Evaluation of Livelihood Sustainability in the Context of Natural Forest Land Degradation Vulnerability: A Case Study of Five Counties in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

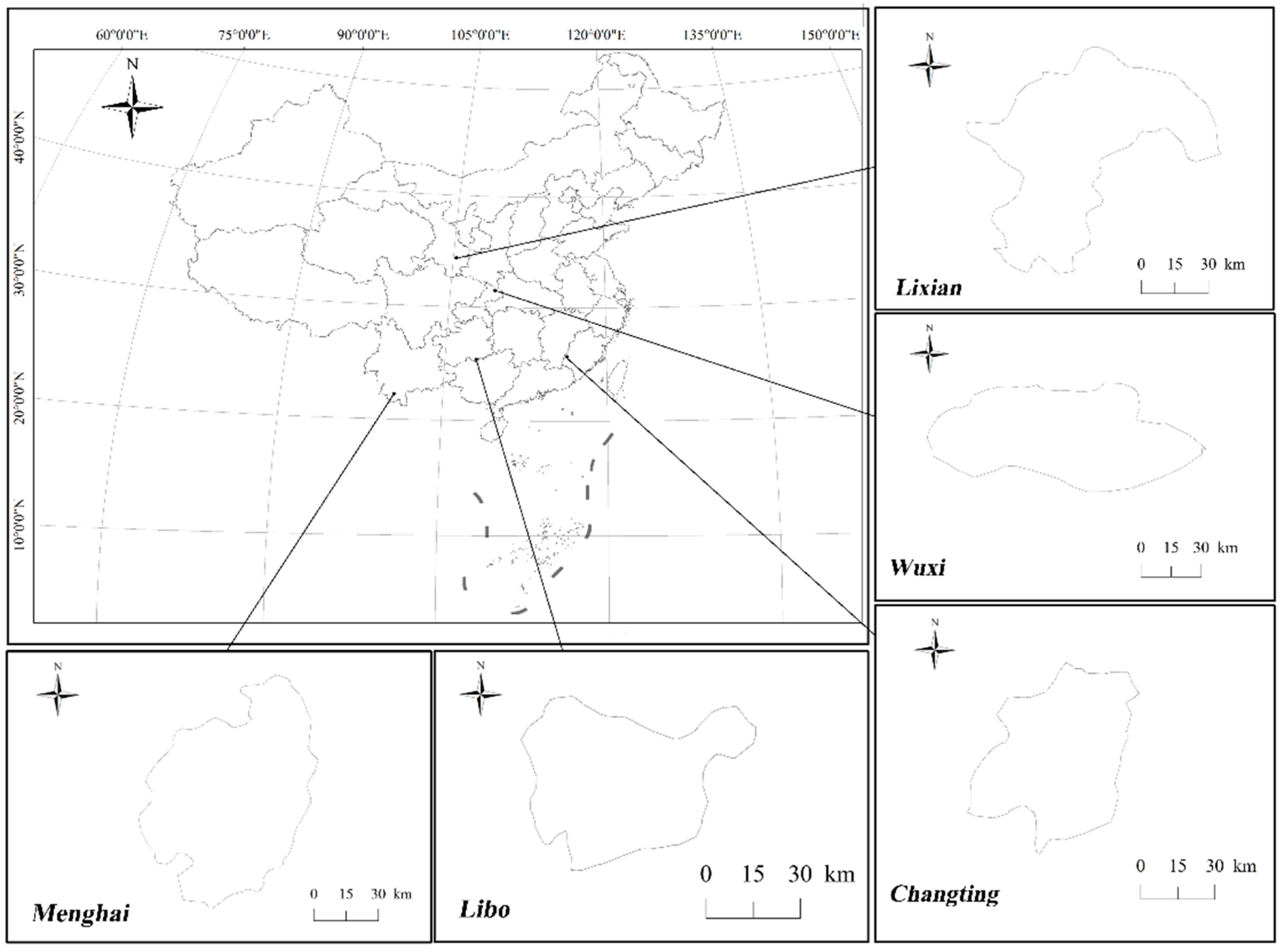

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Analysis Framework

2.3.1. Construction of the Livelihood Sustainability Index

2.3.2. Entropy Method

3. Results

3.1. Livelihood Assets

3.1.1. Human Assets

3.1.2. Natural Assets

3.1.3. Physical Assets

3.1.4. Financial Assets

3.1.5. Social Assets

3.2. Livelihood Strategies

3.2.1. Diversification of Livelihoods

3.2.2. Off-Farm/Forestry Activities

3.3. Sustainability Engagement Index

3.4. Comprehensive Livelihood Sustainability Index

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Policy Recommendation

5.2. Contribution to the Literature

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, J.; Liu, Y. Determination of land degradation causes in Tongyu County, northeast China via land cover change detection. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2010, 12, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CCICCD. China Final National Report of the Voluntary Land Degradation Neutrality (LDN) Target Setting Programme; China National Committee to Implement the UNCCD: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNCCD. Forests and Trees: At the Heart of Land Degradation Neutrality; UNCCD: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Scherr, S.J.; Yadav, S.N. Land Degradation in the Developing World: Implications for Food, Agriculture, and the Environment to 2020; Vision Discussion Papers; International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Z.G.; Dent, D. Recent land degradation and improvement in China. Ambio 2009, 38, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Li, Z. Economics of Land Degradation in China; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Li, X.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, D.; Yu, Z. Land resource degradation in China: Analysis of status, trends and strategy. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2010, 13, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, L. Land Degradation in China: Its Extent and Impact; UNCCD: Bonn, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yuexian, Y. Impacts and Effectiveness of Logging Bans in Natural Forests: People’s Republic of China; FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific: Bangkok, Thailand, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H. China’s natural forest protection program: Progress and impacts. For. Chron. 2017, 93, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- NFGA. Forest Resources in China: The 9th National Forest Inventory; National Forestry and Grassland Administration: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mullan, K.; Kontoleon, A.; Swanson, T.; Zhang, S. Evaluation of the impact of the natural forest protection program on rural household livelihoods. Environ. Manag. 2010, 45, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Ying, H. Research on the impact of financial input of natural forest protection project on the development level of people’s livelihood in forest areas. Issues For. Econ. 2020, 40, 595–601. [Google Scholar]

