Best Content Standards in Sports Career Education for Adolescents: A Delphi Survey of Korean Professional Views

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Career Development for Adolescents

2.2. Sports Career Education

3. Methods

3.1. The Delphi Technique

3.2. Delphi Participants in the Expert Panel

3.3. Delphi Procedure

3.4. The Questionnaire

3.5. Data Analysis

3.6. Ethics

4. Results

4.1. First Round

4.2. Second and Third Round

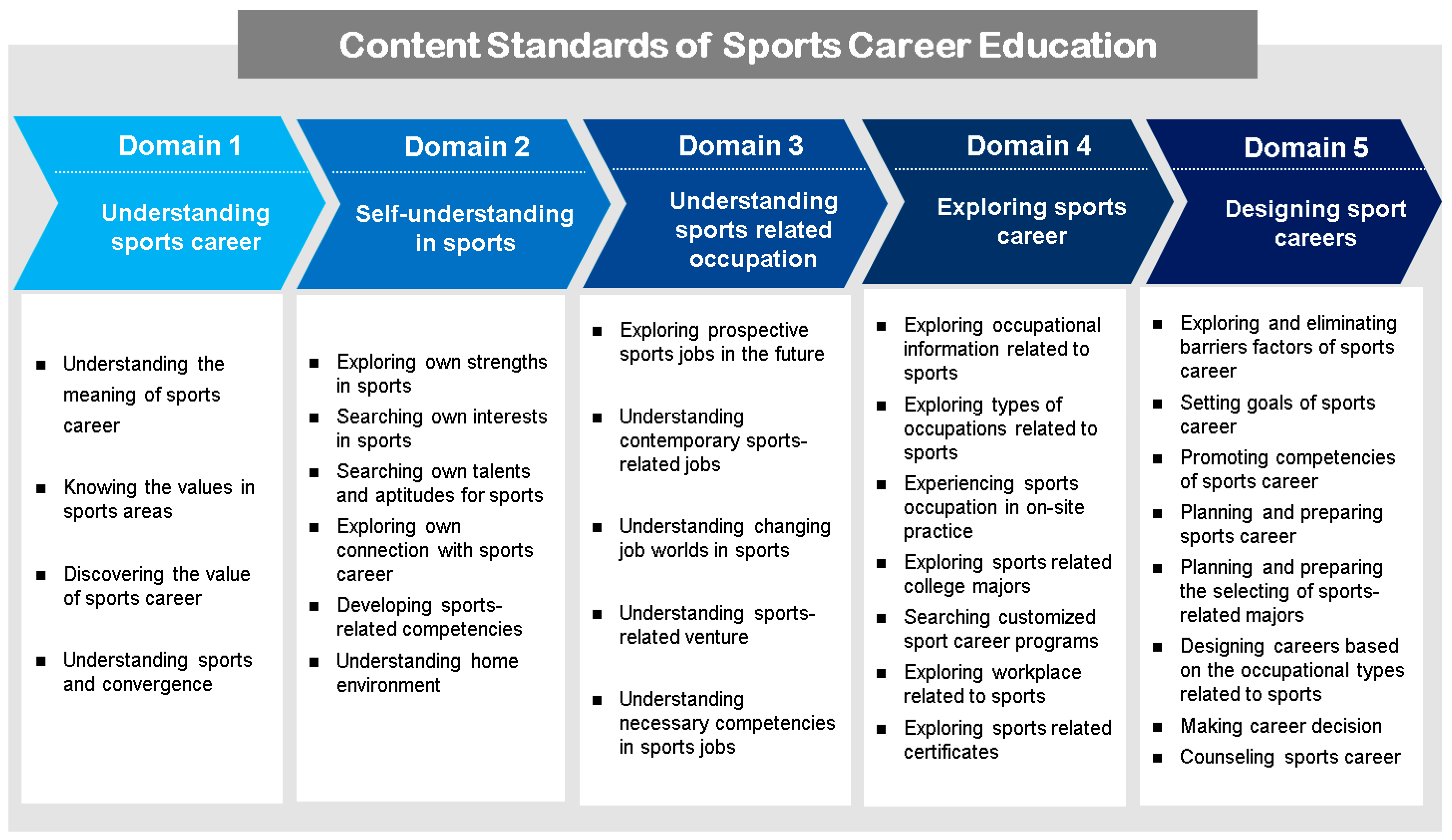

4.3. The Final Content Standards of Sports Career Education

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Suggestions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Choi, Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, S. Career development and school success in adolescents: The role of career interventions. Career Dev. Q. 2015, 63, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; You, J. Exploring curriculum directions for Korean sport career education. Asian J. Phys. Educ. Sport Sci. 2020, 8, 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, S. Evaluating a life centered career education curriculum to support student success. Res. High. Educ. J. 2018, 35, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Conkel-Ziebell, J.; Turner, S.; Gushue, G. Testing an integrative contextual career development model with adolescents from high-poverty urban areas. Career Dev. Q. 2018, 66, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Lee, G.; Kim, J.; Lee, M. Equity in career development of high school students in South Korea: The role of school career education. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, M.; Yau, F.; Tsui, J.; Shao, S.; Tsang, J.; Lee, B. Career education and vocational training in HongKong: Implications for school-based career counselling. Int. J. Adv. Couns. 2019, 41, 449–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, A. Being an athlete and being a young person: Technologies of the self in managing an athletic career in youth ice hockey in Finland. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2020, 55, 310–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronkainen, N.; Ryba, T. Understanding youth athletes’ life designing processes through dream day narratives. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 108, 422–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Kong, N.; Skaggs, S.; Yang, A. An ecological perspective on youth career education in transitioning societies: China as an example. J. Career Dev. 2019, 46, 651–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemery, D. The Pursuit of Sporting Excellence: A Study of Sport’s Highest Achievers; Willow: London, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Nurmi, J. How do adolescents see their future? A review of the development of future orientation and planning. Dev. Rev. 1991, 11, 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronkainen, N.; Ryba, T.; Selanne, H. She is where I’d want to be in my career: Youth athletes’ role models and their implications for career and identity construction. