Abstract

Global use of carsharing has increased. The dominant model is station-based carsharing, but free-floating providers are continuously increasing their businesses volumes. Carsharing customers have been described as environmentally conscious with a high preference for mobility providers who show responsibility and trustworthiness. This generalization of usage determinants appears to be questionable given the background of current market developments. Existing research in the area is lacking a context-sensitive view of the antecedents of potential carsharing usage. Do environmental concerns and trust have similar effects on usage intention of carsharing, when free-floating providers implement business models that are more flexible, digital, and sophisticated? Using a standardized online survey, this study paper applied a framework adapted from the Theory of Planned Behavior (ToPB) that included the constructs of trust and environmental concern. The focus was on Share Now and Stadtmobil, which are the largest free-floating and station-based providers, respectively, in Germany. Using structural equation modeling, the study explored potential perception differences between both business models among German consumers. Although not significant, results indicate slightly higher total effects of environmental concern and initial trust on the usage intention of station-based compared to free-floating carsharing. Depending on the type of carsharing, different priorities should be set in the respective business model.

1. Introduction

Although sharing economy is generally considered to be an umbrella term for transactions, such as access-based consumption, collaborative consumption, or commercial sharing systems [1,2,3], a common objective of the associated business models appears to be making assets available to a larger user community [4]. Shared mobility is part of the sharing economy, and applies concepts for the common use of mobility devices or services [5]. These may be cars, bikes, or e-scooters, or the sharing of passenger rides or delivery rides [6,7]. The concept is not new: the first services, such as peer-to-peer ride sharing, appeared in the U.S. and Europe in the 1980s.

Shaheen and Chan [5] developed a comprehensive classification of existing shared mobility concepts. In recent years, shared mobility markets have been driven by the development of various carsharing solutions. As of 2019, carsharing was offered in over 50 countries, and over 200 carsharing providers were operating in over 3000 cities [8]. Approximately 2.5 million carsharing users were registered in Germany in 2019 [9]. These users are given access to vehicles on an “as-needed” basis, which underlies a pay per use and/or membership-based pricing model [5].

Since the first documented carsharing activity in Switzerland 1948, various forms of carsharing business models have been developed [10]. Station-based carsharing has been continuously implemented for the past 30 years, and is also referred to as “two-way”, “round-trip”, or “traditional” carsharing [11]. Users of station-based carsharing can choose vehicles distributed among fixed stations within the operating area. Users must reserve a vehicle, pick it up at a specific station, and return it to the same station or leave it at other defined stations within the system [6,11]. Operators of station-based carsharing include are Flinkster, Zipcar, and Stadtmobil [12]. Free-floating carsharing differs because it allows users to return the car to any location within a pre-defined operation area [13,14]. In most cases, free-floating platforms provide users with GPS tracking of the available cars and a short-term reservation option [15]. Operators of free-floating carsharing include Share Now, Witcar, or E-Car [8]. Another business model for carsharing is peer-to-peer carsharing, in which the company only operates the platform and does not provide the utilized vehicles [4]. Because the basic function of peer-to-peer operators differs significantly from those of station-based and free-floating carsharing, peer-to-peer models are not considered within this paper.

Previous scientific contributions have focused on the usage patterns of carsharing services [16]. A large amount of research has been conducted regarding drivers and the determinants of their intention to use carsharing services [17]. Most of those studies have attempted to categorize carsharing users and construct user segments according to these acceptance determinants [6,18]. Numerous approaches have attempted to categorize carsharing users based on sociodemographic criteria such as age, gender, or income [18,19]. The acceptance determinants are most often instrumental attributes, such as price or special availability of parking spaces [20]. In addition, analysis has also been undertaken of personal values and psychological variables, and that manner in which they shape attitudes to carsharing and using intention [6]. Paundra et al. [20] investigated so-called “psychological ownership” as a factor that has a potential influence on the adoption of carsharing.

Regarding the psychological, personal, and value-related variables, environmental concern and trust, in particular, are frequently discussed as being antecedents to the intention of using carsharing [19]. Particularly when replacing privately owned cars, carsharing models have proven to significantly contribute to reduced emissions [21]. Greenblatt and Shaheen [21] showed that potential savings of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions were 30–40%. The research of Burkhardt and Millard-Ball [22], and Costain, Ardron and Habib [23], found that carsharing customers were environmentally conscious and willing to choose environmental friendly mobility alternatives. Although environmental factors have relatively small effects on behavioral intentions [14,24], environmental concern is one of the main constructs considered in the analysis of customer views of carsharing business models [19,25]. Previous studies have also aimed to understand the relationship between environmental concerns and various forms of behavior [26]. The construct of trust appears frequently in corresponding research. This concept can be understood as the human ambition to accept a vulnerable position regarding a technology or service in the expectation of positive future behavior [27,28]. Accordingly, a behavior can be significantly strengthened by a positive attitude of trust with regard to the respective context. The literature reveals trust is a construct with a central impact on adoption intentions and consumer behavior with regard to technologies and services [27,29,30,31]. The lack of trust is recognized as a barrier for the diffusion and market success of mobility services [32,33]. Consequently, trust is seen as the main construct that may potentially influence the using behavior of carsharing services [1,32]. Trust may affect the attitude toward the operator, the platform, or the service itself [32]. Investigations of the constructs that influence the intention to use carsharing services have not generally differentiated between carsharing business models. Findings have either been derived for carsharing or the sharing economy in general [3,34], or researchers have focused on one or the other concept, and analyzed its usage antecedents [1,35]. In addition, station-based carsharing is a comparatively more frequent subject of research [36]. However, research findings on the different characteristics and user types show significant differences between station-based and free-floating carsharing [37]. The personal car-ownership percentage of free-floating users is significantly higher than that of station-based carsharing members [16,38]. The users of free-floating carsharing also see private cars as a status symbol, whereas station-based users are less likely to agree with this statement [6]. Emphasizing the role of personal acceptance drivers, such as trust and environmental concern, researchers question if technical developments, including more digitalization in carsharing business models, necessarily enhance personal user compatibility [6].

A research gap exists regarding the identified specifics in user personalities. An analysis of the determinants of carsharing usage intentions with respect to the specific contexts of the free-floating and station-based carsharing business models appears to worth investigating. It is expected that business model-related differences would require more context-sensitive marketing for different carsharing services. Our two research questions are:

RQ1: Which factors influence the intention to use free-floating carsharing compared to station-based carsharing?

RQ2: How does the effect of environmental concern and trust on intention to use differ between free-floating carsharing and station-based carsharing?

To address these questions, the remainder of this paper is structured as follows: First, a structured review of studies that have investigated the usage intentions of carsharing services is provided. Second, a conceptional model is derived referring to the classified contributions on carsharing acceptance, and research hypotheses are addressed with regard to the constructs of trust and environmental concern. Third, results are presented based on structural equation model analyses of each of the two carsharing business models. Finally, the impact of the findings relating to the theory of carsharing usage is discussed; furthermore, practical recommendations for station-based and free-floating operators are provided. Areas of future research on the topic and limitations of the study are also addressed.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Existing studies on the usage and using intention of carsharing can be roughly classified as 1. studies on functional attributes and usage patterns of carsharing; 2. studies on carsharing user segments; 3. studies on user acceptance of carsharing. These are discussed in this section.

