1. Introduction

The HoReCa channel is the set of commercial catering food establishments whose main activity is the production and sale of direct out-of-home consumption of food. Saving possible types of specific establishments, it fundamentally encompasses the subsectors that make up the acronym: hotels, restaurants, and catering. Even if HoReCa is a fundamental part of tourism, there are few academic works in this field as it is a difficult sector to study, largely because the stated objective of many of the official databases is to provide rigorous information on the tourism sector, where accommodation services are clearly prioritized over restoration services, and because the HoReCa establishments are often included under the hospitality umbrella [

1].

The concept of sustainability has grown beyond the idea of environmental stewardship to include social as well as economic aspects [

2]. Creating value for this triple bottom line, i.e., environment, economy, and society, has been the goal of sustainable business models [

3]. The hospitality industry is clearly affected by these three dimensions. The principles of sustainability refer to the environmental, economic, and socio-cultural aspects of tourism development, having to establish an adequate balance between these three dimensions to guarantee its long-term sustainability. Sustainable tourism must ensure viable long-term economic activities that provide well-distributed socio-economic benefits to all stakeholders, including stable employment and income-earning opportunities and social services for host communities, and that contribute to poverty reduction [

4].

While the environmental issues of this industry have been studied from different approaches, such as corporate strategy (new green business), differentiation and cost reduction through environmental management, eco-labels, responsible supply chain, etc. [

5], research on the development of sustainable business models in this industry with an integral approach is still in an incipient stage [

6]. Concerning HoReCa, and from a sustainability perspective, the sector has been a subject of research due to its environmental impact, especially food waste management [

7,

8,

9,

10], its quantification [

11] and the prevention options [

12,

13]. The potential impact that e-commerce and innovative digital technologies can have on hospitality has also been analysed by academic studies [

14,

15,

16,

17]. However, literature review shows few studies focused on the problems associated with the HoReCa distribution channel in general [

18] and that they are mainly focused on the environmental impacts of its supply chain [

19,

20] and on the use of technological advancements in downstream value chains [

21]. Supply chain has been identified as a priority area for the hospitality industry regarding resiliency and sustainability [

22]. The absence of studies on the supply chain in the HoReCa sector from a sustainability perspective that also addresses economic and social aspects, and not only environmental ones, is due in part to two reasons. First, a general one: the fact, as has already been pointed out, that research on sustainable business models in hospitality is still in its initial stage, probably motivated because with the high global growth rates of the sector there was no urgency in rethinking models. Secondly, because the HoReCa sector supply chain has traditionally been linear and has remained fairly stable for decades, although five distribution models had been identified [

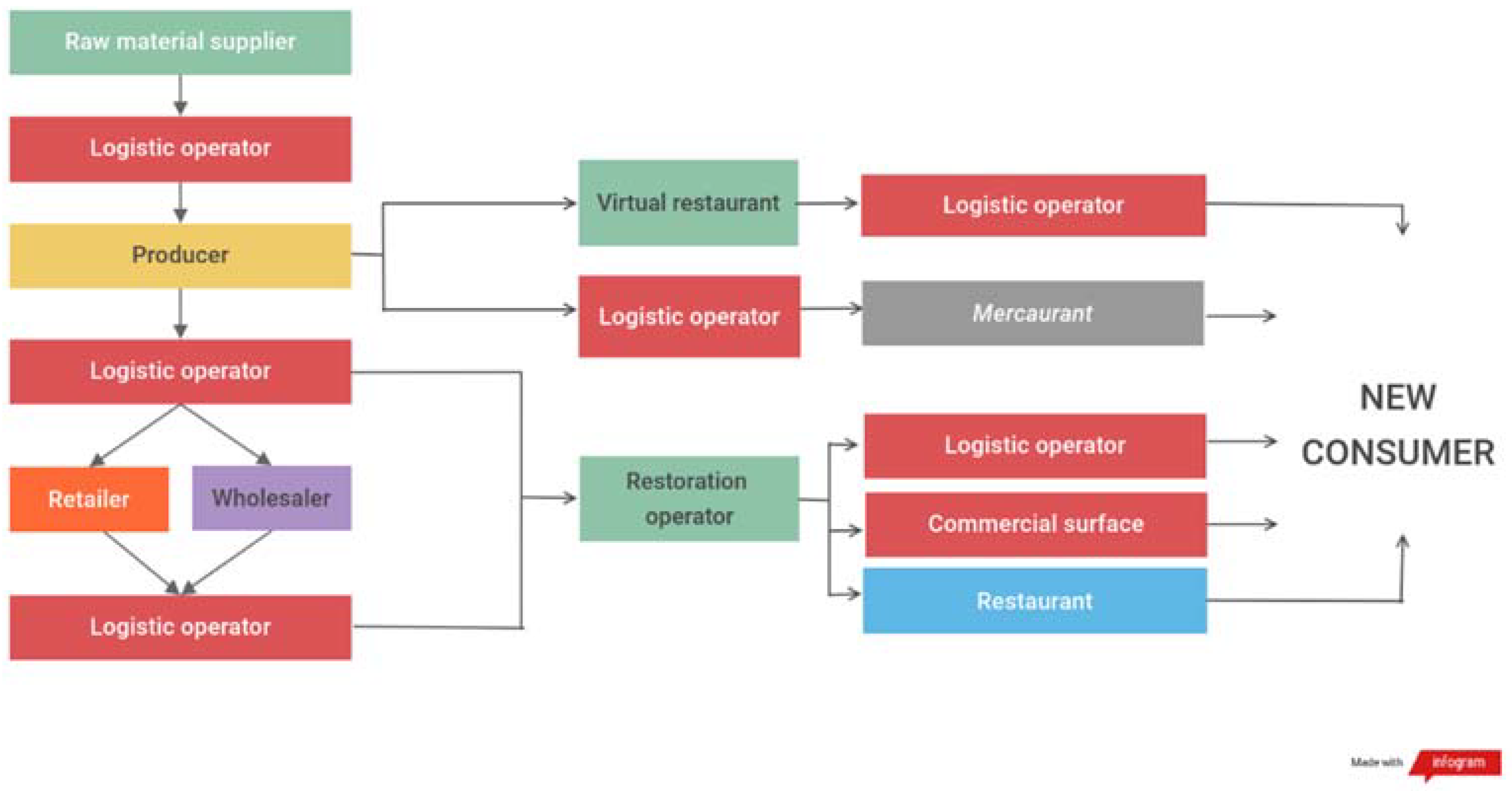

18], condensed in

Figure 1.

Suddenly, the viability of traditional business models has been questioned, due to the global crisis in the hospitality industry, the massive cessation of activity for months of the majority of the HoReCa sector, and the changes in demand and consumption habits. The challenge of exploring sustainable business models and rethinking its whole supply chain becomes urgent. Some reflections associated with the HoReCa sector in the long term will be addressed in this manuscript: first, through what has been the evolution of the sector during the pandemic, and second, exploring how supplier companies in the sector (for example, beverages and food) will rethink their “route to market” model for the hospitality channel and will adjust it to a structurally different post-crisis dynamic.

