrastructure and policy capacity, government stewardship and inclusive participatory policymaking for safe deployment, and simultaneous adoption of governing strategies to adopt these devices. The regulatory lessons from the case of Singapore can be insightful for policy discussions in other countries that have already adopted or are considering the introduction of powered micromobility devices.

Keywords:

micromobility; powered micromobility devices; risk; governance; Singapore; case study; safety 1. Introduction

The proliferation of various light vehicles that are being used for private or shared use has made micromobility a revolution in transportation and urban mobility [1]. Theoretically, micromobility constitutes all passenger trips of less than 8 km (5 miles), which account for as much as 50 to 60 percent of today’s total passenger miles travelled in China, European Union, and United States [2]. Micromobility devices can be both human-powered or assisted by electricity [3]. The powered micromobility devices comprising electric scooters or e-scooters, e-bikes, hoverboards, electric unicycles, and e-skateboards have recently become popular. They can solve problems of urbanisation such as congestion and environmental pollution, and are particularly helpful in solving the first-mile and the last mile-problem (ibid.). Due to the electric motor in powered micromobility devices, there are no tailpipe emissions, unlike other transportation modes that use thermic motors [4]. There is a clear advantage for micromobility devices in efficiency, productivity, and saving travel time compared to alternative means of transport which is crucial for building sustainable forms of transport [5]. However, the risks of using them have also manifested in many countries where such devices have been adopted.

There is growing literature on the implications of these devices, especially e-scooters. There have been studies on the risks from the use of e-scooters [6] and the varied nature of injuries [7,8,9,10,11,12]. There have particularly been safety issues like fractures, head injuries, and soft tissue injuries from accidents involving micromobility devices [6,12,13,14]. Issues surrounding Privacy and liability have also been cited in the use of micromobility devices offered, particularly by e-scooter sharing companies [15,16]. Thus, regulating these devices has proven to be a challenging task for governments [3]. Managing the technological risks of these devices is imperative to understand their differential benefits amongst segments of the society, uncertainty in policymaking, and drawbacks in policy responses to policy problems [17]. A comprehensive study of a specific case can through light on these issues, enabling jurisdictions that are likely to adopt these devices or already have, to learn from the existing policy responses.

The case of Singapore is interesting to study the governance of powered micromobility devices. In a bid to make Singapore ‘car-lite’, a slew of initiatives took place to encourage and make their adoption easier. Singapore remained one of the countries to embrace the devices at a time when some cities in the world like New York, Tokyo, and London had a partial or total ban [18]. However, as the situation evolved in Singapore, regulations were imposed to deal with the risks related to adopting these devices, and they were finally banned from footpaths in April 2020. This article evaluates the governance of technological risks of powered micromobility devices in Singapore. It addresses two major research questions—first, what were the technological risks in adopting powered micromobility devices in Singapore? Second, how did the government manage those risks? By undertaking a traditional literature review and using the Factiva database, we describe the evolution in the regulatory landscape of powered micromobility devices in Singapore. We use the insights from this to analyse the risks of adopting these devices and the mix of governing strategies used by the government.

This article is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the methodology and presents a background of micromobility devices with reasons for Singapore being an appropriate case to study governing strategies of micromobility devices. Section 3 presents an in-depth case description. Section 4 explains the risks identified with the operation of the devices and presents a discussion of the governing strategies to overcome the risks. Section 5 discusses the findings. Section 6 proposes the following policy recommendations for adoption of powered micromobility devices: (i) adoption of control-oriented, toleration-oriented, and adaptation-oriented governing strategies, (ii) strengthening infrastructure and policy capacity, (iii) inclusive participatory policymaking and (iv) government stewardship for a holistic approach to resolve problems. We conclude with Section 7.

2. Methodology, Background, and Motivation

We followed three steps for this case study research: first, for the background on micromobility devices, we searched SCOPUS and Google Scholar by using specific keywords. For a background on micromobility devices, we used the keywords in Table 1.

Table 1.

Keywords for literature review.

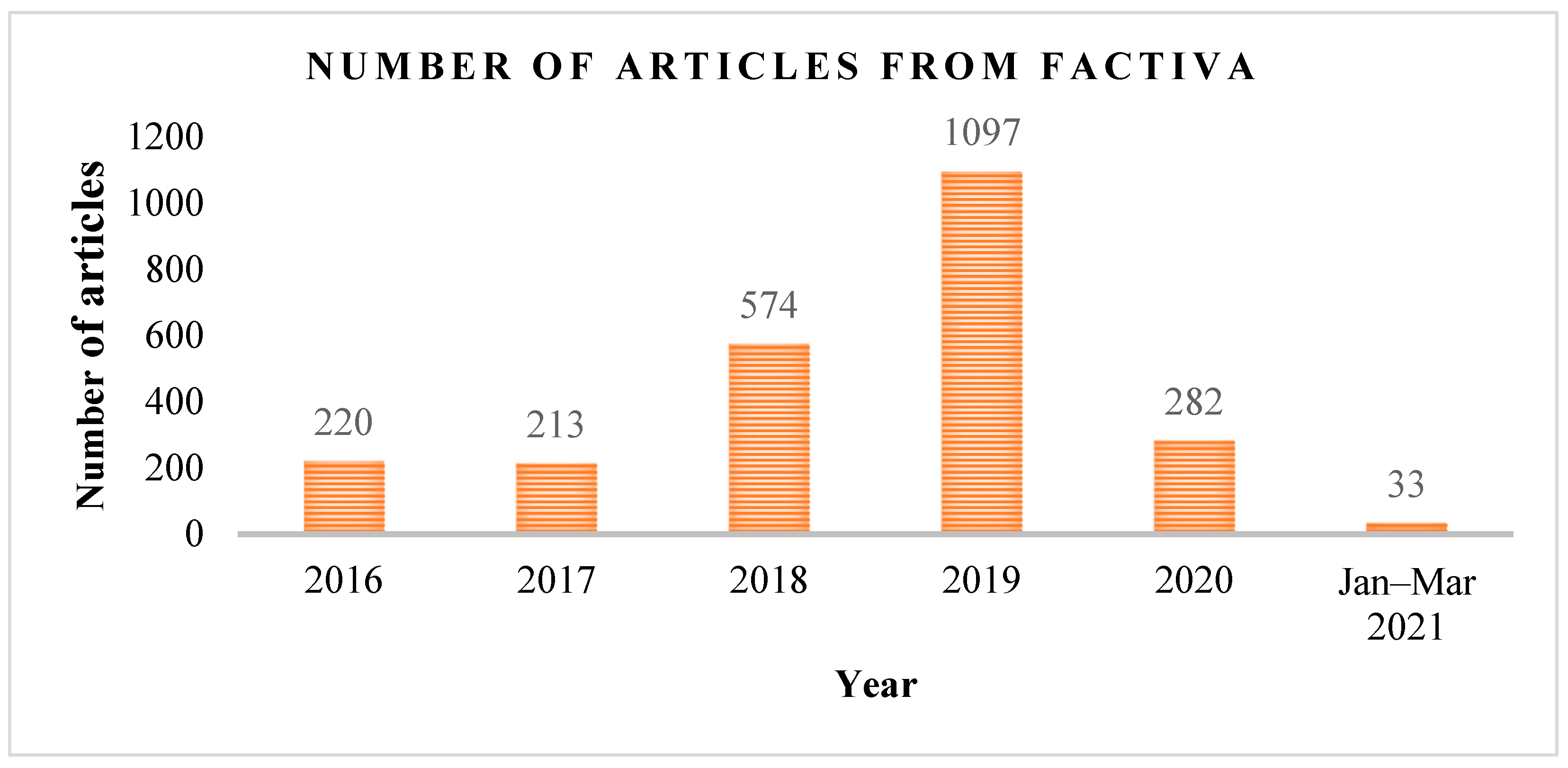

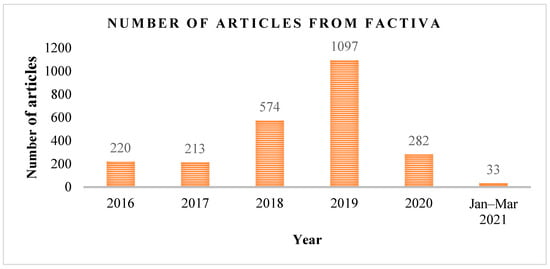

Second, we gleaned through newspaper articles for information on micromobility devices in Singapore. To do this, we used Factiva and used the search string—“PMDs OR e-scooters OR electric scooters AND Singapore” to collect newspaper articles from January 2016 to March 2021. A total of 2419 articles were provided by Factiva for this search string (see Figure 1 for the details about the number of articles). The large number of articles in 2019 indicates the focus on powered micromobility devices when a slew of regulations was undertaken. The newspaper articles were scrutinized for process tracing which helped in providing a timeline of events related to micromobility devices in Singapore. A detailed reading of newspaper articles enabled a description of the events, policy intentions of the government, dynamics between actors, and policy instruments used. Based on secondary research, a case description in chronological order is elaborated for the period of analysis.

