Potential of Marketing Communication as a Sustainability Tool in the Context of Castle Museums

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Backround

- advertisement to promote the institution, its name, and image;

- advertisement to promote the product, means exhibition;

- advertisement to promote a one-time event or social occasion;

- advertisement aimed at raising the awareness of visitors, for example, by museum club membership [66].

3. Materials and Methods

- registration in the Central List of Cultural Heritage of the Slovak Republic;

- offering of services for the general public throughout the year;

- a part of Slovak history and national identity;

- receive regular transfers commonly known as internal or foreign grants for their activities and development;

- have more than 1000 expert-registered museum items;

- in the terms of human resources, they recruit on permanent employment and work agreements;

- core museum product is created permanent exhibition (sightseeing tour)

- exhibitions are available only with the supervision of the museum guide (lecturer) who provides interpretative services to museum customers. Audio guides might be used for additional customer communication activities;

- provision of a wide scale of cultural, educational, and recreational activities;

- communication with the public conducted via websites, social media, media reports, conferences, open days, etc.

What was the purpose of your visit?How many times have you visited this castle museum?Will you visit this museum in the future?What were the information sources and how did you learn about the museum?How do you rate the museum’s website?How do you rate the museum’s communication via social media?

- Vo1: Is there a dependency between the quality of offline marketing communication activities and the intention of customers to visit the castle museum repeatedly?

- Vo2: Is there a dependency between the events organization and the intention of customers to visit the castle museum repeatedly?

