1. Introduction

Local governments (also referred to as municipalities and councils) exist internationally as public administrators of towns, cities and regions. There has been a wide range of research undertaken in relation to the role of local governments in supporting inclusion within their communities. The fact that local governments are embedded within local communities means that they have a deeper understanding and knowledge of the unique communities they govern and are well placed to lead the public policy drive toward social inclusion [

1]. Researchers have investigated the role of local governments as the drivers of more diverse and inclusive communities across the globe and across a range of policy areas and population groups, including refugee migrants [

2], sexuality and intersectionality [

3], older people [

4], workforce inclusion [

5] and people with a disability [

6,

7]. This research paper focuses on local governments with respect to disability inclusion, specifically the inclusion of people with an intellectual disability.

Local governments are assigned a range of roles and responsibilities that differ depending on the country. The United Nations Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), which has been ratified by Australia, sets out the fundamental human rights of people with disability. The purpose of the CRPD is to “promote, protect and ensure the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms by all persons with disabilities”. Internationally, the relationship between local government and disability rights law and policy has a rich and complex history [

8,

9,

10]. This paper focuses on the Australian setting of local government and disability rights, which are framed specifically in this study as a right to inclusion and access to services, social and community events and public spaces, buildings and amenities. The Australian Disability Discrimination Act [

11] requires local governments to make their services accessible to people with disabilities. Very little research has been undertaken to explore how what constitutes accessible services may differ for people with different types of disabilities. This project was developed as a result of research that indicated that while local governments are relatively confident in providing accessible information to people with mobility, vision and hearing impairments, they are less confident about how to deliver information and to support the inclusion of people living with an intellectual disability [

12]. A systemic lack of accessible information, including how to access services and events, is widely recognised as a major cause of isolation in the community for people with intellectual disabilities [

13,

14,

15,

16].

Inclusion and social sustainability at a city scale were conceptualised and applied on a global scale with the introduction of the Age-friendly City Guide [

17]. This established a framework that has been adapted to address the inclusion of people with disabilities on an urban scale [

18]. In this study, we map the analysed data to the seven underpinning principles outlined in the original and adapted WHO cities frameworks. The authors recognise that people with intellectual disabilities are rarely consulted about their experiences of inclusion on a city scale and this research articulates how domains, including the physical, built environment and transport, and social and economic factors, influence the way people with intellectual disabilities experience a city.

The research team, which included people with intellectual disabilities as core members and co-facilitators, conducted focus groups with people with intellectual disabilities in a range of local government areas in Australia. The focus groups were designed to explore the concerns, preferences and priorities of people with intellectual disabilities in their local communities. This study is ultimately interested in contributing to an understanding of what constitutes an inclusive city for people with intellectual disabilities, which is one that provides the structures and services required to ensure an equitable and positive experience as contributing members of the community.

This research study forms part of a wider project designed to enhance the capacity of local governments in Australia to include people with intellectual disabilities in all aspects of citizen life within their Local Government Area (LGA). The study was designed to demonstrate to local governments the value of engaging with and listening to local people with intellectual disabilities. This investigation contributes to an understanding of social sustainability that recognises the participation and reflects the expectations of people with intellectual disabilities. This is timely and relevant given the global recognition that people with disabilities continue to be disadvantaged regarding sustainable development goals and that persons with intellectual and psychosocial disabilities are even more disadvantaged [

19].

2. Materials and Methods

The current study was designed to understand how people with intellectual disabilities perceive their local government and what places, services and qualities they value or want to change in their local community. This research was designed to reflect an inclusive approach and one that values lived experience and recognises this as an expertise.

Sharing some of the details of our methodology provides further insight into how inclusive practices are undertaken in a research environment and how they may differ from what is expected or what is usual practice. For this reason, we have provided more detail than is perhaps usual when explaining our inclusive methods and processes in undertaking focus groups with people with intellectual disabilities.

