Abstract

Currently, sustainability emerges as a key element on which the development of competitive advantages for businesses is based. In the dynamic and turbulent environment in which retail companies operate, sustainable practices are posited as an opportunity for their progress and survival. Through this article, it is intended to advance the nature and dimensions of this construct and examine its influence on store equity and consumer satisfaction. Furthermore, this work analyses the moderating effect of gender on these variables and the mediating nature of brand equity in the development of consumer satisfaction. All this is developed through a quantitative study carried out on a sample of 510 consumers of different food retail commercial formats (hypermarkets, supermarkets, and discount stores) in Spain. The technique used for data analysis is partial least squares (PLS) regression. The results show the importance of sustainability and brand equity in the development of consumer satisfaction in the retail sector, with the intensity of its effects being a gender issue. On the other hand, brand equity is positioned as a key element thanks to its mediating effect between sustainability and satisfaction. All of this points to the need to move towards more sustainable business models.

1. Introduction

Given the importance of the social function and the employment generated by the retail trade, it is a strategic sector for the Spanish economy. Data provided by the Research Service of the Department of Economics of the Spanish Confederation of Business Organisations (CEOE) in 2019 underline the major relevance of the retail sector in Spain, where more than 750,000 retail companies are located, representing 13% of the national economy. They account for 17% of the country’s total employment, positioning retail as the largest sector to generate employment.

In addition, its determining role is even greater today due to the immense changes that are taking place in the global economy and that are directly reflected in the retail sector, where digitisation and globalisation play a prominent role. These two factors, together with the evolution in consumer habits, energetically drive the profound transformation process in the Spanish commercial sector, which has also taken an unexpected turn due to the COVID-19 crisis. All these elements lead the retail sector to the inescapable need to reinvent itself if it wants to continue competing efficiently in this unsettled and turbulent environment [1].

To achieve competitive advantages and increase the allure of organisations, sustainability is postulated as a key element to consider [2,3,4,5,6]. Furthermore, the development of sustainable practices by companies, within the social, economic, and environmental spheres, are important factors in attracting consumers to businesses [7,8,9]. Currently, the increasing awareness on the part of consumers in regard to sustainability directly influences the business actions taken by organisations. Consequently, the way companies act can have positive or negative effects on the perceptions that consumers generate towards these establishments [10,11]. In this sense, some studies go further and attempt to link the development of consumer satisfaction to the implementation of sustainable actions in companies. However, in the retail context and considering the consumer’s perspective, there is little empirical evidence that contrasts this relationship [12].

Furthermore, the marketing literature that examines the concept of sustainability highlights its importance in the development of brand equity [13,14,15]. Market research has provided evidence that the brand and related information influence customer evaluations [16,17], suggesting that consumers add value to products through their brand. In this sense, the brand is considered as a differentiating element of the companies with respect to their competitors [18]. Despite the fact that brand equity is a construct traditionally associated with a product or service, its conception has recently led to new approaches, and new conceptualisations of the construct, such as store equity, have emerged [19,20,21].

However, empirical research on the relationships of sustainability with brand equity is in an incipient stage of development, which is accentuated in the retail context by bringing the concept of brand equity to the store environment. In this sense, the importance of the study of brand equity and satisfaction as key elements in the performance of organisations [10,11,13] point out the direction that research on sustainability should be approached [5,6,14,22,23]. Thus, the analysis of the perception that consumers may have about sustainable practices in retail establishments and their impact on store equity and customer satisfaction is postulated as one of the main pillars of this study.

Furthermore, consumer markets are not homogeneous. This idea is in the essence of modern marketing that emphasises the need to observe consumers based on variables that make it possible to differentiate behaviours. From this point of view, gender differences have been a recurring topic of interest in recent years. Efforts to understand gender-moderated differences can be traced back to the last century, although it is from the year 2000 that interest in its study is revitalised in areas such as commitment and loyalty [24], differences in purchasing styles and processes [25,26], perceived value [27], and/or the online environment [28], by way of example of some of the most discussed topics. In this way, the question of how gender can affect the retail sector is presented as a research opportunity by outlining a reality yet to be explored.

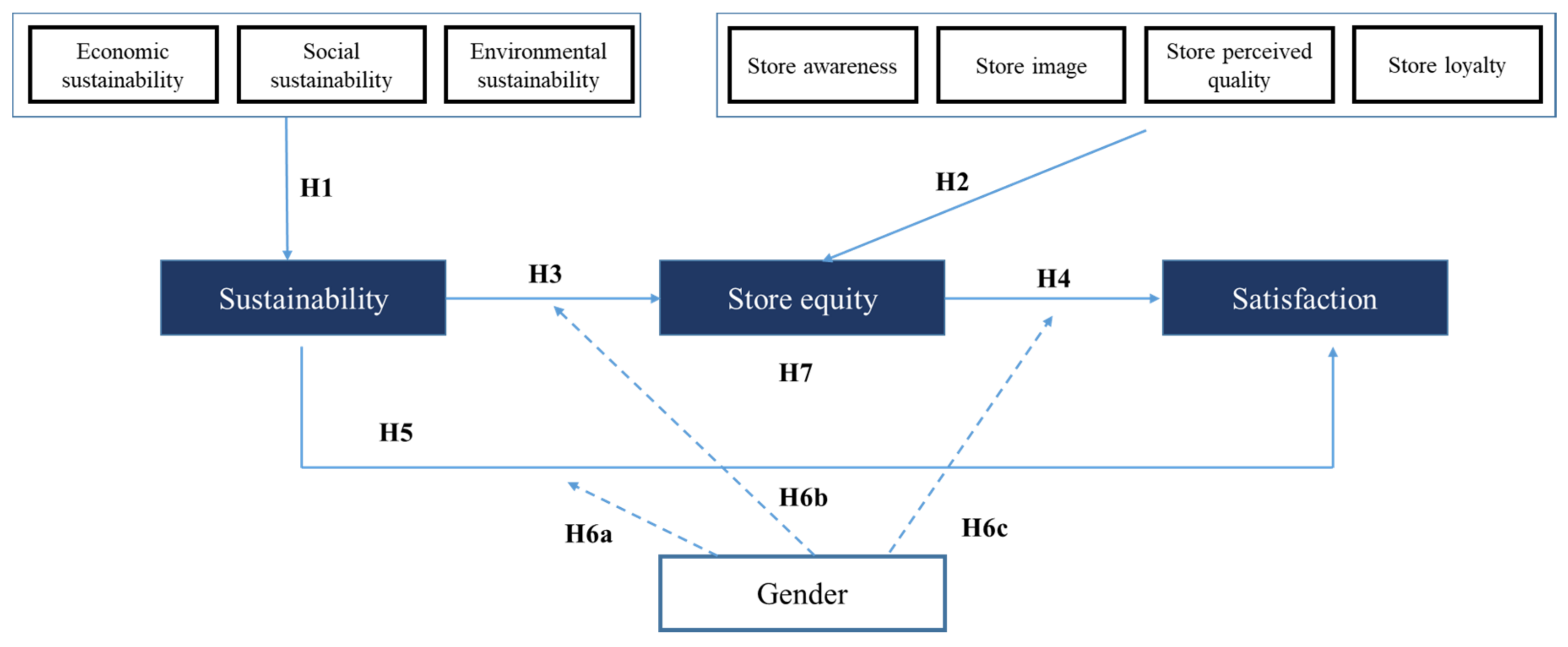

In light of the above, the main objective of this work is to approach the concept of sustainability, identify its nature and scope, and examine its effect on store equity and consumer satisfaction. Additionally, it is intended to observe the mediating nature, between sustainability and satisfaction, of the store’s brand equity, identifying its role in the chain of effects—all this through the prism of defining the moderating effect, or not, of gender in these relationships. In order to achieve the proposed goal, after the introduction, we will examine the main constructs on which this study is based: sustainability, store equity, and consumer satisfaction. Subsequently, the relationships between the variables will be formulated in the form of a hypothesis, and the theoretical model that is postulated will be shown. Next, the methodology of this research and the results derived from data analysis using the partial least squares (PLS)-SEM technique will be presented. Finally, the conclusions derived from the work, as well as their theoretical and managerial implications, will be presented, together with reflections on the limitations and future lines of research.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Sustainability

