Abstract

This paper, which is focused on evaluating the policies and institutional control of the Brantas River Basin, East Java, Indonesia, aims to review government regulations on watershed governance in Indonesia. A qualitative approach to content analysis is used to explain and layout government regulations regarding planning, implementation, coordination, monitoring, evaluation, and accountability of the central and local governments in managing the Brantas watershed, East Java, Indonesia. Nvivo 12 Plus software is used to map, analyze, and create data visualization to answer research questions. This study reveals that the management regulations of the Brantas watershed, East Java, Indonesia, are based on a centralized system, which places the central government as an actor who plays an essential role in the formulation, implementation, and accountability of the Brantas watershed management. In contrast, East Java Province’s regional government only plays a role in implementing and evaluating policies. The central government previously formulated the Brantas watershed. This research contributes to strengthening the management and institutional arrangement of the central government and local governments that support the realization of good governance of the Brantas watershed. Future research needs to apply a survey research approach that focuses on evaluating the capacity of the central government and local governments in supporting good management of the Brantas watershed.

1. Introduction

Institutional arrangements in the management of watersheds (DAS) in Indonesia are a challenge for the government. Watersheds (DAS) are strategic areas necessary for economic, social, cultural, and environmental conservation interests. The sustainability of social-ecological systems (SESs) depends in part upon the fit between institutions, the problems they are meant to address, and the contexts in which they operate [1].

Institutional research on integrated water resources management has been carried out in several countries. According to Chikozho, most countries (including Tanzania and South Africa) have initiated water sector reform programs that stress comprehensive river basin management based on integrated water resources management (IWRM) principles, user involvement in government, cost recovery, and sustainable resource use [2]. Integrated water resource management identifies critical factors for genuine stakeholder involvement in decision making at the basin level to make more relevant and useful policies. It focuses on conflict resolution as an important issue around which dialogue and negotiation platforms can revolve. Stakeholder participation in river basin management is depicted as a complex, sociopolitical process that must consider and reconcile a range of interests across sectors and users in the basin.

The institutional framework for water resources management in river basins consists of established rules, norms, practices, and organizations that provide a structure for human activities related to water management. In particular, established organizations are considered part of an institution [3]. For practical purposes, the overall institutional framework is felt in three broad categories: policy, legal, and administrative. According to Donie [4], the rules and regulations related to watershed management institutions on Batam Island were still overlapping. There was weak coordination between central agencies and local agencies [5].

As the paradigm shift from command-and-control statutes to collaborative partnerships increases, public administrators, policymakers, and watershed stakeholders will become more dependent on collaborative partnerships to solve complex environmental problems [6]. Through the model of watershed management in Indonesia that is delegated to the regions, there is a potential for the conflict of policies and the potential for the abuse of authority. As explained by Pambudi [5], this type of watershed management involves multistakeholders. This means that the role of policy is expected to be able to clarify the role of each stakeholder and create collaboration between stakeholders. This indicates that an integrated and comprehensive policy is needed to protect the environmental ecosystem of watershed areas [7,8]. Therefore, watershed management can be beneficial for the sustainability of the ecosystem and social community.

Previous studies on watershed governance were more directed and focused on environmental conservation aspects that were studied based on ecological perspectives, the role of communities, and sustainable development [7,8,9]. Research that focuses on aspects of organizational governance in the formulation, implementation, evaluation, and monitoring of watershed governance has not been widely carried out. In Indonesia, a very important aspect to ensure that watershed management can run according to the desired line is the regulatory aspect. In the framework of safeguarding, protecting and preserving water resources, there are regulations/laws/legislation which include legislation, government regulations, and presidential decrees. An alternative form of institution that is important for integrated watershed management is carried out by a team in the form of a DAS Council or Forum. The DAS Council is formed in several levels as follows: (1) National Scope (National DAS Council) which functions to determine policies, strategies, and programs for watershed management at the national level; (2) Regional Scope (Forum DAS Provinsi) which functions to determine policies, strategies, and programs for watershed management at the regional level; and (3) Local Scope (Forum DAS Daerah) which functions to determine policies, strategies, programs, implementation, and financing of watershed management at the watershed level or Regency/City. In general, the findings of this study confirm that the Indonesian government has not succeeded in realizing integrated, participatory, and collaborative management of the Brantas watershed due to the centralistic paradigm of watershed management. The regulations for the management of the Brantas watershed show that the management of the watershed has not been supported by institutional designs that support the well-functioning management of the Brantas watershed [10]. The overlapping roles of central government agencies and overlapping roles between the central and local governments in watershed management in planning, evaluating, and directing activities have resulted in sectoral conflicts between central government agencies towards watersheds in Indonesia. This research contributes to the formulation of government policies that support institutional arrangements, such as legal regulations governing watershed management; have a clear division of watershed management authority; and prioritize integrated, participatory, and collaborative watershed management mechanisms.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Institutional Fit Related to Environmental Issues

The institutional infrastructure, together with governance and leadership, greatly influences the capacity to manage complex systems. The two most significant factors for resource management are institutional arrangements and a more elevated awareness of the importance of more effective governance forms, as many cases indicate. The lack of institutional fit has frequently diminished service performance effectiveness [11] and other elements [12]. Hagedorn [13] introduced the concept of institutional fit that helped institutional analysts comprehend the complexity inherent in the human and environmental systems that sustain society. The study has also drawn vital consideration to the importance of adjusting environmental institutions to the problems they intend to address. Moreover, Young [14] revealed that institutional fit is closely associated with predicting analysis and with identifying the governance arrangements that might best address them. The concept of institutional fit is an essential pillar of research in the developing field of sustainability science. According to Cox [15], formalization can improve institutional fit. In this context, the concept of fit defines a form of expressing specific theoretical propositions that associate a set of variables to one other and the results.

The concept of institutional fit has been used to examine various governance problems, including environmental governance issues. Epstein et al. [1] reviewed the literature to classify three main types of institutional fit: ecological fit, social fit, and social-ecological system fit. The sustainability of social-ecological systems (SESs) depends in part upon the fit among institutions. To understand how institutions affect behavior and resolve ecological problems, research on social and environmental fit might improve. The means that an institution can adjust the environmental or social attributes of ecological issues. Lian and Lejano [16] conduct a critical analysis of China’s urbanization program and its implementation problems using a model of institutional fit. In future work, the concept of institutional fit should help to analyze difficulties attendant to a broad spectrum of development issues, such as the introduction of innovative technologies into rural areas and the mainstreaming of poverty alleviation programs. Uda et al. [17] examine the institutional fit of Indonesian regulations with peatland use and the characteristics of peatland users. A more profound comprehension of institutional fit, including technical, political, and cultural interactions between peatland regulations and peatland users’ practices in Indonesia, is essential. Indeed, the institutional fit assessment as a two-sided concept including rule makers and rule adopters provides further insights into improving policy implementation effectiveness.