Studies on functional attributes and usage patterns of carsharing analyze the actual usage behavior of consumers that are members of carsharing services, in addition to the functional aspects and attributes that influence that behavior. Efthymiou, Antoniou and Waddell [39] conducted a comparison study to determine the functional factors that customers consider when using either shared bikes, shared cars, or shared electric cars. Zoepf and Keith [35] conducted a discrete choice survey in North America. They analyzed the potential decision behavior of customers for different cars based on vehicle type and distance to the parked vehicle, referring on a station-based carsharing setting. Wang et al. [40] investigated average trip distances of Chinese customers of free-floating services, in addition to the influence of policies that restrain the purchase of cars on that behavior.

Studies on carsharing user segments aim to classify customers according to personal or behavior-oriented criteria. Schmöller et al. [34] analyzed the booking data of a German free-floating operator to identify booking patterns and requirements of fleets and supply management. Accordingly, they segmented customers with regard to booking behavior, sociodemographic variables, and external framing conditions, such as weather in potential booking timeslots. Greenblatt and Shaheen [21] described and segmented users of station-based carsharing according to owning structures of different mobility devices. Burghard and Dütschke [6] found that carsharers were a sociodemographic specific group. Their segmentation revealed that carsharing with electric vehicles is particularly highly appreciated by younger people who live as couples without owning a car, or young families using carsharing in addition to a privately owned car [6].

Studies on user acceptance of carsharing focus on the antecedents and determinants of the intention to use, and using behavior of different types of carsharing business models. Kilbourne and Pickett [25] addressed the potential effects of environmental beliefs and environmental concerns on different forms of direct and indirect behavior. This effect has been widely examined in studies on mobility services in general and, in particular, on carsharing approaches. Schaefers [14] investigated the motives of carsharing usage based on a qualitative means-end chain analysis among members of U.S. carsharing services. He derived a motive pattern with four potential motive categories, namely, value seeking, convenience, lifestyle, and environment. In addition, Hamari, Sjöklint and Ukkonen [2] identified motive categories to explain why people participate in collaborative consumption such as carsharing. Their identified categories were sustainability, enjoyment, reputation, and economic benefits. Balck and Cracau [3] conducted a comparative analysis of motives to share different assets. Their results recognized the general dominance of costs and the relative dominance of the environmental motive with respect to carsharing compared to sharing accommodation, commodities, or clothes. Gao, Jing and Guo [32] emphasized the role of trust in the acceptance and using intention of carsharing services. They stated that trust can help consumers to overcome perceived risks and uncertainty when using carsharing. A similar study on the effect of trust on carsharing usage was conducted by Liang, Li and Xu [1]. Fleury et al. [24] applied the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), which they extended using perceived environmental friendliness, to evaluate the acceptance of corporate carsharing services in France. Burghard and Dütschke [6] found that compatibility with daily life is a highly important construct that influences carsharing acceptance. Müller [41] compared the acceptance determinants of electric vehicles, autonomous vehicles, and carsharing. Applying an extended Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to customers in China, U.S., and Europe, he identified a relatively high influence of perceived ease of use on the usage intention of carsharing [41]. Wang et al. [42] focused on the effect of environmental awareness and perceived usefulness on the acceptance of ride-sharing.

In addition to TAM and UTAUT, most researchers analyzing the intention to use carsharing services have based their investigations on adapted frameworks of the Theory of Planned Behavior (ToPB) [43,44]. ToPB is a basic psychological framework that explains behavioral intentions in general, and is a suitable framework for the analysis of the antecedents of the intention to use carsharing services. Witzke [17] applied ToPB to analyze carsharing acceptance among young consumers in Germany. Using the ToPB, Kaplan et al. [45] explored behavioral factors that underlie tourists’ intentions to use urban bike-sharing in Denmark. Haldar and Goel [46] applied the framework to an acceptance analysis of carsharing apps. Zhang and Park [47] used ToPB to identify the factors that affect the usage intention of carsharing services in South Korea.

