1. Introduction

In the year 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially communicated the existence of a worldwide respiratory disease leading to severe pneumonia caused by an unknown virus. The first cases were reported from Wuhan, a city in Central China [

1]. The WHO declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global emergency on 30 January 2020 [

2]. Since then, the pandemic which has been affecting the planet can be analysed in social and economic terms of a pre- and post-COVID-19 pandemic time [

3]. On the one hand, a considerable health alarm sounded worldwide, with the collapse of many healthcare systems around the world and changes in individual behaviour patterns to minimise the contagion and the spread of the disease through the use of masks, more effective disinfection, limitation of social gatherings, greater safety distance, etc. On the other, the world saw an economic crisis with, for example, the closure of businesses, unemployment, changes to households’ purchasing power, higher food prices, and reduced food availability in local markets. No doubt the current feeling is one of uncertainty. Since the world is still living with the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak, it is not easy to estimate its long-term effects. Although society has been affected by various pandemics in the past, it is difficult to estimate the long-term economic, behavioural, or social consequences, as these aspects have not been extensively studied [

4]. The few studies available indicate that major historical pandemics of the last millennium have typically been associated with subsequent low asset returns [

5].

In the financial press, the effects of COVID-19 are often compared to the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008, which has been extensively investigated in the literature on interconnection, contagion, and spill-over effects [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Harvey [

11] establishes differences between the GFC crisis and COVID-19, the latter being an emerging pandemic that he has called the “Great Compression.” Some journalists and experts also compare the COVID-19 crisis with global wars, responding to the dramatic news from China, South Korea, and Europe, especially Italy and Spain, revealing that this new infectious disease is different and much more dangerous than past adverse events. The lockdown measures that many countries have implemented have affected businesses, job security, and essential services; some economists have argued that analysing financial variables as a response to COVID-19 is not conclusive, and that the focus should be on the physical quantities made available by the supply of goods and on the demand imbalances in the labour market [

12].

Strongly hit by this unprecedented emergency, many industries and sectors have been highly affected, including tourism. Tourism is a sector that depends on mobility and relies on leisure-time enjoyment, attitudes that have been limited in many countries since the first quarter of 2020. COVID-19 has had a significant impact on economic, political, and sociocultural systems worldwide. Health communication strategies and measures (for example, social distancing, travel and mobility bans, community lockdowns, stay-at-home campaigns, self- or mandatory quarantine, overcrowding control, etc.) have halted the tourism industry [

13,

14]. Countries such as Greece, Portugal, and Spain, which depend highly on tourism (exceeding 15% of the GDP), have been more affected by this crisis. Furthermore, exhibitions, conferences, sporting events, and other large gatherings have been abruptly cancelled, and cultural facilities such as galleries and museums closed [

4].

The tourism sector has gone through periods of total closure (due to government impositions) to periods of reinvention, seeking to adapt to the new situation and provide measures instilling health security in consumers. Tourists have quickly adapted to this new reality, wondering if some sanitary measures will disappear once the pandemic is over or if they will be permanent, thus avoiding possible similar situations in the future.

The large number of works published during 2020 and 2021 on COVID-19 focus on the effects of this virus at the economic level, hygienic measures for its prevention, and even the psychological effects on individuals, with fewer works focusing directly on tourism consumption, one of the most affected sectors. That is why the main objective of the present work is to analyse the changes in tourist behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic, looking at what factors influence tourists in the current state of health emergency and making a prediction of post-COVID tourist behaviour. This investigation represents an attempt to address several of these issues and approaches the situation in the tourism sector during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, the following objectives are set:

- RQ1.

Analyse tourists’ behaviour during the pandemic.

- RQ2.

Analyse what factors influence tourists in the current state of health emergency.

- RQ3.

Analyse tourism consumption expectations after the pandemic.

Therefore, a literature review is carried out on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on society, especially concerning new individual behaviour patterns adopted to avoid disease dissemination, particularly in the tourism sector. The empirical research consists of the gathering of primary data, which is then analysed. The methodology for collecting and analysing the data is a quantitative analysis carried out through a questionnaire given to tourists in Galicia, in the northwest of Spain, a region highly dependent on tourism. The total number of surveys collected was 712, from which the main findings and conclusions are presented in this study.

2. Theoretical Framework

Due to the magnitude of the current pandemic, one of the present issues in terms of societal change is personal behaviour associated with COVID-19 disease risk. According to the protective motivation theory, assessing the severity of a threat is one of the cognitive processes behind adopting protective behaviour [

15,

16]. Given the importance of behavioural factors in pandemic management, it is crucial to assess behavioural responses to the situation and determine how perceived risk is related to engaging in protective behaviours [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

Several essential theories emphasise the importance of social relationships as key drivers of human behaviour and optimal psychological functioning, such as self-determination theory [

24], Seligman’s PERMA model [

25], and Diener’s tripartite model of subjective wellbeing [

26]. Together, these theories identify the critical components of subjective wellbeing that situations can impact: for example, the onset of the COVID-19 outbreak, which lowered emotional wellbeing by 74 per cent, along with other changes (sleep patterns, for example) [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38].

In a very short time, society was forced to change its habits and implement a series of sanitary measures that would prevent the further spread of the virus. Teleworking was established in all possible cases, thus avoiding physical interaction with other individuals. Trips and flights were cancelled as a result of the lockdown-induced mobility reduction across regions. The million-dollar question experts are trying to answer is whether any of these changes will be permanent from now on, or if consumers will go back to their old pre-pandemic habits [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46].

