1. Introduction

According to a 2020 World Wildlife Fund (WWF) report [

1], wildlife populations have declined by 68% since 1970 due to their over-consumption by poor local people living in or near national parks. According to Duffy, St John, Büscher and Brockington [

2], poverty is the main reason for illegal wildlife hunting by locals, who then sell the hunted wildlife at high prices as a source of income. CITES, the Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, reports that international wildlife trade is estimated to be worth billions of dollars per year, affecting hundreds of millions of animal and plant specimens [

3,

4]. It is important to alleviate poverty among local people to save wildlife. Increased incomes will reduce the local dependence on wildlife. Ecotourism is defined by the International Ecotourism Society (TIES) as “responsible travel to natural settings that conserves the environment and enhances the well-being of local people” [

5]. TIES is an example of a non-profit organisation devoted to aiding businesses by implementing ecotourism practices and fostering long-term community development. Poverty is the main cause of illegal wildlife hunting among local communities, causing widespread wildlife extinction, so ecotourist groups have introduced local ecotourism plans [

6,

7] to develop the local economy to eliminate the local over-dependence on wildlife. Through local ecotourism, communities have been given opportunities to run homestay businesses to obtain economic benefits from the resulting profits [

8]. Many homestays have been established by locals in or near national parks to provide accommodation facilities and experiences to ecotourists [

9]. However, it was found that tourists prefer [

8] to stay in hotels or resorts located in cities [

10,

11] rather than choosing local homestays as their holiday accommodation [

12,

13,

14,

15]. As a result, local homestay businesses are unprofitable and this sector is stagnant [

16,

17]. Staying in a local homestay for wildlife conservation is deemed as responsible behaviour in this study. Ecotourists are those who travel in a natural area and spend a predetermined number of days developing the local economy [

18,

19]. They are responsible people who care about maintaining and protecting the natural environment [

20,

21]. Ecotourists display responsible economic behaviour as they are willing to do everything that others expect them to do, even when confronted with challenging situations [

22]. They will stay in a local homestay for the purposes of wildlife conservation. However, to what extent do they intend to stay in local homestays for wildlife conservation during their visits to a national park? To answer this question, it is vital to understand ecotourists’ responsible economic behaviour in relation to wildlife conservation so an effective marketing strategy for staying in local homestays can be implemented. As tourists and wildlife have a strong emotional connection, the present research study focuses on the relationship between anticipated emotion, attitude and intention.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

Ecotourism is an economic tool for wildlife conservation [

23,

24]. Previous studies involving wildlife conservation through ecotourism highlighted conservation learning that focused on captive wildlife, such as in zoos or aquariums [

25,

26,

27,

28], and conservation interpretation [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. According to Myers [

35], tourists are agents in wildlife conservation. They are responsible people who care about maintaining and protecting wildlife [

20,

21]. Responsible behaviour is the act of doing what should be done in any given situation, even if it is difficult, unpleasant or unclear [

36]. There are three main types of responsible behaviour, namely environmentally responsible behaviour, socially responsible behaviour and economically responsible behaviour [

37]. However, scholars of tourist responsible behavioural research tend to study environmentally responsible behaviour [

38,

39,

40] and socially responsible behaviour [

41,

42]. For example, Xu, Kim, Liang and Ryu [

43] conducted a case study of Nansha Wetland Park in China to examine the links between tourist involvement, experience and environmentally responsible behaviour. He, Hu, Swanson, Su and Chen [

44] conducted a study of tourists’ environmentally responsible tourism behaviour and perceptions of destinations and quality. Su and Swanson [

41] analysed the effect of destination social responsibility on tourist behaviour. Luo, Tang, Jiang and Su [

42] investigated socially responsible tourists’ awareness of environmentally responsible behaviour. In tourism economics research, studies have proven that tourists are willing to pay for wildlife conservation [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]; however, no studies have been undertaken on tourists’ economically responsible behaviour. In the present research, ecotourists staying in local homestays for wildlife conservation is referred to as responsible economic behaviour.

