Abstract

An emphasis on providing authentic and inclusive educational experiences to students has been recommended in many educational systems as essential for motor, social, and psychological development. Despite the focus of recent studies on the preparation of physical education (PE) teachers for entering the profession, little attention has been paid to beginner teachers and how these teachers can promote educationally rich PE experiences. Therefore, this study sought (1) to understand how a novice PE teacher implemented the cooperative learning model and shared the responsibility for teaching–learning processes with students; and (2) to examine students’ perspectives about their cooperative experiences and student-centered learning. Participants included 25 high school students and one novice PE teacher. Through an action-research design, data were collected by utilizing three qualitative techniques and analyzed using thematic analysis. CL was found to be a complex model that needed time to be implemented effectively and allow students to take advantage of its potential. The development of cooperative relationships allowed students to assume greater responsibility in the lessons. Novice teachers should be encouraged to adopt CL and promote a gradual process of sharing responsibility with students.

1. Introduction

The premise that pupils learn better when they learn together through negotiation, cooperation [1,2], teamwork, and commitment to others is increasingly acknowledged as essential for motor and psychological development [3]. In line with scientific evolution [4], the development of these competencies, in addition to skills such as communication, has become fundamental and useful for the students’ future careers [5,6,7].

Cooperative Learning (CL) has been seen as a student-centered model (SCM) capable of promoting students’ active engagement [8] and improvement. The model has five elements: positive interdependence, appropriate social skills, promotive face-to-face interaction, individual accountability, and group processing, which have been identified as critical and are widely described in the literature [9,10]. Namely, in Physical Education (PE), CL has been important in the four learning domains, i.e., physical, cognitive, social, and affective [9]. Particularly, from CL, students can improve their ability to listen to others, construct understanding together, and respect, encourage, and support each other to learn [11,12,13].

Despite the high volume of research conducted in the last two decades on CL, the use of this model in PE has been studied much less [9], arriving earlier in other curricular areas such as Science, Math or English [14]. In general, PE literature has suggested that CL (1) can be used in a great variety of curricular contents such as team sports (e.g., volleyball, basketball, football), individual sports (e.g., table tennis) and sports related to health and basic motor skills [15]; (2) has been mostly investigated in primary and secondary education; (3) with the main purpose for understanding the model effects in students’ motivation [16].

From a teaching point of view, however, in CL, teachers need to promote students’ ability to cooperate and deal with potential conflicts and divergent ideas [17]. This requires teachers to abandon traditional and authoritative roles, in which the teacher is the full instructional leader, and start acting as facilitators of student-centered learning [2,18,19]. This involves ‘developing students’ capacity to become their own teachers and supporting them to know how to assess knowledge claims, how to learn (…) to seek help (…) how to be resilient (…) and helping students know what to do when they do not know what to do’ [19] (p. 275). As facilitators of student-centered learning, teachers should: (1) see learners as central actors in the teaching–learning process [20]; (2) empower them to take responsibility for and control of their learning experiences [2,21]; (3) guide students to be sensitive to each other’s ideas and work with each other cooperatively [21]; and (4) modify activities to meet learners’ developmental needs to optimize their success and engagement [2]. This allows students to have a more proactive role in their own learning experience [18].

Importantly, the innovation of teaching practices often requires a shift from long-established ‘traditional’ (i.e., teacher-centered) forms of education. Although the process of teaching practice renovation, as it relates to school implementation of CL or other SCMs [22], has been found to be highly complex, most existing research has examined this phenomenon somewhat at a ‘surface level’ (e.g., most research protocols are of short duration). Research has shown, essentially, that teachers appreciate the fact that CL is less directive and therefore more engaging to students [11,23] and that teachers face numerous challenges in trying to adhere to a long-lasting and sustainable adoption of CL in their PE lessons [12]. Overall, most research has been conducted with experienced PE teachers who seem to have trouble coping with the pedagogical demands of practically implementing the CL elements, typically displaying a lack of conceptual clarification about the educational purpose of CL [24].

This problem is even more relevant in the case of pre-service teachers (PSTs) and teachers at the beginning of their professional careers (novice teachers) (NTs) [25]. On the one hand, the (future) teachers are still struggling with building effective (general) teaching skills. On the other hand, the effective implementation of CL implies the operationalization of complex instructional strategies (associated with the role of facilitator: e.g., empowering and transferring decision-making to students and mediating social interactions and cooperative problem solving) [26], which may come as an additional challenge to beginner teachers. In addition, research shows that effective physical education teacher education (PETE) programs, PSTs’ teaching practice during their school placement, and the professional practice of beginner teachers in the first years in the profession are fundamental mechanisms for the renovation of the PE curriculum in schools (mainly through the implementation of SCMs) [22]. Nonetheless, although recent studies have focused on the preparation of future teachers (PSTs) during their school placement experiences [27], there is a marked dearth of research aimed at investigating the experiences of beginner teachers.

Conducting research on beginner teachers is particularly relevant, for it is known that the experiences lived, and the skills and conceptions developed, during these years are important indicators of their future professional practice (e.g., adhering to CL) and because it is the first moment when they have to work completely independently without support, for example from their university supervisors (unlike PSTs who have that support) [28]. In addition, to our knowledge, only two studies have conducted research on CL as implemented by NTs [13,26]. These studies contributed important information about the impact of CL on girls’ engagement [13] and the barriers and facilitators of purposeful technology integration when using CL in PE [26]. Nonetheless, this research has not captured the students’ voices, feelings, and perceptions about their lived experiences and thus the knowledge generated did not allow us to understand the reasons for their attitudes towards PE and how the teachers’ intervention may have impacted on that [29]. Allowing young people to share their opinions with teachers [30] can be a transformative practice, empowering them to thrive and improve their experiences of schooling [31].

A knowledge gap in the students’ perceptions and feelings exists and can likely best be understood through qualitative investigations [29] so that practitioners can become aware of students’ specific actions and the reasons that lead them to act in a certain way [24]. Furthermore, a recent systematic review on CL [24] showed that almost half of the articles used a single didactic unit of 8–12 lessons, a unit length that seems to be insufficient to allow us to affirm that the positive results observed are a consequence of this short implementation. CL needs a larger number of lessons to be fully developed, particularly when the students and teachers do not have extensive previous teaching experience [27]. Indeed, longer didactic units with an intervention-focus have been enabling teachers to progress from a frustration state, where they experience a negative impact of their non-successful intervention on students’ participation and learning, to a stage where they could effectively help students through improved teaching skills [26].