Due to COVID-19, international, regional, and local travel restrictions were imposed worldwide, affecting national economies and obviously the tourism industry, particularly international travel, national tourism, and one-day visits, as well as other sectors such as air transport, cruises, public transport, accommodation, cafes and restaurants, conventions, festivals, meetings, or sporting events [

47]. Overall, with such a sudden slowdown in international air travel resulting from this crisis—from some countries’ travel bans, border closures, or quarantine periods—international and domestic tourism dropped dramatically.

Tourism is a sector with a major impact on all the world’s economies. It can be stated that one in ten jobs belong to this sector, accounting for approximately 10 per cent of global GDP [

48]. It is an industry with two agents involved: the individuals with a need to travel, and the supply of services that seek to satisfy the needs of the first group [

49]. Before the global pandemic, both agents were in continuous movement, with a continuous demand from tourists and a continuous stream of businesses at their disposal: transport, accommodation, catering, and tourism services, among many others. But this perfectly meshed industry has suffered one of the biggest setbacks in its history, coming to a virtual standstill. Certainly, the world, and especially this sector, was not expecting such a pandemic. No other infectious diseases or epidemics have ever managed to paralyse the world socially and economically, or even to stop international travel [

50]. Olympic Games [

51] and religious traditions such as Easter [

50] have been cancelled.

This pandemic has meant a before and after in society as a whole and in a very special way in the tourism sector. One has to bear in mind that tourism is a leisure activity, and right now individuals prioritise their health and safety. The current feeling is one of uncertainty. The most obvious uncertainty is how long the alarm situation will last and the timeframe in which different activities will recover. Time is always a crucial factor in determining the trajectory of processes [

52]. In the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries around the world implemented, and continue to implement, short-term travel restrictions to control the disease spread. For example, the United States initially cancelled travel to China and later imposed a travel ban on the United Kingdom and Ireland. As time has passed since the end of 2019, such restrictions have been implemented throughout all the countries of the world.

Professionals can observe past disasters, such as the SARS outbreak in 2003 [

53] and the tsunami in Arugam Bay, Sri Lanka in 2004 [

54], to obtain information on similar cases. Yet, somehow, the tourism industry has entered uncharted territory: compared to SARS, COVID-19 has brought more dire consequences to the global tourism market.

The experience of previous health crisis situations serves as a guide for action in the current pandemic situation. It is not the first time that a virus from the coronavirus family has affected society and, by extension, the tourism sector. In mid-March 2003, SARS-CoV, a severe acute respiratory syndrome, was recognised as a global threat. The first known cases of SARS also occurred in China, this time in the Guangdong province, and after five months the WHO declared the epidemic over on 5 July 2003. There were 8098 cases of SARS-CoV in 26 countries, with 774 deaths. Initially it was a health problem, but its consequences had a very significant impact on the tourism sector and changed the behaviour of international travel. Numerous academic papers and specialised magazines dealt with the subject. For example, McKercher and Chon [

55] warned of the transnational crisis that caused SARS and how the lack of coordination and the well-intentioned (but ultimately wrong) actions of governments can affect tourist flows. According to these authors, there was an overreaction among governments in the infected areas, motivated by a lack of experience in managing this kind of health crisis. The large-scale health crisis soon attracted the attention of the media. This crisis mainly affected Asian countries, such as China, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Vietnam. The number of passengers on international flights into Hong Kong fell by over 80 per cent in the year-on-year rate of change and the hotel occupancy rate fell from 90 per cent to 10 per cent in some cases [

56].

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, in a matter of months, the global tourism system framework went from overtourism [

57] to no tourism, and everyone will remember the harmful consequences that these circumstances had for destinations and, above all, the timeless images of hauntingly empty tourist attractions. Still, the general belief is that tourism will rebound as it did after previous crises [

58].

One year after the COVID-19 outbreak, there is still great uncertainty regarding economic activities and social life recovery. The tourism industry is a key sector in the immediate economic recovery of many countries, mainly for those whose economy is highly dependent on the industry. Williams and Kayaoglu [

59] stated that almost a tenth of European non-financial economic activities were related to tourism in 2016, and that these accounted for 9.5 per cent of employment among the EU workforce. The authors [

59] also asserted that the accommodation as well as the food and beverage sectors in the EU accounted for 19.7 per cent and 58.7 per cent, respectively, of overall employment in the tourism industry. On this basis, it becomes clear that both tourism-related companies and supporting companies will be facing unprecedented socioeconomic impacts as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic [

60,

61].

Gössling et al. [

47] compared the impacts of COVID-19 to previous epidemics/pandemics and other types of global crises and analysed how the pandemic may change society, the economy, and tourism. They came to the conclusion that the negative impact of epidemic outbreaks will be more significant in the tourism industry, and that there is a need to question the volume growth of current international tourism models.

The unprecedented nature, circumstances, and impacts of COVID-19 demonstrate that this crisis is not only different, but may engender profound and long-term structural and transformational changes for tourism as a socioeconomic activity and industry [

14].

