Abstract

Youth environmental activism is on the rise. Children and youth with disabilities are disproportionally impacted by environmental problems and environmental activism. They also face barriers towards participating in activism, many of which might also apply to their participation in environmental activism. Using a scoping review approach, we investigated the engagement with children and youth with disabilities by (a) academic literature covering youth environmental activism and their groups and (b) youth environmental activism group (Fridays For Future) tweets. We downloaded 5536 abstracts from the 70 databases of EBSCO-HOST and Scopus and 340 Fridays For Future tweets and analyzed the data using directed qualitative content analysis. Of the 5536 abstracts, none covered children and youth with disabilities as environmental activists, the impact of environmental activism or environmental problems such as climate change on children and youth with disabilities. Fourteen indicated that environmental factors ‘caused’ the ‘impairments’ in children and youth with disabilities. One suggested that nature could be beneficial to children and youth with disabilities. The tweets did not mention children and youth with disabilities. Our findings suggest the need for more engagement with children and youth with disabilities in relation to youth environmental activism and environmental challenges.

1. Introduction

Children and youth environmental activism movements have been on the rise in recent times [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Children and youth with disabilities are impacted by environmental issues, such as natural disasters, and by their discussions [7,8,9], the very focus of and changes pushed by environmental activism [10,11] and by the perceptions people involved in environmental activism have of children and youth with disabilities [12]. Many roles for youth in relation to environmental issues and activism are present in the academic literature, such as their role of being researchers [13,14,15,16,17], educators [18,19,20,21,22,23,24], and environmentally considerate consumers [25,26]. Children and youth with disabilities could fill the same roles and also bring specific knowledge linked to their lived experiences in general and especially concerning the ability-based expectations, judgments, norms, and conflicts they constantly experience in relation to persons without disabilities [27] to environmental activism in all roles. These contributions would be useful as environmental activism generates ability-based expectations, judgments, norms, and conflicts between humans [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36].

Given the potential impact of environmental activism and environmental problems on children and youth with disabilities and the specific knowledge children and youth with disabilities could bring to children and youth environmental activism, we used a scoping review approach to answer the following research questions: (1) How and to what extent are children and youth with disabilities engaged with as acting activists within youth environmental activism in the academic literature focusing on children and youth environmental activism? (2) How and to what extent does the academic literature that focuses on children and youth environmental activism engage with the impact of children and youth environmental activism on children and youth with disabilities? (3) How and to what extent does academic literature that focuses on children and youth environmental activism link environmental problems to children and youth with disabilities? (4) How and to what extent does the academic literature that focuses on children and youth environmental activism cover children and youth with disabilities in relation to the positive effect of the environment? (5) How and to what extent are children and youth with disabilities covered by Fridays For Future tweets? We used empowerment theory, existing literature discussing children and youth environmental activism, and the cultural reality of ability-based expectations, judgments, norms, and conflicts to discuss our findings.

1.1. Youth Environmental Activism

Environmental activism has a long history [37,38,39,40,41], can be demonstrated in various ways [42], such as pro-environmental behavior, protests, social media activism, environmentally considerate consumerism, petitions, and political participation [4,43] and covers many topics [43,44,45,46]. Many academic articles cover youth in relation to environmental activism [23,26,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56] including environment-related views held by youth [57,58] and many make the point that youth were excluded from debates around environmental issues [59,60,61].

Youth activism is in general a place for learning [62], influencing, and shaping one’s identity [62], such as the civic actor identity. It can empower youth to understand their role in society and have agency in their own lives [62] and it enables youth to develop a positive self-identity and a sense that they are capable and can make a difference [62]. Being an activist can improve one’s psychological well-being [63], as “youths’ roles as activists for social change intertwine with their need for care, healing, and personal replenishment, thereby sustaining their agency” [52] (p. 11). Youth also make environmental activism part of their social activist identity [23,57,64].

Many articles state that youth are impacted by environmental issues [15,65,66,67,68]. Many competencies needed by youth as environmental activists [69,70,71,72] and roles for youth within environmental issues and activism are present in the academic literature, such as their role of being researchers [13,14,15,16,17], educators [18,19,20,21,22,23,24], and environmentally considerate consumers [25,26]. Various factors influence youth to become environmental activists [65,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83], such as education [84], risk perception [26], and the negative impact of environmental degradation on their lives [85,86]. Youth can also be enticed in various ways to partake in environmental activism [1,2,3,4,5,6,87,88].

Recent youth environmental activism examples are Fridays for Future and Youth4Climate [2,4]. Fridays For Future, a youth movement demanding action on the climate crisis where students skip school to protest outside their local government buildings, has amassed 14 million participants in 214 countries since its start in Sweden in August of 2018 [4,5], while a similar initiative, Youth4Climate, a movement that encourages its protesters to post on social media with the hashtag #Youth4Climate, has 16,300 posts on Instagram as of 28 December 2020 [3]. Various theories are employed to engage with youth as environmental activists, such as youth engagement theory [89], Hart theory of children’s participation [74], youth civic engagement [90], social cognitive theory [21], ecopsychology [23], civic developmental theory [72], ecosocial work [52], and environmental citizenship [91].

1.2. Children and Youth with Disabilities as Activists

Persons with disabilities have had a long history as activists within society [92,93], including their participation in activism that aimed to improve the situation of persons with disabilities, including children and youth with disabilities, in society [93,94]. It is recognized that involving persons with disabilities in public activism is important [95] and that persons with disabilities, including children and youth with disabilities, are the experts of their current social situation [96], and as such, can and should be involved in generating missing evidence [97,98,99,100]. Children and youth with disabilities also take on a role as advocates within the world [101]. However, persons with disabilities, including children and youth with disabilities, are often invisible in environment-related discourses [8,9,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109], and encounter numerous barriers to being a part of traditional forms of activism, such as marches, in-person protests, volunteering for organizations, or attending government meetings [95,110]. Being a part of activism such as the 2017 online disability pride march led participants to feel “a stronger sense of responsibility to raise awareness of disability rights, promote policy change, and be more vocal and active in future activism” [95]. Unfortunately, many of these actions are viewed as “‘slacktivism’—low-effort and low-impact alternatives to meaningful engagement with a cause” [95] (p. 1), as “activist rhetoric often refers to ‘putting your body on the line’ or ‘being in the streets’” [95] (p. 1).

1.3. Environmental Issues, Environmental Activism, and Persons with Disabilities Including Children and Youth with Disabilities

The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) [111] and The United Nations 2018 Flagship Report on Disability and Development: Realization of the Sustainable Development Goals by, for and with Persons with Disabilities [7] are just two examples of documents outlining the many social issues that persons with disabilities, including children and youth with disabilities, face that require activism including environmental activism by persons with disabilities, including children and youth with disabilities. Many academic studies outline the problems persons with disabilities face in relation to natural disasters, disaster preparedness [8,9,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109], and environment-related topics [112,113]. However, persons with disabilities, including children and youth with disabilities, are not only impacted by environmental issues, but also by how environmental activism is performed. Persons with disabilities, including children and youth with disabilities, could be impacted by:

- (a)

- potential arguments (preventing impairment) for environmental actions;

- (b)

- changing societal parameters caused by environmental activism;

- (c)

- changing societal parameters demanded by environmental activism, and;

- (d)

- technologies used as a solution for environmental issues (e.g., geoengineering and human enhancement to make humans resistant to climate change).

The question is, which of these potential impacts are evident in and engaged with in the youth environmental activism literature in relation to children and youth with disabilities?

Persons with disabilities, including children and youth with disabilities, face many barriers in relation to being part of environmental discourses. For example, persons with disabilities reported in online fora covering the 2030 sustainable development goals that they did not feel a part of decision-making processes in relation to sustainable development issues, in part because of the dominance of the medical imagery applied to them, which prevents people from realizing that persons with disabilities have a stake in many social issues discussed [92,114,115,116,117].

Various studies indicate the importance of identity in relation to getting involved in environmental activism [23,57,64] and the concepts linked to identity such as environmental citizenship [91]. As to persons with disabilities and children and youth with disabilities, identity can play itself out in one of two ways. One is how one defines themselves and is defined by others, and the other is what identity do persons with disabilities including children and youth with disabilities see themselves as having in relation to the role they play in environmental discourses.