Data Analysis

4. Results

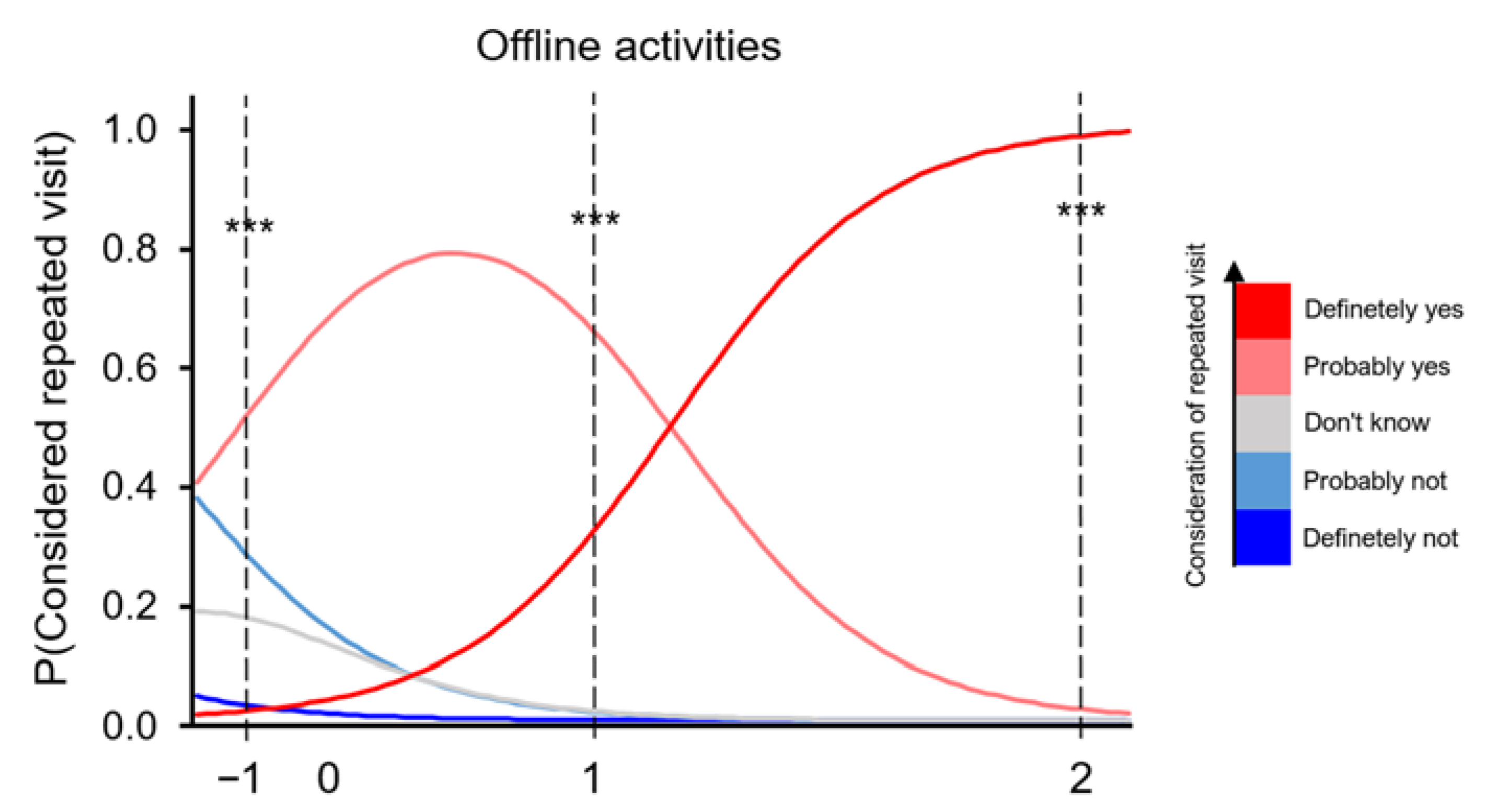

4.1. Effect of Evaluated Quality of Offline Activities on Consideration of the Repeated Visit

4.2. SEffect of Visit Intention on Consideration of Repeated Visits

5. Discussion

- -

- The robust effect of evaluating quality of offline activities on consideration to repeatedly visit an object, χ2(3) = 4417.6, p < 0.001);

- -

- intent of a visit had statistically significant effect on the consideration to repeatedly visit an object, χ2(3) = 725.8, p < 0.001),

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Glaser-Segura, D.; Nistoreanu, P.; Dincă, V.M. Considerations on Becoming a World Heritage Site—A Quantitative Approach. Amfiteatru Econ. 2018, 20, 202–216. [Google Scholar]

- Vo, N.; Chovancová, M.; Tri, H.T. A major boost to the website performance of up-scale hotels in Vietnam. Manag. Mark. Chall. Knowl. Soc. 2019, 14, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UNESCO. Fribourg Declaration on Cultural Rights; Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie: Geneva, Switzerland; University of Fribourg: Geveva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L. The reform and practical exploration of Chinese tourism culture curriculum. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Humanities Science and Society Development (ICHSSD 2017), Xiamen, China, 18–19 November 2017; Atlantis Press: Zhengzhou, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, H. A Study on the Development of Jilin Shaman Culture Tourism Products. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium on Social Science (ISSS 2017), Dalian, China, 13–14 May 2017; Atlantis Press: Zhengzhou, China, 2017; pp. 405–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robinson, D. Rural Wine and Food Tourism for Cultural Sustainability. Tour. Anal. 2021, 26, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slušná, Z. Súčasná Kultúrna Situácia z Pohľadu Teórie a Praxe; Univerzita Komenského v Bratislave: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2015; p. 118. ISBN 978-80-223-4026-7. [Google Scholar]

- Volkova, E. Digitizing Galicia: Cultural Policies and Trends in Cultural Heritage Management. Abriu Estud. Textualidade Bras. Galicia Port. 2019, 7, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throsby, D. The Economics of Cultural Policy; Cambridge University Press (CUP): New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Craik, J. Re-Visioning Arts and Cultural Policy: Current Impasses and Future Directions; ANU E Press: Canberra, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hidle, K.; Leknes, E. Policy Strategies for New Regionalism: Different Spatial Logics for Cultural and Business Policies in Norwegian City Regions. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 22, 126–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotamaa, O.; Jørgensen, K.; Sandqvist, U. Public game funding in the Nordic region. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2020, 26, 617–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patočka, J.; Heřmanová, E. Lokální a Regionální Kultura v České Republice; ASPI: Praha, Czech Republic, 2008; p. 199. ISBN 978-80-7357-347-8. [Google Scholar]

