Resilience, Leadership and Female Entrepreneurship within the Context of SMEs: Evidence from Latin America

Abstract

:1. Introduction

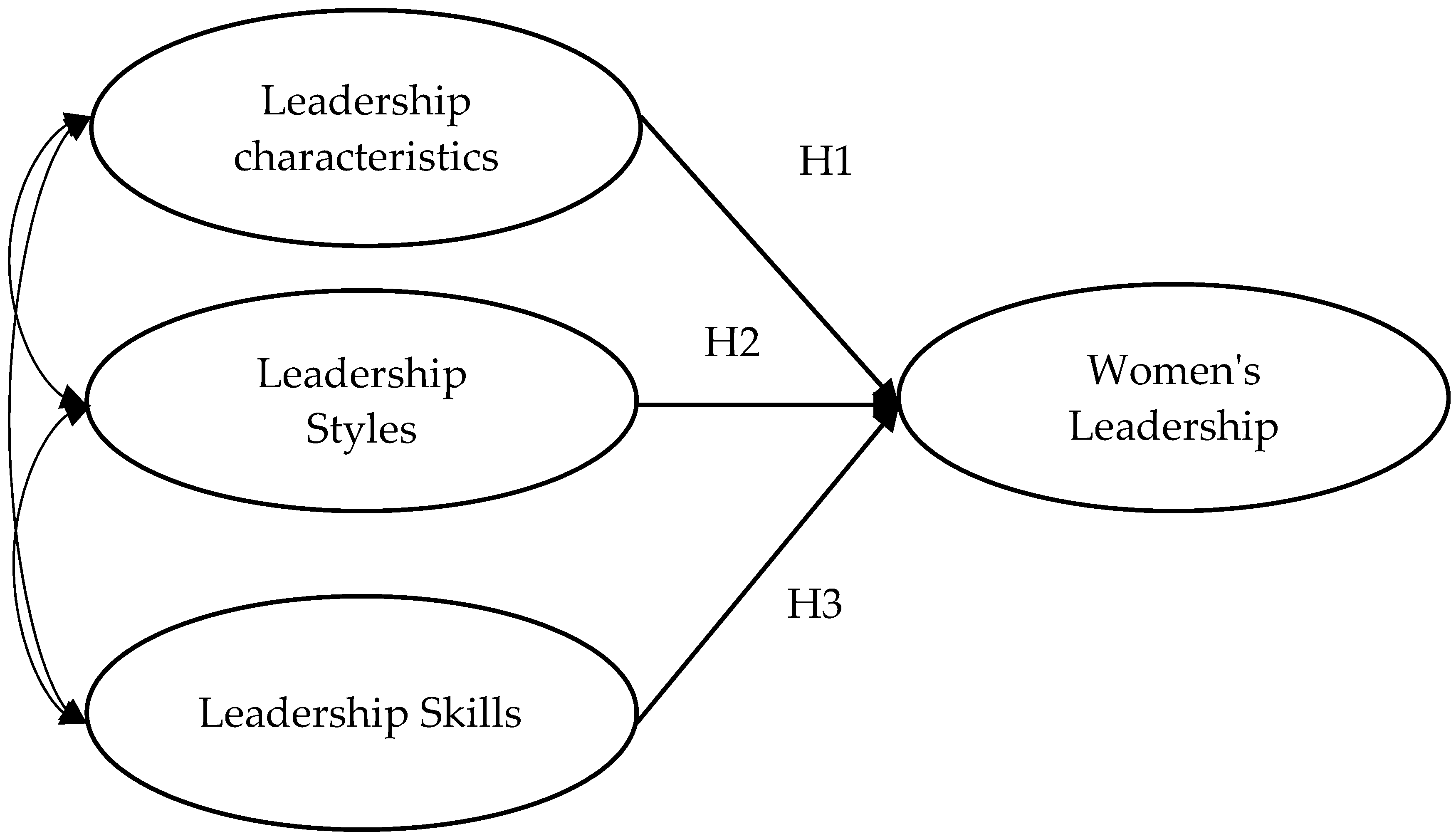

- Hypothesis 1 (H1).Leadership characteristics influence female leadership in those SMEs that are dedicated to the organization of Wayuu handicrafts.

- Hypothesis 2 (H2).Leadership styles are related to female leadership in those SMEs that are dedicated to Wayuu handicrafts.

- Hypothesis 3 (H3).Leadership skills influence the development of female leadership in Wayuu handicraft marketing SMEs.