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to (1) understand how a novice PE teacher implemented the CL model and shared with students the responsibility for teaching–learning processes; and (2) to examine students’ perspectives about their cooperative experiences and student-centered learning.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

We recognize that teaching is multidimensional and subjective and that knowledge is socially constructed [32]. Consequently, when investigated, the educational context can assume several different perspectives. According to this assumption, this study is framed upon an interpretative paradigm, underpinned by epistemological constructionism [33], in which the primary interest is to understand and illuminate the human experience [34] and to contribute to the deepening of knowledge in a particular field of human activity (e.g., the educational setting within PE).

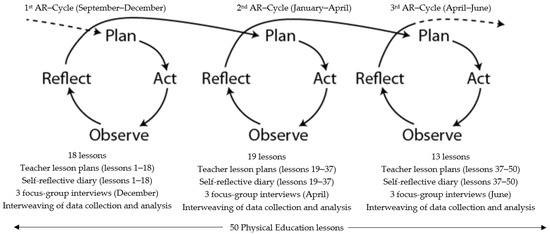

In agreement, this study adopted an action research (AR) design, where the teacher assumed the dual role of teacher–researcher [26]. An AR design reflects an epistemology capable of keeping pace with the dynamic and situated development of teaching and learning within SCMs [35], tallowing a dialogue and negotiation between the teacher and the pupils [36,37]. The project involved three AR-cycles (that corresponded to the three school terms) with each cycle including the processes of planning, acting, observing, and reflecting on practice [38] (Figure 1). All processes were centered on the events emerging during the program implementation. The first cycle served as a diagnosis of the preliminary problems encountered related to how to learn cooperatively and at the end of each term, students and the teacher’s reflections and fact finding about the process worked as the action steps and planning for the following cycles.

Figure 1.

Action-research timeline.

2.2. Participants

This study comprised 25 students aged 16–17 years old enrolled in the 12th grade at a high school in Portugal. The female NT (25 years old) had two years of experience, one year as a PST and another as a PE teacher in another school. This research allowed her to consolidate her previous experience, which she gained during her master’s degree (Physical Education Teaching in Basic and Secondary Education), and she was also a PhD student on the Doctoral Program in Sports Science. The co-authors, the silent partners in this paper, were experienced academics and had expertise in the use of SCMs and they acted as advisors and as peer-debriefers to challenge the teacher’s interpretations throughout the process. Together, they discussed data collection and analysis. The University Research Ethics Committee granted ethical approval for the research project after all participant students and respective legal guardians signed the informed consent.

2.3. Units

The intervention lasted a full academic year (from September to June) and was applied during regular PE classes (twice per week, 90-min per lesson). According to the PE national curriculum guidelines, eight units of multiple sports were applied (First school term: Futsal, seven lessons and half; Dance, six lessons and half; and Badminton singular, four lessons; Second school term: Volleyball, 10 lessons; Badminton pairs, five lessons; and Athletics, four lessons; Third school term: Basketball, 10 lessons; and Athletics, three lessons). Each sport discipline began with a diagnostic assessment of students’ sport abilities, to be able to divide them into heterogeneous ‘learning teams’ [10]. Following this lesson, subsequent lessons focused on an athletic pursuit and in each of them there were planned activities to help the students to develop their skills and strategies in working with others and have an active role in their teaching and learning process. While there was not a specific validation strategy, in order to maintain a level of model fidelity [12] and to offer a pedagogical scaffold for organizing group work [10], teacher use of CL was guided by the five CL key-elements, the additional procedures of teacher as facilitator of learning, and students’ roles and responsibilities (see Table 1 and Table 2 for further details).

Table 1.

Overview of the year-long CL curriculum (common procedures in the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd AR-cycle) [2,10].

Table 2.

Focus of each AR-cycle [2,10].

2.4. Data Collection

Data were collected throughout one academic year using multiple qualitative sources to gain an exhaustive understanding of the topic under study [39]. Teacher lesson plans included the design of each learning situation that was intended to respond to the Portuguese PE program and to promote student-centered learning, in which social development is paramount, being adapted whenever necessary [40]. The teacher’s field diary was used to describe and reflect on the problems encountered by the teacher and her students and the strategies used to overcome them and express detailed descriptions of what she felt she could have done better and what worked well, and the goals set for the next lesson [35]. Three semi-structured focus-group (FG) interviews were conducted at the end of each school term (nine in total) with two purposes: allow students to discuss their opinions, understand peer interactions, and gauge each other’s views [41]; and to understand whether the teacher’s intervention was having an effect and what needed to be changed [41]. In order to prevent students from feeling pressure to reach a consensus or to agree with each other, they were encouraged to share their ideas in a comfortable way, and all points of view were valued [42]. FG were conducted after the school day in the participants’ school settings, each interview was video recorded, lasted approximately 90–130 min, and was transcribed verbatim.

2.5. Data Analysis

In keeping with the on-the-spot, interactive, and cyclical nature of AR, data collection and analysis were intertwined. As per the procedures followed in other research [43], a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive theme development was used to analyze the data [44]. The study began as being deductive in nature because of the primary role that CL and the student-centered approach played in formulating research and interview questions. The study became more inductive during the data analysis [45], with the purpose of generating new explanations and theories from the specific data [42].

A thematic analysis was used to evaluate data due to its potential to enable the researcher to identify, analyze, and report patterns (themes) within the data set [46]. A theme captures something important expressed in the data in relation to the investigated problem and its relevance is not dependent on quantifiable measures [47]. The initial stage involved immersion and familiarization with the transcribed data. Specifically, this involved reading the texts several times and identifying segments of data containing meaningful information. The second phase involved the production of initial codes from the data, and basic segments deemed meaningful were attached labeled. This process developed with pre-existing research aims in mind (deductive), alongside openness to new segments (inductive) and was completed manually by hand—which enabled us to generate the coding scheme. The third phase involved the creation of themes by addressing concepts, and sorting codes into themes. Constant comparison was employed, leading to the amendment of themes for the initial phase four grouping of overarching themes, themes, and subthemes. In this process, four original main themes emerged: theme 1, communication, knowing how to listen and accept opinions/criticisms; theme 2, trust and union relationships; theme 3, positive interdependence; and theme 4, helping each other. The last phase involved going back through the data to name the identified themes in a more representative way.

2.6. Data Trustworthiness

The dual role of teacher–researcher implies a high engagement in the study as an insider [48], being recognized as either a weakness or a strength of this study [26]. To acknowledge the potential consequences of researcher presence and to establish a balance between closeness and distance [48], multiple trustworthiness criteria (replacing the ‘usual positivist criteria of internal and external validity, reliability and objectivity’ [49] (p. 14) were adopted. Namely: data triangulation, which referred to the use of multiple data collection sources in order to describe the phenomena through different perspectives [50]; regular peer debriefings and collective interpretational analysis among the research team to minimize the risk for individual researcher bias in the interpretational analysis [42]; and students were frequently asked about the implicit meanings of their actions and verbal interventions [51]. By doing so, the accuracy of the results was increased [52].