- Pauliukevičiūtė, A.; Raipa, A. Culture management key challenges in changing economic environment. In Proceedings of the 7th International Scientific Conference “Business and Management”, Vilnius, Lithuania, 10–11 May 2012; pp. 701–708. [Google Scholar]

- Pauliukevičiūtė, A.; Jucevičius, R. Six smartness dimensions in cultural management: Social/cultural environment perspective. Bus. Manag. Educ. 2018, 16, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson, N. Simply Complexity: A Clear Guide to Complexity Theory; Simon and Schuster: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Alperytė, I. Managing Cultural Differences in Business: Identity vs. Otherness; Global Business Management, Selected Papers; University of Applied Sciences Upper Austria: Vienna, Austria, 2010; pp. 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bučinskas, A.; Raipa, A.; Pauliukevičiūtė, A. Modern aspects of implementation of cultural policy. Bridges 2010, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cray, D.; Inglis, L. Strategic Decision Making in Arts Organizations. J. Arts Manag. Law Soc. 2011, 41, 84–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, P. Transnational Cultural Policymaking in the European Union. J. Arts Manag. Law Soc. 2008, 38, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesmondhalgh, D.; Pratt, A. Cultural industries and cultural policy. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2005, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chong, D. Arts Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; p. 264. ISBN 9781135263362. [Google Scholar]

- Blštáková, J.; Joniaková, Z.; Skorková, Z.; Némethová, I.; Bednár, R. Causes and Implications of the Applications of the Individualisation Principle in Human Resources Management. AD ALTA J. Interdiscip. Res. 2019, 9, 323–327. [Google Scholar]

- Sirkova, M.; Taha, V.A.; Ferencova, M. Management of HR processes in the specific contexts of selected area. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 13, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitka, M.; Závadská, Z.; Jelačić, D.; Balážová, Ž. Qualitative Indicators of Company Employee Satisfaction and Their Development in a Particular Period of Time. Drv. Ind. 2015, 66, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michalski, G.; Blendinger, G.; Rozsa, Z.; Cierniak-Emerych, A.; Svidronova, M.; Buleca, J.; Bulsara, H. Can we determine debt to equity levels in non-profit organisations? Answer based on Polish case. Eng. Econ./Inžinerinė Ekon. 2018, 29, 526–535. [Google Scholar]

- Jureniene, V.; Radzevicius, M. Models of Cultural Heritage Management. In Transformations in Business and Economics; Vilnius University: Kaunas, Lithuania, 2014; Volume 13, pp. 236–256. [Google Scholar]

- Scapolan, A.; Montanari, F.; Bonesso, S.; Gerli, F.; Mizzau, L. Behavioural competencies and organizational performance in Italian performing arts: An exploratory study. Acad. Rev. Latinoam. Adm. 2017, 30, 192–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandel, B.R.; Lambert, P.D. International Arts/Cultural Management: Global Perspectives on Strategies, Competencies, and Education. J. Arts Manag. Law Soc. 2020, 50, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetráková, M.; Smerek, L. Competitiveness of Slovak enterprises in Central and Eastern European region. E+M Èkon. Manag. 2019, 22, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raišienė, A.G. Business and management success: What course is supported by sustainable organization managers. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2015, 14, 68–91. [Google Scholar]

- Nechita, F. The New Concepts Shaping the Marketing Communication Strategies of Museums; Bulletin of The Transilvania University of Brasov: Brasov, Romania, 2014; pp. 269–278. [Google Scholar]