As to the imagery of persons with disabilities, including children and youth with disabilities and their problem, one has two options: one can see persons with disabilities, including children and youth with disabilities in a negative/medical imagery with ‘their disability’ in need of prevention or fixing, or one can see persons with disabilities including children and youth with disabilities as ‘normal’, as ability diverse, facing social problems caused by environmental realities or health problems like everyone else. The negative imagery of persons with disabilities to discuss negative environmental issues such as pollution is prevalent in the environmental literature [118,119,120] and often only refers to disabled individuals in medical frameworks [121]. Such one-sided focus is questioned by some [12,30,121,122,123,124] because it ignores that persons with disabilities are impacted socially by environmental issues in a disproportionally high manner, whereby their voice is often not heard in the preparation against environmental disasters or surrounding the remedies after an environmental disaster [8,125,126,127,128]. One article, for example, narrows in on children with disabilities and the social vulnerabilities they may face in disasters and their aftermath [129].

1.3.1. Potential Conceptual Contributions by Children and Youth with Disabilities to Environmental Activism

Children and youth with disabilities have an essential contribution to make to environmental activism, namely their daily experience of ability-based expectations, judgments, norms, and conflicts. Many children and youth with disabilities are sensitized through their lived experience to ability-based expectations, judgments, norms, and conflicts between groups. As such, they are perfect to bring the ability-based sensibility and lens to environmental activism. Environmental activism influences the ability expectations humans have of nature and of each other. Environmental activism denounces ability expectations some have and generates new ability expectations. As such, environmental activism can be expected to lead to ability expectation conflicts between groups and individuals, and ability-related literacy is needed to understand the unique ability needs of different groups and the potential conflicts. Ableism was coined by the disability rights movement to give a name to the societal reality of ability-based expectations, judgments, norms, and conflicts, and disablism was coined for the often-negative disabling use of such expectations, judgments and norms against persons with disabilities, including children and youth with disabilities [27,122,130,131]. Since its initial coinage, ableism and disablism have been applied not only to persons with disabilities, but also to the relationships between humans in general, humans–animals, and humans–nature [30,36,122,132,133,134,135], humans–post/transhumans, humans–cyborg humans, humans–sentient machines, animal–sentient machines, and nature–sentient machines [110]. Ableism has also been linked to enabling actions such as the capability approach [136,137,138] and the concept of “sustainable development” has been coined to enable nature by changing ability expectations humans have of nature [139]. As to humans–nature relationships, eco-ableism was coined in 2012 by Wolbring “as a conceptual framework to analyze enabling and disabling human ability desires for the environment” [29,132,133]. The framework of anthropocentrism reflects different abilities humans can expect from nature other than eco/bio-centrism [102]. Specific environmental topics such as sustainability, sustainable development goals, Rio+20, the concept of sustainable development, energy security and insecurity, and water footprint have been investigated through an ability expectation and ableism lens [11,12,102,123,124,138,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149].

In one piece focusing on ability expectations humans have of nature, it is stated:

In other words, ecological feminism is rejecting the ability expectation of ‘dominance, competition, materialism, and technoscientific exploitation inherent in modernist, competition-based social systems’ (Besthorn and McMillen, 2002, p. 226) and nourishing the ability expectation of ‘caring and compassion and the creation and nurturing of life’ (Besthorn and McMillen, 2002, p. 226)” [30] (p. 102).

Eco-ability [31,32,33,34,35,150] was coined by Nocella in 2012, stating “[eco-ability] combines the concepts of interdependency, inclusion, and respect for difference within a community; and this includes all life, sentient and non-sentient” [35] (p. 141). Nocella stated further that eco-ability “is a philosophy that respects differences in abilities while promoting values appropriate to the stewardship of ecosystems” [35] (p. 141). Nocella highlighted commonalities between disability studies and eco-ability such as cherishing ability differences, ability uniqueness, and interdependency [35]. Nocella called out many disabling uses of ability normativity in relation to persons with disabilities by environmental and animal rights advocates, such as using the terms freak and schizophrenia [35]. Eco-crip theory is emerging at the intersection of disability studies and the environmental humanities [147].

1.4. Empowerment of Children and Youth Including Children and Youth with Disabilities

Empowerment is an important aspect of the equalization of opportunities for persons with disabilities, including children and youth with disabilities. Empowerment of persons with disabilities is a key indicator in the Community Based Rehabilitation Matrix [151] and is central to justice for persons with disabilities [152], disability rights and independent living (IL) movements [121]. Empowerment is seen as important for one’s independence and self-determination [153], individual and collective health, well-being, and environments [154]. However, for persons with disabilities, many barriers to such empowerment are noted [155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164].

Various attributes [165], factors [165], parameters [154], and indicators of empowerment exist [63,166,167,168], including indicators for youth empowerment, such as the Sociopolitical Control Scale for Youth (SPCS-Y) [169], and tools to measure empowerment in persons with disability [153]. One can make a case that children and youth with disabilities pose specific challenges to fulfill all these attributes, factors, parameters, and indicators. Empowerment is associated with the demand to question oppression, as “structural oppression impacts individuals and hampers their ability to control their lives, which in turn influences their ability to participate fully in economic, social and political processes” [170]. Using empowerment language, the question is, which identities and which roles of children and youth with disabilities are evident and empowered in the environmental activism literature?

Empowerment theory is also employed in relation to environmental activism [171]. In youth empowerment theory, conditions are named that supposedly empower youth to create sociopolitical change [154]. According to empowerment theory, individuals take an active role in the change process, which includes youth [169,172,173]. Empowerment theory allows one to engage with legal, political, economic, social, and other forms of empowerment, understand and deal with inequality, and promote literacy of topics such as intersectionality, identity, agency, and autonomy [170]. Empowerment theory has four categories: psychological empowerment, organizational empowerment, community empowerment, and relational empowerment [174]. Empowerment theory, research, and intervention also link individual well-being with the larger social and political environment [175]. All these aspects of the theory are of relevance to persons with disabilities. A central tenant of empowerment theory is that empowerment can be a process or outcome [63,175,176,177,178,179]. It can be argued that children and youth with disabilities pose a challenge to the process part and the outcome part.

It is recognized that empowerment processes and outcomes are depending on the context they are used in and at the people targeted [63,180,181] and shift over time [177]. Children and youth with disabilities live within a very specific context and, as such, one must engage and understand their empowerment experiences.

Concluding, environmental activism, including youth activism, is on the rise and seen as important, and persons with disabilities, including children and youth with disabilities, are impacted in various ways by environmental issues and environmental activism. Persons with disabilities, including children and youth with disabilities, can also have various roles and identities in environmental activism discourses. The aim of our scoping review was to investigate how and to what extent the academic literature focusing on youth environmental activism and the tweets of the youth environmental activism group Fridays For Future engage with children and youth with disabilities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

Scoping studies are useful in identifying the extent of research that has been conducted on a given topic [182,183] and the current understanding of a given topic. Our scoping study focuses on the extent and how academic literature on youth environmental activism and youth environmental activism groups and the tweets of the youth environmental activism group Fridays For Future engages with children and youth with disabilities. Our study employed a modified version of the stages for a scoping review outlined by [184], namely: identifying the research questions of the review, identifying applicable databases to search, generating inclusion/exclusion criteria, recording the descriptive quantitative results, selecting literature based on descriptive quantitative results for content-coding of qualitative data, and reporting findings of qualitative analysis. The research questions were (1) How and to what extent are children and youth with disabilities engaged with as acting activists within youth environmental activism in the academic literature focusing on children and youth environmental activism? (2) How and to what extent does the academic literature that focuses on children and youth environmental activism engage with the impact of children and youth environmental activism on children and youth with disabilities? (3) How and to what extent does academic literature that focuses on children and youth environmental activism links environmental problems to children and youth with disabilities? (4) How and to what extent does the academic literature that focuses on children and youth environmental activism cover children and youth with disabilities in relation to the positive effect of the environment? (5) How and to what extent are children and youth with disabilities covered by Fridays For Future tweets.

2.2. Data Sources and Data Collection

To maintain a clear and feasible scope [185], we searched on 23 April 2020, the academic databases EBSCO-HOST (an umbrella database that includes over 70 other databases itself including Anthropology Plus, Environment Complete, GeoRef, GreenFILE, covering human impact on the environment, and Environment Complete and Education Research Complete) and Scopus (which incorporates the full Medline database collection) with no time restrictions. These two databases contain journals that cover a wide range of topics from areas of relevance to answer the research questions.