3. Results

Data analysis generated three main themes representative of NT implementation of CL and sharing the responsibility for the teaching–learning process with students. Students’ perspectives about their cooperative experiences and student-centered learning included: (1) resisting cooperative learning; (2) accepting cooperative learning; and (3) embracing authentic personal commitment to cooperative learning.

3.1. 1st AR-Cycle [September 2017–December 2017]—Resisting Cooperative Learning

3.1.1. Point Zero, First Reactions to CL: Struggling with the Basics, Talking to Each Other, and Working Together toward a Common Goal

The first lessons of the year were dedicated to the instructional units of Football and Dance and aimed to develop the following CL elements: appropriate social skills and promotive face-to-face interaction. In this way, learning situations that promote work in small groups and that require communication, understanding, and cooperation between students were planned. The following examples of activities support this idea. ‘Ball to the captain: the team in possession of the ball have to pass it between all their elements before it reaches the captain. The opponent attempts to regain ball possession to score.’ Lesson plan, Football unit, 25 September 2017. ‘Build a small dance choreography: with teacher-selected music, students are split across learning teams and are given 8 min to create and ‘tell’ a story through body expressions.’ Lesson plan, Dance unit, 11 October 2017.

In the initial phase, students were unable to use appropriate social skills for the development of precise and unambiguous communication, expressing themselves with authoritarianism and with difficulty accepting others’ opinions. Students were not able, as desired, to accept, support their colleagues, and resolve conflicts, particularly if these colleagues were not part of their personal role as friends. Cooperative work experiences were more positive/negative depending on the degree of proximity and friendship level and the students distinguished ‘cooperating’ from ‘trusting’ their colleague. ‘Alice: If that person [Emily] happened to be polite when speaking to me... not so much what she said, it was how she said it… Get there and think ‘hey, I’m here, I’m the boss’, not cool (…) some people do not like to be criticized by those around them, it might seem like an attack, but we’re actually trying to help them improve their skills. Thomas: Cooperating is one thing, trusting someone, a completely different thing. Trusting that she will do her job and give her best effort (...) with those who already were my ‘buddies’, ‘hey, heads up, that’s not the task’ (...) If I did not get along with that someone, I knew what they’re doing is wrong but I kept it to myself.’ 1st FG, December 2017.

However, NT’s more open approach, not fully measured through explicit strategies that promote ‘everyone’s mandatory’ participation (e.g., ‘Think-Pair-Share’ or ‘Jig Saw’) unintentionally led to not all the elements of the working groups contributing to the tasks. Tasks were assumed almost exclusively by the federated/experienced students who had more knowledge of the sport, while the rest of the group was playing a more passive role. If in some groups this issue was not problematic, because the contributions of each element were taken into account, other students were not yet able to share and accept the group’s ideas (i.e., lack of appropriate social skills and promotive face-to-face interaction). ‘Stephanie: Initially, we had a lot of different opinions, reaching consensus was ‘mission impossible’. The best players in a sport did not accept a different suggestion for a drill or a tactic, and when they accepted it, the communication was not really working. Either they went on, against their will, or simply did things differently from what was suggested.’ 1st FG, December 2017.

3.1.2. NTs’ Responsive Intervention: Stepping back to Provide More Structure

Through the constant process of reflection, the NT realized that she had a misconception of ‘equitable participation’ and that this had been conditioning the students’ contribution to the tasks. In other words, the tasks required a level of knowledge that some students did not have. The following excerpt clarifies the shift in NT’s conception of what ‘equitable participation’ should mean in the specific context of a CL approach: ‘Looking back, when the year started, I thought everyone had to take an active role and participate in all tasks in the exact same way. Is that not what CL is supposed to be? Now, I see it differently. Wanting all students to do exactly the same thing, assume the same level of responsibility, is it realistic? Am I really taking their individual needs into account when I present them with a task that is still too far out of their ability in that moment? Maybe finding ‘the right man or woman for each job’ is the way of meeting CL. The most knowledgeable players in a sport might have a stronger role in a given task in that unit [they can, for example, design their own specific learning tasks]. Can the other students not also play an important role, but at a different level? [perhaps, making them responsible for more generic learning tasks, like, leading the physical condition drills]?’ Field diary, 22 November 2017.

Besides that, given the existing relationships among students and their way of working (i.e., authoritarian and ambiguous communication, difficulty in accepting other opinions, supporting colleagues and resolving conflicts), it was necessary to raise their awareness of the importance of cooperative work. This pedagogical intention was expressed in an attempt to provide them with specific tools to develop interpersonal skills, which included: (1) recourse to audiovisual media to promote debates focused on social justice and acceptance of difference (i.e., visualization of an episode of the Glee series that portrays the role of students with more and less abilities within a team that was playing in a regional championship), (2) external regulation, compulsory cooperation, negotiation, group discussion, and problem-solving activities (e.g., dance unit: build a class choreography that encompasses the ideas of all elements of the working groups; football unit: design specific fitness exercises; badminton unit: decide and lead the warm-up), and (3) creation of a culturally relevant context with significant activities for students (i.e., formal competition), which contributes to the creation of learning climates where not only the result of the game is valued, but also the values inherent in sport, such as fair play, justice, and good sports practice.

Nevertheless, the NT felt the need to control the teaching–learning process more tightly, giving more support and being more directive. At the same time, by intervening in situations that presented no mutual help/conflict, she took the risk of not being able to change the way students communicated with each other. The following excerpt from the field diary is an example of her intervention: ‘I noticed in one of the groups a student was struggling to keep the ball up and not a single teammate was helping her or providing any feedback (…) I approached the rest of the team: ‘she’s in trouble, no one will help her?’’ Field diary, 8 November 2017.

3.1.3. Follow-Up Student Responses: Seeing the First Light at the End of the Tunnel

At the end of the 1st AR-cycle, the students already had some appropriate social skills (e.g., adopted communication has often started to be more positive, like listening, sharing decision-making, and giving and receiving feedback). Although face-to-face interaction had not yet reached its fullness, it was characterized by the acceptance and appreciation of the perspective of colleagues, recognizing that it is worth making ‘sacrifices’ for the good of the team. Students were made aware of their attitudes (good and bad) and the need to change behaviors, partly due to: (1) group processing sessions and (2) the use of formal competition (i.e., tournaments). In these, the expansion of the valued competences allowed for an increase in the commitment in the classroom, the mutual help within the team and the sense of justice. ‘Amanda: If we approached someone, like, ‘listen up, you’re not doing anything right’. Instead, if we go like, ‘look, you’re not doing this as it is supposed to be, can you try to put your arm like this, or hit the ball like that’, genuinely trying to help, it makes all the difference... Patrick: The lesson dynamic was different… She [Anna] was like: ‘come on Patrick, come on, come on’. I was surprised [with Anna’s change]. She even came up with this idea of everyone in the team using the same t-shirt color. Additionally, we got awards for the team-work goals we achieved [laughs]. First, I was like ‘how corny, I’m not taking any awards from you Miss. This is not for me’. However, then I was ‘forced’ to accept it. Four votes saying I should be awarded, it was actually cool.’ 1st FG, December 2017.

