Influence of Fiscal Policies and Labor Market Characteristics on Sustainable Social Insurance Budgets—Empirical Evidence from Central and Eastern European Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

3. Materials and Methods

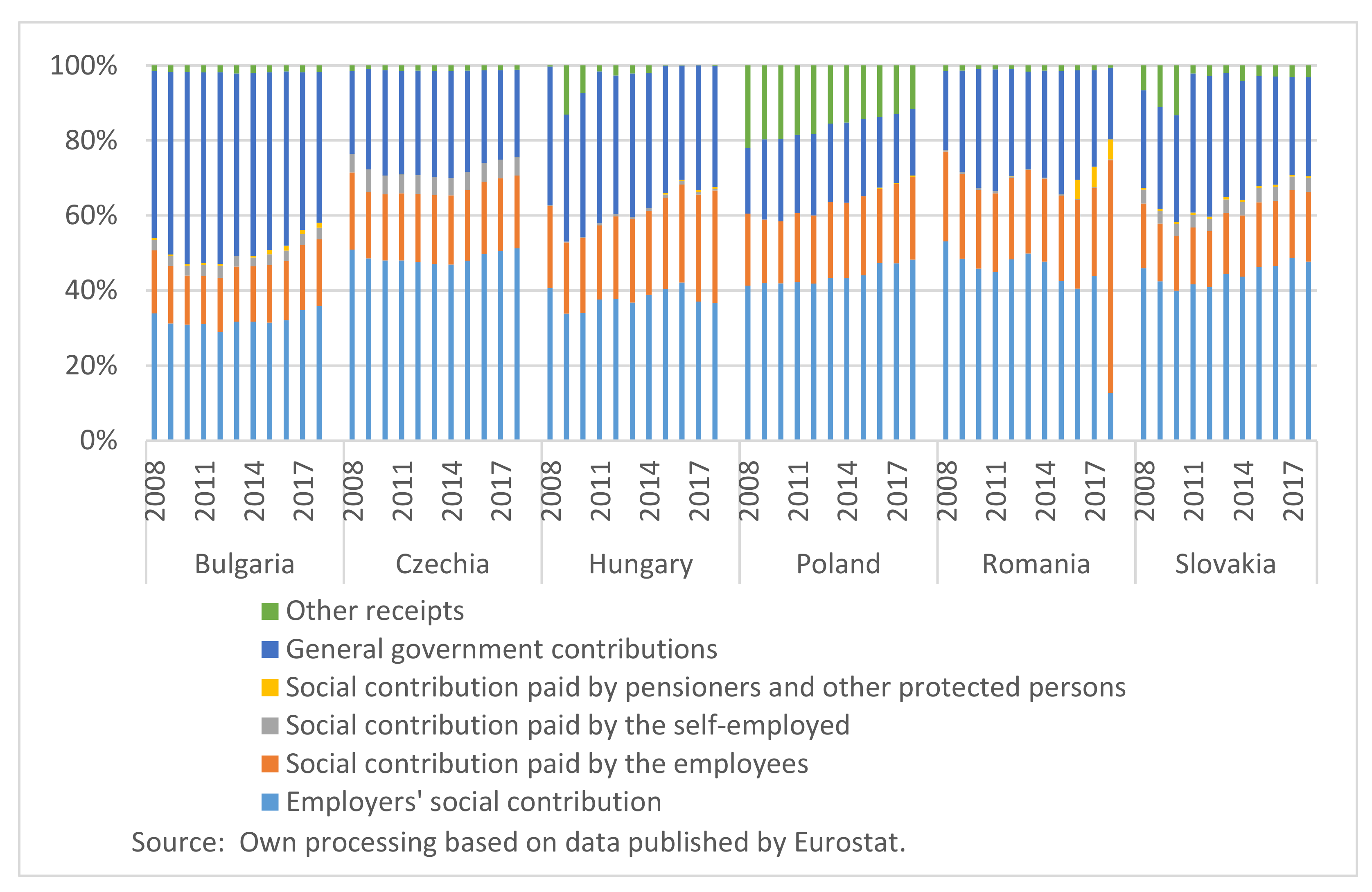

- financing source of social insurance budgets: revenues collected from social contributions (SPR_SC);