- Chunguang, S.; Zhenfeng, Z.; Lirong, C. Connotation, characteristics and development of natural forest protection public welfare undertakings in the new period. Issues For. Econ. 2021, 41, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bayrak, M.; Marafa, L. Livelihood implications and perceptions of large scale investment in natural resources for conservation and carbon sequestration: Empirical evidence from REDD+ in Vietnam. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tun, K.K.K.; Shrestha, R.P.; Datta, A. Assessment of land degradation and its impact on crop production in the dry zone of Myanmar. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2015, 22, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyssen, J.; Frankl, A.; Zenebe, A.; Deckers, J.; Poesen, J. Land management in the northern Ethiopian highlands: Local and global perspectives; past, present and future. Land Degrad. Dev. 2015, 26, 759–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Htwe, T.N.; Brinkmann, K.; Buerkert, A. Spatio-temporal assessment of soil erosion risk in different agricultural zones of the Inle Lake region, southern Shan State, Myanmar. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015, 187, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Kush, J.; Xu, Y.; Xu, L. Assessment of sustainable livelihoods of different farmers in hilly red soil erosion areas of southern China. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 64, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zha, X.; Bai, Y.; Wang, L. Evaluation of soil erosion vulnerability on the basis of exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity: A case study in the Zhuxi watershed, Changting, Fujian Province, southern China. Catena 2019, 177, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, G.M. Livelihood cycle and vulnerability of rural households to climate change and hazards in Bangladesh. Environ. Manag. 2017, 59, 777–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, M.; Wu, M.; Alam, G.; Shouse, R. Livelihood vulnerability of riverine-island dwellers in the face of natural disasters in Bangladesh. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xueyan, Z. Sustainable livelihoods research from the perspective of geography: The present status, questions and priority areas. Geogr. Res. 2017, 36, 1859–1872. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, G.M.; Pollard, L.; Mwenda, M.D. Perceptions of land-degradation, forest restoration and fire management: A case study from Malawi. Land Degrad. Dev. 2010, 21, 546–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, K. Risk assessment of forest landscape degradation using bayesian network modeling in the Miyun reservoir catchment (China) with emphasis on the Beijing-Tianjin sandstorm source control program. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 3876–3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teka, K.; Haftu, M.; Ostwald, M.; Cederberg, C. Can integrated watershed management reduce soil erosion and improve livelihoods? A study from northern Ethiopia. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2020, 8, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hella, J.P.; van Huylenbroeck, G.; Mlambiti, M.E. Small farmers’ adaptive efforts to rainfall variability and soil erosion problem in semiarid Tanzania. J. Sustain. Agric. 2003, 22, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Akter, S. Determinants of livelihood choices: An empirical analysis from rural Bangladesh. J. South Asian Dev. 2014, 9, 287–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DFID. Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets; Department for International Development: London, UK, 1999; p. 445. [Google Scholar]