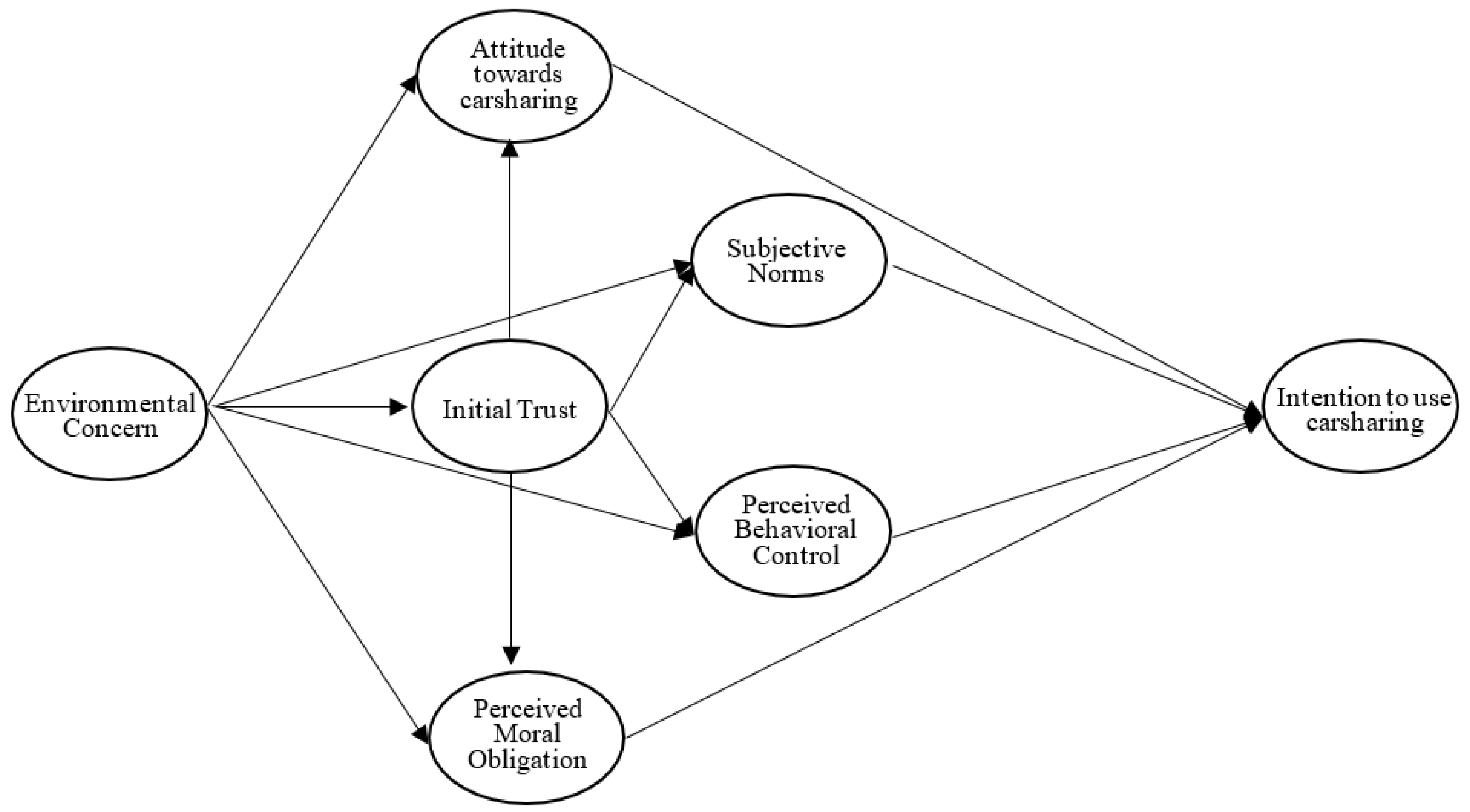

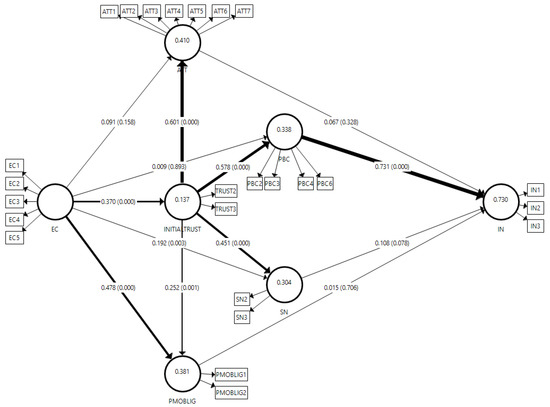

Taking these contributions into account, an extended version of the ToPB model proposed by Chen and Tung [48], which specifically emphasizes the role of environmental concern (EC) in the usage intention (IN) of sustainable services, was used in the current study. This model provides a suitable framework for this study. Environmental concern is highly discussed in the literature as a potential personal and external antecedent of carsharing usage [19,25]. This model is complemented by the construct of trust. The literature indicates that trust is another key construct that affects acceptance and usage intentions of mobility concepts [27,32]. Trust is basically understood to be an evolving construct, which develops dynamically during an interaction [49]. The previous research did not conduct a user experience study in which the experiential carsharing setting may influence the level of trust; furthermore, the survey design also involved subjects without practical carsharing experience. Therefore, we consider trust to be a more “long-lasting” variable, and an initial parameter that determines the view of specific carsharing business models. We labeled this parameter initial trust (INITIAL TRUST), which mediates between personal environmental concern and the established ToPB variables in the model [30,50,51]. Considering the characteristics of carsharing services, the four constructs directly determining the intention to use in the ToPB model of Chen and Tung [48] were further specified as follows. Based on the attitude towards carsharing (ATT), Han, Hsu and Sheu [52] evaluated the extent to which users considered the carsharing services to be favorable, enjoyable, and desirable. Subjective norms (SN) have been used to investigate how the social environment of a single person affects the value of her/his usage of a certain carsharing business model [44]. Referring to scales developed by Dean, Raats and Shepherd [43], and Chen and Peng [44], the perceived behavioral control (PBC) was analyzed as the personal ability and opportunity to use a specific carsharing service. Finally, the perceived moral obligation related to an individual’s perception of the need to treasure natural resources was integrated [53]. The current study applied the conceptual model (see Figure 1) to the investigation of the usage intentions for station-based and free-floating carsharing.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model. Source: own study based on Chen and Tung [48].

This model provides a solid basis to answer the research questions. The first research question (RQ1) is more explorative in nature and addresses potential differences in factors that influence usage intentions of station-based and free-floating carsharing in general. Considering the second research question (RQ2), which specifically refers to the influence of initial trust and environmental concern, the following differences were expected, particularly with regard to the different characteristics and user types described in the literature for station-based and free-floating carsharing:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Initial trust has a higher influence on the potential usage of station-based carsharing than that of free-floating services.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Environmental concern has a higher influence on potential usage intention of station-based carsharing than that of free-floating services.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Survey Design

Two standardized online surveys in Germany were conducted. The full dataset was made freely available by the authors. In the first survey, the intention to use free-floating carsharing was evaluated by reference to Share Now, the biggest free-floating operator in Germany [54]. In the second survey, the intention to use station-based carsharing was evaluated by reference to Stadtmobil, the biggest station-based operator in Germany [54]. Respondents were recruited through an industrial/academic network structure in the state of Baden-Wuerttemberg (over 10,000 company members of Baden-Wuerttemberg Cooperative State University). These company representatives were asked to take part in the survey and to redistribute it within their personal environments. Final respondents were either users of the related carsharing service or had comprehensive knowledge of the investigated business models. The participants were asked to rate each question on a 5 point Likert scale (usually 1 = fully disagree, 5 = fully agree). The items and their associated constructs are shown in Table 1. The total sample size was 277, comprising 103 respondents for free-floating Share Now carsharing and 174 for station-based Stadtmobil carsharing.

Table 1.

Item summary—questionnaire for Share Now group and Stadtmobil group.

3.2. Measurement

Prior to detailed group-specific comparisons, predictor and outcome variables were examined for patterns and extent of missing values using the four-step approach described by Hair et al. [55]. The percentage of missing values per case ranged from 0 to 44.4%. Based on their recommendation, the decision was made to delete observations for which up to 50% of entries were missing, and to exclude 14 cases with missing data in the target outcome construct usage intention (INT1, INT2, and INT3). The percentage of missing values across the 36 variables varied between 0 and 38%. After examining the patterns of missing data and the extent to which missing data were reduced, three items with the highest shares of missing values (TRUST1, PBC5, and SN1) were removed. This discard increased the number of cases with complete data by 22 to a total of 125. The final data set contained 33 variables and 262 observations. There were 98 participants in the Share Now group (51 females, age: M = 40.91 years, SD = 13.60) and 164 participants in the Stadtmobil group (68 females, age: M = 44.07 years, SD = 16.01).

Little’s test of Missing Completely at Random was performed to elaborate the type of missingness and revealed a significant result, χ2(1903, N = 262) = 2062, p ≤ 0.05, thus indicating data were not missing completely at random [55,56,57]. This result required an in-depth analysis. Therefore, the non-respondents were compared to the respondents using logistic regression analysis with the missing data dummy variable as the outcome were compared. (We computed binary indicator variables for all variables with missing data (e.g., for TRUST2) that separate the participants with missing values (coded as 1) from the participants with observed values (coded as 0). The indicator variables were then used as dependent variables and all remaining model variables (except for ones with a high share of missing values) were used as predictors in the logistic regression analysis ([55,56]).) Against this background, the impact of other variables in the database on the missingness in the dependent variable [55,56] was able to be assessed. The analyses revealed that the likelihood of nonresponse depended on the included predictor variables. This allowed us to conclude that the “missing at random” assumption is reasonable. The commonly used k-Nearest Neighbor procedure as implemented in the VIM 5.11 package [58] to impute the missing Likert-type data was applied. The decision for k (the number of neighbors) = 11 refers to the widely accepted rule of thumb, according to which the optimal number of k can be determined using the square root taken from the number of valid, i.e., complete, records (e.g., [59]).

Considering the exploratory research setting of this study, the multigroup analysis (MGA) between the two carsharing types drew on partial least squares structural equation modeling using SmartPLS 3.3.0 [60]. The bootstrapping procedure referred to 5000 subsamples and was performed for significance testing (no sign change option) [61]. Each of the eight constructs were specified as common factors and measured reflectively. In the assessing of convergent validity, three indicators were removed from the initially specified measurement model of both groups due to loadings below the recommended threshold value of 0.7 [61]. After the removal, all indicator loadings were significant and larger than 0.7 (see Table A1). A second aspect of convergent validity refers to the average variance extracted (AVE). In both groups, the AVE scores clearly exceeded the minimum threshold of 0.5, thus indicating that all of the reflectively measured latent variables explained, on average, over 50% of the variance of their items, respectively (see Table A1). To evaluate discriminant validity, the Fornell–Larcker criterion was first considered. According to this criterion, a latent construct should have more common variance with the associated indicators compared to the other latent variables specified in the model [61]. This requirement was fulfilled because all AVE values were larger than the observed inter-construct correlations (see Table A2). Secondly, discriminant validity using the heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) was evaluated. In both groups, the HTMT values were significantly below the threshold of 1, and the value of 1 was also not within the 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals; thus, the measurement models met the recommended rule of thumb (see Table A3 for the Share Now group and Table A4 for the Stadtmobil group) [61,62]. Furthermore, in both groups, the indicator loadings were larger than the cross loadings [62]. Based on these three criteria, it was concluded that discriminant validity was achieved, thus indicating a satisfactory extent to which the eight factors differed from each other [62]. Furthermore, construct reliability was assessed. The analyses revealed acceptable results for both groups (min. Cronbach’s α Share Now > 0.83, ρA Share Now > 0.84, min. ρC Share Now > 0.92; min. Cronbach’s α Stadtmobil > 0.76, min. ρA Stadtmobil > 0.80, min. ρC Stadtmobil > 0.89) (see Table A1 for fully reported results of internal consistency) [55].