Figure 1.

Number of articles extracted from Factiva.

After synthesising the information about the micromobility landscape in Singapore, we analyse the case by identifying the technological risks and use the framework of [16] to explain the governing strategies used by the government in Singapore to overcome the risks arising from the adoption of micromobility devices.

The definition of micromobility is broad at the moment as the devices that can be classified under micromobility are still evolving and cannot be limited to a certain type of vehicle [3]. The International Transport Forum identifies micromobility as the use of micro-vehicles that are defined as vehicles with a weight of more than 350 kg and a design speed of a maximum of 45 km/h [1]. While there is no international classification of micro-vehicles, the SAE International defines a powered micromobility vehicle as a wheeled vehicle that must (1) be fully or partially powered, (2) have a curb weight less than or equal to 227 kg and (3) have a top speed less than or equal to 48 km/h [19] (see Supplementary material A Figure S1 for a visual depiction of powered micromobility devices). The SAE International was also known as the Society of Automotive Engineers and is an association based in the United States that develops standards and is a professional association for engineers in different industries. Powered bicycles, powered standing scooters, powered seated scooters, powered self-balanced boards, and powered skates are the various types of powered micromobility vehicles designed for one person except when designed for more, with an electric or combustion power source (ibid).

Motor vehicles in Singapore comprise car and station wagons, taxis, motorcycles and scooters, goods vehicles (for light goods, heavy goods, goods and passengers) and buses. In 2020, taxis, buses, and private hire cars made up for 11 per cent of all motor vehicles, while motorcycles and scooters, goods and other vehicles, and cars had a share of 15 percent, 17 percent, and 58 percent, respectively [20]. In Singapore, regulations related to powered micromobility devices are handled by the Land Transport Authority (LTA). LTA is the statutory board in the Ministry of Transport responsible for planning, designing, building, and maintaining the land transport system and related infrastructure in Singapore [21]. Micromobility devices are classified within active mobility devices in Singapore. LTA considers the following as active mobility devices: bicycles, power-assisted bicycles, or e-bikes, motorised and non-motorised personal mobility devices (PMDs) like kick-scooters, electric scooters, hoverboards, unicycles, etc., and personal mobility aids (PMAs) [22]. In this article, we focus on the powered active mobility devices only. The rationale for this is twofold. First, powered micromobility devices like e-scooters and e-bikes are being used extensively worldwide [3,20,21]. In Singapore, from the 100,000 registered e-scooters, there were 7000 registrations from food delivery riders of three major companies—Deliveroo, GrabFood and Foodpanda [23]. Second, due to their prevalence, bike-sharing and e-scooter sharing companies have also proliferated. In Singapore, with initial permission for a few companies to operate in specified areas, 14 companies finally applied for a sandbox licensing framework. However, the licensing regime was cancelled after the ban on the operation of PMDs on footpaths.

The case study approach is suitable for the research questions in this study [24]. To study how the governance of risks arising from the adoption of powered micromobility devices, Singapore is an appropriate case due to the following reasons that satisfy the requirements of case selection: first, micromobility devices became popular in Singapore way before in other countries and the Singapore government was pro-active in monitoring the risks over time; second, powered micromobility devices are a practical alternative to cars for short distances in Singapore where the priority of the government has been to encourage ’walk-cycle-ride’ modes of transport to make the transportation system car-lite; and third, in the hot and humid weather of Singapore, powered micromobility devices are a convenient mode of transport not requiring much physical exertion by the rider, in addition to the population being technology-friendly. This makes the case novel and prominently discussed in the literature related to micromobility, fulfilling the case selection criteria by [25]. The Land Transport Master Plan advisory panel (LTMP) proposed in 2019 emphasised the goal of Singapore to become a 45-min city by 2040, which translates to 90 per cent of the peak-hour trips by foot, cycle, or shared transport to be no more than 45 min [26]. Since PMDs would play a crucial role in achieving this goal, the LTA focused on creating a regulatory framework for the safe use of active mobility devices [27].

3. Case Description: Personal Mobility Devices in Singapore

In this section, we elaborate on the phases in governing powered micromobility devices in Singapore. A more detailed description of the case and different phases are provided in supplementary material B [28,29,30,31,32,33,34].

3.1. Phase 1: Recognising the Importance of PMDs and Setting the Agenda for Active Mobility

The initiative towards promoting micromobility in Singapore kickstarted in 2013 when the LTA masterplan discussed the importance of the first-mile and last-mile connectivity [35]. The Transport Ministry in Singapore made ‘car-lite Singapore by 2030’ a major theme and even launched the ‘Walk, Ride, Cycle’ campaign to encourage commuters to take public transport rather than driving cars in the Sustainable Singapore blueprint [36]. Adopting PMDs comprising electric scooters, hoverboards and unicycles as modes of transport became a major catalyst for this change.

An Active Mobility Advisory Panel (AMAP) was set up in March 2015 to identify rules for using footpaths, shared paths and cycling paths by users of active mobility devices. The AMAP comprises different stakeholder representatives of youngsters, seniors, and users of those devices. The aim was to determine rules to ensure safety while meeting the requirements of mobility device users and pedestrians. The panel suggested the first set of rules for the devices in a report published in March 2016 [37]. The proposed rules recommended a criterion of maximum weight (20 kg), width (700 mm), motorised device speed (25 km/h), a code of conduct for PMD and PMA users, and speed limits of 15 km/h on footpaths and 25 km/h on shared and cycling paths. In addition, motorised bicycles that could be modified had been recommended to be registered. All recommendations were accepted by the government to be put forward in the parliament for debate.

Till the AMAP published their report in March 2016, there were no clear regulations for PMDs, and there was no clear differentiation between different types of PMDs including bicycles. In September 2016, the accident of a woman who suffered severe brain injury involving a teenager riding an e-scooter raised concerns about the safety of PMDs, especially e-scooters [38]. A Safe Riders Campaign and Safe Cycling Programme for educating cyclists and PMD users about the code of conduct, rules and penalties were also planned to improve awareness efforts. To enforce rules on speed limits, an active mobility enforcement officers’ team to advise cyclists and PMD users were established by LTA. There were also active mobility patrol teams comprising of volunteers to spread information about safe riding and rules. To promote public transport usage, a six-month trial was undertaken in November 2016 under allowing commuters to carry their PMDs on buses or trains provisional on the size standards [39].

3.2. Phase 2: Introduction of Active Mobility Bill (2017), E-Scooter Sharing Services, and Increased Surveillance

In Singapore, the Active Mobility Bill was passed in Parliament in January 2017 and became the Active Mobility Act on 20th June 2017 [40]. This Act legitimised the use of PMDs with rules and codes of conduct [41]. It comprises issues related to the declaration of public paths, sharing public paths, and the sale of PMDs. To enforce rules related to PMDs, the Act authorised an active mobility patrolling scheme with authorised officers, public path wardens, and volunteers [42]. The regulations disallowed power-assisted bicycles on footpaths and banned e-scooters on public roads. As the regulations were being enforced, there were various stumbling blocks with the growing popularity of PMDs. The pathways were likely to get crowded, and there had been an increase in cases of speeding and reckless driving of PMDs [43]. To improve safety measures, recommendations were made to use helmets by users of PMDs, introduce third party liability, and use speeding guns and setting up CCTV cameras in high-risk locations (ibid.). The government also announced the compulsory registration of e-bikes with LTA and a requirement of a number plate on the bikes. The fine for offences related to PMDs was SGD 100 for a first-time offence irrespective of the road the device is driven on, SGD 200 for a second offence and SGD 500 for the third and subsequent offences [44].

The e-scooter sharing services started in Singapore in June 2017 when Telepod, a local start-up started operations in the Suntec area. Following this, companies based in and out of Singapore, such as Neuron Mobility, Floatility, and PopScoot began introducing e-scooter sharing services in heartlands and downtown areas. Meanwhile, steps were taken to make the residential area of Ang Mo Kio (AMK) the first walking and cycling town in Singapore by building infrastructure for cyclists and pedestrians reach to a mass rapid transport (MRT) station, swimming pool and AMK hub [45]. While there were developments in the adoption and use of e-bicycles and PMDs, the number of accidents leading to injuries increased. The LTA began registration of e-bicycles in August 2017 with a deadline of 31st January 2018 beyond which fines or jail were to be imposed. The e-bikes were required to undergo an inspection, possess a seal of the LTA, and a number plate. The figures for accidents involving e-bikes increased from 39 to 54 between 2015–16 [46]. No separate accident statistics for PMDs were reported until the end of 2017. There was also a difference in the regulations for e-bicycles and PMDs. E-bicycles required an approval from LTA, while this was not required for PMDs [37].