2. Background

2.1. Resilient Female Leadership and Its Distinctive Approach to Manage Small and Medium-Sized Wayuu Handicraft Enterprises

2.2. Characteristic Styles of Female Leadership in the Management of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises That Market Wayuu Handicrafts

2.3. Skills Developed by Women Entrepreneurs in the Management of Small and Medium-Sized Wayuu Handicraft Trading Companies

- Conceptual ability: The leader is able to see the organization as a whole, in which the parts complement each other; in this case, it regards the relationship of the company with another one. According to authors’ criteria, conceptual ability is the mental capacity to coordinate diverse interests and activities. It means having the capacity of abstract thinking, of analyzing information, and of establishing connections between data [43,46]; therefore, the manager must achieve critical thinking and conceptualize things with respect to how they could be. The authors highlight how the practice of the analyzed companies shows the relational abilities and the capacity of creating alliances, in order to work with strategies favoring the common good.

- Technical competencies: Technical competencies are the set of knowledge, experiences, and skills that are necessary to adequately fulfill the requirements of their positions [43,47]. The skills represented by technical competencies, which are associated with tools, procedures, and techniques specific to their situation of specialization, are necessary to master their work. In the analyzed companies, the technical competencies of female leadership derive from their practical experience and from the setting of strategies to carry out the work plan.

- Human competencies: Human skills that the leader has to master to perceive the strengths of the human talents in the organization. Some authors underline that human relations skills focus on the aptitude to work together, to understand, and to motivate people in the workplace [43,48]. The importance of assertive and effective communication is emphasized, through a vision shared with collaborators, by listening to what they have to say and by guiding, facilitating, and supporting people in the workplace.

2.4. Leadership Styles in the Entrepreneurship of Women Marketers of Wayuu Handicrafts

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Novalbos Ruiz, J. Las Bibliotecas Públicas Españolas ante los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible de las Naciones Unidas «Agenda 2030». Master’s Thesis, University of Extremadura, Badajoz, Spain, 2021. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10662/11761 (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- González-Díaz, R.R.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Salazar-Sepúlveda, G.; Castillo, D. Contributions of Subjective Well-Being and Good Living to the Contemporary Development of the Notion of Sustainable Human Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez, T.V. Women, defenders of equality and care for nature. iQual. Revista Género Igualdad 2021, 4, 35–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiró, J.M.; Ayala, Y.; Tordera, N.; Lorente, L.; Rodríguez, I. Bienestar sostenible en el trabajo: Revisión y reformulación [Sustainable wellness at work: Review and reformulation]. Papeles Psicólogo 2014, 35, 5–14. Available online: http://www.papelesdelpsicologo.es (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Di Fabio, A.; Peiró, J.M. Human Capital Sustainability Leadership to Promote Sustainable Development and Healthy Organizations: A New Scale. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Fabio, A.; Bucci, O.; Gori, A. High Entrepreneurship, Leadership, and Professionalism (HELP): Towards an integrated, empirically based perspective. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- D’Adamo, I.; Lupi, G. Sustainability and Resilience after COVID-19: A Circular Premium in the Fashion Industry. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benites, M.; González-Díaz, R.R.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Becerra-Pérez, L.A.; Tristancho Cediel, G. Latin American Microentrepreneurs: Trajectories and Meanings about Informal Work. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joga-Elvira, L.; Jacas, C.; Joga, M.L.; Roche-Martínez, A.; Brun-Gasca, C. Pilot study of socio-emotional factors and adaptive behavior in young females with fragile X syndrome. Child Neuropsychol. 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, E. Would Overconfident CEOs Engage More in Environment, Social, and Governance Investments? With a Focus on Female Representation on Boards. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Wu, Y.; Mehmood, K.; Jabeen, F.; Iftikhar, Y.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Kwan, H.K. Impact of Spectators’ Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility on Regional Attachment in Sports: Three-Wave Indirect Effects of Spectators’ Pride and Team Identification. Sustainability 2021, 13, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolinek, L.; Kopta, D.; Plevny, M.; Rost, M.; Kubecova, J. Level of process management implementation in SMEs and some related implications. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2015, 14, 360–377. [Google Scholar]