- WCFB. The 9th Second-Type Inventory of Forest Resources in Wuxi; Wuxi County Forestry Bureau: Wuxi, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Fan, J.; Liang, B.; Zhang, L. Evaluation of sustainable livelihoods in the context of disaster vulnerability: A case study of Shenzha County in Tibet, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, J.; Wu, Y. Livelihood diversification and cropland use pattern in agro-pastoral mountainous region of eastern Tibetan plateau. J. Geogr. Sci. 2008, 18, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Nijkamp, P.; Xie, X.; Liu, J. A new livelihood sustainability index for rural revitalization assessment: A modelling study on smart tourism specialization in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Z.; Hongmei, L.; Pei, L. Impact of livelihood capital on the choice of livelihood strategy for resettled farmers: Based on the survey of resettled farmers in Hunan province. Econ. Geogr. 2020, 40, 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Nazari, S.; Rad, G.P.; Sedighi, H.; Azadi, H. Vulnerability of wheat farmers: Toward a conceptual framework. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 52, 517–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawei, X. Research on sustainable livelihoods of relocate migrants based on poverty alleviation. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2020, 34, 66–71. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C.E.; Weaver, W. The Mathematical Theory of Communication; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Tian, D.; Yan, F. Effectiveness of entropy weight method in decision-making. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 3564835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, M.M.G.T.; Kawasaki, A. Socioeconomic vulnerability to disaster risk: A case study of flood and drought impact in a rural Sri Lankan community. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 152, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.L.; Liu, S.Q.; Peng, L.; Wang, H.M. The impact of severe natural disasters on the livelihoods of farmers in mountainous areas: A case study of Qingping Township, Mianzhu City. Nat. Hazards 2014, 73, 1679–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.B.; Dietz, T.; Yang, W.; Zhang, J.D.; Liu, J.G. Changes in human well-being and rural livelihoods under natural disasters. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 151, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.P.; Yang, X.T.; Fang, Y.P.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, F.B. Impacts of snow disaster on rural livelihoods in southern Tibet-Qinghai plateau. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 31, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B.; Hochard, J.P. Land degradation and poverty. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jendoubi, D.; Hossain, M.S.; Giger, M.; Tomicevic-Dubljevic, J.; Ouessar, M.; Liniger, H.; Speranza, C.I. Local livelihoods and land users’ perceptions of land degradation in northwest Tunisia. Environ. Dev. 2020, 33, 100507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C.; Pang, W.; Hong, J. Impact of a regional payment for ecosystem service program on the livelihoods of different rural households. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 1058–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Wang, T.; Xia, X.L.; Chen, Y.Z.; Lv, H.Q.; Li, N. Analysis on the choice of livelihood strategy for peasant households renting out farmland: Evidence from western poverty-stricken areas in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liang, Y.C.; Li, S.Z.; Feldman, M.W.; Daily, G.C. Does household composition matter? The impact of the grain for green program on rural livelihoods in China. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 75, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.L. Agglomeration and radiation effect of the pull of urbanization. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2003, 13, 224–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.D.; Zhang, J.F.; Xie, F.T.; Liu, S.Q.; Cao, M.T.; Liu, E.L. Influential factors in employment location selection based on “push-pull” migration theory-a case study in three gorges reservoir area in China. J. Mt. Sci. 2015, 12, 1562–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. China Yearbook of Household Survey in 2019; National Bureau of Statistics: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gharibvand, H.K.; Azadi, H.; Witlox, F. Exploring appropriate livelihood alternatives for sustainable rangeland management. Rangel. J. 2015, 37, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shunji, O.; Kadirbyek, D. Recovery from a winter disaster in Tov Province of Mongolia. J. Arid Environ. 2017, 139, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hoq, M.S.; Raha, S.K.; Hossain, M.I. Livelihood vulnerability to flood hazard: Understanding from the flood-prone haor ecosystem of Bangladesh. Environ. Manag. 2021, 67, 532–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thao, N.T.T.; Khoi, D.N.; Xuan, T.T.; Tychon, B. Assessment of livelihood vulnerability to drought: A case study in Dak nong Province, Vietnam. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2019, 10, 604–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keshavarz, M.; Maleksaeidi, H.; Karami, E. Livelihood vulnerability to drought: A case of rural Iran. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 21, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.J.; Robinson, B.E.; Zheng, H.; Li, C.; Wang, F.C.; Li, R.N. Telecoupled sustainable livelihoods in an era of rural-urban dynamics: The case of China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Toufique, K.A.; Islam, A. Assessing risks from climate variability and change for disaster-prone zones in Bangladesh. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2014, 10, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, W.; Azeiteiro, U.; Alves, F.; Pace, P.; Mifsud, M.; Brandli, L.; Caeiro, S.S.; Disterheft, A. Reinvigorating the sustainable development research agenda: The role of the sustainable development goals (SDG). Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2018, 25, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Griggs, D.; Stafford-Smith, M.; Gaffney, O.; Rockstrom, J.; Ohman, M.C.; Shyamsundar, P.; Steffen, W.; Glaser, G.; Kanie, N.; Noble, I. Sustainable development goals for people and planet. Nature 2013, 495, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| County | Changting | Libo | Lixian | Menghai | Wuxi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coordinates | 34°19′ N 105°18′ E | 25°8′ N 107°57′ E | 25°40′ N 116°20′ E | 21°96′ N 100°45′ E | 31°29′ N 109°21′ E |

