Do National Values of Culture and Sustainability Influence Direct Employee PDM Levels and Scope? The Search for a European Answer

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Participative Decision Making (PDM)

2.2. Micro Level: Perceived Supervisor Support

2.3. Meso Level: Ownership and Size

2.4. Macro Level: Cultural Values and Sustainability

2.4.1. Power Distance

2.4.2. Individualism–Collectivism

2.4.3. Masculinity–Femininity

2.4.4. Time Orientation

2.4.5. Uncertainty Avoidance

2.4.6. Indulgence

2.4.7. Sustainability

3. Methods

3.1. Sample Selection

3.2. Measurement

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Independent Variables

3.2.3. Control Variables

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- PDM is influenced by factors from different levels (micro, meso, and macro), which show a wider and deeper analysis of determinants for participation initiatives, overall taking into account that all these levels have an impact on business activity and employee relations.

- In particular, macro analysis offers a special contribution because it considers all the Hofstede variables, which enriches the study by defining a cultural profile for European organizations according to their location. In this sense, it is worth mentioning how the power distance dimension is positively more significant when the operational PDM is analyzed. For its part, the value of the national culture of masculinity is negatively significant for both general PDM, as well as organizational and operational PDM. Additionally, the value of individualism is positively significant in all cases, turning out to be very similar for both the general PDM and the operational PDM. It is especially interesting, as the result of uncertainty avoidance is not significant in any of the three models analyzed. Furthermore, LTO obtains the highest negative significance value for the organizational PDM case.

- In addition, this perspective includes sustainability indexes, which have been gaining relevance in recent years due to the increase in awareness about environmental care. In this case, the coefficient obtained for the operational PDM model is significantly higher. This shows that European organizations, which are sensitive to sustainability, tend to promote autonomy at work.

- Precisely, this paper contributes to the existing literature expanding the concept of PDM and making differentiation in terms of the scope. In this respect, our results indicate that organizations located in countries with high levels of power distance, sustainability, and respect for traditions (LTO) tend to promote the autonomy of their employee in decision making involving their immediate tasks.

- Additionally, our study confirms that organizations located in countries focused on the short term will give the chance to employees to make decisions related to strategic issues.

7. Implications, Limitations, and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Delgado-Verde, M.; Martín-de Castro, G.; Emilio Navas-López, J. Organizational knowledge assets and innovation capability: Evidence from Spanish manufacturing firms. J. Intellect. Cap. 2011, 12, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rima’a, D. Participation in Decision Making and Affective Trust among the Teaching Staff: A 2-Year Cross-Lagged Structural Equation Modeling During Implementation Reform. Int. J. Educ. Reform 2020, 29, 77–97. [Google Scholar]