2.2. Institutional Fit and Institutional Gap in the Water Resources and River Basin Governance

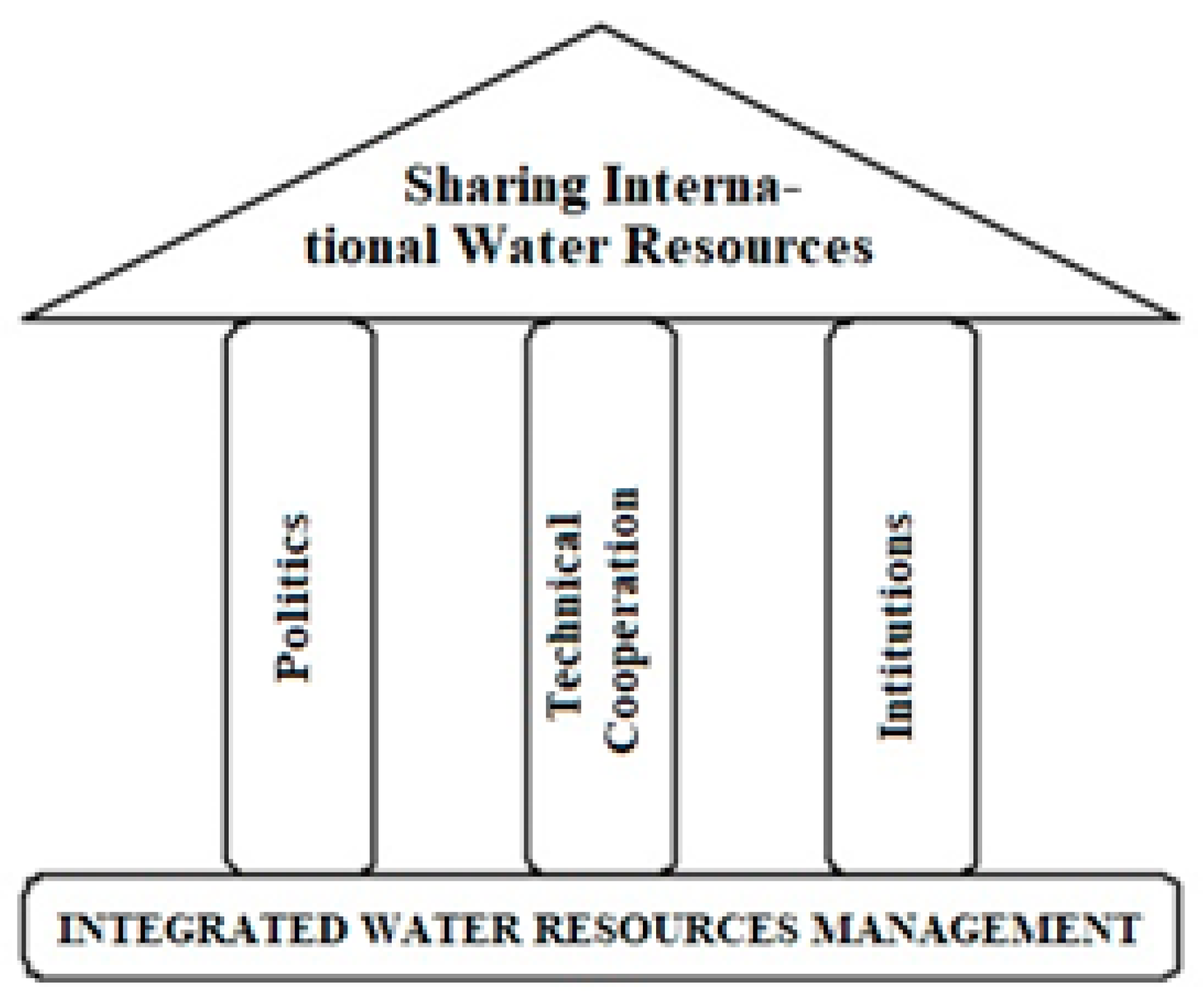

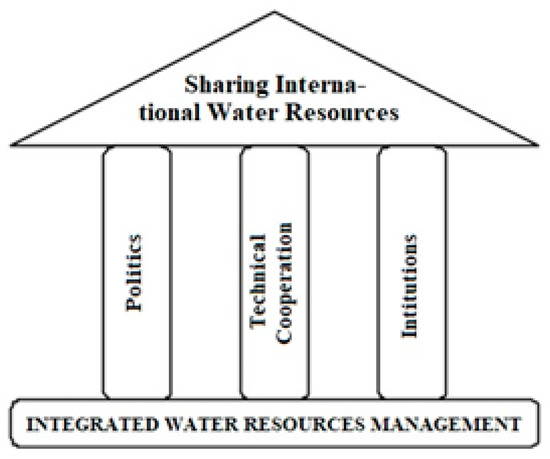

There is growing awareness that comprehensive and integrated water resources management is needed because: freshwater resources are limited; those limited freshwater resources are becoming increasingly polluted; limited freshwater resources have to be divided among the competing needs and demands in society; many citizens do not yet have access to sufficient and safe freshwater resources; techniques used to control water (such as dams and dikes) may often have unintended consequences for the environment; and there is a close relationship between groundwater and surface water, between coastal water and freshwater, etc. [18]. Integrated management of water resources is needed to reach the sustainable management of water resources. Integrated water resources management has been suggested as a strategy to improve water quality and increase water productivity in a river-basin context. Savenije and Van Der Zaag [19] proposed a classical temple for the distribution and management of international water resources (Figure 1). Integrated water resources management is the foundation, and the distribution of water resources is the temple roof in their model. The three pillars represent the necessary elements for sharing and managing international water resources: one political, one technical, and one institutional. The political pillar is required to implement an enabling environment, creating opportunities for international cooperation and planning. The legal, institutional post contains traditional and institutions instruments evolved at the national and international levels. In the frames of this pillar, the critical concern is the establishment of river basin organizations at the policy level and at the implementation level. For instance, a joint water commission may be established as the primary policy body. A river basin authority may be formed with responsibilities to execute, operate, and manage specific issues. Lastly, the technical or operational pillar must be in place, allowing for the broader concepts to be translated into active measures and actions. This pillar is regarded as central for the successful management of international river basins; if one of the outer pillars is weak or damaged, the technical post may bear most of the load.

Figure 1.

The classical temple of sharing international and river basin water resources [18,19].

Even though the model proposed by Savenije and Van Der Zaag [19] seems to be simple, there are difficulties in sustainable natural resource management. Integrated water resources management has created problems and controversies in both the developed and developing world. The issues have included incorporating natural territorial river basins with administrative organizations, combining land and water, and, more importantly, political participation and behavioral considerations in the planning process. In most developing countries, the controversies have included contestation of the rational technocentric approach by numerous social movements. The critical aspect that emphasizes partnerships among all those involved in the sustainable management of their water resources involves stakeholders integrating institutions for water resources management [20]. The concept of a River Basin Organization (RBO) is barely experienced in Asian countries, but an RBO is necessary to achieve effective integrated water resources management [21].

One exception that specifically designed an RBO is the Brantas basin in Indonesia, which has Jasa Tirta. In the Brantas case study, the aim was to evaluate how a single RBO could be developed and installed to cover multiple water uses in a developing country. Nevertheless, even as showpiece of donor initiatives in the region, Jasa Tirta is generally an endeavor that is primarily supported by government funds and interests. A close analysis of its function indicates no active stakeholder participation in its financing or its institutional arrangements. Jasa Tirta has not yet been able to see any other replication of itself anywhere else in the country, even in this practically useful parastatal form. The political economy of water sector reforms was much more problematic than dealing with solely irrigated agriculture because of the reduction of real interest among the local stakeholders and the multitude of vested interests. There is no Asian country that could ultimately succeed in establishing an adequate institutional framework that is required for integrated water resources management as prescribed [21].

The first step to initiating integrated water resources management is to develop a river basin integrated water resources management plan and then enact it into a formal procedure as a legal document. This document may guide all stakeholders related to program activities to the entire governmental framework so that it is possible to meet the integrated water resources management targets [22]. However, the complex relationships between all stakeholders’ formal and informal institutions in integrated water resources management need to be synchronized and may lead to an institutional gap. Indonesia has undertaken a step forward in implementing the integrated water resources management approach, namely the concept of such a comprehensive approach to improving water resources management towards achieving sustainable prosperity. The Indonesian government, under the coordination of the appropriate regulatory agencies, has issued the regulations on the water supply system, water groundwater, resources management, irrigation, water council, dam, water quality management, and pollution control, as well as the corporatization of water resources and financing required to implement the integrated water resources management approach, following the Law No. 7/2004. With all the problems and constraints that exist, new institutional arrangements must consider tradeoffs between the public administration authority and the river basin management authority. Still, in many cases, the programs are out of sync with each other [22].

As the number of resources continues to decline, while the need for water continues to increase, the Government of Indonesia has issued regulations to regulate water resource management. The central government gives authority to local governments to manage water resources for the benefit of the community or what is known as water use rights, as stipulated in Law No 7/2004 concerning water resources. Meanwhile, watershed management has been regulated in Government Regulation Number 37 of 2012 concerning watershed management. The regulation aims to realize the sustainability and harmony of the ecosystem for human life.

According to Ostrom [23], sustainable water resources management requires policies on a large scale. This scope means that with the tiered type of Indonesian government, water resources management will certainly involve cross-regional governments and many institutions. Consequently, clear regulations are needed [24]. Furthermore, institutions with interests in water management need to collaborate to solve the problem [25].

When such interactions are absent or regulations insufficient, disparity and incoherence might arise between institutions managing the same resource, potentially creating a challenge for sustainable natural resource governance [26,27]. Thus, Rahman et al. [27] intend the Inter-Institutional Gap (IIG) Framework as a recent approach to conceptualize the often-overlooked interconnectivity of different rule levels between formal and informal institutions in a resource system. This framework goes beyond the existing concepts of legal pluralism, institutional emptiness, structural loopholes, and cultural mismatch, each of which offers valuable insights into particular gaps between formal and informal institutions but do not adequately address the interaction at each level of rule.

2.3. Relevant Perspectives on the Institutional Fit of IWRM and River Basin

Institutions’ assets of rights, rules, and decision-making procedures form a fundamental part of environmental management. How well environmental institutions match spatial or temporal scales of ecosystems and account for functional ecosystem processes is termed the “problem of fit” [28]. Functional misfit contributes substantially to the deterioration of ecosystem services [26]. It concerns the failure of an institution or a set of institutions to take adequately into account the nature, functionality, and dynamics of the specific ecosystem it influences [28]. Achieving institutional fit is challenging, particularly for complex issues that span multiple societal sectors, which is common for sustainability issues [3]. Where such institutional gaps occur, it is essential to overcome them by creating channels for informed dialogue among stakeholders [29].

Watershed management is a multidimensional problem with physical, social, economic, and institutional components [30]. Therefore, the most fundamental aspect of institutional analysis in watershed waters is exploring the institution’s coordinating role [18]. Randhir and Raposa [31] also stated that sustainable development depends, in part, on the policy, institutional, and legal framework related to the environment as well as on the implementation capacity. Therefore, efforts to improve the implementation of environmental legislation and measures to strengthen the ability of ecological authorities should consider the political and institutional contexts.

The institutional framework for water resources management in a river basin context consists of established rules, norms, practices, and organizations that provide a structure to human actions related to water management. Notably, the established organizations are considered a subset of institutions [3]. For practical purposes, the overall institutional framework is felt in three broad categories: policies, laws, and administration, all of which are related in some way to water resources management in a river basin context.

Policies are related to national guidelines, local government policies, and organizational policies. Policies are also determined by many actors at federal, regional, or corporate levels [30]. Laws are related to ceremonial laws, procedures, informal rules, norms, practices, and internal rules of organizations. Usually, policies and regulations are interlinked at the sources, as well as at the implementation level. In some countries, a water policy has already been established, and they are in the process of formulating laws to implement them. The administration here means the organizations involved in water management and their internal rules. The method of control is not included. The organizations are necessary for two levels: resource management and delivery management [18].

According to Bandaragoda and Babel [21], the IWRM process in developing countries is part of the development package. It seems that the institutional model tends to impose on the complexity at hand. Reddy [32], in India, found that watershed management requires technology as a good and conducive policy. Meanwhile, from a legal standpoint, he did not find legislative support. Lebel et al. [33] emphasize the decision process among stakeholders in planning and decision making. Consequently, the legal enactment of regulations for conservation and administrative collaboration with nongovernment parties is also key. Meanwhile, Bhat et al. [34] emphasize area waste management, which is due to the lack of authority possessed by Jasa Tirta 1 as a manager of environmental problems. From several studies, an increasing number of institutions consisting of policy, law, and administration play an essential role in managing water resources, especially watersheds.