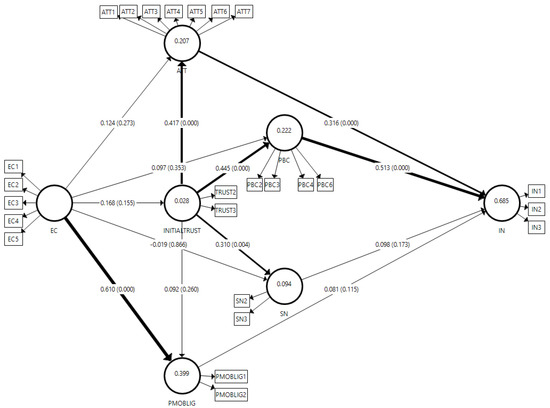

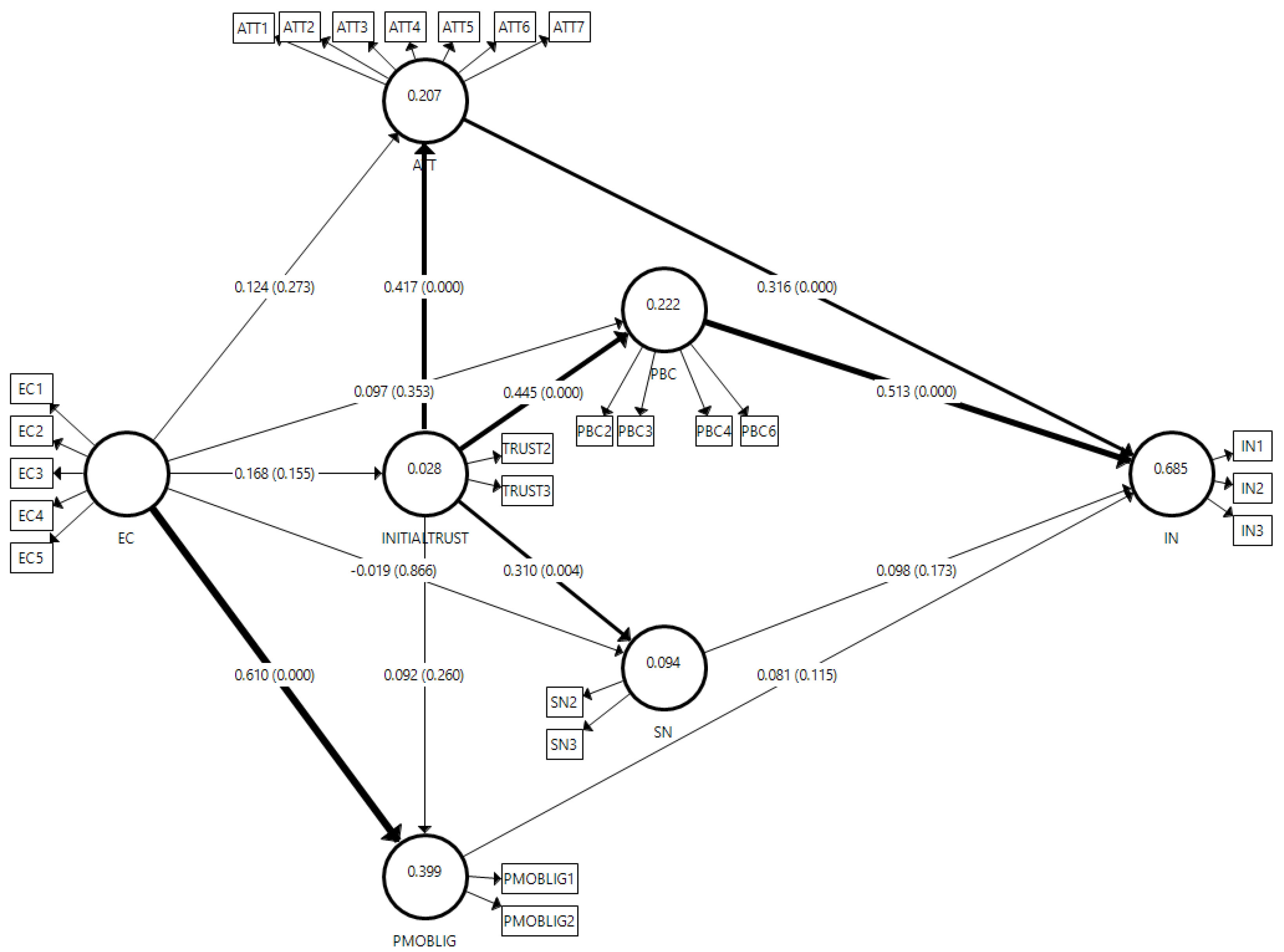

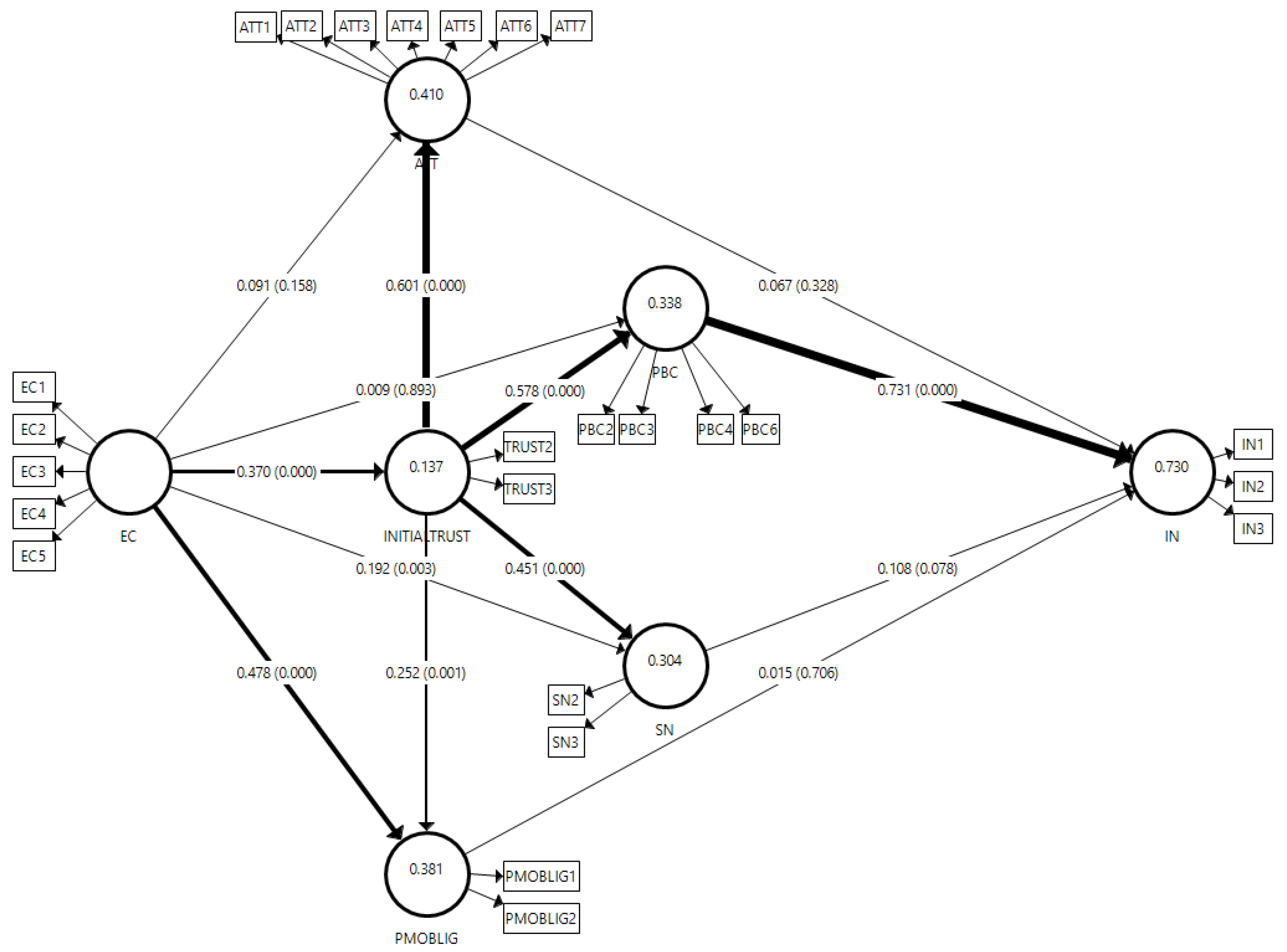

Finally, looking at the structural model, multicollinearity was evaluated by considering the value of the variance inflation factor (VIF). The obtained VIFs for both models were significantly below 5.0, indicating that no issues existedexist concerning collinearity among the predictor variables [55]. Path coefficients and their significance are summarized in Table 2. A visual representation of the results, which also includes the R2 values, can be found in the Appendix A (see Figure A1 for the Share Now group and Figure A2 for the Stadtmobil group).

Table 2.

Path coefficients and significance for the Share Now group and Stadtmobil group.

4. Results

The results shown in Table 2 reveal some initial interesting differences, e.g., when looking at the effect of the antecedent environmental concern. Although environmental concern has a medium to strong impact on initial trust, perceived moral obligations, and social norms in the Stadtmobil model, the environmental construct only affects the perceived moral obligation in the Share Now model. Initial trust has a medium effect on perceived moral obligations in the Stadtmobil model, whereas this effect was not able to be detected in the Share Now model. Medium to high correlations between initial trust and attitude, perceived behavioral control, and social norms wereare found. These correlations tend to be slightly higher in the Stadtmobil model compared to the Share Now model. In addition, the direct effect of perceived behavioral control on usage intention of carsharing appears to be more pronounced for the Stadtmobil service. An interesting aspect is that, at least when estimating the models separately, the opposite effect between the constructs of attitude and usage intention was found. People with a positive attitude toward the business model tend to have a higher willingness to use the free-floating service of Share Now. This effect was not able to be revealed for the station-based carsharing offerings of Stadtmobil.

An unresolved question is whether these differences, which can be observed for the path coefficients when estimating the models separately, are statistically significant. To answer this question (RQ1), we examined the results of the MGA, which enables a comparison of the group-specific outcomes. These results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Absolute difference between path coefficients and significance for the Share Now group and Stadtmobil group.

There is a significant difference for the attitude and intention to use relationship. The positive sign indicates that the path coefficient in the Share Now group is significantly larger than in the Stadtmobil group. Another significant difference refers to the relationship between initial trust and attitude. As shown in Table 2, the path coefficients in the Stadtmobil group are larger than the path coefficients in the Share Now group. The third significant difference relates to the effect between perceived behavioral control and intention to use. Due to the negative sign, it is obvious that the path coefficient in the Share Now group is significantly smaller than that in the Stadtmobil group.

Finally, Table 4 addresses the second research question and provides an overview of the total effects of each individual construct on usage intention, which was specified as the target outcome construct.

Table 4.

Absolute difference between total effects and significance for the Share Now group and Stadtmobil group.

Considering the two hypotheses, we concluded that there was no significant difference in the total effects of initial trust on usage intention, or of environmental concern on usage intention. However, when looking at the signs of the absolute differences between the total effects, it was clearly shown that the total effect of both constructs in the Share Now group tended to be less pronounced. Despite the lack of significance, the general line of argument appeared to be supported.

5. Discussion

