The Role of Community-Led Food Retailers in Enabling Urban Resilience

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Urban Retailing and Community-Led Food Retailers (CLFRs)

2.2. The CLFR through a Spatial and Relational Resilience Lens

2.2.1. Understanding Urban Resilience

2.2.2. Understanding Community Resilience

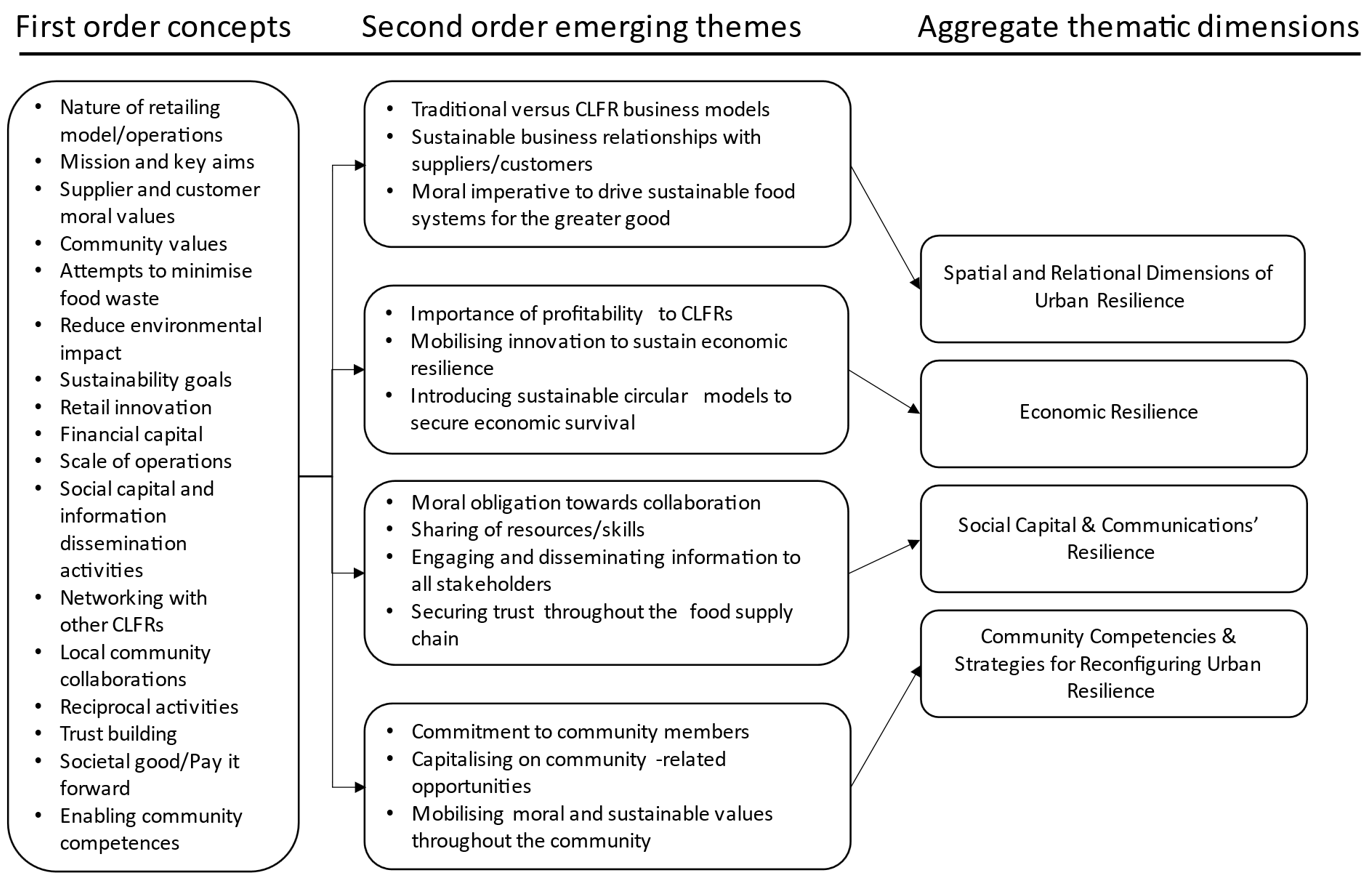

3. Research Methodology

4. Findings and Discussion

4.1. Spatial and Relational Dimensions of Urban Resilience

“We have always operated in complete contrast to the contemptible supermarket-led supply chains that promote the ritual disposal of colossal amounts of perfectly edible food”(CLFR—Greater Manchester).

