Exploring the Relationship between Leisure and Sustainability in a Chinese Hollow Village

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The relation between Leisure and Sustainability

1.2. The Phenomena of Hollow Villages in China

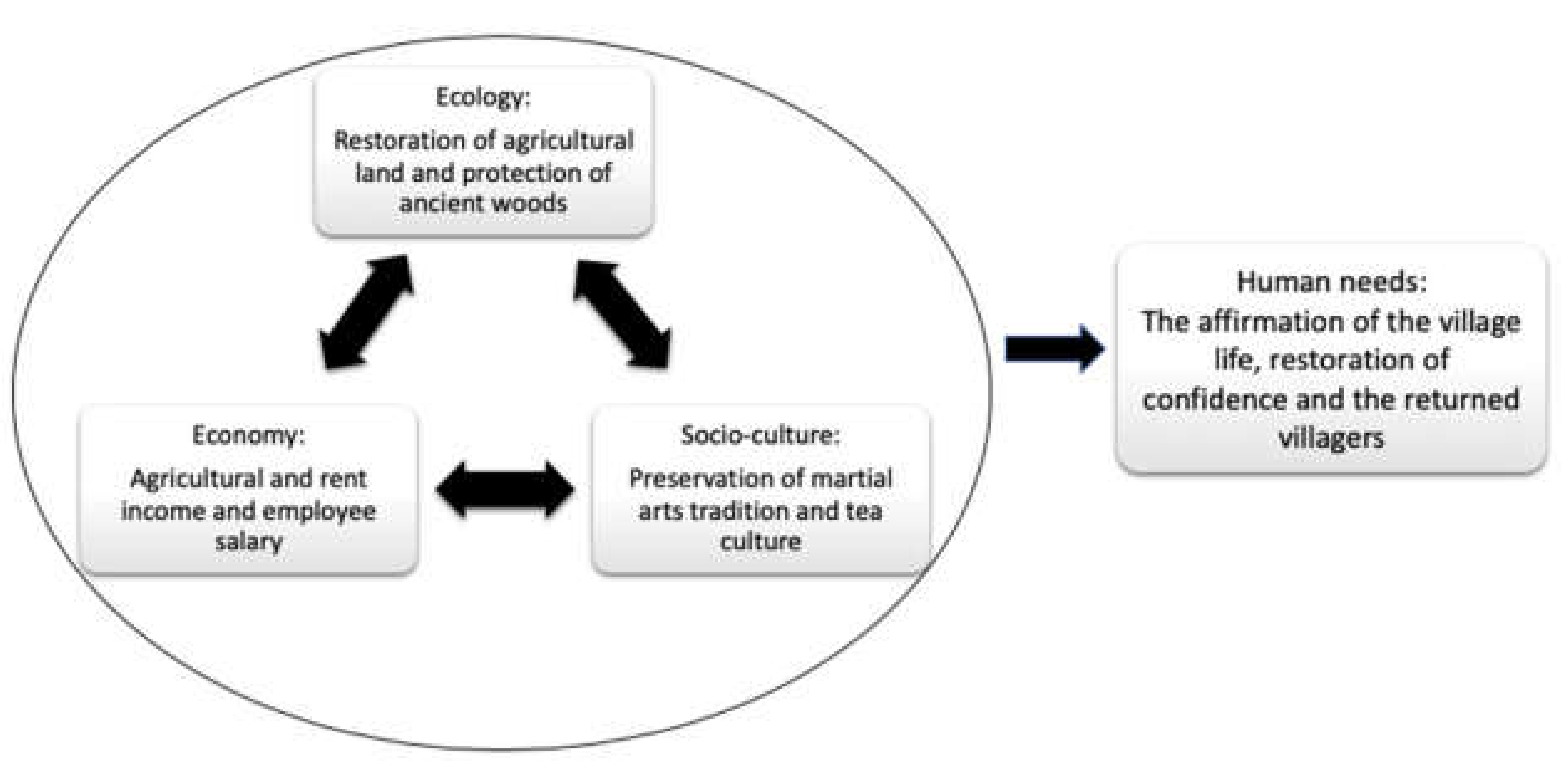

2. Theoretical Framework: A Comprehensive Model of Sustainability

2.1. The Dual Model: Weak and Strong Sustainability

2.2. A comprehensive Model: Combining the Weak and Strong Sustainability

3. The Research Context: The Tea Village and the Leisure Program

4. Methods

4.1. Data Collection

4.1.1. Fieldwork

4.1.2. Focus Group Interviews

4.1.3. Data Analysis

5. Findings

5.1. Ecological, Economic and Socio-Cultural Aspects of Sustainability through the Program’s Recreational Agricultural Activities

