Emotionally Sustainable Design Toolbox: A Card-Based Design Tool for Designing Products with an Extended Life Based on the User’s Emotional Needs

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. Card-Based Methods

2.2. Sustainable Product Design

2.3. Emotional Product Design

2.4. Emotionally Sustainable Product Design

2.4.1. Emotionally Durable Design (EDD)

2.4.2. Product Attachment

2.4.3. Other Theories

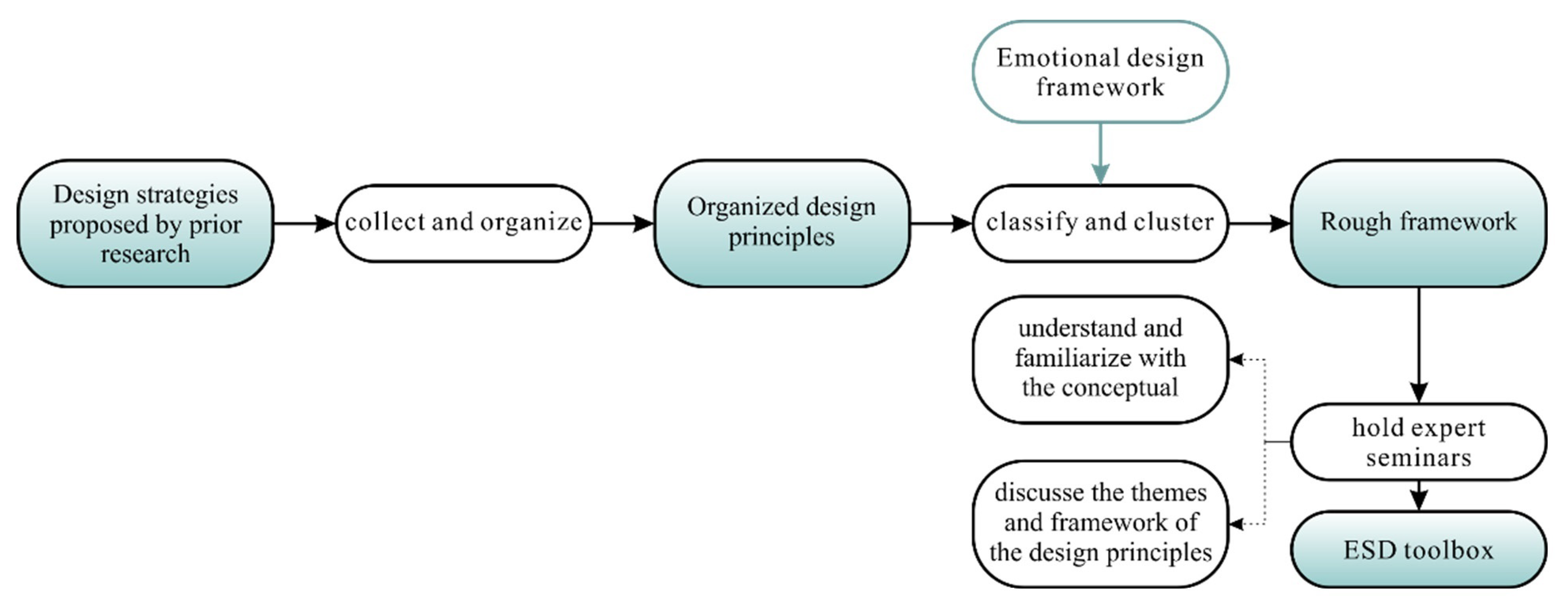

3. Method

3.1. Early Framework of Concepts

3.2. Improving the Toolbox

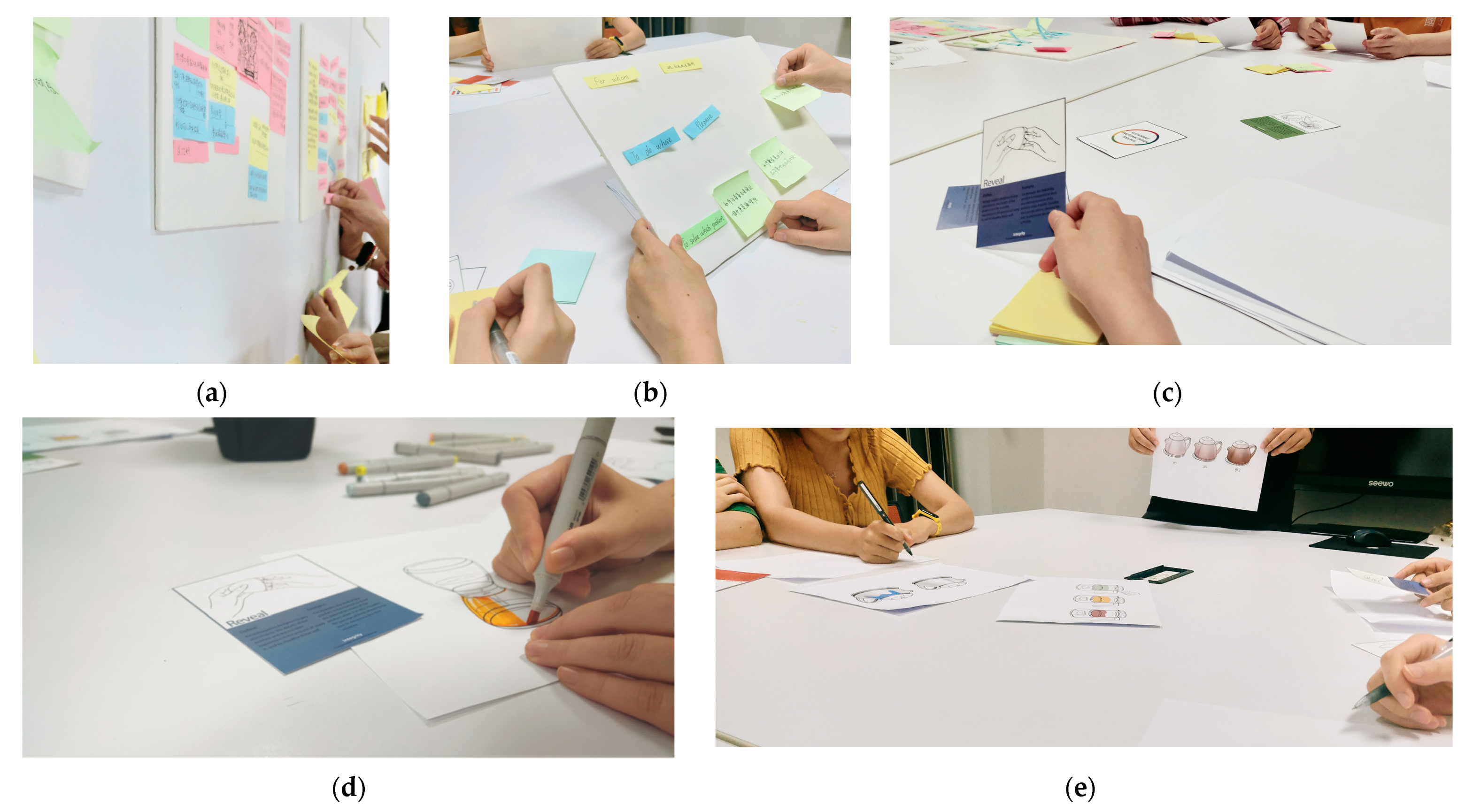

3.2.1. Process of the Seminar

- Do I understand the design principle well with the existing description?

- Does this principle help me design emotionally sustainable products?

- Which of the three levels of product experience does this design principle address?

- The product case proposed in response to this principle leads to a better product experience at which level or levels of the three levels?

3.2.2. Results of the Seminar

4. Introduction of the ESD Toolbox

4.1. Visceral Level

Pleasure

- Aesthetic design: The enjoyment and pleasure a product brings to users is the main driving force for the emotional sustainability of the product. Designing a product that evokes pleasure first requires it to evoke sensory and aesthetic pleasure. Among these, the visual and tactile experience of the product is considered to be the most effective in evoking user enjoyment. Therefore, it is a good design method to design products with a good user experience in terms of vision and touch.

- Surprise: Users will soon get used to the fresh and pleasant feeling conveyed by the product, which is called ‘hedonic adaptation’. Emotionally sustainable products need to evoke users’ pleasant experiences frequently—perhaps even different emotional experiences frequently—thereby trying to avoid users’ hedonic adaptation. Therefore, the task of the designer is to incorporate surprise into the product, to keep the product stimulating and engaging the user, and to create a sense of surprise and mystery for the user.