2.4. Institutional Collaboration Model for River Basin Sustainability

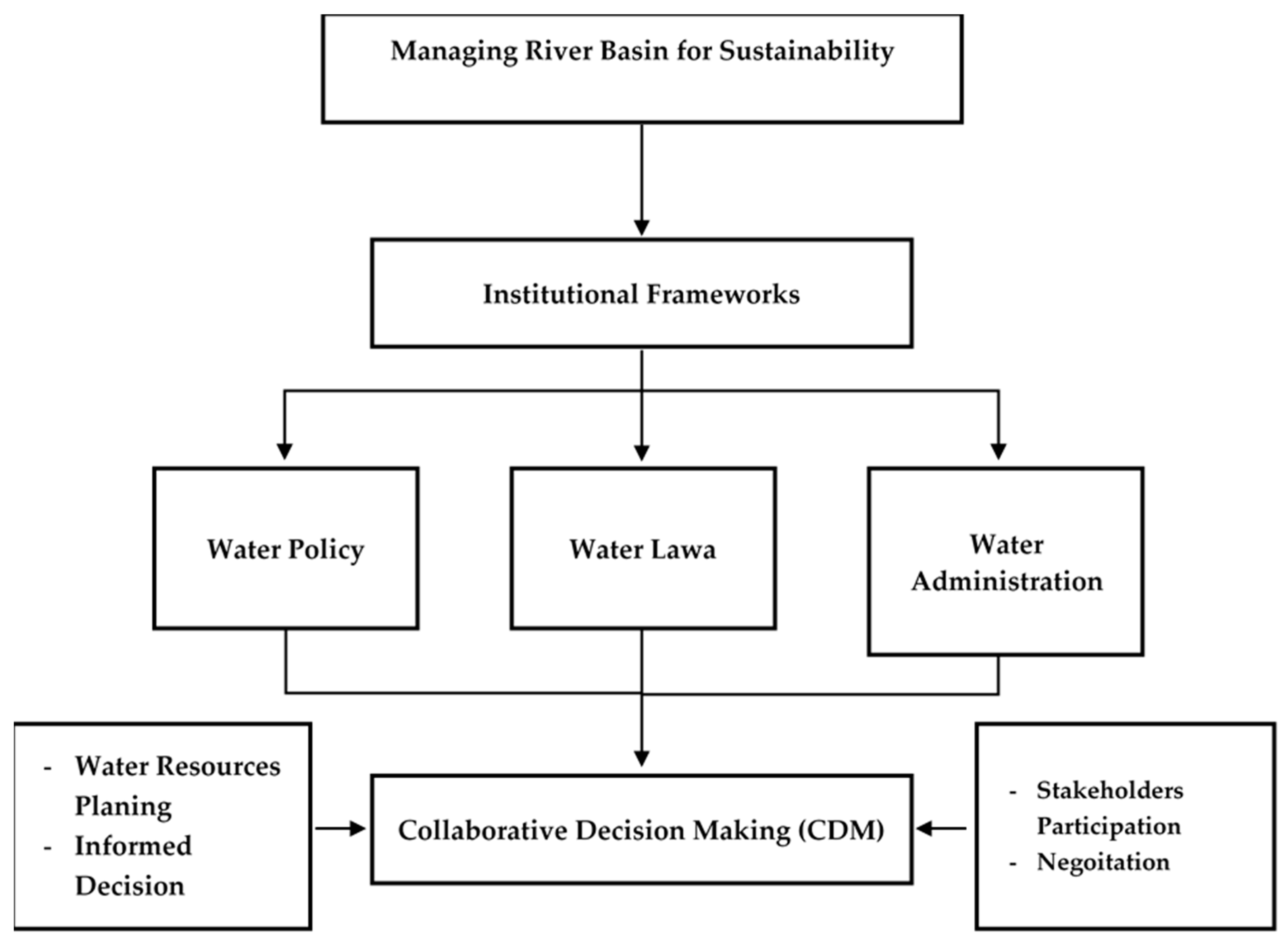

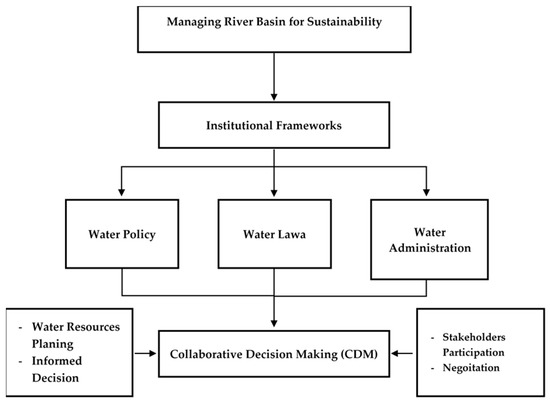

Collaboration in environmental management is a complex process because it involves all interests. Although each case has a different complexity crowd, often the process of building consensus between stakeholders is quite difficult because of the existing interests and perspectives. Thus, it requires proper collaborative management starting from who the actors are involved, size, problem significance, institutional setting, and focus of activities [25]. Based on previous research findings that show the existence of institutional gaps, an appropriate model is needed for sustainable river basin management. The proposed model of institutional collaboration partnerships for river basin sustainability (Figure 2) is developed based on the three pillars of the sustainable development model [35], the classical temple model of river basin water resources [18], and collaborative modeling for policy analysis in water resources management [36].

Figure 2.

Institutional collaboration model for managing river basin for sustainability.

The 2005 World Summit identified three main pillars of sustainability: environmental, economic, and social. Environmental aims to maintain a stable base of resources, preserve ecosystems, and biodiversity; to avoid overexploitation of renewable resources; to safeguard the quality of the atmosphere; to recycle, etc. Economic sustainability focuses on the generation of wealth in the long term, namely producing goods and services, creating jobs and prosperity, pursuing efficiency, etc. The social is concerned with achieving equity; providing social services; guaranteeing social inclusion; preserving cultures, groups, and places; and ensuring political accountability and community participation [35]. The institutional analysis is based on the institutional framework’s chosen definition and is related to three pillars of critical institutional areas: policies, laws, and administration.

Collaboration is an essential driver for the sustainable development of river basins related to economic, social, and environmental interests. Collaboration is also crucial for decision-making processes, requiring that decisions related to river basin management represent various stakeholders’ interests. There are interactions among three institutional components in terms of resources, social capacities, and the overall economy. For example, water law usually empowers water policy, and water policy, in turn, could initiate a process for new water law. The two components enrich each other. Together they define the structure for the functioning of water administration [18]. Collaborative modeling for policy analysis in water resources management rests on the integration of four key pillars: (i) water resources planning, (ii) informed decision making using computer-based models, (iii) stakeholder participation, and (iv) negotiation [36].

In general, there is an insufficient authority in river basin institutions to manage and coordinate larger integrated water resource management issues, including water quality and watershed management at the basin level, such as the findings in the Brantas River Basin [37]. Therefore, stakeholder cooperation in collaboration will lead to the increased importance of negotiation within the process. The interaction between the three institutional components and the association between the four main pillars of policy analysis for extraction are essential aspects of effective and sustainable water resource management.

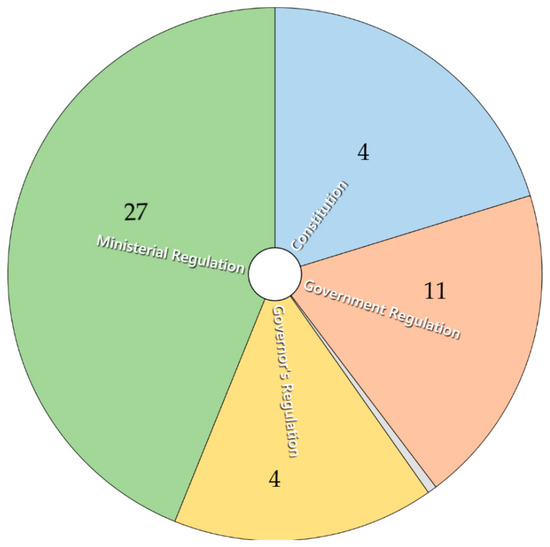

3. Method

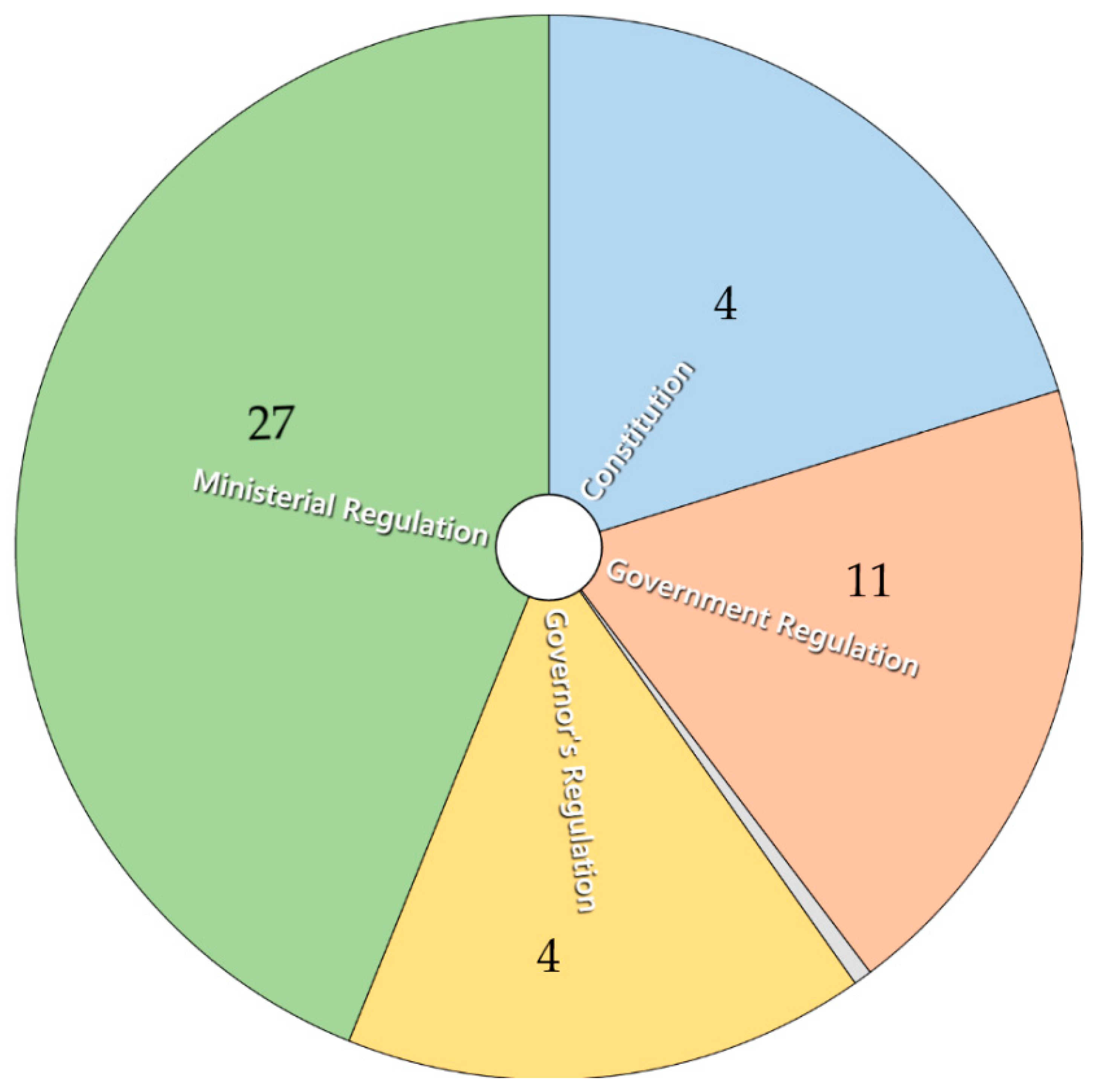

This study uses a qualitative content analysis approach to government regulations directly related to watershed management in Indonesia. Qualitative content analysis is a qualitative research approach used to understand and interpret the text in a document. The purpose of applying a qualitative approach to content analysis in this study is to understand and interpret the text of the laws and regulations governing watershed management in Indonesia. The total regulatory documents analyzed (Figure 3) in this study were 46 regulations concerning the Brantas River, including 4 constitutional documents, 11 government regulations, 27 ministerial decrees, and 4 governor regulations.

