The Effects of Local Food and Local Products with Geographical Indication on the Development of Tourism Gastronomy

Abstract

1. Introduction

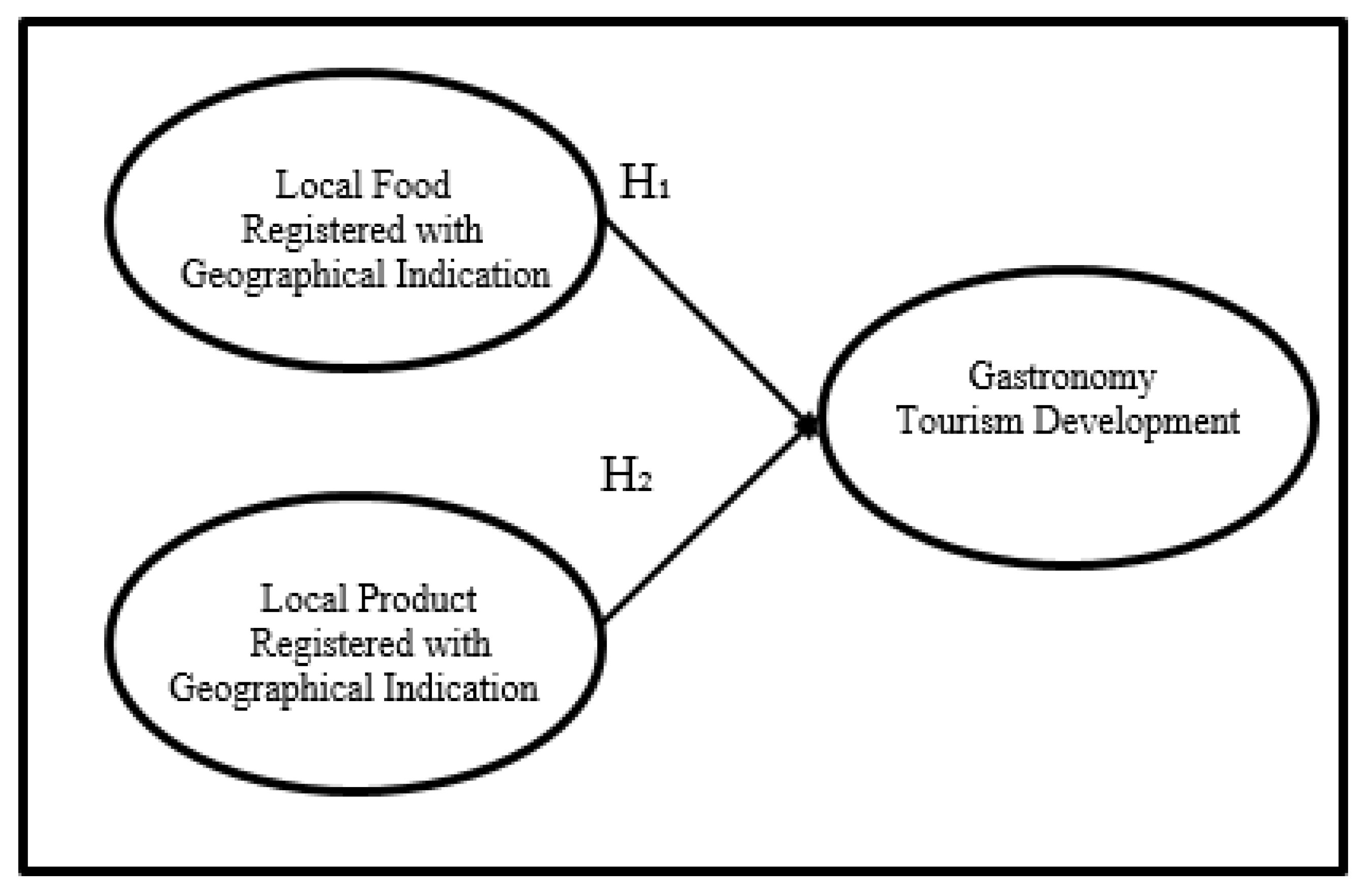

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis

2.1. Gastronomy Tourism

2.2. Geographical Indications

2.3. The Effect of Products with Geographical Indication on the Development of Gastronomy Tourism

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Survey Instrument

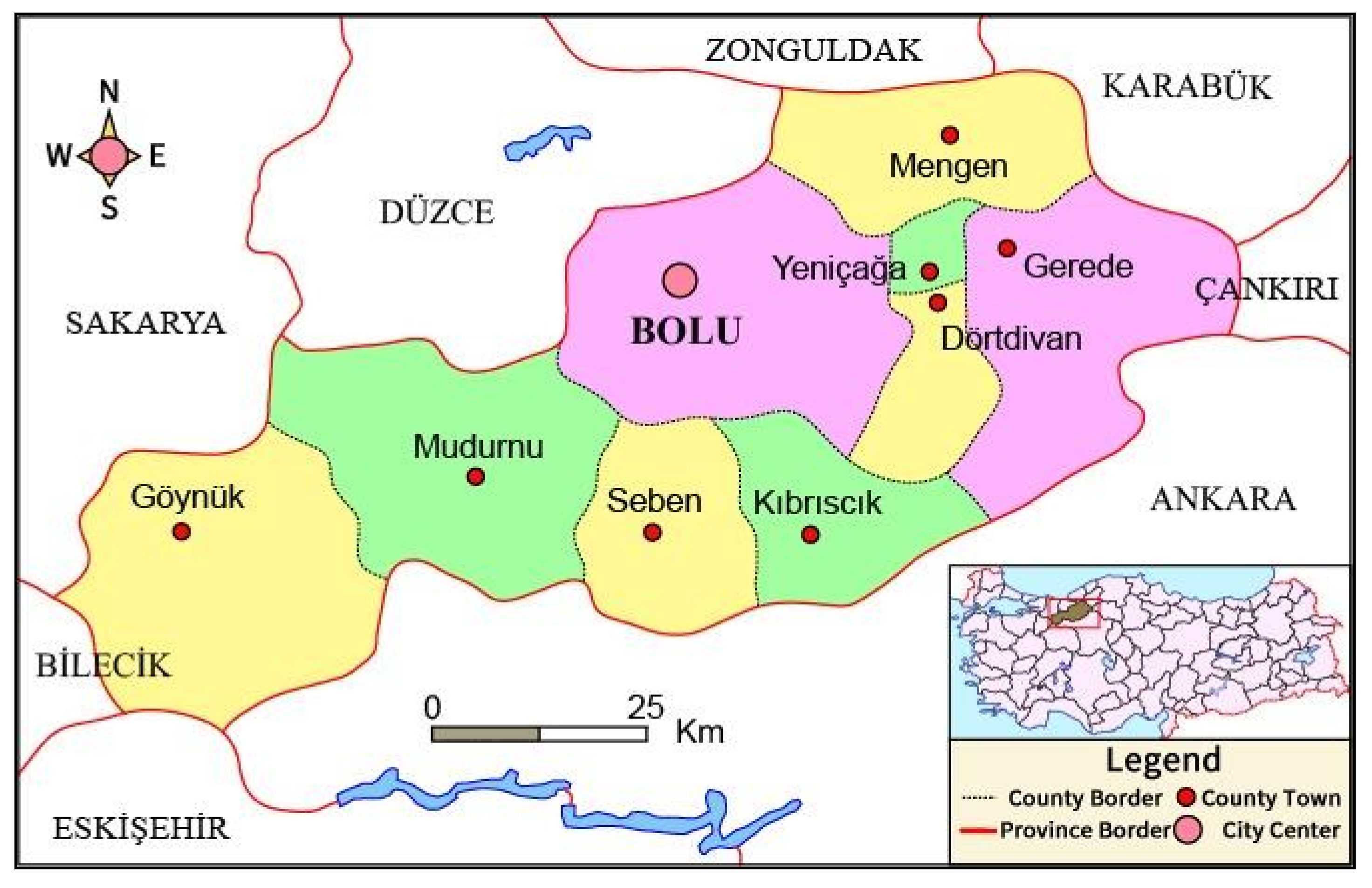

3.2. Data Collection and Sampling

3.3. Data Analysis

3.4. Validity and Reliability

4. Result

4.1. Demographic Information of Participants

4.2. Results of the Measurement Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Practical Implementation

5.2. Theoretical Implementation

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roininen, K.; Arvola, A.; Lahteenmaki, L. Exploring consumer perceptions of local food with two different qualitative techniques: Laddering and word association. Food Qual. Prefer. 2006, 17, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armesto, X.A.; Gómez, B. Productos agroalimentarios de calidad, turismo y desarrollo local: El caso del Priorat. Cuad. Geogr. 2004, 34, 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kivela, J.; Crotts, J.C. Tourism and gastronomy: Gastronomy’s influence on how tourists experience a destination. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2006, 30, 354–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Costello, C. Segmenting visitors to a culinary event: Motivations, travel behavior, and expenditures. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2009, 18, 44–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikkanen, I. Maslow’s hierarchy and food tourism in Finland: Five cases. Br. Food J. 2007, 109, 635–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgado, E.M. Turning food into a gastronomic experience: Olive oil tourism. Options Mediter. 