Just have a glance outside. The advantage of it (the ecological aspect) is obvious. I first came here at the end of 2016 and a few days ago, the local officials have taken me to see other places, one village after another. On the way here, we drove through mountainous areas and the roads were not good, so no factories and industries, but that protected the entire ecology, natural environment, the mountain and its vegetation. … All along the way, I’ve been in such scene: a long road, on one side, is a stream and on the other side is the mountain.

When I came here, what struck me most about this village was the ancient woods. … I found that when I stood in these woods, I felt I was breathing through, living in and surrounded by thousands of years of time and space. I don’t know how to measure the value with money and how to evaluate its price. I think those elites who live in cities would understand the value of it.

Once, there’s a pine tree in the middle of the woods. The pine was bigger and taller than other trees. It was a village bully, who cut the pine down and sold it. Afterwards, something very dangerous happened here. A plague hit our village and nine out of the 11 or 12 children died. … we are still calling this patch of ancient trees—the Pine Woods. We think our ancient trees cannot be moved or cut. If any of these ancient trees die, unfortunate events would occur in the village. We truly think that way. That’s why the ancient woods could be protected. Now, no one dares to harm the trees. It’s really powerful and spiritual.

Last year we designed a program called ‘Spring Ploughing’. Villagers helped to grow corns, rape seed flowers, rice and other things (in the company rented agricultural land) and send our members living in cities the agricultural products, such as cornmeal, vegetable oil, chestnuts, dry vegetables.

This year we upgraded the program and named it ‘the Dining Plan’. Our members in the cities wanted to eat seasonal food, so we sent them free-ranged chickens and eggs during the Chinese New Year. In March, we sent them spring bamboo shoots. Now we are making green tea and vegetable oil to send to them.

You can see the village’s original texture and its ecological way of life haven’t been changed. When we first came to the village, the houses were a little shabby and some walls were collapsed, we only did the minimum repair of the walls, so the original look of the village was retained. It’s still a typical small mountain village in this area and we think this’s very valuable.

5.2. Economic, Socio-Cultural and Ecological Aspects of Sustainability through Program’s Promotion of the Traditional Martial Arts

Nonemployee-villager 1: My father was a famous martial arts master in this village. He used to tell me we must pass down our martial arts and my village has been always like that. We take ancestral teachings and ways of doing things seriously. Our ancestors said the Luo family’s staff fighting techniques must be passed down and my father said to me I could forget about everything except our martial arts, especially the staff fighting techniques.

Nonemployee-villager 2: My great grandfather said the same. He told us we shouldn’t let our martial arts disappear. We must hand it down to the next generation.

In the past, when the village wasn’t busy with farming, we would all gather together to learn martial arts. We also practiced with the 24 solar terms, and especially on the day of the Lunar New Year, the whole village practiced together. Unlike nowadays, in the past, martial arts training was very harsh. And only passed down to men, not to women. The girls in the village weren’t allowed to practice.

It’s changed, not like before. We all learn and practice (martial arts) together. Old folks were concerned and told us not to teach everything we know to outsiders. They were afraid that people from outside learn everything we know and the martial arts wouldn’t?? be ours. The old folks still have such concerns and constantly came to us to say what we can and can’t teach to outsiders.

I think we shouldn’t only teach our own people. If people from outside came to learn, we also should teach them. Especially now, martial arts are integrated into sports and can help to build up physical fitness. Now we need to spread the essence of our martial arts to other places, even though our ancestors made the rules of not teaching women, but those’re outdated ideas. Now people are more open-minded and want to be healthier and fitter through martial arts practices. I wish our martial arts can be learned by more and more people.