The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) was developed by Ajzen in 1991 for studying the human decision-making process [

53] and it is widely used in conservation behavioural research [

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59]. It consists of three important components, namely attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioural control, which are used as important determinants in understanding human behaviours [

53]. In psychological terms, attitude refers to a person’s mental and emotional state [

60]. It can enable a better understanding of how humans perceive the world and how they behave [

61]. It involves an overall evaluation of attitude objects, e.g., favour or disfavour, or like or dislike [

62,

63]. In wildlife value orientation [

64], a beneficial interaction between humans and wildlife exists when humans have a positive attitude towards wildlife conservation [

65,

66]. Previous studies indicate that local communities [

67,

68,

69,

70], stakeholders [

71,

72,

73,

74,

75] and teachers [

76] have positive attitudes towards wildlife conservation. However, ecotourist attitudes towards wildlife conservation remain unclear. According to Newhouse [

77], ecotourist attitudes have major implications for wildlife conservation. Based on Ajzen [

53] in the TPB, attitudes are antecedents of intention. Intention is the individual willingness to undertake a particular behaviour, so it has a direct relationship with behaviour [

53]. The TPB explains that the more an attitude relates to a behaviour, the greater the intention to perform the behaviour [

53]. In tourism research, several studies have confirmed that ecotourist attitudes have a direct effect on intention, as shown by research conducted by Clark Mulgrew, Kannis–Dymand, Schaffer and Hoberg [

78]; Phu, Hai, Yen and Son [

79]; Meng and Choi [

80]; and Gstaettner, Rodger and Lee [

81]. Based on the arguments above, the present study proposed the first research hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Attitude to staying in a local homestay for wildlife conservation has a significant direct effect on intention to stay at a local homestay for wildlife conservation.

The importance of emotions in the decision-making process is often overlooked by scholars because they believe rational thinking is more meaningful. They regard emotions as irrational phenomena that can lead to incorrect thinking. However, current ideas emphasise the significance of emotions in decision making. Loewenstein and Lerner [

82] distinguish between two sorts of emotions encountered during decision-making: anticipated emotions and immediate emotions. Emotions that are anticipated (or predicted) are not experienced immediately, but are anticipated as a result of the rewards or losses arising from a decision. The two effects that exist in anticipated emotion are self-consistency (e.g., pride and guilt) and basic hedonic (e.g., pleasure and frustration). Self-consistency shows a long-term emotional effect while basic hedonic is more short-term [

83]. Bagozzi, Belanche, Casaló and Flavián [

84] mentioned that anticipated emotion plays an important role in purchasing decision making. Emotion is widely used by major companies and organisations in marketing strategies to influence buyers’ emotions by placing emotional taglines in their marketing adverts. Some examples are the ‘Choose Happiness’ tagline, used in Coca Cola ads; the ‘Stop Climate Changes Before It Changes You’ tagline by the World Wildlife Fund, which adds the element of fear; the ‘30+ Years’ Experience Successfully Representing Accident Victims’ tagline by John Rapillo, a law office that uses the element of trust; the ‘Help Me Read This’ tagline by Children Of The World, which features a sad element; or ‘You’re Not You When You’re Hungry’ for the Snickers bar (Mars), which uses an element of humour by displaying an awesome picture of Godzilla, except when he is hungry. Surprisingly, adverts that include emotional elements are generally successful in influencing users/customers to buy products or services. In tourism research, studies also show that tourists have a strong emotional connection with wildlife through their wildlife view experience [

85,

86,

87]. This research assesses how tourists’ anticipated emotions in relation to wildlife affect their decisions to stay in local homestays for wildlife conservation. In the TPB, scholars tend to relate environmental research to norms [

88,

89,

90,

91,

92]. However, in their study, Onwezen, Antonides and Bartels [

93] suggest that exploring anticipated emotion in environmental research is critical. Moreover, a meta-analysis conducted by Rivis, Sheeran, and Armitage [

94] mentioned that anticipated emotion can increase the variance in explaining attitude and intention in the TPB. In TPB research, previous studies by Kim, Njite and Hancer [

95] and Londono, Davies and Elms [

96] have shown that anticipated emotion has a significant direct effect on attitudes to behaviour and intention. Based on the arguments above, the present study proposed further research hypotheses as follows:

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Anticipated emotion has a significant direct effect on attitude to staying in a local homestay for wildlife conservation.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Anticipated emotion has a significant direct effect on intention to stay in a local homestay for wildlife conservation.