In the later months of 2017, the cases of speeding, illegal modifications of PMDs, and fire accidents from the battery of e-scooters also increased. To deal with the fire incidents, the Singapore Civil Defence Force (SCDF) communicated warnings on social media (Facebook page). The advisory issued included guidelines on charging batteries and cautioning users about placing PMDs away from combustible materials to avoid fire accidents (details about guidelines in supplementary material B, Phase 2, paragraph 5). The testing and certification requirements for PMDs were also reviewed by SPRING Singapore and LTA in an inspection when six e-scooter suppliers were found to be selling unregistered charging adaptors and illegally modified PMDs that were seized [47]. SPRING Singapore was the Standards, Productivity and Innovation Board, the standards setting statutory board under the Ministry of Trade and industry in Singapore. It merged with IE Singapore in April 2018 and became Enterprise Singapore.

3.3. Phase 3: Recurring Policy Evaluation and More Regulations for Active Mobility Devices

By the start of 2018, the rise in accidents and offences involving PMDs became a cause for concern for the LTA. The issue of applying rules to the various types of PMDs also became a matter of contention. Due to the conflation of types of micromobility devices, there was a lack of distinction of rules between PMDs, e-bicycles and PMAs. The lack of necessary infrastructure for PMDs with some narrow walkways, broken stretches of paths or blocked by trees or lamp posts, and dimly-lit paths was also recognised [18]. In the majority of the areas, such as Yishun and Ang Mo Kio, the users were abiding by the rules; however, in Geylang PMD users were flouting rules that increased the risk of accidents [48]. Accidents involving PMDs averaged 3 in a week between January-September 2017 [49]. The idea of power-assisted PMDs to be registered and provision of third-party insurance was introduced when the Transport Minister provided an update on the accidents between PMD users and pedestrians [50]. This led to a slew of regulations imposed on PMDs for safety.

From 15th January 2018, the LTA increased the fines for offences related to the use of PMDs by three times—SGD 300 for a first-time offence on a local road and SGD 500 on a major road; driving on expressways was to be charged in court with a maximum penalty of SGD 2000 and jail for 3 months [51]. To create more awareness about safe riding, LTA started a Safe Riding Programme in schools, community clubs and foreign worker dormitories involving a 90-min theory and practical lesson and information campaigns comprising banners on lamp posts to create awareness on safety aspects while riding PMDs were also undertaken [52]. The food delivery riders of companies such as Grab Food, Foodpanda, and Deliveroo also formed a key segment of PMD users and in anticipation of the increase in the frequency of deliveries during the festive season in Chinese New Year, the Workplace Safety and Health Council published a guide on safe riding for food delivery riders outlining provision of storage spaces in PMDs for ease of carrying packages, training on safe riding behaviour for riders [53]. In February 2018, AMAP proposed mandatory registration of e-scooters (excluding hoverboards and electric unicycles), and the LTA accepted it with the hope to discourage reckless riding, provide more responsibility to the users, and help enforcement officers in tracking down the reckless users [54].

3.4. Phase 4: Enforcement of Active Mobility Act, Stricter Regulations, and Introduction of Land Transport (Enforcement Measures) Bill 2018

With the enforcement of AMA on 1st May 2018, the users of PMDs had to adhere to all the regulations (highlights of the Act are presented in Table 2). The LTA provided speed guns to enforcement officers to catch reckless users of PMDs [55] and auxiliary police officers from Certis Cisco were employed for enforcement of rules [56].

Table 2.

Highlights of the Active Mobility Act [41].

By this time, there was a growing sentiment of PMDs being risky and demanding a ban due to the increase in hit and run and collision cases involving PMDs [57]. In addition, pedestrians were negatively affected by the PMDs. On 15th May 2018, in the parliament, MP Dennis Tan recommended lowering the speed limit for PMDs from 25 km/h to 15 km/h along with educating road users on safety. A fire accident due to the battery explosion of a PMD that injured two boys and the 16 other cases from January to April 2018 brought to light the existing dangers of bad batteries in PMDs [58]. As the size specifications of PMDs were outlined in the AMA, there were also concerns from the disabled community that used PMAs about the application of strict rules for PMDs on PMAs, since some retailers started marketing PMDs with seats as PMAs [59].

In a nationwide sting operation conducted on 18 retailers from 17th July to 2nd August 2018 by LTA, it was found that five retailers were advertising or displaying non-compliant PMDs and five retailers had not displayed LTA’s warning notice on technical criteria for the various PMDs and PABs [60] (See supplementary material C Figure S2 for the warning notice). The AMAP submitted another set of recommendations to regulate PMDs on 24th August 2018. These focused on preventing accidents and improving safety by lowering the speed limits for PMDs on footpaths to 10 km/h, the mandatory wearing of helmets and practice of "stop and look for traffic" at road crossings by the users of active mobility devices [61]. Since the disambiguation of rules for PMDs and PMAs was a concern, a maximum device speed of 10 km/h was recommended by the AMAP. Voluntary provision of insurance by employers for active mobility devices was allowed and the panel encouraged users to get insurance, but it was not recommended to make it mandatory. All the recommendations were accepted by the Ministry of Transport to be imposed from 1st February 2019 [62].

In September 2018, due to the increasing incidence of accidents, the Land Transport (Enforcement Measures) Bill was passed in the parliament to enforce tougher regulations on active mobility devices [63]. The Bill covered all major concerns listed in the proposals to regulate active mobility devices (ibid.). These included mandatory registration of e-scooters (recreation of markings on e-scooter in supplementary material C Figure S3), a rebuttal presumption rules for offences related to active mobility devices, clarifying regulations for PMAs, the introduction of the UL2272 standard for PMDs and employing outsourced enforcement officers (details about the bill in supplementary material B, Phase 4, paragraph 5).

3.5. Phase 5: Regulations for E-Scooter Sharing Companies and Steps Taken to Ensure the Safety of PMDs

By 2018, many e-scooter sharing service providers had started to show interest in operating in Singapore. Before this, the e-scooter sharing companies were allowed to operate only in areas via an agreement with the private townships. On 23rd October 2018, LTA made a statement for interested device-sharing companies about the requirement of a license for operation, and fines for unlicensed operators up to SGD 10,000 and jail up to six months with SGD 500 for every additional day of operation [64]. During this time, 42 shared e-scooters were confiscated after the companies Neuron Mobility, Telepod, and Beam were found to have been operating without license or exemption, despite the repeated reminders and warnings between July–October 2018 [65]. Telepod and Neuron Mobility had been allowed to operate only in specific locations without a license, based on an agreement with the landowners. LTA also clarified that they would allow only small-scale operations (with a limited fleet of PMDs) for PMD sharing operators through an application process for ‘sandbox licenses’. Fourteen companies applied for the sandbox license to operate a minimum of 200 devices and a maximum of 500 in the application cycle ending 11th February 2019 [66]. The companies were Lime, Bird, Beam Mobility, Telepod, Anywheel, Gogreen, Grab Wheel, Helbiz, Moov mobility, Mover Scoot, Omni Sharing, SG Scoot, Smart World Telecommunications and Mobike. However, during the waiting period for approval, LTA confiscated PMDs of companies operating without licenses, warning the applicants of the need for compliance and consideration of track record in evaluating applications (details about the application process in supplementary material B, Phase 5).

To catch reckless riders, LTA introduced CCTVs at hot spots and a feature on the MyTransport.SG app whereby users could send pictures or videos and report irresponsible riding of PMDs in June 2019 [67]. By 24th September 2019, 270 reports had been filed by members of the public on reckless riders of PMDs [68]. With 31st June 2019 as the deadline for registration of e-scooters, LTA received more than 85,000 registrations for e-scooters with most registrants between ages 21 and 50 [23]. By the second half of 2019, the operation of PMDs had become a controversial topic due to safety concerns. There were major announcements made in the ministerial statement in the parliament on 5th August 2019 [69]. The deadline for compliance with UL2272 and disposal of non-compliant devices was advanced by six months, and inspecting PMDs for compliance and certification was made mandatory [70]. The decision to invest SGD 50 million in building path infrastructure for PMDs was also taken. Fifteen town councils banned PMDs on void decks and common places at HDB blocks. Void decks in Singapore refer to the ground floor of the housing development board (HDB) blocks. These are made as sheltered blocks where people can meet or get together. Trials for dismounting and pushing PMDs in ‘pedestrian free zones’ and markings to slow down were also undertaken to ensure safety. A government task force comprising of the Singapore Civil Defence (SCDF), LTA, the Housing Board, and Enterprise Singapore was established in August 2019 to manage concerns of fire accidents [71].