- Podušelová, G. Na úvod. In Zborník Príspevkov zo Seminára Múzeum v Spoločnosti; SNM-Národné Múzejné Centrum: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2002; ISBN 978-80-8060-097-X. [Google Scholar]

- Diker, M.; Erkan, N. Building for the City Identity: The Case of Antioch. Plan. Plan. 2017, 27, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gorlova, I.I.; Bychkova, O.I.; Kostina, N.A. Museum Sphere as a Source of Ethnocultural Branding: Methodical Aspects of Evaluation. Vestnik Tomskogo Gosudarstvennogo Universiteta-Kulturologiya I Iskusstvovedenie-Tomsk State University. J. Cult. Stud. Art Hist. 2019, 36, 222–231. [Google Scholar]

- Baltas, G. An applied analysis of brand demand structure. Appl. Econ. 2002, 34, 1171–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; McCabe, S. Sustainability and marketing in tourism: Its contexts, paradoxes, approaches, challenges and potential. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Escobar-Sierra, M.; García-Cardona, A.; Acevedo, L.D.V. How moral outrage affects consumer’s perceived values of socially irresponsible companies. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1888668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, E.; Wall, G. Marketing Tourism Destinations: A Strategic Planning Approach; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, A.M. Marketing and Managing Tourism Destinations; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bratić, D.; Palić, M.; Tomašević Lišanin, M.; Gajdek, D. Green marketing communications in the function of sustainable development. In Proceedings of the 11th Annual Conference of the EuroMed Academy of Business: Research Advancements in National and Global Business Theory and Practice, Valletta, Malta, 12–14 September 2018; p. 185. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, I.C.; Dumitru, I.; Vegheş, C.; Kailani, C. Marketing communication as a vector of the Romanian small businesses sustainable development. Amfiteatru Econ. 2013, 15, 671–686. [Google Scholar]

- Schüller, D.; Doubravský, K. Fuzzy similarity used by micro-enterprises in marketing communication for sustainable development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kopytko, O.; Lagodiienko, V.; Falovych, V.; Tchon, L.; Dovhun, O.; Litvynenko, M. Marketing communications as a factor of sustainable development. Int. J. Eng. Adv. Technol. 2019, 8, 3305–3309. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.K. When Arts Met Marketing: Arts Marketing Theory Embedded in Romanticism. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2005, 11, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.W.; Lee, S.H. “Marketing from the Art World”: A Critical Review of American Research in Arts Marketing. J. Arts Manag. Law Soc. 2017, 47, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boorsma, M.; Chiaravalloti, F. Arts Marketing Performance: An Artistic-Mission-Led Approach to Evaluation. J. Arts Manag. Law Soc. 2010, 40, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupec, V.; Lukáč, M.; Štarchoň, P.; Bartáková, G.P. Audit of Museum Marketing Communication in the Modern Management Context. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2020, 8, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okolnishnikova, I.Y.; Greyz, G.M.; Kuzmenko, Y.G.; Katochkov, V.M. Formation and development of marketing communications in the context of consumer demand individualization. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Business Information Management Association Conference, IBIMA 2018-Vision 2020: Sustainable Economic Development and Application of Innovation Management from Regional Expansion to Global Growth, Seville, Spain, 15–16 November 2018; pp. 7401–7406. [Google Scholar]

- Štarchoň, P.; Vetráková, M.; Metke, J.; Lorincová, S.; Hitka, M.; Weberová, D. Introduction of a New Mobile Player App Store in Selected Countries of Southeast Asia. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zollo, L.; Rialti, R.; Marrucci, A.; Ciappei, C. How do museums foster loyalty in tech-savvy visitors? The role of social media and digital experience. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprilia, F.; Kusumawati, A. Influence of Electronic Word of Mouth on Visitor’s Interest to Tourism Destinations. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 993–1003. [Google Scholar]