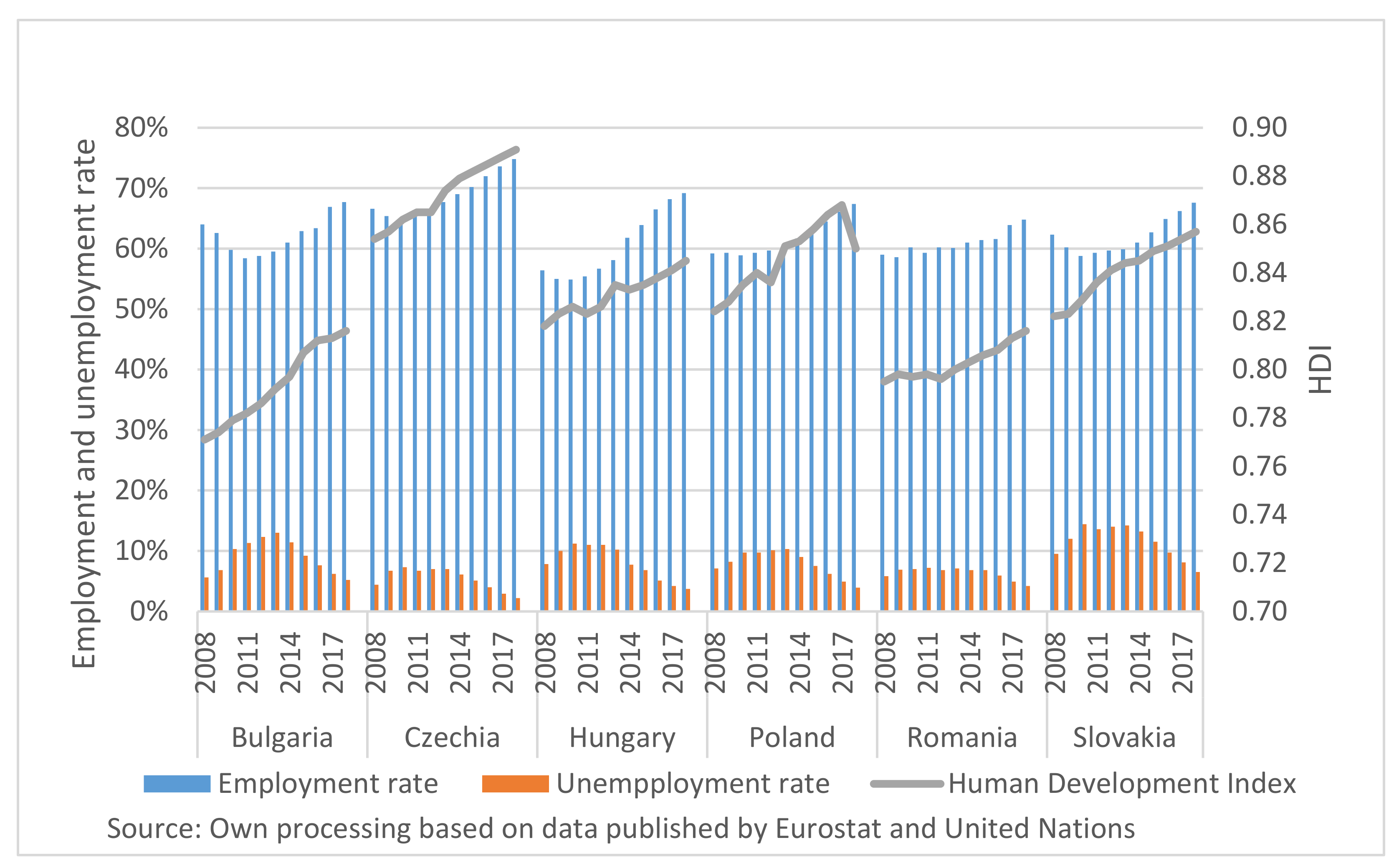

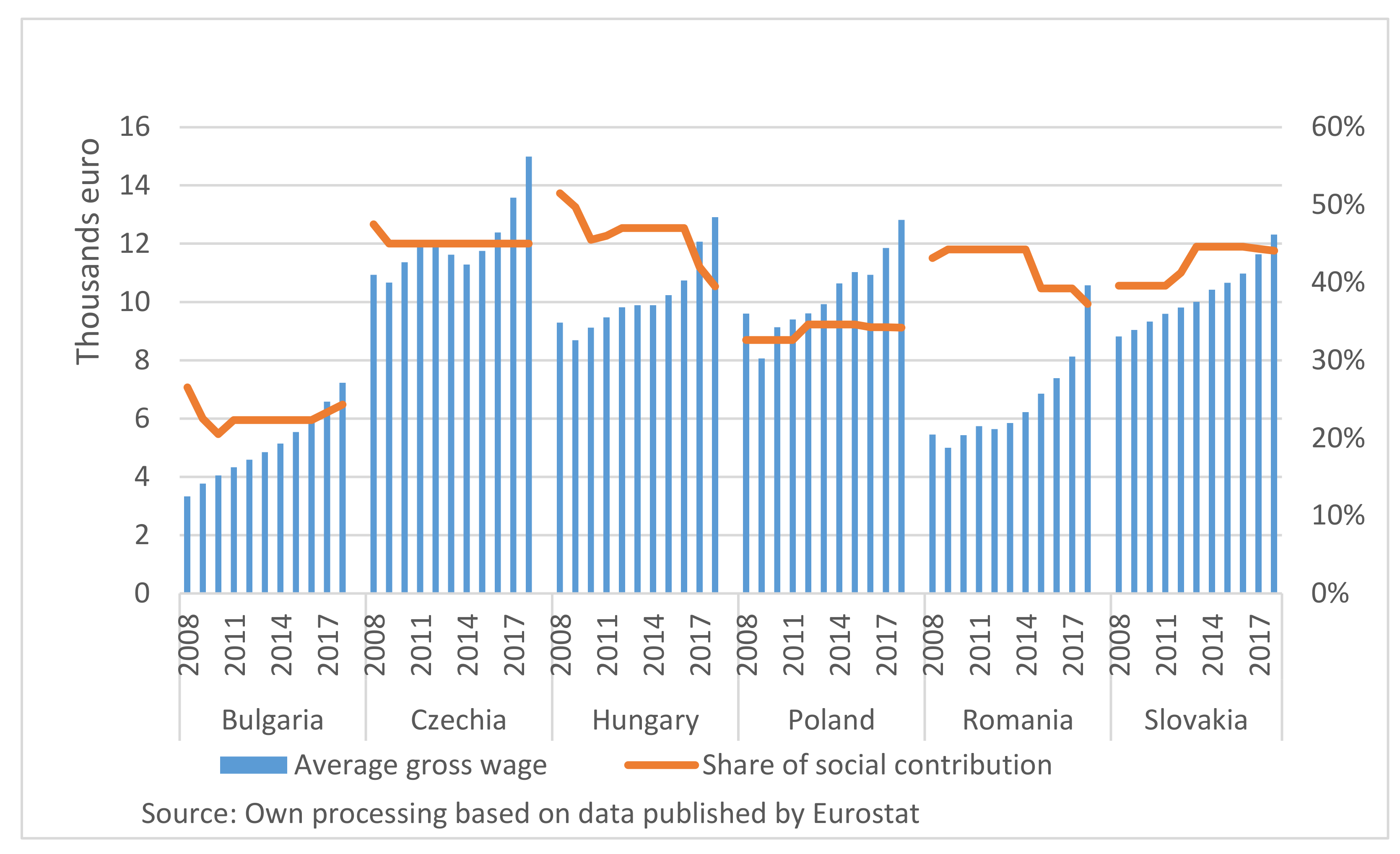

- socio-economic characteristics of the labor market: employment rate (ER), unemployment rate (UR), human development index (HDI), average gross wage (AGW), share of social contributions (SCQ);