For the students, although the teacher was young and was at the beginning of her teaching career, she had the ability to understand that they learn in different ways and gave them more freedom to act (i.e., teacher as a facilitator of learning) and feel ‘powerful’ within the class. The students emphasized the constant cooperative work they had to do and the opportunity to take on roles besides the player, which helped them to create some closeness among them. Contrary to what happened at the beginning of the year, when they let personal problems interfere with the work, now they were able to separate work from relationships. ‘Amanda: There are young teachers who are already very strict and are fully aware of what they want from PE, what to take from each student... everything is the same for everyone (...) you (Miss) are not like that (...) you know some students have specific difficulties and will need overcome them in different ways. Thomas: We have this responsibility that you (Miss) gave us (...) even though we do not have a voice in the main planning of the lesson’s games, it had an impact, because we were being called on to teach the warm-up drills to our teammates. Stephanie: Perhaps, in some teams they did not get along with one another. However, as the time went by we actually had to talk to each other and to find ways to function as a team, and we became more bonded to one another. We had no alternative, we needed to cooperate.’ 1st FG, December 2017.

3.1.4. Unachieved Outcomes

Although students started showing signs of recognizing the educational value of CL and provided more feedback to their colleagues, they did not trust or accept everyone and continued not to be positively interdependent with each other, as individual success was more important than the collective. Aggressive communication, which translated into the use of a high tone of voice that quickly evolved into a discussion, still occurred occasionally, particularly when a colleague, but not a friend, had a different opinion, or did not understand why something was done or made mistakes, thus hindering the group.

3.2. 2nd AR-cycle [January 2018–March 2018]—Accepting Cooperative Learning

3.2.1. NTs’ Responsive Intervention: Sharing Responsibility to Both Mediate and Enhance the Students’ Active Role

One of the major goals on the 2nd AR-cycle included the sharing of responsibility with the learners to conduct the learning activities, offering them a more active role within the PE class. Moreover, and due to the need to maximize the students’ social skills and cooperative relations, the development of positive interdependence was crucial.

In addition to the strategies implemented by the NT in the previous cycle, three great tools were added: (1) assignment of responsibilities of different kinds (i.e., responsibility for designing and implementing tactical exercises in their home groups; decision-making responsibilities and logistical tasks responsibilities); (2) students’ participation in a federated training context, so that they could experience the way athletes establish relationships and communicate with each other; and (3) multiple sessions of group processing and promotive face-to-face interaction.

It is important to note that the sharing of responsibilities was only possible due to the evolution in the way students worked during the previous cycle. If they had not been receptive to CL in the focus group sessions, they had not reinforced the idea that their commitment in the classroom had increased. Due in part to the allocated space of action, perhaps this sharing would not have been viable. ‘Vivian: We asked ourselves when it started ‘what is happening here? a teacher who wants us to become autonomous?’. Alice: The lessons are much more productive (…) it’s a different dynamic (…) instead of explaining everything, you also put the students, those who are supposed to be better, explaining it to us. It involves more cooperation. Anna: During these 11 years I hated Physical Education, so I think this is the only year that I have really enjoyed it (…) it’s like a miracle!’ 2nd FG, March 2018.

3.2.2. Follow Up Responses: Finally Getting It—‘I Cannot Succeed unless We all Succeed’

The implemented strategies triggered a change in the students’ way of thinking and being. They highlighted as effective strategies: (1) the participation in the federated training context; (2) the fact that the teacher shared with the students the decision-making power for the constitution of the work groups, but took the final decision (i.e., to balance the power exercised and the power attributed to the students). If not, there was a risk of students always choosing their friends and the barrier of lack of trust and unity would never be broken; and (3) multiple sessions of group processing and promotive face-to-face interaction (i.e., students need to share their opinions with colleagues and suggest solutions to the identified game problems). ‘Harry: They [federated athletes] they did not know us anywhere but they ‘scolded us’ [laughs] we could tell they wanted to help us improve. Stephanie: It was possible to transport [this social learning] to the class. Amelia: I do not feel intimate with half of the people in our class, but now I feel I can say ‘wait a minute, this is not right’ or ‘that’s wonderful, well done’, or take it well when someone comes along saying the same to me.’ 2nd FG, March 2018.

The applied strategies helped students to understand that the aggressive communication existing in the previous cycle did not benefit the achievement of their goals. It was necessary to build ways of communicating that were accepted by all (i.e., use of appropriate social skills). In the final phase of the volleyball instructional unit, which coincided with the end of the 2nd AR-cycle, students began to realize that success was only possible if all members of the group were successful. To do this, they had to help each other carry out the tasks (Table 1). More important than the result—win/lose—the feeling of victory was only authentic when the result had the contribution of all the elements (i.e., positive interdependence). The development of closer relationships was evident and regardless of friendships they felt free and wanted to communicate and help all colleagues. ‘Anderson: [We develop] the ability to teach things to other people, to communicate with others, to express more clearly the ideas we wanted to explain. Elis: We started to feel closer to each other because we stopped being so selective [with people] and act as a whole. Richard: Even today [in the PE lesson], my group was me, Harry, and Amelia, and sometimes there were just plays between me and Harry and we could even make a point, but it was ‘ok, we made a point’, I was a little indifferent. However, when she also interacted in the play, I was happy and motivated (…) [there is success] when everyone works together (…) achieving the goal is not enough, it is absolutely necessary to work together.’ 2nd FG, March 2018.

The NT’s intervention during the 2nd AR-cycle allowed her to stop being the only source of knowledge and helped the students, who could use their own colleagues to solve the obstacles arising from the practice. When asked if the teaching and learning process was shared with them, and what they thought of the responsibilities assigned to them, the students were clear in their opinions: ‘Anthony: The teaching process is being shared. Particularly now because we are definitely part of the teaching (…) now we are more skillful in understanding the tactics, some people have more ability to position correctly in the court, other students are understanding the game better, we can help each other and try to teach each other how things can be done. Stephanie: [The dynamic of the lesson activities] assign us greater responsibility. It makes us also know how to make decisions, to choose between this or that, which later [outside PE] will be useful to us.’ 2nd FG, March 2018.

3.2.3. Unachieved Cooperative Learning Outcomes

During the 2nd AR intervention students showed great improvements in the ability to learn together. They developed closer, trusting, and unified relationships; a form of communication accepted by all; mutual help in carrying out tasks, regardless of the degree of proximity to colleagues; and positive interdependence. However, it was possible to note that the responsibility assumed by them within the class still occurred in relatively simple tasks. It was necessary, now that cooperative work was taking place, to extend the level of responsibility assumed in learning activities toward greater cognitive and social implications.