“The only sustainable model for retailing food for the future is social enterprise because it can’t just be about short-term profit…We’ve seen that model doesn’t work. Pile it high and sell it cheap since the 60 s, and now look at obesity and food related diseases and how many zillion kids with ADHD that can’t concentrate at school, because they are not eating the right food. And it’s all down to supermarkets…they just pass the knock-on costs and impact to externalise the cost of doing our business in everything”(CLFR—Brighton).

“We have the 1%, 4% fund. With the 4%—accepting that we are part of a global trading system and much of the harm is in the global south, we fund projects for groups…kind of securing their future with their community with skills or energy or their food experience. The 1% is for community activities and they can be for various things”(CLFR 2—Manchester).

“Because we are fairly new, our immediate objective is to stay in business and treat our staff well to serve the community with what we’ve offered to the people who have bought it. I think the ideal would be to grow and develop and still be here in ten years’ time…But also to be doing more for the community who invested in the first place”(CLFR—Greater Manchester).

4.2. Economic Resilience

“[Our] buying power isn’t as big as theirs [the retail multiples]…but we have a special relationship with other co-operatives, so our organic eggs are much cheaper than [major UK food retailer]; and our wall of beans when you come in the shop, beat any [major UK food retailer] hands down, because it’s all organic”(CLFR1—Manchester).

“It’s a 100 per cent intercepted food…If people have got no money and they walk in, they’ll get fed…it’s ended up getting a lot of press, which is great...sometimes we can get between £5 and £10 a head depending on who your customers are”(CLFR 2—Edinburgh).

“What gives me confidence and strength, is knowing that these initiatives are coming from small start-ups, social enterprises that have been started with values, decency at the core of their model. Trying to do what’s right, rather than trying to profit maximise and that for me represents quite an exciting shift in business…So that probably is a big difference in the kind of social enterprise sector compared to traditional capitalist systems”(CLFR 3—Manchester).

4.3. Social Capital, Communications and Resilience

“We’ve done school scenarios where I’ve gone to talk to a collection of parents; six/seven is the ideal age. It’s a ten-week project, they have to go and research food waste. They have to go and find their own suppliers…I get them to negotiate with the kitchen and then the day before the dinner’s due I go and see what they’ve collected, and I bring what else is needed to make it into nice food. Then I knock it up…I’ve loved the school events”(CLFR 2—Edinburgh).

“In September 2010, the store acquired a complete ex-demonstration domestic kitchen…Our members are gaining life skills through direct hands-on working in the kitchen, including food hygiene training, cookery lessons and teamwork”(CLFR—London).

“Legally speaking there’s just myself, but I estimate there’s about maybe fifteen people in various different capacities working on the project and I’ve had some great support as well from the School for Social Entrepreneurs who back social enterprises up and down the UK”(CLFR 3—Manchester).

“We owe a lot to other co-operators who have helped to set us up, which is one of the great things about the Co-op movement, really. We are really unique in that we’ve cornered this collective kind of governance of our business…We are trying to spend this year looking at ways that we can keep this kind of structure with that engagement and keep it dynamic and get the new members to feel as closely; as much ownership of people who have been there longer”(CLFR 2—Manchester).

“We try and choose our suppliers quite carefully. So, we use a local supplier for the flour and one from the Cotswolds… We don’t have any contracts with any of our suppliers. We set up regular orders with them and so they know that they are likely to get orders from us every week or every fortnight, but they have no guarantee that we are going to order… It’s all done on trust”(CLFR—Birmingham).