Some authors [

62] refer to this pandemic as a transformative opportunity for the sector. Tourism not only has to recover, but it has to do it by reinventing itself [

63]. Furthermore, due to the sociocultural, economic, psychological, and political impacts of COVID-19, unforeseen trajectories are expected rather than historical trends, and the predictive power of “old” explanatory models may not work [

64]. What is still lacking is knowledge on how the crisis can drive industry change, how companies can turn this crisis disruption into transformative innovation, and how to conduct research that can enable, inform, and shape the rethinking and reestablishment of upcoming normality [

14].

Other authors [

65] predict a gradual adjustment in tourism, hospitality, and related sectors once the pandemic is over. The progressive reopening of businesses will gradually achieve results, requiring a minimum capacity to achieve profit. In cases where that will be impossible, government aid will be necessary to allow survival. Likewise, Assaf and Scuderi [

66] refer to previous crises that the sector has overcome, though this one has been the most devastating to date [

67].

As a result of this unexpected pandemic, many studies and proposals for the renewal of tourism have been published. One proposes a more sustainable tourism model. Sustainable tourism must seriously commit to the notion of limits, moving away from the present culture of consumerism and pro-growth ideology [

68]. The COVID-19 pandemic invites the tourism sector to rethink its business model, incorporating strategies to combat climate change. Instead of urging a return to pre-pandemic models, it is time to consider the tourism industry’s unsustainability and redesign it [

69]. As seen over this last year, in times of trouble, people focus on what matters in life: health, social interaction, environment, and identity [

70]; all human needs very compatible with tourism sustainability.

Other authors emphasise the role of new technologies in the new post-COVID era. Tourism is based on a traditional four-stage model founded on anticipation and preparation for the trip to a holiday destination, the experience at the destination, the return trip home, and the recollection afterwards [

71]. Being physically present has an obvious meaning for tourists searching for novelty and a getaway [

72], even in times of crisis. As governments impose new rules for travel, tourism must be prepared for a change in the era of disruption and digital transformation [

73]. Here is where technologies have become the key and drivers of change. Thus—and keeping the previous line of thought—ICT can contribute to a more sustainable future in tourism. Tourism companies are already using different forms of ICT to promote their attractions and destinations, a trend that derives from the COVID-19 crisis. For example, various destinations use virtual reality and 360-degree content technology for various purposes. Besides, the fundamental role of information technologies in communicating and facilitating commercial transactions and disclosing relevant information to decision-makers has evolved [

74]. At present, the promotion of live transmission platforms to avoid face-to-face contact, better information quality, or better system features have assumed an even more prominent role [

74]. Furthermore, digital and technological innovations such as chatbots to make reservations, voice assistants, butler robots, or QR codes should also be part of the new experience offered by companies in the tourism sector [

75].

It is important to reflect on the new hygienic-sanitary measures and protocols in the industry. Hygiene is the common denominator among various methods proposed by different institutions to face the current COVID-19 crisis. It is emphasised as a vital precaution to reduce the risk of the coronavirus spreading, and is intrinsically related to clean living. Hygiene has long been emphasised, and hotel hygiene is mentioned in many published studies [

76,

77]. Organisations are now serving customers who are very aware of hygiene and safety protocols. The study of Awan et al. [

78] therefore reveals an immediate need for the hotel industry to modernise its services for customers in the “new normal” mainly by adopting disinfection and sanitation activities, redesigning the general infrastructure, and introducing promotional offers. Since these hygiene conditions significantly impact customer behaviour and decision-making, hygiene management is very important in the context of the servicescape, such as in hotels. In particular, it is essential to emphasise the general hygiene protocols in hotels and among employees in public health disasters such as the ongoing COVID-19 crisis [

79].

The debate on determining when the pandemic ends or what it will take to declare the end of the pandemic divides health officials and politicians. So far, many of the answers have been either vague or sobering and have involved factors that can be difficult to influence. Scientists initially said it would take the vaccination of around 60–70 per cent of people to achieve herd immunity. The assumption at the time was that if around 66 per cent were immune because they had either recovered from the disease or had been vaccinated, the reproduction number (R) would fall below 1. Statistically, one infected person would then infect less than one other, and the pandemic would peter out as a result. However, the assumption now is that the new coronavirus is more infectious than it was initially, and scientists believe that around 80 per cent of people would have to be vaccinated for the pandemic to end [

80]. Potential herd immunity timelines are bifurcating as a result of the growth of different variants that may reduce vaccine efficacy. If the variants turn out to be a minor factor (they only reduce vaccine efficacy modestly, or they do not spread widely), then herd immunity is most likely in the third quarter for the United Kingdom and the United States and in the fourth quarter for the European Union, with the difference driven by the more limited vaccine availability in the European Union. However, if the impact of these variants is significant, we could see timelines significantly prolonged into late 2021 or beyond.

Moreover, herd immunity may look different in different parts of the world, ranging from nationwide or regional protection to temporary or oscillating immunity to some countries not reaching herd immunity over the medium term [

80].

In short, COVID-19 has had a significant impact on the world’s economic, political, and sociocultural systems. Health communication strategies and measures (for example, social distancing, travel and mobility bans, community closures, stay at home campaigns, self- or mandatory quarantine, overcrowding control) have stopped travel, tourism, and leisure at the world level. As an industry highly vulnerable to numerous environmental, political, and socioeconomic risks, tourism is used to and has become resilient in its ability to recover [

81] from various crises and outbreaks (e.g., terrorism, earthquakes, Ebola, SARS, Zika). However, the unprecedented nature, circumstances, and impacts of COVID-19 show that this crisis is not only different but may engender deep and long-term structural and transformational changes for tourism as a socioeconomic activity and industry. Indeed, on a global scale, the most distinctive features of this pandemic are interconnected and multidimensional impacts that challenge current values and systems and lead to worldwide recession and depression [

13].