Figure 3.

Laws and regulations governing watershed management in Indonesia.

Analysis of the content of watershed management regulations in this study aims to answer research questions, namely how do government regulations regulate watershed management in Indonesia? What are the priority activities for watershed management in Indonesia? What is the watershed management model in Indonesia? What is the government’s role in watershed management in Indonesia? These research questions were answered using data on laws and regulations that specifically regulate watershed management in Indonesia.

The content analysis technique for watershed management regulations in this study uses the text coding technique developed by Strauss and Corbin, namely data categorization carried out in stages: determining research concepts, categorizing concepts, categorizing data or texts, and creating data clustering based on research concepts. The categorization and clustering of data carried out analyzed the linkage of data and research concepts, tested the link of data and research concepts, drew temporary research conclusions, re-examined provisional findings, and made arguments against interim results, which then become part of the research findings. As with the qualitative tradition of content analysis, this study’s data analysis process has a high degree of flexibility. The categorization of data carried out does not always refer to and is based on the research concepts and the direct examination of the data, which may reveal information not anticipated through the research concepts. Qualitative data analysis software (QDAS) is applied to simplify analyzing the content of watershed management regulations in this study. Nvivo 12 Plus software is used to help categorize, analyze, and visualize data. Data categorization with Nvivo 12 Plus was carried out through the following stages: (1) importing research data on the Nvivo 12 Plus work screen; (2) classification of research data based on the type of watershed management legislation being analyzed; (3) compiling research variables and indicators based on the research concept used; (4) coding data on watershed management regulations that are analyzed into collected variables and indicators; and (5) checking the validity of coding by reading and reinterpreting the coded text. The stages of data analysis using NVivo 12 Plus consisted of (1) analysis using the word frequency feature and the chart feature that produce priority data for watershed management and (2) analysis using the crosstab feature, which makes data models in the role of government in watershed management in Indonesia. Data visualization with Nvivo 12 Plus is displayed in a numeric percentage chart of data describing the answers to the research questions.