5.3. The Comprehensive Sustainability and the Needs of the Villagers

The guests would have meals and activities at there (the ancient woods). We all gathered there. The guests especially loved to be there and they played erhu and flute in the woods. They also sat there having afternoon tea. Some of them also practice Kung Fu swords there.

The most valuable legacy of this program is not leaving villagers with renovated houses or increased income, but letting them acknowledging their way of life is as equal good to the life in the cities. At the beginning of this program or many years before this program, villagers thought their way of life was completely left behind from urban life. They didn’t think their things are beautiful and valuable.

We have stayed in the town for more than 20 years. Until the company and its leisure program came to the village and they started hiring people, I moved back to the village and worked at the program. I helped to clean the guest houses. I like working at the program and my husband also moved back. We both work here. Here, we have rent income, work income and our household income and life are getting much better.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, Z.P. China’s Rural Population Hollowizing and Its Challenge. Popul. Res. 2008, 32, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, Y.N. Family Migration Pattern in China. Popul. Res. 2014, 38, 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.M. Researches on the China’s Rural Vitalization Strategy from Several Dimensions. Reform 2018, 289, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Vaugeois, N.; Parker, P.; Yang, Y. Is leisure research contributing to sustainability? A systematic review of the literature. Leisure Loisir 2017, 41, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L. Empirical Evidence of the Contributions of Leisure Services to Alleviating Social Problems: A Key to Repositioning the Leisure Services Field. World Leis. J. 2008, 50, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neo, H. Sustaining the unsustainable? Golf in urban Singapore. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2001, 8, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Shen, H.; Law, R.; Chau, K.Y.; Wang, X. Examination of Chinese Tourists’ Unsustainable Food Consumption: Causes and Solutions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brightbill, C.K. The Challenge of Leisure; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Dumazedier, J. Leisure and the social system. In Concepts of Leisure; Murphy, J.F., Ed.; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1974; pp. 129–144. [Google Scholar]

- De Grazia, S. Of Time, Work, and Leisure; Anchor Books: Garden City, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins, R. When leisure engenders health: Fragile effects and precautions. Ann. Leis. Res. 2021, 24, 430–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spracklen, K.; Lashua, B.; Sharpe, E.; Swain, S. (Eds.) Introduction to the Palgrave Handbook of Leisure Theory. In The Palgrave Handbook of Leisure Theory; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017; Volume 6, pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, J.R. Work and Leisure: A Simplified Paradigm. J. Leis. Res. 2009, 41, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stebbins, R.A. Leisure as not work: A (far too) common definition in theory and research on free-time activities. World Leis. J. 2018, 60, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purrington, A.; Hickerson, B. Leisure as a cross-cultural concept. World Leis. J. 2013, 55, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spracklen, K. Constructing Leisure: Historical and Philosophical Debates; Palgrave MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Godbey, G. Leisure in Your Life: An Exploration; Venture Publishing Inc.: State College, PA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, J.; Gao, J.; Zhang, C. Food Heritagization and Sustainable Rural Tourism Destination: The Case of China’s Yuanjia Village. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kellison, T.B.; Hong, S. The adoption and diffusion of pro-environmental stadium design. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2015, 15, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, B.P.; Orr, M.; Kellison, T. Sport Ecology: Conceptualizing an Emerging Subdiscipline Within Sport Management. J. Sport Manag. 2020, 34, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallen, C.; Adams, L.; Stevens, J.; Thompson, L. Environmental Sustainability in Sport Facility Management: A Delphi Study. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2010, 10, 367–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, B.P.; Orr, M.; Watanabe, N.M. Measuring Externalities: The Imperative Next Step to Sustainability Assessment in Sport. J. Sport Manag. 2020, 34, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, M.; Inoue, Y. Sport versus climate: Introducing the climate vulnerability of sport organizations framework. Sport Manag. Rev. 2018, 22, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trendafilova, S.; McCullough, B.P. Environmental sustainability scholarship and the efforts of the sport sector: A rapid review of literature. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2018, 4, 1467256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundtland, G.H. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. 20 March 1987. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2020).