We searched for scholarly peer-reviewed journals in EBSCO-HOST, and we searched for reviews, peer-reviewed articles, conference papers, and editorials in Scopus.

We performed the following search strategies, whereby “*” is a wildcard allowing for various characters in the place of “*” (Table 1).

Table 1.

Search strategies used.

2.3. Data Analysis

To answer the research questions, we first obtained hit counts for our search term combinations (Table 1) employing a descriptive quantitative analysis approach [186,187]. We then exported the Scopus and EBSCO-HOST citations results (with the abstracts) into the endnote reference software for each search strategy and eliminated duplicates between the databases by deleting the duplicates in the Endnote databases generated for each search strategy. The final non-duplicate abstracts for each search strategy were exported from the Endnote reference software as a Word RTF file. The RTF files containing the abstracts for each of the strategies 1a, b, 2a, b, c, d, e, and 3a and the full text from strategy 3a, and the tweets from search strategy 3b were then uploaded into the qualitative analysis software ATLAS.Ti 8™ for directed qualitative content analysis [186,187,188,189] of the data focusing on the research questions. We used directed content analysis to add knowledge about the phenomenon of environmental youth activism and children and youth with disabilities, that “would benefit from further description” [186]. As to the coding procedure, we familiarized ourselves with the content of all articles, abstracts and tweets and identified relevant data [189]. We then independently identified and clustered content into potential subthemes based on meaning and repetition under each of the five top themes which reflect the five research questions [186,190].

2.4. Trustworthiness Measure

Trustworthiness measures include confirmability, credibility, dependability, and transferability [191,192,193,194]. To enhance credibility, both authors coded the files in ATLAS.Ti 8™. Differences in codes and theme suggestions of the qualitative data were few, discussed between the authors (peer debriefing), and revised as needed. Confirmability is evident in the audit trail made possible by using the Memo and coding functions within ATLAS.Ti 8™ software. As to dependability, we provided the exact parameters for the search strategies and provided an extensive introduction section to ground the analysis of our study. It is not the intent of our study to be generalizable, however, the data we provide allows for transferability whereby others can decide whether they might want to perform a similar study [194]. The description of our method gives all the required information for others to decide whether they want to apply our keyword searches on other data sources such as grey literature, or other academic literature, other languages, or whether they want to perform more in-depth searches.

2.5. Limitations

The search was limited to certain academic databases (70 databases accessible through EBSCO-HOST and SCOPUS which includes Medline database journals) and not all academic databases in existence. The search was also limited to English language academic literature. We also only used Fridays For Future tweets from a short time frame. As such, the findings are not to be generalized to the whole of academic literature, non-academic literature, non-English literature, or all Fridays For Future tweets. These findings, however, allow conclusions to be made within the parameters of the searches.

3. Results

3.1. Results Covering Children and Youth with Disabilities in Relation to Environmental Activism and Environmental Engagement