- Noah, Y. A Study of Worker Participation in Management Decision Making Within Selected Establishments in Lagos, Nigeria. J. Soc. Sci. 2008, 17, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talib, F.; Rahman, Z. Critical success factors of TQM in service organizations: A proposed model. Serv. Mark. Q. 2010, 31, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaed, M.M.B.; Zainol, I.N.B.H.; Yusof, M.B.M.; Bahrin, F.K. Types of Employee Participation in Decision Making (PDM) amongst the Middle Management in the Malaysian Public Sector. Int. J. Asian Soc. Sci. 2018, 8, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poole, M.; Lansbury, R.; Wailes, N. A comparative analysis of developments in industrial democracy. Ind. Relat. 2001, 40, 490–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markey, R.; Townsend, K. Contemporary trends in employee involvement and participation. J. Ind. Relat. 2013, 55, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, M.; Sypniewska, B. The impact of management methods on employee engagement. Sustainability 2020, 12, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cotton, J.L.; Vollrath, D.A.; Froggatt, K.L.; Lengnick-hall, M.L.; Jennings, K.R.; Cotton, J.L. Employee Participation: Diverse Forms and Different Outcomes Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2016, 13, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inanc, H.; Zhou, Y.; Gallie, D.; Felstead, A.; Green, F. Direct Participation and Employee Learning at Work. Work Occup. 2015, 42, 447–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gallie, D. Direct participation and the quality of work. Hum. Relat. 2013, 66, 453–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleberg, A.L.; Nesheim, T.; Olsen, K.M. Is participation good or bad for workers?: Effects of autonomy, consultation and teamwork on stress among workers in norway. Acta Sociol. 2009, 52, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jiang, J.Y. With whom shall I share my knowledge? A recipient perspective of knowledge sharing. J. Knowl. Manag. 2015, 19, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.R. “Gender Trouble”: Investigating gender and economic democracy in worker cooperatives in the united states. Rev. Radic. Polit. Econ. 2012, 44, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Sheaffer, Z.; Halevi, M.Y. Does participatory decision-making in top management teams enhance decision effectiveness and firm performance? Pers. Rev. 2009, 38, 696–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, L.; Drysdale, J.; Hughes, J. The future of leadership: A practitioner view. Eur. Manag. J. 2010, 28, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal Khan, T.; Ahmed Jam, F.; Akbar, A.; Bashir Khan, M.; Tahir Hijazi, S. Job Involvement as Predictor of Employee Commitment: Evidence from Pakistan. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 6, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valverde-Moreno, M.; Torres-Jiménez, M.; Lucia-Casademunt, A.M.; Muñoz-Ocaña, Y. Cross cultural analysis of direct employee participation: Dealing with gender and cultural values. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.G.; Shen, C.K. Perceived organizational support, participation in decision making, and perceived insider status for contract workers: A case study. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtessis, J.N.; Eisenberger, R.; Ford, M.T.; Buffardi, L.C.; Stewart, K.A.; Adis, C.S. Perceived Organizational Support: A Meta-Analytic Evaluation of Organizational Support Theory. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1854–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stinglhamber, F.; De Cremer, D.; Mercken, L. Perceived support as a mediator of the relationship between justice and trust: A multiple foci approach. Gr. Organ. Manag. 2006, 31, 442–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harel, G.; Tzafrir, S. HRM Practices in the Public and Private Sectors: Differences and Similarities. Public Adm. Q. 2001, 25, 316–355. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M.; Geddes, L.A.; Heywood, J.S. The determinants of employee-involvement schemes: Private sector Australian evidence. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2007, 28, 259–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Lee, N. Marketing in the Public Sector: The Final Frontier. Public Manag. 2007, 36, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dhir, S.; Shukla, A. The influence of personal and organisational characteristics on employee engagement and performance. Int. J. Manag. Concepts Philos. 2018, 11, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, L. Employee Participation in Europe. Manag. Learn. 1997, 28, 250–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albalate, J.J. Las restricciones a la participación de los trabajadores en las organizaciones empresariales. Pap. Rev. Sociol. 2001, 65, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arrindell, W. Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations. Behav. Res. Ther. 2003, 41, 861–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazer, S.; Karpati, T. The role of culture in decision making. Cut. IT J. 2014, 27, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Sagie, A.; Aycan, Z. A cross-cultural analysis of participative decision-making in organizations. Hum. Relat. 2003, 56, 453–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orji, I.J. Examining barriers to organizational change for sustainability and drivers of sustainable performance in the metal manufacturing industry. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 140, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahima, N.A.; Shah, S.I.U. Laboratory of CA micro-level implementation mechanism to enhance corporate sustainability performance: A social identity perspective. Int. J. Innov. Creat. Chang. 2020, 11, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bombiak, E.; Marciniuk-Kluska, A. Green human resource management as a tool for the sustainable development of enterprises: Polish young company experience. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ehnert, I.; Parsa, S.; Roper, I.; Wagner, M.; Muller-Camen, M. Reporting on sustainability and HRM: A comparative study of sustainability reporting practices by the world’s largest companies. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J. How green human resource management can promote green employee behavior in China: A technology acceptance model perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mazur, B. Sustainable Human Resource Management in theory and practice. Sustain. Hum. Resour. Manag. Theory Pract. 2014, 6, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, C.; Rizzi, F.; Frey, M. The role of sustainable human resource practices in influencing employee behavior for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 1221–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cugueró-Escofet, N.; Ficapal-Cusí, P.; Torrent-Sellens, J. Sustainable human resource management: How to create a knowledge sharing behavior through organizational justice, organizational support, satisfaction and commitment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karman, A. Understanding sustainable human resource management-organizational value linkages: The strength of the SHRM system. Hum. Syst. Manag. 2020, 39, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidescu, A.A.M.; Apostu, S.A.; Paul, A.; Casuneanu, I. Work flexibility, job satisfaction, and job performance among romanian employees-Implications for sustainable human resource management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Mesa, A.; Alegre, J. Entrepreneurial orientation and export intensity: Examining the interplay of organizational learning and innovation. Int. Bus. Rev. 2015, 24, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markey, R.; McIvor, J.; O’Brien, M.; Wright, C.F. Reducing carbon emissions through employee participation: Evidence from Australia. Ind. Relat. J. 2019, 50, 57–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Sousa e Silva, C.; Sousa, C. “Quality Box”, a way to achieve the employee involvement. In Proceedings of the Springer Proceedings in Mathematics and Statistics, XXIV IJCIEOM, Lisbon, Portugal, 18–20 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Falola, H.O.; Salau, O.P.; Olokundun, M.A.; Oyafunke-Omoniyi, C.O.; Ibidunni, A.S.; Oludayo, O.A. Employees’ intrapreneurial engagement initiatives and its influence on organisational survival. Bus. Theory Pract. 2018, 19, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurburg, D.; Viles, E.; Tanco, M.; Mateo, R.; Lleó, Á. Understanding the main organisational antecedents of employee participation in continuous improvement. TQM J. 2019, 31, 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanoni, P.; Janssens, M. Minority employees engaging with (diversity) management: An analysis of control, agency, and micro-emancipation. J. Manag. Stud. 2007, 44, 1371–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elele, J.; Fields, D. Participative decision making and organizational commitment: Comparing Nigerian and American employees. Cross Cult. Manag. 2010, 17, 368–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxall, P.; Hutchison, A.; Wassenaar, B. How do high-involvement work processes influence employee outcomes? An examination of the mediating roles of skill utilisation and intrinsic motivation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 26, 1737–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Zhai, X. Employee involvement in decision-making: The more the better? Int. J. Manpow. 2019, 40, 768–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, K.K.; Qureshi, T.M. Impact of Employee Participation on Job Satisfaction, Employee Commitment and Employee Productivity. Int. Rev. Bus. Res. Pap. 2007, 3, 54–68. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum, S.H.; Louis, D.; Makarenko, D.; Saluja, J.; Meleshko, O.; Kulbashian, S. Participation in decision making: A case study of job satisfaction and commitment (part three). Ind. Commer. Train. 2013, 45, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, A.; Gollan, P.J.; Marchington, M.; Lewin, D. Conceptualizing Employee Participation in Organizations; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lavelle, J.; Gunnigle, P.; McDonnell, A. Patterning employee voice in multinational companies. Hum. Relat. 2010, 63, 395–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, A.; Gollan, P.J.; Kalfa, S.; Xu, Y. Voices unheard: Employee voice in the new century. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 711–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zaware, N.; Pawar, A.; Kale, S.; Fauzi, T.; Loupias, H. Deliberating the managerial approach towards employee participation in management. Int. J. Control Autom. 2020, 13, 437–457. [Google Scholar]