“One of the reasons we like to work with a national food distribution network is that they by and large are now supporting projects whereby we also cook for people. It’s less of an older style handout system whereby someone would just turn up and receive maybe ten different items. The food goes to a community project or groups, say, for example, a rehabilitation centre where a meal is cooked, and people go along, and they eat and it’s the added benefit of having social interaction as well as getting a meal”(CLFR 3—Manchester).

4.4. Community Competences and Strategies for Reconfiguring Urban Resilience

“I get people sticking out their tongues and showing me their rashes and things like that… It’s a big part of the business…there’s myself and another clinical nutritionist—people get a service here that they would get really in a clinic. People regularly bring me in their blood results…or ask me whether to go and test it with a GP. Not everybody can afford to go and see a nutritionist”(CLFR 1—Manchester).

“The shop closes at 3 pm and we do our cashing up and stuff and then the homeless kind of queue up outside. Everything that’s left over gets distributed fairly between all the homeless people, so nothing goes to waste from the shops. Then from four o’clock on a Monday we do our Social Suppers so that’s when most of them come in. They can sit, they can have dinner. We have Big Issue, Shelter Scotland support workers here who are willing to help and offer any advice. We also partner up with Shelter Scotland as well so that if a homeless person was to come in and speak to us about being homeless, we can pass the details of all the other organisations where they can go to”(CLFR—Glasgow).

“If somebody from outside our area wanted bread and they wanted it delivered and stuff we’d just say, no. There is other businesses in the area that can do that…I personally like the fact that we know who is eating our bread and have got a relationship with our customers that come in. We know their children and their dogs and all the rest of it. It’s a proper community kind of shop…We are not set up to supply restaurants and cafes and stuff. We could do, there is a lot of money to be made potentially doing that, but that’s not us”(CLFR—Birmingham).