The pandemic is giving rise to specific literature on its impact [

23,

24] on how companies in the hospitality sector have managed, and are managing, periods of crisis [

25,

26] and on the challenges for a new tourism in the post-COVID-19 risk scenario [

27,

28]. When external unpredictable shocks occur, more and new research is necessary [

29] because accurate forecasting of the full scale of the impact on the tourism industry and market recovery is critical for strategic planning by tourist destinations and tourism-related businesses [

30]. The profound impact of the coronavirus pandemic on global tourism activity has rendered statistical approaches on tourism demand forecasting obsolete because they cannot capture the impacts of global unanticipated events [

31]. An appropriate alternative is to provide analysis based on different scenarios [

29] as an approach to anticipate disruptions in the tourism system [

32].

In this context, the objective of this article is to carry out a prospective analysis on how the changes in the behaviour of consumers during the pandemic and the uncertainties regarding the exit from the health emergency can give rise to social trends with a high impact on the HoReCa sector in the coming years and, specifically, how they will affect the HoReCa supply chain. The paper goes from the literature and data available to developing some very interesting scenarios and possibilities for the sector.

The paper is structured as follows: identification of a relevant research problem from a review of literature focused on the HoReCa channel (

Section 1), description of the methodology (

Section 2), presentation of the impact of COVID-19 on the HoReCa sector in Spain (

Section 3), prospective analysis of the future of the sector at different timeframes (

Section 4), and, finally, conclusions and implications of the findings (

Section 5).

2. Methodology

According to the most recent academic literature in tourism and hospitality, cited above, scholars should turn their attention to alternative methods for predicting the evolution of these sectors. Therefore, our research proposes an interdisciplinary approach with contributions from the fields of future studies and strategic and competitive intelligence. These complementary disciplines seek to identify signs of the future in the present and to discover how those signs anticipate trends, drawing a realistic picture of the future by exposing various possible scenarios.

Analysis of the environment of the actual HoReCa sector and its foreseeable evolution has been carried out using intelligence techniques such as the identification and analysis of trends through early warning indicators and scenario planning. A trend evolves through four stages: emerging trend, when it begins to be detected; growing trend, when it strengthens and achieves traction capacity; mature trend, when it is consolidated and rules the present; and descent trend, when it weakens to its demise. In addition, trends can be macros, that is, they are imposed in the long term, are lasting over time, and affect a sector in a generalized way, or can be micros, that is, they act in the short term, expire before, and have a more local sphere of influence. The micro-trends are maintained and impact as long as they are aligned with the macro-trends, and these in turn arise, grow and consolidate thanks to the success of micro-trends. We have decided in this research to detect mainly emerging and growing trends and explore if the new micro-trends in consumer behaviour are aligned with the macro-trends.

Once the operating trends have been identified, it is the turn of scenario analysis. Scenario construction is usually applied in intelligence and crises management when it is difficult to predict the evolution of a complex situation or events, generally due to the presence of new and unexpected variables. The scenario planning technique typically includes a description of an initial situation, the identification of the key driving forces, and the design of the most probable future changes, accompanied, sometimes, by their probability of success. Scenario-based forecasting has been incorporated in previous tourism research in times of crises [

29,

33].

The building of near- and longer-term time horizons in today’s hazardous world requires thinking with an open mind about the recovery of the economic growth, the potential existence of successive and new waves of pandemic, and, consequently, their impact on food consumption and consumer behavioor in the HoReCa channel. In the absence of investigations due to the proximity of what has happened, government public sources and reports of international relevance about behaviour of food and beverage consumers and market trends, published by consulting companies and public research institutes, have been identified and analysed. The use of quality secondary information sources instead of primary ones does not imply a decrease in the scientific validity of a study when the principle of strategic intelligence of never accepting a single information authority is respected [

34]. The method of competitive intelligence consists of the collection, transmission, analysis, and dissemination of relevant information publicly available and ethically and legally obtained, to produce actionable knowledge for the improvement of the process of decision making [

35]. Otherwise, the findings of the information sources used are based on questionnaires and interviews applied to HoReCa sector users and experts, conducted during the health pandemic in Spain and Europe in 2020 and 2021. The specific sources will be indicated when data and results obtained from these studies are referenced.

Foresight studies always focus on concrete and specific realities, such as social phenomena, economic sectors, human groups, territories, etc. The future is not a theoretical construct without a basis in reality; it is a result of changes that occur in the present from the confluence of trends, internal changes, external facts, and actions of agents that operate in each place and time. The future is not predetermined; it is a horizon open to various and alternative routes with various probabilities of success, which must be understood to design strategies, to make decisions, and to guide current activities, in accordance with the evolution of the present. Therefore, the prospective produces actionable insights that allow risks to be avoided and opportunities to be taken advantage of by public institutions and private corporations.

Due to the need to focus the prospective analysis on concrete reality, and specially on consumer behaviour, the HoReCa sector in Spain has been taken as a field of study to observe and propose the possibilities of configuration of a new supply chain in the hospitality sector. Spain has been chosen for three characteristics of the HoReCa sector in this country: its cultural and economic importance in Spanish society, the dependence of the sector on the recovery of national and international tourism after its paralysis due to the pandemic, and because consumers have gained prominence in their contribution to shaping the structure of the sector [

36]. In addition, Spain has made a clear commitment to a tourism policy based on sustainability, aligning with one of the main world trends in tourism and their strategies and expected results becoming a focus of attention in the coming years, due to the preeminent place that Spain occupies in international tourism. The Sustainable tourism strategy of Spain 2030 [

37] considers that Spain’s tourism power must contribute to creating a more prosperous, inclusive, and egalitarian society. In accordance with the United Nations concept of sustainability indicated above, tourism, as an economic and social engine, must be a lever for the sustainable development of the territory, contributing to the redistribution of prosperity and wealth, the protection and promotion of heritage and the environment, and the improvement of the quality of life of the citizens.

3. The HoReCa Sector in Spain and the COVID-19

3.1. The Pre-Crisis Situation of the HoReCa Sector in Spain

The HoReCa sector is a relevant economic sector throughout the territory of Spain, with a particularly high weight in the economy of some autonomous communities, such as the Balearic Islands or the Canary Islands, where the weight of gross added value (value of the set of goods and services that are produced over a period, discounting indirect taxes and intermediate consumption) of the hotel industry of the total is around 20% [

38].