- Ugwu, K.E.; Okoroji, L.I.; Chukwu, E.O. Participative decision making and employee performance in the hospitality industry: A study of selected hotels in Owerri Metropolis, Imo State. Manag. Stud. Econ. Syst. 2019, 4, 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Marchington, M.; Wilkinson, A. Direct Participation and Involvement. Manag. Hum. Resour. Pers. Manag. Transit. 2005, 398–423. [Google Scholar]

- Viveros, H.; Kalfa, S.; Gollan, P.J. Voice as an empowerment practice: The case of an Australian manufacturing company. In Advances in Industrial and Labor Relations; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen, H.; Busck, O.; Lind, J. Work environment quality: The role of workplace participation and democracy. Work. Employ. Soc. 2011, 25, 379–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sia, S.K.; Appu, A.V. Work Autonomy and Workplace Creativity: Moderating Role of Task Complexity. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2015, 16, 772–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busck, O.; Knudsen, H.; Lind, J. The transformation of employee participation: Consequences for the work environment. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2010, 31, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, J.B.; Tesluk, P.E.; Marrone, J.A. Shared leadership in teams: An investigation of antecedent conditions and performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 1217–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, C.L.; Conger, J.A.; Locke, E.A. Shared leadership theory. Leadersh. Q. 2008, 19, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Bock, G.W., Young-Gul, K., Eds.; Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, P.M. The Dynamics of Bureaucracy; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, M.C.; Kacmar, K.M. Discriminating among organizational politics, justice, and support. J. Organ. Behav. 2001, 22, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Bakar, H.; Mohamad, B.; Herman, I. Leader-Member Exchange and Superior-Subordinate Communication Behavior: A Case of a Malaysian Organization. Malays. Manag. J. 2020, 8, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torka, N.; Schyns, B.; Looise, J.K. Direct participation quality and organisational commitment: The role of leader-member exchange. Empl. Relat. 2010, 32, 418–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlgemuth, V.; Wenzel, M.; Berger, E.S.C.; Eisend, M. Dynamic capabilities and employee participation: The role of trust and informal control. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 37, 760–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, S.E.; Nahrgang, J.D.; Morgeson, F.P. Integrating Motivational, Social, and Contextual Work Design Features: A Meta-Analytic Summary and Theoretical Extension of the Work Design Literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1332–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nutt, P.C. Comparing public and private sector decision-making practices. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2006, 16, 289–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bercu, A. Strategic Decision Making in Public Sector: Evidence and Implications. Acta Univ. Danubius Acon. 2013, 9, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Nutt, P.C.; Backoff, R.W. Organizational publicness and its implications for strategic management. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diller, M. The Revolution in Welfare Administration: Rules, Discretion & Entrepreneurial Government. SSRN Electron. J. 2005, 75, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersley, B.; Alpin, C.; Forth, J.; Bryson, A.; Bewley, H.; Dix, G.; Oxenbridge, S. Inside the Workplace: Findings from the 2004 Workplace Employment Relations Survey; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, E.F.; Ortega, J.; Cabrera, Á. An exploration of the factors that influence employee participation in Europe. J. World Bus. 2003, 38, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McEvoy, G.M.; Buller, P.F. Human resource management practices in mid-sized enterprises. Am. J. Bus. 2013, 28, 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, H.; Calapez, T.; Lopes, D. The determinants of work autonomy and employee involvement: A multilevel analysis. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2015, 38, 448–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calantone, R.J.; Kim, D.; Schmidt, J.B.; Cavusgil, S.T. The influence of internal and external firm factors on international product adaptation strategy and export performance: A three-country comparison. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banham, H.C. External Environmental Analysis for Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). J. Bus. Econ. Res. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuznetsova, S.; Markova, V. New Challenges in External Environment and Business Strategy: The Case of Siberian Companies. Eurasian Stud. Bus. Econ. 2017, 4, 449–461. [Google Scholar]

