1. Introduction

Democratic innovations, or processes enabling citizens to influence decision-making on important social and political issues, are often championed as providing a solution to the crisis of representation affecting established democracies [

1]. European democracies are making more consistent use of direct democratic processes, such as referendums and initiatives, that are popular among majorities of citizens [

2]. However, scholars and policymakers have increasingly turned their attention to deliberative processes emphasizing focused discussions among ordinary citizens as a crucial component of decision-making. An example of such processes is the deliberative “mini-public” (DMP), or a body of citizens selected by lot to reflect the characteristics of the general population, which gathers to deliberate and decide on specific policy issues [

1].

Recent studies have shown that DMPs are being used more frequently across established democracies to inform policymaking on an expanding portfolio of topics [

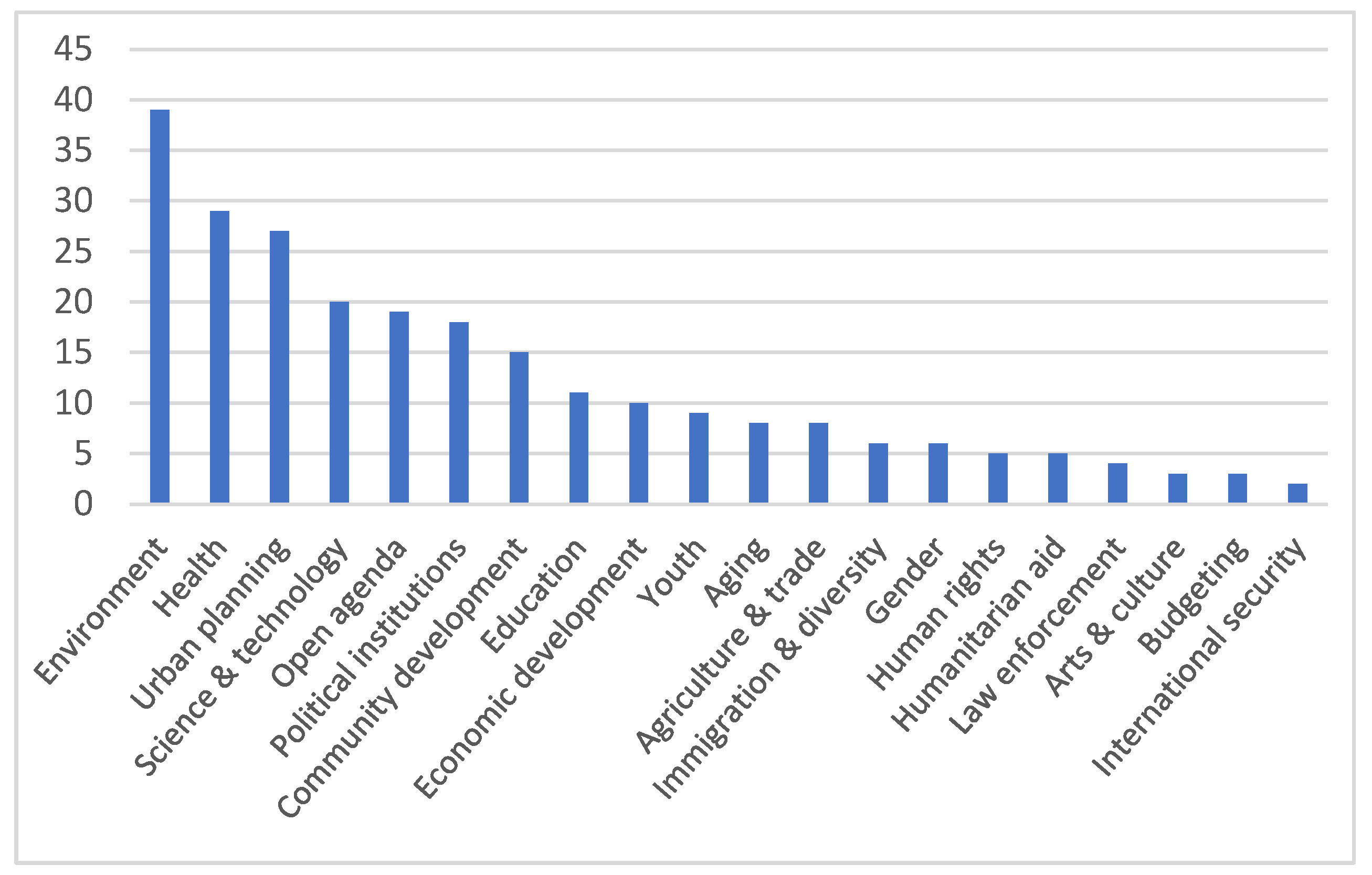

3]. As shown in

Figure 1, the environment was the most common topic for DMPs held in European democracies between 2000 and 2020, closely followed by other topics related to sustainability, such as science and technology and urban planning [

4]. Although DMPs are increasingly popular, they remain a novel approach to policymaking in most democracies. Therefore, the potential of these innovations for addressing sustainability issues depends on the extent to which ordinary citizens perceive them as legitimate channels for policymaking and are willing to get involved.