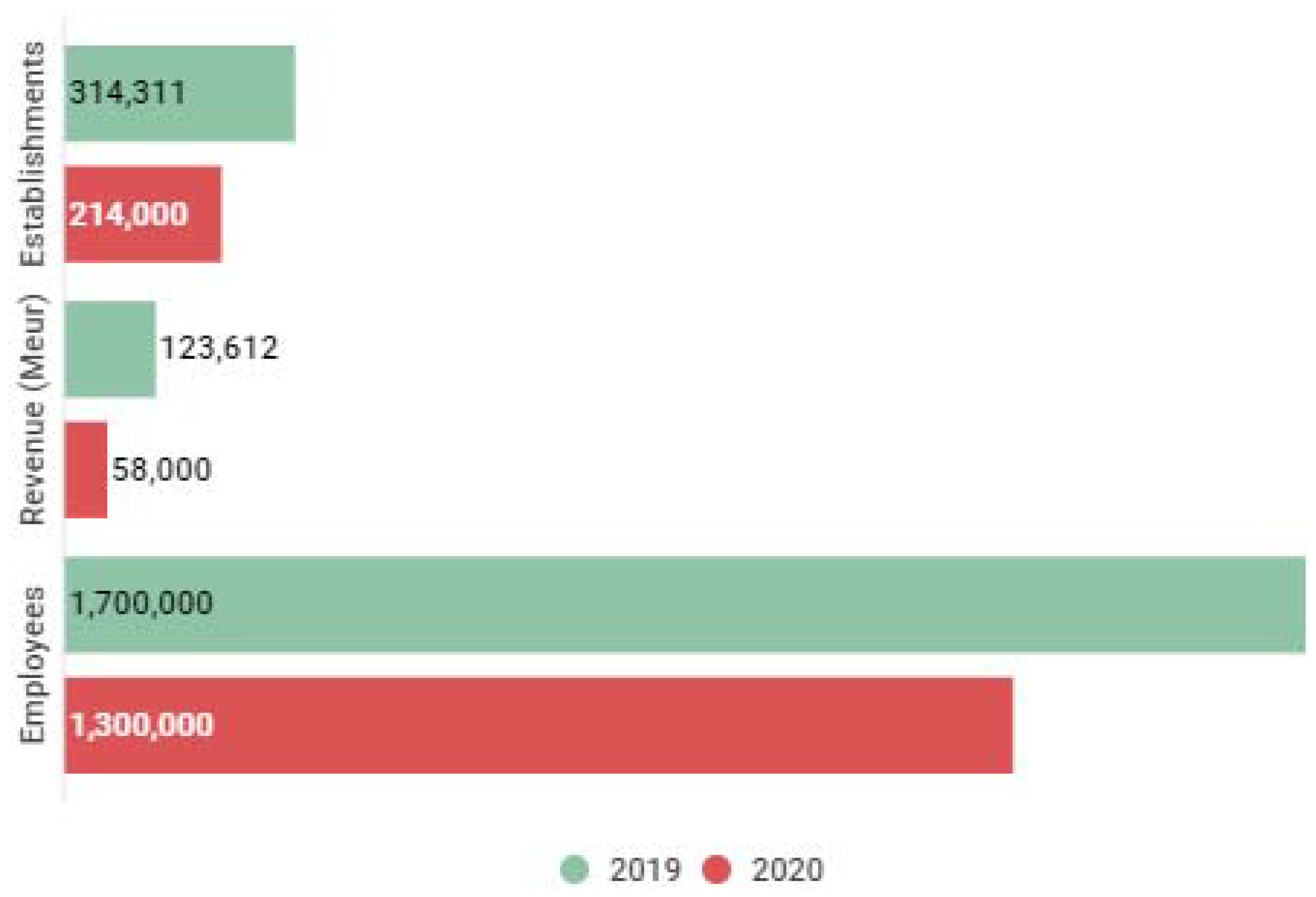

By the end of 2019, according to data from the Spanish Hospitality Business Confederation [

39], the Spanish hospitality industry had more than 314,000 establishments open that employed 1.7 million people, with a total sales volume of 123,612 million euros (6.2% of the GDP of the Spanish economy). Specifically, restaurants, bars, cafes, and pubs employed 1.3 million people, with a turnover of close to 94,000 million euros (4.7% of the national GDP). As all these figures show, the hospitality sector is one of the pillars of the Spanish economy, even more so when considering its relationship with the tourism sector and the indirect employment it generates in other sectors such as food and beverages or distribution and wholesale.

Before the coronavirus crisis, Spanish families used to make a significant amount of their food consumption outside their homes. Specifically, as already indicated, 34.1% of the money spent on food in 2019 (35,962.1 million euros) took place outside the home, according to MAPA data; a figure that Caixabank Research [

40], based on data from the National Statistics Institute (INE), raises to 48,500 million euros, which would be equivalent to 36.5% of the expenditure on food and 8.6% of the total expenditure of households. Specifically, Spanish households allocated 15% of their income to consumption in restaurants and bars, leading the ranking in Europe. This percentage is more than twice the average in the European Union and more than three times that of Germany.

The Spanish restoration said goodbye to 2019 with good omens. According to the data collected in the III Brand Restoration Yearbook in Spain [

41], during that year visits to bars, cafes, and restaurants had increased (+0.9% compared to the previous year) and the average expenditure on each visit had also improved (+0.8%). The year 2020 was looking positive for the sector: cafeterias sold more breakfasts, Spaniards had returned to eat at restaurants with everyday menus, the demand at weekends had increased, etc. In fact, more stores were opening and the supply of restaurants diversified into innovative product and concept proposals, the chains quickly incorporated consumer trends and gradually bet on convenience, multi-channel, digitization, and sustainability.

The arrival of the coronavirus and the strict measures to restrict mobility to combat it radically changed the consumption patterns of families, who stopped frequenting restaurants and other collective food establishments to consume food almost exclusively at their homes.

3.2. Spanish Sector HoReCa Consumption during the Pandemic

The panorama changed radically because of the pandemic: the hotel industry was closed, except for those integrated into sectors declared essential, and consumption was concentrated in households. The evolution of HoReCa consumption in 2020 was not linear but rather behaved like a real roller coaster for the sector due to variations in mobility reduction measures. Consumers had to adapt their habits in each of the phases and acquire new routines, which generated a recovery in the consumption of food and beverages outside the home. Although there are no complete data on the consumption of food and beverages during the year 2020 at the date of this document, the most relevant information about the situation experienced does not lay so much in the increase of food consumption in the private sphere for a circumstantial reason, but rather in the tendency to remain there at the expense of commercial catering.

The figures for the HoReCa channel in 2020, according to the Spanish Hospitality Business Confederation [

39], as of March 2021, amounted to sales of 58,000 million euros, with 214,000 active establishments, as shown in

Figure 2. The number of workers affiliated to Social Security with registration in hospitality again fell below 1.3 million in February 2021, a figure that represents about 300,000 fewer affiliates than in the same month of the previous year, according to data from the affiliation of the Ministry of Labour [

42]. To this drop we must add those workers who are in an ERTE situation, which increased by more than 100,000 in February compared to that in January, approaching the figure of 450,000 workers in this situation.