4. Result

4.1. Content of Watershed Management Regulation in Indonesia

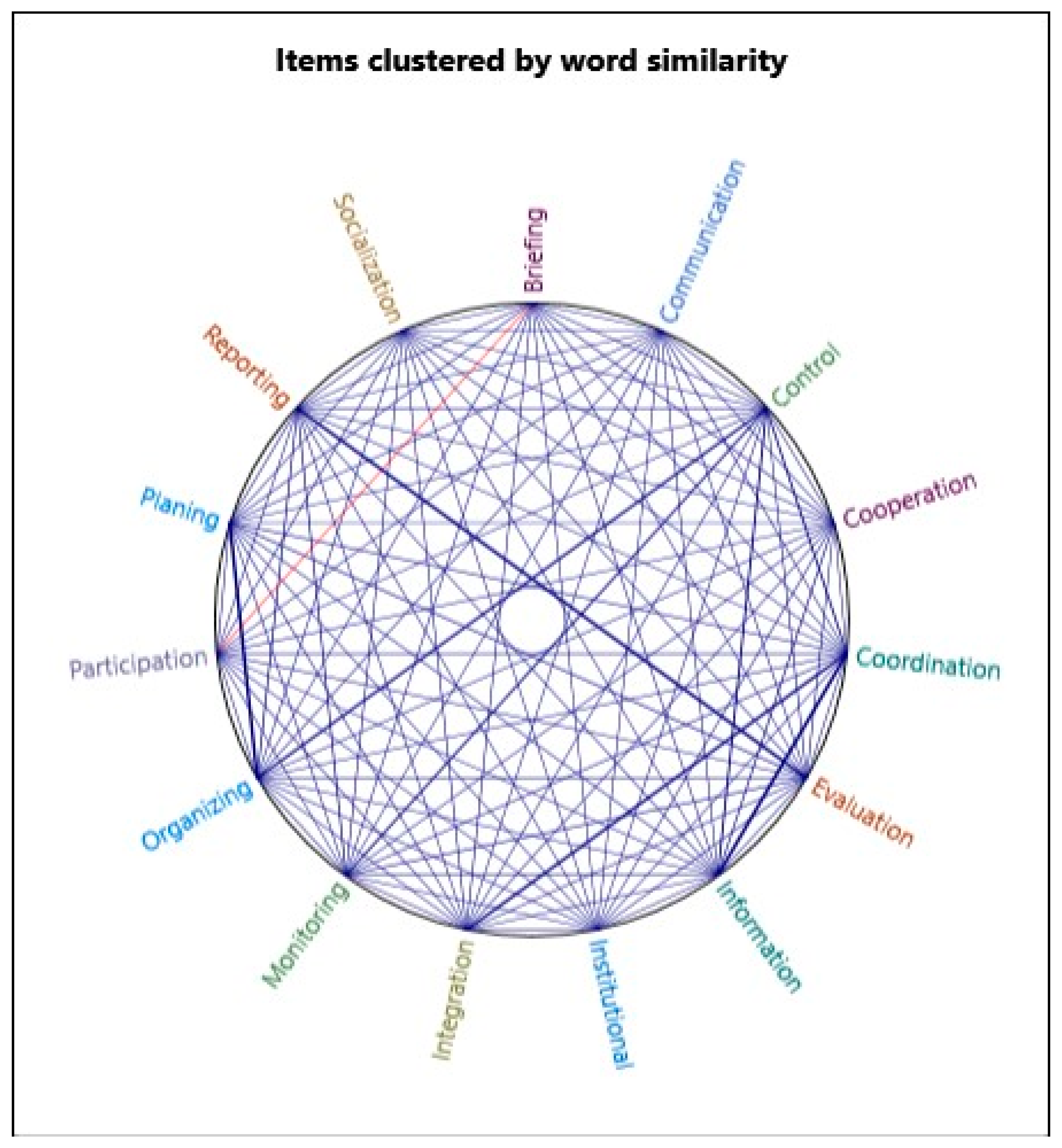

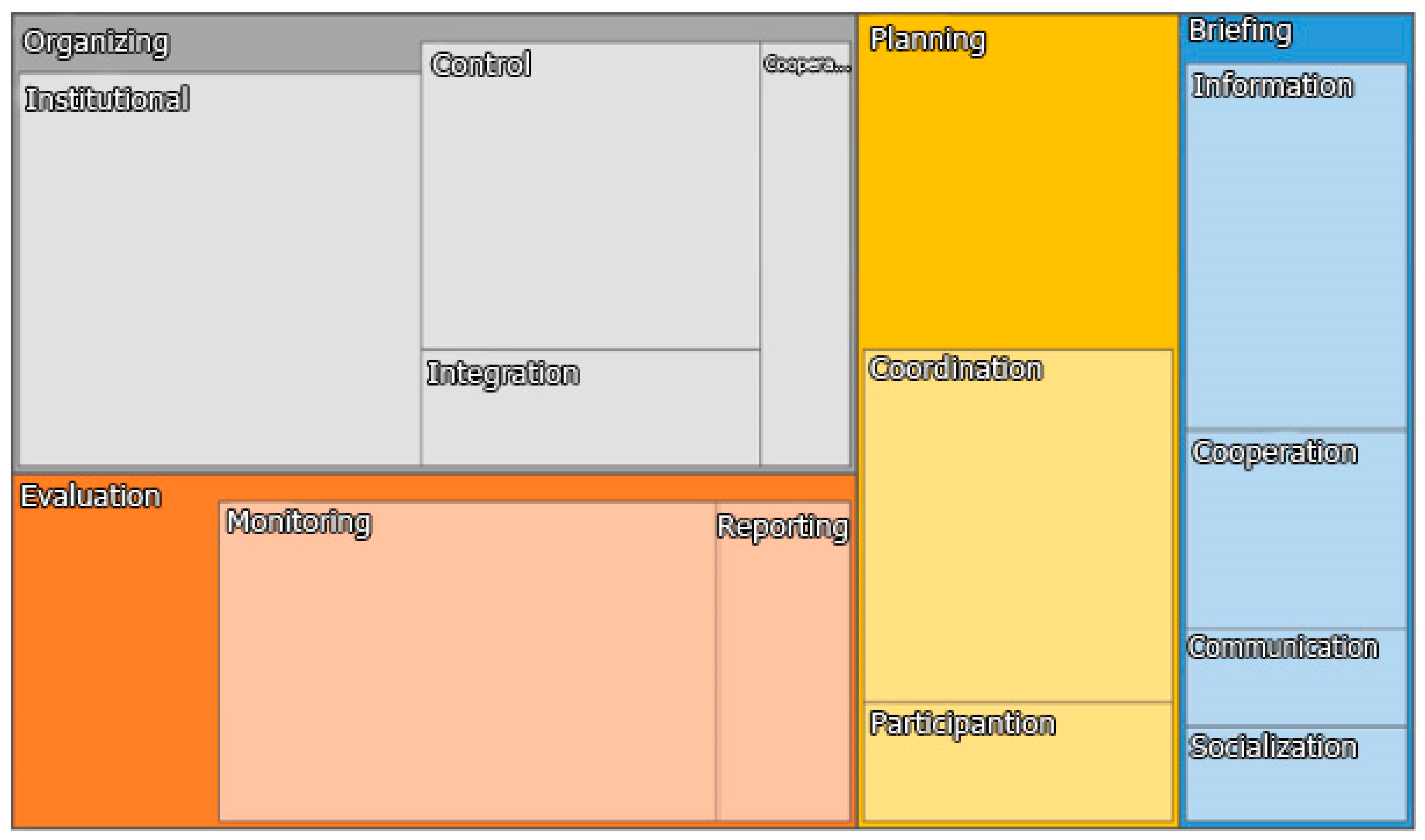

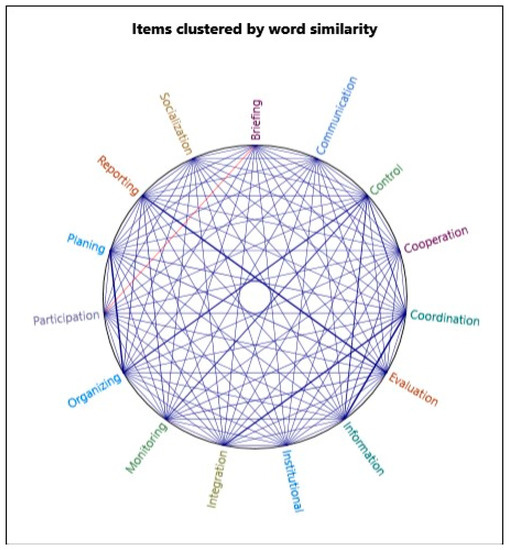

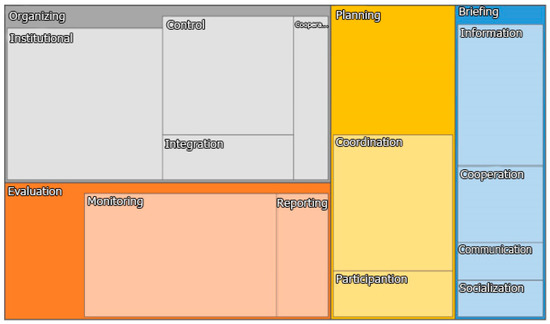

Figure 4 shows some important themes that are often encountered and directly related to Indonesia’s watershed management. The Indonesian government is trying to focus on watershed management from a management aspect. This is important considering that a watershed (DAS) is an arena where economic, social, cultural, and environmental conservation interests are intertwined, so a firm management model is needed from the government through many supporting regulations. Furthermore, to ensure that the management aspect runs well, it is necessary to strengthen the institutional part. Therefore, the function of monitoring coordination, planning, and implementation becomes the next focus. This indicates that implementing watershed regulations is determined by the synergy of many aspects that will make a set of regulatory policies in the watershed regulation less optimal if one of them is problematic.

Figure 4.

Analysis of the regulatory content of the Brantas watershed management in Indonesia.

Figure 5 reveals that there is a relationship between aspects of the Brantas river management in Indonesia as indicated by the Pearson correlation coefficient correlation value obtained from the coding results on the regulatory content regarding Brantas river governance. The Pearson correlation coefficient value scale is 0–1, where 0 indicates a weak correlation, while 1 indicates a strong correlation. Planning and organizing regulations have a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.8, which is the highest correlation value compared to planning correlations with other aspects. This value shows that planning activities are more related to resource organizing activities than participation activities and public coordination, which confirms that the Brantas river management system in Indonesia is more centrally oriented, placing local governments as actors who play a major role in organizing policies rather than formulating, monitoring, and evaluating policies. Policy organization has a strong correlation with supervision, which is 0.8, confirming that policy organization related to the activities of the central government overseeing the implementation of the Brantas river governance policy at the regional level. Reporting has a strong correlation with evaluation, namely 0.7. The strong correlation between reporting activities and evaluation activities confirms that the governance of the Brantas river in Indonesia is focused on the reporting and evaluation stages rather than the planning, direction, and policy dissemination stages.

Figure 5.

Analysis of the correlation of management regulations for the Brantas watershed in Indonesia.

Table 1 shows that the government prioritizes management aspects in watershed management regulations. The regulations issued aim to strengthen government capacity to control watershed management, starting from the planning, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation processes. As an authoritative agency in watershed management, the government can carry out management functions in coordination, supervision, and control activities. The management function is also further related to government mechanisms in controlling relations reciprocal between natural resources and humans and all their activities. The most crucial objective is to foster ecosystem sustainability and increase the benefit of natural resources for humans. A set of government regulations in watershed management relies on the synergy between sectors for conservation purposes. Therefore, this management is carried out to avoid conflicts and overlapping authority and policies in watershed management.

Table 1.

The percentage of content of Brantas watershed management regulations in Indonesia.

4.2. Watershed Management Regulatory Priorities

The watershed management priority for regulations issued by the government following Figure 6 is institutional/institutional arrangements. Strong institutions are an essential key in the success of watershed management regulations. The government needs to strengthen institutions with a robust legal framework and adequate authority to support monitoring, control, and evaluation functions. To be healthy, the government’s institutions must harmonize with related stakeholders’ aspirations and interests, especially local communities. Participation of the public and the private sector, for example, in the planning process and watershed management, will avoid conflict. Some conflicts, such as the conversion of the forest’s function around the watershed to residential development and industrial development, for example, has occurred due to the government’s inability to integrate all interests into one common consensus. This is also supported by inaccurate conflict resolution due to the government agencies’ lack of capacity, resulting in them being accused of having more probusiness interests. Therefore, government-formed institutions must have high persuasive abilities through appropriate leadership socialization and communication so that the sustainability of watershed management is maintained by relying on a sense of shared ownership between the government, local communities, and the private sector.

Figure 6.

A priority of watershed management regulations in Indonesia.

The coding of various watershed management regulations in Indonesia through NVIVO 12 Plus aims to reveal Indonesia’s watershed management priorities. The coding and analysis of watershed management priorities are carried out at various Indonesian regulation levels, ranging from laws, presidential regulations, presidential decrees, government regulations, ministerial regulations, government regulations, and governor decrees. Based on Figure 6, this analysis reveals that watershed management priorities in Indonesia include planning, organizing, evaluating, and briefing. The planning is carried out thought coordination and participation, and the organizing consists of institutional, control, integration, and cooperation. The evaluation carried out by monitoring and reporting and the briefing are conducted using the method of providing information, cooperation, communication, and socialization.