| Province (municipality) | Fujian | Guizhou | Gansu | Yunnan | Chongqing |

| Area (km2) | 3099 | 2432 | 4299 | 5368 | 4030 |

| Population (thousand) | 530 | 180 | 537 | 329 | 543 |

| Climate condition | Subtropical Monsoon Climate | Subtropical Monsoon Climate | Temperate Continental Monsoon Climate | Tropical Monsoon Climate | Subtropical Monsoon Climate |

| Major Components | Sub-Components | Proxy Indicator | Description of Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Livelihood assets (E1) | Human asset (0.0509) | Household labor force ratio (0.0052) [32,34] | Total labor force population/total household population |

| Labor education (0.0079) [34] | Below primary school = 0; primary school = 1; junior high school = 2; high school = 3; college and above = 4 | ||

| Labor skill training (0.0379) [34] | Not trained = 0; trained with no effects = 1; trained with a little effects = 2; trained with great effects = 3 | ||

| Natural asset (0.2260) | Household farmland area (0.0824) [34] | (Mu) | |

| Household woodland area (0.1336) [35] | (Mu) | ||

| Access to water (0.0100) [34,36] | Insufficient and inconvenient = 0; either sufficient or convenient = 1; sufficient and convenient = 2; | ||

| Physical asset (0.0224) | Household equipment assets (0.0140) [32] | No = 0; 1 motorcycle = 1; 1 car/tractor = 2; 1 truck = 3 | |

| Housing condition (0.0083) [34] | No houses = 0; rented house = 1; one-story house = 2; multi-story house = 3 | ||

| Financial asset (0.1950) | Difficulty in borrowing (0.1018) [34] | Numbers of borrowing channels | |

| Difficulty in loaning (0.0567) [34] | Difficult = 0; general = 1; easy = 2 | ||

| Family savings (0.0365) [34] | No = 0; a small amount = 1; a large amount = 2 | ||

| Social asset (0.1171) | Connection to local cooperatives (0.0933) [37] | No such organizations here = 0; have such organizations but not willing to join = 1; joined = 2; | |

| Social network support (0.0238) [34] | No assigned cadres = 0; yes but no effects = 1; yes with a little effects = 2; yes with great effects = 3 | ||

| Livelihood strategies (E2) | Diversification of livelihoods (0.0381) | Number of livelihood activities (0.0381) [32,34] | |

| Off-farm/forestry activities (0.0158) | Ratio of employment irrelevant with traditional agricultural and forestry activities to all (0.0158) [32] | ||

| Sustainability engagement (E3) | Participation in natural forest protection (0.1407) | Times of participation in natural forest conservation projects as forestry rangers (0.1407) | |

| Sustainable forestry-related activities (0.1939) | Ratio of sustainable forestry-related activities to all (0.1939) |

| Location | Human Assets | Natural Assets | Physical Assets | Financial Assets | Social Assets | Livelihood Assets |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changting | 0.4580 | 0.2255 | 0.6838 | 0.3489 | 0.2623 | 1.9785 |

| Libo | 0.4690 | 0.1036 | 0.5833 | 0.2257 | 0.2937 | 1.6753 |

| Lixian | 0.5397 | 0.1771 | 0.4099 | 0.1902 | 0.3272 | 1.6442 |

| Menghai | 0.2506 | 0.2617 | 0.5180 | 0.2636 | 0.3366 | 1.6304 |

| Wuxi | 0.5569 | 0.0673 | 0.4356 | 0.2265 | 0.2096 | 1.4958 |

| Average | 0.4548 | 0.1670 | 0.5261 | 0.2510 | 0.2859 | 1.6849 |

| Location | Labor Force Ratio | Education | Training | Human Assets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changting | 0.5910 | 2.8000 | 1.6667 | 0.4580 |

| Libo | 0.5780 | 3.2500 | 1.3281 | 0.4690 |

| Lixian | 0.5064 | 2.5000 | 1.5800 | 0.5397 |

| Menghai | 0.6483 | 1.6071 | 0.7143 | 0.2506 |

| Wuxi | 0.5738 | 2.8859 | 1.5369 | 0.5569 |

| Average | 0.5795 | 2.6086 | 1.3652 | 0.4548 |

| Location | Farmland | Woodland | Access to Water | Natural Assets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changting | 7.5497 | 10.5133 | 1.7000 | 0.2255 |

| Libo | 9.9214 | 9.1655 | 1.6250 | 0.1036 |

| Lixian | 8.0240 | 2.6500 | 1.5400 | 0.1771 |

| Menghai | 39.0571 | 17.8571 | 1.6429 | 0.2617 |

| Wuxi | 6.8104 | 13.8592 | 1.5101 | 0.0673 |

| Average | 14.2725 | 10.8090 | 1.6036 | 0.1670 |

| Location | Equipment | Housing Condition | Physical Assets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Changting | 1.5333 | 2.6333 | 0.6838 |

| Libo | 1.4375 | 2.4219 | 0.5833 |

| Lixian | 1.2600 | 2.4000 | 0.4099 |

| Menghai | 2.3929 | 2.2857 | 0.5180 |

| Wuxi | 1.4966 | 2.4362 | 0.4356 |

| Average | 1.6241 | 2.4354 | 0.5261 |

| Location | Difficulty in Borrowing | Difficulty in Loaning | Family Savings | Financial Assets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changting | 1.6333 | 0.9667 | 0.6667 | 0.3489 |