To assess the potential of democratic innovations for policymaking, scholars have sought to gauge public support for the use DMPs. Studies from the US [

5,

6], Belgium [

7,

8], and the UK [

9] have shown that DMPs are relatively popular, even if less so than referendums. Most studies have focused on separating the advocates of democratic innovations from the critics and determining whether the advocates are politically “engaged” or politically “enraged” [

10,

11,

12]. However, there may be several groups of citizens with different levels of support for democratic innovations and distinct socio-demographic and attitudinal characteristics. Furthermore, most studies have ignored a potential gap between support and willingness to participate, assuming that support for democratic innovations translates to participation [

13]. However, some citizens may intend to participate despite rejecting a more institutionalized role for DMPs, whereas others may be less inclined to participate despite supporting the initiative to get citizens involved.

In an online vignette study conducted in the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, and the UK, we presented 1559 respondents with varying descriptions of a local DMP. Attitudes towards deliberative democratic innovations were measured by asking respondents to rate their support for the DMPs described as well as their willingness to participate if invited. Using latent profile analysis, we identified several groups or “classes” of citizens with distinct patterns of support and willingness to participate. Whereas critics neither support nor would participate in a local DMP, engaged deliberative democrats are both supportive and willing to participate. In addition, we also identified “skeptical” citizens who reject the use of DMPs despite intending to participate and “indifferent” citizens who show neither positive nor negative predispositions towards DMPs. Building on these findings, we compared the socio-demographics and political attitudes of the four groups.

On one hand, the viability of DMPs for addressing sustainability issues rests on the ability of policymakers and practitioners to convince not only the critics but also the skeptics and those who are indifferent. On the other hand, citizens who prioritize the environment over any other issue of concern are most likely to be identified as engaged deliberative democrats.

2. Literature Review: Who Are the Deliberative Democrats?

For many years, scholars have taken an interest in citizens demanding a greater role in shaping public policy, potentially undermining the authority of elected officials. More specifically, they have tried to understand who these citizens are and how they differ from the rest of the public. According to

cognitive mobilization theory, citizens demand more opportunities to decide on important matters affecting their lives since they are interested and engaged in politics. According to

political disaffection theory, citizens seek alternative processes due to the fact that they are enraged with politics as usual, which they perceive as distant and unresponsive [

10,

11,

12]. These theories have encouraged scholars to search for one of two mutually exclusive profiles, instead of considering a typology. As a result, empirical research has often produced contradictory findings [

14]. Some studies found that participatory processes are preferred by citizens who are politically engaged and confident their participation will make a difference [

10,

12]. Others found that participatory processes are preferred by those who are lower educated, less confident in their ability to influence politics, and distrusting of political actors and institutions [

7,

8,

11,

15].

One explanation for this mixed bag of results is that these theories work hand-in-hand, implying that deliberative democrats are both engaged and enraged. Gamson claimed that “a high sense of political efficacy and low political trust is the optimum combination for mobilization” [

16] (p. 48). This claim is reflected in the concept of

critical citizens or individuals who support the institutions of democracy but have acquired sufficient skills and knowledge to challenge the decisions of political elites [

17]. Providing evidence for this, a study in Belgium found that support for DMPs that would replace local councils is strongest among citizens who are both confident in their ability to influence politics and dissatisfied with political parties and elected officials [

7].

Another explanation is that there are several types of deliberative democrats; some are either engaged or enraged and others are simultaneously enraged and engaged. Webb is the only scholar who provided evidence for this idea. Using survey data from the UK, he demonstrated that there are two kinds of democrats, both of whom are dissatisfied with politics [

9]. The dissatisfied democrats are more politically interested and efficacious, therefore preferring intensive modes of engagement such as deliberation. By contrast, the stealth democrats are less politically interested and efficacious, therefore preferring easy modes of engagement such as referendums.

Webb’s research opens a new avenue for studying attitudes towards democratic innovations by suggesting that we should pay more attention to the difference between wanting more say and wanting to get involved. There may be democrats who would not participate, despite being favorable towards DMPs. Vice versa, there may be democrats who would participate despite being unfavorable towards DMPs, which has not been articulated in the literature.

Most studies investigated support for the introduction of specific democratic innovations or for the broader notion of citizens playing a role in decision-making processes. Only a few studies investigated citizens’ past participation or willingness to participate in democratic innovations [

5,

9,

18]. Support and participation are both important as they tell us different things: whereas support is an indication of the perceived legitimacy of participatory processes, participation is an indication of their potential for inclusiveness.

Research from the US demonstrated that Americans’ increased support for direct citizen participation did not imply increased willingness to get involved in politics, suggesting a potential support-participation gap [

18]. By contrast, studies in Finland [

13] and Germany [

19] demonstrated that support and participation are linked. However, these studies examined correlations between citizens’ broader decision-making preferences and their participation in a range of political behaviors, e.g., voting, protesting, demonstrating and boycotting, instead of comparing support for and participation in the same decision-making process. Furthermore, a positive correlation between support and participation does not rule out the possibility that a support-participation gap exists for

some citizens.