Sustainability is one of the concepts that has aroused the greatest interest among researchers and academics in the field of marketing in recent years. In this sense, there are many positive effects attributed to it, especially for companies, due to its ability to generate sustainable competitive advantages, thanks to its contribution to changes in consumer perceptions [3,4,5,6].

The Brundtland Commission conceptualised sustainability in 1987 as “the development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [29] (p.40); however, there are still discrepancies today when defining the nature of this variable. In this sense, its dimensional character has been one of the most relevant themes, extensively covered by academic literature. One of the most referenced proposals when addressing the dimensionality of sustainability has been formulated by Elkington [7], who proposes the theoretical model called “Triple Bottom Line” (TBL) in which one of its fundamental pillars is that the success of entrepreneurial businesses will depend on the capacity of organisations to include environmental, social, and economic value in their models. These three dimensions have been explained and defined by the Global Reporting Initiative [30] for use by companies when developing their sustainability reports and implemented both theoretically and empirically in numerous studies. Firstly, the environmental dimension has been explained as the actions taken by companies to create products and services without causing harm to the environment. Secondly, the social dimension is associated with the ability of companies to manage their businesses whilst improving quality of life and reinforcing the relationships that organisations have with the various stakeholders within their environment. Finally, the economic dimension is essential, as it is considered a key requirement for the survival of companies.

Despite the fact that the interest of academics on sustainability in retailing is relatively recent, it is a factor with great potential nowadays due to its versatility and multidisciplinarity due to the different areas of knowledge from which it can be approached (environmental sciences, business, and social sciences). There are different interpretations of sustainability and a wide variety of areas of knowledge in research in the retailing industry. In addition, the research approaches and methods used to analyse sustainability in retailing are varied (for example, theoretical vs. empirical approach, qualitative vs. quantitative methods, descriptive vs. causal analyses), as well as the retail sectors considered by the researchers (e.g., fashion, food, electronics).

Ruiz-Leal et al. [3] identify as preferential study areas of sustainability the analysis of the conditions that must be met for sustainable practices to generate satisfactory results, the selection of organic and ecological products, or the study of sustainable establishments. In addition, another relevant element for retail companies is the image they want to convey to their customers and how they can ensure that their consumers have a better perception of their establishments. In this sense, Ruiz Leal et al. [3] argue that suitable communications of sustainable practices will lead to an improvement in the perception that consumers develop about the sustainable practices implemented by retail stores.

In short, and following the TBL theory formulated by Elkington [7], we postulate in this work that sustainability in retail commercial distribution is built through actions that involve economic sustainability, environmental sustainability, and social sustainability.

2.2. Store Equity

The organisational changes that occurred in the 1980s, as a consequence of the merger, acquisition, and consolidation of companies and brands, have led to increased interest in the study of brand equity [31,32]. In this context, the first brand-oriented research was dominated by the idea that the intangible characteristics associated with brands became a source of tangible wealth, offering a favourable outlook on the development of competitive advantages and earning of future profits. [31].

The literature review allows us to identify three perspectives through which the study of the concept of brand equity has been focused: (a) financial perspective [33]; (b) consumer perspective [18,19,31]; and (c) overall perspective [34,35,36]. The first of the perspectives, the financial one, understands brand equity as an element closely linked to the additional economic benefits obtained by marketing products under a certain brand. The consumer perspective explains brand equity as a construct capable of generating competitive advantages provided that this developed value is perceived by consumers. Finally, the overall perspective defines brand equity as an element in which the company, consumers, distributors, and financial markets are the main stakeholders involved and affected by brand value.

In the context of the retail commercial distribution sector, the brand equity conceptualisation proposal developed by Arnett et al. [19] has been widely accepted among researchers in the field [37]. The model proposed by these authors, following the pattern initially developed by Aaker [31], relies on awareness, image, loyalty, and perceived quality, as basic elements on which to build brand equity, and it starts from the premise that the information obtained in regard to this brand equity can be a source of competitive advantages for the retailer, adopting a formative approach in its conceptualisation and operationalisation. Later, Pappu and Quester [38] analyse the dimensionality of store equity considering the same variables as Aaker [31], finding support to the multidimensional nature of this construct. Awareness, image, perceived quality, and loyalty towards the brand under which the commercial establishment competes are precisely the variables related to store equity which, from the consumer’s perspective, have been most frequently referenced in the marketing literature [18,19,21,31,37,38,39].

Brand awareness is considered the first step towards the creation of brand equity due to its close relationship with the strength of the brand in the memory of consumers [31,35]. Brand image has been defined in a general way as “the sum of beliefs, attitudes, stereotypes, ideas, relevant behaviours or impressions that a person holds with respect to an object, person or organisation” [40] (p. 218), and it is the resulting effect caused by the set of associations that are related to the brand [40]. Depending on whether these associations are positive or negative, the image of the brand will be reinforced, positively or negatively [41]. Perceived quality is also considered as a relevant variable of brand equity, which originates from the overall evaluation that a consumer makes of a service or product once they have tried it and compared it with other products or services [31]. Finally, loyalty is a variable to which particular attention has been paid, as it is considered key in the growth and sustainability of companies due to its ability to retain customers that are loyal not only to the company but also to its brand [36], as represented by its logo. Furthermore, loyalty is a construct that has generated controversy over the years, and there are studies that consider it as an antecedent [5], a dimension [31], or a consequence of brand equity [42,43,44].

Finally, despite the fact that the study of brand equity has been approached from a global perspective, in which some of the dimensions of this construct were considered as antecedents or consequents, the present study follows the brand equity formation proposal formulated by Arnett et al. [19] and Aaker [31] from the consumer perspective; in this study, this variable will be considered as multidimensional, and it is formed from its four basic components: awareness of the store, store image, perceived quality of the store, and loyalty towards the store.

2.3. Satisfaction

Consumer satisfaction, from a marketing perspective, has been considered the key to the success of exchanges, since it is the starting point for customer loyalty. This concept has been a protagonist in the consumer behaviour literature for decades. Although interest in his research has increased since the end of the 1970s, at which time some authors were starting to experience a growing concern for understanding the phenomenon, its antecedents, and its consequences [45], it is the early contribution of Howard and Sheth [46], which marks the origin of this research tradition. Thus, one of the first approximations of the nature, formation, and consequences of satisfaction is due to Howard and Sheth [46], who affirm that satisfaction is the degree of agreement between the current consequences of the purchase and the consumption of the brand, and what is expected of this by the buyer at the time of purchase. Therefore, the consumer will be satisfied if the real consequences are equal to or greater than the expected consequences. In this way, the authors recognise satisfaction as a cognitive response, where the rationality of the individual prevails over the affective aspects.