4. Results

First of all, it is important to make clear that the findings presented are the results from the sample with whom the survey was conducted. The results are not representative of the entire population, especially in a period of great uncertainty in which the respondents themselves cannot respond with total confidence to what will happen after the pandemic. However, this study is a first approach, able to show preliminary results that shed some light on possible current and future scenarios.

It is essential to highlight that the analysed sample is quite balanced in gender, with 53.93 per cent women and 46.07 per cent men. The average age of respondents is 45 years, with a predominance of the age group 41–55 years (48.17%), followed by the considerably smaller 36–40 years age group (24.02%). Most of those surveyed had a university degree (73.74%) and were self-employed (66.01%). Regarding origin, 89.19 per cent of the sample were Spanish: in this case, 55 per cent were from outside Galicia, mainly from Madrid, Castilla y León, Catalonia, Andalusia, and the Valencian Community (

Table 2).

4.1. Tourist Behaviour during the COVID-19 Period

In this first section, tourist behaviour was analysed from 14 March 2020, when the Spanish Government declared the State of Emergency due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Until 21 June, there was a total lockdown; restricted mobility with due health measures was authorised after that.

From the total sample (n = 712), 390 individuals stated they had travelled after 22 June, representing 54.78 per cent of the total. After performing the Pearson chi-square test, no significant differences were seen in the gender variable (χ2 = 0.332), with equal travelling regardless of gender.

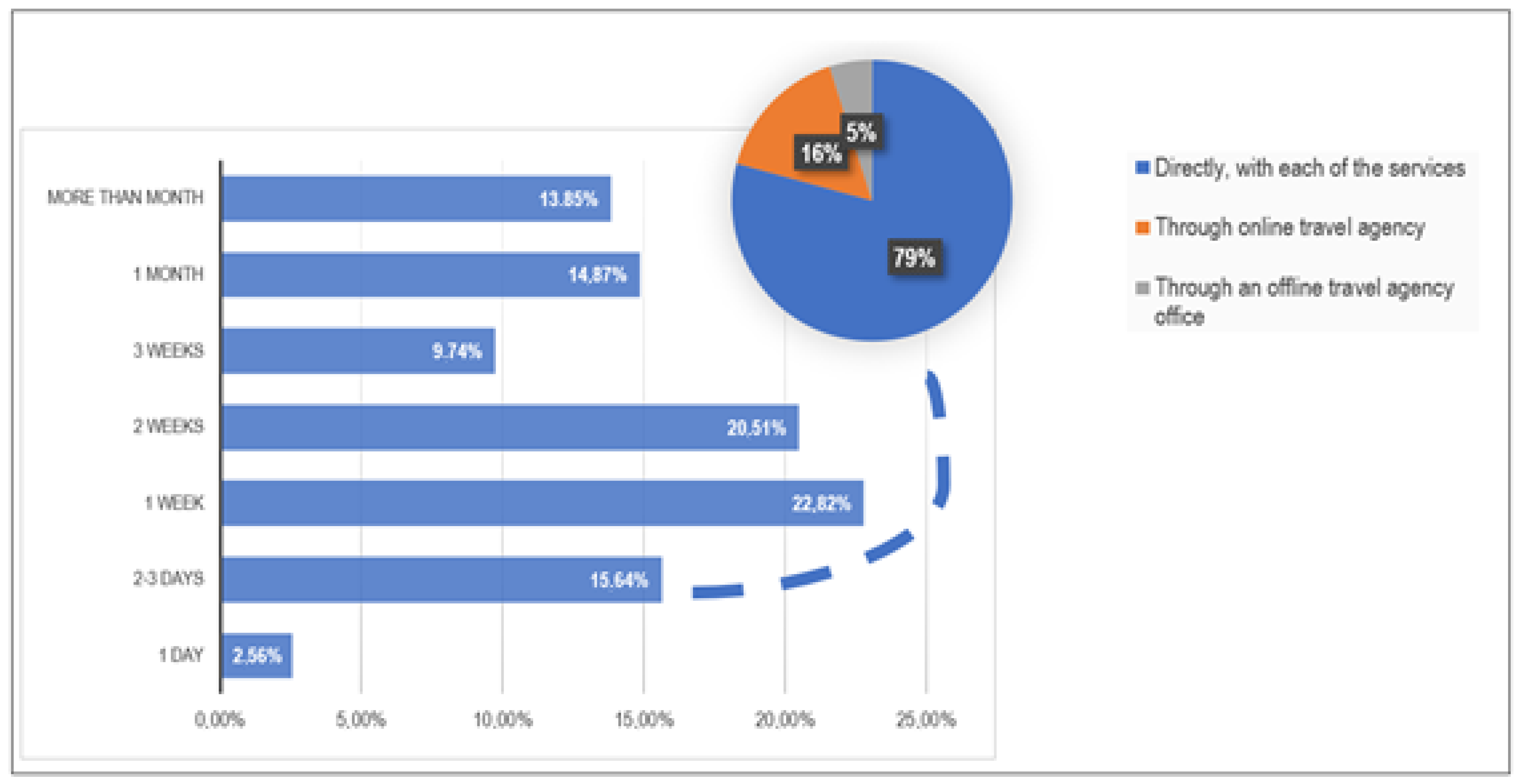

During this period, the travel planning margin was much shorter than the usual average. According to Google [

83], travellers make a reservation 12 weeks before their trip, on average; in the analysed sample, 43.33 per cent of respondents began to plan their trip between one and two weeks in advance. Regarding booking mode, the online channel was preferred by the majority (95.10%), either through an online retailer or directly with the service provider, the favourite option (79.25%), thus following the pre-pandemic trend (

Figure 1).