Support may not translate into participation since the latter requires greater skills and resources than the former [

19]. Several characteristics are known drivers of political participation, namely income, education, and political interest [

20], and hence those who make the step from support to participation are likely to possess more of these traits. Another explanation is that in theory participatory processes are a good idea, but in practice politicians do not listen to what citizens have to say, and therefore participation is perceived as a waste of time. Vice versa, participation in democratic innovations does not guarantee support. This may be due to the fact that some citizens are relatively satisfied with the performance of political elites, whom they perceive as better equipped to take decisions than the masses. However, should the opportunity arise, these citizens would participate as they would not want decisions to be taken by less competent citizens.

Building on the distinction between support and participation, we expect to identify four groups of individuals with differing patterns of support and willingness to participate in a DMP (see

Table 1).

Disengaged deliberative democrats support greater use of DMPs, but are less likely to participate in one if invited (

H1a).

Skeptical deliberative democrats reject a more institutionalized role for DMPs, but would not miss out on an opportunity to take decisions (

H1b).

Engaged deliberative democrats are both enthusiastic about DMPs and eager to participate in one (

H1c). Finally,

critics neither support nor would participate in a DMP (

H1d). In the following section, we extend previous theories on the demand for participatory processes, developing hypotheses on the distinct socio-demographic and attitudinal profiles of these four groups.

3. Socio-Demographic and Attitudinal Characteristics of the Four Groups

Disengaged deliberative democrats are inspired by the literature on stealth democracy [

18]. These citizens are in favor of shifting decision-making opportunities away from politicians, whom they perceive as unresponsive and corrupted. Despite supporting democratic innovations, disengaged democrats are unlikely to participate since they lack the resources and motivation to engage in politics, which they perceive as complicated and distant. Furthermore, they feel their participation would not make a difference since representative institutions are not responsive, especially to people like themselves. Therefore, we expect that disengaged deliberative democrats are less skilled and resourceful and more critical of political elites and institutions than other attitude groups (

H2). Skills and resources refer to both

objective goods such education and income and

subjective goods such as interest in politics and feelings of internal political efficacy [

7].

Skeptical deliberative democrats are similar to those Bedock describes as individuals with an “entrustment” conception of politics [

21]. Despite being interested in politics, skeptics do not support a sustained role for citizens in policymaking since politics is not for everyone. Hence, citizens should not be involved beyond selecting more competent leaders with superior qualities. These individuals are less negative about politics as they come from privileged backgrounds. Higher status groups are generally better represented and therefore less likely to favor alternative political processes [

22]. For example, a study from Canada demonstrated that better informed citizens are more skeptical of referendums since they are satisfied with government [

23]. Although they do not support a more prominent role for citizens in policymaking, skeptics would not miss out on an opportunity to decide since they are still interested in politics and want to avoid decisions taken by those less competent than themselves. Therefore, we expect that skeptical deliberative democrats are more skilled and resourceful and more satisfied with political elites and institutions, but less confident in the abilities of ordinary citizens to understand politics than other attitude groups (

H3).

Engaged deliberative democrats come closest to those Norris describes as “critical citizens” [

17]. Similarly to the disengaged, they are in favor of shifting decision-making away from underperforming politicians to ordinary citizens. However, unlike the disengaged, they are eager to participate in decision-making since they are more interested in politics and feel their participation will make a difference. Contrary to skeptics, engaged democrats are strongly opposed to the professionalization of politics, which they believe should be carried out by ordinary citizens temporarily engaged in collective initiatives for the common good [

21]. Therefore, we expect that engaged deliberative democrats are more skilled and resourceful, more critical of political elites and institutions, and more confident in the abilities of ordinary citizens to understand politics than other attitude groups (

H4).

Finally, the fourth group expected are the

critics of deliberative decision-making. In a recent study from Belgium, Pilet and colleagues identified a significant subgroup of citizens who remain positive about elected politicians and are very critical of including citizens in policy-making [

24]. Similarly to the skeptics, critics might be more trusting of political elites and institutions and less confident in the abilities of ordinary citizens to understand politics. Unlike skeptical and engaged democrats, critics would be less interested in politics, less skilled and resourceful and less confident in their own capacity to influence politics (

H5).

4. Data

The data analyzed is from an online vignette study conducted by the POLPART project in the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland and the UK during summer 2017. Respondents were recruited from online panels by a market research company employing the same recruitment strategy in all countries. The samples range between 364 (UK) and 418 (Switzerland) participants per country.

The four countries have sufficiently diverse political systems to investigate whether the attitudinal groups described in the hypotheses exist across differing institutional contexts. Whereas Germany and Switzerland are federal democracies, the UK and the Netherlands are unitary states. Unlike the other three countries, the UK is a majoritarian democracy with lower levels of territorial and institutional decentralization [

25]. Switzerland stands out as a semi-direct democracy where citizens can participate in political decision-making through referendums and initiatives at different levels of government.