3.6. Phase 6: Increasing Safety Concerns, Ban on E-Scooters, and Amendments in the Active Mobility Act

LTA delayed the issue of sandbox licenses further to consider more requirements on the 12 applicants to ensure the general public’s safety [72]. Despite the attempts to control the reckless operation of PMDs, the sudden increase in offences related to active mobility devices from 595 in July 2019 to 761 in August 2019 was concerning [73]. The death of a 65-year-old cyclist due to a collision with a non-compliant PMD (exceeding the weight and width restrictions) on 21st September 2019 further attracted attention to the risks in the operation of PMDs in Singapore. In a review of regulations for active mobility devices, the AMAP submitted their recommendations on 27th September 2019 for mandatory third-party liability for businesses, the minimum age requirement of 16 years, a mandatory test for e-scooter users, and code of conduct for pedestrians (details of regulations in supplementary material B, Phase 6). The government undertook a review after petitions from citizen groups and victims to ban PMDs from footpaths [74], and a statement by a Senior Minister of State for Transport on the need to improve the behaviour of PMD users to avoid a ban. In response to the increasing accidents involving PMDs, a group of twenty-seven retailers pledged to follow measures for enhancing PMD safety by restricting sale to underage users and sell devices compliant with the rules of registration [75].

The LTA finally banned e-scooters from all footpaths (except cycling paths and park connector networks) from 5th November 2019 [76]. An advisory period was slated till 31st December 2019, after which heavy penalties of SGD 2000 and/or 3 months of imprisonment was decided. The LTA also rejected existing license applications of e-scooter sharing companies and prohibited any applications in the future. The ban had heavily hit the food delivery riders who relied on PMDs, and retailers of e-scooters in Singapore. Groups of food delivery riders lobbied for reviewing the ban on PMDs and shared their grievances due to loss of livelihoods at various ‘Meet-the-people’ sessions organised by the government [77]. The government introduced a ‘transition assistance package’ by providing an SGD 7 million grant, called the e-scooter Trade-in grant (eTG), to replace e-scooters with SGD 1000 to buy an e-bike or SGD 600 to purchase a bicycle for approximately 7000 riders [78]. This grant was funded equally by the government and the three food delivery companies—GrabFood, Foodpanda and Deliveroo. In addition, the government also provided the option to switch jobs via the Employment and Employability Institute (e2i) and Workforce Singapore (WSG) (ibid.).

In February 2020, a bill for amending the Active Mobility Act was introduced, focusing on PMDs and the use of public paths (see Table 3 for the details of the regulations). This bill introduced more stringent regulations, with the main ones being the ban of PMDs on footpaths, the requirement of a competency certificate by users, disallowing use of mobile phones while riding, and mandatory third-party insurance by businesses for employees (see supplementary material B Phase 6 for the details of the bill).

Table 3.

Additions in the amended Active Mobility Act [79].

The Shared Mobility Enterprises (Control and Licensing) Bill was also passed on 4th February 2020 impacting licensing regulations for business operators offering docked motorised PMDs and PABs for hire in public places from April 2021 [30]. This prescribed two types of licenses for device-sharing business operators—‘regular’ licenses for dockless motorised and non-motorised devices, and ‘class’ licenses for docked motorised device sharing firms [80].

In May 2020, the small motorised vehicles (safety) bill and another amendment to the AMA was introduced in the parliament. The main motivation was to require all importers to obtain approval to import PMDs from LTA, restrict imports of illegally modified PMDs, and allow LTA to quickly forfeit any non-compliant micromobility device [81]. The path-connected open spaces were also included as public paths to clarify the connotation of public paths. The AMAP submitted another set of recommendations in December 2020 emphasizing the need for third-party liability insurance for commercial users and suggested monitoring the feasibility before making it mandatory for non-commercial users [82].

4. Case Analysis and Insights about Governing Strategies

While powered PMDs have several benefits for providing access to those with no or reduced mobility, those who need to shuttle between places at close distances or who need an additional form of transportation [83], challenges for their adoption remain for governments all over. Based on the case description and literature, we identify four major risks of adopting PMDs in Singapore. Using the insights from the case description, we further look into the governing strategies undertaken by the government during the period of analysis.

4.1. Risks of Powered Micromobility Devices

In the literature discussing risks of powered micromobility devices, safety has been cited as the foremost concern [13,14,79]. When e-scooter sharing companies collect data of the users, privacy risks are also one of the technological risks [84]. One of the major concerns after the ban on e-scooters was the outcry from the food delivery riders due to the risk of switching transportation mode. In this study, we focus on the safety risks, liability risks, privacy and cybersecurity risks, and the risk of switching transportation mode (explanations in Table 4) in adopting PMDs in Singapore.

Table 4.

Explanation of risks of powered PMDs in Singapore.

4.1.1. Safety

Safety risks would comprise of risks from accidents and the consequent injuries. The severity of the injury depends on the speed of the device and the resulting kinetic energy [85]. A small increase in speed increases the kinetic energy by a large amount, which greatly impacts the severity of the injury. There was a consistent increase in the number of accidents involving bicycles, PMDs, and PABs on public paths in Singapore (Table 5). Healthcare is an invisible cost associated with injuries involving PMDs. Patients with no protective gear had to incur higher median cost in case of PMD-related accidents in Singapore [86]. In a cohort study in Singapore, motorised PMDs triple the risk of severe injuries as compared to non-motorised PMDs due to the high travelling speeds [87]. Emergency departments of hospitals in Singapore had started seeing more injuries related to PMDs [88]. The incidence of e-scooter related injuries increased 2.3 times from 11 to 16 between 2015 and 2016, with 38.9 per cent of the injuries caused by the riders and 30.6 per cent involving another party [89]. Despite the imposition of AMA in 2017, the incidence of accidents due to PMDs and the severity of injuries increased substantially in Khoo Teck Puat Hospital between November 2014 and October 2017 [83]. Statistics of PMD riders with accidents admitted to public hospitals with serious injuries increased from 10 in 2017 to 23 in 2018 [90]. Even the pedestrians had grievances about the reckless riding of PMDs. In the AXA Mobility survey in 2018, 77 per cent of people surveyed in Singapore reported feeling more congestion in footpaths, and 72 per cent thought that bikes and PMDs contribute to more accidents [91].

Table 5.

Accidents involving bicycles, PMDs, and PABs on public paths [61].

Another safety risk was fire accidents involving PMDs. A major reason cited for the increase in fire accidents involving PMDs was the use of cheap-unbranded batteries that cannot handle the heat and were left to overcharge; these were available on e-commerce platforms such as Carousell and Taobao [92]. For safety assurance, users were encouraged to purchase the devices from approved sources and ensure adaptors have the Spring Singapore’s Safety Mark (ibid.). The number of fire accidents related to PMDs and PABs showed a substantial increase every year from 2015 to 2019 (details in Table 6). While there was a significant decrease in fire accidents involving PMDs in 2020, the number of fire accidents involving e-bicycles had doubled to 26 [93].

Table 6.

Fire accidents related to PMDs and PABs [94,95].

4.1.2. Liability

Clarifying the assignment of responsibility in the event of an accident has been a major concern in the case of powered micromobility devices [96]. Liability concerns in the case of operation of PMDs can be thought of in two areas—product liability and insurance coverage. Product liability refers to the liability of the manufacturer to the consumer or third party when they suffer harm due to the product [15]. An aggrieved party imposes product liability due to negligence, warranty, or strict liability (ibid.). A strict liability law would assign the responsibility on the manufacturer for any injury to the user regardless of negligence, for instance, when the e-scooter companies Lime and Bird were held responsible due to manufacturing or design defects in the United States [97]. To overcome liability concerns, some companies like Bird sign an agreement with users to ensure the following: “By choosing to ride a vehicle, rider assumes all responsibilities and risks for any injuries or medical conditions” [98]. This makes the user apply only for arbitration and not a court case in case of an accident. The requirement of a third-part insurance provision by the company clears few liability issues, which was made mandatory by the LTA for food delivery companies for their riders but was not enforced for private users of powered micromobility devices.

4.1.3. Privacy and Cybersecurity

There is evidence of e-scooter sharing companies collecting data from and of the users. The service providers collect details such as contact information, billing information, identification information and demographic information from the users; device information, location information and analytics are automatically collected; and user interactions related to the company are provided by third-party sources [99]. With powered micromobility device-sharing, the risk of cybersecurity is also conceivable. The applications used to access the micromobility devices can track the location of the devices or through the smartphone of the users [99]. Spoofing or the act of disguising information from the original source is possible in two ways (ibid.). First, the attacker or user can disguise the location by downloading and location-faking applications to deceive the application and second, the GPS signal can be manipulated using software-defined radio that can make and forge GPS signals. While this was not possible because licenses were not granted to e-scooter sharing companies in Singapore, privacy would not be a serious concern due to the Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) [100]. The PDPA is a key data protection legislation to protect the privacy of citizens. Businesses in Singapore are under an obligation to use personal data responsibly—they need to obtain consent for using the data of individuals and inform them if that is being used.