There was also an inevitable change in the means of transport used to travel in this period, where 69.29 per cent used their own vehicle, pushing public transport into residual use, with trains and buses representing less than 2 per cent each.

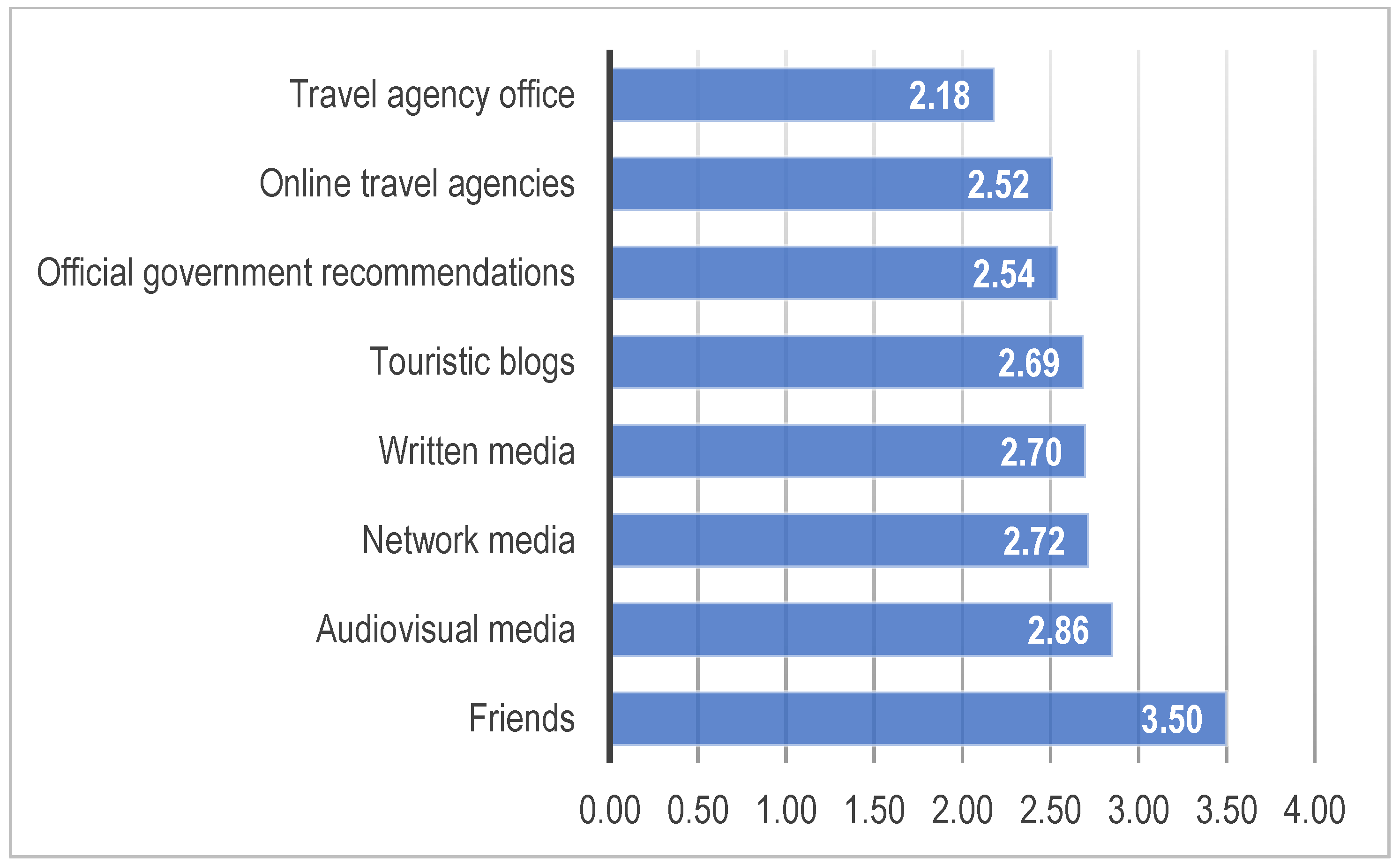

Concerning sources of information, tourists prefer to know about tourism activities (

Figure 2) by friends (30.36%), followed by online tools: social networks, travel blogs, and online travel agencies. Physical travel agencies were rarely used, used by only 4.46 per cent of those surveyed. Online platforms such as Booking.com or Airbnb, tourist office services, or even the destination experience itself were not even mentioned.

During the pandemic, internet use skyrocketed, something fully expected in the face of home confinement. The most popular devices used to access information in this period were mobile phones and computers, accounting for 44.23 per cent and 40.28 per cent, respectively.