- Fedorov, M.V.; Starovoitova, Y.Y. Enhancing Planning Techniques in the Restaurant Marketing. Upravlenets (Manag.) 2011, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Girchenko, T.D.; Panchenko, O.V. Research on the Practical Aspects of the Providing Efficiency of Marketing Communications’ Bank. Financ. Credit. Act. Probl. Theory Pract. 2020, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, K.; Mantrala, M.; Sridhar, S.; Tang, Y. (Elina) Optimal Resource Allocation with Time-varying Marketing Effectiveness, Margins and Costs. J. Interact. Mark. 2012, 26, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojtech, F.; Levický, M.; Filip, S. Economic policy for sustainable regional development: A case study of Slovak Republic. J. Secur. Sustain. Issues 2019, 8, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ďurišová, M.; Kucharčíková, A.; Tokarčíková, E. Topical trends within the development of financial planning in an enterprise. In New Trends in Sustainable Business and Consumption [Print]: Conference Proceedings; EDITURA ASE: Bukurešť, Romania, 2019; pp. 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Dančišinová, L.; Benková, E.; Danková, Z. Presentation skills as important managerial competences in the context of professional communication. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 15, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlů, D. Marketingové Komunikace a Výzkum; Professional Publishing: Zlín, Czech Republic, 2006; p. 198. ISBN 978-80-7318-383-8. [Google Scholar]

- Frianová, V. Súčasné Prístupy k Hodnoteniu Účinnosti a Efektívnosti Marketingovej Komunikácie Podnikov. In Ekonomické Spektrum—Recenzovaný Vedecko-Odborný On-Line Časopis o Ekonómii a Ekonomike; Ročník, V., Ed.; CAESaR-Centrum vzdelávania, vedy a výskumu: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2010; Available online: http://www.spektrum.caesar.sk/?download=casopis%2001-2010.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2019).

- Mavragani, E. Greek Museums and Tourists’ Perceptions: An Empirical Research. J. Knowl. Econ. 2021, 12, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizanova, A.; Lăzăroiu, G.; Gajanova, L.; Kliestikova, J.; Nadanyiova, M.; Moravcikova, D. The Effectiveness of Marketing Communication and Importance of Its Evaluation in an Online Environment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dmitrijeva, K.; Batraga, A. Barriers to Integrated Marketing Communications: The Case of Latvia (small markets). Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 58, 1018–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stránský, Z. Úvod Do Studia Muzeologie; Masarykova Univerzita: Brno, Czech Republic, 2000; p. 172. ISBN 978-80-210-1272-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mudzanani, T.E. The four ‘C’s of museum marketing: Proposing marketing mix guidelines for museums. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis 2017, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Johnová, R. Marketing Kulturního Dědictví a Umění; Grada: Praha, Czech Republic, 2008; p. 288. ISBN 978-80-247-2724-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.-S.; Kim, J. Linking marketing mix elements to passion-driven behavior toward a brand. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 3040–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunan, D.; Di Domenico, M. Rethinking the market research curriculum. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2019, 61, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzempelikos, N.; Kooli, K.; Stone, M.; Aravopoulou, E.; Birn, R.; Kosack, E. Distribution of Marketing Research Material to Universities: The Case of Archive of Market and Social Research (AMSR). J. Bus.-Bus. Mark. 2020, 27, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Moharana, T.R.; Indibara, I. ICICI Prudential: Challenges in reaching the last mile. Emerald Emerg. Mark. Case Stud. 2020, 10, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.Y.J.; Schuett, M.A. Exploring expenditure-based segmentation for rural tourism: Overnight stay visitors versus excursionists to fee-fishing sites. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadarajan, R. Theoretical underpinnings of research in strategic marketing: A commentary. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2018, 47, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K.L. Marketing Management; Grada Publishing: Praha, Czech Republic, 2013; p. 816. ISBN 978-80-247-4150-5. [Google Scholar]