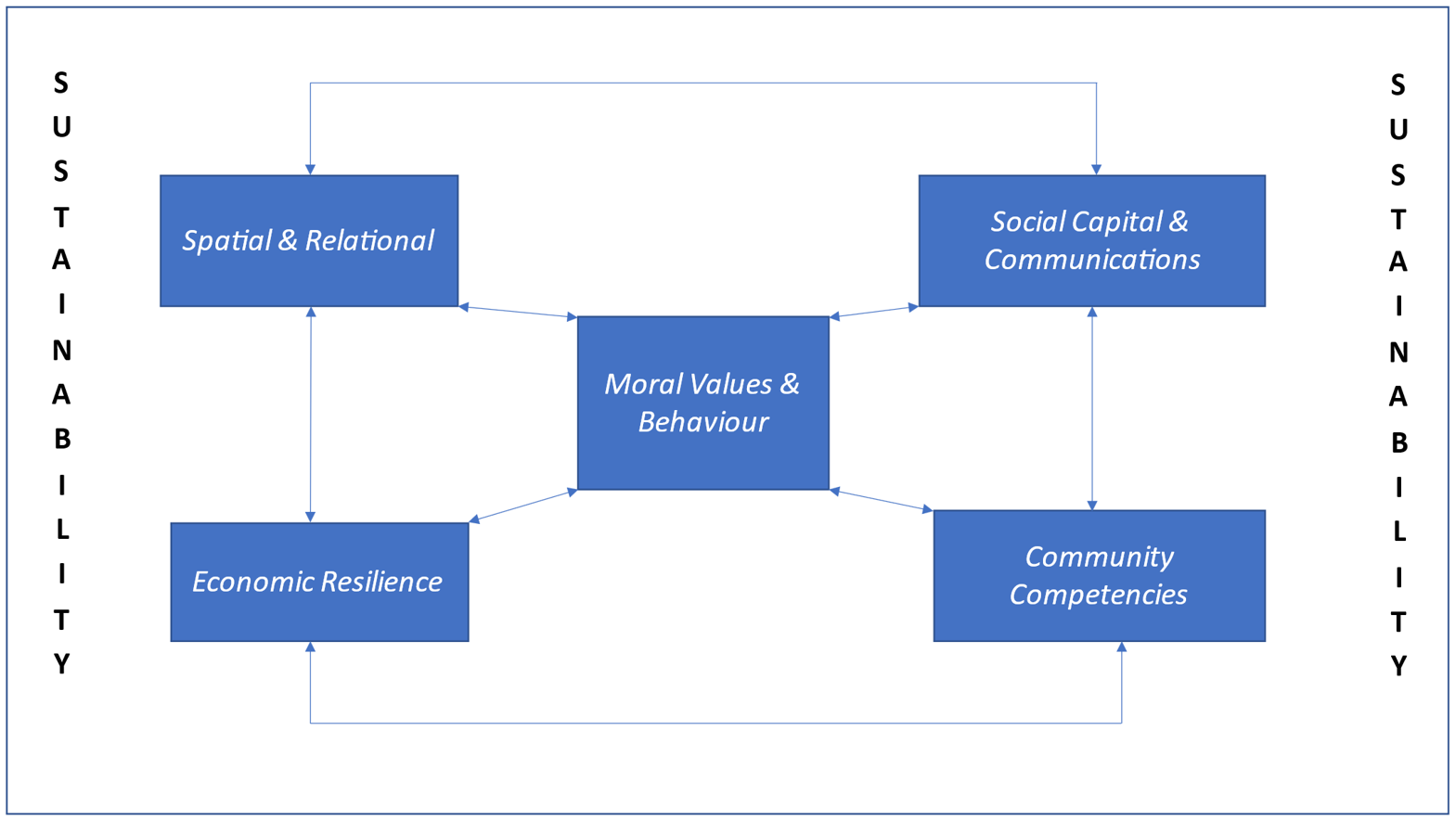

5. Conclusions, Recommendations and Avenues for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Norris, F.H.; Stevens, S.P.; Pfefferbaum, B.; Wyche, K.F.; Pfefferbaum, R.L. Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata-Salgueiro, T.; Guimarães, P. Public Policy for Sustainability and Retail Resilience in Lisbon City Center. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, L. Towns, High Streets and Resilience in Scotland: A question for policy? Sustainability 2021, 13, 5631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, M.L.; Esper, T.; Morris, M. Exploring the impact of supply chain counterproductive work behaviours on supply chain relationships. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2013, 43, 786–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, V.; Ulusoy, E.; Batat, W. New paths in researching “alternative” consumption and well-being in marketing: Alternative food consumption/Alternative food consumption: What is “alternative”?/Rethinking “literacy” in the adoption of AFC/Social class dynamics in AFC. Mark. Theory 2016, 16, 561. [Google Scholar]

- Chkanikova, O.; Mont, O. Overview of Sustainability Initiatives in European Food Retail Sector; Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, P.C.; Batat, W.; Ulusoy, E. Rethinking ‘literacy’ in the adoption of AFC. Mark. Theory 2016, 16, 565–568. [Google Scholar]