Since the 1990s, the use of deliberative democratic innovations has been expanding in the Netherlands, Germany and the UK. However, these initiatives are often implemented ad hoc, loosely connected to policymaking and specific to a few cities or regions [

25,

26,

27]. Municipalities in the Netherlands have experimented with citizens’ juries, participatory budgeting, and citizens’ summits. Mini-publics composed of randomly-selected citizens referred to as “G1000” were implemented to reinvigorate representative democracy in at least a dozen municipalities [

27]. In Germany, a similar initiative known as “Planning Cells”, of which more than 50 cases have been recorded, bring together randomly-selected citizens to influence decision-making on urban development [

28]. In the UK, participatory budgeting has been employed by at least 100 local authorities and hundreds of citizens’ juries have encouraged deliberation on topics related to science and technology, the environment and healthcare [

25]. In Switzerland, deliberative democratic innovations organized in support of direct democratic votes, such as the citizens’ initiative review, are slowly emerging [

29].

Online surveys are increasingly common in research on citizens’ political attitudes and behaviors [

30]. However, as a result of self-selection into online panels, respondents in these surveys may differ on certain characteristics from the general population. To ensure an optimally representative sample, we constructed weights matching the distributions on age, sex, and education among the general population of each country. These weights were modelled on post-stratified samples from the 2016 European Social Survey, excluding persons older than 65 years who are underrepresented in online surveys. Research from the US has shown that with appropriate weighting, samples recruited through online panels are sufficiently representative of the general population to be used as alternatives to probability samples, such as those constituted through random digit dialing [

31].

5. Variable Measures

Citizens’ attitudes towards deliberative innovations were measured by presenting respondents with two randomly generated “vignettes” or descriptions of a local DMP. The vignettes provide more information about the design of DMPs than standard survey items, which is crucial for capturing attitudes towards relatively complex and unusual political processes [

32]. We chose to focus on local politics, where the issues and consequences are more immediate and concrete [

25].

Besides the key criteria of (a) citizen participation, (b) random selection, and (c) deliberation (which are emphasized in all vignettes), DMPs come in a variety of shapes and sizes. To better reflect the diversity of institutional designs, the initiators, size, composition, number of topics, and outcome of the DMP were randomly varied across the vignettes presented to respondents. The full vignette text with all potential attribute levels is provided below. Full randomization implies that vignette characteristics are independent from respondent characteristics (e.g., all respondents had an equal chance of receiving an advisory or binding DMP) and therefore do not need to be included as controls [

33].

Imagine that residents in your town or city were given the opportunity to influence political decisions at the local level by participating in a citizens’ meeting. The meeting will be organized by [local politicians/an independent organization] and composed of [25/100/500] randomly selected citizens from different socio-economic backgrounds [however, efforts will be made to invite citizens from lower socio-economic backgrounds whose views are not often heard/blank]. Together, these citizens will discuss [one/several] important political questions and collectively take decisions. The decisions taken are [advisory, which means the local government can choose whether to implement them/binding, which means the local government must implement them].

Following each vignette, respondents answered two questions on

support and

willingness to participate in the DMP. These measures represent the observed attitudinal outcomes determining membership to the different groups described in the hypotheses. As a measure of support, respondents indicated whether the DMP described was a bad or good way of taking decisions in their town or city on a scale ranging from “very bad” (0) to “very good” (10). Support for local DMPs was far from overwhelming, with an average score of 5.43 out of 10. As a measure of willingness to participate, respondents indicated how likely they would be to participate in the DMP if invited on a scale ranging from “very unlikely” (0) to “very likely” (10). While prospective (as opposed to past) participation might be considered a limitation, real opportunities to participate in DMPs are few and far between, even at the local level [

32]. Overall willingness to participate was slightly higher than support, with an average score of 5.89 out of 10.

Figure 2 demonstrates that despite institutional differences, respondents’ overall scores on support and willingness to participate are similarly structured across all countries, with the exception that support is lower in the Netherlands and Switzerland and willingness to participate is higher in Germany.

Several independent variables were included to test hypotheses (H2–H5) comparing the socio-demographics and political attitudes of the four groups.

Education and

income measure objective or “hard” skills and resources. Education is derived from the International Standard Classification of Education and ranges from less than lower secondary education (0) to higher tertiary education (6). Although deliberative skills can be learned through participation in a DMP, previous research has shown that higher educated individuals exhibit more deliberative qualities (e.g., justification rationality, common good orientation, constructive politics) than lower educated individuals [

34]. Therefore, educational attainment is a suitable proxy for certain deliberative skills. As a measure of income, respondents rated their feelings about their household income nowadays on a scale ranging from “very difficult on present income” (0) to “living comfortably on present income” (3).

Political interest and internal political efficacy measure subjective or “soft” skills and resources. Respondents indicated how interested they are in politics on a scale ranging from “not at all interested” (0) to “very interested” (3). As a measure of internal political efficacy, respondents rated their agreement with the statement “I am confident in my own ability to participate in politics” on a scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (0) to “strongly agree” (4).