The aim of this empirical study was to examine whether there are differences in the factors influencing the usage intention of free-floating carsharing in comparison to station-based carsharing, with a particular focus on the effect of environmental concern and initial trust. For this purpose, two standardized online surveys were conducted among consumers within Germany, referring either to Share Now, the biggest free-floating operator in Germany, or to Stadtmobil, the biggest station-based operator in Germany. The final data set contained 262 observations (nShare Now = 98, nStadtmobil = 164). The results showed a significantly stronger correlation between the attitude towards the carsharing business model and the usage intention of free-floating compared to station-based services. It was shown that the effect of perceived behavioral control on usage intention was significantly smaller for the Share Now consumers. Although not significant, results appear to indicate slightly higher total effects of environmental concern and initial trust on the usage intention of station-based compared to free-floating carsharing.

The research clearly showed that the effects of antecedents on usage intentions for carsharing services can substantially differ depending on the related business model (see Table 3 and Table 4). This interesting difference arises, for example, for the relationship between ATT and IN. In the case of Share Now, positive attitudes thus lead to a significantly higher intention to use. For the station-based Stadtmobil sample, however, the effect is minimal and not significant. One reason for this could be that the construct addresses aspects such as enjoyment or pleasantness. These appear to be issues that are fundamentally more strongly addressed by free-floating carsharing. The business model interacts in a more “modern” way, for example, due to the general significance of the use of mobile phones or specific gadgets, and the integration of human–machine interface approaches. Station-based carsharing, by comparison, focuses on the primary use of a vehicle, and interactions with the customer are more traditional.

Interestingly, the relationship between PBC and IN showed an initially unexpected result. A more pronounced effect was seen in the case of station-based carsharing. Due to the respective utilization structures, however, the PBC would be expected to be higher in the case of free-floating carsharing. Objectively, this concept is comparatively simpler. An app is the central mediator for all relevant aspects, such as booking options, access to the vehicle, or payment functions. Station-based carsharing structures are usually more complicated. For example, traditional key boxes are the only means of access to the vehicle. One possible explanation for this result could be that, due to the strong similarity to other everyday offers, access to free-floating carsharing is generally less questioned. Accordingly, controllability and usability of the concept may play a subordinate role and are therefore not questioned in detail by (potential) users.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

The findings provide valuable insights for future theoretical developments. Many research statements regarding variables that determine usage intentions have been made for carsharing in general, without respect to the individual specifics of a business model. These distinguishing criteria could be used to describe the segment users in more detail. Contributions therefore could serve as a direction for future context-related research on carsharing acceptance and adoption within a certain business model context. In the current study, the models explained different amount of variance regarding the target constructs at Stadtmobil and Share Now. This suggests greater potential for business model-related development of constructs that could explain the acceptance and usage intentions of a specific carsharing service. This could be even more relevant in regard to other mobility services, such as shared e-scooters, or the future usage potential of services, such as automated ridesharing or robotaxis.