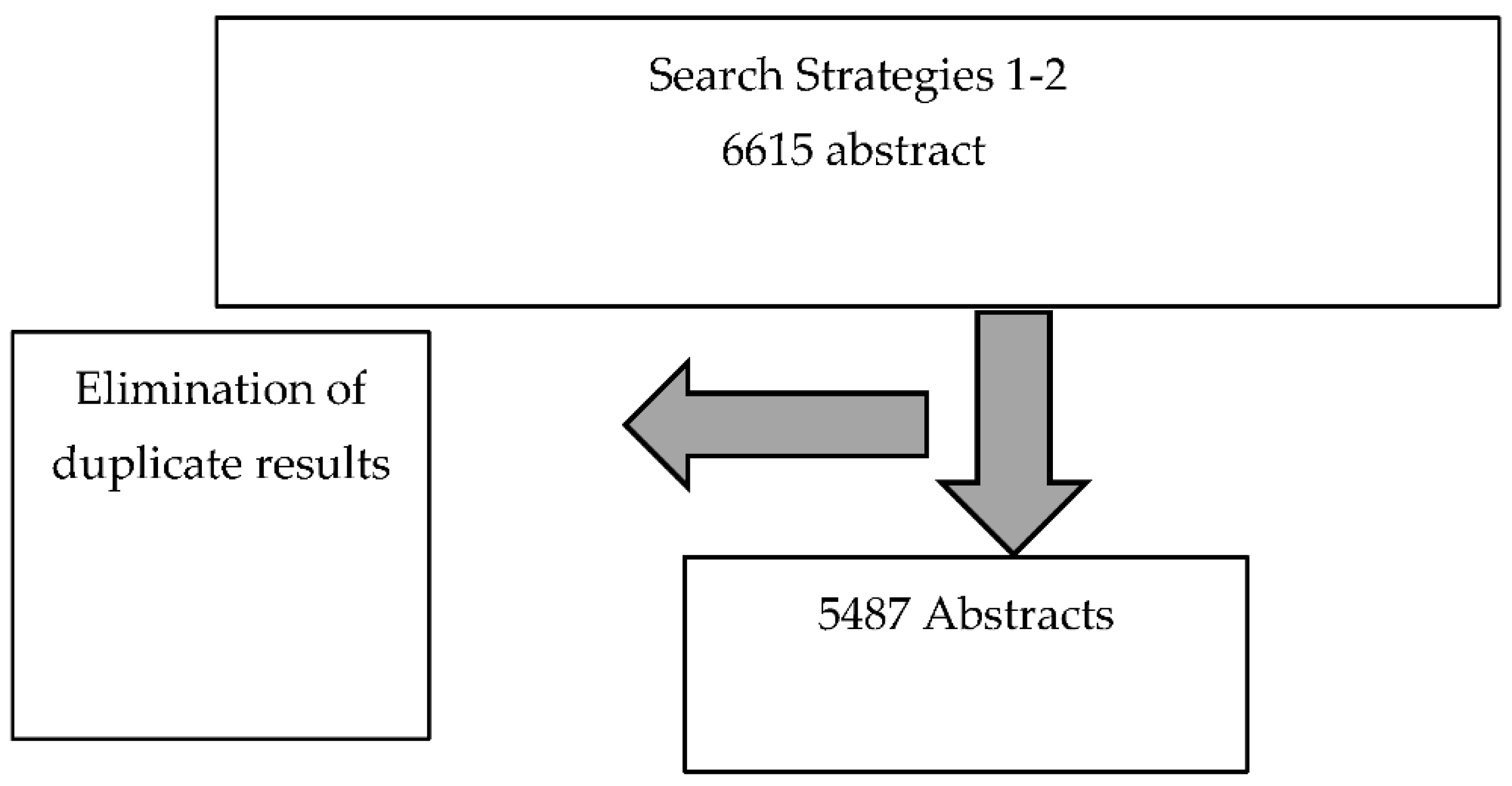

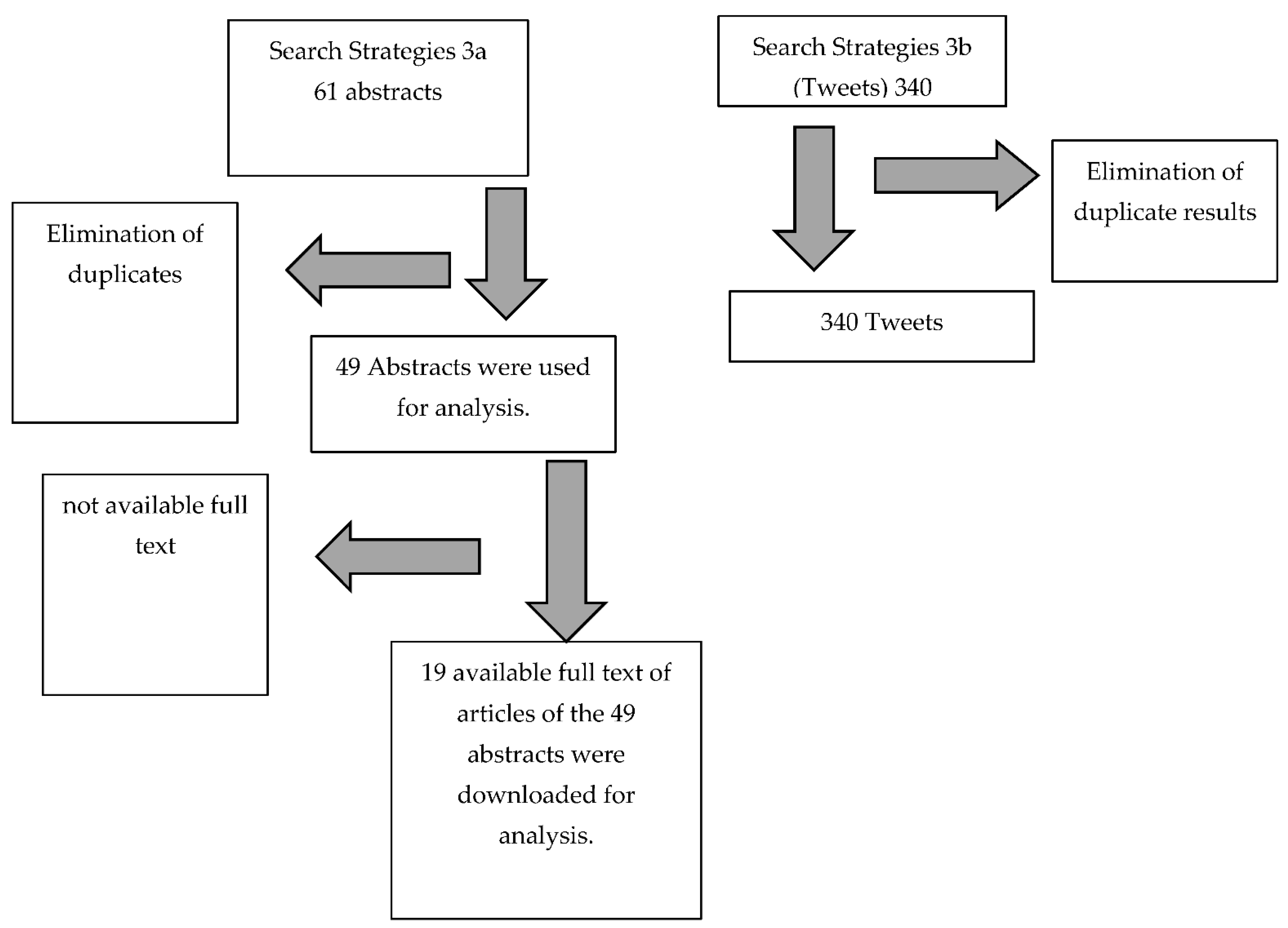

In total, 5487 abstracts were downloaded based on strategies 1 and 2 (Figure 1). Adding the 49 abstracts from strategy 3a (Figure 2), 5536 abstracts were downloaded. We also downloaded the 19 available full text of the 49 abstracts obtained through strategy 3a (Figure 2) and 340 tweets obtained through strategy 3b (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the selection of academic abstracts for qualitative analysis.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of the selection of academic abstracts and full texts covering specifically youth environmental activism groups (strategy 3a) and Twitter tweets from Fridays For Future (strategy 3b) for qualitative analysis.

For the 5487 abstracts obtained through strategies 1 and 2, we deemed to contain relevant content related to research questions R1-R4 we also downloaded the full text of the articles and report on them in Section 3.1.1 and Section 3.1.2, with the exception that we did not seek any full text from the 14 abstracts from subtheme 1 of R3 that focused on environmental issues causing or worsening ‘impairments’ for children and youth with disabilities.

Within the relevant data, we only found subthemes for the top theme reflecting research question R3 and we report this in Table 2 as subthemes and report on these subthemes in Section 3.1.1 and Section 3.1.2. For R1, R2 and R4 we found no subthemes but just the top theme reflecting the research question.

Table 2.

Frequency of relevant abstracts and tweets obtained through different search strategies for each of the five top themes reflecting the five research questions.

In the literature downloaded, content was sometimes found covering persons with disabilities in a way that suggested it could also include children and youth with disabilities without mentioning them. As such, we highlight this in Table 2 as subthemes and report on it in Section 3.1.2.

Table 2 highlights that we found very little literature relevant to our five research questions. As to R5 and the 340 tweets downloaded, no tweet used the terms “disabled” or “disability” or “disabilities” or “impair *” or related ones or other disability terms such as “autism”, “ADHD”, “deaf”, or “neurodiverse”.

3.1.1. Children and Youth with Disabilities

As to the mentioning of children and youth with disabilities, not one source covered children and youth with disabilities actions as activists within environmental activism (R1), the impact of children and youth environmental activism on children and youth with disabilities (R2), or environmental issues socially impacting children and youth with disabilities (subtheme 2, R3). One source covered the positive effects of the environment on children and youth with disabilities (R4), highlighting a project called “EcoRift” which offered virtual reality technology to provide mobility-impaired youth with access to nature sanctuaries [195]. The greatest amount (11 sources) of content we found in relation to R3, subtheme 1, indicated specific and unspecified environmental factors worsening or causing specified medical conditions or impairments in children or youth. The abstracts mentioned “hearing loss of young people” [196], “young people with malignant disease” [197] (p. S138), “on asthmatic Detroit teenagers” [198] (p. 323), “depressive disorders among young Canadians” [199], “Anxiety disorders in adolescence” [200] (p. 27), “mental health care-seeking among young adults” [201]. The abstracts provided statements like “young people have been recognized as experiencing higher rates of morbidity, disability, and mortality from various developmental, environmental, and behavioral risk factors than the general population” [202] (p. 243), “allergic rhinitis is one of the most frequent chronic diseases among children” investigating “environmental associated factors [203] (p. 530), “youths’ posttraumatic stress” [204] (p. 335) to be influenced by environmental factors [204] (p. 335). One stated: “Genes, environmental factors, and their interplay affect post-trauma symptoms, noting that although environmental predictors of the longitudinal course of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms are documented, there remains a need to incorporate genetic risk into these models, especially in youth who are underrepresented in genetic studies” [205] (p. 1).

3.1.2. Potentially Children and Youth with Disabilities

We identified some further content potentially fitting R1, R3, and R4 (not R2) in the sense that sometimes persons with disabilities were mentioned in a way that could also include children and youth with disabilities.

Within this content, four sources mentioned persons with disabilities in ways that could include children and youth with disabilities as environmental activists (R1). One source stated “the ‘bottom-up’ approach encourages participation of marginalized groups such as women, youth, and people with disabilities who bring diverse perspectives in content creation” [206] (p. 77).

A second source thematized the invisibility of deaf people and persons with disabilities in the environmental justice movement in South Wales (UK) [207] which could also cover deaf youth making the case “that in the UK and elsewhere little attention has been given to the way that disabled people may be excluded from environmental policymaking” [207] (p. 210) and that this is a reflection of the general lack of political engagement with persons with disabilities [207]. It makes the case that the involvement of persons with disabilities should not be “the disabled people” but take into account the variability of persons with disabilities whereby the authors focus on the case of deaf people [207]. As such, this could include deaf youth. The authors interviewed the local authorities and “local representatives of two important national environmental organizations (Friends of the Earth [FoE] and Black Environment Network [BEN])” [207] (p. 215) about their knowledge and perception of deaf people. The authors highlight that the local consultation process assumed a medical view of persons with disabilities including deaf people [207]. The authors made further the case that the organizations felt that more diverse groups of persons with disabilities, including deaf people, should be consulted, and that the organizations simply do not think about it but also that it would be logistically (money, time) an issue [207]. The authors also pointed out that knowledge in the deaf community is a problem as is the accessibility of environment activism events [207]. The authors conclude “environmental movement has yet to seriously engage with the political arguments and conceptual innovations associated with Deafness in particular, and the disability movement more generally” [207] (p. 218).

A third source stated “Ubuntu also locates disability politically within the wider environment and practices of sustainability which are now important to the post-2105 agenda, Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) and the (UN) Sustainable Development Goals linked to climate change” and that ubuntu includes “ukama, a feeling of relatedness or interdependence” which the author argues “includes the wider environment” [208] (p. 1) highlighting the problem of persons with disabilities being part of environmental action in a reality of “splintered rights activism” [208] (p. 4).

A fourth one covered Greta Thunberg, the founder of Fridays For Future, stating “Greta Thunberg, responding to ableist critics, insists that autism facilitates her climate activism and that “being different is a superpower” [209], but does not engage with the environmental activism of children and youth with disabilities. There were three sources that covered children and youth with disabilities and activism, but none covered environmental activism [210,211,212].