2013, 106, 97–109. Available online: http://om.ciheam.org/article.php?IDPDF=6809 (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- Rodrigo, I.; da Veiga, J.F. From the local to the global: Knowledge dynamics and economic restructuring of local food. In Naming Food After Places: Food Relocalisation and Knowledge Dynamics in Rural Development; Papadopoulos, A.G., Fonte, M., Eds.; Taylor & Francis eBooks: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2016; p. 127. [Google Scholar]

- Josling, T. What’s in a Name? The Economics, Law and Politics of Geographical Indications for Foods and Beverages; Paper presented to the Institute for International Integration Studies; Trinity College: Dublin, Ireland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Björk, P.; Kauppinen-Räisänen, H. Local food: A source for destination attraction. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Rand, G.E.; Heath, E. Towards a framework for food tourism as an element of destination marketing. Curr. Issues Tour. 2006, 9, 206–234. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, K.; Jang, S.C. Intention to experience local cuisine in a travel destination: The modified theory of reasoned action. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2006, 30, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ab Karim, M.S.; Lia, C.B.; Aman, R.; Othman, M.; Salleh, H. Food image, satisfaction and behavioral intentions: The case of Malaysia’s Portuguese cuisine. In Proceedings of the International CHRIE Conference-Refereed Track, Denver, CO, USA, 29 July 2011; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Qing-Chi, C.G.Q.; Chua, B.L.; Othman, M.; Ab Karim, S. Investigating the structural relationships between food image, food satisfaction, culinary quality, and behavioral intentions: The case of Malaysia. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2013, 14, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peštek, A.; Činjarević, M. Tourist perceived image of local cuisine: The case of Bosnian food culture. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1821–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaconescu, D.M.; Moraru, R.; Stănciulescu, G. Considerations on gastronomic tourism as a component of sustainable local development. Amfiteatru Econ. J. 2016, 18, 999–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi, C. Food and gastronomy for sustainable place development: A multidisciplinary analysis of different theoretical approaches. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privitera, D.; Nedelcu, A.; Nicula, V. Gastronomic and food tourism as an economic local resource: Case studies from Romania and Italy. GeoJ. Tour. Geosites 2018, 21, 143–157. [Google Scholar]

- Teuber, R. Geographical indications of origin as a tool of product differentiation: The case of coffee. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2010, 22, 277–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostino, M.; Trivieri, F. Geographical indication and wine exports. An empirical investigation considering the major European producers. Food Policy 2014, 46, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderighi, M.; Bianchi, C.; Lorenzini, E. The impact of local food specialties on the decision to (re) visit a tourist destination: Market-expanding or business-stealing? Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seal, P.P.; Piramanayagam, S. Branding geographical indication (GI) of food and its implications on gastronomic tourism: An Indian perspective. In Proceedings of the 8th Advances in Hospitality and Tourism Marketing and Management (AHTMM) Conference, Bangkok, Thailand, 25–29 June 2018; p. 132. [Google Scholar]