- Caruso, G.; Gattone, S.A.; Fortuna, F.; Di Battista, T. Cluster Analysis for mixed data: An application to credit risk evaluation. Socio Econ. Plan. Sci. 2021, 73, 100850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabula, J.B.; Dongping, H.; Mwakapala, L.Y. SME’s use of I.C.T. and financial services on innovation performance: The mediating role of managers’ experience. Hum. Syst. Manag. 2020, 39, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajrami, D.D.; Radosavac, A.; Cimbaljević, M.; Tretiakova, T.N.; Syromiatnikova, Y.A. Determinants of 580 residents’ support for sustainable tourism development: Implications for rural communities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, Á.E.; Vergara, O.; González, Y. Responsible Marketing: Distinctive Advantage in the Value Chain of Organizations. J. Manag. Bus. Stud. 2019, 1, 44–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Gutiérrez, E.-J.; Valle Flórez, R.E.; Terrón Bañuelos, E.; Centeno Suárez, B. El liderazgo femenino y su ejercicio en las organizaciones educativas. Iberoam. J. Educ. 2003, 33, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, P.K.; Roberts, H.; Stainback, K. Does women’s board representation affect non-managerial gender inequality? Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G. A typology for the case study in social science following a review of definition, discourse, and structure. Qual. Inq. 2011, 17, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadi-Montiel, O.; Acevedo-Duque, A. Liderazgo ético frente a la diversidad cultural dentro de las organizaciones con régimen disciplinario. Económicas CUC 2014, 35, 75–88. Available online: https://revistascientificas.cuc.edu.co/economicascuc/article/view/522 (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- González-Díaz, R.R.; Guanilo-Gómez, S.L.; Acevedo-Duque, E.; Campos, J.S.; Cachicatari Vargas, E. Intrinsic alignment with strategy as a source of business sustainability in S.M.E.s. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2021, 8, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, J.M.; Cyr, D.; Burton, L.J. Microaggressions in administrator preparation programs: How black female participants experienced discussions of identity, discrimination, and leadership. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, N.; Kazumi, T. Female entrepreneurs’ cognitive attributes and venture growth in Japan: The moderating role of perceived social legitimacy. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Müller, S.; Kalia, P.; Mehmood, K. Predictive Sustainability Model Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior Incorporating Ecological Conscience and Moral Obligation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigil, K.M. Warrior Women: Recovering Indigenous Visions across Film and Activism. JCMS J. Cine. Media Stud. 2021, 60, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russomanno, J.; Tree, J.M.J.T.J. Assessing sense of community at farmers markets. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2021, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P.; Chatpinyakoop, C. A Bibliometric Review of Research on Higher Education for Sustainable Development, 1998–2018. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- D’Adamo, I.; Falcone, P.M.; Imbert, E.; Morone, P. A Socio-economic Indicator for EoL Strategies for Bio-based Products. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 178, 106794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I.; Rosa, P. How Do You See Infrastructure? Green Energy to Provide Economic Growth after COVID-19. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolasso, P. Desigualdad y fragmentación territorial en América Latina. J. Lat. Am. Geogr. 2020, 19, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiz-Álvarez, J.M.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Castillo, D. B Corps: A Socioeconomic Approach for the COVID-19 Post-crisis. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaulay, B.S.; Krishnamoorthy, S. (Re)imagined Possibilities: The Resilience of the Black Woman Griot, Zeinabu irene Davis in Conversation. Fem. Media Hist. 2021, 7, 81–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrchota, J.; Řehoř, P.; Marikova, M.; Pech, M. Critical Success Factors of the Project Management in Relation to Industry 4.0 for Sustainability of Projects. Sustainability 2021, 13, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Kim, S.; You, J.; Han, H.; Kim, M.; Yoon, S. How South Korean women leaders respond to their token status: Assimilation and resistance. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2021, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Perez-Lugo, M.; Garcia, C.O.; Crespo, F.G.; Castillo, A. Empowered Stakeholders: Female University Students’ Leadership During the COVID-19-Triggered On-campus Evictions in Canada and the United States. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, B.B.; Hasan, I.; Shen, Y.V.; Wu, Q. Do activist hedge funds target female CEOs? The role of CEO gender in hedge fund activism. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 141, 372–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, R.; Verge, T. The symbolic representation of women’s political firsts in editorial cartoons. Fem. Media Stud. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šípová-Jungová, H.; Jurgová, L.; Hemmerová, E.; Homola, J. Interaction of Tris with D.N.A. molecules and carboxylic groups on self-assembled monolayers of alkanethiols measured with surface plasmon resonance. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 546, 148984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherneski, J. Zebras showing their stripes: A critical sense-making study of women C.S.R. leaders. Qual. Res. Organ. Manag. Int. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimal, K.E.K.; Kandasamy, J.; Duque, A.A. Integrating sustainability and remanufacturing strategies by remanufacturing quality function deployment (RQFD). Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osi, E.C.; Teng-Calleja, M. Women on top: The career development journey of Filipina business executives in the Philippines. Career Dev. Int. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, S.; Assmann, K. The “ProQuote” initiative: Women journalists in Germany push to revolutionise newsroom leadership. Fem. Media Stud. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Luke, N.; Short, S.E. Women’s Political Leadership and Adult Health: Evidence from Rural and Urban China. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2021, 62, 100–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahin, M.; Ilic, O.; Gonsalvez, C.; Whittle, J. The impact of a STEM-based entrepreneurship program on the entrepreneurial intention of secondary school female students. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leschber, G. From female surgical resident to academic leaders: Challenges and pathways forward. J. Thorac. Dis. 2021, 13, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malloy, E.; Kavussanu, M. A comparison of authentic and transformational leadership in sport. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolpakov, A.; Boyer, E. Examining Gender Dimensions of Leadership in International Nonprofits. Public Integr. 2021, 23, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G. Michelle Bachelet’s Liderazgo Femenino (Feminine Leadership) redefining political leadership in Chile’s 2005 presidential campaign. Int. Fem. J. Politics 2011, 13, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helming, S.; Ungermann, F.; Hierath, N.; Stricker, N.; Lanza, G. Development of a training concept for leadership 4.0 in production environments. Procedia Manuf. 2019, 31, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotter, J.P. La Verdadera Labor de un Líder. Ed. Norma SA. Colombia. 1999. Available online: https://books.google.rs/books?hl=sr&lr=&id=hcIeWS-2kQgC&oi=fnd&pg=PA39&dq=La+verdadera+labor+de+un+l%C3%ADder&ots=miNe5HnGWS&sig=TotyQYwi6NW6Fe8pNbqEUnAVB40&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=La%20verdadera%20labor%20de%20un%20l%C3%ADder&f=false (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Fitzgerald, T. Changing the deafening silence of indigenous women’s voices in educational leadership. J. Educ. Adm. 2003, 41, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Landa, D.; Tyson, S.A. Coercive leadership. Am. J. Political Sci. 2017, 61, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornelas, R. Water and the Indigenous Women’s Leadership Project. 2011. Available online: https://digital.library.txstate.edu/handle/10877/12841 (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Davies, B.; Brighouse, T. Passionate leadership. Manag. Educ. 2010, 24, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, M.E.; Karlsen, J.T. A study of coaching leadership style practice in projects. Manag. Res. Rev. 2016, 39, 1122–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Meagher, K.; El Achi, N.; Ekzayez, A.; Sullivan, R.; Bowsher, G. Having more women humanitarian leaders will help transform the humanitarian system: Challenges and opportunities for women leaders in conflict and humanitarian health. Confl. Health 2020, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffari, A.; Lee, J.; Kim, E. Variability Modeling in Software Product Line: A Systematic Literature Review. In Software Engineering in IoT, Big Data, Cloud and Mobile Computing. Studies in Computational Intelligence; Kim, H., Lee, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Gonzalez-Diaz, R.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Fernández Mantilla, M.M.; Ovalles-Toledo, L.V.; Cachicatari-Vargas, E. The Role of B Companies in Tourism towards Recovery from the Crisis COVID-19 Inculcating Social Values and Responsible Entrepreneurship in Latin America. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.W.; Hill, S.S.; Fields, A.C.; Davids, J.S.; Melnitchouk, N. Factors associated with the professional success of female surgical department chairs: A qualitative study. JAMA Surg. 2020, 155, 1028–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Loarne-Lemaire, S.; Bertrand, G.; Razgallah, M.; Maalaoui, A.; Kallmuenzer, A. Women in innovation processes as a solution to climate change: A systematic literature review and an agenda for future research. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 120440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flory, J.A.; Leibbrandt, A.; Rott, C.; Stoddard, O. Increasing Workplace Diversity Evidence from a Recruiting Experiment at a Fortune 500 Company. J. Hum. Resour. 