However, numerous authors have attempted to explain satisfaction from an emotional point of view e.g., [47,48], as it is considered as the individual’s affective response towards a certain act of purchase or consumption of a product or service contextualised within a specific time period.

In any circumstance, where there has been a general consensus, it has been to understand consumer satisfaction from the perspective of results and therefore as a response to an evaluation process as a summary concept. Specifically, Oliver [49] explains it by considering the variety of forms and cognitive interpretations of affect; Westbrook [50] refers to it as a global evaluative judgment, while Fornell [51] associates it with an overall evaluation, and Day [52] associates it with an evaluative response.

3. Hypotheses Development

3.1. Sustainability and Store Equity

The literature analysed has shown little interest to date in examining the relationships between the variables traditionally linked to brand equity and sustainability. However, given the growing role that the development of sustainable practices in the retail environment is acquiring, its potential effect on consumer behaviour and attitudes and on their perception of the brand cannot be ignored.

However, before examining the possible consequences derived from the sustainability–store equity relationship, it is important to clarify how these key constructs are formed. Regarding sustainability, the literature highlights its complexity, both from a conceptual and empirical perspective, so that proposing sustainability as a multidimensional construct is consistent with the accumulated knowledge up to date, and consequently, we expect this variable to be formed by economic sustainability, social sustainability, and environmental sustainability, following the line of work started by Elkington [7]. Similarly, regarding store equity, there are numerous studies that address both its theoretical delimitation and its measurement from a multidimensional approach, considering for this purpose the four key factors on which it is commonly based, namely, awareness, image, perceived quality, and loyalty [19,31,38]. Consequently, we propose the first two hypotheses of this research as follows:

Hypotheses (H1).

Economic sustainability, social sustainability, and environmental sustainability contribute positively and significantly to sustainability.

Hypotheses (H2).

Store awareness, store image, perceived store quality, and store loyalty contribute positively and significantly to store equity.

In the retail context, some sustainable practices carried out by commercial establishments with the aim of improving consumers’ perception of brand equity have been identified [53]. These sustainable practices include, among others: (a) distinction of green and ecological products through changes in their packaging, text content, etc.; (b) promotion of sustainable commercial actions through retailers’ commitment to ethical practices, fair trade, support for Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), etc.; (c) use of keywords and/or ecological symbols with the aim of making consumers aware of the impact that products can have on the environment and society; (d) specific training for employees on organic products so that they can correctly transmit the information to consumers; (e) competitive pricing of organic products so that they are accessible to all consumers; (f) availability and visibility of the products so that consumers can access them with greater guarantees; (g) certification of environmental claims by prestigious institutions and organisations; (h) ecological appeal of the store in creating a greener environment; and (i) participation of agents and stakeholders to increase awareness among all groups that have entered into a relationship with retail companies. The main groups of practices developed in the retail trade correspond to the distinction of green products, the promotion of sustainable business practices, and the availability and visibility of green products [53]. All these actions are aimed at improving the perception that the consumer has towards the commercial establishment and, consequently, it seems plausible to suppose that they have an impact on attitudes and beliefs regarding awareness, image, perceived quality, and loyalty to the store.

In addition, it should be noted that the relationship between sustainability and the variables related to brand equity, on many occasions, is reinforced by the power of innovative decisions implemented by organisations, creating a triple connection between the concepts. In the context of retail trade, Gonzalez-Lafaysse and Lapassouse-Madrid [15] show how the supermarket format in France that makes use of innovative actions linked to sustainable development improves the brand image of its establishments and increases consumer loyalty and purchase intention. Thus, the third of our hypotheses is supported by these reasonings, and therefore, we formulate the following:

Hypotheses (H3).

Customer perceptions of the retailer’s sustainability have a positive effect on store equity.

3.2. Store Equity and Satisfaction

In the study of store equity, the literature shows a limited number of contributions with evidence that looks at the links between brand equity and consumer satisfaction. In a study carried out in the cultural and creative sector in Taiwan, Huang et al. [23] empirically contrast how the increase in overall brand equity contributes to increased consumer satisfaction. Satisfaction is one of the three dimensions that, together with brand equity and brand recall, has significant and positive effects on the consumer’s repeat purchase behaviour. Furthermore, the study carried out by Lassar et al. [54] suggests that brand equity leads to increased customer satisfaction. In the process of generating these positive perceptions, the feelings that nurture the experience and the beliefs about these brands are fundamental and are strongly linked to consumer satisfaction. Along the same lines, Yoo and Park [55] point out that the evaluation that consumers make of the retailers where they purchase the products they consume is based on their experiences with these products. When the value provided by the product they have purchased in the store is higher for customers, their level of satisfaction with the store will also be higher.

In the retail sector, Gil-Saura et al. [37] obtain positive results from the effect of overall brand equity on consumer satisfaction. In this way, they conclude that brand equity acquires special importance, as it is a driver of customer satisfaction towards the retailer.

Thus, the fourth of our hypotheses is supported by these arguments, and therefore, we formulate the following:

Hypotheses (H4).

Customer perceptions of the retailer’s store equity have a positive effect on consumer satisfaction towards the store.

3.3. Sustainability and Satisfaction

Despite the growing interest in the study of sustainability, there is still little evidence in the commercial distribution sector to examine the relationship between sustainability and customer satisfaction. The literature investigating these links has found more evidence in other fields of study in the service sector. Iniesta-Bonillo et al. [56] explore the relationships between the sustainability perceived by visitors in regard to a tourist destination and their perceived value and satisfaction with the trip. The authors structure sustainability as a multidimensional construct based on economic sustainability, social sustainability, and environmental sustainability. The results support the positive and significant relationship between sustainability and satisfaction. Based on these findings, Iniesta-Bonillo et al. [54] argue that sustainability is a key factor in the development of more competitive and market-oriented tourist destinations, due to its ability to build tourist satisfaction. In the same line of research, Cottrell and Vaske [57] confirm that the dimensions of sustainability (economic, social, and environmental) exert a positive and significant effect on tourist satisfaction.

In the field of retail, Marín-García et al. [6] analyse the effect of sustainability on consumer satisfaction, indirectly, through the image and awareness of the store. The authors show sustainability based on the three dimensions postulated by Elkington [7] in his theoretical model of the TBL. In their study, the authors establish the important role of sustainability in the retail sector from the consumer’s perspective, and its effect on satisfaction.

For sectors different from retailing, empirical evidence allows inferring the influence that sustainable practices exert on customer satisfaction [58,59,60]. In this sense, in the tourism sector, some studies have addressed this relationship and have reported how initiatives related to environmental sustainability, such as actions aimed at reducing the negative impact of the daily activities of companies on the environment, have generated an increase in tourist satisfaction [58,61,62]. Tourists welcome these initiatives, as they consider that these actions generate a benefit to society as a whole.