3.3. 3rd AR-Cycle [April 2018–June 2018]—Embracing Authentic Personal Commitment to Cooperative Learning

3.3.1. NTs’ Responsive Intervention: Reaching the Ultimate level—Understanding the Internal Properties of CL

Until now, students had assumed responsibility for isolated tasks and simplified content. However, with most of the cooperative work problems resolved, the teacher was able to take the next step and maximize students’ learning from CL dynamics. The main strategies implemented were: (1) hold students accountable for fundamental aspects of PE, such as content development, task selection, technical and tactical decision-making, peer feedback, instructional leadership and class management; and (2) challenge students to understand CL internal structures, such as positive interdependence, appropriate social skills, promotive face-to-face interaction, individual accountability and group processing, and transform them into learning situations appropriate to PE. The following excerpt reflects one of these moments: ‘My best option (…) is to assign them a key element of CL (positive interdependence, individual accountability, etc.); and, together, build various learning situations that promote the key element and ‘take over’ 14 min of the lesson, from instruction, to performance and monitoring of the other students’ motor activity.’ Field diary, 30 May 2018.

3.3.2. Follow Up Responses: A Long and Pleasant Journey

At the end of the 3rd AR-cycle, students agreed that the relationships that existed at the beginning of the year had been an obstacle to cooperative learning, making the decision-making, reconciling different opinions, and overcoming the challenges proposed by the NT hard. Students highlight as effective strategies for their resolution: (1) the use of activities that necessarily required cooperation for success to be achieved; and (2) teacher active mediation at certain times of the year (e.g., stand firm in the face of the first conflicts, forcing students to remain in their working groups). ‘Amelia: In the beginning, in the dance unit, it was more difficult [to make decisions]. Having to set up the choreographies was complicated. Now it would have worked much better as our relationship with each other evolved (...) we got used to ‘we have to work with other people’ and we ended up seeing that maybe that person was not what we thought she was. If we were allowed to select [the teams members] every time, without that special arrangement you [Miss] tried to do, we would likely choose those within our group of personal friends.’ 3rd FG, June 2018.

Like at the end of the previous cycle, the students proved to be interdependent with each other. When asked what enabled this, they considered that it was due to (1) having been placed in situations that could only be solved with the contribution of all (e.g., create the class choreography in the dance unit); (2) various tournaments (i.e., football, badminton, volleyball and basketball); and (3) the volleyball instructional unit (a team sport in which it is essential that all players on the field cooperate to be successful). ‘Vivian: When we were playing football [1st AR cycle], Ellen and I were in a group of guys and the Miss said ‘the ball can only go on goal after passing’ and they had to leave that little pride behind them of ‘ah, they are weaker’ and passed the ball to us. The game went well, and it allowed us to actually play the game, not just, stand there, watching the game. Amelia: Mostly, due to the tournaments, because everybody wanted to win. Richard: [In volleyball] we depend a lot on other people.’ 3rd FG, June 2018.

The positive change in the way students established communication with each other was evident. They contributed to the discussions, knew how to listen, gave feedback to colleagues, talked about what was good or bad and what was necessary to change and had patience and understanding in the face of colleagues’ difficulties. Besides that, there was a feeling of collective goodness that was superior to the individual self, which encouraged and facilitated the individual effort in reaching the group’s goals (i.e., individual accountability). The idea that the socialization among the students allowed them to enjoy the established cooperative relationships was shared. ‘Bella: [Before] we were more focused on ourselves and we wanted to evolve ourselves. Now [there is] a greater concern for others. Amelia: In football [1st AR cycle] I was on the team with Thomas and he was a bit rude while teaching. Now in basketball [3rd cycle], I also teamed up with him (…) He knew that I might not know how to do something so well and he explained to me in another way instead of being rude.’ 3rd FG, June 2018.

According to the students’ perspective, it was essential that the transferring of responsibilities for the teaching and learning process had occurred gradually. In other words, students took on more simple tasks and responsibilities when their relationship was distant and conflicted, and as relationships became more cooperative, students were able to take on bigger tasks and responsibilities and a more active role in the classroom. In the students’ opinion, it is possible to share the teaching and learning process between teachers and students. Teacher’s role is to teach and facilitate the practice, and students work these teachings in the easiest way. There is not a unique way of learning and teaching. ‘Thomas: In the first classes the Miss had everything [exercises, learning teams’ constitution] ready for us and then, over time, you gave us tasks and we implemented them in class. We started to interact more. Having a role in class. Teacher: What if I had started to ask you for these things [more demanding learning tasks and responsibility] right from the beginning of the school year? Vivian: It was going to go badly [laughs]. As we did not have confidence with each other to say ‘look, I do not want you to do it like this’, ‘agree,’ or ‘I think it’s better another way’. Alice: We are not all alike, my way of learning is not the same as his or her way of learning, it is different. Richard: You did not teach everyone in the same way, it depended on each person’s individual needs.’ 3rd FG, June 2018.

As a final reflection, the NT asked herself about the feasibility of having given students this space—of the 3rd AR-cycle—earlier, concluding that, taking into account its characteristics and the students’, it would not have been possible. ‘[In the beginning] the group did not have working habits, did not know how to cooperate, they were not used too thinking, having an opinion, having to decide, participating, choosing (…) I can say they were used to doing what the teachers tell them (…) What about me? A teacher at the beginning of career who is learning not only how to teach, but the best way to do it and that promotes student development at all levels and includes them in the teaching process. Therefore, my answer is ‘no, it would not be possible (…) but it is possible to do it now.’’ Field diary, 30 May 2018.

4. Discussion

This study examined how a novice PE teacher implemented the CL model and shared with her students the responsibility for actively engaging with the teaching–learning process. In addition, this study examined the students’ point of view about how they lived and perceived the cooperative experiences and student-centered learning. Overall, the results showed that at the beginning of the year the NT misinterpreted the concept of ‘equitable participation’ (there was an unstructured transfer of responsibility to students) and was led to exercise greater ‘control’ and provide more guidance to students about how to handle that process. Conversely, at the end of the year, the NT understood that as a facilitator of learning, to assign students a central role in their learning experience, she had to use direct and indirect strategies, depending on students’ current and specific learning needs. In turn, students progressed from an initial starting point where they were just willing to help their teammates if they were also part of the cycle of friends and assumed few responsibilities in PE class to an end point where students were positively interdependent on each other in which there was a more pronounced sharing of the teaching–learning process between the NT and the students.