The relationship between political disaffection and political process preferences may depend on how attitudes towards politics are measured [

14]. Therefore, both

anti-elitism and

trust in representative institutions were included to respectively account for “specific” and “diffuse” political support. Anti-elitism is a scale averaging each respondent’s scores on four statements about the qualities of elected officials, ranging from “strongly disagree” (0) to “strongly agree” (4) (see

Appendix A for item wording). These statements formed a reliable scale in each country, with alphas above 0.80. Trust in representative institutions is a scale averaging each respondent’s scores on trust in parliament, political parties and politicians ranging from “no trust at all” (0) to “complete trust” (4). These items formed a reliable scale in each country, with alphas above 0.85.

As a measure of confidence in ordinary citizens respondents rated their agreement with the statement that “most citizens have enough sense to tell whether the government is doing a good job” on a scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (0) to “strongly agree” (4).

Age and

sex (female = 1) were included as control variables. Descriptives of all variables are provided in

Table 2.

7. Results

Based on the four attitude groups described in the hypotheses, respondents’ support and willingness to participate in a local DMP were used to fit a four-cluster latent class model. The goodness of fit statistics for models with one up to six clusters of respondents are provided separately by country in

Appendix B,

Table A1. A comparison of the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) demonstrates that a four-cluster model provides the most optimal solution in all countries except the UK, where the BIC is only slightly improved by fitting a model with four classes. Selecting a model with a greater number of classes based on a slightly smaller BIC may undermine the interpretability of groups [

37]. Indeed, we found that a four-cluster model on data from the UK produced a group of respondents who differ very little from the engaged democrats. Therefore, we pursue our analyses with three classes in the UK as opposed to four classes in the remaining countries.

Table 3 presents the marginal latent class probabilities and marginal predicted means of the indicators within each latent class, separately by country. The marginal latent class probabilities represent the expected proportion of the sample in each class. The marginal predicted means represent the strength of support for local DMPs and willingness to participate in one as distinguishing who would be a member of each class. In all models the standard errors were clustered at the respondent level to account for the two vignettes per respondent and the samples were weighted to match the distributions on age, sex, and education in the general population.

Between 11 and 18% of the sample was classified as members of the first class, with the smallest proportion in the Netherlands and the greatest proportion in Switzerland. The first class is distinguishable from the others by its low levels of support for local DMPs coupled with an even lower likelihood of participating in one. Therefore, this class corresponds most with the “critics” of deliberative innovations described in H1d.

Between 41 and 50% of the sample was classified as members of the second class, with the smallest proportion in Germany and the greatest proportion in the Netherlands. The second class is distinguishable from the others by its average levels of support for local DMPs coupled with an average likelihood of participating in one. This class does not correspond with any of the groups described in the hypotheses, but given that they are neither enthusiastic nor pessimistic about local DMPs we hereafter refer to them as “indifferent”. This label has been used in previous research on other political attitudes to describe individuals lacking both a positive or negative affect [

38]. It is worth noting that this is the largest group in all countries except Germany.

Between 5 and 12% of the sample was classified as members of the third class, with the smallest proportion in Germany and the greatest proportion in the Netherlands. The third class is distinguishable from the others by its very low levels of support for local DMPs coupled with a very high likelihood of participating in one. Therefore, this class corresponds most with the “skeptics” of deliberative innovations described in H1b. Skeptical democrats were not identified in the UK, where a four-cluster model generated a third class that differed very little from the engaged democrats.

Finally, between 28 and 42% of the sample was classified as members of the fourth class, with the smallest proportion in the Netherlands and the greatest proportion in Germany. The fourth class is distinguishable from the others by its very high levels of support for local DMPs coupled with a very high likelihood of participating in one. Therefore, this class corresponds most with the “engaged” deliberative democrats described in H1c.

In all countries we find groups of respondents who are indifferent, engaged and critical. Indifferent democrats are not very enthusiastic about local DMPs and only somewhat willing to participate in one. Engaged democrats are both enthusiastic and eager to participate in such forums. Critics not only reject the use of local DMPs but are also the least likely to participate. In the Netherlands, Germany, and Switzerland we find skeptical democrats who reject the use of local DMPs (except in the Netherlands) but would not miss out on an opportunity to join one. Contrary to expectations (H2) we did not uncover a group of disengaged democrats, who support the use of local DMPs but would not participate. However, it may be that the expected characteristics of disengaged democrats are shared by those identified as indifferent or critical.

The similarity of classes in the Netherlands, Germany, and Switzerland is a strong argument for combining the data from these countries. Therefore, we pursue our analysis of the socio-demographic and attitudinal predictors of class membership for the three continental European countries versus the UK separately.

Figure 3 provides a visual representation of the characteristic features of each class in the pooled data versus the UK.

We now turn to the hypotheses comparing the socio-demographic and attitudinal characteristics of the different classes (H2–H5).

Figure 4 plots the average marginal effects (AMEs) or average change in the probability of class membership for a one unit increase in the predictors, separately for the UK and the three remaining countries. The AMEs are derived from a multinomial logistic regression with class membership as a categorical dependent variable and those who are indifferent as the reference group. To facilitate comparison of the results with the hypotheses, the AMEs are reported by class as opposed to in the order of predictors.