By activity branches, in the catering sector, there was an average of 1 million workers, 231,704 less than in February 2020, (−17.9%). The year-on-year decline was accentuated in this subsector for the seventh consecutive month. Of the total number of affiliates, 326,988 were in ERTE situation in February (30.9% of the total), 95,000 more than in January; half of the workers who are in ERTE in all sectors (909,661 in total) belong to the hospitality sector [

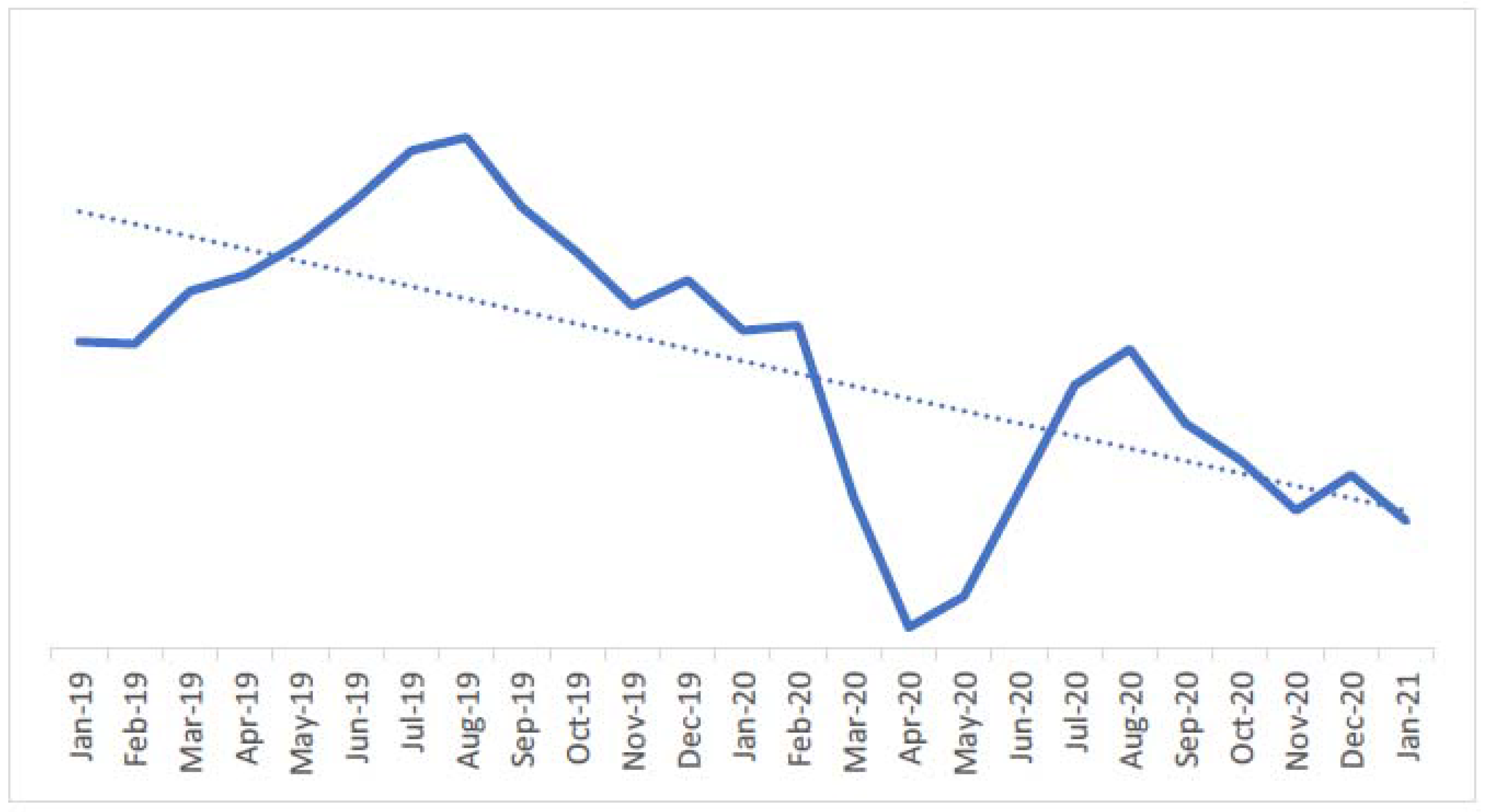

43]. The loss of activity of the hospitality sector in Spain between January 2019 and January 2021 is shown in

Figure 3.

As reflected in a report prepared by the INFORMA DBK Sector Observatory [

44], because of the COVID-19 pandemic, in March 2020 confinement measures and restrictions on openness, capacity, and mobility were adopted to contain the virus. The entire hospitality and the collective market, including the sectors of restaurants, hotels, hospitals, nursing homes, and catering, experienced very unfavourable behaviour during 2020.

Restrictions on the transit of travellers and border closures led to a significant decrease in the number of guests at hotel establishments, whose business volume is estimated to have dropped more than 75%. With the successive limitations and restrictions in time, capacity, and mobility, Spaniards made a total of 2900 million fewer visits to hotel establishments than in the previous year (−39%), according to a report by The NPD Group [

45]. Nevertheless, the evolution of activity in 2020 has been different in the two branches of hospitality activity. In the restaurant sector, which highly depends on national consumption, home delivery services that could be maintained during the months of total closure made a slighter yet notable decline of −43, 6% compared to 2019. This lower drop should not hide the fact that the restaurant sector was also severely penalized, due to the significant contraction in household consumption, the fall of tourism, and the generalization of teleworking. In addition, the closure and reduction of capacity in canteens and cafeterias of companies, schools, and hospitals, the cancellation of most events, and the reduction of the number of travellers caused an important contraction in the catering market in 2020, which approached 40%.

The hospitality subsector was the one that suffered the most from the drop in turnover in the whole of 2020, since the growing evolution of the hospitality industry slowed down after the summer and fell again, unlike most sectors, which generally recovered during the second half of the year, according to the INE [

46]. By autonomous communities, the fall last year was especially strong in the Balearic Islands, with a decrease of 70.8%, and in the Canary Islands, with a decrease of 59.8%, precisely due to the great dependence on the arrival of tourists. In Catalonia, one of the communities with more restrictions, there was a volume of decrease in business of 52.6%, and in Andalusia of 51.7%. In Madrid, on the other hand, the fall was less than 50%. Asturias’ and Extremadura’s hospitality are the ones that have best withstood the crisis, with falls of 38.9% and 38.8%, respectively.