- Coyle-Shapiro, J.A.M.; Shore, L.M. The employee-organization relationship: Where do we go from here? Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2007, 17, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schneider, S.C. Barsoux, J. Managing Across Cultures; Financial Times Prentice Hall: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Albaum, G.; Yu, J.; Wiese, N.; Herche, J.; Evangelista, F.; Murphy, B. Culture-based values and management style of marketing decision makers in six Western Pacific Rim countries. J. Glob. Mark. 2010, 23, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfand, M.J.; Erez, M.; Aycan, Z. Cross-cultural organizational behavior. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 479–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hofstede, G. Cultural dimensions in management and planning. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 1984, 1, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, L.M.; Sarkis, J. The role of employees’ leadership perceptions, values, and motivation in employees’ provenvironmental behaviors. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 196, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, B.; Chen, G.; Farh, J.L.; Chen, Z.X.; Lowe, K. Individual power distance orientation and follower reactions to transformational leaders: A cross-level, cross-cultural examination. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 744–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newburry, W.; Yakova, N. Standardization preferences: A function of national culture, work interdependence and local embeddedness. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2006, 37, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockner, J.; Ackerman, G.; Greenberg, J.; Gelfand, M.J.; Francesco, A.M.; Chen, Z.X.; Leung, K.; Bierbrauer, G.; Gomez, C.; Kirkman, B.L.; et al. Culture and Procedural Justice: The Influence of Power Distance on Reactions to Voice. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 37, 300–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kwon, B.; Farndale, E.; Park, J.G. Employee voice and work engagement: Macro, meso, and micro-level drivers of convergence? Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2016, 26, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Van de Vliert, E.; Van der Vegt, G. Breaking the Silence Culture: Stimulation of Participation and Employee Opinion Withholding Cross-nationally. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2005, 1, 459–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Connor, D.B.; Shimizu, M. Sense of personal control, stress and coping style: A cross-cultural study. Stress Health 2002, 18, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauta, M.M.; Liu, C.; Li, C. A cross-national examination of self-efficacy as a moderator of autonomy/job strain relationships. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 59, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Lawler, J.J.; Avolio, B.J. Leadership, individual differences, and workrelated attitudes: A cross-culture investigation. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 56, 212–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpaci, I.; Baloʇlu, M. The impact of cultural collectivism on knowledge sharing among information technology majoring undergraduates. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 56, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M. Hofstede’s cultural dimensions 30 years later: A study of Taiwan and the United States. Intercult. Commun. Stud. 2006, 15, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Melero, E. Are workplaces with many women in management run differently? J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fagenson, E.A.; Powell, G.N. Women and Men in Management. Adm. Sci. Q. 1989, 34, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luria, G.; Cnaan, R.A.; Boehm, A. National Culture and Prosocial Behaviors: Results from 66 Countries. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2015, 44, 1041–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, J.W.; Mitchell, T.R. Strategic Decision Processes: Comprehensiveness and Performance in an Industry with an Unstable Environment. Acad. Manag. J. 1984, 27, 399–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, D.P. Managerial determinants of decision speed in new ventures. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Lin, X.; Han, Z.R.; Tian, B.; Chen, G.Z.; Wang, H. The impact of future time orientation on employees’ feedback-seeking behavior from supervisors and co-workers: The mediating role of psychological ownership. J. Manag. Organ. 2015, 21, 336–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Cultural constraints in management theories. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1993, 7, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Bansal, P. Social responsibility in new ventures: Profiting from a long-term orientation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 1135–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, R.S.; Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations across Nations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, I.; Jie, C.; Zainal, M.; Harun, M.; Djubair, R.A. Effect of Power Distance and Uncertainty Avoidance on Employees’ Job Performance: Preliminary Findings. J. Technol. Manag. Bus. 2020, 2, 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner, T.A. The influence of national culture and organizational culture alignment on job stress and performance: Evidence from Greece. J. Manag. Psychol. 2001, 16, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, J.N.; Logsdon, J.M. Business ethics in the NAFTA countries: A cross-cultural comparison. J. Bus. Res. 2002, 55, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Sofware of the Mind, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Koc, E.; Ar, A.A.; Aydin, G. The Potential Implications of Indulgence and Restraint on Service. Ecoforum 2017, 6, 2013–2018. [Google Scholar]