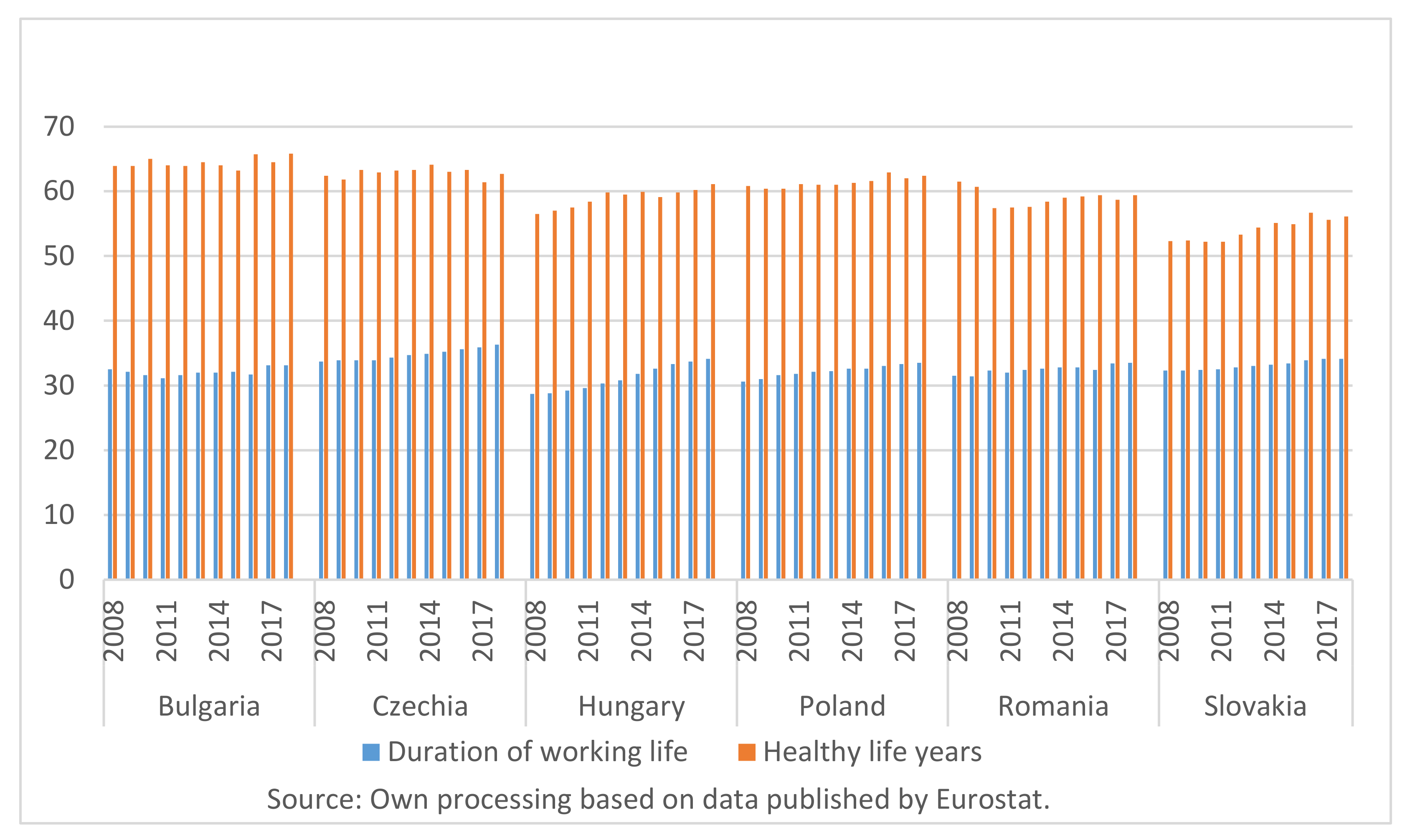

- socio-medical characteristics of the labor market: duration of the working life (DWL), healthy life expectancy (HLY), working accidents (WA).