| Libo | 1.1719 | 0.4375 | 0.9219 | 0.2257 |

| Lixian | 1.2400 | 0.6400 | 0.5000 | 0.1902 |

| Menghai | 1.3571 | 0.3571 | 0.5357 | 0.2636 |

| Wuxi | 1.3154 | 0.5101 | 0.8322 | 0.2265 |

| Average | 1.3436 | 0.5823 | 0.6913 | 0.2510 |

| Location | Cooperatives | Social Network | Social Assets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Changting | 0.5333 | 2.6333 | 0.2623 |

| Libo | 0.4375 | 2.4219 | 0.2937 |

| Lixian | 0.2600 | 2.4000 | 0.3272 |

| Menghai | 1.3929 | 2.2857 | 0.3366 |

| Wuxi | 0.4966 | 2.4362 | 0.2096 |

| Average | 0.6241 | 2.4354 | 0.2859 |

| Location | Diversification of Livelihoods | Off-Farm/Forestry Activities | Livelihood Strategy Index |

|---|---|---|---|

| Changting | 0.1211 | 0.0529 | 0.1740 |

| Libo | 0.1440 | 0.1361 | 0.2801 |

| Lixian | 0.1220 | 0.0456 | 0.1676 |

| Menghai | 0.1991 | 0.0732 | 0.2723 |

| Wuxi | 0.0826 | 0.1430 | 0.2256 |

| Average | 0.1338 | 0.0901 | 0.2239 |

| Location | Participation in Natural Forest Protection | Sustainable Forestry-Related Activities | Sustainability Engagement Index |

|---|---|---|---|

| Changting | 0.0439 | 0.0208 | 0.0647 |

| Libo | 0.0393 | 0.0643 | 0.1036 |

| Lixian | 0.0667 | 0.0837 | 0.1505 |

| Menghai | 0.0693 | 0.0462 | 0.1155 |

| Wuxi | 0.0477 | 0.0259 | 0.0736 |

| Average | 0.0534 | 0.0482 | 0.1016 |

| Location | Livelihood Assets | Livelihood Strategies | Sustainability Engagement | Livelihood Sustainability Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changting | 1.9785 | 0.1740 | 0.0647 | 2.2171 |

| Libo | 1.6753 | 0.2801 | 0.1036 | 2.0590 |

| Lixian | 1.6442 | 0.1676 | 0.1505 | 1.9622 |

| Menghai | 1.6304 | 0.2723 | 0.1155 | 2.0182 |

| Wuxi | 1.4958 | 0.2256 | 0.0736 | 1.7950 |

| Average | 1.6849 | 0.2239 | 0.1016 | 2.0103 |

| Year | Migrant Labor Population (Million) | Ratio to Total Rural Population |

|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 277.47 | 45.98% |

| 2016 | 281.71 | 47.77% |

| 2017 | 286.52 | 49.69% |

| 2018 | 288.36 | 51.13% |

| 2019 | 290.77 | 52.71% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, Y.; He, C. Evaluation of Livelihood Sustainability in the Context of Natural Forest Land Degradation Vulnerability: A Case Study of Five Counties in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126580

Lin Y, He C. Evaluation of Livelihood Sustainability in the Context of Natural Forest Land Degradation Vulnerability: A Case Study of Five Counties in China. Sustainability. 2021; 13(12):6580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126580

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Yuguo, and Chao He. 2021. "Evaluation of Livelihood Sustainability in the Context of Natural Forest Land Degradation Vulnerability: A Case Study of Five Counties in China" Sustainability 13, no. 12: 6580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126580

APA StyleLin, Y., & He, C. (2021). Evaluation of Livelihood Sustainability in the Context of Natural Forest Land Degradation Vulnerability: A Case Study of Five Counties in China. Sustainability, 13(12), 6580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126580