Mediation analyses are often used in social psychology [

97] to investigate the underlying mechanism or process by which one variable influences another via a mediator variable in order to better understand a known relationship. When no evident direct relationship exists between an independent variable and a dependent variable, mediation analysis might enable a better understanding of the relationship [

98]. In tourism behavioural research, attitude has been identified as functioning in a mediator role [

99]. Studies by Rahman, Rana, Hoque and Rahman [

100] showed that tourists’ attitude has the effect of mediating between service and satisfaction. Mehmood, Liang and Gu [

101] determined that attitudes mediate the relationship between user-generated content and travel intentions. Studies conducted by Gilchrist, Masser, Horsley and Ditto [

102]; and Taylor, Ishida and Donovan [

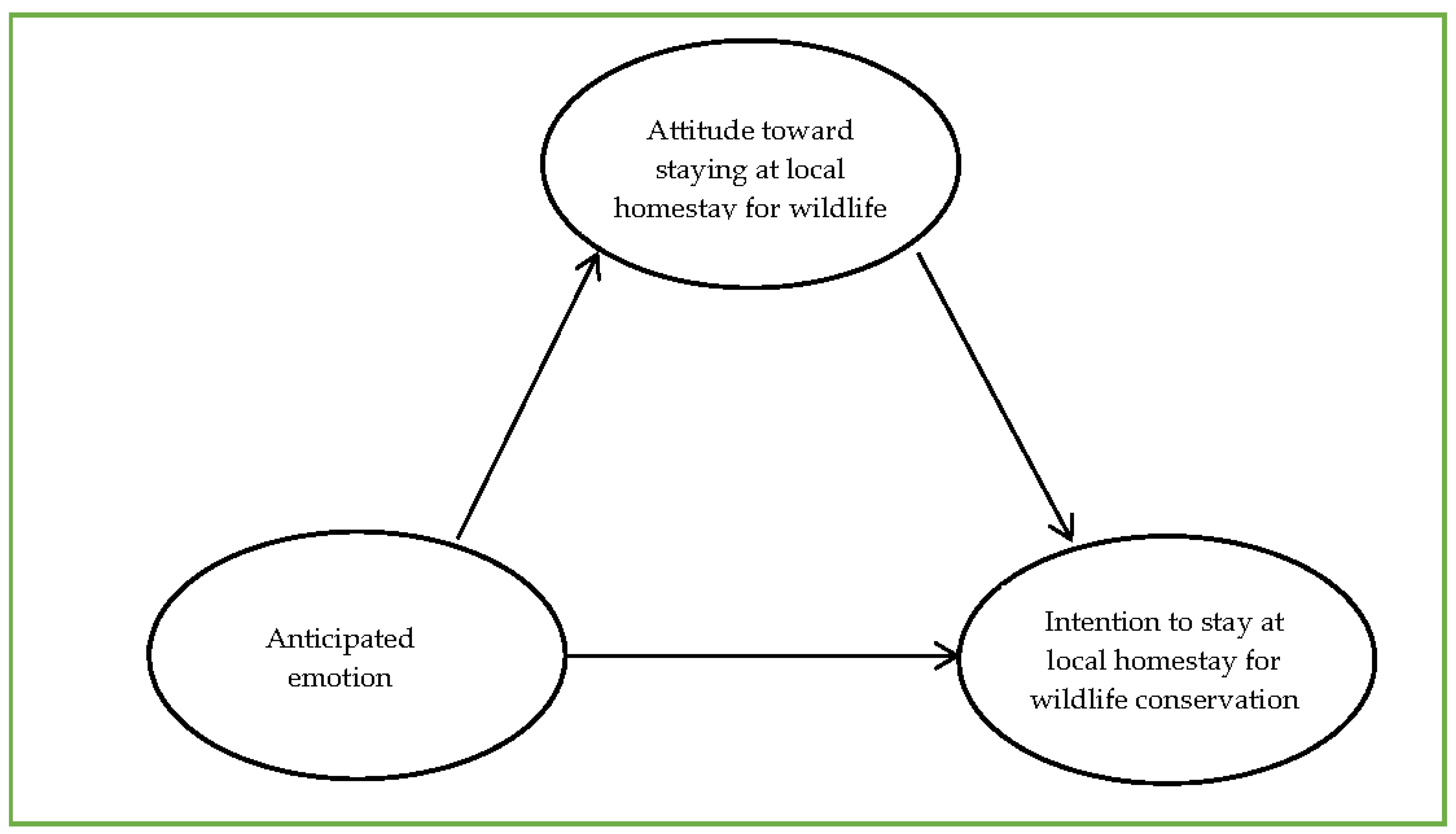

103], indicate that attitude mediates the relationship between anticipated emotion and intention. The proposed research framework, illustrating the relationship between attitude, anticipated emotion and intention, is shown in

