Retail Policies and Urban Change in Naples City Center: Challenges to Resilience and Sustainability from a Mediterranean City

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Research Stages and Methodology

2. Theoretical Background and Conceptual Discussion

2.1. Vulnerability

2.2. Resilience

2.3. Sustainability

3. Consumption Practices, Retail Policies, and Urban Commercial Dynamics in the City Center of a Mediterranean City

3.1. Urban Retail Change in Naples City Center

3.2. Results of Empirical Research

“After 85 years in business, after two generations of trading in quality clothing, the time has unfortunately come for us to close down. We would like to thank our customers....the representatives...the companies...who have ensured the success of our business over the years, so much so that we have been awarded the regional and municipal certificate of a shop of historical interest....” [72]

“I gave new life to the old chairs from a tailor’s shop, using them as a clothes stand in the dressing rooms; […] there was a long, thick, wooden counter from a clothing shop where fabrics were unrolled and it is now where I put my merchandise; […] there was a trunk that came from a store that sold gloves, and now it is where I display my products”.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carreras, C.; D’Alessandro, L. Un repertorio bibliografico su commercio, consumo e città. In Commercio, Consumo e Città. Quaderno di Lavoro; Viganoni, L., Ed.; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2017; pp. 27–69. [Google Scholar]

- Crewe, L. Geographies of retailing and consumption: Markets in motion. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2003, 27, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mansvelt, J. Consumption Geographies: Turns or Intersections. In Encounters and Engagements between Economic and Cultural Geography; Warf, B., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; Volume 104, pp. 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crewe, L. Geographies of retailing and consumption. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2000, 24, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomley, N. I’d like to dress her all over: Masculinity, power and retail space. In Retailing, Consumption and Capital; Wrigley, N., Lowe, M., Eds.; Harlow: Longman, UK, 1996; p. 256. [Google Scholar]

- Mansvelt, J. Consumption. In International Encyclopedia of Geography: People, the Earth, Environment and Technology; Richardson, D., Castree, N., Goodchild, M.F., Kobayashi, A., Liu, W., Marston, R.A., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrigley, N.; Lowe, M. Retailing, Consumption and Capital: Towards the New Retail Geography; Harlow: Longman, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wrigley, N.; Lowe, M. Reading Retail: A Geographical Perspective on Retailing and Consumption Spaces; Arnold Publishers: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, R.; Mansvelt, J. New consumption geographies: Introduction to the special section. Geogr. Res. 2020, 58, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayne, M. Cities and Consumption; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Barata-Salgueiro, T.; Cachinho, H.; Guimarães, P. Introdução. In Comércio, Consumo & Governança Urbana; Barata-Salgueiro, T., Cachinho, H., Guimarães, P., Eds.; Centro de Estudos Geográficos, Universidade de Lisboa: Lisbon, Portugal, 2020; p. 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkip, F.; Kızılgün, Ö.; Mugan, G. The role of retailing in urban sustainability: The Turkish case. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2012, 20, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leontidou, L. Beyond the Borders of Mediterranean Cities: The Mediterranean City in Transition. ISIG J. Q. Int. Sociol. 2009, 18, 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro, L.; Sommella, R. La ricerca sul campo: Brevi riflessioni ed esperienze. In «Dentro» i Luoghi. Riflessioni ed Esperienze di Ricerca sul Campo; Lisi, R.A., Marengo, M., Eds.; Pacini: Pisa, Italy, 2009; p. 60. [Google Scholar]

- Viganoni, L. Commercio, Consumo e città. Quaderno di Lavoro; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Viganoni, L. Commercio e Consumo nelle Città che Cambiano. Napoli, Città Medie, Spazi Esterni; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sommella, R. Consumption and Retail in Urban Spaces: Studies on Italy and Catalonia. Bollett. Soc. Geogr. It. 2020, 14, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groncow, J.; Warde, A. Ordinary Consumption; Routledge: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zukin, S. Prefazione. In Nuovi Scenari per l’Attrattività delle Città e dei Territori; Ingallina, P., Ed.; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2017; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Leontidou, L.; Afouxenidis, A.; Kourliouros, E.; Marmaras, E. Infrastructure-related Urban Sprawl: Mega-events and Hybrid Peri-urban Landscapes in Southern Europe. In Urban Sprawl in Europe Landscapes, Land-Use Change & Policy; Couch, C., Leontidou, L., Petschel-Held, G., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 71–101. [Google Scholar]