Starting with the pooled data from the Netherlands, Germany, and Switzerland, a one unit increase in political interest, political efficacy or confidence in the abilities of ordinary citizens decreases the probability of being a critic of local DMPs. All other predictors have very little effect on belonging to this class. These findings confirm expectations that critics are less engaged in politics and question the abilities of fellow citizens to understand politics, but not that they are more trusting of political elites and institutions (H5). Results from the UK suggest that the critics are also higher educated, wealthier, and less trusting of representative institutions (contrary to expectations). However, these differences may depend on the comparison group, as argued later on.

An increase in education, political interest, political efficacy, anti-elitism, or trust in representative institutions decreases the probability of being indifferent towards deliberative decision-making. Although we failed to develop expectations for this group, the findings demonstrate that individuals who are indifferent towards the use of DMPs in local policymaking are less politically engaged and less critical towards politicians, but are not as trusting of the broader institutions of representative democracy. In fact, this group appears to score the lowest on interest, efficacy, anti-elitism, and trust in institutions. In the UK, those who are indifferent are also less engaged and more forgiving of political elites. Contrary to their European counterparts, they appear to be more trusting of institutions and less confident in fellow citizens, but these differences disappear in the following analysis where they are not the reference group.

An increase in education, political interest or political efficacy increases the probability of being skeptical of deliberative decision-making. By contrast, an increase in anti-elitism and confidence in fellow citizens decreases the probability of being skeptical. These findings confirm expectations that skeptics, who would participate but do not support local DMPs, are more skilled and resourceful, more confident in political elites and less confident in ordinary citizens (H3).

Whereas an increase in education decreases the probability of being an engaged deliberative democrat, an increase in political interest, political efficacy, anti-elitism, trust in institutions, or confidence in citizens increases the probability of belonging to this class. These findings confirm expectations that engaged democrats, who are both optimistic and willing to participate in a local DMP, possess more subjective skills and resources, are more critical of political elites and have faith in the political competencies of fellow citizens (H4). Contrary to expectations, engaged democrats are not more critical towards representative institutions. This suggests that the strongest engagement with deliberative innovations comes from individuals who have faith in the system but express concerns about its leaders. Engaged democrats in the UK share similar characteristics with their continental counterparts.

While the AMEs show how socio-demographics and political attitudes influence class membership, they do not test differences between classes. Furthermore, the AMEs are based on a MNL regression whereby each class is compared only to the reference group (indifferent citizens). Therefore, we also present the results of separate linear regressions estimating the probability of membership to each class. The results from the three continental European countries and the UK are presented in

Table 4 and

Table 5, respectively.

Table 4, Model 1, shows the effects of our predictors on the probability of being a

critic of deliberative innovations in the Netherlands, Germany, and Switzerland. A one unit increase in political interest or confidence in ordinary citizens is associated with a decrease in the probability of being labelled a critic. This confirms expectations that critics of DMPs are not as engaged in politics and do not think fellow citizens are capable of being engaged either (H5). However, there is no evidence that critics come from lower socio-economic strata or that they are (dis)satisfied with political elites and institutions. These findings are further substantiated in the UK (presented in

Table 5, Model 1), with the exception that critics appear to be wealthier, despite being less politically interested and efficacious than others.

Table 4, Model 2 shows the effects of our predictors on the probability of being

indifferent towards deliberative innovations in the Netherlands, Germany and Switzerland. A one unit increase in education, political interest or confidence in one’s ability to influence politics is associated with a decrease in the probability of being indifferent. This demonstrates that those who are indifferent towards the use of local DMPs have less of the objective and subjective skills and resources needed to participate in politics. Furthermore, anti-elitism and trust in representative institutions are both negatively related to the probability of being indifferent. Therefore, despite being the most critical of representative organs, this group is not critical of politicians per se. Indifferent democrats in the UK share similar features, with the exception that they are not lower educated than others (see

Table 5, Model 2).

Table 4, Model 3 shows the effects of our predictors on the probability of being

skeptical of deliberative innovations in the Netherlands, Germany, and Switzerland. A one unit increase in education, political interest or confidence in one’s ability to influence politics is associated with an increase in the probability of being skeptical. This confirms expectations that skeptics have more of the objective and subjective skills and resources needed to participate in politics (H3). Furthermore, anti-elitism and confidence in citizens are both negatively related to the probability of being a skeptic. This is in line with expectations that those who are skeptical of local DMPs are trusting of politicians whom they perceive as more competent than ordinary citizens.