- Valverde-Moreno, M.; Torres-Jimenez, M.; Lucia-Casademunt, A.M. Participative decision-making amongst employees in a cross-cultural employment setting: Evidence from 31 European countries. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2020, 45, 14–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, J.L.; Champion, D.; Daniels, K.J.; Dainty, A.J.D. An Institutional Theory perspective on sustainable practices across the dairy supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 152, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frynas, J.G.; Yamahaki, C. Corporate social responsibility: Review and roadmap of theoretical perspectives. Bus. Ethics 2016, 25, 258–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sarkis, J.; Zhu, Q.; Lai, K.H. An organizational theoretic review of green supply chain management literature. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 130, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Childe, S.J.; Papadopoulos, T.; Hazen, B.; Giannakis, M.; Roubaud, D. Examining the effect of external pressures and organizational culture on shaping performance measurement systems (PMS) for sustainability benchmarking: Some empirical findings. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 193, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renukappa, S.; Suresh, S.; Gabriel, M. External drivers for business model innovation for sustainability: An institutional theory perspective. J. Technol. Manag. Bus. 2020, 7, 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Fernando, Y.; Wah, W.X. The impact of eco-innovation drivers on environmental performance: Empirical results from the green technology sector in Malaysia. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2017, 12, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, M.; Gasparatos, A. Corporate environmental sustainability in the retail sector: Drivers, strategies and performance measurement. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, A.; Cagno, E.; Di Sebastiano, G.; Trianni, A. Industrial sustainability: Modelling drivers and mechanisms with barriers. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 194, 452–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.L. Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 946–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMD World Competitiveness Center. World Competiveness Yearbook; IMD World Competitiveness: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Elg, M.; Ellström, P.E.; Klofsten, M.; Tillmar, M. Sustainable development in Organizations. Sustain. Dev. Organ. Stud. Innov. Pract. 2015, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mehrzi, N.; Singh, S.K. Competing through employee engagement: A proposed framework. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2016, 65, 831–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, A.; Jena, L.K. Employee engagement as an enabler of knowledge retention: Resource-based view towards organisational sustainability. Int. J. Knowl. Manag. Stud. 2016, 7, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2015.

- Kottke, J.L.; Sharafinski, C.E. Measuring Perceived Supervisory and Organizational Support. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1988, 48, 1075–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanock, L.R.; Eisenberger, R. When supervisors feel supported: Relationships with subordinates’ perceived supervisor aupport, perceived organizational support, and performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, M.; Cregan, C. Organizational change cynicism: The role of employee involvement. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 47, 667–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-García, I.; Zúñiga-Vicente, J.Á. Strategic decision-making in secondary schools: The impact of a principal’s demographic profile. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timming, A.R. Tracing the effects of employee involvement and participation on trust in managers: An analysis of covariance structures. Int. J. of Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 3243–3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, A. Leading by Example: The Impact of Female Supervisors on Worker Productivity. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2016, 2016, 11724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.A. Using multi-item psychometric scales for research and practice in human resource management. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 57, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Delbridge, R.; Whitfield, K. Employee perceptions of job influence and organizational participation. Ind. Relat. 2001, 40, 472–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallie, D.; Felstead, A.; Green, F. Changing patterns of task discretion in Britain. Work. Employ. Soc. 2004, 18, 243–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| PDM | 0.01 | 0.44 |

| Supervisor_support | −0.05 | 1.02 |

| Power_distance | 54.71 | 20.25 |

| Masculinity | 48.56 | 21.93 |

| Individualism | 57.10 | 18.13 |

| Uncertainty_Avoidance | 73.29 | 19.78 |

| Long term orientation | 57.11 | 16.45 |

| Indulgence | 44.76 | 16.88 |

| Sustainability | 5.89 | 1.07 |

| Micro-Level Variables | PDM | PSS | Age | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 PDM | 1 | ||||||||||

| 2 PSS | 0.392 ** | 1 | |||||||||

| 3 Age | 0.055 ** | −0.053 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| Macro-Level variables | PDM | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||

| 4 Masculinity | −0.389 * | 1 | |||||||||

| 5 Power_distance | −0.516 ** | 0.187 | 1 | ||||||||

| 6 Individualism | 0.385 * | 0.132 | −0.588 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 7 Uncertainty_avoidance | −0.499 ** | 0.165 | 0.615 ** | −0.599 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 8 Long-term orientation | −0.438 * | 0.226 | 0.134 | 0.161 | 0.073 | 1 | |||||

| 9 Indulgence | 0.686 ** | −0.162 | −0.591 ** | 0.459 * | −0.53 ** | −0.329 | 1 | ||||

| 10 Sustainability | 0.448 * | −0.336 | −0.648 ** | 0.429 * | −0.539 ** | 0.078 | 0.486 ** | 1 | |||