- Sommella, R.; D’Alessandro, L. Consumption and Demand for Places: A Reading through the Neapolitan Case. Bollett. Soc. Geogr. It. 2020, 14, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J. Retail Geography, 3rd ed.; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Findlay, A.; Sparks, L. Far from the ‘Magic of the Mall’: Retail (Change) in ‘Other Places’. Scott. Geogr. J. 2012, 128, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coe, N.; Wrigley, N. Towards New Economic Geographies of Retail Globalization. In The New Oxford Handbook of Economic Geography; Clark, G.L., Feldman, M.P., Gertler, M.S., Wójcik, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 427–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

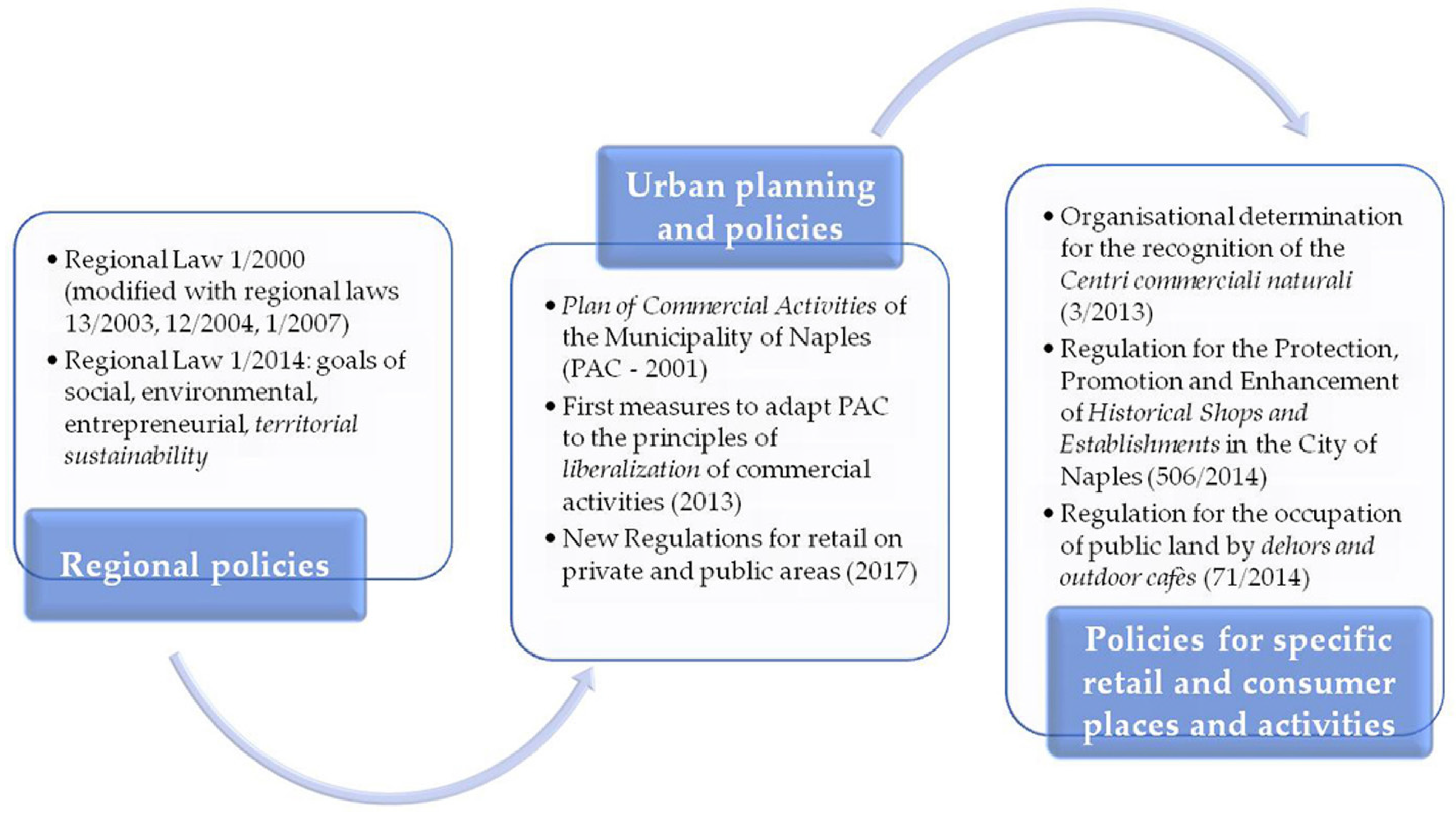

- D’Alessandro, L. Le politiche per il commercio: Scale, tempi, strumenti. In Commercio e Consumo nelle Città che Cambiano. Napoli, Città Medie, Spazi Esterni; Viganoni, L., Ed.; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2019; pp. 73–98. [Google Scholar]