Finally,

Table 4, Model 4 shows the effects of our predictors on the probability of being an

engaged deliberative democrat in the Netherlands, Germany, and Switzerland. Whereas political interest and confidence in one’s ability to influence politics increase the probability of being engaged, education decreases the probability of membership to this group. These findings confirm that engaged democrats are cognitively mobilized, but (contrary to expectations) do not possess more of the “hard skills” needed to participate in politics (H4). Anti-elitism and confidence in citizens are both positively related to the probability of being engaged. This is in line with expectations that engaged democrats are more critical of politicians and have more faith in the abilities of ordinary citizens to understand politics. Contrary to expectations, trust in representative institutions is associated with an increase in membership to this group. Hence engaged democrats trust the system more generally but not its the leaders, whose functions they might like to see performed by ordinary citizens. Engaged deliberative democrats in the UK share similar features, with the exception that they are not lower educated or more confident in ordinary citizens than others (see

Table 5, Model 3).

9. Discussion

Whereas previous research has focused on separating the enthusiasts of direct citizen participation from the critics, our results demonstrate that citizens’ attitudes are more varied, especially when taking into consideration both support and willingness to participate. In addition to the enthusiasts and critics of DMPs, we also identified indifferent and skeptical citizens who have not received particular attention in the literature (see

Table 6).

In the four western European democracies examined, the truly engaged deliberative democrats, in the sense that their support for local DMPs is reinforced by intentions to participate, correspond to roughly one-third of citizens. The socio-demographic and attitudinal profile of engaged democrats emphasize the shortcomings of theories that characterize those with inclinations towards direct citizen participation as either “engaged” or “enraged”. In line with some previous research [

7], we find that these individuals are

both confident in their abilities to influence politics and critical of elected officials.

However, our results offer further insights into the characteristics of engaged deliberative democrats. Firstly, despite being politically interested and efficacious, they do not necessarily possess more of the “hard” skills needed to participate, namely education. Instead, we find that among those who intend to participate, the higher educated are more skeptical of local DMPs. Second, while engaged democrats are more critical of elected officials, they are also more trusting of representative institutions, suggesting that they perceive DMPs as a corrective for unresponsive and corrupted elites rather than an alternative way of doing politics. Finally, engaged democrats are more concerned about the environment than any other issue, suggesting that DMPs would attract individuals who care about sustainability.

In the four Western European democracies examined, only a small proportion of citizens outright reject local DMPs. The socio-demographic and attitudinal profile of the critics suggests that rejection of DMPs has mostly to do with a lack of interest in politics and a feeling that citizens cannot influence policymaking, potentially due to their limited knowledge and experience. There is little evidence that critics come from a particular socio-economic group or that they are driven by higher levels of trust in politics, with the exception that critics in the UK appear more satisfied with their household incomes.

Our expectations were influenced by prior research assuming polarization between the critics and enthusiasts of direct citizen participation. Hence, we did not develop expectations for a group of citizens that expresses indifference, or the absence of a positive or negative affect, towards local DMPs. However, the results demonstrate that the majority of citizens in all countries examined except Germany (where they still account for 41%) actually sit on the fence. This finding is echoed by another contribution to this special issue, demonstrating that at least one-third of Germans are indifferent towards the use of randomly-selected citizen assemblies for local policymaking [

26]. Psychological research tells us that citizens generally have difficulties forming clear attitudes towards abstract political concepts [

39]. As a case in point, research on attitudes towards European integration shows that scholars tend to underestimate the proportion of citizens who are neither pro-European nor Eurosceptic [

40]. Therefore, if scholars fail to establish what citizens want from democracy, it might be due to the fact that many citizens do not have strong or detailed opinions about procedural alternatives to representative politics [

41].

Drawing from the literature on stealth democracy, we expected to identify a group of “disengaged democrats” who support alternatives to politics as usual but do not want to be more involved in political decision-making. Contrary to expectations, the latent profile analysis did not identify individuals who combined high levels of support with low intentions to participate. Among those who support the use of DMPs for local policymaking, there may be some respondents who report false intentions to participate in order to appear more “desirable”. Or, it maybe that disengaged democrats are actually indifferent or critical of DMPs, preferring more direct and less demanding ways of influencing politics, such as referendums. Indeed, many of the socio-demographic and attitudinal characteristics expected for disengaged democrats were shared by those identified as indifferent (i.e., lower educated, less politically engaged and less trusting of representative institutions).

Finally, a fourth group which has received limited attention in the literature are the skeptics who are eager to participate, despite rejecting the use of DMPs. The results from Germany and Switzerland show that skeptics are even less supportive of DMPs than critics. Their lack of support is likely explained by the perspective that citizens are not competent enough to perform the functions of elected officials, as skeptics are found to score lower on both anti-elitism and confidence in citizens. However, they would not miss out on an opportunity to decide, as they are higher educated and more interested in politics than most citizens, whom they perceive as “lacking enough sense to tell whether the government is doing a good job”. The finding that skeptics are the highest educated group, echoes previous research demonstrating that education is negatively related to support for instruments incorporating citizens into policymaking [

12,

15,

42]. All in all, the characteristics of this group portrays them as elitists with an “entrustment” conception of politics [

21].