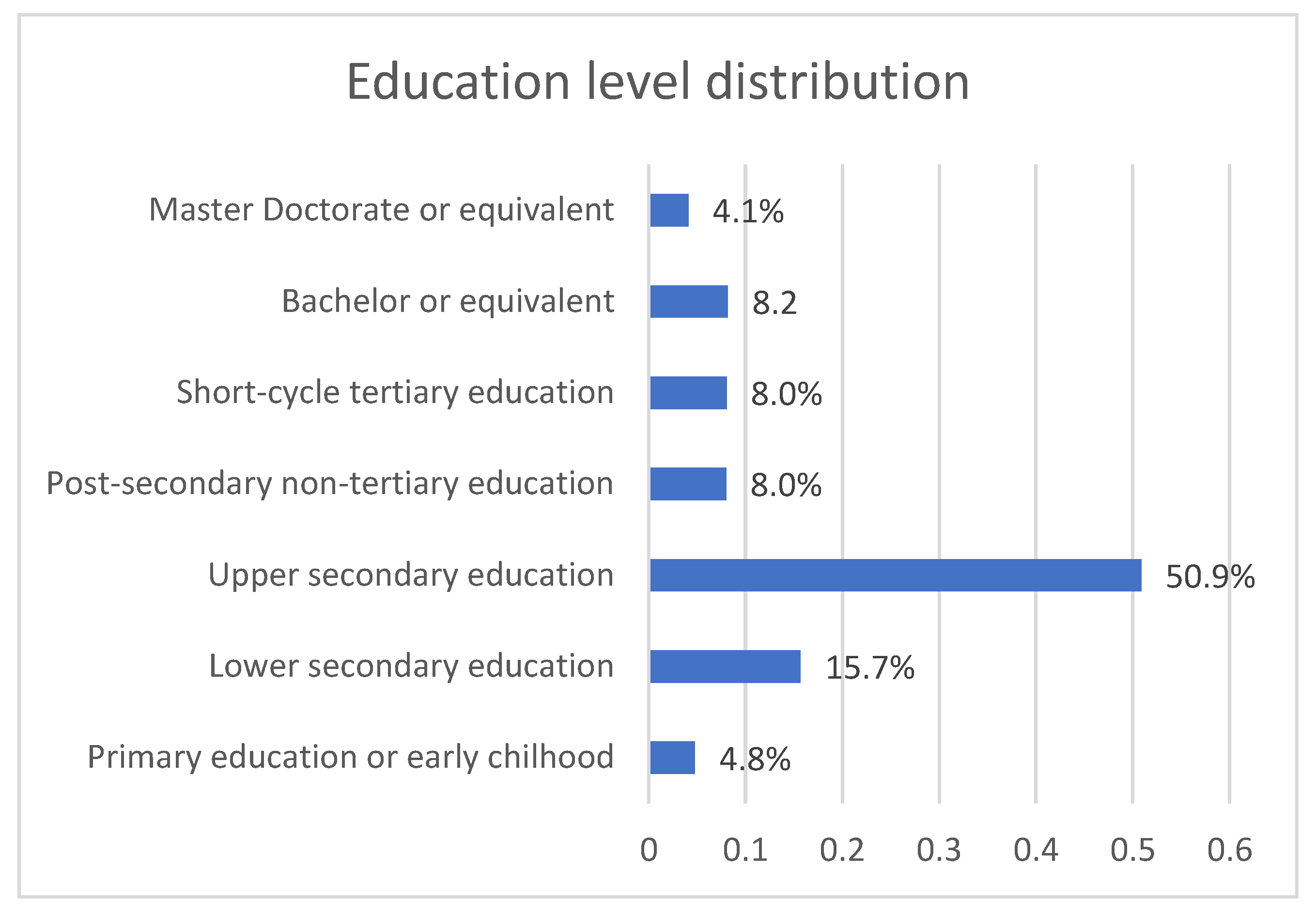

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General PDM | Organizational PDM | Operational PDM | ||