Our core team was diverse and was comprised of experienced researchers, disability advocates and people with intellectual disabilities. This structure ensured that lived experience was represented across all research activities and in all stages of the project. Recruiting, preparing for and facilitating focus groups by and with people with intellectual disabilities required attention to be given to the design of all communication materials, as well as the structure and the delivery of the focus groups.

Qualitative research methods were employed as the primary means of collecting and analysing data. Focus groups were considered to be the preferred data collection method for this study, as there is evidence that they offer research participants with intellectual disabilities an opportunity to build confidence through the involvement, peer support and validation of their views [

20]. This methodology has also been applied in a number of other studies that sought the perspectives of people with intellectual disabilities [

16,

21,

22,

23].

Focus groups were conducted in a selection of LGAs classified as being located in either major cities or regional areas, according to the Australian Standard Geographical Classification [

24]. Each LGA was chosen based on a balanced mix of metropolitan versus regional locations, in combination with established access of people with intellectual disabilities to local networks via advocacy and service organisations. All participants had lived experience of intellectual disability and resided in the local area where the focus groups were conducted. The participants were given the option of either participating in a one-to-one interview or a focus group and all participants, except for two, chose a focus group. All focus group discussions were recorded and transcribed. The transcriptions were de-identified in order to remove any identifying comments or names. The Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Technology Australia approved the study (ETH018-2713).

2.1. Aim

The aim of this research was to develop awareness of the inclusion needs and preferences of people with intellectual disabilities as they relate to participating in social and civic life and accessing amenities in their local area. The results were analysed through the lens of an adapted framework of inclusive cities based on the framework developed in [

18].

2.2. Research Questions

This study sought the perspectives of people with intellectual disabilities on their local community, with a focus on local government services, public places and personal experiences in the local community. The research was driven by the following research questions:

What do people with intellectual disabilities know about local governments and what they are responsible for?

What types of local places or services and facilities are utilised and valued by people with intellectual disabilities in their local area?

How do people with intellectual disabilities experience the range of services and facilities offered by their local government?

What types of improvements to local services and places do people with intellectual disabilities want to see?

In addition to reporting on the results of the research, this paper also acts as a demonstration of an inclusive research protocol. We recorded our inclusive approach in order to provide researchers and community engagement officers with practical detail on how we conducted inclusive focus groups. The paper is therefore also intended to contribute to the existing evidence of how to conduct focus groups and interviews that are inclusive of people with diverse disability types, particularly people with intellectual disabilities [

25,

26,

27].

2.3. Recruitment

Nine focus groups were conducted with people with intellectual disabilities from six different Local Government Areas (LGAs) across two states of Australia (New South Wales and Victoria). LGAs were selected based on a mix of regional and rural LGA locations balanced with the ability to have access to intellectual disability advocacy services in order to support the recruitment of the focus group participants. Recruitment was made possible via the coordination and networks of local advocacy or community groups, including the Council for Intellectual Disability (CID) and St. George and Sutherland Community College (SGSCC) in NSW. Staff members in each organisation contacted potential participants, who were all adults with intellectual disabilities residing in the selected LGAs where the focus groups were taking place. Staff provided participants with project information in printed and email formats and verbally explained the project to them. Agreement to participate was accompanied with written consent forms from each participant.

2.4. Participants

A total of 45 people participated in the research study in 9 separate focus groups and 2 one-on-one interviews were also conducted. Focus group attendance varied from 1 to 8 participants on a single day. Of the 45 participants, 21 identified as male and 24 as female. The age of the participants ranged from 19 to 52 years, with the median age being 34 years. There were no age requirements for inclusion in the study. All participants resided in the LGA that hosted the focus group they attended, in either a supported accommodation setting, such as a group home, or with parents in the family home. Everyone with an intellectual disability was welcome with no limitations or boundaries set on communication requirements, such as whether they needed to be verbal or non-verbal. Of the 45 participants, 43 communicated verbally and 2 participants used alternative communication methods to contribute to the discussions, accompanied by a known support person.