- WRAP. Quantification of Food Surplus, Waste and Related Materials in the Grocery Supply Chain; WRAP: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, G.E.; Page, M.A. Sustainability initiatives: A competing values framework. Compet. Forum 2012, 10, 176. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P.; Comfort, D.; Hillier, D. Moving towards sustainable food retailing”? Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2008, 36, 995–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderwood, E.; Davies, K. The trading profiles of community retail enterprises. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2012, 40, 592–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Hillier, D.; Comfort, D. In the public eye: Sustainability and the UK’s leading retailers. J. Public Aff. 2013, 13, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J.; Findlay, A. Sparks, L. The Retailing Reader; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cachinho, H. Consumerscapes and the resilience assessment of urban retail systems. Cities 2014, 36, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burt, S.L.; Sparks, L. Power and competition in the UK retail grocery market. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrigley, N.; Brookes, E. Evolving High Streets: Resilience & Reinvention: Perspectives from Social Science; ESRC/University of Southampton: Southampton, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wrigley, N.; Lambiri, D.; Astbury, G.; Dolega, L.; Hart, C.; Reeves, C.; Thurstain-Goodwin, M.; Wood, S. British High Streets: From Crisis to Recovery? A Comprehensive Review of the Evidence; ESRC/University of Southampton: Southampton, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wrigley, N.; Wood, S.; Lambiri, D. Corporate convenience store development effects in small towns: Convenience culture during economic and digital storms. Environ. Plan. A 2019, 51, 112–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holweg, C.; Lienbacher, E.; Zinn, W. Social Supermarkets—A new challenge in supply chain management and sustainability. Supply Chain Forum Int. J. 2010, 11, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BRC. A Vision for the UK Retail Industry: Delivering for Shoppers, Employers and the Economy. 2021. Available online: https://www.brc.org.uk/a-vision-for-the-UK (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- Nguyen, H.L.; Akerkar, R. Modelling, measuring, and visualising community resilience: A systematic review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEachern, M.G.; Warnaby, G. Community Building Strategies of Independent Co-operative Food Retailers. In Case Studies in Food Retailing and Distribution; Byrom, J., Medway, D., Eds.; Elsevier Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Coca-Stefaniak, A.; Hallsworth, A.G.; Parker, C.; Bainbridge, S.; Yuste, R. Decline in the British small shop independent retail sector: Exploring European parallels. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2005, 12, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megicks, P.; Warnaby, G. Market orientation and performance in small independent retailers in the UK. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 2008, 18, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, I.; Banga, S. The economic and social role of small stores: A review of UK evidence. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2011, 20, 209–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, A.; Sparks, L. The role and function of the independent small shop: The situation in Scotland. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 2000, 10, 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, E.; Weaven, S.; Dant, R. The evolution of retailing: A meta review of the literature. J. Macromarketing 2016, 36, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rahman, M.; Hussain, M. Social business, accountability, and performance reporting. Humanomics 2012, 28, 118–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peredo, A.M.; Chrisman, J.J. Toward a theory of community-based enterprise. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.; Thompson, M. Social Enterprise: Developing Sustainable Business; Palgrave-MacMillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Haugh, H. A research agenda for social entrepreneurship. Soc. Enterp. J. 2005, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, M.; Moingeon, B.; Lehmann-Ortega, L. Building social business models: Lessons from the Grameen experience. Long Range Plan 2010, 43, 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moufahim, M.; Wells, V.; Canniford, R. JMM Special Issue Call for Papers; special Issue on The Consumption, Politics and Transformation of Community. 2017. Available online: http://www.jmmnews.com/the-consumption-politics-and-transformation-of-community/ (accessed on 6 February 2017).