4.2. Behavioral Level

4.2.1. Integrity

- Usability: In his attachment framework, Norman emphasized the importance of usability in the relationship between consumers and products and suggested that the usability of products affects the enjoyment and pleasure of users using products. Therefore, there is no doubt that the usability of the product affects the experience of using it. Many factors affect the usability of a product, including product durability and quality. Durability and high quality are not only the physical premise for longer-lived products but also allow users to become emotionally dependent on the products over time and realize the emotional sustainability of the products.

- Visualization: Visualization requires designers to pay attention to something that may be ignored or unnoticed by the user while using the product, including the details of the product and the invisible experience during usage, and visualize these details and experience well. For example, the product shell could be designed to be transparent to show the internal structure of the product when it works or to visualize the passage of time so that users are aware of the progress of time. Good visualization can improve product integrity, realizing a smoother user experience and enhancing users’ sense of experiencing the product.

4.2.2. Adaptability

- Repair and maintenance: A product that is easy to maintain and repair is more reliable because the user can use it for a long time. In addition, products repaired by the users themselves are usually endowed with new emotions, giving the users a stronger sense of connection to the products. For easy maintenance, the product repair operation must be very simple, so that users can do it themselves. A good approach is to provide a modular design that simplifies maintenance to replacing modules.

- Aging well: The product changes and increased usage over time could form tangible physical features that improve usability. Aging well is different from product durability and high quality. The process by which the product changes over time can make the user feel as if the user is accompanying the product and helping the product evolve, thereby facilitating product attachment. For example, the tea deposits in a Zisha teapot are believed to be the result of wear over time and the user’s emotion.

- Flexible design: Form flexibility is concerned with providing the user with the possibility of alternative forms of the product without the need to add parts. The product can take several forms, with different use scenarios or different functions along with the growth of the user, or can also be completely user-determined, usually through modular component design.

4.3. Reflective Level

4.3.1. Develop Attachment

- Consciousness: If a product is perceived as autonomous, as having its own free will, it can significantly enhance the sense of connection between the product and the user. The products can be ‘weird’, often ‘moody’, and even require users to learn how to ‘communicate’ with them. This makes the interaction between the user and the product more interesting and enriches the user experience. When designing the way the product interacts with the user, the designer could imitate animal or human behavior to realize the autonomy of the product.

- Intimacy: If a user can develop a sense of intimacy with the product, there is no doubt that the user will become attached to the product, enhancing the emotional sustainability of the product. Building a close relationship with the user could be achieved by designing features that need to be used regularly. When a user needs to rely on the functions of the product to perform routine tasks, regular use of the product could be ensured. Frequent use of the product can build a high level of intimacy with the product.

- Ritual: A sense of ritual can lead to a great user experience, creating a ritual or habit that makes the product an important part of the user’s life. Designers can design special use methods according to the function of the product to form a sense of ritual or can directly design products that can help to create a sense of ritual atmosphere, such as enhancing lighting effect or a special scent.

- Aspiration: Product attachment and emotional persistence may occur when a user has positive expectations about using a product. This makes the user want to use the product by reflecting the user’s success or communicating the user’s social status, such as designing high-quality products or rewarding the user for using the product. Mutual altruism can support a relationship with the product.

4.3.2. Individual’s Value

- Evolvability: “Helping users grow” focuses on the long-term changes the product brings to the user, in the hope that users will learn some skills or create something to grow themselves over the long term. For example, long-term use of fitness equipment will help users to get a good figure, and long-term use of musical instruments will help users to acquire a skill. The product will witness the growth of the user. The process of self-growth is also the process of establishing a connection with the product.

- Self-expression: People use products to express themselves, and, therefore, products must adapt to the identity of the users. If a product is used to define and maintain a person’s personal identity, the product takes on special significance to the user. Self-expression focuses on the use of products to express a user’s personality or particular group identity, such as using environment-friendly bags to express the user’s identity as an environmentalist.

- Reflection: A product that triggers reflection can lead to a deeper emotional experience, which increases the chances that users will keep the product longer. What designers need to do is not ask users questions in a blunt way but make users stop and think about a profound question related to the meaning of their lives through clever metaphors in combination with the functions of the product so as to help users live a better life.

- Engagement: Users participate in the design and become designers. The more actively users participate in the design process, the more likely they are to have a stronger emotional attachment to the product they designed. This requires designers to stimulate the user’s desire to participate in the design through an unfinished product. Moreover, it is best to provide design references as far as possible to help users to create their own satisfactory design.