2.5. Data Collection

Each focus group was co-facilitated by a project team member and representatives from an advocacy organisation. Due to the locally recruited networks of participants in each LGA, the majority of participants were known to each other in each focus group and they also knew at least one of the facilitators. The venues of the focus groups were organised by local contacts. They varied in size and type: community halls, council chambers, public libraries, local clubs, local community colleges and advocacy organisation board rooms.

The focus group began with a short introduction and welcome, followed by a confirmation of understanding of what participation and consent meant for the participants. Everyone was advised that, if at any point they wanted to leave or stop their participation, they could do so without any consequence. This was explained verbally in easily understandable English terms so that participants knew that leaving the focus group would not cause anyone to be upset or disappointed. Signed consent was obtained from each participant. Anonymity and confidentiality were also emphasised to all participants.

To help make people more comfortable with sharing and participating in the group discussion, everyone present, including facilitators, note-takers, participants and any support people, took part in a group “ice breaker” activity at the beginning of each focus group, as has been done in previous studies [

16]. This was then followed by a collaborative group agreement where the group all contributed to a list of expected behaviours and guidelines of how the group should handle discussions or any issues raised. This was written on butcher paper and was visible in the room for the duration of the focus group discussion. Group agreement is a useful tool to navigate the power dynamics within groups and to make clear what participants need from each other and the facilitator in order to participate [

28].

After the introduction, ice breaker and group agreement had been completed, the facilitators encouraged a discussion around three main aspects of their local community. First, facilitators asked the group about the local area where they lived, things people liked to do and places they liked to go. Secondly, facilitators then asked questions about the role of local government and whether participants knew what their local government did. Facilitators also shared photos of the local council chambers and council-run locations, such as libraries, parks and local pools. Thirdly, the discussion was directed toward what inclusion means for people with intellectual disabilities. The groups were also asked the question “What would you do if you were the boss of your local government?” in order to find out what participants would change for the better if given the chance. By asking participants to think of themselves as the boss in this scenario, the participants could talk about what was important to them and what they would like to reinforce or change, but they did not have to consider constraints such as budget limitations or a lack of power. This question resulted in keen discussion and engagement in the focus groups.

Table 1 below outlines a framework applied to the inclusive focus groups, including introductory activities and semi-structured questions.

2.6. Data Analysis

Applying a general thematic analysis approach, the data were first coded by two authors through relistening and closely reading the transcripts from the focus groups. Quotes were extracted and discussed with the research team and were clustered into themes based on similar experiences, topics and activities discussed in the focus groups. Following this, we facilitated a discussion group of community researchers with intellectual disabilities. This was held to further explore the themes and codes via the quotations.

The perspectives and opinions of participants are presented according to a themed narrative discussion that is based on the inclusion domains in the Disability and Age-friendly Cities framework [

18]. This framework was founded by the WHO Global Age-friendly Cities Guide [

17], which provides a high-level mapping of domains by which inclusion in cities/communities can be addressed. The WHO framework is relevant to this study for two reasons:

It considers the city/community experience from the perspective of inclusion;

The WHO framework relates directly to cities/municipalities and local governments and their policies, services and infrastructure design.

Internationally, municipal councils/local governments have been applying these frameworks as a guide to their diversity policies and strategies [

29,

30,

31].

3. Results

The focus groups covered broad topics about recreation, public space and community attitudes. The participants expressed wide-ranging views about what is important to them in the community and what they want to change. There were distinct themes that emerged about what aspects of inclusion in the community were valued by people with intellectual disabilities. The responses were clustered into topic areas that were drawn from a framework of inclusive cities [

18] and have been applied to local government policy and governance strategy internationally:

Outdoor spaces and buildings;

Transportation;

Housing;

Social participation;

Respect and social inclusion;

Civic participation and employment;

Communication and information;

Community and health services.

3.1. Outdoor Spaces and Buildings

Outdoor spaces and buildings came up repeatedly in the focus groups. The participants expressed a wide variety of their favourite places to go in their local communities, from the shops to the pool and local parks. Many social activities were also discussed, including going to sporting events, bowling, dancing and organised social groups:

“I like to go and try different foods.”