- Golubchikov, O. Persistent resilience. Coping with the mundane pressures of social or spatial exclusion: Introduction to a special session. In Proceedings of the RGS-IBG Annual International Conference, London, UK, 1–5 August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Aubry, C.; Kebir, L. Shortening food supply chains: A means for maintaining agriculture close to urban areas? The case of the French metropolitan area of Paris. Food Policy 2013, 41, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEachern, M.G.; Warnaby, G.; Carrigan, M.; Szmigin, I. Thinking locally, acting locally? Conscious consumers and farmers’ markets. J. Mark. Manag. 2010, 26, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coaffee, J. Towards next-generation urban resilience in planning practice: From securitization to integrated place making. Plan. Pract. Res. 2013, 28, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P.; Stults, M. Defining urban resilience: A review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 147, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumpp, E. New in town? On resilience and ‘Resilient Cities’. Cities 2013, 32, 164–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.; Barnes, L.; Berry, M.; Burton, C.; Evans, E.; Tate, E.; Webb, J. A place-based model for understanding community resilience to natural disasters. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2008, 18, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desouza, K.; Flanery, T. Designing, planning, and managing resilient cities: A conceptual framework. Cities 2013, 35, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, H.; Sheppard, E.; Webber, S.; Colven, E. Globalizing urban resilience. Urban Geogr. 2018, 39, 1276–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Star, S.L.; Griesemer, J.R. Institutional ecology ‘translations’ and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907–1939. Soc. Stud. Sci. 1989, 19, 387–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardekker, A.; Wilk, B.; Brown, V.; Uittenbroek, C.; Mees, H.; Driessen, P.; Wassen, M.; Molenaar, A.; Walda, J.; Runhaar, H. A diagnostic tool for supporting policymaking on urban resilience. Cities 2020, 101, 102691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinberger, A.; Felsenstein, D. Bouncing back or bouncing forward? Simulating urban resilience. Urban Des. Plan. 2014, 167, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.; Baker, C.N. Narratives of cultural trauma (and resilience): Collective negotiation of material wellbeing in disaster recovery. In NA-Advances in Consumer Research, 42th ed.; June, C., Stacy, W., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Duluth, MN, USA, 2014; pp. 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Azarya, V. Community. In The Social Science Encyclopaedia, 2nd ed.; Kuper, A., Kuper, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 114–115. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, S.; Conway, T.; Warnaby, G. Relationship Marketing: A Customer Experience Approach; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA; London, UK; New Delhi, India; Singapore; Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, S.M.; Hunt, D.M.; Rittenburg, T.L. Consumer vulnerability as a shared experience: Tornado recovery process in Wright, Wyoming. J. Public Policy Mark 2007, 26, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muniz, A.M.; O’Guinn, T.C. Brand community. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 27, 412–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozanne, L.; Ozanne, J.L. How alternative consumer markets can build community resiliency. Eur. J. Mark. 2016, 50, 330–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulding, C.; Kelemen, M.; Kiyomiya, T. Community based response to the Japanese tsunami: A bottom-up approach. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 268, 887–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmigin, I.T.; O’Loughlin, D.M.; McEachern, M.; Karantinou, K.; Barbosa, B.; Lamprinakos, G.; Fernández-Moya, M.E. Keep calm and carry on: European consumers and the development of persistent resilience in the face of austerity. Eur. J. Mark. 2020, 54, 1883–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longstaff, P.H. Security, Resilience, and Communication in Unpredictable Environments such as Terrorism, Natural Disasters, and Complex Technology. Program on Information Resources Policy; Harvard University, Centre for Information Policy Research: Harvard, UK, November 2005; pp. 1–103. [Google Scholar]

- De Verteuil, G.; Golubchikov, O. Can resilience be redeemed? City 2016, 20, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keitsch, M. Structuring ethical interpretations of the sustainable development goals-Concepts, implications and progress. Sustainability 2018, 10, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martin, R. Regional economic resilience, hysteresis and recessionary shocks. J. Econ. Geogr. 2012, 12, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Corley, K. The coming of age for qualitative research: Embracing the diversity of qualitative methods. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Zanhour, M.; Keshishian, T. Peculiar strengths and relational attributes of SMEs in the Context of CSR. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinecke, J.; Arnold, D.G.; Palazzo, G. Qualitative methods in business ethics, corporate responsibility, and sustainability research. Bus. Ethics Q. 2016, 26, xiii–xxii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crouch, M.; McKenzie, H. The logic of small samples in interview-based qualitative research. Social Sci. Inf. 2006, 45, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Cowley, J. The relevance of stakeholder theory and social capital theory in the context of CSR and SMEs: An Australian perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M. Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews. Forum Qual. Soz. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2010, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldana, J.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, M.G. For the lack of a boilerplate: Tips on writing up (and reviewing) qualitative research. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nova-Reyes, A.; Muñoz-Leiva, F.; Luque-Martínez, T. The tipping point in the status of socially responsible consumer behavior research? A bibliometric analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital and the organisational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, T.; Tian, Y. Social and symbolic capital and responsible entrepreneurship: An empirical investigation of SME narratives. J. Bus. Ethics. 2006, 67, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo, O.; Bell, S.J.; Mengüç, B.; Whitwell, G.J. Social capital, customer service orientation and creativity in retail stores. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 1214–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, A. Social capital, the social economy and community development. Community Dev. J. 2003, 41, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doherty, B.; Foster, G.; Mason, C.; Meehan, J.; Meehan, K.; Rotheroe, N.; Royce, M. Management for Social Enterprise; Sage: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. The Forms of Capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J., Ed.; Greenwood: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, P.S.; Kwon, S.W. Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Sinha, R.; Koradia, D.; Patel, R.; Parmar, M.; Rohit, P.; Chandan, A. Mobilizing grassroots’ technological innovations and traditional knowledge, values and institutions: Articulating social and ethical capital. Futures 2003, 35, 975–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridley-Duff, R.; Bull, M. Understanding Social Enterprise: Theory and Practice; Sage: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, A.R.; Jack, S.L. The articulation of social capital in entrepreneurial networks: A glue or a lubricant? Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2002, 14, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silkoset, R. Negative and positive effects of social capital on co-located firms’ withholding efforts. Eur. J. Mark. 2013, 47, 174–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barata-Salgueiro, T. Shops with a history and public policy. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CLFR Type | Definition |