Another factor to consider when reflecting on tourist consumption is the role of the digital influencer, who is a source of inspiration and advice for other digital consumers. Their posts’ originality and uniqueness are key factors for their effective content marketing having a considerable weight in consumer decision-making and choice. During the pandemic, family and friends continued to be the leading influencers (average of 3.93 out of 5), confirming previous tourism consumer behaviour and consumption results in general. However, it is noteworthy that the second highest influence was sanitary security (3.86 out of 5), an indicator not valued before the pandemic. Standard variables such as public safety and price followed (

Table 3).

Possible significant differences in gender and age variables in the surveyed sample were also analysed. For that, the non-parametric Pearson chi-square test was applied. The results indicate that there is no statistically significant difference in the gender variable, showing parameters higher than 0.05. However, the age variable showed statistical significance, certain ages showing more significance in each indicator (

Table 4). For example, the relationship is strong in citizen security, though the influence is lower in the 25–32 age group and, in some indicators, in the 50–60 age group. Sanitary security is also an indicator that has a significant influence, but to a lesser extent in the 23–40 age group.

An analysis of possible correlations was also carried out, applying Pearson’s ρ statistic, a p-value of 1 showing the strongest correlation. Results show that all values are close to a p-value of 0.000, which signifies that the difference between the two indicators is statistically significant, and thus there are no correlations.

The last two factors examined in this section were accommodation and activities carried out. Regarding accommodation, the preferred option during the pandemic for 34.79 per cent of the sample was hotels with three stars or more, followed by home stays with family and friends (13.70%). Tourist apartments, rural accommodation, and villas were ranked more or less the same, around 10 per cent (

Figure 3).

Regarding the tourist activities carried out during the holiday stay within the pandemic period, three stood out: (i) use and enjoyment of the beach/coast, sun and beach tourism being the leader during this period; (ii) visiting tourist destinations, and (iii) gastronomic tourism. These choices are followed by trekking and visits to natural parks with percentages above 40 per cent, reflecting the growing interest in green or natural spaces and outdoor physical activities. On the other hand, activities such as attending conferences, spas, or sports events represent a minority during the pandemic, with percentages below 10 per cent (

Figure 4).

4.2. Post COVID-19 Period

Section II refers to a post-COVID period and analyses tourists’ consumption expectations once the pandemic is over and the WHO declares the new coronavirus as endemic or herd-immunity is achieved with vaccination.

It starts by evaluating a series of tourists’ consumption expectations using a numbered semantic differential scale, from 1 to 5, within the frames of multi-point rating options:

Distrustful of tourism—Confident of tourism

Cautious—Bold

Not willing to travel—Willing to travel

Put safety first—Put leisure first

Book in advance—Last minute reservation

Cancellation insurance contract—Lower price avoiding cancellation insurance

Use of private transport—Use of public transport

Tourism in rural destinations—Tourism in urban destinations

Tourism in inland destinations—Tourism in coastal destinations

Most of the opposites showed intermediate values, close to 3, reflecting a neutral position of respondents with no evidence of a clear trend towards either extreme. However, there are three propositions whose values were higher than 3, revealing that people continue to show confidence in tourism (3.59). To be more precise, 32.43 per cent of individuals in the sample are more confident of tourism, with a tendency evaluation of 4, compared to the 4.59 per cent who completely distrust the tourism sector (grade 1) or the 10.04 per cent who just distrust it (grade 2). The analysis “Not willing to travel/Willing to travel” also brings excellent insights for the sector, as 52.94 per cent of the sample answered that they were willing to travel (grade 4) or very willing to travel (grade 5). Two other clear trends were perceived from this first data analysis. Firstly, tourists prefer to use their own vehicles over public transport, with 42.75 per cent choosing grade 1 (use of private transport), followed by 18.51 per cent of the respondents whose tendency is to use their own means of transport (grade 2). Secondly, the tourists are disposed to put safety before leisure: 53.23 per cent of the sample valued safety most, and 33.14 per cent settled on an intermediate grade; only 13.63 per cent valued leisure more than security.

An ANOVA analysis (

Table 5) of these nine variables was carried out with the independent variable gender. The only significant differences obtained were in the variable “Cancellation insurance contract/Lower price avoiding cancellation insurance.”

As shown in

Figure 5, although the mean values are very similar, the female population is more representative of valuing purchases with cancellation insurance (value closer to 1).

Related to one of the differential scale items (“Willing/Unwilling to travel”), respondents were confronted with a straightforward question: will they maintain the same number of journeys after the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic times? The results obtained support the tourism industry, as 56 per cent of the sample expect to keep the tourism consumption level and 32 per cent even to increase it.

The analysis continues by assessing the most consumed types of tourism post- pandemic. The results do not show clear preferences, distributing tourist consumption among various typologies. However, with values between 3 and 3.5 (out of 5) and a decreasing order of preference, nature tourism was the top preference once the pandemic is over, followed by gastronomic tourism, sun and beach rural tourism, and cultural tourism. At the bottom of preferences were wine tourism and sports tourism, followed by MICE tourism, as in the pandemic.

As for the means of accessing tourism information after the pandemic, tourists preferred friends’ opinions, confirming the attitude during the pandemic. It is relevant to note that audiovisual media gained importance compared to the pandemic period, where they ranked fifth behind social networks or tourist blogs. Again, travel agency offices are relegated to last place, with decreased consumption (

Table 6).

