Social Media Use of Small Wineries in Alsace: Resources and Motivations Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Importance of Social Media Usage

2.2. Social Media Usage in the Wine Industry

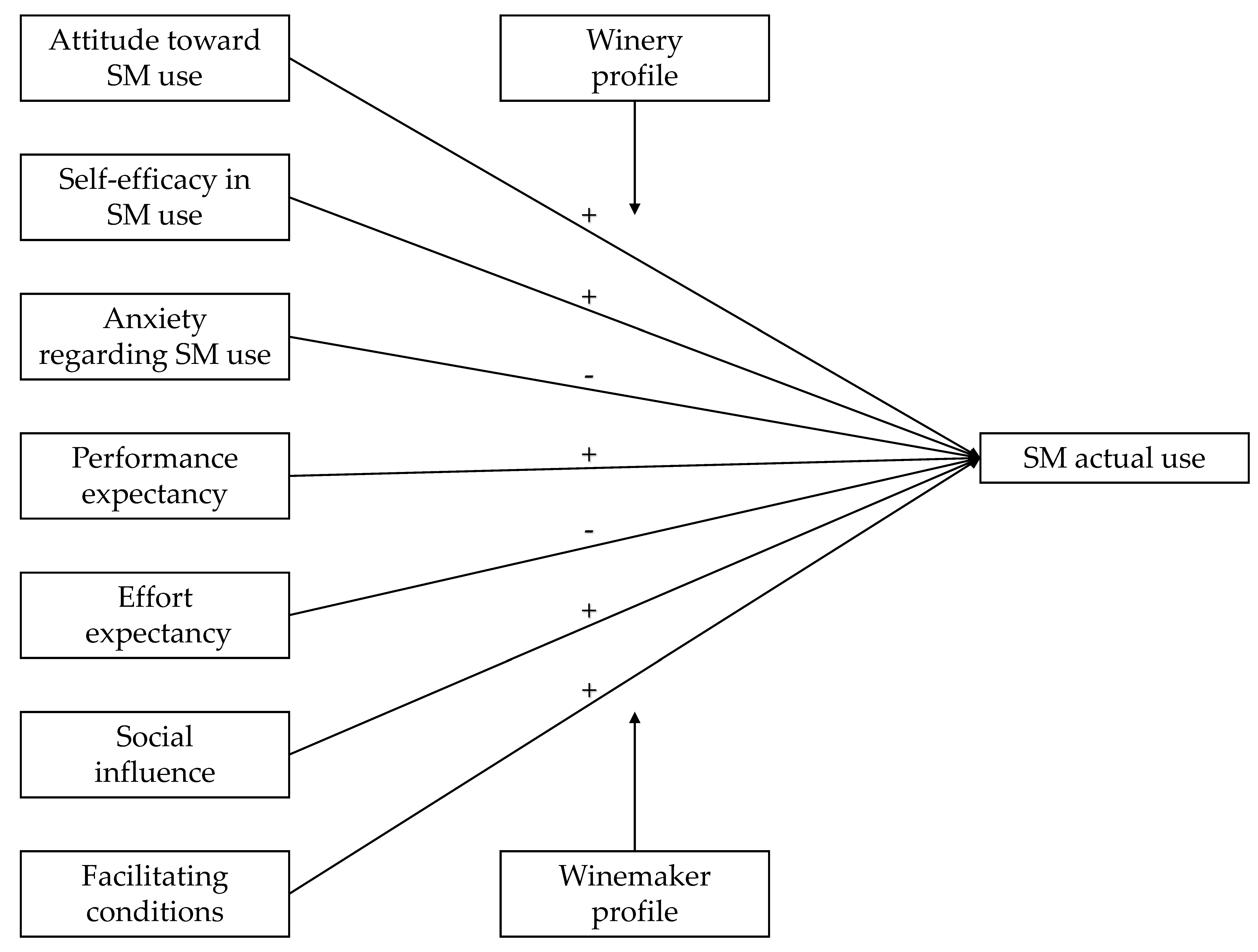

2.3. Predictors of Social Media Use

3. Methodology

3.1. Context of Study

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Descriptive Statistics

4. Results

4.1. Current Social Media Usage of Wineries

4.2. Differences in Use According to the Profiles of Wineries and Winemakers

4.3. Strategic Objectives Related to Wineries’ Social Media Use

4.4. Factors Contributing to Social Media Usage

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Babić Rosario, A.; de Valck, K.; Sotgiu, F. Conceptualizing the electronic word-of-mouth process: What we know and need to know about EWOM creation, exposure, and evaluation. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 422–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S. Information search in the internet markets: Experience versus search goods. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2018, 30, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo-Thanh, T.; Kirova, V. Wine tourism experience: A netnography Study. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 83, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szolnoki, G.; Dolan, R.; Forbes, S.; Thach, L.; Goodman, S. Using social media for consumer interaction: An international comparison of winery adoption and activity. Wine Econ. Policy 2018, 7, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storchmann, K. Wine economics. J. Wine Econ. 2012, 7, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Richter, B.; Hanf, J.H. Cooperatives in the wine industry: Sustainable management practices and digitalisation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, C.; Thach, L.; Olsen, J. Understanding eWinetourism practices of European and North America wineries. J. Gastron. Tour. 2020, 4, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargain, O. French wine exports to China: Evidence from intra-French regional diversification and competition. J. Wine Econ. 2020, 15, 134–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szolnoki, G.; Thach, L.; Kolb, D. Current status of global wine ecommerce and social media. In Successful Social Media and Ecommerce Strategies in the Wine Industry; Szolnoki, G., Thach, L., Kolb, D., Eds.; Palgrave Pivot: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-137-60297-8. [Google Scholar]