Three sources indicated environmental issues causing impairments (research question 3 subtheme 1); autism was mentioned as a negative consequence of air pollution [213] and two others linked ‘impairment’ to originate from an environmental problem [214,215].

Six sources engaged with the second sub-theme of research question 3 indicated environmental issues causing social issues for persons with disabilities. These six sources indicated that persons with disabilities are more vulnerable to heat-related diseases [216] and climate variability [217,218,219,220,221]. However, individuals with disabilities are mostly mentioned as part of a list of groups. One for example provided some data that persons with disabilities are often invisible in climate national adaptation policy documents using 20 health adaptation policy documents from 12 countries [220] stating that “health adaptation policy documents do not offer a well-developed basis for implementing national policy for the climate-vulnerable groups” [220] (p. 9). So, it only included persons with disabilities as part of a long list of groups they cluster under the term vulnerable groups.

In another source, authors gave data that 24.7% of interviewed participants see “the disabled” as the most vulnerable to climate variability and that “The disabled on the other hand are likely to be vulnerable because they are have limited opportunities and they experience discrimination by some of the family members and the community” [218] (p. 750).

One source covered the positive effects of the environment on persons with disabilities (R4) by highlighting how sustainability education students cared for persons with disabilities during farming activities [222] stating “how the care for disabled people could benefit for the regional land revitalization with small employment opportunities and observe the care practices conducted in the welfare sectors for the disabled people” [222] (p. 157).

4. Discussion

Out of 5487 abstracts obtained from strategies 1 and 2, none covered the actions of children and youth with disabilities as activists within environmental activism. One covered the ‘disability’ aspect of Greta Thunberg but did not engage with children and youth with disabilities and environmental activism. Three had content related to persons with disabilities and environmental activism that could be applied and could include children and youth with disabilities and three mentioned children and youth with disabilities in conjunction with activism but not environmental activism. None mentioned the impact of environmental activism on children and youth with disabilities or persons with disabilities. Fourteen mentioned children and youth with disabilities in the sense that the wordings indicated environmental factors ‘cause’ the ‘impairment’ in children and youth with disabilities. One suggested that the environment, as in nature, could be beneficial to children and youth with disabilities, and one made the same point using persons with disabilities in general which could also be applied to children and youth with disabilities. Six abstracts suggested that persons with disabilities are more impacted by environmental issues such as heatwaves and climate change, which could include children and youth with disabilities, but they were not explicitly mentioned. In the 49 abstracts and 19 downloaded full academic texts of articles obtained through strategy 3a that mentioned the youth movements “Youth4Climate”, “Fridays for Future”, “Extinction Rebellion”, “Student Strike 4 Climate” in the abstracts, children and youth with disabilities were not mentioned once. Finally, within the 340 downloaded “Fridays For Future” tweets from February 28-April 15, 2020, there was no mention of children and youth with disabilities or persons with disabilities in general. We discuss our findings in three sections: one using the lens of how the academic literature engaged with youth environmental activism, and the other section using the lens of empowerment theory. In the third section, we outline opportunities for our findings. In all three sections, we make use of ability-based concepts.

4.1. Youth Environmental Activism Narrative: Applicability to Children and Youth with Disabilities

The academic literature engages and argues for many different roles of youth in environmental activism [23,26,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56], such as being researchers [13,14,15,16,17], educators [18,19,20,21,22,23,24], catalysts of environmental change [223], environmentally considerate consumers [25,26], environmental stewards [224], and learners [225,226]. It is also noted that they should be influencers of environmental activism but often are not [59,60]. Children and youth with disabilities could also fulfill these environmental activism roles discussed in relation to youth. However, we found no engagement with them in any of these roles in the literature we covered, although they face many unique barriers to fulfill these roles. Some activism barriers for them mentioned in the activism literature in general are: (a) difficulties with physical access, such as access to protests and natural spaces where meetings were often held [123], (b) lack of accessible restrooms, inaccessible parking, no rest areas [95], (c) lack of accessible information, such as websites not being accessible to visually impaired participants, (d) lack of information relating to the accessibility of events, (e) financial and social barriers [123], and (f) barriers to online activism and protesting [95]. Although digital protest avenues, including online petitions and social media, represent new opportunities for persons with disabilities to become involved in activism, they also are not available to many persons with disabilities given that many persons with disabilities live in poverty and may not be able to utilize the technology that facilitates this way of action [95,117]. All these barriers should be engaged with in relation to children and youth with disabilities and environmental activism but are not according to our findings. Using the lens of ability expectation and ableism, one can reword this reality to say that these barriers reflect a form of ability privilege. If one has access to obtain certain abilities and exhibits certain abilities, one has the ability privilege to partake in environmental activism. The literature does not question this ability privilege as it does not question the inequity of being able to obtain certain abilities, for example, through access to education. As such, many studies are needed to provide the data necessary to enable children and youth with disabilities in the aforementioned roles and to eliminate barriers to their involvement in environmental activism.

It is noted in the literature covering youth environmental activism that environmental activism becomes part of the social activist identity for many youth [23,57], and the development of a youth environmental identity is engaged with [64]. Many of the role’s youth could have in environmental activism could become part of their identity as social activists or as active citizens. However, no article engaged with the identity formation of children and youth with disabilities in relation to environmental activism. Such lack is problematic given our findings that if the identity of children and youth with disabilities was indicated, it was a given medical identity as a negative outcome of environmental toxins and other environmental degradation [196,197,198,199,200,201,205,213,214,215]. Not one article that used this label for children and youth with disabilities questioned the use of this label, nor did any other article we covered. The dominance of the medical identity in the environmental problem and activism narrative fits with the concerns persons with disabilities voiced in other discourses. It has already been flagged by some that the environmental literature is heavily biased towards a deficiency frame of defining persons with disabilities [12,30,121,122,123,124,146]. In other words, the environmental literature decreases ability identity security, namely that one can feel at ease with one’s abilities. Indeed this prevailing accepted medical imagery is often used to weaponize the image of persons with disabilities, like how the negative ‘disability’ imagery is used to discredit the environmental activism of persons with disabilities (see for example the environmental activist Greta Thunberg, who self-identifies as having Asperger’s Syndrome [4,227] and whose Asperger label has been used to discredit her in response to which she labelled Asperger’s to be a “superpower” [227]). The use of negative imagery surrounding persons with disabilities and the objectification of persons with disabilities in which their role is linked to negative imagery is a prime example of the importance of how one is identified by others and how one self-identifies. In environmental activism, the negative imagery of persons with disabilities, including children and youth with disabilities, and the narrow role narratives of persons with disabilities, including children and youth with disabilities, might discourage children and youth with disabilities from engaging in environmental activism and action [227,228]. Indeed, although not covering children and youth with disabilities and environmental activism as such, in two consultations with disability groups covering sustainability issues many stated that the medical imagery of persons with disabilities was one reason why persons with disabilities are left out of policy discussions [114,115,116]. It is stated that “young people’s search for connection and safety (belonging), visibility and respect (recognition) within their communities shapes their self-understanding and horizons for action” [229]. Our findings do not provide any data that this search is successful for children and youth with disabilities in relation to environmental actions and shows that activism as an identity is an area that needs more exploration, given the negative social realities children and youth with disabilities face.

As to children and youth with disabilities being social actors, being seen as a social actor is “affected by a combination of three factors: conflicts and dilemmas within current policy; social constructions of disabled children; and power as a barrier to participation” [230]. Indeed, if disability is constructed as a medical issue, what should children and youth with disabilities be involved in? To quote from one study that identifies many problems children and youth with disabilities face in relation to participation:

“Compared to their non-disabled peers, disabled children and young people experience multiple discrimination, low expectations, and social exclusion (Russell 2003). Further to this, as Davis et al. (2005) argue, ‘policy decisions rarely take account of disabled children’s opinions because professional practices and vested interests of service providers are promoted before those of children’, meaning that disabled children’s ‘needs’ are often primarily defined by non-disabled adults’ perceptions of what they ‘need’ (ibid.). Hence, policy is often shaped by non-disabled adult assumptions, prejudices, or stereotypes about disabled children and young people. Policies and structures that are developed for all children and young people often fail to consider the needs and opinions of disabled children and young people, rendering them inaccessible and not inclusive. For example, mainstream participation structures tend to be exclusive of disabled children and young people, often utilizing inaccessible participation methods” [231] (p. 100–101).