|---|---|

| Social Supermarket | A supermarket that “receives surplus food and consumer goods from partnership companies (e.g., manufacturers, retailers) for free and will sell it at symbolic prices to a restricted group of people living in or at risk of poverty” [19] (p. 2). |

| Co-operative | An “autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically controlled enterprise” [30] (p. 12). Common types of co-operative and their definitions are given below. |

| Worker co-operatives are run by the workers, have flat structures and no hierarchy. All workers are involved in the decision-making. | |

| Consumer co-operatives exist to serve the needs of the customers, e.g., Credit Unions. | |

| Community co-operatives raise finance through community shares, and it is run for the benefit of the community. | |

| Social Enterprise | An “independent organization with social and economic objectives that aims to fulfil a social purpose as well as achieving financial stability through trading” [31] (p. 3). |

| Social Business | A business that is designed to solve a social problem. It is typically made up of a small group of members who act in a similar way to trustees [32]. |

| CIC | A Community Interest Company is a type of limited company that wants to use its profit and assets for public good. It generally has a focus on local markets services [30]. |

| Business Pseudonym | Business Model | Year of Establishment | Number of Outlets |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLFR 1—Manchester | Co-operative (Workers) | Established in 1970 | 1 |

| CLFR 2—Manchester | Co-operative (Workers) | Established in 1996 | 1 |

| CLFR 3—Manchester | Social enterprise | Established in 2014 | 1 |

| CLFR—Greater Manchester | Co-operative (Community) | Established in 2014 | 1 |

| CLFR—Lancs | CIC | Established in 2013 | 2 |

| CLFR 1—London | CIC | Established in 2010 | 1 |

| CLFR 2—London | CIC | Established in 2013 | 2 |

| CLFR—Brighton | CIC | Established in 2013 | 1 |

| CLFR—Birmingham | Co-operative (Workers) | Established in 2009 | 1 |

| CLFR—Glasgow | Social business | Established in 2011 | 5 |

| CLFR—West Yorkshire | Co-operative (Consumer) | Established in 2009 | 1 |

| CLFR—Nottingham | Independent retailer (Originally a Consumer Co-operative) | Established in 2008 | 1 |

| CLFR 1—Edinburgh | Social business | Established in 2011 | 5 |

| CLFR 2—Edinburgh | Social business | Established in 2013 | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McEachern, M.G.; Warnaby, G.; Moraes, C. The Role of Community-Led Food Retailers in Enabling Urban Resilience. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7563. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147563

McEachern MG, Warnaby G, Moraes C. The Role of Community-Led Food Retailers in Enabling Urban Resilience. Sustainability. 2021; 13(14):7563. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147563

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcEachern, Morven G., Gary Warnaby, and Caroline Moraes. 2021. "The Role of Community-Led Food Retailers in Enabling Urban Resilience" Sustainability 13, no. 14: 7563. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147563

APA StyleMcEachern, M. G., Warnaby, G., & Moraes, C. (2021). The Role of Community-Led Food Retailers in Enabling Urban Resilience. Sustainability, 13(14), 7563. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147563