4.3.3. Memory

- Narrative: When a product carries more or stronger memories, users are more likely to keep the product for longer. In this case, the product can be used to recall the happy past and induce previous feelings of happiness. Designers can design nostalgic products, using the metaphor of products to achieve the recurrence of memory, or a special memory of the giver or recipient can also be attached to the product in the form of a gift.

- Participation: Participation in interaction refers to encouraging users to participate in the interaction with the product, thereby promoting the formation of special memories between the product and the user, so as to realize the emotional sustainability of the product. Through modularization, users can perform module changes to alter and interact with the product. This differs from users’ engagement in design in that participation in interaction provides not a semi-finished product but a complete product, taking advantage of the reinvention of the product to attract users to interact with it.

- Helping form memories: Products help users form memories of people, places, and events, while also making connections to important memories. Unlike shared memories, ‘product-assisted memories’ focus on helping users create and preserve memories, not just recall them. Products can be designed to help capture and reproduce the moment, or from the perspective of making memories, the designer can also design products that require group participation to help form memories of the people involved in the interaction or the interaction itself.

4.3.4. Positive Relations

- Belonging: Belonging is a product designed to support group affiliation, defining which group users belong to, and thus giving users a sense of belonging to a group. Instead of facilitating self-expression, designers design products to make users feel as if they are part of a group, rather than to reflect their identity. For example, products designed for a special social circle can make users feel that their social circle is significant and attracts attention.

- Making social connections: Social connection refers to helping users make social connections through the product. Encouraging users to engage in social activities and share experiences with others could help users build the desired personal connections with family, friends, or social groups. By designing products needed for social activities, designers could encourage users to use the products with others, naturally taking part in social activities. Product metaphors can also be used to remind users to connect with others or engage in social activities.

5. Design Practices Based on the ESD Toolbox

5.1. Design Thinking

5.1.1. Empathy

5.1.2. Define

5.1.3. Ideate

5.1.4. Prototype

5.1.5. Test Iteration

5.2. Feedback and Reflection

- Was the product ESD toolbox helpful to the design process?

- Did the toolbox help you take the emotional needs of your users more into account?

- Did you feel you had a better understanding of emotional sustainability?

- What design principles from the toolbox did you think could help you better design your products?