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Labour Organization. The protection of the right to Social Security in European Constitutions: Compendium of provisions of European Constitutions and Comparative tables (Online Version). Available online: http://www.ilo.org/global/standards/subjects-covered-by-international-labour-standards/social-security/WCMS_191459/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Sabates-Wheeler, R.; Devereux, S. Transformative social protection: The currency of social justice. In Social Protection for the Poor and Poorest. Risk, Needs and Rights, Barrientos, Hulme; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Boadway, R.; Keen, M. Redistribution. In Handbook of Income Distribution; Atkinson, A.B., Bourguignon, F., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, C.J.; Pontusson, J. Workers, worries and welfare states: Social protection and job insecurity in 15 OECD countries. Eur. J. Political Res. 2007, 46, 211–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sverke, M.; Låstad, L.; Hellgren, J.; Richter, A.; Näswall, K. A Meta-Analysis of Job Insecurity and Employee Performance: Testing Temporal Aspects, Rating Source, Welfare Regime, and Union Density as Moderators. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortès-Franch, I.; Puig-Barrachina, V.; Vargas-Leguás, H.; Arcas, M.; Artazcoz, L. Is Being Employed Always Better for Mental Wellbeing Than Being Unemployed? Exploring the Role of Gender and Welfare State Regimes during the Economic Crisis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iparraguirre, J.L. Economics and Ageing—Volume III: Long-Term Care and Finance; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hansmann, R.; Mieg, H.A.; Frischknecht, P. Principal sustainability components: Empirical analysis of synergies between the three pillars of sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2012, 19, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. How Labour and Macroeconomic Policies Can Contribute towards the Achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals? Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/cimem8d8_en.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Esping-Andersen, G. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sapir, A. Globalisation and the reform of European social models. J. Common Mark. Stud. 2006, 44, 369–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, M.F. Essays on Early Life Circumstances, Health and Labor Market Outcomes in Europe. Ph.D. Thesis, Instituto Universitario de Estudos e Desenvolvemento de Galicia (IDEGA), Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Orosz, A. The Emergence of East Central Europe in a Welfare Regime Typology. Bord. Crossing 2019, 9, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricker, D.; Ibbitson, J. Empty Planet: The Shock of Global Population Decline; Crown Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, E. Female Education and Childbearing: A Closer Look at the Data. In Investing in Health. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/health/female-education-and-childbearing-closer-look-data (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Simionescu, M. What Drives Economic Growth in some CEE Countries? Studia Univ. Vasile Goldis Arad Econ. Ser. 2018, 28, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Precup, M. The Economic Growth and the Opportunity for the Private Equity Funds to Divest: An Empirical Analysis for Eastern Europe. Studia Univ. Vasile Goldis Arad Econ. Ser. 2019, 29, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumiter, F.C.; Jimon, Ș.A. Theoretical and Practical Assessments of Transfer Prices. Legal Evidence from Romanian Case Law. J. Leg. Stud. 2020, 26, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzmann, R.; Koettl, J. Stability of Pension, Health, and other Social Benefits: Facts, Concepts, and Issues. CESifo Econ. Stud. 2015, 61, 377–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atoyan, R.; Christiansen, L.; Dizioli, A.; Ebeke, C.; Ilahi, N.; Ilyina, A.; Mehrez, G.; Qu, H.; Raei, F.; Rhee, A.; et al. Emigration and Its Economic Impact on Eastern Europe. IMF Staff Discussion Note SDN/16/07. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/sdn/2016/sdn1607.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Clements, B.; Dybczak, K.; Gaspar, V.; Gupta, S.; Soto, M. The Fiscal Consequences of Shrinking Populations, in IMF Staff Discussion Note SDN/15/2. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/sdn/2015/sdn1521.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Vučković, V.; Škuflić, L. The effect of emigration on financial and social pension system sustainability in EU new member states: Panel data analysis. Econ. Sociol. 2021, 14, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission European. Economic Forecast—Spring 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/european-economic-forecast-spring-2020_en (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Albu, L.L.; Preda, C.I.; Lupu, R.; Dobrotă, C.E.; Călin, G.M.; Boghicevici, C.M. Estimates of dynamics of the COVID19 pandemic and of its impact on the economy. Rom. J. Econ. Forecast. 2020, 23, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ladi, S.; Tsarouhas, D. EU economic governance and Covid-19: Policy learning and windows of opportunity. J. Eur. Integr. 2020, 42, 1041–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue, C.; Sologon, D.M.; Kyzyma, I.; McHale, J. Modelling the distributional impact of the COVID—19 crisis. Fisc. Stud. 2020, 41, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCloskey, B.; Zumla, A.; Ippolito, G.; Blumberg, L.; Arbon, P.; Cicero, A.; Endericks, T.; Lim, P.L.; Borodina, M. Mass gathering events and reducing further global spread of COVID-19: A political and public health dilemma. Lancet 2020, 395, 1096–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronsson, T.; Micheletto, L. Optimal Redistributive Income Taxation and Efficiency Wages. Scand. J. Econ. 2021, 123, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libanova, E.M.; Makarova, O.V.; Sarioglo, V.G. Activation Policy as an Investment in Human Capital: Theory and Practice. Sci. Innov. 2020, 16, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omran, E.A.M.; Bilan, Y. The Impact of Fiscal Policy on the Unemployment Rate in Egypt. Montenegrin J. Econ. 2020, 16, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, A.; Juhasz, T.; Kalman, B. The Role of Innovation and Human Factor in the Development of East Central Europe. Montenegrin J. Econ. 2020, 16, 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csath, M. Competitiveness Based on Knowledge and Innovation. Public Financ. Q. Hung. 2018, 63, 64–79. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, C. Optimal taxation with unobservable investment in human capital. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 2020, 72, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliendo, F.N.; Findley, T.S. Myopia, education, and social security. Int. Tax Public Financ. 2020, 27, 694–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, F.W.; Brandli, L.L.; Lange, S.A.; Rayman-Bacchus, L.; Platje, J. COVID-19 and the UN sustainable development goals: Threat to solidarity or an opportunity? Sustainability 2020, 12, 5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörisch, J. The relation of COVID-19 to the UN sustainable development goals: Implications for sustainability accounting, management and policy research. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2020, 2040–8021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liargovas, P.; Psychalis, M.; Apostolopoulos, N. Fiscal policy, growth and entrepreneurship in the EMU. Eur. Politics Soc. 2021, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulos, N.; Psychalis, M.; Liargovas, P.; Pistikou, V. Investigating Government lending during an economic crisis: A comparative analysis of four EU countries. Eur. Politics Soc. 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.; Rahaman, M. The Post COVID-19 Global Economy: An Econometric Analysis. IOSR J. Econ. Financ. 2021, 12, 22–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bulba, V.G.; Goncharenko, M.V.; Yevtuxov, O.V. Fiscal mechanism in public administration of social risks. Cuest. Politicas 2021, 39, 531–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szarowska, I. Personal income taxation in a context of a tax structure. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 12, 662–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikhonova, A.; Goncharenko, L.; Melnikova, N.; Malkova, Y. An Assessment of the Influence of the Current National Economy Development State upon Personal Income Taxation System. In Proceedings of the Vision 2020: Sustainable Economic Development and Application of Innovation Management, 32nd Conference of the International-Business-Information-Management-Association (IBIMA), Seville, Spain, 15–16 November 2018; Soliman. pp. 7982–7989. [Google Scholar]