With the de-escalation and the arrival of the new normality, a recovery in the monthly rate was observed from May in the restaurant subsector, together with a moderation in the year-on-year decline in July and August 2020. In any case, this recovery shows large geographical differences, especially in capitals and large cities, which did not manage to return to the volumes of diners of 2019. The decrease was −39% in July and August in the group that includes Madrid, Barcelona, Paris, Lyon, Rome, Milan, Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Geneva, Lausanne, Lisbon, Porto, Brussels, Stockholm, and Copenhagen. On the other hand, the evolution after the first closure had a less negative light in cities located in tourist areas of Europe: −27% in July and −14% in August, in a group that includes the Canary and Balearic Islands, Valencian Community, Andalusia, Bruges, the Belgian coast, Brittany, and the Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts of France, Puglia, Sardinia, Campania, Den Haag, Haarlem, Algarve, Madeira, Valais, and the Swiss Riviera. Consumption comes mainly from national tourism and the local population, which made up for a significant drop in international travellers compared to 2019 (10% in August 2020 vs. 20% in August 2019). However, after the summer, the positive evolution slowed down, declining again in the month-on-month rate and the year-on-year decline until November, when it was accentuated. In December there was again a recovery in the monthly rate, after three consecutive months of decline, with an increase of 25.9% compared to November. The year-on-year fall softened 7 points compared to the previous month, down to −52.9%. In December, for its part, there was an upturn in the monthly evolution of 27.5% in restaurants and of 16% in accommodation. In the interannual rate, the fall moderated in the two subsectors, 6.7 points in catering, down to −45.6%, and 4.1 points in accommodation, down to −75.9%, concerning the same month of the previous year [

47].

3.3. The Challenges of Spanish HoReCa Sector

The III Brand Restoration Yearbook in Spain, prepared by KPMG and presented in October 2020 [

41], includes relevant conclusions from a survey carried out among companies associated with Restoration Brands to assess their vision on the extraordinary situation in which the sector finds itself and on the relevant strategic challenges that lie ahead. In the internal analysis, the respondents indicate as the main weaknesses of the sector their financial situation (89%), issues related to personnel (86%), the strong dependence on the physical premises (71%), and the size of their companies (57%). Its strengths include its value for money (77%), the recognition and appreciation of its brands (69%), the high standards of its gastronomy (60%), and the capillarity and proximity of its stores (57%). Regarding the external environment, companies reflect with their perceptions that the impact of the COVID-19 crisis will not only be temporary but also have structural implications. In this way, they point out that, in the coming years, the most relevant threats to the development of the sector will be the loss of consumer purchasing power (86%), the fall in international tourism (71%), the rigidity of rents (71%), and the impact of teleworking (60%). On the other hand, the respondents rank as main opportunities for the sector the knowledge and direct interaction with the client through digital channels (66%), the acceleration of the development of delivery and take away (60%), the incorporation of technology to improve the experience in the store (51%), and new consumer habits (49%).

As mentioned, the HoReCa sector is particularly fragile and vulnerable to economic cycles and shocks, according to the report by the consultants Ernst & Young and Bain & Company on the impact of COVID-19 on hospitality in Spain [

38]. This is due to several characteristics. It is a highly fragmented sector, made up of small businesses: 70% of the businesses have fewer than 3 employees and more than 40% of the companies have a turnover of less than €200,000 per year; it operates with very low-profit margins: restoration margins are estimated to be around 6%; it has low capitalization levels, with a 34% equity/total assets ratio compared to the 50% average at the national aggregate level; and it has, and this is extremely important given the current situation, little liquidity: 50% of the businesses endure just little more than a month of fixed operating expenses. This sector is, therefore, highly dependent on disposable income, being more profitable businesses than the national aggregate in good times and much more vulnerable in times of crisis.

4. Prospective

4.1. Drawing the Next Future of HoReCa Sector

The future relaxation or elimination of restrictions and the recovery of tourism, if mass vaccination against COVID-19 is effective to stop the pandemic and contain the new strains of the virus that may arise, are not the only factors that will determine the speed and the intensity of the recovery of the HoReCa sector. If there is something structural in the Spanish consumption, it is that the evolution of the catering sector is closely linked to the consumer’s confidence and expectations about the economic situation: when these are high, the demand for food consumption outside the home grows, and when they are low, it decreases.

After the economic disaster caused by the pandemic in 2020, the economic growth forecasted for Spain in 2021 is close to 6% per year, as shown in

Figure 4. It is yet to see whether this recovery of economic activity is achieved and, if so, how intensely.

Despite the context and the difficulties, eating in restaurants remains irreplaceable and basic; it is anchored in the daily life of Europeans, so it is a habit that will continue over time, even if it lives with a certain tendency to spend more time at home and so eating there with more frequency. A study carried out among users of El Tenedor in December 2020 [

48] reveals that among the activities they missed the most during the confinement, going out to restaurants was the first option for 79% of them, even ahead of being with friends and relatives again, with 73%. In the previous phase of this study, developed in June 2020, just after the first wave, 44% of users declared they wanted to return to restaurants, just as before the pandemic began. Consumers value the efforts of hoteliers and believe in the proper implementation of all hygiene and prevention measures in their restaurants. So much so that, even though digital consumption has exploded over the past year and nearly 40% say they do more online booking of restaurants since the arrival of COVID-19, 83% of the respondents plan to continue visiting restaurants, and if circumstances allow, 66% plan to go to restaurants between one and two times a week during 2021, 56% of them allocating a budget similar to that spent in 2020 and choosing restaurants based on price (42%) and gastronomic quality (27%), mainly.

Although these data suggest that the HoReCa sector may go back to growth in 2021 both in terms of turnover and staff and investment, the said growth, although significant, will foreseeably occur on a basis greatly diminished by the sharp falls of 2020. Everything indicates that the evolution will not be enough to achieve a complete recovery. The foodservice market, which includes commercial catering and other smaller channels, such as convenience stores, vending, or company canteens, expects to start its recovery in 2021 with double-digit growth rates, which will oscillate between 16% and 38%. Specifically, the sector has started this year still very affected by the restrictions and limitations imposed to face a possible new wave of infections, with a decrease in sales of around 40% compared to the beginning of 2020, when the crisis had not yet impacted health in Spain, according to data from the market research company The NPD Group [

49]. In this sense, and depending on the speed of recovery, this consultancy’s forecast for 2021 shows sales between 19.5% and 32% lower than those of 2019, the year before the pandemic, depending on the fastest or slowest recovery possibility, respectively. The evolution of the work environment, which currently represents 20.9% of the total billing of food services, including not only the lunchtime meals themselves but all the snacking or breakfast moments related to time in the office or traveling to the place of work, will continue to be very relevant for consumption in this market.

The year 2021 could be a pivotal year for the sector between the crisis and the full recovery of activity. The majority of those surveyed for the III Brand Restoration Yearbook in Spain [

41], 63%, believe that the sector will not recover the existing levels of activity before the crisis until 2022 and even 26% postpone that moment to 2023 onwards. In this context, the surveyed companies expect their growth to develop mainly organically with their own stores (57%) or through franchises (37%). Along the same lines, participants in the 24th edition of the Food and Beverages Meeting, organized by IESE and Deloitte [

50] predicted that the 2019 levels will not be recovered until 2023. According to a survey carried out by the AECOC (Association of Manufacturers and Distributors) with 60 distributors and suppliers of the catering sector, presented at HoReCa Day [

51] on 14 December 2020, the confidence of recovery was also very low: only 6.8% expected to improve their turnover in 2021 compared to 2019, 50% estimated sales between 10% and 30% lower, and 25% a decrease between 1% and 10%; however, 70% believed that there would be a recovery compared to 2020, while 25% preferred to remain cautious in the forecasts, due to the uncertainties in the environment. The AECOC HoReCa sector is also cautious regarding its viability because, despite the loss of business volume, 30% of the companies are still expected to close the year with a profit margin and 20% to achieve a balanced balance.