The same four classes were identified in all countries—except the UK where sceptics were missing—suggesting that attitudes towards local DMPs are similarly structured across western European democracies. However, the proportion of respondents falling into each class differed across countries, which might be related to institutional differences. For example, both Germany and the UK are composed of single-member constituencies, generating more electoral losers at the local level. As a result, there may be more citizens seeking additional means of influencing politics in-between elections, potentially explaining why the share of engaged democrats is higher in these countries and why skeptics are missing from the UK. The availability of direct democratic institutions in Switzerland might explain why the critics constitute almost one-fifth of the sample, as critics may not perceive the need for additional means of influencing politics. Finally, the share of skeptics might be greater in the Netherlands since several parties publicly renounced their support for direct citizen participation after the 2016 Ukraine-EU Association Referendum [

42].

10. Conclusions

DMPs have covered a wide range of topics including bioethics, resource scarcities, biodiversity loss and climate change [

43]. Notable examples are the many citizens’ assemblies on climate change held in France (2019–2020), Germany (2015), the UK (2020), Belgium (2020) and Hungary (2020). As argued by other contributors to this special issue, deliberation encourages citizens to consider others’ viewpoints, including those of future generations [

44]. Furthermore, the inclusion of ordinary citizens is crucial for promoting the acceptance of sustainability policies that require a concerted effort from the broader public [

45]. Some authors, such as Graham Smith would even argue that “forms of participatory and deliberative politics offer the most effective democratic response to the current political myopia, as well as a powerful means of protecting the interests of generations to come” [

46] (p. 1). DMPs might therefore be relevant solutions for a more sustainable democracy. However, the capacity of DMPs to deliver long-term solutions depends not only on whether citizens support deliberative innovations, but also on whether they are willing to get involved.

On one hand, our results suggest a promising future for local DMPs. Whereas only a small proportion of citizens in the four Western European democracies examined are critical of local DMPs, around one-third are both supportive and willing to get involved. These “engaged deliberative democrats” are more concerned about the environment than any other issue on the agenda, underscoring the potential of DMPs for influencing policymaking on sustainability issues in a positive direction. Furthermore, DMPs may offer a corrective to the concentration of power in the hands of distant or corrupted elites, at least from the perspective of engaged democrats, who are motivated by stronger feelings of anti-elitism.

On the other hand, the greatest share of citizens in the countries examined (except in Germany where they still constitute 41%) is actually indifferent towards the use of local DMPs. The perceived legitimacy and inclusiveness of DMPs largely depends on whether those who are indifferent can be informed and convinced of the relative merits of deliberative democratic innovations [

47]. Mobilizing this substantial group of apathetic citizens is crucial, as they appear to be the least politically engaged and the least trusting of representative institutions. Finally, among those who are willing to participate, we identified a group of skeptics who reject the use of DMPs for local policymaking, sometimes even more than the critics. Although the skeptics constitute only a small proportion of citizens, they may act as a barrier to democratic innovations, especially if they represent the elite, as suggested by our results.

Therefore, the potential of deliberative innovations for addressing sustainability issues hinges on the ability of practitioners to convince not only the critics, but also the skeptical and indifferent citizens. For example, integrating experts into DMPs might encourage support among the skeptics and relating the issues at hand to everyday life might mobilize those who are indifferent.

11. Limitations and Future Research

Respondents may have found it difficult to judge the merits of DMPs based on hypothetical scenarios, especially as most citizens have probably never participated in one before. However, describing a “real-life” DMP runs the risk of capturing attitudes towards that specific event rather than attitudes towards the general idea of using DMPs to influence policymaking. Furthermore, research has shown that citizens’ preferences for alternative decision-making processes remain relatively stable, even when they are given the opportunity to “think twice” or deliberate about those alternatives [

48].

DMPs come in a variety of shapes and sizes. Therefore, while maintaining the key criteria of citizen participation, random selection and deliberation, we varied the initiators, size, composition, number of topics and outcome of the DMPs described. Although the randomization of attribute levels does not influence a group’s overall support and willingness to participate, some groups may have rated certain attribute levels more favorably than others. For example, skeptics may have rated DMPs initiated by politicians more favorably than those initiated by civil society organizations. Therefore, a further step would be to compare the different groups’ design preferences.

Respondents’ ratings of local DMPs provide a window on citizens’ attitudes towards deliberative alternatives to representative democracy. However, respondents may perceive DMPs as more suitable for dealing with community problems than for addressing issues of national concern such as foreign policy or constitutional reform. Therefore, future research might investigate whether citizens’ attitudes towards DMPs influencing central government decisions are similarly structured using latent profile modelling. Nonetheless, sustainability issues are relevant to local DMPs. For example, in the UK climate assemblies were organized by local authorities from Brighton, Leeds, Oxford, London, and many other cities [

49].

Finally, while the characteristics of the four classes offer insights into the reasons why some citizens are more (or less) inclined towards DMPs, this study has not specifically explored those reasons. Combining the vignettes with a focus group or interviews would provide a more detailed understanding of why respondents pick a specific number out of ten. For example, do citizens position themselves at the mid-point of the scale since they see both the pros and cons of DMPs or since they don’t care much for the subject? The characteristics of indifferent citizens (less politically interested and efficacious) point towards the first explanation, but interrogating this group about their specific concerns and aspirations would provide more certainty.