- Szolnoki, G.; Taits, D.; Nagel, M.; Fortunato, A. Using social media in the wine business: An exploratory study from Germany. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2014, 26, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogari, G.; Pucci, T.; Aquilani, B.; Zanni, L. Millennial generation and environmental sustainability: The role of social media in the consumer purchasing behavior for wine. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Madill, J.; Neilson, L.C. Web site utilization in SME business strategy: The case of Canadian wine SMEs. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2010, 23, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neilson, L.; Madill, J. Using winery web sites to attract wine tourists: An international comparison. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2014, 26, 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristófol, F.J.; Aramendia, G.Z.; de-San-Eugenio-Vela, J. Effects of social media on enotourism. Two cases study: Okanagan Valley (Canada) and Somontano (Spain). Sustainability 2020, 12, 6705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilipour, A. Introduction to social sustainability. In Social Sustainability in the Global Wine Industry: Concepts and Cases; Forbes, S.L., De Silva, T.-A., Gilinsky, A., Eds.; Palgrave Pivot: London, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-30412-6. [Google Scholar]

- Zucca, G.; Smith, D.; Mitry, D.J. Sustainable viticulture and winery practices in California: What is it, and do customers care? Int. J. Wine Res. 2009, 1, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sellers-Rubio, R.; Nicolau-Gonzalbez, J.L. Estimating the willingness to pay for a sustainable wine using a Heckit model. Wine Econ. Policy 2016, 5, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilinsky, A. Introduction. In Crafting Sustainable Wine Businesses: Concepts and Cases; Gilinsky, A., Ed.; Palgrave Pivot: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-137-55306-5. [Google Scholar]

- Staub, C.; Michel, F.; Bucher, T.; Siegrist, M. How do you perceive this wine? Comparing naturalness perceptions of Swiss and Australian consumers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 79, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maykish, A.; Rex, R.; Sikalidis, A.K. Organic winemaking and its subsets: Biodynamic, natural, and clean wine in California. Foods 2021, 10, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sogari, G.; Corbo, C.; Macconi, M.; Menozzi, D.; Mora, C. Consumer attitude towards sustainable-labelled wine: An exploratory approach. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2015, 27, 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, S.L.; De Silva, T.-A. Analysis of environmental management systems in New Zealand wineries. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2012, 24, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dressler, M.; Haller, C. Does culture show in philanthropic engagement? An empirical exploration of German and French wineries. In Social Sustainability in the Global Wine Industry: Concepts and Cases; Forbes, S.L., De Silva, T.-A., Gilinsky, A., Eds.; Palgrave Pivot: London, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-30412-6. [Google Scholar]