4.1.4. Risk in Switching Transportation Mode

Since there are various forms and types of powered micromobility devices, it may lead to unintended consequences for the people who depend on a certain device for their livelihood. The ban on e-scooters had employment and labour related implications for the 7000 food delivery riders in Singapore. The food delivery riders were anxious about the decision since they used e-scooters extensively for food delivery, and the switch to bicycles was inconvenient to not only undertake but also harmful to use for long periods (especially for those with health problems) [101]. This disruption caused much commotion amongst this group of stakeholders, following which the government introduced an SGD 7 million e-scooter trade-in grant with alternative job options to assist them. The LTA received 3500 applications, out of which 74.6 per cent of applicants applied for power-assisted bicycles, 24.8 per cent for bicycles, and 0.6 per cent for personal mobility aids [102]. As an interim alternative, the food delivery companies provided the riders with free bicycle rentals (ibid.). This indicates the means through which the government tried to manage the risks arising out of the switch to other micromobility means for people who depended on e-scooters for their livelihoods.

4.2. Governance Strategies in the Adoption of Powered Micromobility Devices in Singapore

To manage risks from adopting powered micromobility devices, the Singapore government followed a combination of governing strategies. Six governing strategies can be responses to deal with risks (explanations in Table 7): no-response strategy, precaution-oriented strategy, prevention-oriented strategy, control-oriented strategy, toleration-oriented strategy, and adaptation oriented strategy [16].

Table 7.

Governance strategies as responses for coping with risks.

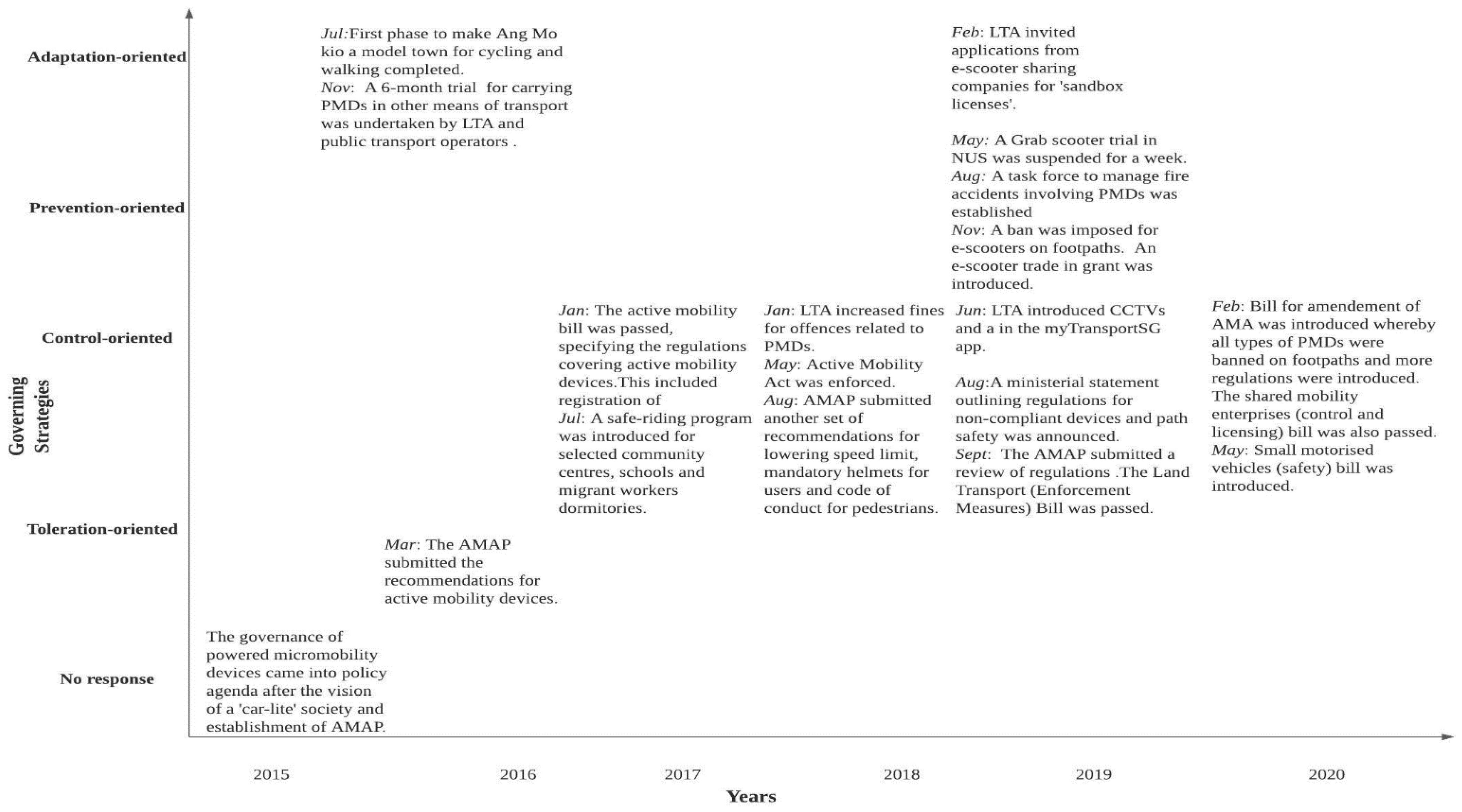

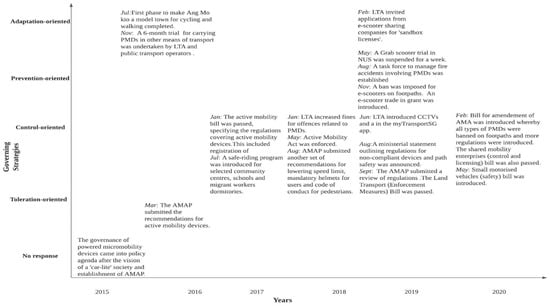

The government adopted different policy measures to regulate the use of powered micromobility devices based on the safety risks, liability risks, and the risk of switching to a new transportation mode. Following [16], we present the various governing strategies of the government towards micromobility devices using the case information with the governing strategies overtime mapped out in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Governing strategies and timeline of regulations for powered micromobility devices in Singapore.

4.2.1. No Response Strategy

Before 2014, the Singapore government did not have any definitive policy for active mobility devices. It was only in 2014 with the vision of a ‘car-lite’ Singapore, and in March 2015, after the establishment of AMAP, the operation of active mobility devices was scrutinised. Thus, until 2014, the government in Singapore adopted a no response strategy towards powered micromobility devices.

4.2.2. Toleration-Oriented Strategy

With the establishment and acceptance of initial recommendations of the AMAP in 2016, the government started following a toleration-oriented strategy to ensure that only powered PMDs that fulfil a specific criterion are adopted by the users.

4.2.3. Control-Oriented Strategy

With the increase in road and fire accidents involving PMDs, the government in Singapore adopted control-oriented strategies beginning in 2017. This has been the most dominating strategy in regulating PMDs. Based on the recommendations of AMAP, which brought together different stakeholders involved in micromobility usage for their suggestions, the government started imposing regulations. An insight into the summary of recommendations by AMAP (that were eventually accepted by the LTA) through the years indicates the increasing control of the government to arrest the problem of safety (details in Table 8). Initially, they followed light-control oriented strategies. The control tightened over time, with an increase in penalties and regulations (details in Figure 1).

Table 8.

Summary of AMAP recommendations [41,56,102].

The AMA passed in 2017 laid the foundation for imposing regulations on micromobility devices. From July 2018 onwards the government became particularly alert and investigative when a sting operation on retailers took place to recognise if PMDs compliant with the government regulations were being sold. The ministerial statement in August 2019 was indicative of a heavy control-oriented governing strategy when various regulations related to mandatory registration of e-scooters, assigning responsibility in the event of accidents, application of the UL2272 standards and expansion of the team of enforcement officers were announced. This made the regulatory landscape for powered micromobility devices in Singapore more robust and tight control-oriented.

LTA took a cautious approach by taking time to go through the applications for giving sandbox licenses to companies. However, while the government acknowledged the benefits of using PMDs to the users and even the responsible use by the majority of the users, the risks arising from their use outweighed the benefits. By August 2019, there were ideas of banning the use of PMDs; however, the Minister of State for transport assured that enough measures were being imposed, such as mandatory inspections of UL2272 compliant devices, making enforcement more robust and higher penalties for reckless riders or incompliant retailers [105]. The ban on the PMDs on footpaths and public paths was imposed after an amendment to the AMA in February 2020 with more control over service providers through the shared mobility enterprises (control and licensing) bill. The control-oriented strategy of the government is also exhibited in the introduction of the small motorised (safety) bill in May 2020 to regulate the import of active mobility devices.