As a consequence of all the above, we postulate the fifth hypothesis of this research:

Hypotheses (H5).

Customer perceptions of the retailer’s sustainability have a positive effect on consumer satisfaction towards the store.

3.4. Moderating Effects of Gender

Regarding studies that have addressed the differences between men and women in relation to the effect of sustainable practices implemented by businesses, no conclusive results have been obtained. While some researchers establish that gender does have a moderating effect on the perception that customers have of sustainable practices implemented by stores [63,64], others have not found significant evidence to justify this effect [65,66].

Regarding the moderating nature of gender in relation to brand equity, some research shows that this sociodemographic factor moderates the impact of some of the variables directly related to brand equity in retail trade [63]. In this sense, gender plays an important role in consumers’ retail buying behaviour, and its effect is more intense in the segment of women than in men. These conclusions are also shared by Borges et al. [67], whose results show significant differences between women and men. In this regard, the authors note that retailers need to carefully consider how store design affects evaluations among male versus female consumers.

Finally, in relation to satisfaction, some studies suggest that this variable is moderated by gender [68,69], influencing consumer behaviour. Atulkar and Kesari [70] have found evidence of the moderating effect of gender on consumer satisfaction in the retail sector. Based on the evidence obtained, they conclude that female consumers are more social, and their buying behaviour, compared to male consumers, is based mainly on the search for pleasure. In other words, consumer satisfaction would be related to a more hedonistic factor.

Considering all the above, we postulate the following hypothesis:

Hypotheses (H6).

In the retail sector, in comparison to male consumers, female consumers show stronger links between (H6a) customer perceptions of the retailer’s sustainability and store equity, (H6b) customer perceptions of the retailer’s store equity and satisfaction, and (H6c) customer perceptions of the retailer’s sustainability have a positive effect and consumer satisfaction towards the store.

3.5. Mediating Effect of Store Equity

To our knowledge, the role of brand equity in the sustainability–satisfaction relationship remains practically unexplored. However, this link could be explained in light of the Theory of Reasoned Action proposed by Ajzen and Fishbein [71]. The authors examine how the grouping of attitudinal and behavioural factors could clarify the behaviours of human beings. Through their theoretical model, they indicate that the benefit perceived by a person or group of people in regard to a stimulus can determine the assessments or judgments made by individuals in a given situation. Furthermore, depending on how this benefit is considered to be, it is possible that people’s expectations vary.

Following the model proposed by Ajzen and Fishbein [71], the last hypothesis of this research is proposed. In this sense, sustainability is considered as a variable of a cognitive nature and satisfaction is considered as a variable with a more affective nature, and thus, it is intended to examine whether the perception and/or acceptance of sustainable practices implemented by retail companies generate changes in consumer satisfaction in the presence or absence of store equity brand.

Moreover, following the stakeholder theory [72], Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives may lead to an improved brand image for customers, employees, and other stakeholders, indicating that such activities may ultimately improve customer satisfaction. Notwithstanding, Carroll et al. [73] argue that firms should understand that the outcomes of CSR depend largely on mediating variables, and therefore, the influence of CSR initiatives on customer satisfaction may be indirect. In this sense, previous research has concluded that brand image mediates the relationship between CSR and customer satisfaction in the hotel industry [74,75]. Bearing in mind that brand image is a dimension of store equity [19] and the similarities between CSR and Corporate Sustainability [76], we extrapolate the evidence observed in the hotel industry to posit the mediating role of store equity in the relationship between retailer’s sustainability and customer satisfaction. Therefore, we postulate the following:

Hypotheses (H7).

The effect of sustainability on consumer satisfaction is positively mediated by store equity.

Figure 1 shows the research model that gathers together the relationships raised in the previous hypotheses.

Figure 1.

Proposed research model.

4. Methodology

To achieve the objective proposed in this research, an empirical study of a quantitative nature was carried out (Table 1). Specifically, a structured ad hoc questionnaire was used. The fieldwork was carried out during the months of April and May 2017 in the city of Valencia. Potential interviewees were approached at the entrances to three types of retail formats: hypermarkets, supermarkets, and discount stores. Grocery store chains were selected according to their assortment and their positioning as well as their wide presence in the Spanish market. The sample of consumers was obtained following a non-probabilistic quota sampling procedure in terms of gender and age. A filter question was asked to potential interviewees to assure that they patronise that store and, therefore, they are familiar with that retailer’s offerings. Furthermore, the measurement scales used (see the Appendix A) in this study have been tested and validated in previous works carried out in similar contexts [5,6]. To measure sustainability, we used the scale proposed by Lavorata [13]. On the other hand, the scale used to measure store equity was adapted from the one proposed by Yoo et al. [77]. Finally, the Bloemer and Odekerken-Schröder one-dimensional scale [78] was the basis for measuring consumer satisfaction in the establishment.

Table 1.

Technical information.

A total of 510 valid questionnaires were obtained (170, hypermarkets; 170, supermarkets; 170, discount stores). In order to enable comparative analyses with balanced samples, the same number of questionnaires was collected for each retail format. The distribution of the sample is presented in Table 2. More than half (59.6%) correspond to women, while 40.4% are men. Regarding the age range, it is noteworthy that almost 70% of the sample groups are consumers between 36 and 65 years old. Regarding the level of education, almost half of the sample (46.7%) claim to have higher education qualifications. Finally, 67.7% of those surveyed claim to be working.

Table 2.

Sample distribution: sociodemographic variables.

The analysis of the results of this study was carried out through the partial least squares (PLS) technique. This type of technique can be used for both confirmatory and exploratory studies [79,80]. Furthermore, this type of analysis makes it possible to contrast theoretical assumptions with empirical data, as is the intention of this study. Specifically, in this research, the analysis of the results was carried out in two stages.

This technique has been used extensively in recent years by researchers in the context of marketing [81]. Cassel et al. [82] point out that PLS-SEM is a technique characterised by its robustness mainly in three situations: skewed distributions in the manifest variables; multi-collinearity both between latent constructs and between indicators; and inaccurate specification of the structural model. Furthermore, Fornell and Bookstein [83] explain that PLS allows avoiding two important problems: firstly, inadmissible or improper solutions such as negative estimates of the variance of the indicators and standardised loadings greater than 1 and, secondly, the indeterminacy of factors thanks to the fact that the PLS technique explicitly defines the latent variables, making it easier to obtain the scores of the factors or latent variables. Moreover, it has been used successfully in studies carried out in the context of retailing [5,6]. The PLS-SEM analysis is a non-parametric statistical procedure, for which the data do not need to be normally distributed [80]. Although it is not possible to apply significance parameters as in the case of regressions to check if the loadings are significant, through the PLS-SEM analysis, we can test the significance of the factor loadings and paths using the non-parametric bootstrap procedure [84]. Firstly, the measurement instrument was validated. Subsequently, the estimation of the structural model defined in this study was carried out.

5. Results

With the aim of examining the validity and reliability of the measurement instrument used in this research, we calculated a path weighting scheme from a PLS algorithm with a parameter of 300 maximum interactions, all of this using the PLS-SEM technique. Through this procedure, we obtained for each of the study factors the necessary information on the factor loadings, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, composite reliability index (CRI), and average variance extracted (AVE). All these data are collected in Table 3. In order to achieve high levels of reliability and validity of the measurement instrument, we eliminated those items with loadings lower than 0.7 [85,86]. Specifically, the items related to store image IM3, IM4, and IM5 were eliminated from the causal model (see Appendix A).