“I feed the ducks in the community garden.”

“I go shopping and Westfields [local shopping centre/mall] to see people I know.”

“I like to go to my local coffee shop.”

“I like going to the stadium [football]. If it is noisy, we go home or have a break.”

“I feel comfortable near the shops outside Coles [supermarket].”

The focus groups revealed that many places in the local community were not considered to be physically accessible for people. Some pathways were too steep, some lifts were too small for people who use a wheelchair, buttons at crossing areas were too high and too hard to press and the crossings were unsafe.

Issues of inaccessible wayfinding and navigation were raised numerous times across multiple focus groups. Some found maps difficult to read. The design of signs also came up with participants commenting that they felt that, in their local community, signs were sometimes not where they should be, were unclear or did not make sense.

“In [the shopping centre] they have a touchscreen directory and it is so helpful—they should have those in the community.”

“There needs to be more information on how to get to the beach and accessibility. This information is not well known.”

“I don’t read maps with lots of words … so think about other ways [to help me know where I am].”

A lack of maintenance contributed to this lack of accessibility and safety, with discussions arising about lifts that did not work in town centres and roads that were poorly maintained. There was a recurring issue across both metropolitan and regional areas of public toilets, especially in public parks, being very dirty and run down. This contributed to people with intellectual disabilities feeling unsafe from both a hygiene and personal safety point of view.

“The toilets were closed because they got so [dirty/unsafe] …… I don’t go to that park now though.”

It was revealed in one focus group that a participant was aware of the existence of council chambers, not because it housed local government, but because it was the only location in the town centre with clean public toilets.

“I don’t trust the council toilets in the park.”

“We need more public toilets because when we are out in a group someone always needs to go … it is hard for our support people to find them.”

“I don’t go to the park sometimes because the toilets don’t always have toilet paper and soap.”

“I hate going to dirty, dark toilets but I have to sometimes because that is all there is.”

In a number of focus groups, the issue of unsafe pedestrian crossings arose, including the fact that there is not always enough time to cross the road safely.

“The council should fix our crossing, they go too fast, someone nearly got hit last week.”

“The crossing light changes too fast while I am still in the middle of the road.”

Parks were mentioned as being a place where councils had to remove weeds and had to keep the grass mowed, but were also discussed as being inaccessible, unsafe or too hot:

“The park gets too hot [in summer].”

“I don’t go [to that park], that’s not a nice place at night.”

“Parks should be kept clean and safe.”

An important aspect of the participants’ experiences in their local community was being able to attend local events, which were things that they felt were fun and were where they felt included.

“I like going to the shops and meeting friends.”

“The local Spring fair … I go every year … it is good.”

However, a number of suggestions were made about the importance of quiet places, for example at noisy sports events. While they like being able to be there and participate, the noise could become overwhelming and they need a break. This highlights the importance of considering sensory processing in outdoor spaces and public buildings. The importance of sensory-aware environments arose in other focus groups. In one, a participant explained that the mirrors and clear glass reflections around a new library staircase meant that she did not want to enter the building. In another example, a participant stated that they never use lifts because they make them feel uncomfortable.

Another issued raised was the need for more accessible parking spaces. This came up for two reasons: Firstly, people wanted accessible drop-off locations at public transport locations, events and other public spaces:

“We need more accessible drop-offs right at the library [and pool] … we have to walk too far and get tired as a group. It caused a problem before because we were always late to the class.”

Secondly, in three focus groups, the participants raised the problem of a lack of access to accessible parking spaces for the community transport vans that those who lived in a group home setting would regularly travel in to go to events and classes. The issue was raised that the vans were wheelchair accessible, but they did not fit under the low rooves of underground car park stations that are attached to public buildings, such as the library and pools. A consequence of this was that the bus had to park a considerable way from the desired location, which was extremely difficult for both passengers and staff.