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 45, 101562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuerth, S.; Lee, M.; Alfermann, D. Parental involvement and athletes’ career in youth sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2004, 5, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikander, J.; Ronkainen, N.; Korhonen, N.; Saarinen, M.; Ryba, T. From athletic talent development to dual career development? A case study in a Finnish high performance sports environment. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2020, 8, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryda, T.; Ronkainen, N.; Douglas, K.; Aunola, K. Implications of the identity position for dual career construction: Gendering the pathways to (Dis) continuation. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2021, 53, 101844. [Google Scholar]

- Stambulova, N.; Wylleman, P. Psychology of athletes’ dual careers: A state-of the art critical review of the European discourse. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 42, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torregrosa, M.; Ramis, Y.; Pallares, S.; Azocar, F.; Selva, C. Olympic athletes back to retirement: A qualitative longitudinal study. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 21, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Kwon, H.; You, J. Where are we going? Narrative accounts of female high school student-athletes in the republic of Korea. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2015, 10, 1071–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, A. Review and critique of the Korean national school career education goals and performance criterion. Educ. Cult. Res. 2018, 24, 677–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keele, S.; Swann, R.; Davie-Smythe, A. Identifying best practice in career education and development in Australian Secondary schools. Aust. Counc. Educ. Res. 2020, 29, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, W. Career education. What we know, what we need to know. Aust. J. Career Dev. 2001, 10, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paviotti, G. The challenge of career education. Educ. Sci. Soc. 2020, 1, 360–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, L.; Datu, J. Triarchic model of grit dimensions as predictors of career outcomes. Career Dev. Q. 2020, 68, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Super, D.; Savickas, M.; Super, C. The life-span, life-space approach to careers. In Career Choice and Development, 3rd ed.; Brown, D., Brooks, L., Associates, Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 121–178. [Google Scholar]

- Super, D. A life-span, life-space approach to career development. In Career Choice and Development, 2nd ed.; Brown, D., Brooks, L., Associates, Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 197–261. [Google Scholar]