Table 3.

Measurement instrument of the structural model: reliability and convergent validity.

The data from Table 3 show satisfactory results for Cronbach’s α, exceeding 0.7, and oscillating between 0.8 and 0.9, which are recommended values according to the criteria of Nunnally and Bernstein [87]. On the other hand, the results obtained from the composite reliability far exceed the minimum required, 0.7 [88], so they can be considered very satisfactory. Regarding the average variance extracted, all the constructs of the structural model obtain values greater than 0.5, which implies that each factor explains at least 50% of the variance of the assigned indicators [88]. All this allows us to confirm the reliability and validity of the measurement instrument. In addition, Table 4 examines the discriminant validity using the criterion proposed by Fornell and Larcker [89]. The results obtained show that the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) is higher than the estimated correlation between the factors, which appears below the diagonal of the matrix, corroborating the discriminant validity.

Table 4.

Measurement instrument: discriminant validity (Fornell–Larcker criterion).

When considering both sustainability and store equity as second-order constructs, formed by formative items, we analyse their weights. Following the criteria of Diamantopoulos and Winklhofer [90], it is possible to confirm the absence of collinearity, since the variance inflation factor (VIF) for the dimensions of the second-order constructs is less than the critical level of 5 (Table 5).

Table 5.

Parameter estimates of the formative second-order constructs.

In addition, the results for the weights of the first-order constructs on their corresponding second-order constructs displayed in Table 5 allow us to support the first two hypotheses of this research. In relation to the first hypothesis, which posits the positive contribution of the economic, social, and environmental dimensions of sustainability to the second-order construct of sustainability, it is observed that the influence of the three dimensions on the second-order construct is significant and similar, being greater the effect of social sustainability than the contribution of the other two dimensions on sustainability. Regarding the second hypothesis that states the positive impact of the dimensions of store equity (awareness, image, perceived quality, and loyalty), on the second-order construct, it is observed that store awareness and perceived store quality have a stronger effect on brand equity than store loyalty and store image.

Once the measurement instrument used for the evaluation of each of the constructs included in the proposed theoretical model has been evaluated, and its reliability and validity confirmed through the results obtained, the structural model is estimated. In this sense, for the analysis of the proposed structural model, we used the SmartPLS software once again with complete bootstrapping with 5000 subsamples [91] to evaluate the causal relationships that make up the model hypotheses and their significance, in addition to obtaining the results of the values of the R2 explained variance. Furthermore, through the blindfolding technique, we obtain the results provided by the predictive relevance criterion of the Q2 test. Table 6 shows the results of the estimation of the structural model in this research.

Table 6.

Causal relationships estimation.

The results obtained from the PLS-SEM analysis allow us to accept all the relationships proposed by the causal model. Regarding the third of the proposed relationships, we can affirm the positive and significant effect of sustainability on store equity (β3 = 0.208, p < 0.001). Likewise, this work’s fourth hypothesis confirms the effect of store equity on consumer satisfaction, obtaining a positive and significant result (β4 = 0.600, p < 0.001). Finally, we can also confirm the significant and positive effect of sustainability on satisfaction (β5 = 0.589, p < 0.001).

On the other hand, to respond to the set of hypotheses that make up H6 in this research, a multi-group analysis was carried out using the PLS-MGA method. The results shown in Table 7 indicate the existence of significant and positive differences for H6b. That is, we can confirm that the relationship between store equity and consumer satisfaction is moderated by gender. Moreover, the chain “sustainability → store equity → satisfaction” is only observed for female consumers, whereas for men, there is no statistically significant influence of sustainability on store equity, in support of the higher importance of intangible and/or hedonic aspects in consumer perceptions for women in comparison to men. Additional evidence of these differences in perceptions between male and female consumers is provided by the comparisons of the mean values for each item of the questionnaire (see the Appendix A), which reveal the existence of significant differences in the scores of several items measuring social sustainability, store awareness, image, perceived quality, and store loyalty, being in all cases higher for female consumers in comparison to male customers. All these results are consistent with those studies that suggest that in retail trade, when making decisions, it is relevant to consider gender given the differences between men and women in perception and purchase intention [67,68,69].

Table 7.

Results of the multigroup analysis.

Finally, the analysis of the role of brand equity as a mediating variable between sustainability and customer satisfaction was carried out using the Preacher and Hayes bootstrapping method [92]. Table 8 shows that the direct and indirect effect between sustainability and satisfaction is significant. In this sense, it is possible to accept hypothesis H7, since brand equity is a mediator of the sustainability–satisfaction relationship. Furthermore, we can confirm through the VAF result, which determines the size of the indirect effect in relation to the total effect [93], that brand equity has a partial mediating effect on the relationship (0.615).

Table 8.

Summary of mediating effect test.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

The results achieved in this research reveal important findings that allow us to present certain theoretical implications. Firstly, the evidence obtained allows us to conclude that in retail, sustainability is a multidimensional construct that can be treated as second-order. Specifically, sustainability in retail is aligned with the basic principles of the TBL model, which is composed of the three basic dimensions of economic, environmental, and social sustainability [7]. In this sense, it is relevant to note that in retailing, the weights of the dimensions of sustainability on this construct are similar, being the contribution of social sustainability to the formation of sustainability slightly higher than the ones of the other two dimensions.

Secondly, the results of this study reflect the importance of sustainability as a fundamental pillar in retail trade strategy [3,4,5,6], given its positive impact on store equity and on customer satisfaction towards the establishment [5,55]. In this sense, these findings allow us to advance in the knowledge of these variables and invite us to look beyond customer satisfaction to observe their links with other variables such as trust and/or Electronic Word of Mouth (eWOM) [88].

Thirdly, our results show that store equity has a multidimensional nature and that this nature is well represented in terms of awareness, image, perceived quality, and loyalty, supporting the line of work of Arnett et al. [19]. The results obtained in this research show that awareness and perceived quality are the factors that most contribute to the construction of the store equity in retailing. In contrast, store image and loyalty emerge as secondary elements in the construction of store equity. All in all, the four dimensions of store brand equity are key in building the store equity second-order construct that, in turn, influences positively on consumer satisfaction towards the retail store. Thus, brand equity is positioned as a key element in fostering customer satisfaction [23]. Given its nature as a partial mediator, store equity is a decisive variable in business strategy, since it provides substantive information on how sustainable practices affect customer satisfaction. Perceptions regarding the sustainable initiatives implemented by the retailer generate direct and mediated effects, through the store’s equity, on customer satisfaction. Consequently, an important contribution has been made by providing information about how and why the effect of such perceptions on customer satisfaction occurs: to the extent that it is the inclusion of brand equity in the equation that intensifies its explanatory power.