In line with existing research [27,29,30,31], however, the available data also show that the initial trust factor is a significant influencing variable with regard to the acceptance and intentions to use mobility concepts. This applies equally to the free-floating and station-based concepts. Offering a reliable and trustworthy product is therefore of particular importance to be able to attract customer groups to a particular range of products. In the mobility sector, safety aspects appear to be particularly relevant in this respect; for example, vehicle fleets should meet the highest safety standards.

Although the calculation of the absolute differences between the total effects did not show significance, it is nevertheless clear that the total effect of both the EC and INITIALTRUST constructs tends to be less pronounced in the Share Now group. This tendency corresponds well with existing research results. These results show that environmental awareness is more important in the case of station-based carsharing users [63]. The more noticeable tendency of the trust factor in the case of the Stadtmobil group could be based on the fact that users of traditional carsharing are more convinced about the idea of the concept rather than its individual advantages, such as spontaneous car trips instead of using public transport, for example. The fundamental trustworthiness of a concept, therefore, appears to be an important prerequisite for traditional carsharing customers.

6.2. Managerial Implications

Based on these findings, valuable insights for managers of carsharing operators can be provided. The results clearly showed that environmental concern and trust tend to have greater effects on usage intention for station-based carsharing; thus, these providers could focus on addressing the sustainability effects of carsharing, and develop their offerings and communication strategies around sustainability and a circular economy business model [64]. A strong focus on electromobility vehicle fleets also appears to be promising. By following this approach, the issue of environmental awareness would be directly visible to (potential) customers. Particularly as a result of the controversial debate in Germany about driving restrictions in inner-city areas, carsharing providers can make a clear statement. It is also conceivable, on a transitional basis, to grant customers certain advantages if an electric vehicle from the fleet is used instead of the conventional car. In addition, emphasizing the trustworthiness of their services may have a positive effect on their business success. As the attitude towards the respective carsharing business model had a greater effect on the usage intentions of free-floating services, operators should identify opportunities to strengthen the related factors. The construct contained the factors of pleasantness and enjoyment. By providing technically sophisticatedsophistic solutions with significant effects on enjoyment and entertainment (e.g., excellent booking apps or car human–machine interfaces using a gamification approach), providers of free-floating options, in particular, could achieve positive effects on usage intentions of their services and their businesses.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

The present study was an important first attempt to examine the possible factors that determine the usage intentions of free-floating carsharing compared to station-based carsharing. The consideration of these mobility services as two different carsharing options is one of the main strengths of this study compared to the existing literature. Nevertheless, the current study has some limitations, which also provide starting points for further research, as follows.

An approach for future research could be the optimization of the sample with regard to group size. Group sizes in the current study were slightly unbalanced, which might affect the results of the MGA, and thus the statistical differences between the two carsharing groups. Further data collection for the Share Now concept would, therefore, appear to be necessary.

The underlying theoretical model [48] aims to examine the intentions of users. Although this approach is not unusual in research, it should be considered that an intention cannot necessarily be equated to an actual behavior. The origin model for ToPB [65] therefore considers the actual behavior of persons as a target variable. Future studies should also address this aspect. In this context, the implementation of real user experience appears to be promising. Although the available database includes actual carsharing users, it also includes people who only have knowledge of the concepts but no practical experience. A standardized approach to test persons with experience of both station-based and free-floating carsharing can thus further increase the quality of the data in this context. Although environmental concern was found to have an influence on the topic of interest, this influence was less pronounced than expected based on theory. One reason for this could be the global level of operationalization. It can be assumed that this influencing factor could be improved with the use of a more mobility-related operationalization. The current study focused on classical influencing factors of ToPB, and was particularly interested in the constructs of environmental concern and trust, which are considered to be highly significant in the existing literature. Nevertheless, it should be recalled that other influencing factors are also discussed in the literature (e.g., sociodemographic factors or car ownership). However, these were not considered in the present case. In addition, it must be noted that the study design was only implemented in Germany. It is possible that different effects may emerge in other country contexts. This is particularly conceivable for countries in which carsharing is used comparatively more or less intensively. Thus, to generate more reliable results, the study design should also be applied to other country contexts.

Furthermore, a more in-depth analysis of concrete interventions with regard to the factors of environmental concern and trust appears to be relevant. For example, what is the influence of the special security concepts of mobility providers? What is the effect of the predominant use of electric vehicles in the respective fleets? Therefore, the consideration of qualitative methods, in addition to a quantitative approach to data collection, also appears to be a worthy research topic. A stronger qualitative focus may be helpful to better understand certain dependencies. However, for large samples, a qualitative approach may also be problematic in terms of data handling and, in particular, evaluation. Thus, a qualitative analysis of a single sub-sample is probably appropriate to obtain a better understanding of this context.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K.; methodology, V.M.; software, V.M.; validation, M.K.; formal analysis, M.K., V.M. and S.S.; investigation, M.K. and S.S.; resources, M.K.; data curation, V.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K. and V.M.; writing—review and editing, M.K., V.M. and S.S.; visualization, V.M.; supervision, M.K.; project administration, M.K.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Baden-Wuerttemberg Cooperative State University Stuttgart (25 June 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in https://nextcloud.dhbw-stuttgart.de/index.php/s/5et6dT2Md3FQrXT (accessed on 1 May 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Criteria for assessing convergent validity and reliability.

Table A1.

Criteria for assessing convergent validity and reliability.

| Share Now | Stadtmobil | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | Items | Outer Loadings | AVE | Cronbach’s α | Dijkstra–Henseler’s ρA | Composite Reliability ρC | Outer Loadings | AVE | Cronbach’s α | Dijkstra–Henseler’s ρA | Composite Reliability ρC |

| Attitude | ATT1 | 0.847 | 0.682 | 0.922 | 0.929 | 0.937 | 0.807 | 0.692 | 0.925 | 0.926 | 0.940 |

| ATT2 | 0.785 | 0.815 | |||||||||

| ATT3 | 0.823 | 0.851 | |||||||||

| ATT4 | 0.852 | 0.810 | |||||||||

| ATT5 | 0.727 | 0.795 | |||||||||

| ATT6 | 0.851 | 0.860 | |||||||||

| ATT7 | 0.886 | 0.880 | |||||||||

| Environmental Concern | EC1 | 0.873 | 0.714 | 0.900 | 0.909 | 0.926 | 0.819 | 0.655 | 0.868 | 0.872 | 0.904 |

| EC2 | 0.854 | 0.773 | |||||||||

| EC3 | 0.770 | 0.807 | |||||||||

| EC4 | 0.882 | 0.791 | |||||||||

| EC5 | 0.840 | 0.853 | |||||||||

| Intention (to use) | IN1 | 0.875 | 0.835 | 0.900 | 0.900 | 0.938 | 0.926 | 0.880 | 0.932 | 0.934 | 0.957 |

| IN2 | 0.929 | 0.937 | |||||||||

| IN3 | 0.935 | 0.952 | |||||||||

| Initial Trust | TRUST2 | 0.937 | 0.901 | 0.891 | 0.926 | 0.948 | 0.953 | 0.917 | 0.909 | 0.916 | 0.957 |

| TRUST3 | 0.961 | 0.962 | |||||||||

| Perceived Behavioral Control | PBC2 | 0.859 | 0.737 | 0.882 | 0.894 | 0.918 | 0.880 | 0.726 | 0.874 | 0.885 | 0.914 |

| PBC3 | 0.903 | 0.851 | |||||||||

| PBC4 | 0.860 | 0.886 | |||||||||

| PBC6 | 0.810 | 0.789 | |||||||||

| Perceived Moral Obligation | PMOBLIG1 | 0.913 | 0.853 | 0.829 | 0.840 | 0.921 | 0.865 | 0.802 | 0.757 | 0.797 | 0.890 |

| PMOBLIG2 | 0.934 | 0.925 | |||||||||

| Subjective Norms | SN2 | 0.910 | 0.856 | 0.834 | 0.857 | 0.923 | 0.885 | 0.813 | 0.771 | 0.785 | 0.897 |

| SN3 | 0.940 | 0.918 | |||||||||

Note: Outer loadings and AVE refer to convergent validity. Cronbach’s α, Dijkstra–Henseler’s ρA and Composite Reliability ρC refer to reliability.