- Belev, S.G.; Moguchev, N.S.; Vekerle, K.V. Fiscal Effects of Labour Income Tax Changes in Russia. J. Tax Reform 2020, 6, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szikra, D. Reversing Privatization and Re-Nationalizing Pensions in Hungary. ESS—Working Paper No. 66, Social Protection Department. Available online: https://www.social-protection.org/gimi/RessourcePDF.action?id=55307 (accessed on 16 March 2021).

- OECD. Pension Markets in Focus. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/finance/private-pensions/pensionmarketsinfocus.htm (accessed on 16 March 2021).

- Balazs, E. The impact of changes in second pension pillars on public finances in Central and Eastern Europe: The case of Poland. Econ. Syst. 2013, 37, 473–491. [Google Scholar]

- Carp, A. Scenarii privind evoluţia sistemului de pensii private din România. Rom. Stat. Rev. 2018, 4, 186–195. [Google Scholar]

- Staubli, S.; Zweimüller, J. Does raising the early retirement age increase employment of older workers? J. Public Econ. 2013, 108, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engels, B.; Geyer, J.; Haan, P. Pension incentives and early retirement. Labour Econ. 2017, 47, 216–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimon, Ș.A.; Balteș, N.; Dumiter, F. Empirical Approaches upon Pension Systems in Central and Eastern European Countries. Triangle Assessment: Free Movement of People, Labor Market and Population Health Features. Studia Univ. “Vasile Goldis” Econ. Ser. 2020, 30, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godınez-Olivares, H.; Del Carmen Boado-Penas, M.; Haberman, S. Optimal strategies for pay-as-you-go pension finance: A sustainability framework. Insur. Math. Econ. 2016, 69, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Typology of Social Protection Systems | Main Features | Representative Countries |

|---|---|---|---|

| Esping-Andersen [10] | Liberal |

| Great Britain, Ireland |

| Conservative–corporate |

| France, Belgium, Germany, Italy, Austria | |

| Socio–democratic |

| Sweden, Norway, Denmark | |

| Sapir [11] | Anglo-Saxon |

| Great Britain, Ireland |

| Northern |

| Sweden, Norway | |

| Continental |

| France, Germany | |

| Mediterranean |

| Italy | |

| Flores [12]; Orosz [13] | In transition |

| CEE |

| Mean | Median | Maximum | Minimum | Std. Dev. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPR_SC | 11.95455 | 12.2 | 15.1 | 8.3 | 1.839079 |