- Zahari, M.S.M.; Jalis, M.H.; Zulfifly, M.I.; Radzi, S.M.; Othman, Z. Gastronomy: An opportunity for Malaysian culinary educators. Int. Educ. Stud. 2009, 2, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveci, B.; Türkmen, S.; Avcıkurt, C. Relationship between rural tourism and gastronomy tourism: The case of Bigadiç. Int. J. Soc. Econ. Sci. 2013, 3, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Çavuşoğlu, M.A. Research on gastronomy tourism and Cypriot culinary culture, I. In Proceedings of the International IV National Eğirdir Tourism Symposium, Isparta, Turkey, 1–3 December 2011; pp. 527–538. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Sharples, L.; Mitchell, R.; Macionis, N.; Cambourne, B. Food Tourism Around the World: Development, Management and Markets; Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nesterchuk, I. Gastronomic tourism: History, development and formation. Zeszyty Naukowe Wyższej SzkołyTuryst. Ekol. 2020, 9, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, R.J.; Ottenbacher, M.C. Culinary tourism—A case study of the gastronomic capital. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2010, 8, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, J.; Kamakura, W.A. Country of origin: A competitive advantage. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1999, 16, 225–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangjee, D.S. Proving provenance? Geographical indications certification and its ambiguities. World Dev. 2017, 98, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaelani, A.K.; IGAKR, H.; Karjoko, L. Development of tourism based on geographic indication towards to welfare state. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 29, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar]

- Suratno, B. Protection of geographical indications. IP Manag. Rev. 2004, 2, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Escudero, S. International Protection of Geographical Indications and Developing Countries; Trade-Related Agenda Development and Equity (Trade) (No. 10). Working Paper; South Centre: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sünnetçioğlu, S.; Can, A.; Durlu-Özkaya, F. The importance of geographical marking in slow tourism. In Proceedings of the 13th National Tourism Congress, Antalya, Turkey, 6–9 December 2012; pp. 953–962. [Google Scholar]

- Kastenholz, E.; Davis, D.; Paul, G. Segmenting tourism in rural areas: The case of north and central Portugal. J. Travel Res. 1999, 37, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyimothy, S.; Rassing, C.R.; Wanhill, S. Marketing works: A study of the restaurants on Bornholm, Denmark. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2000, 12, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joppe, M.; Martin, D.W.; Waalen, J. Toronto’s Image as a Destination: A comparative importance-satisfaction analysis by origin of visitor. J. Travel Res. 2001, 39, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorcaru, I.A. Gastronomy tourism—A sustainable alternative for local economic development. Ann. Univ. Dunarea Jos Galati Fascicle I Econ. Appl. Inform. 2019, 25, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlu-Özkaya, F.; Sünnetçioğlu, S.; Can, A. The role of geographical indication in sustainable gastronomy tourism mobility. J. Tour. Gastron. Stud. 2013, 1, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Akdağ, G.; Özata, E.; Sormaz, Ü.; Çetinsöz, B.C. A new alternative for sustainable gastronomy tourism: Surf & turf. J. Tour. Gastron. Stud. 2016, 4, 270–281. [Google Scholar]

- López-Guzmán, T.; Sánchez-Cañizares, S. Gastronomy, tourism and destination differentiation: A case study in Spain. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2012, 1, 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hazarhun, E.; Tepeci, M. The contribution of the local products and meals which have geographical indication to the development of gastronomy tourism in Manisa. J. Contemp. Tour. Res. 2018, 2, 371–389. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/guntad/issue/38617/447968 (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- Ören, V.E.; Ören, T.Ş. Gastronomi turizmi kapsamında sürdürülebilirlik: Ebem köftesi örneği. Turk. Stud. Soc. Sci. 2019, 14, 151–162. [Google Scholar]

- Correia, A.; Moital, M.; Da Costa, C.F.; Peres, R. The determinants of gastronomic tourists’ satisfaction: A second-order factor analysis. J. Food Serv. 2008, 19, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durusoy, Y.Y. An Analytical Study on the Perception of Geographically Indicated Gastronomic Products by the People of the region: The Case of Kars Cheddar. Ph.D Thesis, Haliç University Institute of Social Sciences, Istanbul, Turkey, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Turkish Patent Institute. Available online: https://www.turkpatent.gov.tr/TURKPATENT/ (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- Bolu Provincial Directorate of Culture and Tourism. Available online: https://bolu.ktb.gov.tr/ (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- Bolu Province Air Quality Analysis Report. Available online: https://kiathm.csb.gov.tr/static/uploads/2018/11/bolu.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- Aaker, D.A.; Kumar, V.; Day, G.S. Marketing Research, 9th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kerlinger, F.N. Foundations of Behavioral Research; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed.; Prentice-Hall Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, J. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sekaran, U. Business Research Methods: A Skill-Building Approach, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton, C.D. Basic Concepts and Procedures of Confirmatory Factor Analysis; Reports-Evaluative (142), Speeches/Meeting Papers (150); Educational Research Association: Austin, TX, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S. Applied Multivariate Techniques; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, J. Applied Regression Analysis, Linear Models, and Related Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Saldkind, N.J. Encyclopedia of Measurements and Statistics; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Turkish Travel Agencies (TÜRSAB). TÜRSAB Gastronomy Tourism Report. 2015. Available online: http://www.tursab.org.tr/dosya/12302/tursab-gastronomi-turizmi-raporu_12302_3531549.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Feo, F. Turismo gastronómico en Asturias. Cuadernos Tur. 2005, 34, 77–96. [Google Scholar]