Table A2.

Fornell–Larcker criterion for assessing discriminant validity.

Table A2.

Fornell–Larcker criterion for assessing discriminant validity.

| Share Now | Stadtmobil | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | EC | IN | INITIAL TRUST | PBC | PMOBLIG | SN | ATT | EC | IN | INITIAL TRUST | PBC | PMOBLIG | SN | |

| ATT | 0.826 | 0.832 | ||||||||||||

| EC | 0.194 | 0.845 | 0.314 | 0.809 | ||||||||||

| IN | 0.697 | 0.175 | 0.914 | 0.689 | 0.241 | 0.938 | ||||||||

| INITIAL TRUST | 0.438 | 0.168 | 0.426 | 0.949 | 0.635 | 0.370 | 0.579 | 0.957 | ||||||

| PBC | 0.622 | 0.172 | 0.774 | 0.462 | 0.859 | 0.756 | 0.223 | 0.847 | 0.582 | 0.852 | ||||

| PMOBLIG | 0.149 | 0.625 | 0.201 | 0.195 | 0.144 | 0.924 | 0.261 | 0.571 | 0.253 | 0.428 | 0.258 | 0.895 | ||

| SN | 0.506 | 0.033 | 0.531 | 0.306 | 0.534 | −0.014 | 0.925 | 0.610 | 0.358 | 0.570 | 0.522 | 0.570 | 0.300 | 0.902 |

Note: Diagonal elements in bold represent the square roots of the shared variance between the constructs and their indicators (AVE); off-diagonal elements represent the correlations among the constructs (interconstruct correlation).

Table A3.

HTMT values and 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals for assessing discriminant validity for the Share Now group.

Table A3.

HTMT values and 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals for assessing discriminant validity for the Share Now group.

| Share Now | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | EC | IN | INITALTRUST | PBC | PMOBLIG | |

| ATT | ||||||

| EC | 0.214 | |||||

| [0.098; 0.472] | ||||||

| IN | 0.756 | 0.196 | ||||

| [0.649; 0.854] | [0.091; 0.420] | |||||

| INITIATRUST | 0.467 | 0.181 | 0.470 | |||

| [0.306; 0.606] | [0.066; 0.401] | [0.308; 0.603] | ||||

| PBC | 0.681 | 0.187 | 0.857 | 0.508 | ||

| [0.551; 0.798] | [0.090; 0.422] | [0.757; 0.941] | [0.348; 0.650] | |||

| PMOBLIG | 0.166 | 0.714 | 0.234 | 0.220 | 0.172 | |

| [0.078; 0.415] | [0.511; 0.865] | [0.100; 0.417] | [0.053; 0.431] | [0.089; 0.371] | ||

| SN | 0.564 | 0.104 | 0.609 | 0.344 | 0.620 | 0.076 |

| [0.366; 0.741] | [0.076; 0.308] | [0.414; 0.789] | [0.137; 0.555] | [0.439; 0.787] | [0.042; 0.334] |

Note: 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals are reported in parentheses. Confidence intervals based on 5000 bootstrap subsamples.

Table A4.

HTMT values and 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals for assessing discriminant validity for the Stadtmobil group.

Table A4.

HTMT values and 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals for assessing discriminant validity for the Stadtmobil group.

| KERRYPNX | Stadtmobill | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | EC | IN | INITALTRUST | PBC | PMOBLIG | |

| ATT | ||||||

| EC | 0.342 | |||||

| [0.184; 0.503] | ||||||

| IN | 0.742 | 0.258 | ||||

| [0.648; 0.820] | [0.141; 0.402] | |||||

| INITIATRUST | 0.690 | 0.409 | 0.628 | |||

| [0.589; 0.773] | [0.204; 0.608] | [0.533; 0.713] | ||||

| PBC | 0.839 | 0.242 | 0.929 | 0.645 | ||

| [0.757; 0.906] | [0.156; 0.403] | [0.874; 0.975] | [0.545; 0.738] | |||

| PMOBLIG | 0.307 | 0.687 | 0.307 | 0.511 | 0.313 | |

| [0.127; 0.481] | [0.489; 0.876] | [0.133; 0.462] | [0.268; 0.703] | [0.134; 0.478] | ||

| SN | 0.720 | 0.425 | 0.671 | 0.614 | 0.684 | 0.391 |

| [0.598; 0.830] | [0.275; 0.566] | [0.528; 0.798] | [0.489; 0.723] | [0.537; 0.813] | [0.226; 0.552] |

Note: 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals are reported in parentheses. Confidence intervals based on 5000 bootstrap subsamples.

Figure A1.

Structural equation model for the Share Now group. Note: Highlighted are the absolute values. Within each construct, R2 values are reported.

Figure A1.

Structural equation model for the Share Now group. Note: Highlighted are the absolute values. Within each construct, R2 values are reported.

Figure A2.

Structural model for the Stadtmobil group. Note: Highlighted are the absolute values. Within each construct, R2 values are reported.

Figure A2.

Structural model for the Stadtmobil group. Note: Highlighted are the absolute values. Within each construct, R2 values are reported.

References

- Liang, X.; Li, J.; Xu, Z. The Impact of Perceived Risk on Customers’ Intention to Use--An Empirical Analysis of DiDi Car-Sharing Services. In Proceedings of the ICEB 2018 Proceedings, Guilin, China, 6 December 2018; Volume 34. [Google Scholar]