The identity bias is a reminder that “disabled children experience discrimination and oppression on the grounds not only of being children, but also of being disabled” [230] (p. 100) and the negative social attitudes [232] towards them. Framing the disability topic as medical very likely negates the possibility for children and youth with disabilities to fulfill the demand that:

“child participation must be authentic and meaningful. It must start with children and young people themselves, on their own terms, within their own realities and in pursuit of their own visions, dreams, hopes and concerns” [233].

Malone and Hartung state one of the most effective strategies for creating better cities is through the actual process of participation: (a) helping young people to listen to one another, (b) to respect differences of opinion, (c) to find common ground, (d) to develop their capacities for critical thinking, (e) to evaluate and reflect, (f) to support their processes of discovery, (g) awareness building, (h) collective problem- solving, and (i) helping them to develop the knowledge and skills for making a difference in their world [231]. If children and youth with disabilities are not present or if the narrative is mostly focused on eliminating ‘impairments’, how can the process of participation be achieved?

Many articles in the youth environmental activism-focused academic literature state that youth are impacted by environmental issues in their social reality [15,65,66,67,68]. In the literature we covered, we found no such angle of coverage in relation to children and youth with disabilities, and not one article looked at this aspect as a target for environmental activism despite the fact that persons with disabilities, including children and youth with disabilities, are disproportionally negatively impacted by environmental events like natural disasters and extreme temperatures due to social and environmental barriers [125,126].

Another essential aspect to consider is how environmental action and discourses affect children and youth with disabilities, something we did not find in our literature. Besides protests interrupting the often hard to obtain transport necessary for persons with disabilities [234] which includes children and youth with disabilities, environmental action has also impacted persons with disabilities, including children and youth with disabilities, through banning necessities central to their lives [11]. One such conflict is around the ban of single-use plastic straws [11]. While many environmental activists rejoiced these bans, persons with disabilities including children and youth with disabilities, who often need disposable straws due to their positionality, low cost, low risk of allergy, choking, and injury, and sanitariness compared to available alternatives, were outraged and lashed back with social media campaigns like #SuckItAbleism, intended to highlight the necessity of disposable straws [11]. Further, while it is important to not exploit deaths like these to further agendas, activists’ with disabilities worst fears were highlighted when a 60-year-old disabled woman, Elena Struthers-Gardner, died after falling on her metal straw [235]. Many other demands of environmental activism that impact persons with disabilities including children and youth with disabilities differently than the general population. However, with no engagement with children and youth with disabilities in environmental activism and with environmental activists having no exposure to children and youth with disabilities, environmental activists very likely are not aware of the consequences their demands and actions have on persons with disabilities including children and youth with disabilities. This unawareness stems from the low literacy of persons and youth without disabilities on the reality of persons with disabilities including children and youth with disabilities.

Finally, many articles in the youth environmental activism academic literature mention competencies needed by youth as environmental activists [69,70,71,72]. If we look at the many competencies and abilities needed to be part of environmental activism as children and youth, most of these competencies and abilities pose specific challenges for children and youth with disabilities and need a differentiated engagement with children and youth with disabilities.

Moving beyond the general youth environmental activism coverage, the academic coverage of “Youth4Climate” OR “Fridays for Future” OR “Extinction Rebellion” OR “Student Strike 4 Climate” also ignores the role of children and youth with disabilities in these movements. Given that non-academic sources are highlighting the problem of “Youth4Climate” OR “Fridays for Future” OR “Extinction Rebellion” OR “Student Strike 4 Climate” in relation to children and youth with disabilities [234,236,237], one can conclude that the academic discourse is problematic in ignoring the children and youth with disabilities aspects of youth environmental activist groups coverage.

Finally, moving beyond academic literature, it is also troubling that the tweets we investigated from “Fridays for Future” did not mention children and youth with disabilities or persons with disabilities at all.

4.2. Lack of Empowerment of Children and Youth with Disabilities

Applying empowerment theory [154] to children and youth with disabilities suggests that they should have an active role in the change process [169,172,173]. Our data suggest that the academic discourse around youth environmental activism disempowers children and youth with disabilities as environmentalism change agents. Various indicators and attributes of empowerment exist [63,165,166,167,168] including some for youth empowerment, such as the Sociopolitical Control Scale for Youth (SPCS-Y) [169], and for the empowerment of persons with disabilities [153]. These indicators and attributes of empowerment could have been used and can be used to further the empowerment of children and youth with disabilities in environmental discourses and activism. According to empowerment theory, there are four categories of empowerment: (a) psychological empowerment, (b) organizational empowerment, (c) community empowerment, and (d) relational empowerment [174]. Our findings suggest that the youth environmental activism-focused academic discourse facilitates relational and community disempowerment of children and youth with disabilities by ignoring them. Psychological empowerment includes the belief that one has the ability to influence sociopolitical and other aspects of one’s life as well as the competency of recognizing and understanding the sociopolitical environment and what one needs to achieve one’s goal (such as knowledge) [169]. Our data suggest that children and youth with disabilities are not seen within this framework of competency and therefore are disempowered.

Five factors have been identified for empowerment: (a) self-efficacy/self-esteem, (b) power-powerlessness, (c) community activism, (d) righteous anger, and (e) optimism-control over the future [165]. All of them could be used as lenses to critically analyze the relationship between children and youth with disabilities and environmental activism by children and youth.

According to empowerment theory, the following parameters are needed to empower youth:

“(1) a welcoming, safe environment, (2) meaningful participation and engagement, (3) equitable power-sharing between youth and adults, (4) engagement in critical reflection on interpersonal and sociopolitical processes, (5) participation in sociopolitical processes to affect change, and (6) integrated individual- and community-level empowerment” [154].

One can make a case that children and youth with disabilities pose specific challenges to fulfill all these parameters in youth activism including youth environmental activism due to the many physical, economic, attitudinal, and other barriers they experience in their life [95,117,123,238,239]. As such, one should identify and engage with these challenges. If these parameters are not attainable for children and youth with disabilities in environmental movements, it may discourage their participation.

It is recognized that empowerment processes and outcomes are depending on the context they are used in and the people targeted [63,180,181] and shift over time [177]. Children and youth with disabilities live within a very specific context and, as such, one must engage and understand their empowerment experiences. The existing literature fails to contribute to increasing this understanding. Empowerment is about gaining control over one’s life and being able to influence the change process and the parameters including sociopolitical parameters, such as leadership competence and policy control, that affect one’s life [63,169,240]. Our data suggest that children and youth with disabilities are not thought about in this way. Empowerment is associated with the demand to question oppression as “structural oppression impacts individuals and hampers their ability to control their lives, which in turn influences their ability to participate fully in economic, social and political processes” [170]. Given this view, academic discourses around children and youth environmental activism add to structural oppression.

4.3. Many Opportunities

Our problematic findings around children and youth with disabilities and environmentalism fits well with the problems faced by persons with disabilities in relation to environmental activities mentioned by others [241,242], including their invisibility in relation to other environmental discourses such as the “deep ecology movement” [31] (p. 45). This all suggests a disempowerment of children and youth with disabilities and persons with disabilities.

Fenney quotes one participant in her study on ableism and disablism in the UK environmental movement as follows:

“Unless we can get disabled people working and integrating in the core fabric of the environmental sector, we’re not gonna be able to make these connections and the world is not gonna see how environmental justice and inclusion is linked so closely to disability equality and inclusion” [123] (p. 518).