The built environment was regularly referred to in the context of social inclusion, feeling safe and connecting to the community. Having “nowhere to go to feel safe” was discussed, particularly when feeling threatened or lonely. For participants, safe and enjoyable places were ones where “I go to meet people I know [at the café].” Feeling lost and alone, despite there being people around, was something that many in the focus groups could relate to, leading to appropriate wayfinding for individual preferences for navigating arising in the discussions (as discussed earlier).

3.2. Transportation

During the focus groups, it was explained that transport is not the responsibility of the local government (in Australia, it is the State government’s responsibility). Local governments in Australia are responsible for the management and funding of the local road network, but not the public transport systems and networks. Despite this, for participants in all focus groups, transport was a theme that repeatedly arose in discussions.

The participants expressed that they cannot travel easily due to limited public transport options. In regional areas in particular, participants expressed that it was difficult to “get out and about” in the evening and on weekends. Most of the participants who took part in the focus groups did not have access to a car and were reliant on public transport and taxis. The participants told us that public buses did not run in the evenings and ran infrequently on weekends:

“If I miss a bus, I have to wait for an hour … it is worse on a Sunday.”

In some of the focus groups, it was explained to the facilitators that taxis were too expensive and in more remote areas, there were not enough to go around. In some focus groups, people were unaware of Uber. All these issues made it difficult to get around.

Public transport also came up as a location where participants were likely to feel unsafe:

“I got yelled at on the train. I had nowhere to go to feel safe and there was no one to help …”

The participants highlighted the importance of transportation and issues surrounding safety and respect on public transport. Local governments in Australia are not responsible for public transport but could take the opportunity to advocate for change on behalf of people with intellectual disabilities.

3.3. Housing

Housing is one of the topic areas listed in Yeh’s framework of inclusive cities, however, is outside of the responsibilities of local government in Australia and therefore was not specifically raised as a topic for discussion in this study. Despite this, the participants would regularly bring up stories about where they lived and who they lived with. The participants lived in a range of settings, including group homes and with family members. Their pets and their care and provision were identified as an important element of their well-being.

3.4. Social Participation

In this context, social participation refers to the engagement of people with intellectual disabilities in recreation, socialising and cultural, educational and spiritual activities. Social participation came up in a number of discussions. At every focus group, participants expressed that they would like to be involved in events that were friendly and hoped to meet nice people:

“We could have more events at community centres.”

“[If I was boss] I would create more hobby classes that are accessible and friendly.”

3.5. Respect and Social Inclusion

The participants did not feel welcome and included everywhere in their local community. In many cases, participants spoke of not feeling safe. The participants expressed a desire for a change of attitude in the community toward people with intellectual disabilities:

“I wish people were more friendly to people with intellectual disability, and that things could be slower.”

Interactions in public spaces were discussed, such as experiences with retail staff in shopping centres:

“Sometimes when I go to the shops, people just look at me … if I need help with the money side … so I think the council could train people to help people with disability and just be like … ‘okay, are you sure you’re all right with this? We can help you out, if you need any more help, just call us back’, not just like shove us off like we’re rubbish.”

Some participants suggested what was needed to remedy the problems they faced:

“[Councils] should be doing like going to businesses and training them. Respectfully, if someone comes in with any disability, or just a mild disability even, just to give them a bit of a hand, not just push us away and half the time, people don’t understand about us …”

The role of the place and space in supporting people to feel safe, socially connected and included was a strong theme in the data. As mentioned in the transportation theme, public spaces, such as train stations, were physical places where people often did not feel safe. Conversely, the participants expressed that they really enjoyed visiting their local café and regularly seeing people who they knew. They often had favourite shops and locations where there were familiar faces and people they knew who they could chat with and stay for a while in order to talk and feel happy. For some participants, this was a café; for others, it was the local pool or shopping centre.

“I go to my café for coffee when I can. Then I go to Priceline [chemist]. There are good shops there … and I know people.”