| ER | 62.71667 | 61.75 | 74.8 | 54.9 | 4.393057 |

| UR | 8.025758 | 7.15 | 14.4 | 2.2 | 2.975609 |

| HDI | 0.831242 | 0.834 | 0.891 | 0.771 | 0.029443 |

| AGW | 9059.74 | 9603.075 | 14,984.75 | 3328.05 | 2754.822 |

| SCQ | 38.7753 | 42.575 | 51.5 | 20.5 | 8.5122 |

| DWL | 32.62879 | 32.6 | 36.3 | 28.7 | 1.527569 |

| HLY | 60.11364 | 60.75 | 65.8 | 52.2 | 3.533701 |

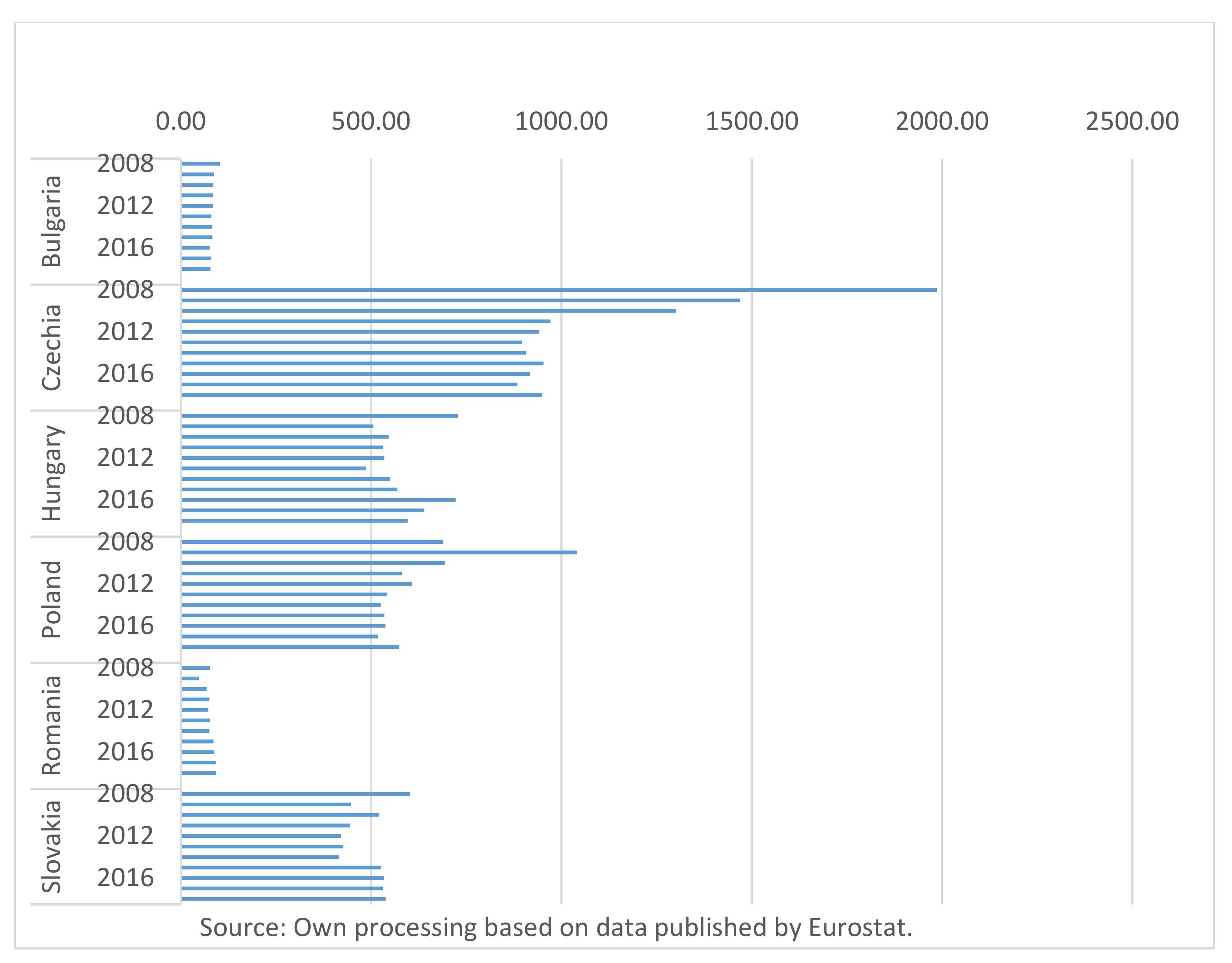

| WA | 494.0083 | 528.39 | 1987.06 | 47.93 | 386.5009 |

| Skewness | Kurtosis | Jarque-Bera | Probability | ||

| SPR_SC | −0.22176 | 2.133158 | 2.607332 | 0.271534 | |

| ER | 0.569601 | 2.94567 | 3.577017 | 0.167209 | |

| UR | 0.37203 | 2.378647 | 2.584187 | 0.274695 | |

| HDI | −0.00516 | 2.314791 | 1.291448 | 0.524283 | |

| AGW | −0.35814 | 2.223116 | 3.070643 | 0.215386 | |

| SCQ | −0.88529 | 2.550803 | 9.175907 | 0.010174 | |

| DWL | −0.23139 | 3.60206 | 1.585759 | 0.45254 | |

| HLY | −0.62658 | 2.651258 | 4.653139 | 0.09763 | |

| WA | 1.099442 | 5.134599 | 25.82692 | 0.000002 | |

| ER | UE | HDI | AGW | SCQ | DWL | HLY | WA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER | 1.00 | |||||||

| UE | −0.71 | 1.00 | ||||||

| HDI | 0.61 | −0.26 | 1.00 | |||||

| AGW | 0.56 | −0.28 | 0.94 | 1.00 | ||||

| SCQ | 0.08 | −0.15 | 0.49 | 0.56 | 1.00 | |||

| DWL | 0.91 | −0.50 | 0.62 | 0.53 | 0.15 | 1.00 | ||

| HLY | 0.36 | −0.46 | −0.02 | −0.16 | −0.51 | 0.18 | 1.00 | |

| WA | 0.39 | −0.22 | 0.75 | 0.72 | 0.47 | 0.35 | 0.04 | 1.00 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGW | 0.0005 *** (7.42) | ||

| DWL | −0.037 ** (−2.81) | −0.33 *** (−4.75) | |

| HDI | 50.18 *** (10.48) | ||

| HLY | −0.15 * (−1.41) | ||