Finally, our conclusion regarding the moderating role of gender revealed in this work is of particular interest, since it highlights the need to retain variables of a sociodemographic nature when analysing consumer behaviour in the retail sector [71]. Results indicate that the intensity of the observed relationships is affected by gender and that there are notable differences between men and women, especially when considering the contribution of sustainability to the store equity and store equity to the satisfaction experienced by women, given its greater influence. The findings provide evidence on the interaction between gender and the chain of effects “sustainability→ store equity → satisfaction”. One possible explanation is the fact that women are more pleasure-oriented when shopping, whereas men are more task-oriented, which consequently influences shopping behaviour outcomes [94], as far as the differences in gender are mainly observed in how store equity is built, and more specially, in consumer perceptions on store quality. All this confirms the key influence of gender on shopping behavior; and our findings are aligned with the results of other studies evidencing that men and women perceive the shopping activity differently [95], observing these differences not only with hedonic products but also with utilitarian purchases such as groceries. Therefore, to generate satisfaction towards the retailer, it is not only important to consider the factors related to store equity, but also to pay special attention to other variables influencing this variable, given the observed differences between male and female consumers.

All in all, the findings of this study allow us to conclude that there is a need to implement sustainable practices in the food retail trade, since their influence on customer satisfaction has been proven, regardless of gender. However, the role of store equity is even more important in the case of women compared to men, and it plays a more active role in the achievement of said satisfaction. In particular, it would be beneficial for store managers to actively promote and include ecological and fair trade products as part of their range, engage the company in humanitarian actions, encourage the use of public transport by employees, promote reduced energy consumption, recycling or elimination of plastic packaging for some products and/or its replacement with biodegradable materials. Currently, there are movements such as “Fridays for Future” that aim to raise awareness in society of the importance of taking action to prevent climate change and global warming. Movements such as this support responsible consumption by consumers, as well as the development of sustainable productive activities by companies, causing the least possible damage to society and the environment. In addition, as a consequence of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) crisis, many commercial establishments will be forced to make decisions, probably innovative and sustainable, to adapt their businesses to this new reality. In this way, it seems clear that, operating in the dimensions of environmental, social, and economic sustainability, customers will be more satisfied with the retail establishment.

In addition, as far as sustainability is concerned, a key element to improve the perception that consumers have of retail establishments is communication. Thus, companies should use the tools that allow them to reach their target audience (social media, brochures, etc.), so that the message they want to convey is correctly received. In this sense, if the preferred channel to communicate with their audience is social media, it is important to know what profile of person interacts with each type of social media, and to adapt the message to the audience and the used social media. In this sense, it is important that the image that the company conveys to its target does not show inconsistencies. Thus, for instance, if the retail establishment wishes to convey an image linked to sustainability, the green colour and graphical elements associated with this concept should appear in all its communications.

It also seems evident that to achieve consumer satisfaction, sustainable practices implemented by organisations must be accompanied by actions linked to the creation of brand equity. In this sense, enhancing the consumer’s shopping experience through the development of attractive in-store promotions, new loyalty programs, improvements in the store environment, or better training for employees, could be some of the measures to be implemented in retail establishments. All of this, whilst collaborating more closely with the consumer when developing actions such as those above mentioned, will help to increase customer satisfaction.

Finally, it is necessary to indicate that the results obtained give rise to opportunities for future lines of research. In relation to the variables that could explain the effect of sustainable practices on consumer satisfaction, trust, eWOM, or commitment to the retailer could be factors to consider when attempting understanding of the mechanisms through which sustainability generates links between customers and retailers. Similarly, other moderating variables could be analysed, such as the customer age, education, occupation, or behavioural variables (purchase frequency) that can help explain how the effects of sustainability intensify in the development of satisfaction. In addition, the study of the differences in the perceptions that consumers from other regions have towards the sustainable practices of retail businesses and if these differences may be influenced by aspects such as culture, lifestyle, or commercial structure, could also manifest as a future line of research. On the other hand, the analysis of possible differences in consumer perceptions of the commercial formats in this study would be another possible future route that helps to explain the nature of sustainability in retail. Additionally, this analysis could also be extended to examine the differences between the brands in this research or the study of sectors other than food.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, A.M.-G., M.E.R.-M., I.G.-S. and G.B.-C.; Methodology, A.M.-G., M.E.R.-M., and I.G.-S.; Validation, A.M.-G., M.E.R.-M., and I.G.-S.; Formal Analysis, A.M.-G., M.E.R.-M., and I.G.-S.; Investigation, A.M.-G., M.E.R.-M., and I.G.-S.; Data Curation, A.M.-G.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, A.M.-G., M.E.R.-M., I.G.-S., and G.B.-C.; Writing—Review and Editing, A.M.-G., M.E.R.-M., and I.G.-S.; Visualisation, A.M.-G., M.E.R.-M., and I.G.-S.; Supervision, M.E.R.-M., and I.G.-S.; Project Administration, I.G.-S. and G.B.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This paper was developed within the Research Project ECO2016-76553-R of the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness (National Research Agency).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Items included in the questionnaire: p values for comparisons of mean values.

Table A1.

Items included in the questionnaire: p values for comparisons of mean values.

| Factor | Item | Male | Female | ANOVA p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Sustainability | SN1 | STORE X pays producers a fair price. | 4.06 | 4.13 | 0.499 |

| SN2 | STORE X pays its employees a decent wage. | 4.02 | 4.18 | 0.156 | |

| SN3 | STORE X pays its employees a minimum wage in developing countries. | 4.07 | 4.05 | 0.807 | |

| SN4 | STORE X monitors the working conditions of its employees. | 4.16 | 4.08 | 0.442 | |

| Social Sustainability | SN5 | STORE X sells fair trade products. | 4.00 | 4.02 | 0.838 |

| SN6 | STORE X sells organic products. | 4.55 | 4.86 | 0.035 * | |

| SN7 | STORE X implements humanitarian actions. | 4.54 | 4.61 | 0.581 | |

| SN8 | STORE X engages in actions directed at schools. | 4.50 | 4.62 | 0.296 | |

| SN9 | STORE X sells share products (donations to charitable associations). | 4.55 | 4.86 | 0.025 * | |

| Environmental Sustainability | SN10 | STORE X recycles their products and packaging. | 4.23 | 4.35 | 0.245 |

| SN11 | STORE X cuts back their consumer of electricity. | 4.31 | 4.32 | 0.947 | |

| SN12 | STORE X pays attention to the environment. | 4.56 | 4.70 | 0.197 | |

| Store awareness | AW1 | I am aware of [store name] stores. | 5.13 | 5.47 | 0.007 * |

| AW2 | I can recognize [store name] stores among other competing stores. | 5.76 | 5.67 | 0.464 | |

| AW3 | Some characteristics of [store name] stores come to mind quickly. | 5.37 | 5.52 | 0.299 | |

| AW4 | I have difficulty in imagining [store name] stores in my mind. | 5.14 | 5.13 | 0.958 | |

| Store image | IM1 | STORE X has friendly personnel. | 5.50 | 5.73 | 0.034 * |

| IM2 | STORE X has extensive assortment. | 5.19 | 5.45 | 0.064 | |

| IM3 | STORE X can easily be reached. | 5.36 | 5.90 | 0.000 * | |

| IM4 | STORE X offers value for money. | 5.50 | 5.61 | 0.223 | |

| IM5 | STORE X has a nice atmosphere. | 5.28 | 5.31 | 0.810 | |

| IM6 | STORE X has attractive promotions in the store. | 4.95 | 5.40 | 0.000 * | |