3.6. Civic Participation and Employment

Civic participation and employment addresses opportunities for citizenship, unpaid work and paid work. Particularly relevant to civic participation in the discussions in the focus groups were issues around consultation and being heard. Most participants were unaware of some of the ways that they could have their say. This raised discussions around whether the ways of contributing were accessible. Many participants said they had not been asked about their experiences and preferences in the community before, and they had little knowledge of being informed by or actively included in wider community or council consultations.

“If I was the boss at [my council] I would make sure I listened to people. People don’t listen to me when I have a problem.”

“There are too many things happening in the disability world where people making the decisions don’t have a disability.”

“We should be going to businesses and training the businesses. They should treat us better. Council should know better.”

“I find the council staff helpful and I know what I like to say but I stumble on my words, I appreciate people’s patience and people generally have an understanding.”

As discussions progressed and participants became more aware of a local council’s scope of responsibilities in the community, they expressed that it would be beneficial if the local council, along with other community businesses and organisations, employed people with intellectual disabilities. When they were aware of representative committees or consultative groups, there was concern around position rotation for multiple perspectives.

In every focus group, the importance and value of having a job arose for discussion. There were participants at each focus group that spoke about how much they would like to have a job and talked about what they would like to do:

“I’d like to work in an office or a café.”

“I would like to be a policeman.”

“A job would be good for me.”

“I would like to work but there are not many opportunities.”

A common feeling among participants who had experience with councils was that the councils could be community leaders in employing people with disabilities. These would need to be paid as advisory positions embedded in multiple council representative groups.

“It would be good to have more jobs for people with intellectual disability, we would feel included then.”

“[If I was the boss of the council] I would employ people with disability.”

In all focus groups, there were discussions about the kinds of employment people with intellectual disabilities could have through local councils. At a minimum, the participants wanted the opportunity to contribute to advisory councils, not only regarding disability, and those present agreed that they should be paid for their time. In some focus groups, participants suggested other ways that local councils could employ people with intellectual disabilities:

“We could work at the front desk and be welcoming.”

“I would like to work doing the gardening or at the pool.”

3.7. Communication and Information

In all the focus groups, the relevant DIAPs (Disability Inclusion Action Plans) were printed and were available for discussion. Almost all of the participants were unaware of what a DIAP was and had not seen their local council’s DIAP. Some DIAPs in NSW have been made to be easy to read, but participants were not as engaged in the contents of the DIAP as they were in the focus group discussions.

Accessible communication delivered in multiple modes was something that participants clearly requested in every focus group. People with intellectual disabilities are disadvantaged in the community in providing feedback to local governments if communication methods are not accessible. We heard that participants really want to know what is available, where there are safe and inclusive places to go and how to get around their community.

“The best way to let us know about events in [our local area] is to send us a message on our phones. That would make us feel welcome.”

“If you want us to participate, we need to know what things are happening, and when.”

The importance of easy-read versions of all citizen information packs was reinforced in every focus group.

“Easy-read is a good idea. That is something Council should do [more of].”

“You could have an easy-read app on the phone that told you what was happening.”

“All flyers and info should be in easy-read.”

“It would be a good idea to have touch screen maps in the community—with pictures [as well as words].”

“Get in touch with us by an accessible email, newsletter or website.”

Explaining important safety and emergency information more clearly and in more accessible formats was also discussed:

“We need better notification in case of an emergency.”

“You should have a council helpline.”

“If I was the boss of my council I would text people to let them know they can call council.”

“Email everyone when there are changes.”

Signage and wayfinding emerged as a theme in focus groups, with participants expressing the importance of making signs easier to understand:

“Have easy-read everything.”

“I would have bigger signs.”

“Have touchscreen maps in the community.”

We also found that some information was valued more than other information. For example, some local governments had created an easy-read document out of the Disability Inclusion Action Plans—which are strategic reports required from every local government in Australia. Based on the feedback from participants, this was not considered to be the most useful information for people with intellectual disabilities. Rather, participants asked for a “What’s On” of events and activities, i.e., a local community calendar.