5.3. Presentation of the Design

6. Discussion

6.1. Application of the Toolbox

6.2. Research Limitations and Future Opportunities

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Béguin, P.; Duarte, F. Work and Sustainable Development. Work 2017, 57, 311–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Montabon, F.L.; Pagell, M.; Wu, Z. Making Sustainability Sustainable. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2016, 52, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchert, T.; Halstenberg, F.A.; Bonvoisin, J.; Lindow, K.; Stark, R. Target-driven selection and scheduling of methods for sustainable product development. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 161, 403–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceschin, F.; Gaziulusoy, I. Evolution of design for sustainability: From product design to design for system innovations and transitions. Des. Stud. 2016, 47, 118–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjaer, L.L.; Pigosso, D.C.A.; Niero, M.; Bech, N.M.; McAloone, T.C. Product/Service-Systems for a Circular Economy: The Route to Decoupling Economic Growth from Resource Consumption? J. Ind. Ecol. 2018, 23, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nie, Z.; Zurlo, F.; Camussi, E.; Annovazzi, C. Service Ecosystem Design for Improving the Service Sustainability: A Case of Career Counselling Services in the Italian Higher Education Institution. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haines-Gadd, M.; Chapman, J.; Lloyd, P.; Mason, J.; Aliakseyeu, D. Emotional Durability Design Nine—A Tool for Product Longevity. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ko, K.K.; Ward, S.J.; Ramirez, M.J. Understanding long term product attachment with a view to optimizing product lifetime. In Proceedings of the eddBE2011: 1st International Conference on Engineering, Designing and Developing the Built Environment for Sustainable Wellbeing, Brisbane, Australia, 27–29 April 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Thatcher, A. Affect in designing for sustainability in human factors and ergonomics. Int. J. Hum. Factors Ergon. 2012, 1, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juarez, G. The Role of Affective Design in Sustainability. In Advances in Interdisciplinary Practice in Industrial Design; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, J. Emotionally Durable Design; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nes, N.; Cramer, J. Influencing product lifetime through product design. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2005, 14, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, J. Design for (Emotional) Durability. Des. Issues 2009, 25, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Krieken, B.; Desmet, P.; Aliakseyeu, D.; Mason, J. A sneaky kettle: Emotionally durable design explored in practice. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Design and Emotion, London, UK, 11–14 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.; Antle, A.N.; Neustaedter, C. Tango cards. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Designing Interactive Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 21–25 June 2014; pp. 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, S.; Yilmaz, S.; Christian, J.L.; Seifert, C.; Gonzalez, R. Design Heuristics in Engineering Concept Generation. J. Eng. Educ. 2012, 101, 601–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jin, X.; Dong, H.; Evans, M. The Impacts of Design Heuristics on Concept Generation for a COVID-19 Brief. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schell, J. The Art of Game Design; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- IDEO. IDEO Method Cards: 51 Ways to Inspire Design; William Stout: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bloesch-Paidosh, A.; Shea, K.; Blösch-Paidosh, A. Design Heuristics for Additive Manufacturing Validated Through a User Study1. J. Mech. Des. 2019, 141, 041101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Warren, J. Card-based design tools: A review and analysis of 155 card decks for designers and designing. Des. Stud. 2019, 63, 125–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertwich, E.G. Life Cycle Approaches to Sustainable Consumption: A Critical Review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 4673–4684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Song, H.; Fan, C. Sustainable value creation from a capability perspective: How to achieve sustainable product design. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 312, 127552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glantschnig, W. Green design: An introduction to issues and challenges. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. Part A 1994, 17, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAloone, T.C.; Pigosso, D.C.A. From Ecodesign to Sustainable Product/Service-Systems: A Journey Through Research Contributions over Recent Decades. In Sustainable Manufacturing. Sustainable Production, Life Cycle Engineering and Management; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; De Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; Van Der Grinten, B. Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2016, 33, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zachrisson, J.L.D.; Boks, C. Exploring behavioural psychology to support design for sustainable behaviour research. J. Des. Res. 2012, 10, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tromp, N.; Hekkert, P.; Verbeek, P.P. Design for Socially Responsible Behavior: A Classification of Influence Based on Intended User Experience. Des. Issues 2011, 27, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamachi, M.; Nagamachi, M. Kansei Engineering: A new ergonomic consumer-oriented technology for product development. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 1995, 15, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, P.W. Designing Pleasurable Products: An Introduction to the New Human Factors; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, J.; Wright, P. Technology as experience. Interactions 2004, 11, 42–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.L.; Glasson, J.; Romeo, S.; Waters, R.; Chadwick, A. Entrepreneurial regions: Evidence from Oxfordshire and Cambridgeshire. Soc. Sci. Inf. 2013, 52, 653–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, D.A. Emotional Design: Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Page, T. Product attachment and replacement: Implications for sustainable design. Int. J. Sustain. Des. 2014, 2, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mugge, R.; Schoormans, J.P.L.; Schifferstein, H.N.J. Design Strategies to Postpone Consumers’ Product Replacement: The Value of a Strong Person-Product Relationship. Des. J. 2005, 8, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, D.; Thurgood, C.; van den Hoven, E. Designing Objects with Meaningful Associations. Int. J. Des. 2018, 12, 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Lobos, A.; Babbitt, C.W. Integrating Emotional Attachment and Sustainability in Electronic Product Design. Challenges 2013, 4, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaal, B. I is an Other: The Secret Life of Metaphor and How It Shapes the Way We See the World by James Geary. Metaphor. Symb. 2012, 27, 312–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugge, R. Emotional Bonding with Products; VDM Verlag Dr. Müller: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Grosse-Hering, B.; Mason, J.; Aliakseyeu, D.; Bakker, C.; Desmet, P. Slow design for meaningful interactions. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Paris, France, 27 April–2 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hekkert, P.; Cila, N. Handle with care! Why and how designers make use of product metaphors. Des. Stud. 2015, 40, 196–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, C.-H. The Association of Product Metaphors with Emotionally Durable Design. In Proceedings of the 2017 6th IIAI International Congress on Advanced Applied Informatics (IIAI-AAI), Hamamatsu, Japan, 9–13 July 2017; pp. 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casais, M.; Desmet, P.; Mugge, R. Objects with symbolic meaning: 16 directions to inspire design for well-being. J. Des. Res. 2018, 16, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sääksjärvi, M.; Hellén, K.; Desmet, P. The effects of the experience recommendation on short- and long-term happiness. Mark. Lett. 2015, 27, 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, C.F.; Fuadluke, A. The Slow Design principles: A new interrogative and reflexive tool for design research and practice. In Proceedings of the Changing the Change: Design, Visions, Proposals and Tools, Turin, Italy, 10–12 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, M.A.; Ponte, O.; Charnley, F. Taxonomy of design strategies for a circular design tool. In Proceedings of the PLATE 2017 Conference, Delft, The Netherlands, 8–10 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Agost, M.-J.; Vergara, M. Principles of Affective Design in Consumers’ Response to Sustainability Design Strategies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schifferstein, H.N.J.; Zwartkruis-Pelgrim, E.P.H. Consumer-Product Attachment: Measurement and Design Implications. Int. J. Des. 2008, 2, 325. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, H.; Bardzell, S.; Blevis, E.; Pierce, J.; Stolterman, E. How Deep Is Your Love: Deep Narratives of Ensoulment and Heirloom Status. Int. J. Des. 2013, 5, 59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Haug, A. Defining ‘Resilient Design’ in the Context of Consumer Products. Des. J. 2017, 21, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tianjiao, Z.; Tianfei, Z. Exploration of Product Design Emotion Based on Three-Level Theory of Emotional Design. In International Conference on Human Interaction and Emerging Technologies, Nice, France, 22–24 August 2019; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Razzouk, R.; Shute, V.J. What Is Design Thinking and Why Is It Important? Rev. Educ. Res. 2012, 82, 330–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Micheli, P.; Wilner, S.J.S.; Bhatti, S.; Mura, M.; Beverland, M.B. Doing Design Thinking: Conceptual Review, Synthesis, and Research Agenda. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2018, 36, 124–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, A.; Di Bucchianico, G.; Rossi, E. Strategies and arguments of ergonomic design for sustainability. Work 2012, 41, 3869–3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corsini, L.; Moultrie, J. Design for Social Sustainability: Using Digital Fabrication in the Humanitarian and Development Sector. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Theories | Strategies | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Sustainable product design | Reliability and robustness; repair and maintenance; upgradability; variability; product attachment | Nes, N.V.; Cramer J., 2005, [12] |