4.2.4. Prevention-Oriented Strategy

Due to the recurring accidents involving pedestrians and PMD users and fire accidents due to overcharging of PMD batteries, the government started implementing prevention-oriented strategies when they established a task force to investigate and manage the increasing fire accidents involving PMDs in August 2019. Next came the ban on the use of e-scooters on footpaths in November 2019. This led to another set of challenges for the government since it affected the livelihoods of the food delivery riders. To manage this, the government helped them through a monetary package to switch to e-bikes and counselling for alternative jobs. Finally, LTA announced a ban on all types of PMDs on footpaths in February 2020. These strategies to govern the risks arising from the use of PMDs were undertaken after discussion and deliberation by policymakers because despite using various policy instruments through control-oriented governing strategies, the safety of pedestrians and PMD users were still in jeopardy.

4.2.5. Adaptation-Oriented Strategy

Through a vision of making Singapore car-lite, the government undertook the adaptation-oriented strategy in several ways to develop the capacity for safe adoption of powered micromobility devices. The decision to experiment with the AMK hub a walking and cycling town, by providing requisite infrastructure (cycling paths) and continuing to expand the cycling network is an example of that. The government also introduced policy pilots like the 6-month trial for carrying PMDs in public transport. The regulation of ‘sandbox licensing’ for micromobility service providers also indicates the intention of the government to deal with policy uncertainty.

5. Discussion

The case of the regulation of powered micromobility devices in Singapore brings various insights about the dilemmas faced in the governance of new transportation technologies and the approaches to manage them. The case description of the adoption of devices in Singapore introduces the policy process of regulating a novel technology and the impact of new forms of transport on policymaking, especially policy formulation and implementation. Our analysis through the case study reveals that the government initially took time to ’wait and watch’ while adopting light control and then turning to heavy control governing strategy before finally banning the use of PMDs on public paths. Since the idea of defining micromobility devices is still evolving, the government kept re-working the ambiguities in classifying the devices as well (for instance clarifying the size and weight dimensions for the operation of PMDs and PMAs). The majority of the regulations were focused on e-scooters due to their widespread use in the city-state and the accidents involving them. The case study suggests that a combination of governing strategies and an adaptation-oriented strategy would be relevant to deal with the diverse risks of adopting this new transportation technology. Singapore was able to adopt this stance through policy learning and drawing lessons.

The safety concerns were key in driving the decisions about control-oriented governing strategy. The establishment of the AMAP provided a platform for the stakeholders to express their viewpoints about powered PMDs and assisted the government in framing regulations. With every round of reports submitted by the AMAP, there were more regulations introduced. Some major changes in legislation occurred between 2018 and 2019 when there was a focus on rules not only for the PMD users but also for pedestrians by introducing a code of conduct. The introduction of mandatory registration of e-scooters was to ensure ownership of the devices and the availability of information of the user in case of accidents. In addition, to tackle fire accidents, the UL2272 standard was introduced, and later the government also established a task force comprising of a collaboration of different agencies to control fire-related incidents. The turning point in the case of governing the devices in Singapore was the death of a woman hit by an e-scooter rider in September 2019. There had been 6 deaths recorded involving PMD riders and pedestrians between January 2017 and September 2019 [106]. Eventually, this led to a ban on e-scooters on footpaths, which was later extended to all PMDs with the amendments in the AMA in 2020.

With the safety of users and pedestrians being of prime importance, the government also sought to nudge the stakeholders to make behavioural changes and adapt to the adoption of powered micromobility devices. The use of campaigns, programs for safe riding, code of conduct for pedestrians and employment of enforcement officers were key steps taken. While safety issues were addressed to a great extent, the liability risks were not completely addressed. There was a move from no regulation on insurance to optional third-party insurance provided by businesses for their employees and further making this mandatory. However, for individual PMD users, there was no legislation notified on buying insurance though there were proposals to purchase third party insurance mandatory [107]. Insurance-related to micromobility devices is complicated due to the ambiguity in coverage. The coverage would not be clear if an accident occurs involving an e-scooter user resulting in an injury to a pedestrian or damage of private property [108]. Perhaps the issue of liability would become important when e-scooter sharing companies start to operate in Singapore. The Shared Mobility Enterprises (Control and Licensing) Bill was introduced to cater for licensing of micromobility sharing businesses in April 2021. While it does seem that the government is not opposed to the idea of revisiting regulations and continuing operations of powered micromobility devices, the liability issues need to be clarified beforehand. Unlike in other contexts where privacy risks of e-scooters were cited when e-scooter sharing companies collected data of the users who hired the devices, this was not a cause of concern in Singapore.

The lack of proper infrastructure for active mobility devices, including powered micromobility devices has also been a cause for concern in Singapore [109]. Initially, PMDs were allowed on roads when the government followed a no-response strategy. However, after they were allowed only on footpaths, the incidence of accidents and congestion on footpaths increased. As part of the ’car-lite’ vision in Singapore, cycling networks have been proposed and micromobility devices would be allowed on those; however, there has been no talk about exclusive paths for powered micromobility devices. With the development of a future mobility innovation research centre in Singapore by Hyundai and the introduction of a prototype of a foldable e-scooter that can be carried in the trunk of a car for last-mile transportation, there is wide scope for adoption of e-scooters [110].

The case also brings to light the diverse stakeholders in the adoption of powered micromobility devices. This is important to consider the varied incentives, benefits, and drawbacks of specific policy regulations implemented. The dependence of food delivery riders on powered micromobility devices and their concerns after the ban on e-scooters was one of the major risks in the case of Singapore. With the uproar due to the concerns of the stakeholders, the government conducted meetings with them to listen to the concerns. The grant for a switch to e-bikes and the help extended for alternative jobs due to loss of employment was a key prevention-oriented governing strategy. However, the retailers’ concerns remained due to the unsold stock of the devices after the sudden ban announced by the government. To streamline the variety of devices that would be allowed in Singapore, the government has introduced a regulation to control the imports of powered micromobility devices. Introduced as a result of policy learning, this will help to nip the problem in the bud by having only compliant devices in the market. However, this does leave room for modifications on the devices to be done in Singapore and importing parts of mobility devices for assembly.

Minimising hurt, injury or loss of human life is a key principle of government policies [111]. Given the uncertainties and safety risks, the LTA imposed a ban on PMDs from roads and footpaths after carefully monitoring the consequences of the regulations. This prevention-oriented strategy indicates the risk avoidance stance of the government to prohibit new technology and the associated risks [16]. While such a governing strategy would prevent capitalising on the benefits of powered micromobility devices, a phased deployment while ensuring safety would enable the adoption of the devices. The next section lists actionable policy recommendations.

6. Policy Recommendations for Adoption of Electric Micromobility Devices

6.1. Strengthening Infrastructure and Policy Capacity for the Adoption of Powered Micromobility Devices

The physical foundations for powered micromobility devices like dedicated paths with proper lights and roads will support easier adoption. The limited infrastructure for such devices is one of the key challenges in their use. In the realm of transport planning, while infrastructure provision is key to meet future transport demand, the availability of opportunities and evaluation of environmental and social concerns is also important [112]. Dedicated lanes for micromobility devices with sufficient lights, ample and proper parking spaces to reduce indiscriminate parking are the major components of physical infrastructure [5,113].

While shared mobility services were limited in Singapore, the future regulations in case of the continuation would benefit from planning for parking. The parking of e-scooters on sidewalks would require space management so that they can be properly parked by standing upright and not blocking pedestrian paths, and policies on scooter parking in private properties akin to requirements of space for bicycle parking in those properties should be encouraged [114]. The first and last mile access is one of the key motivations for using these devices, and hence integration with the public transport system is a relevant issue [3]. The needs of a user with a privately owned micromobility device would be safe and affordable storage with convenience in reaching the platform for the onward journey, while for a shared device would be the availability of free space for parking/docks and proximity of the parking to the platform (ibid.).

Quite a few risks of powered micromobility devices remain unknown. However, the case of Singapore has been insightful to bring into the picture the immediate and major risks that would help anticipate other risks and use the appropriate governing strategies to address them. Adopting powered micromobility devices widely would require a high degree of policy capacity as with any new technology [115]. In the case of Singapore, the high degree of policy capacity is evident in the proven track record of economic growth and development, and policy implementation for novel technologies like autonomous vehicles [84]. While the case study highlights the regulatory capacity in terms of the use of varied policy instruments for safety in powered micromobility devices, there is a need for a clear liability regime, especially when e-scooter providers are allowed to operate in Singapore.