3.8. Community and Health Services

Health services were not specifically discussed in the focus groups as this was seen to be outside of local government practices. Community support was referred to in some focus groups. In one focus group, a participant explained that the only reason he knew about the local library was because his support person took him there. In another focus group, a participant explained that the lack of public toilets caused some problems for him, his friends and their support person, who was responsible for travelling with a number of people with intellectual disabilities on outings. Another participant mentioned attending the local library to learn to read.

4. Discussion

This report expands on current evidence by conceptualising how inclusion is framed for people with intellectual disabilities in a way that is relevant to the responsibilities of local governments, councils and municipalities more broadly, by adapting an inclusive city framework in order to organise responses. The depth and insight demonstrated by the focus group resulted in evidence that people with intellectual disabilities (mild, moderate and severe) have valuable information to share with local governments about their lived experiences of inclusion in the wider community.

As people with intellectual disabilities are less likely to be included in civic governance [

32] or to be asked their opinion about experiences of inclusion and exclusion in the local community, their needs and preferences are also less likely to be understood or implemented. In public policy, advocacy and service delivery, people with intellectual disabilities have become increasingly included in the generic grouping of “people with a disability” [

33]. There is a risk that the inclusion needs of people with intellectual disabilities could be missed as a result of the de-differentiation of disability policy and strategy [

34]. This highlights the importance of developing inclusive and collaborative tools and processes in order to ensure that people with intellectual disabilities can participate in civic and social discourse.

People with intellectual disabilities cannot participate in the community and cannot provide feedback to local government if communication methods and pathways are not accessible. A person with an intellectual disability may take longer to learn things or may have difficulty reading, writing or communicating. In order to make improvements to engagement and inclusion, all communication methods need to be accessible and be at an appropriate literacy level, such as “easy-read” English. Easy-read English has been researched from the perspective of health information for a number of years [

35]; however, less research has been conducted on how to evaluate accessible communication and its direct relationship to levels of social and community participation [

36].

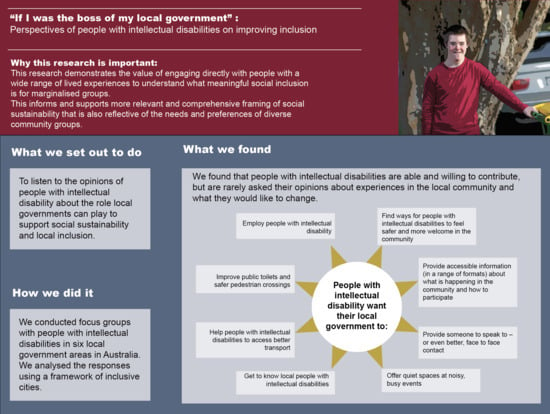

When it comes to communication, the message from people with intellectual disabilities is diversity and flexibility. What this means is providing a range of communication types and pathways in order to accommodate individual preferences (email, telephone, direct person-to-person, texting, etc.). Local governments can consider more flexible ways of providing information and communicating with citizens. For example, considering easy-read English brochures, webpages, texting and well-designed signboards in situ. A synthesis of recommendations emerging from the focus groups illustrate what people with intellectual disabilities want to tell their local governments about inclusion (

Figure 1).

The responses from the focus groups revealed that people with intellectual disabilities have very clear opinions about how their local communities can be made to be more inclusive. The participants were well aware that, as a person with an intellectual disability, they are rarely asked their opinions. The results from the focus groups indicated that the information people valued most included the events happening in their community, where there are safe and inclusive places to go and how to get around their community.

In addition to the physical implications of the built environment, it became clear during the focus groups that the design of our built environments, on urban and public scales, influence the way that people make use of space and places to see people they know, to encounter people if they are feeling lonely, to feel connected to their community and as a way to feel safe.