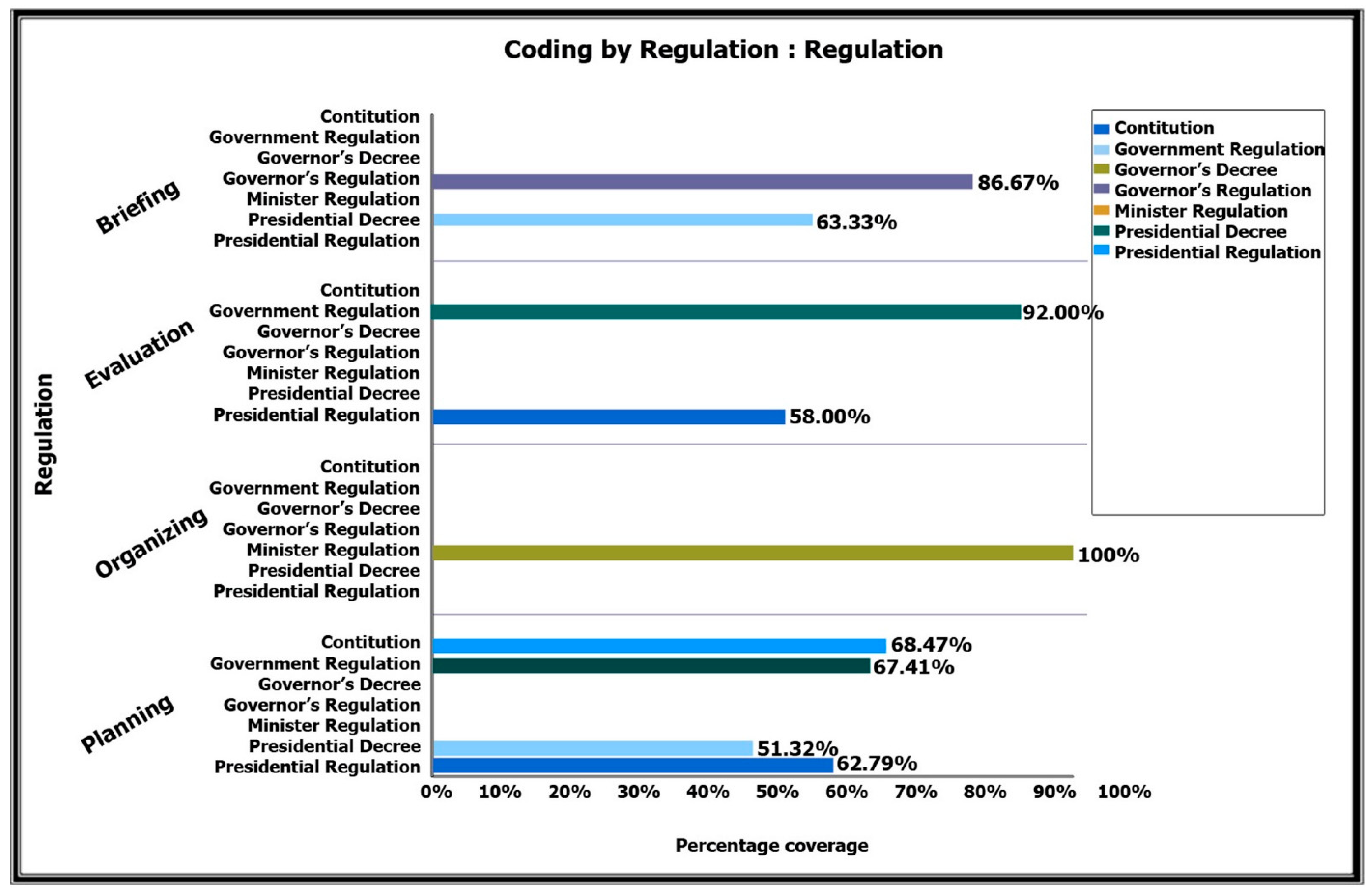

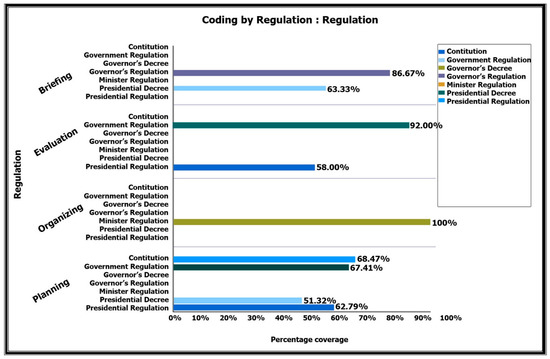

Based on Figure 7, Indonesia’s watershed management planning is contained in laws, presidential regulations, presidential decrees, and government regulations. Many watershed management plans are included in laws (68.47%), followed by government regulations (67.41%), presidential regulations (62%), and presidential decrees (51.32%). Organizing watershed management is concentrated in ministerial regulations (100%). The evaluation of watershed management is contained in two forms of law: government regulations (92%) and presidential regulations (58%). The direction of watershed management is regulated in governor regulations (86.67%) and presidential decrees (63.33%).

Figure 7.

A regulatory priority of watershed management in Indonesia is based on a regulatory level.

In Figure 7, the actors’ role in watershed management, based on the regulations in Indonesia, starting from the laws, presidential regulations, presidential decrees, government regulations, ministerial regulations, governor regulations, and governor decrees, is divided into four, namely planning, organizing, evaluating, and briefing. At the planning stage, the role of actors in watershed management was mostly played by the ministry of the public works housing profile (87.70%), followed by the management office watershed (86%), the general directorate (86%), the ministry of forest (62.36 %), and the ministry of the environment (54.01%). In the organizing stage, the actors’ role is concentrated in forest ministry (100%). The evaluation stage of the actors’ role was mostly played by the management office (90%) and general directorate (90%), then the ministry of forest (62.36%), the ministry of the environment (53.18%), and the ministry of the public works housing profile (96.82%). The government played the highest role of the actors in the briefing (86.67%), followed percentage the ministry of a public works housing profile (63.33%), the management office watershed (63%), and the general directorate (63%).

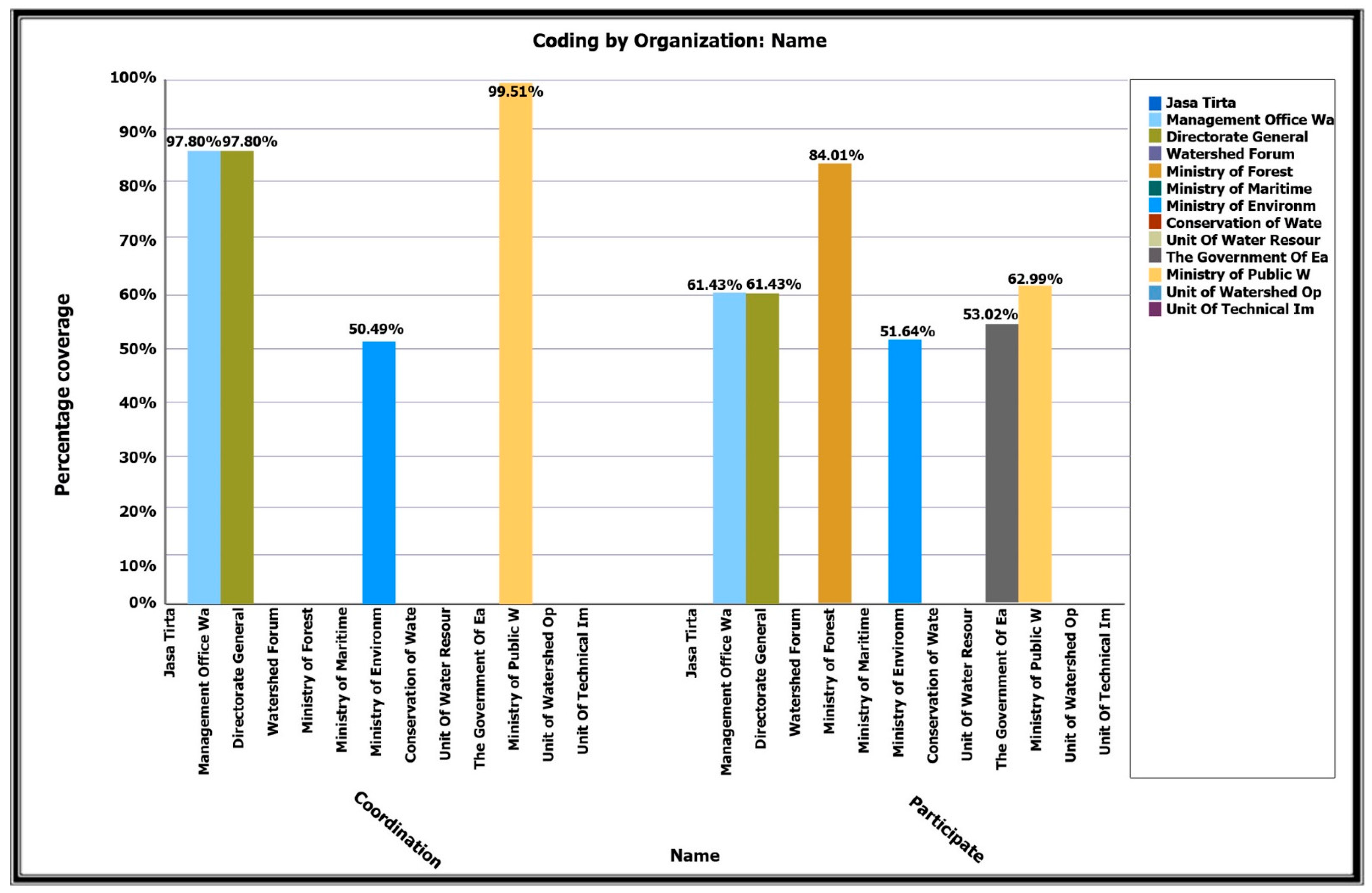

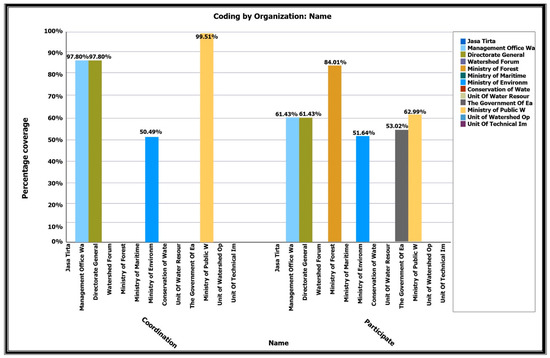

Based on Figure 8, the most coordinated planning for watershed management involves the ministry of a public works housing profile (99.51%), followed by the management office watershed (97%), the general directorate (97%), and the ministry of environment (50.49%). The ministry of forest is the most participating institution in watershed management planning (84.01%), followed by the ministry of a public watershed (62.99%), the management office watershed (61.43%), the general directorate (61.43%), the Government of East Java (53.02%), and the ministry of environment (51.64%).

Figure 8.

A priority of watershed management regulation in Indonesia based on the coordination and participate of institutions.