2021, 56, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulmer, E.; Riera, M.; Rodríguez, R. The Importance of Sustainable Leadership amongst Female Managers in the Spanish Logistics Industry: A Cultural, Ethical and Legal Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlea-Schiopoiu, A.; Mihai, L.S. An Integrated Framework on the Sustainability of SMEs. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miliopoulou, G.Z.; Kapareliotis, I. The toll of success: Female leaders in the “women-friendly” Greek advertising agencies. Gend. Work. Organ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterbenk, Y.; Champlin, S.; Windels, K.; Shelton, S. Is Femvertising the New Greenwashing? Examining Corporate Commitment to Gender Equality. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozhinov, V.; Joecks, J.; Scharfenkamp, K. Gender spillovers from supervisory boards to management boards. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, P.; Bird, M.D.; Farber, V. Gender and entrepreneurial propensity: Risk-taking and prosocial preferences in labour market entry decisions. Soc. Enterp. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, D.M.; Alam, M.S.; Mazumder, M.M.M.; Amin, A. Gender-related discourses in corporate annual reports: An exploratory study on the Bangladeshi companies. J. Account. Organ. Chang. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigol, T. Gender Differences in Engagement in Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior—Two Studies in Poland. Sustainability 2021, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M. Women Engineers on Their Way to Leadership: The Role of Social Support Within Engineering Work Cultures. Eng. Stud. 2021, 13, 30–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.; König, C.J.; Zobel, Y. Executive Search Consultants’ Biases Against Women (or Men?). Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 541766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldner, C.; Pierro, A. The trials of women leaders in the workforce: How a need for cognitive closure can influence acceptance of harmful gender stereotypes. Sex Roles 2019, 80, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, P.K.; Roberts, H.; Whiting, R.H. Female directors and C.S.R. disclosure in Bangladesh: The role of family affiliation. Meditari Account. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshmery, S.N.; Alqirnas, H.R.; Alyuosef, M.I. Influence of the social and economic characteristics of Saudi women on their attitudes toward empowering them in online labor market. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riner, A.N.; Herremans, K.M.; Neal, D.W.; Johnson-Mann, C.; Hughes, S.J.; McGuire, K.P.; Upchurch, G.R., Jr.; Trevino, J.G. Diversification of Academic Surgery, Its Leadership, and the Importance of Intersectionality. JAMA Surg. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Masi, S.; Słomka-Gołębiowska, A.; Paci, A. Women on boards and monitoring tasks: An empirical application of Kanter’s theory. Manag. Decis. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uduji, J.I.; Okolo-Obasi, E.N.; Asongu, S.A. Sustaining cultural tourism through higher female participation in Nigeria: The role of corporate social responsibility in oil host communities. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 120–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caruso, G.; Fortuna, F. Mediterranean diet Patterns in the Italian Population: A functional data analysis of Google Trends. Decis. Trends Soc. Syst. 2020, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appolloni, A.; Colasanti, N.; Fantauzzi, C.; Fiorani, G.; Frondizi, R. Distance Learning as a Resilience Strategy during Covid-19: An Analysis of the Italian Context. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I.; González-Sánchez, R.; Medina-Salgado, M.S.; Settembre-Blundo, D. E-Commerce Calls for Cyber-Security and Sustainability: How European Citizens Look for a Trusted Online Environment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudice, F.; Caferra, R.; Morone, P. COVID-19, the Food System and the Circular Economy: Challenges and Opportunities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, P.; Paul, S.K.; Azeem, A.; Chowdhury, P. Evaluating Supply Chain Collaboration Barriers in Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzemieniak, M.; Wawer, M. Employer Branding in the Context of the Company’s Sustainable Development Strategy from the Perspective of Gender Diversity of Generation Z. Sustainability 2021, 13, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, A.; Bustamante, G.; Salazar, G. Orange Economy and Digital Entrepreneurship in Latin America: Creative Sparkles among Raw Materials, Chapter 10. In Handbook of Research on Digital Marketing Innovations in Social Entrepreneurship and Solidarity Economics; Saiz-Alvarez, J.M., Ed.; I.G.I. Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 182–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Ramírez, E.; Barba-Sánchez, V. Embeddedness as a Differentiating Element of Indigenous Entrepreneurship: Insights from Mexico. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, I.; Appolloni, A.; Chirico, A.; Cheng, W. The role of the environmental dimension in the performance management system: A systematic review and conceptual framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