- Říhová, L.; Písař, P.; Havlíček, K. Innovation Potential of Cross-generational Creative Teams in the EU. In Problems and Perspectives in Management; LLC “Consulting Publishing Company “Business Perspectives”: Sumy, Ukraine, 2019; Volume 17, pp. 38–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, T.A.; Ahmad, J.H.; Malaysia, U.S. Public Relations vs. Advertising. J. Komun. Malays. J. Commun. 2015, 31, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloxsome, D.; Glass, C.; Bayes, S. How is organisational fit addressed in Australian entry level midwifery job advertisements. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesner, L. Marketing a Management Múzeí a Památek; Grada: Praha, Czech Republic, 2005; p. 304. ISBN 978-80-247-1104-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tillema, T.; Dijst, M.; Schwanen, T. Decisions concerning Communication Modes and the Influence of Travel Time: A Situational Approach. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2010, 42, 2058–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tržec, P.I. Paintings of Old Masters from the Collection of Ervin and Branka Weiss in the Strossmayer Gallery in Zagreb; Radovi Instituta za Povijest Umjetnosti: Zagreb, Croatia, 2019; pp. 231–241. [Google Scholar]

- Borea, G. Fuelling museums and art fairs in Peru’s capital: The work of the market and multi-scale assemblages. World Art 2016, 6, 315–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbancová, H.; Hudakova, M. Benefits of Employer Brand and the Supporting Trends. Econ. Sociol. 2017, 10, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, L.; Charles, V. The impact of consumers’ perceptions regarding the ethics of online retailers and promotional strategy on their repurchase intention. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 57, 102264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, D.J.; Justicia, B.A.; Ràfols, C. Dynamic group size accreditation and group discounts preserving anonymity. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2018, 17, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumbrăveanu, D.; Tudoricu, A.; Crăciun, A. European Night of Museums and the geopolitics of events in Romania. In Tourism and Geopolitics: Issues and Concepts from Central and Eastern Europe; University of Bucharest: Bucharest, Romania; Cabi Publishing: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017; pp. 264–279. [Google Scholar]

- Volkmann, C.; Tokarski, K.O.; Dincă, V.M.; Bogdan, A. Impactul Covid-19 asupra turismului din românia. studiu de caz exploratoriu asupra regiunii valea prahovei. Amfiteatru Econ. 2021, 23, 163. [Google Scholar]

- Brouder, P. The end of tourism? A Gibson-Graham inspired reflection on the tourism economy. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 20, 916–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC. Coronavirus: Six Months after Pandemic Declared, Where Are Global Hotspots? 2020. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-51235105 (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Kliger, A.S.; Silberzweig, J. Mitigating Risk of COVID-19 in Dialysis Facilities. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 15, 707–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppio, A.; Bottero, M.; Ferretti, V.; Fratesi, U.; Ponzini, D.; Pracchi, V. Giving space to multicriteria analysis for complex cultural heritage systems: The case of the castles in Valle D’Aosta Region, Italy. J. Cult. Herit. 2015, 16, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ližbetinová, L.; Štarchoň, P.; Lorincová, S.; Weberová, D.; Průša, P. Application of cluster analysis in marketing communications in small and medium-sized enterprises: An empirical study in the Slovak Republic. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dancisinova, L. Intercultural competences and cultural intelligence in professional English language teaching. Jaz. Kultúra 2020, 11, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Agwu, M.E.; Onwuegbuzie, H.N. Effects of international marketing environments on entrepreneurship development. J. Innov. Entrep. 2018, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Der Hoeven, A. Networked practices of intangible urban heritage: The changing public role of Dutch heritage professionals. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2016, 25, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Christensen, R.H.B. “Ordinal—Regression Models for Ordinal Data.” R Package Version 2019.12-10. 2019. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ordinal (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- Rabe-Hesketh, S.; Skrondal, A.; Pickles, A. Maximum likelihood estimation of limited and discrete dependent variable models with nested random effects. J. Econ. 2005, 128, 301–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- OECD. OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2020; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnik, T.; Maletina, O. Museum dialogue as an important component of marketing communication of a brand. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 483, 012050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, M.; Lehman, K.; French, L. Communicating marketing priorities in the not-for-profit sector: A content analysis of Australian state-museums’ annual reports. Corp. Ownersh. Control. 2015, 12, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidorchuk, R.; Grineva, O. Marketing Research of the Russian State Historical Museum Lecture-Hall Visitors. Mod. Appl. Sci. 2014, 9, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; He, Y. Application of Integrated Marketing Communication: Integrated Marketing Strategies of the Palace Museum’s Cultural and Creative Products under New Media Age. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Business and Information Management, New York, NY, USA, 5–6 December 2020; pp. 138–148. [Google Scholar]