4.2. Changes in Customer Behaviour

However, unexpected elements such as the increase of teleworking can have a very negative impact on the HoReCa sector. A recent study conducted by the Federation of Independent Users and Consumers [

52] states that 60% of the Spanish working population eat outside their homes; of these, 70% rely on menus. It calculates that the average budget of those who eat outside the home is 259 euros per month, between 150 and 350 euros. Although it is very difficult to know what percentage of consumption in bars and restaurants is due to work, this would be the basis that teleworking can erode.

Based on the Active Population Survey [

53], in 2019, 4.8% of the employed people of Spain usually teleworked. To these, we should add those who did it occasionally, 35%, up to a total of 8.3% (1.6 million). The Valencian Institute for Economic Research [

54] calculated that teleworking affected 34% of Spanish workers during the confinement, that is, 6.8 million people. This same source considers that, potentially, teleworking positions, based on professional qualification and economic sectors, reached 22.3%, and according to the calculations of the Food Service Institute [

55], a 5% increase in teleworking means a turnover loss of 625 million euros for the restaurant sector.

The study “The crisis of COVID-19 in the food and beverage sector. Impact and Future”, prepared by IESE Business School [

56], reveals that the managers of the food and beverage sector do not clearly see that, in the short term, consumers will return to their exit habits in a very active way, indicating a greater probability of an increase of meetings at home, due to a combination of a higher concern for safety and economic reasons.

To this is also added the trend of leisure at home, cocooning or nesting. That is, the option of staying at home during free time. For this there are numerous reasons: personal (social pressure, fears, frenetic rhythms of life, etc.), socio-economic, and technological. Faced with this new post-covid situation, ordinary actions of the past such as going on vacation or eating out will be limited both for “not being able” and “not wanting”, since this “cocooning” leisure trend will be enormously reinforced. On the one hand, there are currently numerous online entertainment platforms, television viewing, video games, and digital platforms with series and movies (HBO, Netflix, Movistar+, etc.) which invite people to spend marathons in front of the screen with their corresponding rise of dopamine. On the other hand, a very varied selection of gastronomic offers at home is growing from the great availability of dishes that are delivered (Glovo, Deliveroo) just by clicking on an application (El Tenedor, JustEat, etc.) together with ordering meal kits, which offer the ingredients and elements that, playfully, help to prepare or finish certain dishes as a new form of effortless leisure. However, against this argument plays the fatigue and desire of the consumer to return not only to the new normal, with the restrictive measures that must be lived within the short- and medium-term, but also to the pre-COVID-situation. This can lead some segments of society to dispense with security concerns, an issue that was clearly reflected during the Christmas and New Year festivities.

The food delivery service has become the main protagonist. The number of companies using delivery platforms has doubled, reaching 64,530 establishments [

57]. This increase in home delivery consumption figures has also generated a transformation of the service to adapt to new consumer trends, giving rise to the creation of the so-called delivery premium (gourmet experiences outside the restaurant), the boom of dark kitchens or kitchen ghosts, and the digital transformation of restaurants through mobile payments, menus with QR codes, remote orders, or online reservations. Spain is, together with the United Kingdom and France, one of the countries with the greatest opportunity for delivery. It is a habit that is not yet well established, but that, nevertheless, is responding positively: 70% of Spaniards tried it in 2020 and 9 out of 10 are satisfied with the experience, according to a study conducted by the consulting firm Kantar and presented during the HIP 2021 event [

58]. This service is valued for its security, simplicity, usability, multi-channelling, and user experience. Restaurants, in this regard, have lost negotiating power, and the price differentials between take-away consumption and delivery tend to disappear. New technological solutions linked to big data and geolocation, among others, are of great importance.

4.3. Changes in Distribution Chains

In the field of gastronomy, the evolution in the marketing strategy in the experiential-leisure aspect has been exponential. Distribution chains no longer limit themselves to selling ingredients or pre-cooked dishes but offer ready-to-eat dishes and even set up spaces for their consumption on the premises, as in the case of Mercadona, combining practicality with fun. In recent months, the term “

mercaurante”, or grocerant, has been coined for this mixed product-ingredient marketing approach with a finished dish, adapting to current consumer trends. The basic need for food is combined with convenience in an age when multitasking and lack of time are recurring elements of daily life. Supermarkets offer an affordable, healthy, and economical answer. The distribution is based on the fact of being present in many spaces, so it is very accessible for the consumer. In these places it can offer a wide range of products and at a very competitive price. Hence, the acceptance of consumers was proving so positive both in the consumption of the premises and in the purchase of the products to take away. Therefore, if we enter a period of deflation or recession, it is foreseeable that this trend in consumption and leisure will be boosted in the coming months. In fact, the supply of prepared and ready-to-eat food from the supermarket, after a brief break in the initial confinement, was reactivated strongly and closed the year 2020 doubling its size, until representing at the end of the year 3% of consumer spending on foodservice [

59], according to data from The NPD Group.

In the future, the client will be different and will demand new adaptations, perhaps more oriented towards the safest, local and proximity products and the design of the merchant will have to adapt to it, both in the ingredients and processing-conservation of the menu as well as in the way it is served on the premises or outside of them: more separated tables, regular cleaning protocols, new takeaway modalities, cleaner and more sustainable patties, etc. It is in this space of home delivery where a new example of cooperation between restoration-food service and distribution-merchant is observed. The delivery companies have joined the two leagues (retail and foodservice) and have put them to compete together, already during 2020. It is a fact that restaurant chains, especially fast-food ones and those that offer daily menus, are being affected by this new merchant competitor. However, the entire sector should be vigilant since supermarkets have great accessibility to the target audience due to having many stores in strategic locations.

Furthermore, distribution chains have not limited themselves to compete with those more popular and accessible in the restaurant sector but have higher aspirations. They have begun to offer gastronomic proposals that are much more elaborate, sophisticated, and with a clear focus on greater added value. They are fully entering the world of gastronomic tourism through offers of traditional dishes of recognized prestige and geography. One of the distribution chains that has already taken action to offer this type of specific culinary offer is El Corte Inglés, which has created an alliance with the Association of Centennial Restaurants and Taverns of Madrid through which they will offer the “most iconic recipes of Spanish culture” [

60]. It can be observed that distribution chains are taking actions not only in favour of selling but also of attracting and retaining customers and are focusing on the gastronomic experience as a strategic pillar to achieve this. How will local, specialized gastronomic and restaurant tourism react in this regard? How will they adapt to this new scenario? Could synergies and new cooperative agreements be generated?