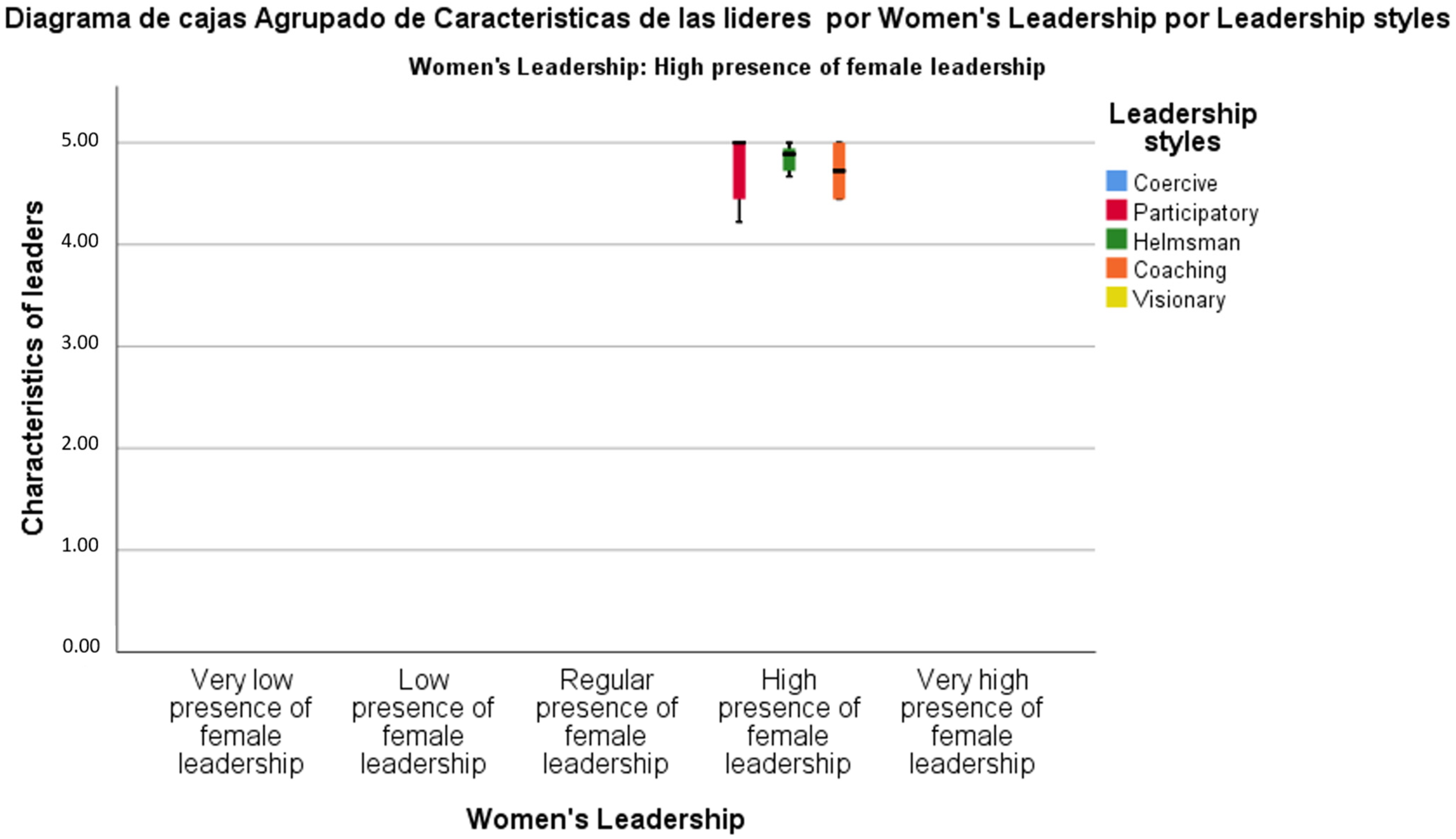

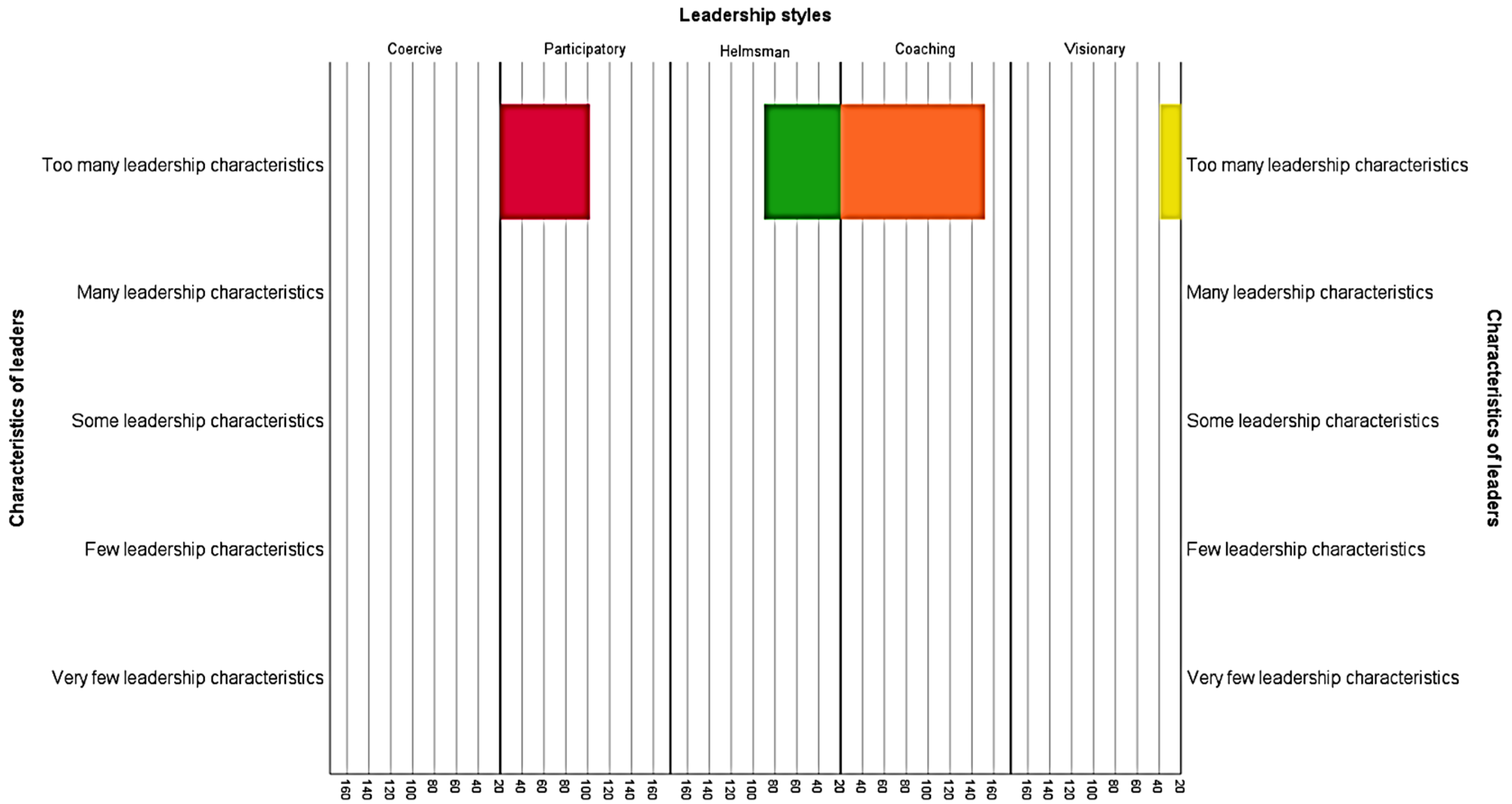

| Rank | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| Variable: Female Leadership | |