| Appearance; materials selection; product efficiency; user experience | Lobos, A., 2014, [37] | |

| Assure reliability; enhance durability; develop attachment; customize to wants and needs of each person | Beguerisse, M.M.; Ponte, O.; Charnley, F., 2017, [46] | |

| High durability; easy maintenance; refurbished; adaptable to new functions; flexible design; personalized | Agost, M.J.; Vergara, M., 2020, [47] | |

| Emotionally durable design (EDD) | Surface; users are enchanted by the product; attachment; detachment; consciousness; narrative | Chapman, J., 2009, [13] |

| Involvement; rewarding; animacy; adapt to the user’s identity; evoke memories | Van Krieken, B.; Desmet, P.; Aliakseyeu, D.; and Mason, J., 2012, [14] | |

| Imagination; integrity; materiality; evolvability; conversations; consciousness; identity; narratives; relationships | Haines-Gadd, M.; Chapman, J.; Lloyd, P.; Mason, J.; Aliakseyeu, D., 2018, [7] | |

| Product Attachment | Evoke enjoyment; memories | Schifferstein, H.N.J.; Zwartkruis-Pelgrim, E.P.H., 2008, [48] |

| Pleasure; self-expression; memories; group affiliation | Mugge, R. 2008 [39] | |

| Experiencing physical contact; individual’s value and ideology; memories to person, place and event; experiencing enjoyment with others | Ko, K.K.; Ward, S.J.; Ramirez, M.J., 2011, [8] | |

| Aficionado-appeal; rarity | Jung, H.; Bardzell, S.; Blevis, E.; Pierce, J.; Stolterman, E., 2013, [49] | |

| Pleasure; reliability; usability; adaptability; memories | Page, T. 2014 [34] | |

| Product Metaphor & Symbolic meaning of products & Slow design | Reveal; expand; evolve; participate; reflect; engage | Strauss, C.; Fuadluke, A., 2008, [45] |

| Reveal; expand; evolve; participate; reflect; engage; ritual | Grosse-Hering, B.; Mason, J.; Aliakseyeu, D.; Bakker, C.; Desmet, P., 2013, [40] | |

| Pleasure; intimacy; aspiration; self-image; memory; belonging | Ko, C.H., 2017, [42] | |

| Environmental mastery; autonomy; self-acceptance; personal growth; positive relations with others; purpose in life | Casais, M.; Mugge, R.; Desmet, P., 2018, [43] | |