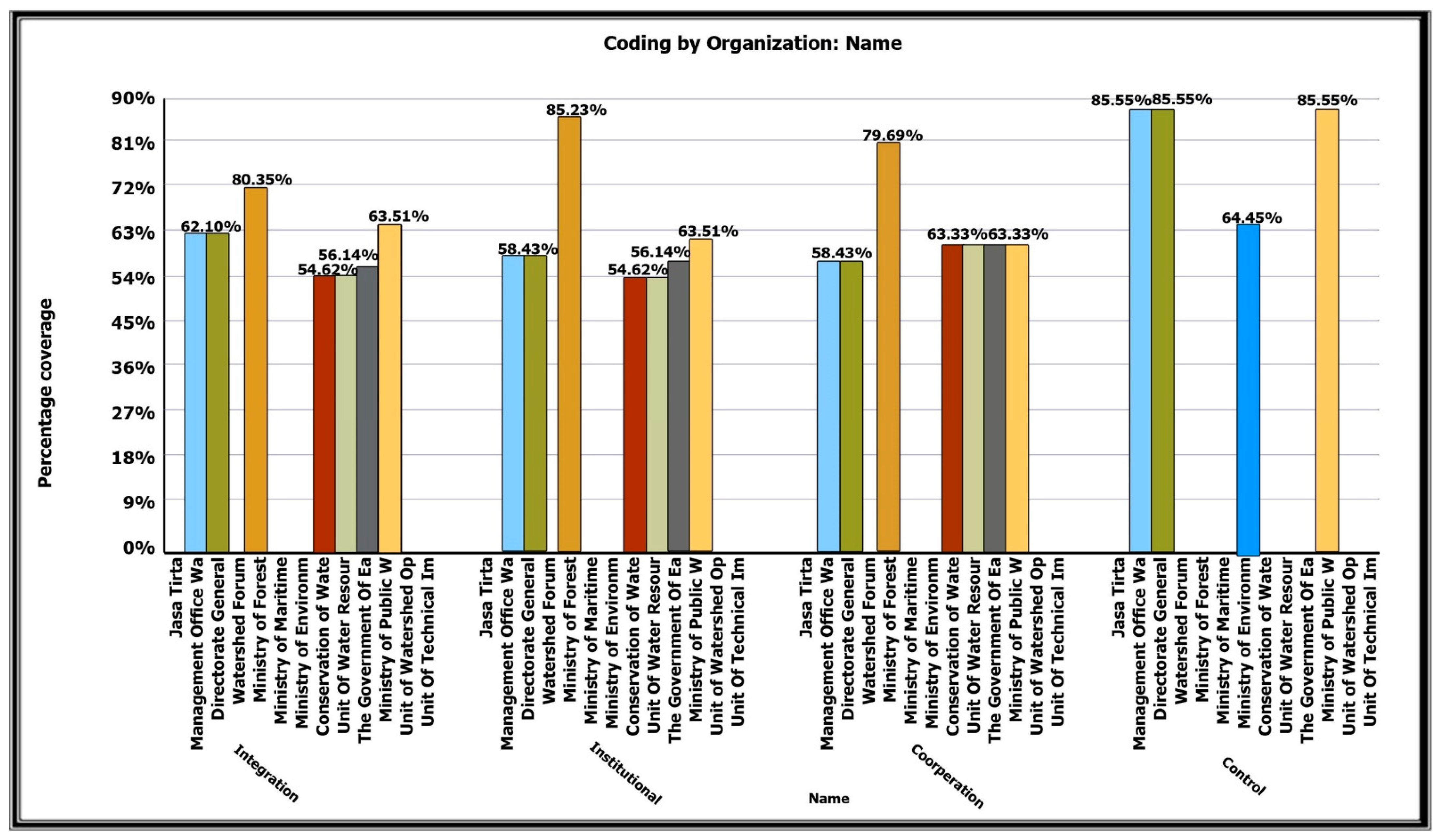

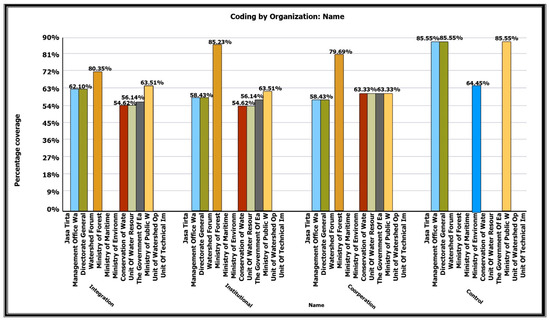

Figure 9 shows that watershed management’s organizing function is divided into four: integration, institutional, cooperation, and control. The ministry of forest mostly plays the Integration function (80.35%), followed by the ministry of a public works housing profile (63.51%), management office was (62.10%), general directorate (62.10%), the Government of East Java (56.14%), water conservation (54%) and unit of water resource (54%). The ministry of forest plays most institutional functions (85.23%), followed by ministry of a public works housing profile (59.79%), management office was (58.43%), general directorate (58.43%), the Government of East Java (56.68%), conservation of wale (54.39%) and the unit of water resources (54.39%). The cooperation function is mostly played by the ministry of forest (79.69%) followed by the conservation of wale (60.19%), the unit of water resource (60.19%), the Government of East Java (60.19%), the ministry of a public works housing profile (60.19%), management office (58.96%), and general directorate (58.96%). Three institutions dominate the control function, namely management office (85.55%), general directorate (85.55%), ministry of a public works housing profile (85.55%), and ministry of environment (64.45%).

Figure 9.

A priority of watershed management regulation in Indonesia based on the role of institutions.

The multisector watershed arrangement has involved many actors from various sectors of government organizations. The different regulatory patterns of the multiorganizations give birth to many legal products or policies. For the past 15 years or so, DAS laws and regulations have moved dynamically [5]. This results in a lack of synchronization between rules depending on the policy actors who make them. Overall, if we summarize the DAS laws and regulations, the main topics discussed are planning, organizing, evaluation, and briefing (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overlapping roles of actors in watershed management.

Table 2 Explanation: Management Office Watershed (MOW), Directorate General of Water Resources (DGWR), Watershed Forum (WF), Jasa Tirta (JT), Ministry of Forest (MF), Ministry of Maritime (MM), Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MEF), Conservation of Water Resource and Watershed (CWRW), Unit of Water Resources Service (UWRS), Government of East Java Province (GEJP), Ministry of Public Works and Housing Profile (MPWHP), Unit of Technical Implementation Brantas (UTIB).

In the planning of watersheds, the government agencies are authorized in terms of watershed governance planning, namely the Ministry of Public Works and Housing Profile with a score of 5.1, then the Directorate General of Water Resources, which has a score of 4.9, followed by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry with a score of 2.5, and the Ministry of Forest with the smallest score 1.9. Next, in the language of organizing around DAS, the Ministry of Forest has a score of 0.91; this is following Law number 23 of 2014 concerning the Regional Government, of which Article 14 states that watershed management is a forestry affair with the following details: (1) Central Government for the management of watershed management; and (2) Provincial Government for matters of implementing cross-regency/municipal watershed management.

Discussions related to the evaluation of the highest authority are in the Directorate General of Water Resources and the Ministry of Public Works and Housing Profile with scores of 3.9 and 4.4, respectively (Table 2), and the Ministry of Forest with a score of 0.3. Of the three government institutions, all levels are central, and this shows that the scope of evaluation discussion lies with the central government. Furthermore, in the debate on the briefing or operational implementation of watershed management, three institutions are implicated in regulating watershed regulations, namely the Directorate General of Water Resources, The Government of East Java Province, and the Ministry of Public Works Housing Profile. Among the highest scores is the Government of East Java Province since, incidentally, the study object is the Brantas river basin.

Implementing watershed management, starting from planning, organizing, evaluating, and directing or implementing, must follow the hierarchy and role. Each level of the scale has a different position. Government Regulation number 15 of 2010 concerning spatial planning implementation is a derivative of Law number 26 of 2007 concerning spatial planning, map scale, or work scale between regency/city, Provincial, and Central Governments. This is supported by PP number 37 of 2012 that watershed management is implemented following the spatial planning and management of water resources based on the provisions of the prevailing laws and regulations.

5. Discussion

This study’s critical finding is that the regulation of watershed management in Indonesia is related to planning, implementation, management, institutional, coordination, evaluation, and monitoring activities, which confirms that the Indonesian government has made efforts to manage watersheds according to organizational management standards in general [38]: that is, at least in prioritizing planning, implementation, and evaluation activities. In Indonesia, watershed management regulations are directed at realizing integrated watershed management, supported by the linkage of watershed management activities, namely planning, implementation, management, institutionalization, coordination, evaluation, and monitoring activities [39]. This finding confirms that Indonesia’s watershed management regulations show regulations that pay attention to watershed management that involve suitable management activities, which illustrates reasonable regulations for watershed governance, namely regulations that regulate integrated, participatory, and collaborative water resources management [40]. This aims to achieve sustainable watershed management.

The Indonesian government emphasizes that watershed management regulations are directed at realizing good watershed management, which is determined by good river flow management, namely river flow management that integrates river sustainability and the socioeconomic environment [41]. This study’s findings reveal that watershed management activities are the key to the success of realizing good water resources management, which is determined by supervision activities, strong institutions, clarity of institutional power and authority, and the maturity of planning, monitoring, evaluation, and supervision. Thematic analysis of watershed management regulations in this study reveals that the Indonesian government focuses on organizing. More specifically, watershed management activities are related to government activities, designing institutions that support watershed sustainability, government supervision of watershed management, and the integration of watershed management between sustainable environmental issues, social, and economic issues. Evaluation activities have also become the center of attention of the Indonesian government in managing watersheds [42]. Watershed management evaluation activities consist of monitoring and reporting activities.

Organizing activities and evaluation activities in watershed management are the most significant concern to the Indonesian government compared to planning activities that consist of coordination and participation [43,44]. The lack of government attention to planning activities in watershed management shows that the government does not consider planning activities important in realizing good watershed management, namely integrated, collaborative, and sustainable watershed management. This finding confirms that the Indonesian government does not have a good watershed management plan, which impacts the unclear direction of watershed management in Indonesia [45]. In integrated watershed management, planning activities are the first steps that the government must pay attention to and take seriously in realizing sustainable watershed management [46]. Furthermore, planning activities are activities that determine the availability of a watershed management roadmap used as a reference for formulating watershed management policies. Therefore, the lack of government attention to watershed management planning activities reveals that the government does not understand integrated and sustainable watershed management [38].

This study also reveals that the Indonesian government does not pay attention to socialization, coordination, cooperation, and information activities that support good watershed management in Indonesia [25]. The lack of government attention to these activities results in unclear watershed management mechanisms in Indonesia, overlapping roles of central and regional governments, and unclear watershed management policies, which results in sectoral conflicts between the central government and local governments [39]. This finding confirms that the Indonesian government does not yet have an institutional design supporting good watershed management. The central government and local governments have different perceptions and policies towards watershed management; even among them, there is a struggle and the transfer of responsibility for watershed management [47]. Apart from conflicts between the central and regional governments, clashes also occurred between government agencies and private institutions assigned by the state to manage watersheds, such as Jasa Tirta and Perhutani. Although Jasa Tirta and Perhutani are state-formed institutions, these two institutions have different orientations and views on watershed management, which causes conflict between the two institutions.

The unclear watershed management mechanism in Indonesia is a direct consequence of the centralization of watershed management. The centralization of watershed management is reflected in the central government’s watershed management regulations through laws, government regulations, presidential regulations, and ministerial regulations. The central government control environment in watershed management is planning, regulating, and evaluating activities [24]. The three scopes of watershed management are the essential parts in realizing integrated and sustainable watershed management. The central government can maximize its role by using its authority to synergize and invite other stakeholders to be involved in watershed management. Unfortunately, Indonesia’s watershed management regulations do not authorize local governments to take part in planning, regulating, and evaluating watershed management activities. Local governments only play a role in socialization, communication, coordination, and implementation of watershed management regulations made by the central government [48]. The watershed management regulatory model does not represent an integrated watershed management model, which confirms that the institutional design of watershed management fit in Indonesia has not been appropriately formulated.

The centralization of watershed management in Indonesia impacts the overlapping roles of the government in watershed management [40]. In watershed planning activities, four central government agencies have the authority to formulate watershed management policies. The four institutions are as follows: the Ministry of Public Works and Housing Profile, the Directorate General of Water Resources, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, and the Ministry of Forest. In the evaluation of watershed management, three government agencies play a role, namely the Directorate General of Water Resources, the Ministry of Public Works and Housing Profile, and the Ministry of Forest. Three government agencies are involved in the implementation of watershed management policies, namely the Directorate General of Water Resources, the local government, and the Ministry of Public Works and Housing Profile. The government’s overlapping role in watershed management in Indonesia confirms that the institutional fit for watershed management in Indonesia has not been well designed, which has resulted of the overlapping of government institutions in managing watersheds in Indonesia.