- Michel-Villarreal, R.; Vilalta-Perdomo, E.L.; Canavari, M.; Hingley, M. Resilience and digitalization in short food supply chains: A case study approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo-Thanh, T.; Zaman, M.; Hasan, R.; Rather, R.A.; Lombardi, R.; Secundo, G. How a mobile app can become a catalyst for sustainable social business: The case of too good to go. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 171, 120962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bitiktas, F.; Tuna, O. Social media usage in container shipping companies: Analysis of Facebook messages. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2020, 34, 100454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-L.; Chang, C.-Y. Understanding how people select social networking services: Media trait, social influences and situational factors. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinets, R.V.; de Valck, K.; Wojnicki, A.C.; Wilner, S.J.S. Networked narratives: Understanding word-of-mouth marketing in online communities. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Liu, H.; Huang, Q.; Gu, J. Enterprise social networking usage as a moderator of the relationship between work stressors and employee creativity: A multilevel study. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 103165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Bakici, T. Enterprise social media usage: The motives and the moderating role of public social media experience. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 101, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leftheriotis, I.; Giannakos, M.N. Using social media for work: Losing your time or improving your work? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakara, W.A.; Benmoussa, F.Z.; Jaouen, A. Entrepreneurship and social media marketing: Evidence from French small business. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2012, 16, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, M. Direct selling in the wine sector: Lessons from cellars in Italy’s Apulia region. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 1946–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, A.; Crescimanno, M.; Tinervia, S.; Fagnani, F. Social media as a strategic marketing tool in the Sicilian wine industry: Evidence from Facebook. Wine Econ. Policy 2017, 6, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukovic, D.B.; Maiti, M.; Vujko, A.; Shams, R. Residents’ perceptions of wine tourism on the rural destinations development. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 2739–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez Vicente, G.; Martín Barroso, V.; Blanco Jiménez, F.J. Sustainable tourism, economic growth and employment—The case of the wine routes of Spain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, N.A. Digital wine marketing: Social media marketing for the wine industry. BIO Web Conf. 2016, 7, 03011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Del Mastio, A.; Caldelli, R.; Casini, M.; Manetti, M. SMARTVINO Project: When wine can benefit from ICT. Wine Econ. Policy 2016, 5, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, C.; Szolnoki, G.; Thach, L. Cross-cultural comparison of social media usage in the wine industry: Differences between the United States and Germany. In Successful Social Media and Ecommerce Strategies in the Wine Industry; Szolnoki, G., Thach, L., Kolb, D., Eds.; Palgrave Pivot: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 9781349888139. [Google Scholar]

- Velikova, N.; Wilcox, J.B.; Dodd, T.H. Designing effective winery websites: Marketing oriented versus wine-oriented websites. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference of the Academy of Wine Business Research, Bordeaux Management School, Bordeaux, France, 9–10 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Thach, L.; Lease, T.; Barton, M. Exploring the impact of social media practices on wine sales in US Wineries. J. Direct Data Digit. Mark. Pract. 2016, 17, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mick, H. Direct to consumer: Growing wine sales by strengthening online engagement with customers. Aust. N. Z. Grapegrow. Winemak. 2020, 78–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minolta, K. A Toast to the Digital Transformation of the Renewed Winegrowing Industry. Available online: https://www.konicaminolta.eu/eu-en/rethink-work/business/a-toast-to-the-digital-transformation-of-the-renewed-winegrowing-industry (accessed on 11 July 2021).

- Costopoulou, C.; Ntaliani, M.; Ntalianis, F. An analysis of social media usage in winery businesses. Adv. Sci. Technol. Eng. Syst. J. 2019, 4, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garcia, M. French wine industry digitalisation: Issues, innovations, and trends. In Proceedings of the 63rd International DWV-Congress, Stuttgart, Germany, 4–6 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Iaia, L.; Scorrano, P.; Fait, M.; Cavallo, F. Wine, family businesses and web: Marketing strategies to compete effectively. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 2294–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, T.A.; Siegrist, M. Lifestyle determinants of wine consumption and spending on wine. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2011, 23, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqueveque, C.; Rodrigo, P. “This Wine Is Dead!”: Unravelling the effect of word-of-mouth and its moderators in price-based wine quality perceptions. Br. Food J. 2020, 123, 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucci, T.; Casprini, E.; Nosi, C.; Zanni, L. Does social media usage affect online purchasing intention for wine? The moderating role of subjective and objective knowledge. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, L.; Mills, A.; Chan, A.; Menguc, B.; Plangger, K. Using chernoff faces to portray social media wine brand images. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference of the Academy of Wine Business Research, Bordeaux Management School, Bordeaux, France, 9–10 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Quinton, S.; Harridge-March, S. Relationships in online communities: The potential for marketers. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2010, 4, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capitello, R.; Agnoli, L.; Begalli, D.; Codurri, S. Social media strategies and corporate brand visibility in the wine industry: Lessons from an Italian case study. EuroMed. J. Bus. 2014, 9, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beninger, S.; Parent, M.; Pitt, L.; Chan, A. A content analysis of influential wine blogs. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2014, 26, 168–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2020 Wine Production. OIV First Estimates; International Organisation of Vine and Wine: Paris, France, 2020.