However, the reality also presents a vast opportunity to enrich environmental activism in general and children and youth environmental activism. Particularly, we suggest that exposing youth environmentalism to the ability-based expectations, judgments, norms, and conflicts children and youth with disabilities experience every day as part of their lived experience and ability based concepts such as ability expectation, ableism [27,133,243,244,245,246,247,248,249,250], eco-ability [31,32,33,34,35,150], eco-ableism [29], and eco-crip theory [147] used in academic literature is beneficial to youth environmental activism. Furthermore, youth environmental activism can make use of the already existing ability-based discussions using various ability-based concepts around the human–nature relationship [30,36,122,134,135] and environmental issues [11,12,102,123,124,138,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149]. Energy policies are at the core of environmental activism, and the concepts of ability expectation and ableism have been used as a system analysis tool to dissect energy security and energy insecurity [102]. Different ability expectations among different groups are noted as one reason for slow progress in international agreements on climate change and the move to non-carbon-based energies [8,102], as is the difference in ability expectations people have of nature that adhere to anthropocentric versus bio/ecocentric frameworks [30,102]. These ability expectation differences, the hierarchy of ability expectations, and the issue of who has the power to move their ability expectations up the hierarchy are all dynamics that impact environmental activism. Various ability-based concepts are highly useful for environmental activism; for example “ability privilege describes the advantages enjoyed by those who exhibit certain abilities and the unwillingness of these individuals to relinquish the advantage linked to the abilities” [122] (p. 118). When Desmond Tutu questions adaptation apartheid [251], it is about people of power defending the status quo of their ability privileges, such as how they use natural resources to support the abilities they are used to and that the ones with the power expect others to adapt to the negative consequences these others experience. One could call this also ability expectation and ableism apartheid [252]. When Desmond Tutu writes about adaptation apartheid, he writes about an ability injustice as in “the disablism (the lack of support and active disablement by the ones who see themselves as able)” [17] (p. 43) driven by ability privilege. Desmond Tutu gives voice to the reality of ability inequity, “a normative term denoting an unjust or unfair distribution of access to and protection from abilities generated through human interventions” [250] (p. 99) and ability inequality, “a descriptive term denoting an uneven access to and protection from abilities generated through human interventions” [250] (p. 99). Many people push for green consumerism, which is questioned as being linked to race and class privilege [253], but it is also reflecting an ability privilege, namely the ability for green consumption [122]. When people question the use of plastic straws, which in turn is questioned by persons with disabilities [10,11], one could say that the ones with the ability privilege of being able to do the same action without a plastic straw make this the ability norm and, with that, disable the ones who do not have this ability privilege. Green consumerism, the plastic straw, and Desmond Tutu questioning adaptation apartheid are just three examples of ability-based conflicts between groups.

System thinking is viewed as important in many fields, including the eco-health field [254]. Ability expectation, ableism, eco-ability, eco-ableism, and eco-crip theory are all system-level concepts allowing for the analysis of systems based on ability expectations.

Mapping out ability expectations of different groups in relation to nature allows environmental activism to flag ability-related conflicts between groups and would make visible the ability privileges of certain groups over others. They allow for foresight in what environmental activism must deal with in the future; for example, to analyze the relationship between artificial intelligence (non-sentient and sentient, if that ever comes to pass) and humans, animals, and nature. It also allows for the analysis of moves to make animals sentient to enhance their status in relation to humans.

5. Conclusions

The findings from our study suggest that current academic literature surrounding children and youth environmental activism rarely engaged with children and youth with disabilities. If the literature covered mentioned children and youth with disabilities, the focus was upon the environment causing/worsening ‘impairments’, yet did not at all mention them engaging in the action as activists in environmental activism or the impact of environmental activism on them. Our findings fit with other studies that question the missing involvement of children and youth with disabilities in activism and policy-making (see for example [230,255]) and with the well-known fact that evidence is missing around the social situation of persons with disabilities [97,98,99,111,256,257], which includes children and youth with disabilities.

Our findings are problematic, as persons with disabilities, including children and youth with disabilities, are impacted by environmental issues [8,125,126,127,128] and by environmental activism [11], and therefore both persons with disabilities in general and children and youth with disabilities, in particular, have a stake in these matters, and children and youth with disabilities should be engaged with in youth environmental activism. Our scoping review suggests that the literature covered is deeply disempowering for children and youth with disabilities and that youth environmental movements do not make use of the expertise of children and youth with disabilities, including their lived experience of ability-based expectations, judgments, norms, and conflicts.

If one would do a study on the items of the Sociopolitical Control Scale for Youth (SPCS-Y), our results suggest many of the questions would be answered in a negative way by children and youth with disabilities in relation to their role in environmental activism and the impact of environmental activism on them [169]. Reasoning strategy favors one’s in-group [258]. Our findings do not suggest that children and youth with disabilities are in the in-group and as such, the question arises what is reasoned in between the in-group? “Allies refers to ‘members of dominant social groups (e.g., in some cases this might be men, heterosexuals or white people) who are working to end the system of oppression that gives them greater privilege and power based upon their social group membership” [259] (p. 357). Our findings suggest that children and youth with disabilities are not part of the core group and do not seem to be filling the ally’s category either.