- Barata-Salgueiro, T.; Erkip, F. Retail planning and urban resilience—An introduction to the special issue. Cities 2014, 36, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brunetta, G.; Salata, S. Mapping Urban Resilience for Spatial Planning—A First Attempt to Measure the Vulnerability of the System. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moraci, F.; Errigo, M.F.; Fazia, C.; Burgio, G.; Foresta, S. Making Less Vulnerable Cities: Resilience as a New Paradigm of Smart Planning. Sustainability 2018, 10, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cachinho, H.; Salgueiro, T.B. Os sistemas comerciais urbanos em tempos de turbulência: Vulnerabilidades e níveis de resiliência. Finisterra 2016, 51, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berry, B. Commercial Structure and Commercial Blight: Retail Patterns and Progresses in the City of Chicago; University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Whysall, P. Managing decline in inner city retail centres: From case study to conceptualization. Local Econ. 2011, 26, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, R.D.F.; Thomas, C.J. The Retail Revolution, the Carless Shopper and Disadvantage. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1993, 18, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.R.; Chamusca, P. Urban policies, planning and retail resilience. Cities 2014, 36, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachinho, H. Consumerscapes and the resilience assessment of urban retail systems. Cities 2014, 36, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weichselgartner, J.; Kelman, I. Geographies of resilience: Challenges and opportunities of a descriptive concept. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2015, 39, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stumpp, E.M. New in town? On resilience and “Resilient Cities”. Cities 2013, 32, 164–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.; Allam, Z.; Chabaud, D.; Gall, C.; Pratlong, F. Introducing the “15-Minute City”: Sustainability, Resilience and Place Identity in Future Post-Pandemic Cities. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata-Salgueiro, T. The Resilience of Urban Retail Areas. In Retail Planning for the Resilient City. Consumption and Urban Regeneration; Barata-Salgueiro, T., Cachinho, H., Eds.; Centro de Estudos Geográficos: Lisbon, Portugal, 2011; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Barata-Salgueiro, T.; Guimarães, P. Public Policy for Sustainability and Retail Resilience in Lisbon City Center. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolega, L.; Celińska-Janowicz, D. Retail resilience: A theoretical framework for understanding town centre dynamics. Stud. Reg. Lokal 2015, 2, 8–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrigley, N.; Dolega, L. Resilience, fragility, and adaptation: New evidence on the performance of UK high streets during global economic crisis and its policy implications. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2011, 43, 2337–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommella, R. Sostenibilità urbana e città mediterranee. In Sviluppo Sostenibile a Scala Regionale; Menegatti, B., Tinacci Mossello, M., Zerbi, M.C., Eds.; Pàtron: Bologna, Italy, 2000; p. 660. [Google Scholar]

- Leontidou, L. The Mediterranean City in Transition: Social Change and Urban Development; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Wrigley, N. Retail Geographies. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography; Kitchin, R., Thrift, N., Eds.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2009; pp. 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leontidou, L. Repolarization of the Mediterranean: Spanish and Greek cities in neo-liberal Europe. Eur. Plan. Stud. 1995, 3, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leontidou, L. Spaces of Risk, Spaces of Citizenship and Limits of the ‘Urban’ in European. In Proceedings of the Conference Lectured at the Symposium “(In)Visible Cities. Spaces of Hope, Spaces of Citizenship”, Centre of Contemporary Culture of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 25–27 July 2003; Available online: http://www.cccb.org/rcs_gene/spaces_risk.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Othengrafen, F.; Cotella, G.; Papaioannou, A.; Tulumello, S. Socio-political and socio-spatial impacts of the crisis in European cities and regions. In Cities in Crisis: Socio-Spatial Impacts of the Economic Crisis in Southern European Cities; Knieling, J., Othengrafen, F., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro, L. Le città mediterranee tra autenticità e ibridazioni. Civiltà del Mediterraneo 2018, 29, 185. [Google Scholar]