| Step 1: Control | Gender | −0.04 *** | −0.067 *** | 0.018 * |

| Age | 0.067 *** | 0.045 *** | 0.051 *** | |

| Secondary | 0.082 *** | 0.053 ** | 0.065 *** | |

| Post_secondary_non_terciary | 0.099 *** | 0.074 *** | 0.066 *** | |

| Short_cycle_t | 0.131 *** | 0.084 *** | 0.106 *** | |

| Bachelor | 0.157 *** | 0.114 *** | 0.111 *** | |

| Master_Doctorate | 0.147 *** | 0.112 *** | 0.096 *** | |

| Step 2: Control + Main Effect | Gender | −0.047 *** | −0.074 *** | 0.017 * |

| Age | 0.087 *** | 0.068 *** | 0.055 *** | |

| Secondary | 0.099 *** | 0.073 *** | 0.069 *** | |

| Post_secondary_non_tertiary | 0.102 *** | 0.078 *** | 0.067 *** | |

| Short_cycle_terciary | 0.134 *** | 0.087 *** | 0.107 *** | |

| Bachelor | 0.148 *** | 0.103 *** | 0.109 *** | |

| Master_Doctorate | 0.141 *** | 0.105 *** | 0.095 *** | |

| PSS | 0.388 *** | 0.428 *** | 0.086 *** | |

| Step 3: Controls + Main Effect + Organizational Variables | Gender | −0.052 *** | −0.075 *** | 0.012 *** |

| Age | 0.086 *** | 0.07 *** | 0.05 *** | |

| Secondary | 0.103 *** | 0.077 *** | 0.07 *** | |

| Post_secondary_non_tertiary | 0.104 *** | 0.081 *** | 0.066 *** | |

| Short_cycle_terciary | 0.136 *** | 0.092 *** | 0.105 *** | |

| Bachellor | 0.15 *** | 0.108 *** | 0.107 *** | |

| Master_Doctorate | 0.143 *** | 0.109 *** | 0.094 *** | |

| Supervisor_support | 0.385 *** | 0.426 *** | 0.083 *** | |

| Medium | −0.037 *** | −0.025 * | −0.029 ** | |

| Large | −0.053 *** | −0.04 *** | −0.035 *** | |

| Public | 0.034 *** | 0.006 * | 0.049 *** | |

| Step 4: Controls + Main Effect + Organizational variables+ Cultural values | Gender | −0.052 *** | −0.074 *** | 0.009 * |

| Age | 0.086 *** | 0.073 *** | 0.047 *** | |

| Secondary | 0.1 *** | 0.088 *** | 0.051 ** | |

| Post_secondary_non_tertiary | 0.099 *** | 0.083 *** | 0.054 *** | |

| Short_cycle_terciary | 0.12 *** | 0.088 *** | 0.082 *** | |

| Bachelor | 0.144 *** | 0.108 *** | 0.096 *** | |

| Master_Doctorate | 0.137 *** | 0.111 *** | 0.081 *** | |

| PSS | 0.381 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.083 *** | |

| Medium | −0.053 *** | −0.03 *** | −0.048 *** | |

| Large | −0.094 *** | −0.057 *** | −0.08 *** | |

| Public | 0.028 *** | 0.001 | 0.045 * | |

| Power_distance | −0.004 | 0.006 | −0.014 ** | |

| Masculinity | −0.096 *** | −0.056 *** | −0.084 *** | |

| Individualism | 0.095 *** | 0.052 *** | 0.089 *** | |

| Uncert Av | −0.011 * | 0.002 | −0.019 * | |

| LTO | 0.003 | −0.038 *** | 0.053 *** | |

| Indulgence | 0.058 *** | 0.027 ** | 0.06 *** | |

| Step 5: Controls + Main Effect + Organizational+ Cultural values + Institutional Factor | Gender | −0.053 *** | −0.073 *** | 0.008 * |

| Age | 0.085 *** | 0.073 *** | 0.045 *** | |

| Secondary | 0.097 *** | 0.089 *** | 0.045 ** | |

| Post_secondary_non_tertiary | 0.097 *** | 0.083 *** | 0.052 *** | |

| Short_cycle_terciary | 0.118 *** | 0.088 *** | 0.08 *** | |

| Bachelor | 0.144 *** | 0.108 *** | 0.096 *** | |

| Master_Doctorate | 0.134 *** | 0.111 *** | 0.076 *** | |

| PSS | 0.382 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.085 *** | |

| Medium | −0.053 *** | −0.03 *** | −0.048 *** | |

| Large | −0.094 *** | −0.057 *** | −0.08 *** | |

| Public | 0.03 *** | 0.001 | 0.047 *** | |

| Power_distance | 0.025 * | 0.004 | 0.035 ** | |

| Masculinity | −0.084 *** | −0.057 *** | −0.064 *** | |

| Individualism | 0.096 *** | 0.052 *** | 0.089 *** | |

| Uncert Av | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| LTO | −0.017 * | −0.037 *** | 0.019 * | |

| Indulgence | 0.049 *** | 0.027 ** | 0.046 *** | |

| Sustainability | 0.06 *** | −0.003 | 0.101 *** | |

| Hypotheses | Consecution |

|---|---|

| Hypothesis 1 (H1). PSS relates positively to direct employee participation. | Accepted |