- Haller, C.; Plotkina, D. Analysis of user-experience evaluation of French winery websites. In Handbook of Research on User Experience in Web 2.0 Technologies and Its Impact on Universities and Businesses; Pelet, J.-E., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; ISBN 9781799837565. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.; Morris, M. Dead or alive? The development, trajectory and future of technology adoption research. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2007, 8, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamilmani, K.; Rana, N.P.; Wamba, S.F.; Dwivedi, R. The extended unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT2): A systematic literature review and theory evaluation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 57, 102269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.; Xu, X. Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology: A synthesis and the road ahead. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2016, 17, 328–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Rodríguez, T.; Carvajal-Trujillo, E. Online purchasing tickets for low cost carriers: An application of the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) model. Tour. Manag. 2014, 43, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, B. An application of UTAUT model for acceptance of social media in Egypt: A statistical study. Int. J. Inf. Sci. 2012, 2, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, D.; McQueen, R.J. Extending UTAUT to explain social media adoption by microbusinesses. Int. J. Manag. Inf. Technol. 2012, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruzd, A.; Staves, K.; Wilk, A. Connected scholars: Examining the role of social media in research practices of faculty using the UTAUT model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 2340–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y. What a smartphone is to me: Understanding user values in using smartphones. Inf. Syst. J. 2014, 24, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirova, V.; Vo-Thanh, T. Smartphone use during the leisure theme park visit experience: The role of contextual factors. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 742–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key Figures. Available online: https://www.fevs.com/en/the-sector/key-figures/ (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Chiffres Clés. Available online: https://www.vinetsociete.fr/chiffres-cles (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Haller, C.; Plotkina, D.; Fabing, E. Œnotourisme: Le Virtuel Comme Levier de Développement? Available online: https://www.forbes.fr/business/oenotourisme-le-virtuel-comme-levier-de-developpement/ (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Fuentes Fernández, R.; Vriesekoop, F.; Urbano, B. Social media as a means to access millennial wine consumers. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2017, 29, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SOWINE Les Français et le Vin. Available online: https://sowine.com/barometre/barometre-2021/page-1-2/ (accessed on 11 July 2021).

- Kemp, S. Digital 2020: France. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-france (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. An overview of psychological measurement. In Clinical Diagnosis of Mental Disorders: A Handbook; Wolman, B.B., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1978; ISBN 9781468424904. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2014; ISBN 9781292021904. [Google Scholar]

- Newberry, C. 44 Instagram Statistics that Matter to Marketers in 2021. Social Media Marketing & Management Dashboard. 2021. Available online: https://blog.hootsuite.com/instagram-statistics/ (accessed on 11 July 2021).

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 9781452242569. [Google Scholar]

| Mean (Standard Deviation) | Never (Percentage) | Rarely (Percentage) | Often (Percentage) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.92 (2.12) | 13 (16.7%) | 22 (28.2%) | 43 (55.1%) | |

| 3.60 (2.31) | 28 (35.9%) | 31 (39.7%) | 19 (24.4%) | |

| 2.31 (1.92) | 48 (61.5%) | 23 (29.5%) | 7 (9%) | |

| YouTube | 2.24 (1.68) | 43 (55%) | 30 (38.5%) | 5 (6.5%) |

| Blog | 2.23 (1.70) | 45 (57.7%) | 29 (37.2%) | 4 (5.1%) |

| Professional wine-related SM | 2.10 (1.52) | 27 (34.6%) | 32 (41%) | 19 (24.4%) |