Governments’ official recommendations emerge as a novelty, though they are still minor sources of information (

Figure 6).

Following the same analysis procedures as for the pandemic period, the way tourists will access tourist information after the pandemic was verified. The highest scores (more than 4 out of 5) indicated two protagonists: the computer and the mobile phone, reversing the order presented during the pandemic, where the mobile phone ranked first and the computer second (

Figure 7). As mobile phones will explode in popularity, the tourists were also asked about their preferred payment methods, as smartphones can be used for mobile banking. The traditional credit or debit card will continue to be the preferred option over the mobile phone or other telematic alternatives (Bizum or mobile banking).

This study also set out to determine which will be the leading tourism decision-making influencers after the pandemic. The first five factors coincide with the indicators during the pandemic, and in the same order, with a slight growth in values, representing an even more decisive influence. The indicator that comes in sixth place, sun and beach, will be vital as a destination after the pandemic is over, with a rating of 3.28 compared to the 2.87 received during the pandemic. Cancellation insurance appears with a rating slightly above 3, indicating that groups in the sample will value this factor when making a reservation in the post-pandemic period. It is worth highlighting that after the pandemic, the surveyed tourists will also value a rural destination, with a score of 3.14 compared to 2.74 during the pandemic (

Table 7). Factors such as tourism quality certifications and the destination’s proximity to home will not be influential once the tourism situation returns to normal.

Once again, the non-parametric Pearson chi-square statistic test was applied to analyse whether significant differences were dependent on gender and age variables. In the case of gender, no statistically significant differences were identified in the post-pandemic period except for the influence of family/friends (χ

2 < 0.05). The male gender will be more influenced by the family/friends indicator when choosing a tourism destination. Regarding the age variable, as was seen during the pandemic, there were no statistically significant differences in any of the indicators. After the pandemic, in the case of the indicators such as gastronomy, rural destination, urban destination, comments about the destination in social networks, and the existence of a quality seal certification, no differences in valuation were observed in the total sample (

Table 8).

An analysis of possible correlations was also carried out, applying Pearson’s ρ statistic, a value of 1 showing the strongest correlation. As during the pandemic period, these results showed all values close to a

p-value of 0.000, with no correlations between indicators (

Figure 8).

Further analysis also reveals a lengthened travel planning period, 29.88 per cent of respondents believing that they need more than a month to plan their travels and 21.92 per cent at least one month. This compares with 43.33 per cent of tourists who planned their trips between one and two weeks ahead during the pandemic.

A majority (42.82%) will buy and reserve tourism services for the post-pandemic period, doing so either directly with the providers or using reservation platforms.

Table 9 shows all the possible combinations, since this question in the survey was posted with multiple answers. The second option is to directly use reservation platforms such as Booking.com (26.76%). Other combinations show percentages lower than 7 per cent, well below these first two alternatives.

Finally, the means of transport and type of accommodation variables were subject to statistical analysis.

The car will continue to be the preferred vehicle, with a rating close to 4 out of 5, meaning a high probability of being used. With an average of more than 3, the aeroplane comes next, a means of transport only used by 14.17 per cent of the surveyed population during the pandemic period (

Table 10). Preferences regarding means of transport are to be maintained during and after the pandemic, except for buses and trains, which switch positions, train trips being preferred over bus trips in the post-pandemic period.

To finish, it is worth mentioning that hotels with more than three stars and spa hotels will be the accommodation chosen by the majority of the sampled tourists after the pandemic. During the pandemic period, three-star hotels were also the first option, while hotels with spas ranked seventh. The option of staying with family or friends ranked second during the pandemic but now ranks fifth. Rural accommodation has also risen in the ranking to the second position (

Table 11).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The beginning of the year 2020 promised a record year for tourism in Galicia. Hotels, tourist apartments, and campsites had registered a significant increase in overnight tourists stays by both residents in Spain and foreign tourists. Only rural tourism had started very weakly compared to the first two months of 2019. The pandemic caused a significant and generalised decrease in demand for regulated tourist accommodation establishments. The breakeven was achieved in August, mainly due to domestic tourists.

Tourist apartments best withstood the effects of the health crisis, even in August, as the number of guests has increased compared to 2019. On the other hand, business travel experienced a sharp drop due to the effects of the pandemic, which caused a substantial decline in travellers staying in regulated tourist establishments, mainly in the second and fourth quarters of the year.

Responding to the first objective (RQ1), it is concluded that during the pandemic, in the temporary periods when mobility was allowed, tourist activity did not come to a complete halt in Galicia. Just over half of the analysed sample (54.78%) travelled during the COVID period.

Using the internet (mainly social networks) to access tourist information and to make reservations has proved to be the current and future trend of trade tourism services. Physical travel agencies are relegated to very specific or complex products/packages or to the organisation of trips to exotic/distant destinations, where going to a physical agency provides greater security to the tourism consumer. Furthermore, the mobile phone and the computer are the most widely used devices for accessing tourist information and making reservations and will continue to be so in the post-pandemic period. Health security ranks second in factors deciding tourist choice, something verified in previous studies [

65,

66], only surpassed by the opinions of family or friends. The price factor has maintained first place, something that already conditioned travel decisions before COVID-19 (RQ2).