It should be noted that the transformation process, one that allowed the NT and her students to become increasingly skilled at teaching and learning within a new model was only possible due to the extension of the implementation of CL across several units [10,53]. This corroborates the findings of the study conducted by Fernandez-Rio et al. [53], where students’ perceptions after experiencing CL reflected positive ideas such as cooperation, relatedness, enjoyment, and novelty. Furthermore, students’ negative feelings, like disappointment or annoyance, were reverted after an extended period (30 lessons). Further, the AR and the immersion of the teacher-researcher in the real-life context of this study allowed the NT to continuously adjust procedures to the dynamic nature of the teaching–learning process leading to improved self-knowledge and understanding of such practices [35]. This finding aligns with the work of Casey, Dyson, and Campbell [11], where the teacher-researcher, through an AR project, was able to move from a center stage position to the ability to empower children’s decision-making processes.

Regarding the analysis of each intervention cycle, the 1st AR-cycle diagnosed the students’ cooperative limitations, essentially based on their lack of experience in cooperative work and poor social relatedness with their peers. Students struggled with ‘trusting’ their peers to provide feedback [26], were not always able to prevent personal problems from interfering with group work [54], ‘clashed’ with each other when they had different opinions and were authoritarian with the aim of imposing their individual ideas. Furthermore, several students appeared to be overly dependent on the leadership of their higher-skilled peers and assumed a passive role in the learning activities [12].

Two possible reasons may explain these findings. First, it was difficult for students being challenged with the introduction of a new pedagogical approach [10,11,12,26], reinforcing the idea that teachers need to be aware that some students may not spontaneously have a self-determined disposition conducive to inclusive behaviors [55]. Second, although it seems to be common ground at the beginning of a teacher career [26], the NT’s initial lack of pedagogical ability to adapt the teaching context to students’ individual needs (e.g., appropriately modifying games) may have contributed to the exaggerated reliance of the low-skilled students on their higher-skilled teammates’ support.

To act upon this issue, the constant teacher self-reflection process and genuine interest in students’ voices were critical aspects. This was also important in other research involving NTs, where the challenges faced in their practice were more easily resolved through reflections and dialogue with students [26]. Through this process, the NT became aware of her limitations and the identification of solutions that would meet the students’ needs. By doing so, students’ ability to cooperate, the development of appropriate social skills, and promotive face-to-face interaction [10] was increased via four main strategies: the design of practice tasks according to students’ level and knowledge and the differentiation of roles; the conditioning of the competition; the use of group processing sessions; and a more directive intervention.

Lesson by lesson, students showed more ability in their interpersonal skills [12] and, although they were not yet positively interdependent on each other, at the end of the 1st AR-cycle, the communication among students became more open and sincere. Students realized that everyone had their singular value and could contribute to the team goals, even when students were performing tasks in which they were not so comfortable. Instead of laying down and removing themselves from their role and from the activity [12], they supported their colleagues and helped them.

In addition to the strategies used by the NT, another possible reason may explain students’ cooperative behaviors at this phase. As the competition was the most motivating aspect of the lessons (probably because students were allowed to demonstrate their capabilities to the greatest extent possible and work hard to succeed in the team tournament) [56], and they enjoyed lessons, they socialized more productively with each other. In other words, the enjoyment that they felt during formal competition events may have increased their commitment to participate in the activities [57], promoting positive social relationships between students [11].

During the 2nd AR-cycle, the improvements found suggested that the NT considered that the students were showing a specific set of ‘minimal skills’ that allowed her to give them more space for active intervention in the lessons. Similarly, in a recent study conducted by Howley and O’Sullivan [58], the authors also concluded that the three NTs (four years of experience as PE teachers) had difficulty in relinquishing control, essentially based on students’ misbehaviors and for considering that ‘they [the students] were not ready for it’ (p. 6). In fact, for many students, taking responsible control of their own learning can be daunting, due to their previous teacher-centered experiences that have not prepared them for the level of cognitive, social, and personal responsibility required by student-centered approaches such as CL [59].

Keeping this in mind, during the 2nd AR-cycle, the NT shared with students some of her responsibilities, although these involved low complexity processes (e.g., logistical tasks responsibilities—see Results for more details). As opposed to ‘visiting consumers’ of the learning environment [60] transferring power to students requires teachers to recognize that students can become experts in their own learning [18]. Scholars have argued that democratic pedagogies in which students and teachers cooperate may improve the learning process in PE [61]. Indeed, it was interesting to find that in students’ opinion, the teacher’s combination of more directive and indirective strategies had been important to support them, and they enjoyed the sharing of responsibility with the NT. As in Guadalupe and Curtner-Smith [62], when teachers and students learn to negotiate, the relevance and experience of PE to students is increased. Therefore, as Wang and Liu [63] noted, CL should pay attention to the interaction between teachers and students, because the premise ‘constructive interaction between the learner and the educator’ is central within student-centered approaches [64].

Globally, students’ ability to cooperate during the 2nd AR-cycle was increased via the multiple situations in which consensus had to be reached [65], group processing sessions [10], and the experience of a sport club training context. Together, these strategies enabled students to realize that the ‘charging’ of the colleague could be done through constructive dialogue. The implemented strategies had demands at the level of co-responsibility, highlighting the importance of the collective to the detriment of the individual and forcing students to communicate properly while they carried out the tasks. Such constructive dialogue was evident in students’ ability to tell their colleagues what they think and feel, and praise and criticize them, in a way that was accepted by all. Students were able to express more clearly their ideas and act as a whole. Furthermore, and in congruence with previous research [62], where students initially hesitated to engage in the learning process with those who were not within their ‘circle of friends’, at the end of the second stage of the AR-intervention cycle students became positively predisposed to communicate and cooperate with all teammates for achieving common learning goals regardless of the level of friendship.

Students realized that there were more advantages if they all contributed to the same purpose instead of striving for individual goals and that the most important thing was not the result (winning) but everyone’s legitimate contribution for cooperative goal achievement. These improvements enhanced their interest for participating in the activities while making learning more rewarding through the sharing of experiences. This corroborates findings by Luo et al. [4], where CL promoted mutual sharing of knowledge and skills and, in turn, increases in self-determined cooperative behaviors among students.

In the 3rd AR-cycle, after the previously described problems related with students’ social interactions were solved, the NT assigned students even more decision-making power and a higher responsibility role [2] (i.e., concurrently design, manage, and implement learning activities). This result suggests that teachers need time and confidence to refine their practices and allow themselves to have more control over the teaching–learning process [58].

Contrary to what happened at the beginning of the school year (i.e., students helped each other for the purpose of winning the competition events), the end of the intervention program seemed to bring about increment in students’ positive disposition toward participation in the activities [53] and they recognized that differing skills of different teammates within the heterogeneous groups could aid their learning in different ways [17]. This finding is in line with the study conducted by Fernández-Río et al. [53], where the main goal was to investigate the impact of a sustained CL intervention on student motivation. After an extended time period (three consecutive units), students increased intrinsic motivation and had a greater perception of cooperation, relationships, and enjoyment.