| 2.05 (1.41) | 45 (57.7%) | 25 (32%) | 8 (10.3%) | |

| SM use | 2.64 (1.18) | 11 (14.1%) | 59 (75.6%) | 8 (10.3%) |

| Total | Min 1 Max 7 | 78 (100%) | ||

| Winery Age | Size | Export Orientation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Recently founded (from 1971 to 2020) | Historical (from 1620 to 1970) | Less than 5 employees | From 5 to 50 employees | Part of production exported from 0% to 90% (median 17%) |

| N | 35 | 43 | 59 | 19 | - |

| Mean (Standard Deviation) | Standardised coefficient of linear regression | ||||

| 4.96 (2.21) | 4.67 (2.14) | 4.54 (2.17) | 5.79 (1.76) | 0.354 *** | |

| 3.81 (2.45) | 3.48 (2.42) | 3.11 (2.23) | 4.71 (2.13) | 0.245 * | |

| 2.52 (2.15) | 2.50 (2.08) | 1.87 (1.59) | 3.29 (2.25) | 0.392 *** | |

| YouTube | 2.37 (1.77) | 2.08 (1.62) | 1.91 (1.45) | 3.00 (1.93) | 0.058 |

| Blog | 2.19 (1.74) | 2.37 (1.86) | 1.91 (1.54) | 2.96 (1.89) | 0.203 |

| Professional wine-related SM | 2.27 (1.55) | 2.26 (1.73) | 2.02 (1.46) | 2.29 (1.68) | −0.094 |

| 2.37 (1.57) | 2.08 (1.46) | 1.81 (1.33) | 2.58 (1.47) | 0.127 | |

| Winemaker Age | Winemaker Education | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | 20–39 | 40–54 | 55–73 | Commercial/managerial | Wine-making technics |

| N | 18 | 35 | 25 | 37 | 41 |

| Mean (Standard Deviation) | |||||

| 5.44 (2.06) | 4.41 (2.30) | 5.42 (1.76) | 5.42 (1.85) | 4.78 (2.19) | |

| 4.06 (2.67) | 3.14 (2.32) | 4.00 (2.04) | 4.58 (2.19) | 2.90 (2.23) | |

| 2.81 (2.37) | 1.84 (1.69) | 2.63 (1.86) | 3.00 (2.19) | 1.83 (1.71) | |

| YouTube | 2.63 (1.89) | 2.05 (1.66) | 2.21 (1.58) | 2.65 (1.74) | 1.93 (1.57) |

| Blog | 2.69 (1.95) | 1.89 (1.64) | 2.38 (1.63) | 2.77 (1.81) | 2.00 (1.65) |

| Professional wine-related SM | 2.38 (1.78) | 2.00 (1.45) | 2.00 (1.47) | 2.19 (1.55) | 2.10 (1.51) |

| 1.94 (1.48) | 1.65 (1.16) | 2.67 (1.52) | 2.31 (1.46) | 1.68 (1.15) | |

| Strategic Objectives/SM Use | Commercial Transactions | Promotional Offers | Information about Winery’s Activities (Viticultural, Wine-Making, etc.) | Wine Tourism (Visiting the Winery and Tasting) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total: Mean (Std. Dev.) | 3.29 (1.97) | 4.75 (2.19) | 4.88 (2.16) | 4.43 (2.13) |

| 0.426 *** | 0.722 *** | 0.819 *** | 0.628 *** | |

| 0.437 *** | 0.610 *** | 0.605 *** | 0.381 *** | |

| 0.443 *** | 0.361 *** | 0.372 *** | 0.052 | |

| YouTube | 0.113 | 0.224 | 0.250 * | 0.233 * |

| Blog | 0.390 *** | 0.230 * | 0.271 * | 0.197 |

| Professional wine-related SM | 0.248 * | 0.042 | 0.071 | 0.189 |

| 0.274 * | 0.217 | 0.263 * | 0.256 * | |

| SM use (total) | 0.523 *** | 0.567 *** | 0.619 *** | 0.437 *** |

| Scale | Mean (Std. Dev.) | Factor Loading | Alpha Cro. | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude toward SM use | 0.887 | 0.922 | 0.748 | ||