6.2. Inclusive Participatory Policymaking for Micromobility Devices

The adoption of powered micromobility devices affects various segments of society. In the case of Singapore, the dynamics between different actors and the role of the government in balancing diverse incentives was key in governing the devices. Our case study shows that the government alone might not be able to anticipate risks or manage them, and would need other stakeholders like the retailer community, key users of the micromobility devices, and powered micromobility device providers. While participatory policymaking is evident in the case through AMAP comprising of a diverse stakeholder community, there is a need for continued ’inclusive’ participatory policymaking for the devices. The AMAP includes stakeholders from various walks of life like transport governance, occupational therapy, cycling enthusiasts, youth council, advocate for pedestrians, and online community of cyclists. Including retailers and representatives from PMD-sharing service providers would lead to greater inclusiveness in citizen participation.

The process of citizen participation in decision-making is beneficial due to the convenience in the collection of information of the position of various community groups and smoother and more cost-effective policy implementation with increased cooperation of the public [116]. Citizens can be included in policymaking through public consultations, dialogues, crowdsourcing and even participation in research studies [32,117]. A high degree of citizen engagement in policy decisions can also improve behavioural policy [118]. This would help in the behavioural change for the safe adoption of powered micromobility devices, which was a key concern of the government.

6.3. Government Stewardship to Resolve Short-Term and Long-Term Implications of Powered Micromobility Devices

The case of Singapore provides an insight into the multiplicity of actors involved in issues surrounding powered micromobility devices and ensuing complexities in regulating emerging transport technologies. To regulate emerging technologies, government stewardship is required to understand the concerns of all stakeholders and address risks. The ramifications of the ban of PMDs on footpaths and public paths on the food delivery riders and the ensuing transition package to resolve the problem attests to the important role of the government. To address safety risks, the Singapore government also introduced sandbox licenses for powered micromobility service providers that ensures flexibility and adaptability in regulations to manage any risks or challenges. Continuation of pilots and trials to encourage the use of powered micromobility devices would ensure safety and a higher level of deployment for capitalising on their benefits. The government can determine appropriate locations for pilots and trials with suitable infrastructure to strengthen the readiness for adopting the devices and identify the resources required for full deployment. By correctly recognising the incentives and needs of stakeholders, governments from other countries can draw on the experience with problems and solutions advanced in Singapore. With the spirit of regular consultation and seeking feedback from the public, the government could balance the risks from adopting the devices and the benefits to the stakeholders.

6.4. The Simultaneous Adoption of Different Governance Strategies Overtime to Manage the Risks of Adoption of Powered Micromobility Devices

The pacing problem, defined as the situation of innovation outpacing the existing regulations to manage the consequences [119] has been a key concern in regulating novel technologies. The Singapore case elucidates the use of a combination of governing strategies overtime to manage safety, liability and switching transport mode risks. The government used the conventional approach through a control-oriented strategy by using policy instruments to regulate the risks arising from the use of e-scooters. This was evident by the imposition of speed limits, condition for compliant devices allowed to be used, and the various penalties for offences. Over time the toleration-oriented and adaptation-oriented strategies were used to anticipate risks and prepare for the new technology and build robust structures and increase the government’s capacity in dealing with policy uncertainty. Infrastructure for e-scooters and active mobility devices and safe riding programs were developed. As a result of the increased number of accidents and to avoid risks, the government used a prevention-oriented strategy by introducing a ban on e-scooters and other devices on public paths and footpaths. A combination of strategies, especially along with adaptation-oriented governing strategy indicates a very involved and prescriptive approach with the scope to review and amend policies [32].

7. Conclusions

The in-depth case study of Singapore presents the potential risks and dangers of adopting powered micromobility devices. We find that the government managed the major risks of safety, liability, privacy and cybersecurity, and the risk of switching to a new transportation mode. They adopted five strategies—no response, control-oriented, prevention-oriented, toleration-oriented, and adaptation-oriented, sometimes even combining strategies to manage the risks. The insights from the evolving risks and lessons from governing strategies in Singapore could guide other countries in adopting powered micromobility devices.

Singapore has executed the governing strategies in a cautious and controlled yet proactive way. The infrastructure capacity for micromobility devices is being developed by extending the cycling networks as part of their vision to reach 700 km by 2030. The case is helpful for policymakers to address similar risks of powered micromobility devices. While it is tricky to handle novel technologies in transportation, the government in Singapore has put safety as the foremost intent in regulating the devices. A bottom-up approach to resolve the problems arising with time was followed to pacify the concerns of all stakeholders. The formation of AMAP comprising a diverse set of people is indicative of that.

7.1. Limitations of Research

While a ban was imposed on the use of powered micromobility devices, the government is still working its way through the various issues by proposing regulations oriented towards introducing the devices in the country again. This study is based on desk-based research, surveys and interviews with officials would throw light on the perceptions of the public and feedback from officials. There are some caveats to the external validity of the findings of this study. The success of implementing the governing strategies to tackle the challenges arising from the adoption of powered micromobility devices is due to Singapore’s unique characteristics. The unique elements are the geography, jurisdictions, the nature of parliamentary government that is a majority rule by one political party, and governance structure that is not multi-level unlike large countries [32].

7.2. Future Research

To lift the ban and kickstart the adoption of powered micromobility devices in full swing, in Singapore, the government will have to improve the existing infrastructure and take a more anticipatory stance of policymaking. The case study shows that the government has already been able to identify and even manage the risks of these devices. However, few hurdles to the safe adoption of these devices still remain. The need for a clear liability regime and inclusiveness in participatory policymaking would be useful in safely adopting powered micromobility devices.

The governance lessons from the case of managing risks from powered PMDs, due to its unique feature of being a city-state and political characteristics, can provide insightful policy guidance and policy learning for jurisdictions that have already adopted or will adopt powered micromobility devices. Since a one size fits all approach will not be appropriate, policymakers must consider the unique features of Singapore before implementing similar legislation. Future work on the regulation of powered micromobility devices could involve examining the risks from adopting and governing strategies implemented in varied jurisdictions.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su13116202/s1, supplementary material A, supplementary material B, and supplementary material C.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, D.P. and A.T.; methodology, A.T. and D.P.; validation, A.T.; formal analysis, D.P. and A.T.; investigation, D.P. and A.T.; resources, A.T.; data curation, D.P.; writing and editing D.P. and A.T.; supervision, A.T.; project administration, A.T.; funding acquisition, A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore.

Acknowledgments

Araz Taeihagh is grateful for the support provided by the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in this study.

References

- Santacreu, A. Safe Micromobility; International Transport Forum: Paris, Frence, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Heineke, K.; Kloss, B.; Scurtu, D.; Weig, F. Micromobility’s 15,000-Mile Checkup. McKinsey Co. 2019. Available online: https://journals.gmu.edu/index.php/jmms/article/view/2894 (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Oeschger, G.; Carroll, P.; Caulfield, B. Micromobility and Public Transport Integration: The Current State of Knowledge. Transp. Res. Part Transp. Environ. 2020, 89, 102628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, H.; de Jamblinne de Meux, L.; Zeller, V.; D’Ans, P.; Ruwet, C.; Achten, W.M. Dockless E-Scooter: A Green Solution for Mobility? Comparative Case Study between Dockless e-Scooters, Displaced Transport, and Personal e-Scooters. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abduljabbar, R.L.; Liyanage, S.; Dia, H. The Role of Micro-Mobility in Shaping Sustainable Cities: A Systematic Literature Review. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 92, 102734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzio, T.J.; Murphy, P.B.; Gazzetta, J.; Dineen, H.A.; Savage, S.A.; Streib, E.W.; Zarzaur, B.L. The Electric Scooter: A Surging New Mode of Transportation That Comes with Risk to Riders. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2020, 21, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassell, E.; Clapperton, A. Consumer Product-Related Injury (2): Injury Related to the Use of Motorised Mobility Scooters. Hospital (Rio J.) 2004, 5, 280–283. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn, J.; Bluth, M.; Christianson, M.; Pressley, J.; Taylor, A.; Macfarlane, G.S.; Chaney, R.A. Considering the Potential Health Impacts of Electric Scooters: An Analysis of User Reported Behaviors in Provo, Utah. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 6344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, G.; Tsao, H.; Randell, T.; Marks, J.; Mackay, P. Impact of Electric Scooters to a Tertiary Emergency Department: 8-Week Review after Implementation of a Scooter Share Scheme. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2019, 31, 930–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nellamattathil, M.; Amber, I. An Evaluation of Scooter Injury and Injury Patterns Following Widespread Adoption of E-Scooters in a Major Metropolitan Area. Clin. Imaging 2020, 60, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikka, N.; Vila, C.; Stratton, M.; Ghassemi, M.; Pourmand, A. Sharing the Sidewalk: A Case of E-Scooter Related Pedestrian Injury. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 37, 1807-e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivedi, T.K.; Liu, C.; Antonio, A.L.M.; Wheaton, N.; Kreger, V.; Yap, A.; Schriger, D.; Elmore, J.G. Injuries Associated with Standing Electric Scooter Use. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e187381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siman-Tov, M.; Radomislensky, I.; Group, I.T.; Peleg, K. The Casualties from Electric Bike and Motorized Scooter Road Accidents. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2017, 18, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Shang, S.; Qi, H.; Yu, G.; Wang, Y.; Chen, P. Simulative Investigation on Head Injuries of Electric Self-Balancing Scooter Riders Subject to Ground Impact. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2016, 89, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copeland, D. Electric Scooters: A New Frontier in Transportation and Products Liability. Rich. JL Tech. 2020, 26, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Taeihagh, A.; de Jong, M.; Klinke, A. Toward a Commonly Shared Public Policy Perspective for Analyzing Risk Coping Strategies. Risk Anal. 2020, 41, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taeihagh, A.; Ramesh, M.; Howlett, M. Assessing the Regulatory Challenges of Emerging Disruptive Technologies. Regul. Gov. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C. When Wheels and Walkers Collide. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/transport/when-wheels-and-walkers-collide (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- SAE J3194: Taxonomy and Classification of Powered Micromobility Vehicles—SAE International. Available online: https://www.sae.org/standards/content/j3194_201911/ (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- LTA Annual Vehicle Statistics 2020-Motor Vehicle Population by Vehicle Type. Available online: https://www.lta.gov.sg/content/dam/ltagov/who_we_are/statistics_and_publications/statistics/pdf/MVP01-1_MVP_by_type.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- LTA LTA|Who We Are. Available online: https://www.lta.gov.sg/content/ltagov/en/who_we_are.html (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- LTA LTA|Getting Around|Active Mobility|Rules & Public Education|Rules & Code of Conduct. Available online: https://www.lta.gov.sg/content/ltagov/en/getting_around/active_mobility/rules_and_public_education/rules_and_code_of_conduct.html (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Wei, T.T. More than 85,000 e-Scooters Registered with LTA as New Rules Kick in. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/transport/more-than-85000-e-scooters-registered-with-lta-as-new-rules-kick-in (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Seawright, J.; Gerring, J.; Seawright, J.; Gerring, J. Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research: A Menu of Qualitative and Quantitative Options. In Case Studies; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2014; p. II213. ISBN 978-1-4462-7448-4. [Google Scholar]