The relationship between the HoReCa channel and retail is evolving rapidly. With Restalia Retail, a new line of business, the restaurant group has begun to sell the most emblematic products of its brands 100 Montaditos and The Good Burger in large stores such as Carrefour and Alcampo and in Glovo’s Black Supermarket, to which other outlets will be added. The company, thus, opts to diversify its business lines and offer new formulas, considering changes towards household consumption. To do this, it offers on the shelves a careful selection of products at a smart cost price, the same ones that can be found in its stores. In this way, now any consumer will be able to enjoy, and even easily prepare, Restalia experiences at home. The commitment to retail benefits, a priori, the HoReCa line since the commercialization of Restalia products in supermarkets, is also designed to direct traffic to their stores since the sale of these products will also help many customers to discover brands and will encourage them to enjoy these menus in the atmosphere of their restaurants. Restalia is not the only restaurant group that is committed to retail; the Goiko hamburger chain has also decided to take the ingredients of its popular hamburgers to supermarkets so that consumers can prepare them to their own liking at home [

61].

The virtual restaurant business is also new. The hospitality divisions of Campofrío Smart Solutions and Pescanova Fish Solutions have joined the Sagar restaurant group to enter the virtual restaurant business. According to Europa Press [

62], Napoletta de Campofrío and The Hot Dog Corners by Oscar Mayer and PeZcado Capital de Pescanova are new virtual establishments that are already available in a pilot test in Madrid. In this way, Campofrío and Pescanova are adapting to new consumption patterns through a profitable and replicable business model that has first opened in Madrid and then will be exported throughout Spain to respond to the more than two million new consumers that want to enjoy the restaurant at home.

Finally, in forecasting the evolution of HoReCa consumption, it is also necessary to consider the growing weight of the consumption of fast food prepared in commercial establishments in recent years, both locally and at home, due to its prices and the possibility of consumption in multiple spaces, because they are better suited to situations of economic downturn and limited mobility. The turnover of the fast-food sector in Spain in 2019 stood at 4035 million euros (a growth of 5.9% compared to 2018), according to data from the DBK Sectorial Observatory [

63], which represents 16% of restaurant sales commercial. Hamburger restaurants accounted for most of the market with 54.9% of sales, followed by pizzerias with 18.2% and sandwich shops with 14.6%. Home sales already stood at 660 million euros in 2019, 16.35% of sales, with an annual growth rate of 17%, compared to the 4% increase in counter purchases.

4.4. Scenarios in HoReCa Sector

The European Institute of Innovation & Technology Food, in collaboration with Lantern, has drawn four possible future medium-term scenarios for European agri-food consumption and describe how each of them would affect agricultural production, processing, and distribution of food, on-demand, and the HoReCa channel [

64]:

Full recovery from the reality of the pandemic. This is the most optimistic scenario and possibly the least likely. It would be characterized by the recovery of consumers’ confidence and demand and, therefore, the disappearance of production surpluses. The agri-food industry would return to the previous situation, without making relevant investments in protection against new pandemics. Large distribution would continue with its current system, coexisting with an acceleration of the electronic purchasing channel. The HoReCa sector would return to pre-pandemic levels, but according to the lessons learned during the confinements and the states of alarm, it would promote products with more added value, strengthen the connection between the various sectors of the distribution and consumption chain, and make massive use of information technologies in communication with customers and suppliers.

Emergence of a new type of consumer. Consumer preferences and demand would have changed in line with the consolidation of emerging trends that have accelerated during the pandemic. The demand for healthy products, with high nutritional value, of sustainable and ethical production and transformation, and with a preference for local origin, would grow. The HoReCa sector would not regain its pre-crisis market share due to the increase in home cooking, consequently accompanied by the higher demand for basic foods and prepared products and the decrease of foods with greater added value.

New set of rules. The threat and the reality of the reactivation of health crises continue to be seen on the horizon. Faced with this situation, the retail trade should be fully integrated into the electronic sale of food to stay in the market. The HoReCa channel would suffer negatively from the persistent policies and contingency measures, having to adapt to the new forms of consumption at home, mentioned in the trends chapter. Reduced demand and depressed global markets would increase the risk of protectionism and the imposition of retaliatory tariffs of countries to support their producers. The volume of world food trade would decline significantly. However, the processing industry would benefit from lower raw material prices.

Distortion and disruption. This is the most pessimistic scenario. Containment measures for the pandemic would totally disrupt labour flows and the HoReCa sector. The demand would be reduced, due to the reduction of the income of the families. E-commerce would take over retail, destroying a part of the retail fabric. The decrease in demand would cause excess supply and, therefore, a fall in the price of basic products, which could make part of agricultural production unviable. Consequently, investment in industrial and logistics facilities would be reduced.

Concerning the short term, the information currently available gives us a glimpse of four potential scenarios: old normality, new normality, change, and abnormality, each of them having an impact on economic activity in general and on the HoReCa sector in particular [

65].

The old normality. This scenario is based on the desire of society that “everything is as before.” It is favoured by the generalization of vaccination, which prevents new waves of the pandemic. There is a relatively rapid return to normality in the economy, including international trafficking of people and goods. It is characterized by an aspiration to resume social habits before the pandemic. The restaurants are full; both supply and demand seek to recover “lost time” as soon as possible. Consumption and competition grow, establishing fierce price wars. Some technological advances that have been introduced rapidly during the crisis are consolidated, especially digitization, and, therefore, a new value chain. This trend makes it easier to obtain consumer data that allows the offer to be segmentalized and personalized more effectively. Delivery is here to stay. Consumer behaviour is like that of the times before the crisis, but the health concern is transferred to food safety, increasing the demand on aspects such as traceability and transparency throughout the chain and hygiene measures at the points of consumption with an impact on the value chain (single dose, etc.). This generates contradictions, which is why new proposals are required; for example, single doses contrast with sustainability and the desire to eliminate plastic packaging.

The new normality. It means “to watch one’s steps” after what happened. Recovery is slow and specific peaks of the virus force enough restrictions to be maintained on mobility and other social habits that facilitate close contact with people. These restrictions have a high negative impact on tourism and, therefore, on catering. The number of suppliers per company increases. Supply security takes precedence over rigid streams of cost savings such as the JIT (just-in-time) method. Supply problems are common, as they are regular shutdowns due to employee infections. Organizations identify new supply sources for the products or services on which they depend so that if COVID-19 disrupts supply chains, they have a plan B. In addition, the supply is flexible in case the stocking of a key item is interrupted. The safety of factory workers is prioritized, in part due to the risk of closure in the case of an outbreak. There is lower demand due to economic crisis. There are closures, mergers, and acquisitions of SMEs by large organizations. The restrictions imply the generalization of low touch economy: teleworking, tele-education, etc. Strict controls are implemented on all actors in the value chain, facilitated by technologies such as blockchain. Cooking at home becomes more than just a hobby in the “new normal.” All trends related to home consumption prevail: take away, delivery, etc. New start-ups emerge to deliver food and daily menus to the home. There is a boom in merchants. Packaging is once again perceived as a guarantor of food safety. Local agents appear as cold storage nodes. Collaboration between actors along the value chain is intensified to respond to a demand and to diversify supply. The consumer adopts a conservative stance, with an impact on the average ticket of each drink and a focus on the price. You can witness a neighbourhood restaurant boom and a return to the consumption of more traditional products. There is also a lower consumption of fresh products for fear of contamination and higher prices. Processed foods increase their market share. Government restrictions and consumer hesitancy create a large surplus of high-value products.