Figure 1. Based on the arguments above, the present study proposed a further research hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Attitude to staying at a local homestay for wildlife conservation mediates the relationship between anticipated emotion and intention to stay at a local homestay for wildlife conservation.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This research examined the mediator roles of attitude towards staying in a local homestay for wildlife conservation between the relationship of anticipated emotion and intention to understand ecotourist responsible economic behaviour. The study revealed that attitude towards staying in a local homestay for wildlife conservation has a significant direct effect on intention to stay in local homestays for wildlife conservation. This result is in line with studies conducted by Clark Mulgrew, Kannis–Dymand, Schaffer and Hoberg [

78]; Phu, Hai, Yen and Son [

79]; Meng and Choi [

80]; and Gstaettner, Rodger and Lee [

81]. The study also proves that anticipated emotion can influence attitude since the results indicate that anticipated emotion has a significant direct effect on attitude towards staying in a local homestay for wildlife conservation. These results support those of previous studies by Kim, Njite and Hancer [

95] and Londono, Davies and Elms [

96]. The study also shows that anticipated emotion can highly influence intention since the results indicate that anticipated emotion has a significant direct effect on intention to stay in a local homestay for wildlife conservation, which is in line with previous studies [

95,

96]. The study also confirmed that attitude is a mediator between anticipated emotion and intention, since the study revealed the mediating effect of attitude to staying in a local homestay for wildlife conservation between anticipated emotion and intention to stay in a local homestay for wildlife conservation. This result is also supported by the findings of previous studies by Gilchrist, Masser, Horsley and Ditto [

102] and Taylor, Ishida, and Donovan [

103]. The high variance in explaining attitude and intention shows that anticipated emotion plays an important role in understanding economically responsible ecotourists’ attitudes and intentions to stay in local homestays for wildlife conservation. In practical terms, the current study has proven that a responsible ecotourist’s attitudes and intentions are influenced by his/her anticipated emotions. Therefore, it is suggested that an emotional element is considered in advertising that promotes a local homestay. This would resemble the actions of major companies and organisations, e.g., Mars, Coca Cola, and the World Wildlife Fund, which have promoted their products and services in this way. For example, players in the ecotourism industry can use narratives and storytelling strategies to market a local homestay by creating an emotional connection between tourists and wildlife. Since colours have a scientifically proven association with human emotions, stakeholders could also practise this technique in their marketing strategies. Although the influences of colours vary according to gender, stakeholders could consider the power of colour itself to influence others. For example, black and purple are related to being strong, powerful and masterful; red is arousing; blue is soft. The colour Facebook uses is blue and that of Coca-Cola is red; this is no coincidence. Word-of-mouth techniques (through testimonials, customer reviews, logos, or real customer stories) are also important in instilling trust in a tourist. Trust will eventually produce a positive emotional reaction, such as ‘If other people trust them, I should too’. Airbnb is well-known for using the simple yet strong word-of-mouth method. Since this study has determined that attitude mediates the relationship between anticipated emotion and intention, it is also suggested that players in the ecotourism industry conduct strategic planning on how to improve the attitudes of responsible ecotourists to wildlife conservation. The more positive the attitude to wildlife conservation is, the higher the chance that a responsible ecotourist will stay in a local homestay to help the local economy. An effective marketing strategy would induce responsible ecotourists to choose a local homestay rather than other accommodation.

To summarize, ecotourists are particularly responsible for wildlife conservation when they are willing to stay in local homestays and pay for their accommodations to aid the local economy through changes in their attitudes and emotions. This study has some limitations due to time constraints. Although this study found that attitude and anticipated emotion greatly influence behavioural intentions, the study did not consider the effect of behavioural intentions on the actual behaviour of responsible ecotourists. According to Ajzen [

53], not all intentions have a significant effect on actual behaviour. It is recommended that future researchers conduct a study of economically responsible ecotourist behaviour using the Theory of Planned Behaviour.