- Comune di Napoli (Municipality of Naples). La Struttura Demografica della Popolazione Residente nella Città di Napoli; Comune di Napoli: Naples, Italy, 2017. Available online: https://www.comune.napoli.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/34362 (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Comune di Napoli (Municipality of Naples). Rapporto UrBes Comunale di Napoli 2013; Comune di Napoli: Naples, Italy, 2014. Available online: http://www.comune.napoli.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/27920 our emphasis (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico (Ministry of Economic Development). Rapporto sul Sistema Distributivo Anno 2019; Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico: Rome, Italy, 2019. Available online: http://osservatoriocommercio.sviluppoeconomico.gov.it/Archivio_Rapporti/Rapporto_2019_web.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Associazione Studi e Ricerche per il Mezzogiorno (Study and Research Association for Southern Italy). La Nuova Distribuzione Commerciale nel Mezzogiorno; Giannini Editore: Naples, Italy, 2007; Available online: https://www.sr-m.it/wp-content/uploads/woocommerce_uploads/2015/09/ricerca_gdo.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Vona, R. La media distribuzione alimentare: Il nuovo commercio di prossimità. In Commercio, Consumo e Città. Quaderno di Lavoro; Viganoni, L., Ed.; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2017; pp. 143–149. [Google Scholar]

- Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico (Ministry of Economic Development). Rapporto sul Sistema Distributivo Anno 2010; Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico: Rome, Italy, 2010. Available online: http://osservatoriocommercio.sviluppoeconomico.gov.it/Archivio_Rapporti/Rapporto_2010Web.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Comune di Napoli (Municipality of Naples). Variante al Piano Regolatore Generale. Centro Storico, Zona Orientale, Zona Nord-occidentale; Comune di Napoli, Assessorato alla Vivibilità: Naples, Italy, 1999.

- Comune di Napoli (Municipality of Naples). Relazione alla Variante al Piano Regolatore Generale. Centro Storico, Zona Orientale, Zona Nord-Occidentale; Comune di Napoli: Naples, Italy, 2004. Available online: https://www.comune.napoli.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/1025 (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Della Lucia, M.; Trunfio, M. The role of the private actor in cultural regeneration: Hybridizing cultural heritage with creativity in the city. Cities 2018, 82, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, P.; Sommella, R.; Viganoni, L. Tra immagine e mercato. In La Forma e i Desideri. Saggi Geografici su Napoli e la Sua Area Metropolitana; Coppola, P., Ed.; Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane: Naples, Italy, 1997; pp. 235–251. [Google Scholar]

- Sommella, R. Las «lentas» transformaciones de los espacios centrales de Nápoles. In La Cuestión del Centro, el Centro en Cuestión; Martínez i Rigol, S., Ed.; Milenio: Lleida, Spain, 2009; pp. 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro, L. Comercio en el centro y consumo de centro en Nápoles. In La Cuestión del Centro, el Centro en Cuestión; Martínez i Rigol, S., Ed.; Milenio: Lleida, Spain, 2009; pp. 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro, L.; Sommella, L.; Viganoni, L. Film-Induced Tourism, City-Branding and Place-Based Image: The Cityscape of Naples between Authenticity and Conflicts. Almatourism 2015, 6, 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comune di Napoli (Municipality of Naples). Grande Progetto “Centro Storico di Napoli, Valorizzazione del Sito Unesco”; Comune di Napoli: Naples, Italy, 2012. Available online: https://www.comune.napoli.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/20994 (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Laino, G.; Lepore, D. Napoli: Una risposta alla crisi del governo urbano. In Le Agende Urbane delle Città Italiane. Secondo Rapporto sulle Città di Urban@it; Pasqui, G., Briata, P., Fedeli, V., Eds.; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2017; pp. 143–159. [Google Scholar]

- Sommella, R. Il territorio della ricerca: Fuori e dentro Napoli. In Commercio e Consumo nelle Città che Cambiano. Napoli, Città Medie, Spazi Esterni; Viganoni, L., Ed.; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2019; p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro, L. Il commercio su aree pubbliche tra degrado e riqualificazione: Napoli e i suoi mercati. Geotema 2009, 38, 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro, L. Attività Commerciali e Spazi Urbani. Per un Approccio Geografico al Centro Storico di Napoli; Guida: Naples, Italy, 2008; pp. 191–261. [Google Scholar]