| IM7 | STORE X provides excellent customer service. | 5.07 | 5.28 | 0.043 * | |

| IM8 | STORE X offers an attractive loyalty program. | 4.33 | 4.63 | 0.033 * | |

| Store perceived quality | PQ1 | The likely quality of STORE X is extremely high. | 4.51 | 4.81 | 0.016 * |

| PQ2 | [store name] stores provide excellent service to its customers. | 4.42 | 4.91 | 0.000 * | |

| PQ3 | [store name] stores are known for their excellent service. | 4.10 | 4.75 | 0.000 * | |

| PQ4 | [store name] stores perform service right the first time. | 4.46 | 5.09 | 0.000 * | |

| Store loyalty | LO1 | I consider myself to be loyal to [store name] stores. | 4.07 | 4.68 | 0.000 * |

| LO2 | When buying groceries [store name], stores are my first choice. | 4.30 | 4.94 | 0.000 * | |

| LO3 | I will not buy from other groceries retailers if I can buy the same item at [store name] stores. | 3.85 | 4.44 | 0.000 * | |

| LO4 | Even when items are available from other retailers, I tend to buy from [store name] stores. | 3.89 | 4.13 | 0.119 | |

| Satisfaction | SF1 | STORE X confirms my expectations. | 4.83 | 4.90 | 0.517 |

| SF2 | I am satisfied with price/quality ratio of STORE X. | 4.97 | 4.93 | 0.765 | |

| SF3 | I am really satisfied with STORE X. | 4.97 | 4.96 | 0.989 | |

| SF4 | In general, I am satisfied with STORE X. | 5.19 | 5.19 | 1.000 | |

| SF5 | In general, I am satisfied with the products I get from STORE X. | 5.43 | 5.33 | 0.313 | |

Notes: Values in bold are comparisons of the mean values * Statistically significant at p < 0.05.

References

- Confederación Española de Organizaciones Empresariales. 1. El Sector Comercio en la Economía Española; Confederación Española de Organizaciones Empresariales—CEOE: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Arcese, G.; Flammini, S.; Lucchetti, M.C.; Martucci, O. Evidence and experience of open sustainability innovation practices in the food sector. Sustainability 2015, 7, 8067–8090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Real, J.L.; Uribe-Toril, J.; Gázquez-Abad, J.C.; de Pablo Valenciano, J. Sustainability and retail: Analysis of global research. Sustainability 2019, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-García, A.; Gil-Saura, I.; Ruiz-Molina, M.E. Influence of commercial format on sustainability in grocery retailing in Spain. UCJC Bus. Soc. Rev. 2019, 16, 132–173. [Google Scholar]

- Marín-García, A.; Gil-Saura, I.; Ruíz-Molina, M.E. How do innovation and sustainability contribute to generate retail equity? Evidence from Spanish retailing. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2020, 29, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-García, A.; Gil-Saura, I.; Ruíz-Molina, M.E. How does sustainability affect consumer satisfaction in retailing? In Social and Sustainability Marketing: A Casebook for Reaching Your Socially Responsible Consumers through Marketing Science; Taylor&Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2020; In press. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Enter the triple bottom line. In The Triple Bottom Line: Does it All Add Up? Assessing the Sustainability of CSR; Henriques, A., Richardson, J., Eds.; Earthscan Publications: London, UK, 2004; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Morioka, S.N.; Evans, S.; de Carvalho, M.M. Sustainable business model innovation: Exploring evidences in sustainability reporting. Procedia CIRP 2016, 40, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Freudenreich, B.; Schaltegger, S.; Saviuc, I.; Stock, M. Sustainability-oriented business model Assessment-A conceptual foundation. In Analytics, Innovation and Excellence-Driven Enterprise Sustainability; Edgeman, R., Carayannis, E., Sindakis, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 169–206. [Google Scholar]

- Finn, A.; Louviere, J. Shopping-center patronage models: Fashioning a consideration set segmentation solution. J. Bus. Res. 1990, 21, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGoldrick, P.J.; Thompson, M.G. The role of image in the attraction of the out-of-town centre. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 1992, 2, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Hernández, A.; Olavarría-Jaraba, A.; Valera-Blanes, G.; Vázquez-Carrasco, R. Sustainability and branding in retail: A model of chain of effects. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavorata, L. Influence of retailers’ commitment to sustainable development on store image, consumer loyalty and consumer boycotts: Proposal for a model using the theory of planned behaviour. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 1021–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Lafaysse, L.; Lapassouse-Madrid, C. Facebook and sustainable development: A case study of a French supermarket chain. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2016, 44, 560–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappu, R.; Quester, P.G. How does brand innovativeness affect brand loyalty? Eur. J. Mark. 2016, 50, 2–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.R.; Monroe, K.B. The effect of price, brand name, and store name on buyers’ perceptions of product quality: An integrative review. J. Mark. Res. 1989, 26, 351–357. [Google Scholar]

- Dawar, N.; Parker, P. Marketing universals: Consumers’ use of brand name, price, physical appearance, and retailer reputation as signals of product quality. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, B.; Donthu, N.; Lee, S. An examination of selected marketing mix elements and brand equity. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, D.B.; Laverie, D.A.; Meiers, A. Developing parsimonious retailer equity indexes using partial least squares analysis: A method and applications. J. Retail. 2003, 79, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappu, R.; Quester, P.G.; Cooksey, R.W. Consumer-based brand equity and country-of-origin relationships. Eur. J. Mark. 2006, 40, 696–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Saura, I.; Šerić, M.; Ruiz-Molina, M.E.; Berenguer-Contrí, G. The causal relationship between store equity and loyalty: Testing two alternative models in retailing. J. Brand Manag. 2017, 24, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantano, E.; Timmermans, H. What is smart for retailing? Procedia Environ. Sci. 2014, 22, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.W.; Li, Y.H.; Yen, M.T. The relationship between green innovation and business performance-the mediating effect of Brand image. Xing Xiao Ping Lun 2016, 13, 89. [Google Scholar]

- Abubakara, A.M.; Ilkan, M.; Meshall Al-Tal, R.; Kolawole Eluwole, K. EWOM, revisit intention, destination trust and gender. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 31, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotzé, T.; North, E.; Stols, M.; Venter, L. Gender differences in sources of shopping enjoyment. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dommer, S.L.; Swaminathan, V. Explaining the endowment effect through ownership: The role of identity, gender, and self-threat. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 39, 1034–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Wen, C.; George, B.; Prybutok, V.R. Consumer heterogeneity, perceived value, and repurchase decisión-making online shopping: The role of gender, age, and shopping motives. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2016, 17, 116–131. [Google Scholar]