Given the results of the study, future research should be conducted in relation to children and youth with disabilities participating as activists in environmental activism. Given the already identified impacts of environmental activism on children and youth with disabilities (see the prohibition of straws [10,235]) and the fact that we could not find one article engaging with the impact of environmentalism on them, it is warranted to investigate and map out in a much more cohesive way the impact of environmental activism on them. Involving the opinions and experiences of children and youth with disabilities in future research may allow researchers to better portray the lives and struggles of children and youth with disabilities who want to be/are involved in environmental activism and the impact of environmental activism on children and youth with disabilities. Given that ability expectations of people are often at the root of environmental problems, the conflicts between groups including humans and nature [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36], and that the very concept of ability expectation and its impact are at the core of disability rights discourses and the lives of children and youth with disabilities, children and youth with disabilities have a unique contribution to make to environmental activism and the resulting ability expectation conflicts between groups. Our findings also have implications for the education system. In two consultations covering sustainability issues, many concrete actions from academics and academic institutions were outlined [114,115,116]. These actions could be applied to demand an engagement with children and youth with disabilities and environmental impact and activism in the educational system on the teaching, research, and civic engagement level. Finally, one may wonder whether our findings are a symptom of non-functioning equity/equality, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) strategies for persons with disabilities in universities [260] and whether an improvement in EDI realities in universities for students, academic, and non-academic staff with disabilities might lead to changes in the research topics chosen in relation to persons with disabilities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.W. and C.S.; methodology, C.S. and G.W.; formal analysis, C.S. and G.W.; investigation, C.S. and G.W.; data curation, C.S. and G.W.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S. and G.W.; writing—review and editing, C.S. and G.W.; supervision, G.W.; project administration, G.W. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Asmelash, L. Greta Thunberg Isn’t Alone. Meet Some Other Young Activists Who Are Leading the Environmentalist Fight. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2019/09/28/world/youth-environment-activists-greta-thunberg-trnd/index.html (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Connect4Climate. Youth4Climate: They Are Our Future. Available online: https://www.connect4climate.org/initiatives/youth4climate (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Connect4Climate. Inspiring Youth to Engage in the Climate Discussion: #Youth4Climate. Available online: https://www.connect4climate.org/initiative/inspiring-youth-engage-climate-discussion-youth4climate (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Fridays for Future. Who We Are. Available online: https://fridaysforfuture.org/what-we-do/who-we-are (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Fridays for Future. Strike Statistics. Available online: https://fridaysforfuture.org/what-we-do/strike-statistics (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Jhanji, H.; Sarin, V. Relationship between environmental consciousness and green purchase behaviour among youth. Int. J. Green Econ. 2018, 12, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. United Nations 2018 Flagship Report on Disability and Development: Realization of the Sustainable Development Goals by, for and with Persons with Disabilities. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/publication-disability-sdgs.html#:~:text=%E2%80%9CThe%20UN%20Flagship%20Report%20on,can%20create%20a%20more%20inclusive (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Wolbring, G. A Culture of Neglect: Climate Discourse and Disabled People. J. Media Cult. 2009, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjord, L.; Manderson, L. Anthropological perspectives on disasters and disability: An introduction. Hum. Organ. 2009, 68, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A. The Rise and Fall of the Plastic Straw Sucking in Crip Defiance. Catal. Fem. Theory Technosci. 2019, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenks, A.B.; Obringer, K.M. The poverty of plastics bans: Environmentalism’s win is a loss for disabled people. Crit. Soc. Policy 2020, 40, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.J. The Ecological Other: Environmental Exclusion in American Culture; University of Arizona Press: Tuscon, AZ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, E.J.; Staples, K.; Reed, M.G.; Carriere, R.; MacColl, I.; McKay-Carriere, L.; Fresque-Baxter, J.; Steelman, T.A. Insights for Building Community Resilience from Prioritizing Youth in Environmental Change Research. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, H.L.; Dixon, C.G.; Harris, E.M. Youth-focused citizen science: Examining the role of environmental science learning and agency for conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 208, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickle, M.B.; Evans-Agnew, R. Photovoice and youth empowerment in environmental justice research: A pilot study examining woodsmoke pollution in a Pacific Northwest Community. J. Community Health Nurs. 2017, 34, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxton, C.A. Social problem solving through science: An approach to critical, place-based, science teaching and learning. Equity Excell. Educ. 2010, 43, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans-Agnew, R.A.; Eberhardt, C. Uniting action research and citizen science: Examining the opportunities for mutual benefit between two movements through a woodsmoke photovoice study. Action Res. 2019, 17, 357–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delp, L.; Brown, M.; Domenzain, A. Fostering youth leadership to address workplace and community environmental health issues: A university-school-community partnership. Health Promot. Pract. 2005, 6, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurancha, P.; Inkapatanakul, W.; Chunkao, K. Guidelines to the management of firefly watching tour in Thailand. Mod. Appl. Sci. 2013, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Younan, S.; Jenkins, J. Reality Check: Adding Plastic to Natural History. J. Mus. Educ. 2020, 45, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Cherry, L. Enlisting the power of youth for climate change. Am. Psychol. 2019, 75, 945–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, A.; Easton, J.; Murthy, R.; Davidson, E.; De Bruijn, J.; Hayse, T.; Hens, E.; Lloyd, M. Helping Engineering and Science Students Find Their Voice: Radio Production as a Way to Enhance Students’ Communication Skills and Their Competence at Placing Engineering and Science in a Broader Societal Context. Available online: https://peer.asee.org/helping-engineering-and-science-students-find-their-voice-radio-production-as-a-way-to-enhance-students-communication-skills-and-their-competence-at-placing-engineering-and-science-in-a-broader-societal-context (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Cintrón-Moscoso, F. Cultivating Youth Proenvironmental Development: A Critical Ecological Approach. Ecopsychology 2010, 2, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exner, D.N.; Cárdenas-Alpuche, J. Borrowing Teaching and Research Tools for a Network of Water Monitoring and Education in Mexican High Schools. Nat. Sci. Educ. 2014, 43, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanomi, A.; Luppi, F. A European Mixed Methods Comparative Study on NEETs and Their Perceived Environmental Responsibility. Sustainability 2020, 12, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, L.C.R.; Hewege, C.R. Climate change risk perceptions and environmentally conscious behaviour among young environmentalists in Australia. Young Consum. 2013, 14, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbring, G. Ability Expectation and Ableism Literature. Available online: https://wolbring.wordpress.com/ability-expectationableism-literature (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Wolbring, G.; Deloria, R.; Lillywhite, A.; Villamil, V. Ability Expectation and Ableism Peace. Peace Rev. 2020, 31, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbring, G. Eco-Ableism. Available online: https://svara98.typepad.com/blog/2012/09/eco-ableism-anthropology-news.html (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Wolbring, G. Ecohealth through an ability studies and disability studies lens. In Ecological Health: Society, Ecology and Health; Gislason, M.K., Ed.; Emerald: London, UK, 2013; Volume 15, pp. 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Wolbring, G.; Lisitza, A. Justice Among Humans, Animals and the Environment: Investigated Through an Ability Studies, Eco-Ableism, and Eco-Ability Lens. In Weaving Nature, Animals and Disability for Eco-Ability: The Intersectionality of Critical Animal, Disability and Environmental Studies; Nocella, A.J., II, George, A.E., Schatz, J.L., Eds.; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2017; pp. 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Various. Earth, Animal, and Disability Liberation: The Rise of the Eco-Ability Movement; Nocella, A.J., II, Bentley, J., Duncan, J.M., Eds.; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Eco-Ability Facebook Group Members. Eco-Ability: Animal, Earth and Disability Liberation. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/groups/ecoability (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Bentley, J.K.; Conrad, S.; Hurley, S.; Lisitza, A.; Lupinacci, J.; Lupinacci, M.W.; Parson, S.; Pellow, D.; Roberts-Cady, S.; Wolbring, G. The Intersectionality of Critical Animal, Disability, and Environmental Studies: Toward Eco-Ability, Justice, and Liberation; Lexington Books: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nocella, A.J., II. Defining Eco-Ability. In Disability Studies and the Environmental Humanities; Ray, S.J., Sibara, J., Eds.; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2017; pp. 141–168. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts-Cady, S. Exploring Eco-Ability. In The Intersectionality of Critical Animal, Disability, and Environmental Studies: Toward Eco-ability, Justice, and Liberation (Critical Animal Studies and Theory); Nocella, A.J., II, George, A.E., Schatz, J.L., Eds.; Lexington Books: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, D.G.; Feighery, E.C. Future directions for youth empowerment: Commentary on application of youth empowerment theory to tobacco control. Health Educ. Behav. 2004, 31, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, R. The First Green Wave: Pollution Probe and the Origins of Environmental Activism in Ontario; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Longhurst, J. “Typically American” Trends in the History of Environmental Politics and Policy in the Mid-Atlantic Region. Pa. Hist. 2012, 79, 409–427. [Google Scholar]

- Sheoran, B. Ecofeminism, Nascent Critical Approach: An Analysis of Fire on the Mountain. Int. J. Online Humanit. 2015, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, S.P. A History of Environmental Politics since 1945; University of Pittsburgh Press: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rootes, C. Environmental movements: From the local to the global. Env. Polit. 1999, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K.; Selboe, E.; Hayward, B.M. Exploring Youth Activism on Climate Change: Dutiful, Disruptive, and Dangerous Dissent. Available online: https://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol23/iss3/art42 (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Feinberg, M.; Willer, R. The moral roots of environmental attitudes. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pryor, A.; Carpenter, C.; Townsend, M. Outdoor education and bush adventure therapy: A socio-ecological approach to health and wellbeing. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2005, 9, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, C.D.; Profice, C.C.; Collado, S. Nature Experiences and Adults’ Self-Reported Pro-environmental Behaviors: The Role of Connectedness to Nature and Childhood Nature Experiences. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buttigieg, K.; Pace, P. Positive youth action towards climate change. J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 2013, 15, 15–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, K.; Lousley, C. Girls Just Want to Have Fun-With Politics. Altern. J. 2001, 27, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, H.R. We Fight to Win: Inequality and the Politics of Youth Activism; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Partridge, E. From ambivalence to activism: Young people’s environmental views and actions. Youth Stud. Aust. 2008, 27, 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira Paz, D.; Gaspareto Higuchi, M.I. Origem do Interesse, Motivação e Preocupação Ambiental em Jovens Engajados Socioambientalmente na Região Metropolitana de Manaus-AM. Available online: https://periodicos.unb.br/index.php/sust/article/view/16711 (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Schusler, T.; Krings, A.; Hernández, M. Integrating youth participation and ecosocial work: New possibilities to advance environmental and social justice. J. Community Pract. 2019, 27, 460–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schusler, T.M.; Krasny, M.E.; Peters, S.J.; Decker, D.J. Developing citizens and communities through youth environmental action. Environ. Educ. Res. 2009, 15, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schusler, T.M.; Krasny, M.E.; Decker, D.J. The autonomy-authority duality of shared decision-making in youth environmental action. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 533–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, I.R.d.; Neves, A.L.M.d.; Callegare, F.P.P.; Higuchi, M.I.G.; Pereira, E.C.F.F. Experiences of environmental leadership by young people: Implications for the constitution of the ethical-political subject. Trends Psychol. 2018, 26, 617–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skogen, K. Young Environmentalists: Post-modern identities or middle-class culture? Sociol. Rev. 1996, 44, 452–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, D.; Pe’er, S.; Yavetz, B. Environmental literacy of youth movement members–is environmentalism a component of their social activism? Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 486–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnein, A.; Roser, D. Saving the planet by empowering the young? In Youth Quotas and Other Efficient Forms of Youth Participation in Ageing Societies; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 77–92. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, E.; Skovdal, M.; Campbell, C. Ethiopian students’ relationship with their environment: Implications for environmental and climate adaptation programmes. Child. Geogr. 2013, 11, 436–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, H.; Limb, M.; Taylor, M. Young people’s participation and representation in society. Geoforum 1999, 30, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]