- Jiang, S.J.; Luo, P. A Literature Review on Hollow Villages in China. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2014, 24, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Liu, Y.; Xu, K. Hollow villages and rural restructuring in major rural regions of China: A case study of Yucheng City, Shandong Province. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2011, 21, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.S.; Liu, Y.; Zhai, R.X. Geographical Research and Optimizing Practice of Rural Hollowing in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2009, 64, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, W.G.; Li, Y.R.; Liu, Y.S. Rural hollowing in key agricultural areas of China: Characteristics, mechanisms and countermeasures. Resour. Sci. 2011, 33, 2014–2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.S. Research on the urban-rural integration and rural revitalization in the new era in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2018, 73, 637–650. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.L.; Liu, Y.X.; Zhao, M.Y. Establishing an economic insurance system under a multiple dynamic evolution mechanism after rural hollowing renovation. Resour. Sci. 2016, 38, 799–813. [Google Scholar]

- Song, W.; Chen, B.; Zhang, Y. Typical survey and analysis on influencing factors of village-hollowing of rural housing land in China. Geogr. Res. 2013, 32, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Opinions on Comprehensive Revitalization of the Rural and The Acceleration of Modernization in the Rural Agricultural Sector. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-02/21/content_5588098.htm (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Hediger, W. Reconciling “weak” and “strong” sustainability. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 1999, 26, 1120–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Han, L.; Yang, F.; Gao, L. The Evolution of Sustainable Development Theory: Types, Goals, and Research Prospects. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neumayer, E. Weak Versus Strong Sustainability: Exploring the Limits of Two Opposing Paradigms; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, W. Sustainability theory. In Berkshire Encyclopedia of Sustainability: The Spirit of Sustainability; Jenkins, W., Ed.; Berkshire: Great Barrington, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 380–384. [Google Scholar]

- Cabello, J.M.; Navarro-Jurado, E.; Thiel-Ellul, D.; Rodríguez-Díaz, B.; Ruiz, F. Assessing environmental sustainability by the double reference point methodology: The case of the provinces of Andalusia (Spain). Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2020, 28, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. The Ends and Means of Sustainability. J. Hum. Dev. Capab. 2013, 14, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wu, J. Sustainable landscape architecture: Implications of the Chinese philosophy of “unity of man with nature” and beyond. Landsc. Ecol. 2009, 24, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chio, J. Rendering rural modernity: Spectacle and power in a Chinese ethnic tourism village. Crit. Anthropol. 2017, 37, 418–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, S.; Peng, H. Tourism development, rights consciousness and the empowerment of Chinese historical village communities. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 772–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, R.L. Roles in Sociological Field Observations. Soc. Forces 1958, 36, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenbaum, T. The Handbook for Focus Group Research, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Using thematic analysis in counselling and psychotherapy research: A critical reflection. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2018, 18, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, N.; Han, J.; Mu, X.; Sun, Z.; Wang, H. Effects of improved materials on reclamation of soil properties and crop yield in hollow villages in China. J. Soils Sedim. 2019, 19, 2374–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.F.; Oya, C.; Ye, J. Bringing Agriculture Back in: The Central Place of Agrarian Change in Rural China Studies. J. Agrar. Chang. 2015, 15, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dates | Duration | Participants | Number of Participants | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focus Group 1 | On the first day of the fieldwork | 60.57 min | The company owner and 2 program managers | 3 |

| Focus Group 2 | On the second day of the fieldwork | 41.08 min | 1 employee-nonvillager, 2 employee-villagers and 3 nonemployee- villagers | 6 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, L.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Ou, Y.; Zhao, Z. Exploring the Relationship between Leisure and Sustainability in a Chinese Hollow Village. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810031

Zhou L, Liu L, Wang Y, Ou Y, Zhao Z. Exploring the Relationship between Leisure and Sustainability in a Chinese Hollow Village. Sustainability. 2021; 13(18):10031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810031

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Lijun, Lucen Liu, Yan Wang, Yuxian Ou, and Zijing Zhao. 2021. "Exploring the Relationship between Leisure and Sustainability in a Chinese Hollow Village" Sustainability 13, no. 18: 10031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810031

APA StyleZhou, L., Liu, L., Wang, Y., Ou, Y., & Zhao, Z. (2021). Exploring the Relationship between Leisure and Sustainability in a Chinese Hollow Village. Sustainability, 13(18), 10031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810031