Three-star hotels are the type of tourist accommodation most used during COVID-19. The most popular activities are use and enjoyment of the beach/coast, along with visits to tourist destinations and gastronomic tourism, trends already popular before the pandemic. In the post-pandemic period, hotels with more than three stars are expected to continue to be the favoured accommodation, with spa hotels also taking on importance here, something that did not happen during the pandemic (it should be noted that many remained closed for much of the year 2020).

In response to RQ3, it is concluded that once the pandemic is over, these times will be present in people’s minds for a long time. Particularly, tourists will reward safety over leisure and maintain a certain tendency to prefer their own vehicle for tourist travel, which occurred during the pandemic period. In addition, health security will be a requirement when consuming tourism. There is good news for the tourism sector: travellers’ trust will be rebuilt and tourists will be travelling again.

During the pandemic, travel planning periods were substantially reduced, but once this situation is over, tourists will again plan their trips further in advance, returning to average values of more than a month.

Nature tourism, sun and beach tourism, rural tourism, and cultural tourism will emerge more decisively in the post-pandemic period. There is a certain tendency to avoid mass tourism, cruise tourism, or MICE tourism, at least in the medium term. Experts believe that a “new normal” will return one year after the pandemic is declared over, with international mobility still reduced, but with automobile dominance. In two years, tourism activity will practically return to normal, as in pre-pandemic times.

The tourism industry had to come to a stop due to the pandemic and sanitary restrictions. Against such a backdrop, the opportunity arises for destinations to take advantage and rethink what kind of destination they want to be, what kind of tourism they want to attract, what relationship they want to build with residents, what social and economic impacts they want to generate, and what strategies they need to implement—that is, to reflect on everything that can bring improvement and sustainability. That new or reconsidered vision of the destination should determine what actions need to be implemented to be proactive (rather than reactive) against COVID-19 or other future adversities. What matters is that destinations have an opportunity to define their identity and determine their marketing positioning. This is not a new conclusion derived exclusively from the pandemic, but rather a basic marketing principle that is also appropriate in this situation.

Based on the results obtained, in terms of implications for the sector, it is relevant to mention first a strong probability of a return to normality relatively quickly, something that has happened in previous crises and is shown in other studies [

54,

55]. Businesses closed for most of the year 2020–2021, such as spas, must plan communication actions in order to attract and regain customers. Among the commercial strategies and actions to be carried out from now on, all companies in the tourism sector must promote digital and online media chains, as these have been widely accepted during the pandemic and will most likely continue to increase their number of users. Previous studies predicted greater digitisation of the sector, as seen in the theoretical review [

71,

72,

73,

74,

75]. Information searches, reservations, and purchases will be carried out online by a greater number of tourists, making it necessary to strengthen and improve this path. It is also believed that domestic tourism will increase due to medium-term restrictions on international tourism, and that most tourism movements will be by road and train. Empathy and sustainability will be relevant values for tourists when the confinement ends, as Chambers et al. [

68] advocated. For this reason, the emphasis has to be on human values and the tourist experience, respecting the measures in force at all times in relation to social distancing and safety. After the pandemic, certain aspects that gained great importance during the pandemic and had to develop at an accelerated pace, such as health security [

65,

66,

68], will no longer be an added value in this sector but a minimum required by the tourists, it being necessary to maintain these guidelines over time. In addition, certain sectors, such as cruise tourism or MICE, will have to make greater efforts, adopt greater security measures, and carry out promotional campaigns to regain their market share, as these types of tourism are more difficult to reactivate because they are considered to involve greater numbers.

Additionally, as specific conclusions for the destination Galicia, it is important to add that, despite the fact that this community depends largely on tourism, tourism there is not excessive. Galicia does not follow a mass tourism model in the manner that other destinations in the south or east of Spain do, where the confinement and paralysis of tourism has shown a greater impact. In Galicia, the pandemic has been pronounced, especially in periods of lockdown, but during the rest of the year, and especially in rural destinations, not all tourism has been affected in the same manner as in other destinations. Moreover, some experts affirm that the pandemic has promoted other types of tourism, such as the less crowded rural or interior tourism, an area in which Galicia has a great deal to offer. Indeed, internal tourism has been greater this year, with Galicians themselves undertaking tourism in Galicia. The discount vouchers offered by the Xunta de Galicia to residents to practise tourism in Galicia have encouraged this attitude. Also, the promotional campaign for the most mature product of this territory, El Camino de Santiago, which allows a very dispersed and low mass tourism, has not suffered from a huge decrease in tourists. In addition, it has been extended to the Ano Xacobeo in 2021–2022 to further encourage this particular tourism. Therefore, the impact has not been as great as predicted at first.

As limitations of this study, it is worth mentioning that the data collection was done in the middle of the pandemic, during 2020, in a scenario of great uncertainty. The questions asked through the questionnaire seek to predict tourist behaviour after the pandemic period. This is something very complicated in a period of so much uncertainty in which the respondents themselves, and not just a representative sample of the population, show doubts about the future. It would be necessary to carry out a second investigation once this situation ends and normality returns, verifying if the expectations concur with actual behaviour. For this reason, future research will analyse tourism behaviour after the pandemic, checking the new behaviours and verifying whether they are in line with those before the pandemic, or if, as a result of this exceptional situation, new consumption patterns have been adopted in the tourism sector.