- Peña, N.; Gil-Saura, I.; Rodríguez-Orejuela, A. Emotion and reason: The moderating effect of gender in online shopping behavior. Innovar 2018, 28, 117–131. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland, G.H. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; World Commission on Environment and Development; Oxford: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). Global Reporting Initiative. 2017. Available online: http://database.globalreporting.org/search (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Aaker, D.A. Managing Brand Equity: Capitalizing on the Value of a Brand Name; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Seetharaman, A.; Nadzir, Z.A.B.M.; Gunalan, S. A conceptual study on brand valuation. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2001, 10, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, C.J.; Sullivan, M.W. The measurement and determinants of brand equity: A financial approach. Mark. Sci. 1993, 12, 28–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farquhar, P.H. Managing brand equity. Mark. Res. 1989, 1, 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarejo Ramos, ÁF. Modelos multidimensionales para la medición del valor de marca. Investigaciones Europeas en Dirección y Economía de la Empresa 2002, 8, 13–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Saura, I.; Ruiz-Molina, M.E.; Michel, G.; Corraliza-Zapata, A. Retail brand equity: A model based on its dimensions and effects. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2013, 23, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappu, R.; Quester, P. A consumer-based method for retailer equity measurement: Results of an empirical study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2006, 13, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buil, I.; Martínez, E.; De Chernatony, L. Medición del valor de marca desde un enfoque formativo. Cuadernos de Gestión 2010, 10, 167–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanger, C.; Mount, J.; Wilson, M. Institutional image and retention. Tert. Educ. Manag. 2002, 8, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Brand equity management in a multichannel, multimedia retail environment. J. Interact. Mark. 2010, 24, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jara, M.; Cliquet, G. Retail brand equity: Conceptualization and measurement. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2012, 19, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselmsson, J.; Burt, S.; Tunca, B. An integrated retailer image and brand equity framework: Re-examining, extending, and restructuring retailer brand equity. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 38, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinfeng, W.; Zhilong, T. The impact of selected store image dimensions on retailer equity: Evidence from 10 Chinese hypermarkets. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2009, 16, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, H.K. A CS\D & CB Bibliography-1982. In International Fare in Consumer Satisfaction and Complaining Behavior; Ralph, L., Keith Hunt, H., Eds.; Indiana University School of Business: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1983; pp. 132–155. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, J.A.; Sheth, J.N.Y. The Theory of Buyer Behavior; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Cadotte, E.R.; Woodruff, R.B.; Jenkins, R.L. Expectations and norms in models of consumer satisfaction. J. Mark. Res. 1987, 24, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halstead, D.; Hartman, D.; Schmidt, S.L. Multisource effects on the satisfaction formation process. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1994, 22, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer; McGraw-Kill: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Westbrook, R.A. Intrapersonal affective influences on consumer satisfaction with products. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 7, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C. A national customer satisfaction barometer: The swedish experience. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, R.L. Modeling choices among alternative responses to dissatisfaction. In Advances in Consumer Research; William, D., Perreault, D., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1984; pp. 496–499. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P. Greening retail: An Indian experience. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2014, 42, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassar, W.; Mittal, B.; Sharma, A. Measuring customer-based brand equity. J. Consum. Mark. 1995, 12, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.; Park, M. The effects of e-mass customization on consumer perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty toward luxury brands. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5775–5784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iniesta-Bonillo, M.A.; Sánchez-Fernández, R.; Jiménez-Castillo, D. Sustainability, value, and satisfaction: Model testing and cross-validation in tourist destinations. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5002–5007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, S.P.; Vaske, J.J. A framework for monitoring and modeling sustainable tourism. E Rev. Tour. Res. 2006, 4, 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.L.; Mattila, A.S. Improving consumer satisfaction in green hotels: The roles of perceived warmth, perceived competence, and CSR motive. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 42, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Gursoy, D. Influence of sustainable hospitality supply chain management on customers’ attitudes and behaviors. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 49, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moise, M.S.; Gil-Saura, I.; Ruiz-Molina, M.E. “Green” practices as antecedents of functional value, guest satisfaction and loyalty. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2020. In press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moise, M.S.; Gil-Saura, I.; Šerić, M.; Ruiz Molina, M.E. Influence of environmental practices on brand equity, satisfaction and word of mouth. J. Brand Manag. 2019, 26, 646–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moise, M.S.; Gil-Saura, I.; Ruiz-Molina, M.-E. Effects of green practices on guest satisfaction and loyalty. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 92–104. [Google Scholar]

- Das, G. Impacts of retail brand personality and self-congruity on store loyalty: The moderating role of gender. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, G.; Schaarschmidt, M.; Ivens, S. Effects of customer-based corporate reputation on perceived risk and relational outcomes: Empirical evidence from gender moderation in fashion retailing. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2017, 26, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, A.; Costa, R.; Rosati, F. Gender differences in customer expectations and perceptions of corporate social responsibility. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 116, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassinis, G.; Panayiotou, A.; Dimou, A.; Katsifaraki, G. Gender and environmental sustainability: A longitudinal analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2016, 23, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, A.; Babin, B.J.; Spielmann, N. Gender orientation and retail atmosphere: Effects on value perception. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2013, 41, 498–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P. Understanding the effect of customer relationship management efforts on customers retention and customer share development. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karande, K.; Magnini, V.P.; Tam, L. Recovery Voice and Satisfaction after Service Failure. An Experimental Investigation of Mediating and Moderating Factors. J. Serv. Res. 2007, 10, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atulkar, S.; Kesari, B. Satisfaction, loyalty and repatronage intentions: Role of hedonic shopping values. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 39, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, E.R. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B.; Shabana, K.M. The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Rashid, B. A conceptual model of corporate social responsibility dimensions, brand image, and customer satisfaction in Malaysian hotel industry. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 39, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, A.; Amir, A. CSR Dimensions and Customer Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Brand Image from the Perspective of the Hotel Industry. Eur. Online J. Nat. Soc. Sci. Proc. 2019, 8, 184. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, M.M.; Bergman, Z.; Berger, L. An empirical exploration, typology, and definition of corporate sustainability. Sustainability 2017, 9, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, B.; Donthu, N. Developing and validating a multidimensional consumer-based brand equity scale. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 52, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloemer, J.; Odekerken-Schröder, G. Store satisfaction and store loyalty explained by customer and store related factors. J. Consum. Satisf. Dissatisfaction Complain. Behav. 2002, 15, 68–80. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 33, 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Southend Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hänseler, F.S.; Lam, W.H.; Bierlaire, M.; Lederrey, G.; Nikolić, M. A dynamic network loading model for anisotropic and congested pedestrian flows. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2017, 95, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassel, C.; Hackl, P.; Westlund, A.H. Robustness of partial least-squares method for estimating latent variable quality structures. J. Appl. Stat. 1999, 26, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Bookstein, F.L. Two structural equation models: LISREL and PLS applied to consumer exit-voice theory. J. Mark. Res. 1982, 19, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, B.; Tibshirani, R. Bootstrap methods for standard errors, confidence intervals, and other measures of statistical accuracy. Stat. Sci. 1986, 1, 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychological Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modelling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Winklhofer, H.M. Index construction with formative indicators: An alternative to scale development. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J. SmartPLS 3. Bönningstedt: SmartPLS. GmbH. 2015. Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S.A.; Darzi, M.A.; Bhat, S.U. Sustainable Business Model in B2C Online Retailing: An Indian Consumer Perspective. In Technological Innovations for Sustainability and Business Growth; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 147–185. [Google Scholar]

- Maurer Herter, M.; Pizzutti dos Santos, C.; Costa Pinto, D. “Man, I shop like a woman!” The effects of gender and emotions on consumer shopping behaviour outcomes. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2014, 42, 780–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teller, C.; Thomson, J.A. Gender differences of shoppers in the marketing and management of retail agglomerations. Serv. Ind. J. 2012, 32, 961–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).