- Del Corso, J.; Rehfuss, M. The role of narrative in career construction theory. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 79, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, P.; Taber, B. Career construction and subjective well-being. J. Career Assess. 2008, 6, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapan, R.T. Career Development across the K-16 Years: Bridging the Present to Satisfying and Successful Futures; American Counseling Association: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Salmela, J.H. Phases and transitions across sport careers. In Psycho-Social Issues and Interventions in Elite Sports; Hackfort, D., Ed.; Lang: Frankfurt, Germany, 1994; pp. 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Dandara, O. Career education in the context of lifelong learning. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 142, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moote, J.; Archer, L. Failing to deliver? Exploring the current status of career education provision in England. Res. Pap. Educ. 2018, 33, 187–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, M.; Blustein, D.; Liang, B.; Klein, T.; Etchie, Q. Applying the psychology of working theory for transformative career education. J. Career Dev. 2019, 46, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welde, A.; Bernes, T.; Gunn, T.; Ross, S. Career education at the elementary school level: Student and intern teacher perspectives. J. Career Dev. 2016, 43, 426–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ince, M. Supporting learning of practitioners and early career scholars in physical education and sports pedagogy. Sport Educ. Soc. 2019, 24, 584–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerstajn, R.; Topic, M. Motivation of Slovenian and Norwegian Nordic athletes towards sports, education, and dual career. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Res. 2017, 4, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Raalte, J.; Andrews, S.; Cornelius, A.; Brewer, B.; Petitpas, A. Student-athlete career self-efficacy: Workshop development and evaluation. J. Clin. Sport Psychol. 2017, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helen-Hart, R. Career education discourse: Promoting student employability in a university career center. Qual. Res. Educ. 2019, 8, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, G.; McCrone, T.; Wade, P. Young people’s decision-making: The importance of high quality school-based careers education, information, advice, and guidance. Res. Pap. Educ. 2013, 28, 459–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qawasmi, J. Selecting a contextualized set of urban quality of life indicators: Results of a Delphi consensus procedure. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, R.; San-Jose, L.; Retolaza, J. Improvement actions for a more social and sustainable public procurement: A Delphi Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castarlenas, E.; Roy, R.; Salvat, I.; Montesó-Curto, P.; Miró, J. Educational needs and resources for teachers working with students with chronic pain: Results of a Delphi study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson, F.; Keeney, S.; McKenna, H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000, 32, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boulkedid, R.; Abdoul, H.; Loustau, M.; Sibony, O.; Alberti, C. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariff, N. Utilizing the Delphi survey approach: A review. J. Nurs. Care 2015, 4, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, A.J.; Marchildon, G.P. Using the Delphi method for qualitative, participatory action research in health leadership. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2014, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lindgren, B.M.; Lundman, B. Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: A discussion paper. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 56, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawshe, C.H. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers. Psychol. 1975, 28, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Yu, S.; Luo, H.; Lin, X. Consensus convergence in large-group social network environment: Coordination between trust relationship and opinion similarity. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 217, 106828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamanasuskas, V.; Augienne, D. Lithuanian gymnasium students’ career education: Professional self-determination context. Psychol. Thought 2019, 12, 93–116. [Google Scholar]

- You, J. Understanding the educational meanings and orientations of physical activity as the essence and tool of physical education content. J. Curric. Eval. 2007, 10, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, L.; Peralmutter, S.; Keenan, K.; Divver, C.; Goroochurn, P. Career readiness programming for youth in foster care. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 89, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, R.; Volkoff, V.; Keating, J.; Watts, T.; Helme, S.; Rice, S.; Pannell, S. Making Career Development Core Business; Office for Policy, Research and Innovation, Department of Education and Early Childhood Development of Education and Early Childhood Development and Department of Business and Innovation: Melbourne, Australia, 2010; Available online: http://iccdpp.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Making-Career-Development-Core-Business.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Arghode, V.; Heminger, S.; McLean, G. Career self-efficacy and education abroad: Implications for future global workforce. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2020, 45, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, C.; Lee, E.; Jang, H. The meaning of experience of gamification job creation career education program using board game to adolescent. J. Child Educ. 2021, 30, 125–137. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, A.; Denis, V.; Schleicher, A.; Ekhtiari, H.; Forsyth, T.; Liu, E.; Chambers, N. Dream Jobs? Teenagers’ Career Aspirations and the Future of Work; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, D. Role models in career development: New directions for theory and research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 65, 134–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, P.; Restubog, S.; Ocampo, A.; Wang, L.; Tang, R. Role modeling as a socialization mechanism in the transmission of career adaptability across generations. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 111, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galipeau, J.; Trudel, P. Athlete learning in a community of practice: Is there a role for the coach. In The Sports Coach as Educator: Re-Conceptualising Sports Coaching; Jones, R., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 77–94. [Google Scholar]

| Domains | Content Elements |

|---|---|

| 1.1 Understanding the meaning of a sports career |

| 1.2 Understanding sports history | |

| 1.3 Knowing the values in sports areas | |

| 1.4 Discovering the value of a sports career | |

| 1.5 Understanding sports and convergence | |

| 2.1 Exploring one’s own strengths in sports |

| 2.2 Searching for one’s own interest in sports | |

| 2.3 Searching for one’s own talent and aptitude for sports | |

| 2.4 Exploring one’s own connection with the sports career | |

| 2.5 Developing sports-related competencies | |

| 2.6 Understanding the home environment | |

| 2.7 Connecting sports careers with one’s personality | |

| 3.1 Exploring prospective sports jobs |

| 3.2 Understanding contemporary sports-related jobs | |

| 3.3 Understanding the changing job world in sports | |

| 3.4 Understanding sports-related ventures | |

| 3.5 Understanding necessary competencies required for sports jobs | |

| 3.6 Understanding the ethics of sports-related occupations | |

| 4.1 Exploring occupational information related to sports |

| 4.2 Exploring types of occupations related to sports | |

| 4.3 Experiencing sports occupations through on-site practice | |

| 4.4 Exploring sports-related majors | |

| 4.5 Searching for customized sports career programs | |

| 4.6 Exploring workplaces related to sports | |

| 4.7 Exploring sports-related certificates | |

| 5.1 Exploring and eliminating factors that act as barriers for sports careers |