- Comune di Napoli (Municipality of Naples). Il Piano di Gestione del Sito UNESCO “Centro Storico di Napoli”; Comune di Napoli: Naples, Italy, 2011. Available online: https://www.comune.napoli.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/24103 (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Amendola, G. Tra Dedalo e Icaro. La Nuova Domanda di Città; Laterza: Roma-Bari, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro, L.; Martínez-Rigol, S. Consumando spazi centrali e notti urbane: Micro-geografie dei giovani a Barcellona e a Napoli. Bollett. Soc. Geogr. It. 2018, 14, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comune di Napoli (Municipality of Naples). Map on the “Boundary of Historic Centre of Naples”: World Heritage Site and Buffer Zone; Comune di Napoli: Naples, Italy, 2011. Available online: https://www.comune.napoli.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/24103 (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- D’Alessandro, L.; Salaris, A. Retail as an Instrument for the Revitalization of City Center: Considerations from Two Italian Medium-sized Cities. In Retail Planning for the Resilient City. Consumption and Urban Regeneration; Barata-Salgueiro, T., Cachinho, H., Eds.; Centro de Estudos Geográficos: Lisbon, Portugal, 2011; pp. 299–315. [Google Scholar]

- Cozzi, T. Lockdown Fatale, La Repubblica Napoli, 19 May 2020. Available online: https://ricerca.repubblica.it/repubblica/archivio/repubblica/2020/05/19/lockdown-fatale-tarallo-decide-di-chiudereNapoli02.html (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- D’Alessandro, L. Micro-geografie di un’icona simbolica del commercio napoletano: Via Toledo tra mutamenti e contese. In Commercio e Consumo nelle Città che Cambiano. Napoli, Città Medie, Spazi Esterni; Viganoni, L., Ed.; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2019; pp. 289–314. [Google Scholar]

- Bridge, G.; Dowling, R. Microgeographies of Retailing and Gentrification. Aust. Geogr. 2001, 32, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachinho, H. Avenida da Liberdade: From the Burgeoisie Promenade to the Showcase of International Capital. In City, Retail and Consumption; D’Alessandro, L., Ed.; Università degli Studi di Napoli “L’Orientale”: Naples, Italy, 2015; pp. 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro, L.; Sommella, R.; Viganoni, L. Atmospheres of and in Geography. In Atmosphere/Atmospheres: Testing A New Paradigm; Griffero, T., Moretti, G., Eds.; Mimesis International: Milan, Italy, 2018; pp. 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Rigol, S. Can we talk about the retail gentrification. In L’Apporto della Geografia tra Rivoluzioni e Riforme; Salvatori, F., Ed.; A.Ge.I: Roma, Italy, 2019; pp. 2365–2373. [Google Scholar]

| 2010 | 2019 | % 2010–2019 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supermarkets | |||||

| Sales area | Employees | Sales area | Employees | Sales area | Employees |

| 47,110 | 988 | 67,044 | 1424 | 42.3 | 44.1 |

| Establishments | Franchising | Establishments | Franchising | Establishments | Franchising |

| 76 | 0 | 98 | 0 | 28.9 | 0 |

| Minimarkets | |||||

| Sales area | Employees | Sales area | Employees | Sales area | Employees |

| 20,904 | 493 | 32,465 | 765 | 55.3 | 55.2 |

| Establishments | Franchising | Establishments | Franchising | Establishments | Franchising |

| 74 | 0 | 114 | 0 | 54,1 | 0 |

| Department stores | |||||

| Sales area | Employees | Sales area | Employees | Sales area | Employees |

| 16,021 | 159 | 35,283 | 572 | 120.2 | 259.7 |

| Establishments | Franchising | Establishments | Franchising | Establishments | Franchising |

| 8 | 1 | 28 | 1 | 250 | 0 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sommella, R.; D’Alessandro, L. Retail Policies and Urban Change in Naples City Center: Challenges to Resilience and Sustainability from a Mediterranean City. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7620. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147620

Sommella R, D’Alessandro L. Retail Policies and Urban Change in Naples City Center: Challenges to Resilience and Sustainability from a Mediterranean City. Sustainability. 2021; 13(14):7620. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147620

Chicago/Turabian StyleSommella, Rosario, and Libera D’Alessandro. 2021. "Retail Policies and Urban Change in Naples City Center: Challenges to Resilience and Sustainability from a Mediterranean City" Sustainability 13, no. 14: 7620. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147620

APA StyleSommella, R., & D’Alessandro, L. (2021). Retail Policies and Urban Change in Naples City Center: Challenges to Resilience and Sustainability from a Mediterranean City. Sustainability, 13(14), 7620. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147620