- Velissariou, E.; Mpara, E. Local products and tourism gastronomy in rural areas Evidence from Greece. In Proceedings of the MIBES International Conference, Thessaloniki, Greece, 30 May–1 June 2014; pp. 253–265. [Google Scholar]

- Haven-Tang, C.; Jones, E. Using local food and drink to differentiate tourism destinations through a sense of place: A story from Wales-dining at Monmouthshire’s great table. J.Culin. Sci. Technol. 2008, 4, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessière, J. Local development and heritage: Traditional food and cuisine as tourist attractions in rural areas. Sociol. Rural 1998, 38, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestek, A.; Nikolic, A. Role of traditional food in tourist destination image building: Example of the city of Mostar. UTMS J. Econ. 2011, 2, 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Björk, P.; Kauppinen-Räisänen, H. Culinary-gastronomic tourism—A search for local food experiences. Nutr. Food Sci. 2014, 44, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J. Food tourism reviewed. Br. Food J. 2009, 11, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.D. Olives, hospitality and tourism: A Western Australian perspective. Br. Food J. 2010, 112, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, S.; Wang, N. Towards a structural model of the tourist experience: An illustration from food experiences in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.N.S.; Getz, D. Profiling potential food tourists: An Australian study. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 690–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunori, G.; Rossi, A. Synergy and coherence through collective action: Some insights from wine routes in Tuscany. Sociol. Rural. 2000, 40, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charters, S.; Ali-Knight, J. Wine tourism-A thirst for knowledge? Int. J. Wine Mark. 2000, 12, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alant, K.; Bruwer, J. Wine tourism behavior in the context of a motivational framework for wine regions and cellar doors. J. Wine Res. 2004, 15, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alebaki, M.; Iakovidou, O. Segmenting the Greek wine tourism market using a motivational approach. New Medit 2010, 9, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Girardeau, J.M. The Use of Geographical Indications in a Collective Marketing Strategy: The Example of Cognac. Symposium on the International Protection of Geographical Indication WIPO; WIPO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000; pp. 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Niekerk, J. The Use of Geographical Indications in a Collective Marketing Strategy: The Example of the South African Wine Industry. Symposium on the International Protection of Geographical Indication WIPO; WIPO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000; pp. 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, A. The Protection of Geographical Indications in South Africa. Symposium on the International Protection of Geographical Indication WIPO; WIPO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000; pp. 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Vital, F. Protection of Geographical Indications: The Approach of the European Union Symposium on the International Protection of Geographical Indication WIPO; WIPO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000; pp. 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, B.D.; Fernandes, L.R.R.D.M.V.; De Souza, C.G. An overview of geographical indications in Brazil. J. Intel. Prop. Rights 2012, 17, 133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Rangnekar, D. The Socio-Economics of Geographical Indications: A Review of Empirical Evidence from Europe; Issue Paper no 8; International Center for Trade and Sustainable Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, C.T. Memorable tourist experiences and place attachment when consuming local food. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 536–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | Items | Factor Loadings | Explained Variance Rate | Cronbach’s Alfa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local Food Registered with Geographic Indication | Tourism companies can make a difference by organizing gourmet tours to the region. | 0.879 | 29.425 | 0.963 |

| Gastronomy tourism should be used more in the marketing of the region. | 0.878 | |||

| Bolu local cuisine is a cultural value and needs to be preserved. | 0.870 | |||

| A traditional food festival related to the Bolu local cuisine can be organized. | 0.856 | |||

| Bolu local cuisine should be identified with Turkish Culinary Culture. | 0.834 | |||