| 5.2 Setting goals for sports careers | |

| 5.3 Promoting competencies required for sports careers | |

| 5.4 Planning and preparing for sports careers | |

| 5.5 Planning and preparing for the selection of sports-related majors | |

| 5.6 Designing careers based on the occupational types related to sports | |

| 5.7 Making career decisions | |

| 5.8 Counseling for sports careers |

| Round 2 | Round 3 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domains | Content Elements | Mean | SD | Conv. | Cons. | CVR | Mean | SD | Conv. | Cons. | CVR |

| 1 | 1.1 | 4.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1 | 4.8 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1.2 | 3.3 | 1.03 | 1 | 0.43 | 0 | ||||||

| 1.3 | 4.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1 | 4.9 | 0.31 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 1.4 | 4.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 4.8 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 1.5 | 4.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1 | 4.7 | 0.47 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1 | |

| 2 | 2.1 | 4.7 | 0.47 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1 | 4.85 | 0.37 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 2.2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2.3 | 4.9 | 0.31 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4.95 | 0.22 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2.4 | 4.7 | 0.47 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1 | 4.9 | 0.31 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2.5 | 4.5 | 0.51 | 0.5 | 0.78 | 1 | 4.55 | 0.51 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1 | |

| 2.6 | 4.1 | 0.72 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.6 | 4.7 | 0.47 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1 | |

| 2.7 | 4.4 | 0.94 | 1 | 0.6 | 0.4 | ||||||

| 3 | 3.1 | 4.5 | 0.51 | 0.5 | 0.78 | 1 | 4.5 | 0.51 | 0.5 | 0.78 | 1 |

| 3.2 | 4.6 | 0.68 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 4.8 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 3.3 | 4.8 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4.8 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 3.4 | 4.3 | 0.66 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.8 | 4.55 | 0.51 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1 | |

| 3.5 | 4.5 | 0.69 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 4.55 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.9 | |

| 3.6 | 3.9 | 1.07 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.2 | ||||||

| 4 | 4.1 | 4.8 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4.8 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 4.2 | 4.7 | 0.47 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1 | 4.8 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 4.3 | 4.6 | 0.68 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 4.8 | 0.44 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 4.4 | 4.3 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.78 | 0.6 | 4.8 | 0.47 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 4.5 | 4.4 | 0.68 | 0.5 | 0.78 | 0.8 | 4.55 | 0.51 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1 | |

| 4.6 | 4.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1 | 4.65 | 0.49 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1 | |

| 4.7 | 4.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1 | 4.8 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 5 | 5.1 | 4.4 | 0.68 | 0.5 | 0.78 | 0.8 | 4.55 | 0.51 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1 |

| 5.2 | 4.8 | 0.62 | 0 | 1 | 0.8 | 4.9 | 0.31 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 5.3 | 4.6 | 0.68 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 4.7 | 0.47 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1 | |

| 5.4 | 4.7 | 0.66 | 0 | 1 | 0.8 | 4.8 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 5.5 | 4.4 | 0.82 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 4.5 | 0.69 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.8 | |

| 5.6 | 4.9 | 0.31 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4.9 | 0.31 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 5.7 | 4.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 1 | 4.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1 | |

| 5.8 | 4.9 | 0.31 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4.9 | 0.31 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

You, J.; Kim, W.; Lee, H.-S.; Kwon, M. Best Content Standards in Sports Career Education for Adolescents: A Delphi Survey of Korean Professional Views. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6566. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126566

You J, Kim W, Lee H-S, Kwon M. Best Content Standards in Sports Career Education for Adolescents: A Delphi Survey of Korean Professional Views. Sustainability. 2021; 13(12):6566. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126566

Chicago/Turabian StyleYou, Jeongae, Woosuk Kim, Hyun-Suk Lee, and Minjung Kwon. 2021. "Best Content Standards in Sports Career Education for Adolescents: A Delphi Survey of Korean Professional Views" Sustainability 13, no. 12: 6566. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126566

APA StyleYou, J., Kim, W., Lee, H.-S., & Kwon, M. (2021). Best Content Standards in Sports Career Education for Adolescents: A Delphi Survey of Korean Professional Views. Sustainability, 13(12), 6566. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126566