The change. The pandemic is under control, but it is reluctant to leave us. People get used to living with the virus and so adapt their behaviours to it. Occasional outbreaks still occur. Companies operate with a high level of uncertainty and forecasting is difficult. This also affects consumption levels, as the duration of the pandemic is unclear. To deal with this uncertainty, organizations make greater use of temporary staff or external service providers to respond quickly to changing business conditions and increasing or decreasing staff as needed. The idea of betting on a new digital and sustainable model is generalized. There is a rapid emergence of new businesses and disruptive technologies. Big data analytics and artificial intelligence emerge as prediction tools for resilience and improved distribution. The distribution chains are shorter. There is an expansion of investments guided by the principle of sustainability: sustainable mobility, renewable energy, rehabilitation of spaces, research and innovation, recovery of biodiversity, and circular economy. Discard and surplus exchange platforms are created for their revaluation. There is a zero-waste packaging boost (bioplastics, edible films, etc.). Local production and a return to the rural world are revalued. This tends to direct marketing from the farmer or rancher; since the channel is best suited to high-value products rather than fresh or short-live products, its growth will depend on the progress of online platforms and last-mile initiatives. Consumers begin to act “normal” as the situation allows, but new consumer behaviours will likely emerge as well, with a focus on avoiding waste, returning to what is known, and personal care. People pay more attention to their health and well-being, focusing on boosting immunity through more exercise and healthy eating, as a form of preventive medicine.

The abnormality. The pandemic becomes endemic. Successive mutations of the virus render vaccines ineffective. Home, local, regional, or national confinements are common. There are difficulties for the mobility of people and international trade. The health situation has a great impact on domestic economies, due to the massive closures of companies. There is a fall in international tourism. Great recession and social tension arrive. Distrust is generalized. The consumer focuses on the price and the most basic products in the shopping cart. The purchase of ultra-processed foods is widespread. There is a reduction in the consumption of meat, fish, and fruit. Consumption of single-use plastics is increasing. The market is dominated by private labels. Bulk consumption is back.

5. Towards a New Supply Chain in the HoReCa Sector

At this point, no one doubts that the current complex situation will have structural consequences on restoration, significantly accelerating and shortening the development times of some of the incipient trends that were already observed and generating new challenges. The situation, therefore, requires a combination of highly tactical measures, forced by circumstances, with a more strategic vision and decisions that will require courage and investment, and this is how the sector understands it. As an example, and in advance, data from the III Brand Restoration Yearbook in Spain [

41] show the following: 60% of the restaurant chains qualify the acceleration of the development of delivery and take away as an opportunity. The opportunity for the sector will lie in a better homemade experience, diversifying the assortment, improving the value for money, and continuing with the digital transformation.

Because of the above, and as a summary, it is possible to identify four trends that “have come to stay” in food consumption, regardless of the scenario that is imposed: eating at home, cooking at home, delivery, and healthy nutrition. The confluence of all these changes and trends can have an impact with such intensity that it can even configure a new supply chain in the hospitality sector, as shown in

Figure 5.

Therefore, new actors appear, while others reposition themselves, and the access routes to the final consumer increase exponentially. It is expected that the “classic” formula, going to a HoReCa establishment to consume in it, still maintains a majority prevalence, but the growing trend towards consumption at home, widely described throughout the article, totally revolutionizes the supply chain, generating new opportunities but also integrating new requirements (speed, flexibility, transparency, etc.). The impact of these changes from the perspective of sustainability, in its triple focus, has yet to be quantified.

6. Conclusions

The HoReCa sector is particularly fragile and vulnerable to economic cycles and shocks, as the current health pandemic has shown. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, in March 2020 confinement measures and restrictions on openness, capacity, and mobility were adopted to contain the virus. The entire hospitality industry and the collective market, including the sectors of restaurants, hotels, hospitals, nursing homes, and catering, experienced very unfavourable behaviour during 2020. This problem is not only evident in the hospitality industry; the earthquake that is shaking the sector is also causing strong tremors in the food and beverage industry. The question is whether the year 2021 could be a hinge year between the crisis and full recovery of activity for the HoReCa sector.

The public information sources available have proven useful and sufficient to analyse and evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 crisis in the HoReCa sector in Spain in research carried out in the year of the emergence of the pandemic, even when there is still uncertainty about its duration. Likewise, those sources combined with fieldwork with professionals and clients of the sector allow prospective reports to elaborate on future consumption scenarios, considering the possible evolutions of the pandemic and its effects on consumers. At this point, scientific research faces three challenges.

The first challenge is to measure, once the statistical data for the whole year of 2021 is available, the impact of the sanitary pandemic in the economic results in the HoReCa sector in general and in each subsector. A comparison is urgently needed with the previous years of expansion in the various countries of Europe and inside each country, with the purpose of properly quantifying the economic consequences of the sanitary crisis and of guiding the public policies needed to restore the sector. The projection of scenarios does not explain a reality based on scientific and contrasted evidence, but must be understood as a management tool to help businesses and government officials of the sector to reflect and take strategic, tactical, and operational strategies.

The second challenge is to discover and interpret through qualitative investigations based on interviews and discussion groups with experts, businesses, and users whether the detected changes in the consumers of the HoReCa sector during the pandemic have become dominant consumer trends. Eating in restaurants remains irreplaceable and basic; it is anchored in the daily life of Europeans, so it is a habit that will continue over time, even if it lives with a certain tendency to spend more time at home and so eating there with more frequency. However, it is not clear whether, in the short term, consumers will return to their habits outside the home in a very active way. The pandemic has accelerated some trends in food consumption that began in previous years while causing changes that point to the emergence of new ones, and only time will tell if they consolidate. It should also be taken into account that the probability of maintaining a recently acquired consumption habit will increase if it is aligned with the evolution of consumption trends. We are immersed in hard times and the evolution of the pandemic is uncertain. The trends described will or will not be consolidated depending on the scenario that finally arises. Future research work should delve into their impact and the link between them, as well as into the disruptions that they will undoubtedly end up causing.

Finally, the third challenge is to confirm if the new trends will affect the economic performance of the HoReCa sector in general and, what is more relevant, if they will cause changes in the logistic chain from producer to consumer in the sense suggested above. The applied nature of the investigation in tourism and hospitality requires not only an understanding of the studied events and reality, but also the identification of the changes in the environment and the analysis of their impact with the object of guiding and supporting the business projects and public policies of the sector. Prospective sciences, business strategy, and public politics shape the four vertexes that must cooperate in the development of any economic sector in a VUCA environment as the current one, characterised by volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity. In this sense, situation studies with an approach typical of competitive intelligence, as the one presented, prove useful when they provide early warnings of changes that can lead the way of new investigations.