6. Conclusions and Research Limitations

This study’s findings reveal that watershed management in Indonesia shows good watershed management because watershed management is related to planning, implementing, organizing, evaluating, and directing activities. However, among these watershed management activities, the Indonesian government has prioritized activities for regulating and evaluating watershed management over planning, implementation, and direct activities. The Indonesian government has neglected planning, performance, and immediate actions, resulting in unclear watershed management in Indonesia. The fuzzy watershed management in Indonesia is a direct consequence of the centralization of watershed management. The central government plays a dominant role compared to local governments in watershed management. The domination of the central government’s role illustrates that watershed management in Indonesia is not yet integrated between the central and regional governments. Another problem in the centralization of watershed management is the overlapping roles of central government agencies in watershed management. Many government agencies have authority in planning, evaluating, and directing activities, which results in sectoral conflicts between central government agencies in the direction of watersheds in Indonesia.

This study confirms that the Indonesian government has not succeeded in realizing integrated, participatory, and collaborative watershed management, which also ensures that watershed management in Indonesia has not been supported by institutional designs that support well-functioning watershed management. Therefore, the Indonesian government needs to present institutional arrangements, such as legal regulations that regulate watershed management, have a clear division of watershed management authority, and prioritize an integrated, participatory, and collaborative watershed management mechanism.

This study has limitations on the aspect of data use. This study’s primary data are the laws and regulations relating to watershed management in Indonesia, which can only reveal normative problems in watershed management in Indonesia. Meanwhile, practical problems have not been disclosed in this study. Therefore, subsequent research needs to use field data such as survey data, interviews, focus group discussions, and observations analyzed using qualitative and quantitative approaches. The use of data and research approaches contributes to watershed management research in Indonesia, particularly in research methodology, watershed management policies, and scientific documents that support watershed management in Indonesia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.S.; methodology, A.N., S.S. and A.R.; software, I.T.S. and M.J.L.; validation, M.K. and A.A.R.; formal analysis, T.S. and S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K.; writing—review and editing, M.K.; project administration, A.R. and A.A.R.; funding acquisition, T.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank for the Universitas Muhammadiyah Malang and Jusuf Kalla Scholl of Government, Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta concerning this collaboration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Epstein, G.; Pittman, J.; Alexander, S.M.; Berdej, S.; Dyck, T.; Kreitmair, U.; Rathwell, K.; Villamayor-Tomas, S.; Vogt, J.; Armitage, D. Institutional fit and the sustainability of social-ecological systems. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chikozho, C. Policy and institutional dimensions of small-holder farmer innovations in the Thukela River Basin of South Africa and the Pangani River Basin of Tanzania: A comparative perspective. Phys. Chem. Earth 2005, 30, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergsten, A.; Jiren, T.S.; Leventon, J.; Dorresteijn, I.; Schultner, J.; Fischer, J. Identifying governance gaps among interlinked sustainability challenges. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 91, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donie, S. Institutional Analysis of Watershed Manangement in Batam Island. Forum Geografi 2016, 30, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pambudi, A.S. Watershed Management in Indonesia: A Regulation, Institution, and Policy Review. J. Perenc. Pembang. Indon J. Dev. Plan. 2019, 3, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Kope, L.; Miller-Stevens, K. Rethinking a Typology of Watershed Partnerships. Public Works Manag. Policy 2014, 20, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagaya, S.; Wada, T. The application of environmental governance for sustainable watershed-based management. Asia-Pac. J. Reg. Sci. 2021, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.; Güneralp, B.; Kreuter, U.P.; Güneralp, İ.; Filippi, A.M. Spatial and temporal changes in biodiversity and ecosystem services in the San Antonio River Basin, Texas, from 1984 to 2010. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 619–620, 1259–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadani, I.G.A.W. Model Pemanfaatan Modal Sosial Dalam Pemberdayaan Masyarakat Pedesaan Mengelola Daerah Aliran Sungai (Das) Di Bali. Wicaksana J. Lingkung. Dan Pembang. 2017, 1, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmawati, F.; Erani, A.; Ashar, K.; Santoso, D.B. The Institutional Coordination of Brantas Watershed Management. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 5, 207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Young, O.R. The architecture of global environmental governance: Bringing science to bear on policy. Glob. Environ. Politics 2008, 8, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCaro, D.A.; Stokes, M.K. Public participation and institutional fit: A social-psychological perspective. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagedorn, K. Particular requirements for institutional analysis in nature-related sectors. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2008, 35, 357–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, O.R. Institutional dynamics: Resilience, vulnerability and adaptation in environmental and resource regimes. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2010, 20, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M. Diagnosing institutional fit: A formal perspective. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, H.; Lejano, R.P. Interpreting institutional fit: Urbanization, development, and China’s “land-lost”. World Dev. 2014, 61, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uda, S.K.; Schouten, G.; Hein, L. The institutional fit of peatland governance in Indonesia. Land Use Policy 2018, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandaragoda, D.J. A Framework for Institutional Analysis for Water Resources Management in a River Basin Context. Int. Water Manag. Inst. (IWMI) 2000, 2, 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Savenije, H.H.G.; Van Der Zaag, P. Conceptual framework for the management of shared river basins; With special reference to the SADC and, EU. Water Policy 2000, 2, 9–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, V.S.; Geoffrey, T.; Peter, P. Critical Review of Integrated Water Resources Management: Moving beyond Polarised Discourse. 2008. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/ (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Bandaragoda, D.J.; Babel, M.S. Institutional development for IWRM: An international perspective. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 2010, 8, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulazzaky, M.A. Challenges of integrated water resources management in Indonesia. Water 2014, 6, 2000–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Li, Y.; Huang, G.; Zhuang, X.; Nie, S. Sustainable Water-Resources Allocation Through a Trading-Oriented Mechanism Under Uncertainty in an Arid Region. Clean Soil Air Water 2018, 46, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margerum, R.D. A typology of collaboration efforts in environmental management. Environ. Manag. 2008, 41, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheson, J.M. Institutional failure in resource management. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2006, 35, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, H.M.T.; Hickey, G.M.; Sarker, S.K. A framework for evaluating collective action and informal institutional dynamics under a resource management policy of decentralization. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 83, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekstrom, J.A.; Young, O.R. Evaluating functional fit between a set of institutions and an ecosystem. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meynen, Q.W.; Doornbos, M. Decentralizing Natural Resource Management: A Recipe for Sustainability And Equity. Europ. J. Develop. Res. 2004, 16, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanguilig, H.C.; Tanguilig, V.C. Institutional aspects of local participation in natural resource management. Field Actions Sci. Rep. J. Field Actions 2009, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Randhir, T.O.; Raposa, S. Urbanization and watershed sustainability: Collaborative simulation modeling of future development states. J. Hydrol. 2014, 519, 1526–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, R. Sustainable Watershed Management: Institutional Approach. Econ. Political Wkly. 2000, 35, 3435–3444. [Google Scholar]

- Lebel, L.; Nikitina, E.; Pahl-Wostl, C.; Knieper, C. Institutional fit and river basin governance: A new approach using multiple composite measures. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.; Ramu, K.; Kemper, K. Institutional and Policy Analysis of River Basin Management: The Brantas River Basin, East Java, Indonesia; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Camarinha-Matos, L.; Fornasiero, R.; Afsarmanesh, H. Collaborative Networks as a Core Enabler of Industry 4.0. In Proceedings of the 18th Working Conference on Virtual Enterprises (PROVE), Vicenza, Italy, 18–20 September 2017; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Basco-Carrera, L.; Warren, A.; van Beek, E.; Jonoski, A.; Giardino, A. Collaborative modelling or participatory modelling? A framework for water resources management. Environ. Model. Softw. 2017, 1, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, K.; Dinar, A.; Blomquist, W. Institutional and Policy Analysis of River Basin Management Decentralization. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2005, 6, 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, S. Coordinating invasive plant management among conservation and rural stakeholders. Land Use Policy 2018, 81, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathwell, K.J.; Peterson, G.D. Connecting social networks with ecosystem services for watershed governance: A social-ecological network perspective highlights the critical role of bridging organizations. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simms, R.; Harris, L.; Joe, N.; Bakker, K. Navigating the tensions in collaborative watershed governance: Water governance and Indigenous communities in British Columbia, Canada. Geoforum 2016, 73, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanlon, J.; Olivier, T.; Schlager, E. Institutional adaptation and effectiveness over 18 years of the New York city watershed governance arrangement. Environ. Pract. 2017, 19, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tol Smit, E.; de Loë, R.; Plummer, R. How knowledge is used in collaborative environmental governance: Water classification in New Brunswick, Canada. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2015, 58, 423–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, S.K.; Sahay, S. Participation through communicative action: A case study of gis for addressing land/water development in india’. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2003, 10, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Roberts, R.M.; Jones, K.W.; Cottrell, S.; Duke, E. Examining motivations influencing watershed partnership participation in the Intermountain Western United States. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 107, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foran, T.; Penton, D.J.; Ketelsen, T.; Barbour, E.J.; Grigg, N.; Shrestha, M.; Lebel, L.; Ojha, H.; Almeida, A.; Lazarow, N. Planning in Democratizing River Basins: The Case for a Co-Productive Model of Decision Making. Water 2019, 11, 2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.M.; Lynch, A.J.; Young, N.; Cowx, I.G.; Beard, T.D.; Taylor, W.W.; Cooke, S.J. To manage inland fisheries is to manage at the social-ecological watershed scale’. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 181, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, Z.F.; Nasaruddin, A.; Abd Kadir, S.N.; Musa, M.N.; Ong, B.; Sakai, N. Community-based shared values as a ‘Heart-ware’ driver for integrated watershed management: Japan-Malaysia policy learning perspective. J. Hydrol. 2015, 530, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medema, W.; Adamowski, J.; Orr, C.J.; Wals, A.; Milot, N. Towards sustainable water governance: Examining water governance issues in Québec through the lens of multi-loop social learning. Can. Water Resour. J. 2015, 40, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).