| Predictor | Estimates | Analysis of Deviance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE β | p | O-R | χ2 | df | p (χ2) | |

| Offline activities | 4417.6 | 3 | <0.001 | ||||

| Poor | −0.713 | 0.175 | <0.001 | 0.490 | |||

| Satisfactory | 2.623 | 0.164 | <0.001 | 13.772 | |||

| Excellent | 7.620 | 0.210 | <0.001 | 1422.97 | |||

| Evaluation of Offline Activities | Would You Consider Visiting an Object Again? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definitely Not | Probably Not | Don’t Know | Probably Yes | Definitely Yes | |

| Cannot evaluate | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.9%) | 99 (45.6%) | 102 (47.0%) | 14 (6.4%) |

| Poor | 27 (5.6%) | 64 (13.3%) | 83 (17.2%) | 274 (56.8%) | 34 (7.0%) |

| Satisfactory | 0 (0.0%) | 164 (8.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1268 (61.6%) | 625 (30.4%) |

| Excellent | 0 (0.0%) | 22 (0.7%) | 1 (0.03%) | 231 (7.5%) | 2830 (91.8%) |

| Predictor | Estimates | Analysis of Deviance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE β | p | O-R | χ2 | df | p (χ2) | |

| Intent of a visit | 725.8 | 3 | <0.001 | ||||

| Educational program | 0.089 | 0.176 | 0.612 | 1.093 | |||

| Exhibition | −0.241 | 0.136 | 0.077 | 0.786 | |||

| Event | 1.861 | 0.075 | <0.001 | 6.431 | |||

| Intent of a Visit | Would You Consider Visiting an Object Again? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definitely Not | Probably Not | Don’t Know | Probably Yes | Definitely Yes | |

| Exposure | 24 (1.2%) | 53 (2.6%) | 85 (4.2%) | 1072 (52.6%) | 805 (39.5%) |

| Exhibition | 3 (0.7%) | 72 (17.0%) | 6 (1.4%) | 154 (36.4%) | 188 (44.4%) |

| Educational program | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 90 (51.7%) | 2 (1.1%) | 82 (47.1%) |

| Event | 0 (0.0%) | 127 (4.0%) | 2 (0.06%) | 647 (20.2%) | 2428 (75.8%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lukáč, M.; Stachová, K.; Stacho, Z.; Bartáková, G.P.; Gubíniová, K. Potential of Marketing Communication as a Sustainability Tool in the Context of Castle Museums. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8191. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158191

Lukáč M, Stachová K, Stacho Z, Bartáková GP, Gubíniová K. Potential of Marketing Communication as a Sustainability Tool in the Context of Castle Museums. Sustainability. 2021; 13(15):8191. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158191

Chicago/Turabian StyleLukáč, Michal, Katarína Stachová, Zdenko Stacho, Gabriela Pajtinková Bartáková, and Katarína Gubíniová. 2021. "Potential of Marketing Communication as a Sustainability Tool in the Context of Castle Museums" Sustainability 13, no. 15: 8191. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158191