| 1. Using SM is a good idea. | 4.92 (1.56) | 0.758 | |||

| 2. SM makes work more interesting. | 3.82 (1.81) | 0.887 | |||

| 3. Working with the SM is fun. | 3.76 (1.88) | 0.925 | |||

| 4. I like working with the SM. | 3.98 (1.72) | 0.881 | |||

| Self-efficacy in SM use (R) | 0.875 | 0.915 | 0.731 | ||

| I could complete a job or task using SM ... | |||||

| 1. If there is someone around to tell me what to do as I go. | 3.68 (2.01) | 0.859 | |||

| 2. If I could call someone for help if I got stuck. | 4.09 (1.90) | 0.89 | |||

| 3. If I had a lot of time to complete the job for which the software was provided. | 4.26 (2.06) | 0.784 | |||

| 4. If I had just the built-in help facility for assistance. | 3.94 (1.83) | 0.884 | |||

| Anxiety regarding SM use | 0.919 | 0.943 | 0.807 | ||

| 1. I feel apprehensive about using SM. | 2.70 (1.65) | 0.845 | |||

| 2. It scares me to think that I could lose a lot of information using SM by hitting the wrong key. | 2.54 (1.66) | 0.934 | |||

| 3. I hesitate to use SM for fear of making mistakes I cannot correct. | 2.39 (1.58) | 0.954 | |||

| 4. SM is somewhat intimidating to me. | 2.28 (1.50) | 0.856 | |||

| Performance expectancy | 0.784 | 0.724 | 0.419 | ||

| 1. I would find SM useful in my job. | 4.81 (1.70) | 0.834 | |||

| 2. Using SM enables me to accomplish tasks more quickly. | 4.04 (1.86) | 0.864 | |||

| 3. Using SM increases my productivity. | 3.50 (1.77) | 0.865 | |||

| 4. If I use SM, I will increase my chances of getting a raise. | 4.05 (1.70) | 0.532 | |||

| Effort expectancy | 0.956 | 0.967 | 0.883 | ||

| 1. My interaction with SM would be clear and understandable. | 4.04 (1.60) | 0.907 | |||

| 2. It would be easy for me to become skillful at using SM. | 4.15 (1.76) | 0.951 | |||

| 3. I would find SM easy to use. | 3.99 (1.73) | 0.949 | |||

| 4. Learning to operate SM is easy for me. | 4.03 (1.79) | 0.951 | |||

| Social influence¤ | 0.769 | 0.868 | 0.691 | ||

| 1. People who influence my behaviour think that I should use SM. | 3.88 (1.64) | 0.905 | |||

| 2. People who are important to me think that I should use SM. | 3.88 (1.71) | 0.893 | |||

| 3. In general, the organisation has supported the use of SM | 4.46 (1.68) | 0.677 | |||

| Facilitating conditions | 0.836 | 0.891 | 0.672 | ||

| 1. I have the resources necessary to use SM. | 3.49 (1.80) | 0.750 | |||

| 2. I have the knowledge necessary to use SM. | 4.17 (1.71) | 0.860 | |||

| 3. SM is compatible with other SM I use. | 4.03 (1.74) | 0.832 | |||

| 4. A specific person (or group) is available for assistance with SM difficulties. | 3.91 (1.92) | 0.835 |

| Explanatory Factor | Coefficient of Impact on SM Use (Standard Error) |

|---|---|

| Attitude toward SM use | 0.185 (0.015) |

| Self-efficacy in SM use | 0.138 (0.077) * |

| Anxiety regarding SM use | −0.098 (0.095) |

| Performance expectancy | −0.011 (0.104) |

| Effort expectancy | −0.064 (0.168) |

| Social influence | −0.082 (0.104) |

| Facilitating conditions | 0.492 (0.131) *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haller, C.; Plotkina, D.; Vo-Thanh, T. Social Media Use of Small Wineries in Alsace: Resources and Motivations Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158149

Haller C, Plotkina D, Vo-Thanh T. Social Media Use of Small Wineries in Alsace: Resources and Motivations Analysis. Sustainability. 2021; 13(15):8149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158149

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaller, Coralie, Daria Plotkina, and Tan Vo-Thanh. 2021. "Social Media Use of Small Wineries in Alsace: Resources and Motivations Analysis" Sustainability 13, no. 15: 8149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158149

APA StyleHaller, C., Plotkina, D., & Vo-Thanh, T. (2021). Social Media Use of Small Wineries in Alsace: Resources and Motivations Analysis. Sustainability, 13(15), 8149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158149