| Incorporating significant memories and associations | Orth, D.; Thurgood, C.; van den Hoven, E., 2018, [36] | |

| Increasing sensory variety; aging well; maintenance quality; exclusivity; pre-purchase personalization; making social connections | Haug, A., 2018, [50] |

| 3 Levels | 7 Themes | 20 Principles | 20 Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visceral | Pleasure | Aesthetic design [7,8,13,34,35,42,43,50] |  |

| Surprise [7,14,43] |  | ||

| Behavioral | Integrity | Usability [12,34,46,47] |  |

| Visualization [40,45] |  | ||

| Adaptability | Repair and maintenance [12,34,46,50] |  | |

| Aging well [13,50] |  | ||

| Flexible design [12,47] |  | ||

| Reflective | Develop attachment | Consciousness [7,13,14] |  |

| Intimacy [7,12,13,42,49] |  | ||

| Ritual [40] |  | ||

| Aspiration [7,14,42] |  | ||

| Individual’s value | Evolvability [43] |  | |

| Reflection [7,14,40,42,45,47,49,50] |  | ||

| Self-expression [35,43] |  | ||

| Engagement [40,45] |  | ||

| Memory | Narrative [7,13,34,35,42] |  | |

| Participation [40,45] |  | ||

| Helping form memories [8,14,36] |  | ||

| Positive relations | Belonging [35,42] |  | |

| Making social connections [8,50] |  |

| Aesthetic design | Surprise | Usability | Visualization |

|  |  |  |

| This design is modeled by simulating an object to bring aesthetic enjoyment. | The different temperatures will lead to different and patterns each time the tea is made. | The teapot is made of a metal sheet. | The rotation scale can be used to set the tea-brewing time. |

| Repair and maintenance | Aging well | Flexible design | Consciousness |

|  |  |  |

| The design turns the teapot maintenance into a simple replacement action. | Each time the tea is made, it leaves a mark on the teapot, which can form a pattern similar to growth rings. | The lid of the teapot can be split to make a teacup. | The smart teapot can send regular invitations to friends. |

| Intimacy | Ritual | Aspiration | Evolvability |

|  |  |  |

| The traveling teapot is designed to be carried around by the user. | Small ritual items are provided to add a ritual sense to the activity of drinking tea. | According to the different effects of the tea, the user will be reminded about the health effects. | It can help users acquire tea-related knowledge. |

| Self-expression | Reflection | Engagement | Narrative |

|  |  |  |

| Zisha teapots symbolize identity and culture, and each teapot will be engraved with a unique logo. | The outer surface of the teapot will crack when the water overflows, prompting the users to reflect that ‘the moon waxes only to wane, and water surges only to overflow’. | For this design, users can weave their own tea handles to participate in the design. | The teapot can record or take pictures, and its electronic screen can display the last time a friend interacted with the user. |

| Participation | Help form memories | Belonging | Making social connections |

|  |  |  |

| The teacups are designed in the shape of petals and can be used to form different patterns by altering their positions. | A lovers’ teapot allows users to see how their partner is drinking tea by changing the texture on their teapots. | A healthy teapot is specially designed for people who value health preservation. It has the functions of stewing and boiling. | Drawing from an ancient drinking game, the design allows the user to interact with others while making tea. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, J.; Jin, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, M.; Dong, X. Emotionally Sustainable Design Toolbox: A Card-Based Design Tool for Designing Products with an Extended Life Based on the User’s Emotional Needs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810152

Wu J, Jin C, Zhang L, Zhang L, Li M, Dong X. Emotionally Sustainable Design Toolbox: A Card-Based Design Tool for Designing Products with an Extended Life Based on the User’s Emotional Needs. Sustainability. 2021; 13(18):10152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810152

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Jianfeng, Chuchu Jin, Lekai Zhang, Li Zhang, Ming Li, and Xuan Dong. 2021. "Emotionally Sustainable Design Toolbox: A Card-Based Design Tool for Designing Products with an Extended Life Based on the User’s Emotional Needs" Sustainability 13, no. 18: 10152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810152

APA StyleWu, J., Jin, C., Zhang, L., Zhang, L., Li, M., & Dong, X. (2021). Emotionally Sustainable Design Toolbox: A Card-Based Design Tool for Designing Products with an Extended Life Based on the User’s Emotional Needs. Sustainability, 13(18), 10152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810152