- Teo, G. ‘45-Minute City, 20-Minute Towns’: Advisory Panel Outlines Vision for Land Transport Master Plan 2040—CAN. Available online: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/45-minute-city-20-minute-towns-land-transport-master-plan-2040-11114494 (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Land Transport Authority. LTA Annual Report 2019/20 Riding It Out Together; Land Transport Authority: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, A. 9 in 10 PMDs and E-Bikes Confiscated Due to Their Size, Weight or Top Speed: LTA. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/transport/9-in-10-personal-mobility-devices-and-e-bikes-confiscated-due-to-their-size (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Loh, V. Bill Passed to Boost LTA’s Enforcement Efforts, Set New Fire Standard for PMDs. Available online: https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/bill-passed-boost-ltas-enforcement-efforts-set-new-fire-standard-pmds (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- LTA LTA|Industry & Innovations|Industry Matters|Regulations & Licensing|Active Mobility|Shared Mobility Services Licensing. Available online: https://www.lta.gov.sg/content/ltagov/en/industry_innovations/industry_matters/regulations_licensing/active_mobility/shared_mobility_services_licensing.html (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Salim, Z. Scoot over, Bike-Sharing—3rd e-Scooter Sharing Startup Rolling into Town This September. Available online: https://www.asiaone.com/singapore/scoot-over-bike-sharing-3rd-e-scooter-sharing-startup-rolling-town-september (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Tan, S.; Taeihagh, A. Adaptive Governance of Autonomous Vehicles: Accelerating the Adoption of Disruptive Technologies in Singapore. Gov. Inf. Q. 2021, 38, 101546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.T. Parliament: PMD Safety Certification Deadline Brought Forward to July 1, 2020; Mandatory Inspection for All e-Scooters from April 1. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/transport/pmd-safety-certification-deadline-brought-forward-to-july-1-2020-mandatory (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Yusof, Z.M. Home Front: Cranking up Safety for Cyclists on Roads. Available online: https://uat.straitstimes.com/opinion/cranking-up-safety-for-cyclists-on-roads (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- LTA. Land Transport Master Plan 2013; 2013. Available online: https://www.lta.gov.sg/content/dam/ltagov/who_we_are/statistics_and_publications/master-plans/pdf/LTMP2013Report.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources and Ministry of National Development. Sustainable Singapore Blueprint 2015; 2014. Available online: https://www.nccs.gov.sg/docs/default-source/default-document-library/sustainable-singapore-blueprint-2015.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Active Mobility Advisory Panel. Recommendations on Rules and Code of Conduct for Cycling and the Use of Personal Mobility Devices; 2016. Available online: https://www.lta.gov.sg/content/ltagov/en/newsroom/2016/3/2/active-mobility-advisory-panel-recommends-rules-and-code-of-conduct-for-safe-sharing-of-paths.html (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Lim, A. Housewife Still Unconscious after Accident Involving Electric Scooter; Teenager Arrested. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/courts-crime/housewife-still-unconscious-after-accident-involving-electric-scooter (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Abdullah, Z. Trial to Allow All-Day Access for Folding Bikes, Personal Mobility Devices on Trains and Buses to Begin in December. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/transport/trial-to-allow-all-day-access-for-folding-bikes-pmds-on-trains-and-buses-to (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Active Mobility Act 2017—Singapore Statutes Online. Available online: https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Act/AMA2017 (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Active Mobility Bill—Singapore Statutes Online. Available online: https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Bills-Supp/40-2016/Published/20161109?DocDate=20161109 (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Singapore Statutes Online Active Mobility Bill—Singapore Statutes Online. Available online: https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Bills-Supp/40-2016/Published/20161109?DocDate=20161109 (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Cheong, D. MPs Call for Helmet Use, Courses to Ensure Safe Public Paths. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/transport/mps-call-for-helmet-use-courses-to-ensure-safe-public-paths (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Tan, C. Stiffer Fines, Possible Jail Time for Offences Involving Personal Mobility Devices from Jan 15. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/transport/fines-for-personal-mobility-device-offences-to-treble-from-jan-15 (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Lim, A. First Phase to Transform Ang Mo Kio into Cycling and Walking Town Completed. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/transport/first-phase-to-transform-ang-mo-kio-into-cycling-and-walking-town-completed (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Abdullah, Z. A Wheel Menace: Spike in Number of Accidents Involving e-Bikes in 2016. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/transport/a-wheel-menace (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Hong, J.; Huiwen, N. Spring Singapore Uncovers 6 E-Scooter Suppliers Selling Unregistered Charging Adaptors; Seizes 175 Adaptors. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/spring-singapore-uncovers-6-e-scooter-suppliers-selling-unregistered-charging-adaptors (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Lim, A.; Tee, C.; Lee, G. PMD Users Openly Flout Law in Geylang. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/transport/pmd-users-openly-flout-law-in-geylang (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Lim, A. Parliament: About Three Accidents a Week Involving Personal Mobility Device Users. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/politics/parliament-average-of-three-accidents-a-month-involving-pedestrians-and-personal-mobility (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Ming, T.E. Registration for E-Scooters Part of Review of Code of Conduct for PMDs. Available online: https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/registration-e-scooters-part-review-code-conduct-pmds (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Lim, A. Stiffer Penalties for Errant PMD Users Timely, but Experts Also Call for More Education. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/transport/stiffer-penalties-for-errant-pmd-users-timely-but-experts-also-call-for-more (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Abdullah, Z. 38 Caught Riding PMDs on Roads since Start of Year. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/transport/38-caught-riding-pmds-on-roads-since-start-of-year (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Abdullah, Z. New Safe Riding Guide for Food Delivery Riders. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/new-safe-riding-guide-for-food-delivery-riders (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Abdullah, Z. Parliament: Mandatory Registration of e-Scooters from Second Half of 2018. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/politics/parliament-mandatory-registration-of-e-scooters-from-second-half-of-2018 (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Lim, A. Speed Guns Deployed to Curb Reckless Riding. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/transport/speed-guns-deployed-to-curb-reckless-riding (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Lim, A. LTA Ropes in Auxiliary Police Officers to Beef up Enforcement against Errant Cyclists, PMD Riders. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/transport/lta-ropes-in-auxiliary-police-officers-to-beef-up-enforcement-against-errant (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Yng, L.P. Ban Power-Assisted PMDs. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/forum/letters-on-the-web/ban-power-assisted-pmds (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Wong, L. PMD Dangers from Bad Batteries. Available online: https://www.tnp.sg/news/singapore/pmd-dangers-bad-batteries (accessed on 10 March 2021).