| Second Pillar | −1.13 ** (−2.23) | ||

| SCQ | 0.10 *** (9.01) | 0.05 *** (5.79) | |

| UR | −0.08 *** (−2.86) | −0.03 (−0.73) | |

| ER | 0.20 *** (4.22) | ||

| WA | 0.002 *** (7.92) | 0.001 (1.60) | |

| INTERCEPT | 6.42 *** (2.25) | −20.61 *** (−6.76) | 15.37 *** (3.51) |

| R-squared | 76.82% | 90.01% | 79.20% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Popa, A.F.; Jimon, S.A.; David, D.; Sahlian, D.N. Influence of Fiscal Policies and Labor Market Characteristics on Sustainable Social Insurance Budgets—Empirical Evidence from Central and Eastern European Countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6197. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116197

Popa AF, Jimon SA, David D, Sahlian DN. Influence of Fiscal Policies and Labor Market Characteristics on Sustainable Social Insurance Budgets—Empirical Evidence from Central and Eastern European Countries. Sustainability. 2021; 13(11):6197. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116197

Chicago/Turabian StylePopa, Adriana Florina, Stefania Amalia Jimon, Delia David, and Daniela Nicoleta Sahlian. 2021. "Influence of Fiscal Policies and Labor Market Characteristics on Sustainable Social Insurance Budgets—Empirical Evidence from Central and Eastern European Countries" Sustainability 13, no. 11: 6197. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116197

APA StylePopa, A. F., Jimon, S. A., David, D., & Sahlian, D. N. (2021). Influence of Fiscal Policies and Labor Market Characteristics on Sustainable Social Insurance Budgets—Empirical Evidence from Central and Eastern European Countries. Sustainability, 13(11), 6197. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116197