- Hamari, J.; Sjöklint, M.; Ukkonen, A. The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balck, B.; Cracau, D. Empirical Analysis of Customer Motives in the Shareconomy: A Cross-Sectoral Comparison; OVGU: Magdeburg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawlitschek, F.; Teubner, T.; Gimpel, H. Understanding the Sharing Economy—Drivers and Impediments for Participation in Peer-to-Peer Rental. In Proceedings of the 2016 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Koloa, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 4782–4791. [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen, S.; Chan, N. Mobility and the Sharing Economy: Potential to Facilitate the First- and Last-Mile Public Transit Connections. Built Environ. 2016, 42, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghard, U.; Dütschke, E. Who wants shared mobility? Lessons from early adopters and mainstream drivers on electric carsharing in Germany. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2019, 71, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprei, F. Disrupting mobility. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 37, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- movmi. Carsharing Market & Growth Analysis. 2019. Available online: https://movmi.net/carsharing-market-growth-2019/ (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Bundesverband Carsharing. Carsharing Statistics 2019. Available online: https://www.carsharing.de/presse/pressemitteilungen/carsharing-statistic-2019-carsharing-germany-is-still-on-a-growing-path (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Fellows, N.; Pitfield, D. An economic and operational evaluation of urban car-sharing. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2000, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielinski, G.; Trépanier, M.; Morency, C. What about Free-Floating Carsharing? Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2016, 2563, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clewlow, R.; Mishra, G.S. Disruptive Transportation: The Adoption, Utilization, and Impacts of Ride-Hailing in the United States; ITS Research Report 2017; ITS: Davis, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jorge, D.; Correia, G. Carsharing systems demand estimation and defined operations: A literature review. European Journal of Transport and Infrastructure Research 2013. Eur. J. Transp. Infrastruct. Res. 2013, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefers, T. Exploring carsharing usage motives: A hierarchical means-end chain analysis. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pr. 2013, 47, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firnkorn, J.; Müller, M. What will be the environmental effects of new free-floating car-sharing systems? The case of car2go in Ulm. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 1519–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, H.; Ciari, F.; Axhausen, K.W. Comparing car-sharing schemes in Switzerland: User groups and usage patterns. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pr. 2017, 97, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Witzke, S. Carsharing und die Gesellschaft von Morgen; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kawgan-Kagan, I. Early adopters of carsharing with and without BEVs with respect to gender preferences. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2015, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lavieri, P.S.; Garikapati, V.M.; Bhat, C.R.; Pendyala, R.M.; Astroza, S.; Dias, F.F. Modeling Individual Preferences for Ownership and Sharing of Autonomous Vehicle Technologies. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2017, 2665, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paundra, J.; Rook, L.; van Dalen, J.; Ketter, W. Preferences for car sharing services: Effects of instrumental attributes and psychological ownership. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 53, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greenblatt, J.B.; Shaheen, S. Automated Vehicles, On-Demand Mobility, and Environmental Impacts. Curr. Sustain. Energy Rep. 2015, 2, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burkhardt, J.E.; Millard-Ball, A. Who is Attracted to Carsharing? Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2006, 1986, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costain, C.; Ardron, C.; Habib, K.N. Synopsis of users’ behaviour of a carsharing program: A case study in Toronto. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pr. 2012, 46, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury, S.; Tom, A.; Jamet, E.; Colas-Maheux, E. What drives corporate carsharing acceptance? A French case study. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2017, 45, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbourne, W.; Pickett, G. How materialism affects environmental beliefs, concern, and environmentally responsible behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransson, N.; Gärling, T. Environmental Concern: Conceptual Definitions, Measurement Methods, and Research Findings. J. Environ. Psychol. 1999, 19, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.; Rampersad, G. Trust in driverless cars: Investigating key factors influencing the adoption of driverless cars. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2018, 48, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wua, K.; Zhaoa, Y.; Zhua, Q.; Tana, X.; Zhengb, H. A meta-analysis of the impact of trust on technology acceptance model: Investigation of moderating influence of subject and context type. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2011, 31, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Tao, D.; Qu, X.; Zhang, X.; Lin, R.; Zhang, W. The roles of initial trust and perceived risk in public’s acceptance of automated vehicles. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 98, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, L.; Bélanger, F. The utilization of e-government services: Citizen trust, innovation and acceptance factors. Inf. Syst. J. 2005, 15, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Jing, J.; Guo, H. The Role of Trust with Car-Sharing Services in the Sharing Economy in China: From the Consumers’ Perspective. In Transactions on Petri Nets and Other Models of Concurrency XV; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 10281, pp. 634–646. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Yang, Y. The Role of Trust towards the Adoption of Mobile Services in China: An Empirical Study. In Security Education and Critical Infrastructures; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 445, pp. 46–57. [Google Scholar]

- Schmöller, S.; Weikl, S.; Müller, J.; Bogenberger, K. Empirical analysis of free-floating carsharing usage: The Munich and Berlin case. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2015, 56, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoepf, S.M.; Keith, D.R. User decision-making and technology choices in the U.S. carsharing market. Transp. Policy 2016, 51, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, F.; Perboli, G.; Rosano, M.; Vesco, A. Car-sharing services: An annotated review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 37, 501–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, T.; Cherry, C.R.; Jones, L.R. One-way and round-trip carsharing: A stated preference experiment in Beijing. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2017, 53, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Namazu, M.; Dowlatabadi, H. Vehicle ownership reduction: A comparison of one-way and two-way carsharing systems. Transp. Policy 2018, 64, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efthymiou, D.; Antoniou, C.; Waddell, P. Factors affecting the adoption of vehicle sharing systems by young drivers. Transp. Policy 2013, 29, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yan, X.; Zhou, Y.; Xue, Q.; Sun, L. Individuals’ Acceptance to Free-Floating Electric Carsharing Mode: A Web-Based Survey in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Müller, J.M. Comparing Technology Acceptance for Autonomous Vehicles, Battery Electric Vehicles, and Car Sharing—A Study across Europe, China, and North America. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Wei, J.; Wang, C. An empirical study of consumers’ intention to use ride-sharing services: Using an extended technology acceptance model. Transportation 2020, 47, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, M.; Raats, M.M.; Shepherd, R. The Role of Self-Identity, Past Behavior, and Their Interaction in Predicting Intention to Purchase Fresh and Processed Organic Food1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 42, 669–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, A.; Peng, N. Green hotel knowledge and tourists’ staying behavior. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 2211–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.; Manca, F.; Nielsen, T.A.S.; Prato, C.G. Intentions to use bike-sharing for holiday cycling: An application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, P.; Goel, P. Willingness to use carsharing apps: An integrated TPB and TAM. Int. J. Indian Cult. Bus. Manag. 2019, 19, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Park, H.J. Factors affecting the Usage Intention of Car-Sharing Service. J. Digit. Converg. 2019, 17, 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.-F.; Tung, P.-J. Developing an extended Theory of Planned Behavior model to predict consumers’ intention to visit green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglbauer, K. Vertrauen als Input-/Output-Variable in elektronischen Verhandlungen; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Borhan, M.N.; Ibrahim, A.N.H.; Miskeen, M.A.A. Extending the theory of planned behaviour to predict the intention to take the new high-speed rail for intercity travel in Libya: Assessment of the influence of novelty seeking, trust and external influence. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pr. 2019, 130, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.N.H.; Borhan, M.N.; Rahmat, R.A.O. Understanding Users’ Intention to Use Park-and-Ride Facilities in Malaysia: The Role of Trust as a Novel Construct in the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.-T.; Sheu, C. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.-P. Predicting Intentions to Conserve Water From the Theory of Planned Behavior, Perceived Moral Obligation, and Perceived Water Right1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 29, 1058–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSA—Car Sharing Association. Available online: https://carsharing.org/ (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Hair, J.F.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, Seventh Edition, Pearson New International Edition; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Urban, D.; Mayerl, J.; Wahl, A. Regressionsanalyse bei Fehlenden Variablenwerten (Missing Values): Imputation Oder Nicht-Imputation? Eine Anleitung für die Regressionspraxis mit SPSS; Schriftenreihe des Instituts für Sozialwissenschaften der Universität Stuttgart: Stuttgart, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, P.E.; McKnight, K.M.; Sidani, S.; Figueredo, A.J. Missing Data: A Gentle Introduction; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kowarik, A.; Templ, M. Imputation with the R Package VIM. J. Stat. Softw. 2016, 74, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jonsson, P.; Wohlin, C. An evaluation of k-nearest neighbour imputation using likert data. In Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on Software Metrics, Chicago, IL, USA, 11 September 2004; pp. 108–118. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 3; SmartPLS. Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Richter, N.F.; Hauff, S. Partial Least Squares Strukturgleichungsmodellierung: Eine anwendungsorientierte Einführung; Franz Vahlen: München, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit. Wirkung von E-Car Sharing Systemen auf Mobilität und Umwelt in urbanen Räumen (WiMobil). Available online: https://www.erneuerbar-mobil.de/sites/default/files/2016-10/Abschlussbericht_WiMobil.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Bressanelli, G.; Adrodegari, F.; Perona, M.; Saccani, N. Exploring How Usage-Focused Business Models Enable Circular Economy through Digital Technologies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).