| Hypothesis 1a (H1a). PSS relates positively to organizational direct employee participation. | Accepted |

| Hypothesis 1b (H1b). PSS relates positively to operational direct employee participation. | Accepted |

| Hypothesis 2 (H2). The public sector tends to promote PDM less than private sector. | Rejected |

| Hypothesis 2a (H2a). The public sector tends to promote organizational PDM less than private sector. | No significant relation was found |

| Hypothesis 2b (H2b). The public sector tends to promote operational PDM more than private sector. | Accepted |

| Hypothesis 3 (H3). Organization size is positively related to PDM. | Rejected |

| Hypothesis 3a (H3a). Organization size is positively related to organizational PDM. | Rejected |

| Hypothesis 3b (H3b). Organization size is negatively related to operational PDM. | Rejected |

| Hypothesis 4 (H4). The higher the level of power distance, the lower the level of employee participation in that country. | Accepted |

| Hypothesis 4a (H4a). The higher the level of power distance, the lower the level of employee organizational participation in that country. | No significant relation was found |

| Hypothesis 4b (H4b). The higher the level of power distance, the lower the level of employee operational participation in that country. | Accepted |

| Hypothesis 5 (H5). The higher the level of individualism,the lower the level of employee participation in that country. | Rejected |

| Hypothesis 5a (H5a). The higher the level of individualism, the lower the level of organizational employee participation in that country. | Rejected |

| Hypothesis 5b (H5b). The higher the level of individualism, the higher the level of operational employee participation in that country. | Accepted |

| Hypothesis 6 (H6). The higher the level of male values in the country where the organization is located, the lower the level of employee participation. | Accepted |

| Hypothesis 6a (H6a). The higher the level of male values in the country where the organization is located, the lower the level of operational employee participation. | Accepted |

| Hypothesis 6b (H6b). The higher the level of male values in the country where the organization is located, the lower the level of organizational employee participation. | Accepted |

| Hypothesis 7 (H7). The higher the level of long-term orientation in the country where the organization is located, the greater the employee participation in that organization. | Rejected |

| Hypothesis 7a (H7a). The higher the level of long-term orientation in the country where the organization is located, the lower the operational employee participation in that organization. | Rejected |

| Hypothesis 7b (H7b). The higher the level of long-term orientation in the country where the organization is located, the greater the organizational employee participation in that organization. | Rejected |

| Hypothesis 8 (H8). The higher the level of uncertainty avoidance, the lower the level of employee participation in that country. | No significant relation was found |

| Hypothesis 8a (H8a). The higher the level of uncertainty avoidance, the lower the level of organizational employee participation in that country. | No significant relation was found |

| Hypothesis 8b (H8b). The higher the level of uncertainty avoidance, the lower the level of operational employee participation in that country. | No significant relation was found |

| Hypothesis 9 (H9). The higher the level of indulgence, the higher the level of employee participation in that country. | Accepted |

| Hypothesis 9a (H9a). The higher the level of indulgence, the higher the level of organizational employee participation in that country. | Accepted |

| Hypothesis 9b (H9b). The higher the level of indulgence, the higher the level of operational employee participation in that country. | Accepted |

| Hypothesis 10 (H10). The sustainability levels of the country where organizations are located are positively related to employee participation in PDM. | Accepted |

| Hypothesis 10a (H10a). The sustainability levels of the country where organizations are located are positively related to organizational employee participation. | No significant relation was found |

| Hypothesis 10b (H10b). The sustainability levels of the country where organizations are located are positively related to operational employee participation. | Accepted |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valverde-Moreno, M.; Torres-Jiménez, M.; Lucia-Casademunt, A.M.; Pacheco-Martínez, A.M. Do National Values of Culture and Sustainability Influence Direct Employee PDM Levels and Scope? The Search for a European Answer. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8016. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13148016

Valverde-Moreno M, Torres-Jiménez M, Lucia-Casademunt AM, Pacheco-Martínez AM. Do National Values of Culture and Sustainability Influence Direct Employee PDM Levels and Scope? The Search for a European Answer. Sustainability. 2021; 13(14):8016. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13148016

Chicago/Turabian StyleValverde-Moreno, Marta, Mercedes Torres-Jiménez, Ana M. Lucia-Casademunt, and Ana María Pacheco-Martínez. 2021. "Do National Values of Culture and Sustainability Influence Direct Employee PDM Levels and Scope? The Search for a European Answer" Sustainability 13, no. 14: 8016. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13148016

APA StyleValverde-Moreno, M., Torres-Jiménez, M., Lucia-Casademunt, A. M., & Pacheco-Martínez, A. M. (2021). Do National Values of Culture and Sustainability Influence Direct Employee PDM Levels and Scope? The Search for a European Answer. Sustainability, 13(14), 8016. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13148016