| Local cuisine has a positive effect on being visited of Bolu. | 0.726 | |||

| The geography of Bolu and the way of production affect the quality of the products. | 0.686 | |||

| The local cuisine has been influenced by other cuisines in the country. | 0.664 | |||

| Gastronomy Tourism Development | Bolu local cuisine has increased the number of local and foreign tourists coming to Bolu. | 0.835 | 26.571 | 0.956 |

| Bolu local cuisine has positively affected gastronomy tourism in Bolu. | 0.807 | |||

| Bolu’s local cuisine is one of the most important reasons why Bolu is visited as a touristic area. | 0.807 | |||

| Bolu local cuisine has provided diversification in accommodation and transportation services in Bolu. | 0.751 | |||

| The competitiveness of gastronomy tourism, which is formed by the local cuisine of Bolu, is high. | 0.746 | |||

| Bolu local cuisine meets the expectations for gastronomic tourism in general. | 0.741 | |||

| Bolu local cuisine has enabled tourism investments to be made in the city of Bolu. | 0.731 | |||

| Bolu local cuisine has contributed to the promotion of the city of Bolu. | 0.713 | |||

| Local Food Registered with Geographic Indication | The production of local products is sufficient for Turkey. | 0.756 | 17.872 | 0.879 |

| Plenty of local products is to get the attention that it deserves in Turkey. | 0.718 | |||

| Bolu local products are easy to access. | 0.694 | |||

| The sale price of Bolu local products is affordable. | 0.667 | |||

| Plenty of local products are well-known in Turkey. | 0.645 | |||

| I think that plenty of local produce are sufficiently known in Turkey. | 0.537 | |||

| Local products are still produced by traditional production methods. | 0.517 | |||

| 73.868 | 0.968 | |||

| n | % | Cumulative Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 234 | 59.8 | 59.8 |

| Male | 157 | 40.2 | 100 | |

| Total | 391 | 100 | ||

| 18–25 | 110 | 28.1 | 28.1 | |

| 26–33 | 126 | 32.2 | 60.4 | |

| Age | 34–41 | 105 | 26.9 | 87.2 |

| 42–49 | 27 | 6.9 | 94.1 | |

| 50 and above | 23 | 5.9 | 100 | |

| Total | 391 | 100 | ||

| Educational Status | Secondary School | 9 | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| High School | 41 | 10.5 | 12.8 | |

| Vocational High School | 42 | 10.7 | 23.5 | |

| Undergraduate Education | 160 | 40.9 | 64.5 | |

| Postgraduate Education | 139 | 35.5 | 100 | |

| Total | 391 | 100 |

| Model | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Regression | 284.765 | 2 | 142.383 | 314.641 | 0.000 |

| Increasing | 175.579 | 388 | 0.453 | |||

| Total | 460.345 | 390 |

| Model | R | R² | Adjusted R² | Standard Error | Durbin-Watson |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.787 | 0.619 | 0.617 | 0.67270 | 2.041 |

| Standardized Coefficient | Collinearity Statistics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Independent Variables | Beta | t | p | Tolerance | VIF |

| 1 | Constant | 1.423 | 0.155 | |||

| Local Food Registered with Geographic Indication | 0.400 | 9.174 | 0.000 | 0.517 | 1.935 | |

| Local Product Registered with Geographic Indication | 0.454 | 10.409 | 0.000 | 0.517 | 1.935 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pamukçu, H.; Saraç, Ö.; Aytuğar, S.; Sandıkçı, M. The Effects of Local Food and Local Products with Geographical Indication on the Development of Tourism Gastronomy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6692. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126692

Pamukçu H, Saraç Ö, Aytuğar S, Sandıkçı M. The Effects of Local Food and Local Products with Geographical Indication on the Development of Tourism Gastronomy. Sustainability. 2021; 13(12):6692. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126692

Chicago/Turabian StylePamukçu, Hüseyin, Ömer Saraç, Sercan Aytuğar, and Mustafa Sandıkçı. 2021. "The Effects of Local Food and Local Products with Geographical Indication on the Development of Tourism Gastronomy" Sustainability 13, no. 12: 6692. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126692

APA StylePamukçu, H., Saraç, Ö., Aytuğar, S., & Sandıkçı, M. (2021). The Effects of Local Food and Local Products with Geographical Indication on the Development of Tourism Gastronomy. Sustainability, 13(12), 6692. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126692