One of the most commonly discussed topics across all focus groups was the desire for safe places and respectful encounters in the community. These discussions about feeling unsafe or disrespected in public spaces, or about impatient, unkind or unfriendly people, concur with earlier research into the experiences of people with intellectual disabilities [

16] and the ways that space and place influence relationships and the sense of belonging [

37].

Action Opportunities for Local Governments

In light of the findings and in alignment with the inclusive cities approach that incorporates social sustainability, local governments can take action in a number of ways to include people with intellectual disabilities in local community life. The following recommendations are in order of prevalence within the focus groups’ discussions:

Respect, safety and social inclusion: Respect and attitude training for businesses/retail and local government to shift assumptions and provide tools to improve the attitudes of retail and front desk staff in the community.

Civic participation and employment: Support inclusive employment initiatives. Local governments can demonstrate inclusive employment by modelling change and employing people with intellectual disabilities.

Communication and information: Have easy-read English communication as a pre-requisite for all web and print information shared. This does not mean two versions of one document, but rather, a single, well-designed, easy-read English version of all public facing information.

Transportation: Raise awareness of how people with disabilities rely on public transport and what their experiences are while using public transport, including safety and wait times. Advocate for people with intellectual disabilities when negotiating and planning state government transport solutions in local areas.

Outdoor spaces and buildings: Consider public spaces that are designed and activated for social connection and support feeling safe in the community.

Social Participation: Encourage services, activities and community groups that offer opportunities for people with and without a disability to meet, engage in shared activities and build social connections within and throughout the local community. These activities are not necessarily specialised or disability-specific, rather, existing activities can be made more welcoming and be adjusted to ensure that people with intellectual disabilities are aware of and have opportunities to participate in a meaningful way.

Governance and community engagement activities: Paid inclusion on advisory panels. Recruiting appropriately and designing processes and materials that are inclusive of the communication requirements of people with intellectual disabilities.

The findings from this research have many implications for how local governments plan, design and implement services, public spaces and precincts that are sensitive to the inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities. Approaches that take into consideration the experiences and preferences of marginalised groups contribute to the social sustainability of communities and local neighbourhoods by supporting civic and social inclusion. Given our findings about safety and respect in public space, there is an opportunity to further research how the designs of built environments impact community attitudes and behaviours from a social inclusion, respect and well-being perspective.

5. Conclusions

There is established evidence that people with intellectual disabilities participate less in civic and social life than non-disabled and other disability groups [

38], and that inclusion in the community is a complex and dynamic process [

39]. It is by listening and responding to the opinions and preferences of people with intellectual disabilities that inclusive practices can be made relevant and can meaningfully contribute to greater social sustainability of local communities [

40]. The findings from this paper will contribute to the growing number of practices implemented across the globe that create a more inclusive and socially sustainable society.

People with intellectual disabilities who participated in this research highlighted that practices that influence inclusion span not only the physical accessibility of space, but inclusive communications and social inclusion. Asking participants “What would you do if you were the boss of your council?” proved to be an effective way of asking participants to share what local government changes could be made for good when it comes to their experiences of inclusion. It also highlighted the importance of providing a forum where people with intellectual disabilities can share their insights of inclusion and exclusion in the community, as a result of their lived experiences.

More than ever, local governments have an opportunity to put in place measures to support inclusion in ways that are well within their current directives in the Local Government Act, including:

By listening to people with intellectual disabilities and hearing how they want to be a part of the community and want to be communicated with, local governments can ensure that they can better meet their responsibilities. This also encourages practices of inclusion, knowledge sharing and community connectedness in order to drive societies toward a future that is socially sustainable and includes people with intellectual disabilities.

Implications for Further Research

This study shows that people with intellectual disabilities do want to contribute to their local community and can add value and perspectives to the progression of inclusive practices and environments. However, as this is only one study of 45 participants, further research is required in order to establish a baseline that can be compared and contrasted across Australian states and internationally. Further research is warranted that explores in detail how people with intellectual disabilities use and enjoy public spaces and what elements and details support social participation. This knowledge is critical in order to ensure the social sustainability of our diverse communities.