| Min–1.80 | Deficient presence of female leadership. |

| 1.81–2.60 | Low presence of female leadership |

| 2.61–3.40 | The regular presence of female leadership. |

| 3.41–4.20 | High presence of female leadership. |

| 4.21–Max | Very high presence of female leadership. |

| Dimension: Characteristics | |

| Min–1.80 | Very few leadership characteristics. |

| 1.81–2.60 | Few leadership characteristics |

| 2.61–3.40 | Some leadership characteristics |

| 3.41–4.20 | Many leadership characteristics. |

| 4.21–Max | Too many leadership characteristics. |

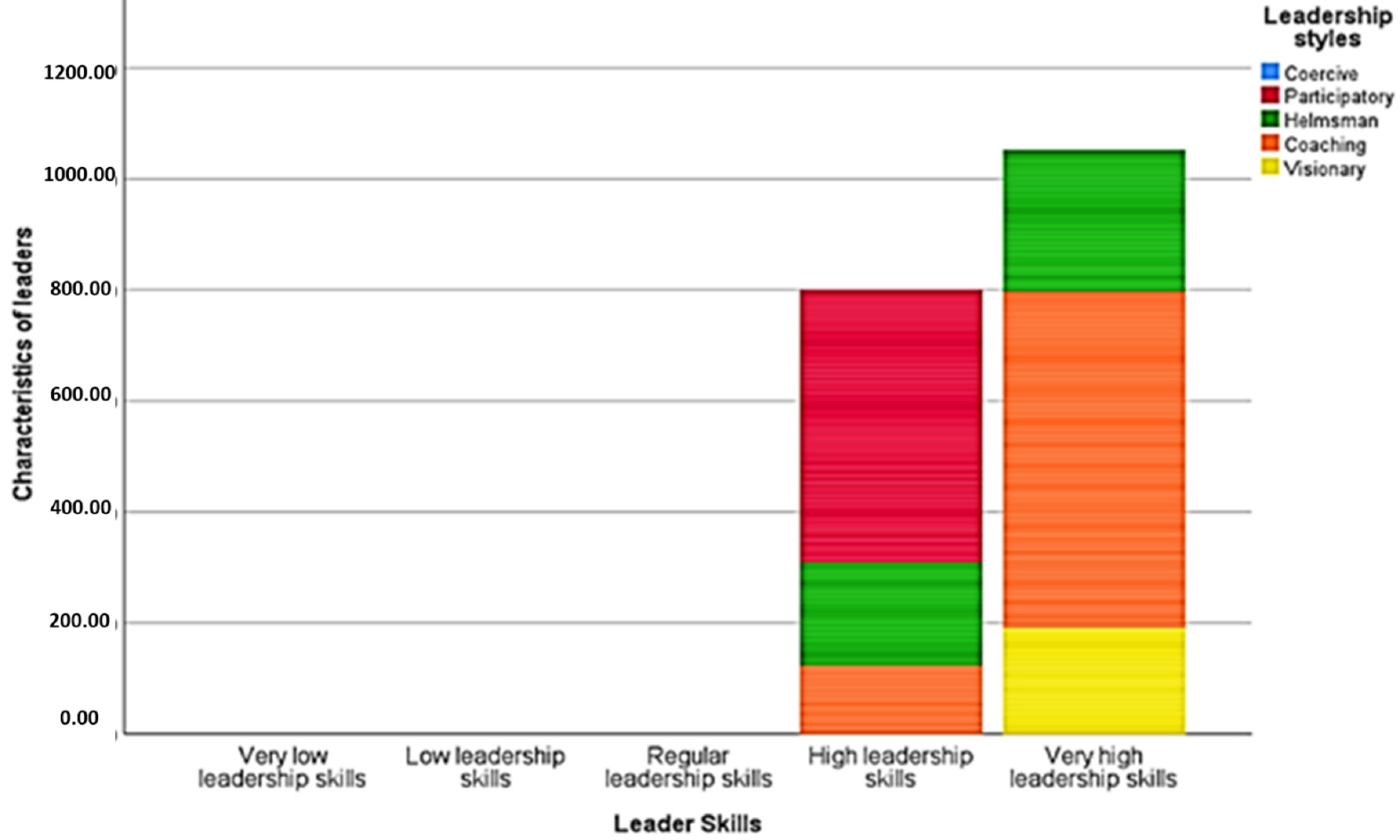

| Dimension: Leadership Styles | |

| Min–1.80 | Coercive |

| 1.81–2.60 | Participatory |

| 2.61–3.40 | Helmsman |

| 3.41–4.20 | Coaching |

| 4.21–Max | Visionary |

| Dimension: Leadership Skills | |

| Min–1.80 | Deficient leadership skills. |

| 1.81–2.60 | Low leadership skills. |

| 2.61–3.40 | Regular leadership skills. |

| 3.41–4.20 | High leadership skills. |

| Women’s Leadership | Characteristics of Leaders | Leadership Styles | Leader Skills | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High presence of N female leadership | Valid | 179 | 179 | 179 |

| Lost | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mean | 5.00 | 2.58 | 4.07 | |

| Median | 5.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | |

| Mode | 5 | 2 | 4 | |

| Deviation | 0.000 | 0.733 | 0.260 | |

| Variance | 0.000 | 0.538 | 0.068 | |

| Very high presence of female leadership. | Valid | 204 | 204 | 204 |

| Lost | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mean | 5.00 | 4.00 | 5.00 | |

| Median | 5.00 | 4.00 | 5.00 | |

| Mode | 5 | 4 | 5 | |

| Deviation | 0.000 | 0.620 | 0.000 | |

| Variance | 0.000 | 0.384 | 0.000 | |

| Minimum | 5 | 3 | 5 | |

| Maximum | 5 | 5 | 5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Gonzalez-Diaz, R.; Vargas, E.C.; Paz-Marcano, A.; Muller-Pérez, S.; Salazar-Sepúlveda, G.; Caruso, G.; D’Adamo, I. Resilience, Leadership and Female Entrepreneurship within the Context of SMEs: Evidence from Latin America. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8129. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158129

Acevedo-Duque Á, Gonzalez-Diaz R, Vargas EC, Paz-Marcano A, Muller-Pérez S, Salazar-Sepúlveda G, Caruso G, D’Adamo I. Resilience, Leadership and Female Entrepreneurship within the Context of SMEs: Evidence from Latin America. Sustainability. 2021; 13(15):8129. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158129

Chicago/Turabian StyleAcevedo-Duque, Ángel, Romel Gonzalez-Diaz, Elena Cachicatari Vargas, Anherys Paz-Marcano, Sheyla Muller-Pérez, Guido Salazar-Sepúlveda, Giulia Caruso, and Idiano D’Adamo. 2021. "Resilience, Leadership and Female Entrepreneurship within the Context of SMEs: Evidence from Latin America" Sustainability 13, no. 15: 8129. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158129

APA StyleAcevedo-Duque, Á., Gonzalez-Diaz, R., Vargas, E. C., Paz-Marcano, A., Muller-Pérez, S., Salazar-Sepúlveda, G., Caruso, G., & D’Adamo, I. (2021). Resilience, Leadership and Female Entrepreneurship within the Context of SMEs: Evidence from Latin America. Sustainability, 13(15), 8129. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158129