In the current study, the use of CL afforded students more responsibility focused on the social aspect of learning and created a learning environment where cooperation was valued [2,13]. The goal was to work with and for each other [12] and the terms ‘solidarity’, ‘respect’, ‘human values’ and the feeling of belonging to the group strongly emerged [66] (p.6). Indeed, as Goodyear [54] stated, at the end of the intervention program most students commented on the ways in which they were now supporting each other’s learning and perceived that they had an increased level of responsibility and ownership of their learning. This finding shows that it takes some time for the students to truly learn how to learn and behave in a new model [23,67]. The same idea was presented in other studies [22] that suggest that learning the social skills necessary to complete the roles assigned in a student-centered model unit requires time [68]. Simultaneously, teachers also need time to adjust their teaching to a student-centered approach [69].

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

In conclusion, this study highlights that the use of SCMs by novice PE teachers can be hard at first but should be encouraged. CL is a complex model that needs time to be implemented effectively and to allow students to take advantage of its potential. From the results of this study, it can be seen that it is necessary to use several strategies and a constant adaptation of the teaching process to allow the development of personal and social skills, consequently granting students greater responsibilities and a more active role in PE class. The use of more direct and indirect support, balancing the power exercised by the teacher and the power and responsibility attributed to the students, being sensitive to each other’s ideas, working cooperatively, modifying the learning activities, giving students permission to perform different roles adjusted to their level of knowledge and skill, and encouraging students’ participation in authentic and meaningful learning tasks useful strategies.

The main contributions of this study are: (1) analysis of the beginning of a teacher’s career in a real practice context; (2) the opportunity to give students a voice regarding their learning–teaching process; (3) implementation of a longitudinal qualitative AR design; (4) the utilization of data collection from multiple different perspectives (teacher lesson plans, field diaries, and student focus-group interviews); (5) and the methodological triangulation. Nevertheless, this study is not without limitations. Seeking to minimize the risk for individual researcher bias in the interpretational analysis, it would have been beneficial to use an indirect observation system (e.g., recording of class images, teacher and student’s audio recording interventions, observation of classes by one of the members of the research team).

Institutions of education (e.g., schools, universities) need to review the training process for new professionals [70]. Based on the results of this study, we recommend that the structure of PETE school placements should be favored, with longer protocols and the cooperation of supportive and knowledgeable teachers [22]. This can allow the development of the teachers’ abilities to implement SCMs and better prepare them for the beginning of their careers, where external support does not exist. PETE should focus on the development of SCMs knowledge and demystify some of the misconceptions that are created around the teacher’s role as a facilitator of practice (e.g., a teacher who acts according to a student-centered approach cannot resort to directive teaching strategies). It would be beneficial to invest in the conceptual clarification of SCMs and focus on the teaching of the initial control process so that teachers feel more secure and gradually empower their students. We propose that future studies continue to focus on the professional development of NTs and the use of longer learning units with a focus on intervention (e.g., AR, participant research).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S., C.F. and I.M.; methodology, R.S. and I.M.; formal analysis, R.S.; investigation, R.S.; resources, R.S.; data curation, R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S.; writing—review and editing, R.S. and C.F.; visualization, C.F.; supervision, I.M.; project administration, I.M.; funding acquisition, R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT), grant number SFRH/BD/132947/2017.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Sport from the University of Porto (Process CEFADE 18.2019, approved on 27 July 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available for ethical reasons.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all the students for their participation in the present study and the school where the study took place.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Dyson, B.; Colby, R.; Barratt, M. The co-construction of cooperative learning in physical education with elementary classroom teachers. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2016, 35, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, B.; Griffin, L.; Hastie, P. Sport education, tactical games, and cooperative learning: Theoretical and pedagogical considerations. Quest 2004, 56, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Choi, E. The importance of indirect teaching behaviour and its educational effects in physical education. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2016, 21, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.-J.; Lin, M.-L.; Hsu, C.-H.; Liao, C.-C.; Kao, C.-C. The effects of team-game-tournaments application towards learning motivation and motor skills in college physical education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallati, C.; Bertazzi, J.d.A.; Schützer, K. Professional skills in the Product Development Process: The contribution of learning environments to professional skills in the Industry 4.0 scenario. Procedia CIRP 2019, 84, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, D.; Paredes-Velasco, M.; Chivite, C.; Fernández-Arias, P. The challenge of increasing the effectiveness of learning by using active methodologies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, T.; Kohl, H. Perspectives for international engineering education: Sustainable-oriented and transnational teaching and learning. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 21, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomer, J.; Cañabate, D.; Stanikūnienė, B.; Bubnys, R. Formulating modes of cooperative leaning for education for sustainable development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, A.; Goodyear, V. Can cooperative learning achieve the four learning outcomes of physical education? A review of literature. Quest 2015, 67, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dyson, B.; Casey, A. Cooperative Learning in Physical Education and Physical Activity: A Practical Introduction, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, A.; Dyson, B.; Campbell, A. Action research in physical education: Focusing beyond myself through cooperative learning. Educ. Action Res. 2009, 17, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Casey, A.; Goodyear, V.; Dyson, B. Model fidelity and students’ responses to an authenticated unit of cooperative learning. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2015, 34, 642–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goodyear, V.; Casey, A.; Kirk, D. Hiding behind the camera: Social learning within the Cooperative Learning Model to engage girls in physical education. Sport Educ. Soc. 2014, 19, 712–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson, D.; Johnson, F. Joining Together: Group Theory and Group Skills, 12th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Hernández, N.; Martos-García, D.; Soler, S.; Flintoff, A. Challenging gender relations in PE through cooperative learning and critical reflection. Sport Educ. Soc. 2018, 23, 812–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, D.; Quennerstedt, M. Power and group work in physical education: A foucauldian perspective. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2017, 23, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, N.; Barber, A.; Keane, H. Physical education undergraduate students’ perceptions of their learning using the jigsaw learning method. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2019, 25, 713–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennis, C. What goes around comes around... Or does it? Disrupting the cycle of traditional, sport-based physical education. Kinesiol. Rev. 2014, 3, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goodyear, V.; Dudley, D. ‘I’m a facilitator of learning!’ Understanding what teachers and students do within student-centered physical education models. Quest 2015, 67, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasri, N. Self-directed learning through the eyes of teacher educators. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2019, 40, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Burry-Stock, J.A.; Rovegno, I. Self-evaluation of expertise in teaching elementary physical education from constructivist perspectives. J. Person. Eval. Educ. 2000, 14, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.; Farias, C.; Mesquita, I. Challenges faced by preservice and novice teachers in implementing student-centred models: A systematic review. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, A. Models-based practice: Great white hope or white elephant? Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2014, 19, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bores-García, D.; Hortigüela-Alcalá, D.; Fernandez-Rio, F.; González-Calvo, G.; Barba-Martín, R. Research on cooperative learning in physical education. systematic review of the last five years. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2020, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañabate, D.; Serra, T.; Bubnys, R.; Colomer, J. Pre-service teachers’ reflections on cooperative learning: Instructional Approaches and identity construction. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bodsworth, H.; Goodyear, V. Barriers and facilitators to using digital technologies in the Cooperative Learning model in physical education. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2017, 22, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legrain, P.; Escalié, G.; Lafont, L.; Chaliès, S. Cooperative learning: A relevant instructional model for physical education pre-service teacher training? Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2019, 24, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, N.; Alonzo, D.; Nguyen, H. Elements of a quality pre-service teacher mentor: A literature review. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2020, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.R.; Marttinen, R.; Mercier, K.; Gibbone, A. Middle school students’ perceptions of physical education: A qualitative look. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2021, 40, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, D.; Serriere, S.; Stoicovy, D. The role of leaders in enabling student voice. Manag. Educ. 2012, 26, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mockler, N.; Groundwater-Smith, S. Engaging with Student Voice in Research, Education and Community: Beyond Legitimation and Guardianship; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Weed, M. Research quality considerations for grounded theory research in sport & exercise psychology. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, P.; Ribeiro, J.; da Silva, S.M.; Fonseca, A.M.; Mesquita, I. The influence of parents, coaches, and peers in the long-term development of highly skilled and less skilled volleyball players. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carless, D.; Douglas, K. Stories of success: Cultural narratives and personal stories of elite and professional athletes. Reflective Pract. 2012, 13, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farias, C.; Mesquita, I.; Hastie, P.; O’Donovan, T. Mediating peer teaching for learning games: An action research intervention across three consecutive sport education seasons. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2018, 89, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ax, J.; Ponte, P.; Brouwer, N. Action research in initial teacher education: An explorative study. Educ. Action Res. 2008, 16, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. What is good action research? Action Res. 2010, 8, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemmis, S.; McTaggart, R.; Nixon, R. The Action Research Planner; Springer: Singapore, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, T.; Chróinín, D.; O’Sullivan, M.; Beni, S. Pre-service teachers articulating their learning about meaningful physical education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2020, 26, 885–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hordvik, M.; MacPhail, A.; Ronglan, L.T. Negotiating the complexity of teaching: A rhizomatic consideration of pre-service teachers’ school placement experiences. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2019, 24, 447–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guzmán, J.F.; Payá, E. Direct instruction vs. cooperative learning in physical education: Effects on student learning, behaviors, and subjective experience. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods, 4th ed.; SAGE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Goss, H.R.; Shearer, C.; Knowles, Z.R.; Boddy, L.M.; Durden-Myers, E.J.; Foweather, L. Stakeholder perceptions of physical literacy assessment in primary school children. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilgun, J. Enduring themes in qualitative family psychology. J. Fam. Psychol. 2014, 19, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffe, H. Thematic analysis. In Qualitative Research Methods in Mental Health and Psychotherapy: A Guide for Students and Practitioners; Harper, D., Thompson, A., Eds.; WileyBlackwell: Chichester, UK, 2012; pp. 209–223. [Google Scholar]

- Coghlan, D. Insider action research: Opportunities and challenges. Manag. Res. News 2007, 30, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guba, E.; Lincoln, Y. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N., Lincoln, Y., Eds.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 1994; pp. 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N. Triangulation. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2012, 6, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, K. Enhancing Coaches’ Experiental Learning through ’Communities of Practice’ (Lave & Wenger, 1991). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Wales Institute, Cardiff, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Rio, J.; Sanz, N.; Fernandez-Cando, J.; Santos, L. Impact of a sustained Cooperative Learning intervention on student motivation. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2017, 22, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodyear, V. Sustained professional development on cooperative learning: Impact on six teachers’ practices and students’ learning. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2017, 88, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Morgan, K. Applying mastery target structures to cooperative learning in physical education. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2019, 90, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadrah, N.; Tolla, I.; Ali, M.; Muris, M. The effect of cooperative learning model of teams games tournament (TGT) and students’ motivation toward physics learning outcome. Int. Educ. Stud. 2017, 10, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chiva-Bartoll, Ó.; Salvador-García, C.; Ruiz-Montero, P.J. Teaching games for understanding and cooperative learning: Can their hybridization increase motivational climate among physical education students? Croat. J. Educ. 2018, 20, 561–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howley, D.; O’Sullivan, M. ‘You’re not going to get it right every time: Teachers’ perspectives on giving voice to students in physical education. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2021, 40, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, C.; Lyon, H.; Tausch, R. On Becoming an Effective Teacher: Person-Centered Teaching, Psychology, Philosophy, and Dialogues; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, C.; Freiberg, J. Freedom to Learn, 3rd ed.; Macmillan College: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, K.L.; Kirk, D. Girls, Gender and Physical Education: An Activist Approach; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Guadalupe, T.; Curtner-Smith, M.D. ’It’s nice to have choices:’ Influence of purposefully negotiating the curriculum on the students in one mixed-gender middle school class and their teacher. Sport Educ. Soc. 2020, 25, 904–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Y. Cooperative learning method in physical education teaching based on multiple intelligence theory. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2018, 18, 2176–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attard, A.; Lorio, E.D.; Geven, K.; Santa, R. Student-Centred Learning: Tool Kit for Students, Staff and Higher Education Institutions; European Students’ Union: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dyson, B.; Rubin, A. Implementing cooperative learning in elementary physical education. JOPERD: J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2003, 74, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hortigüela-Alcalá, D.; Hernando-Garijo, A.; Pérez-Pueyo, Á.; Fernández-Río, J. Cooperative learning and students’ motivation, social interactions and attitudes: Perspectives from two different educational stages. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goodyear, V.A.; Casey, A. Innovation with change: Developing a community of practice to help teachers move beyond the ‘honeymoon’ of pedagogical renovation. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2015, 20, 186–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ward, P.; Lee, M.A. Peer-assisted learning in physical education: A review of theory and research. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2005, 24, 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.; Farias, C.; Arroyo, M.P.; Mesquita, I. Modelos centrados en el alumno en Educación Física: Pautas pedagógicas y tendencias de investigación. Retos 2021, 42, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, J.M.; Oliveira, A.C.A.d.; Santos, A. Analyzing how university is preparing engineering students for Industry 4.0. In Transdisciplinary Engineering for Complex Socio-Technical Systems—Real-Life Applications, Proceedings of the 27th ISTE International Conference on Transdisciplinary Engineering, Warsaw, Poland, 1–10 July 2020; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).